Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health among a Sample of University Workers in the United Arab Emirates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Variables and Measures

2.3. The Scales Used to Assess the Mental Health Status

- (I)

- The Patient Health 9-Item Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

- (II)

- The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Questionnaire (GAD-7)

- (III)

- Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval and Consent

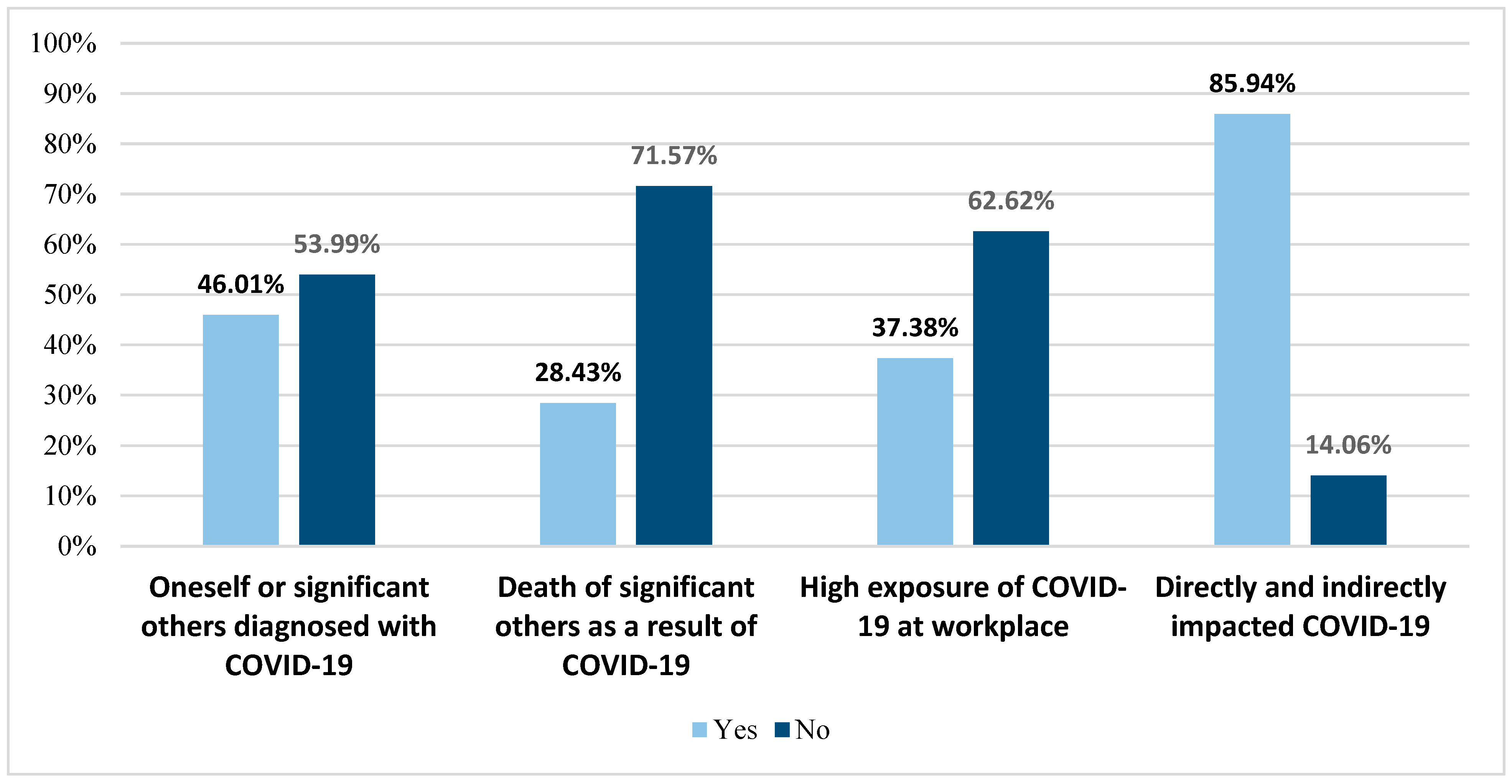

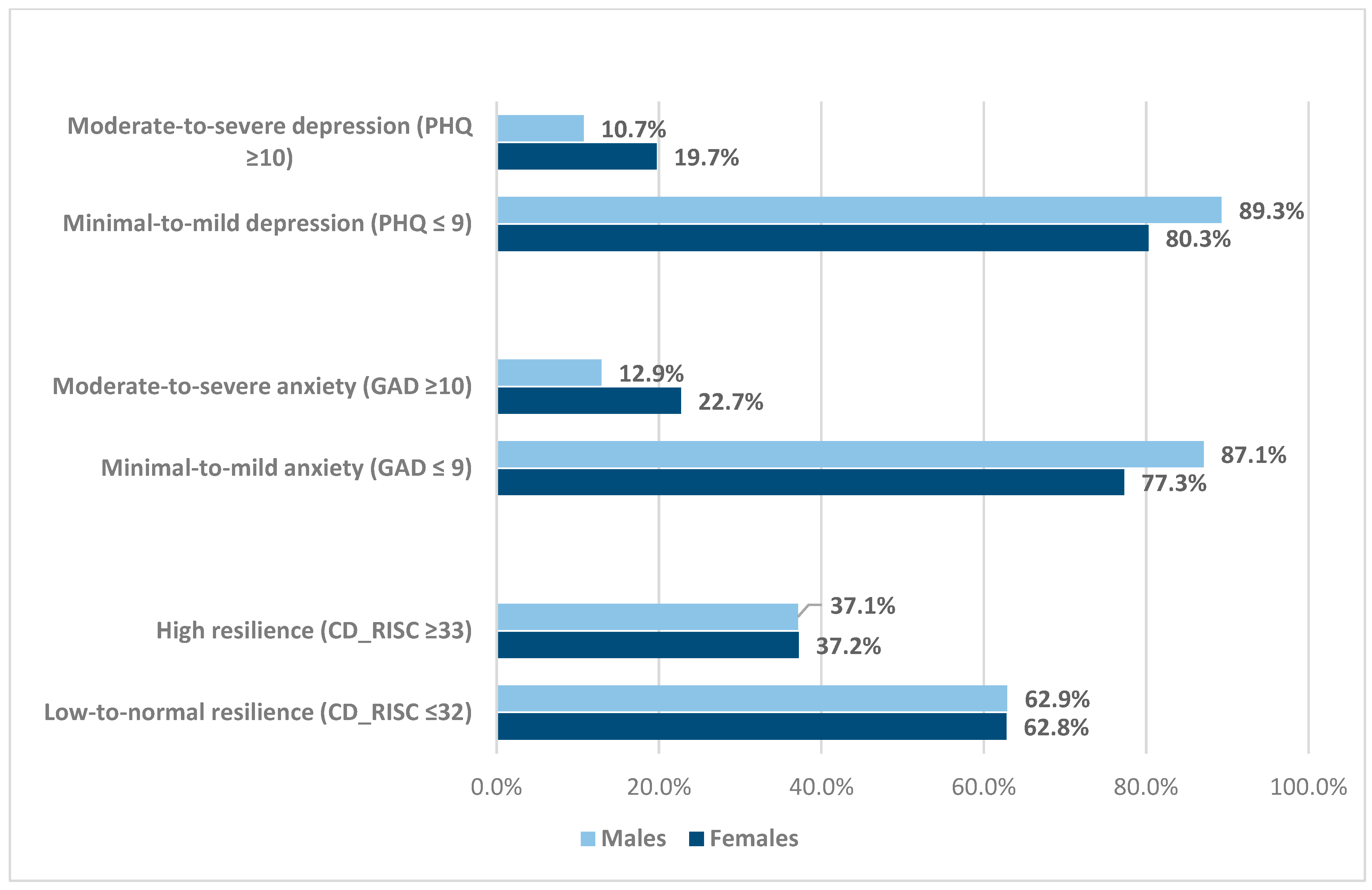

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms and the Impact of COVID-19

4.2. Socio-Demographic Differences and the Participants’ Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

4.3. Levels of Resilience and the Impact of COVID-19

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saddik, B.; Hussein, A.; Albanna, A.; Elbarazi, I.; Al-Shujairi, A.; Temsah, M.H.; Sharif-Askari, F.S.; Stip, E.; Hamid, Q.; Halwani, R. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Adults and Children in the United Arab Emirates: A Nationwide Cross-sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, K.; Peak, A.S.; Dreihaus, A. Depression, anxiety, and stress among students, faculty, and staff. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpuz, J.C.G. Workplace mental health in schools. Workplace Health Saf. 2023, 71, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Nabi, G.; Zuo, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, D. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Potential Solutions in Different Members in an Ordinary Family Unit. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 735653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhamees, A.A.; Alrashed, S.A.; Alzunaydi, A.A.; Almohimeed, A.S.; Aljohani, M.S. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the general population of Saudi Arabia. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, K.A.; Iqbal, N.; Mushtaq, A. Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: Examining the indirect and moderating effects of worry. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017, 29, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouche, S. COVID-19 and Employees’ Mental Health: Stressors, Moderators and Agenda for Organizational Actions. Emerald Open Res. 2023, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotney, A. Why Mental Health Needs to Be a Top Priority in the Workplace. 2022. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/apa/2022/surgeon-general-workplace-well-being (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Greenwood, K.; Anas, J. It’s a New Era for Mental Health at Work. Harvard Business Review. 2021. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/10/its-a-new-era-for-mental-health-at-work (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Scarpis, E.; Del Pin, M.; Ruscio, E.; Tullio, A.; Brusaferro, S.; Brunelli, L. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression within the University community: The cross-sectional UN-SAD study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallhi, T.H.; Khan, N.A.; Siddique, A.; Salman, M.; Bukhari, S.N.A.; Butt, M.H.; Khan, F.U.; Khalid, M.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Tanveer, N.; et al. Mental Health and Coping Strategies among University Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross–Sectional Analysis from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallhi, T.H.; Ahmad, N.; Salman, M.; Tanveer, N.; Shah, S.; Butt, M.H.; Alatawi, A.D.; Alotaibi, N.H.; Rahman, H.U.; Alzarea, A.I. Estimation of Psychological Impairment and Coping Strategies during COVID-19 Pandemic among University Students in Saudi Arabia: A Large Regional Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kita, Y.; Yasuda, S.; Gherghel, C. Online education and the mental health of faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Santxo, N.B.; Mondragon, N.I.; Santamaría, M.D. The psychological state of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis: The challenge of returning to face-to-face teaching. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 620718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BTI 2022 United Arab Emirates Country Report. BTI 2022. 2022. Available online: https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/ARE (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Policy in Action Series: The Heart of Competitiveness: The Higher Education Creating the Future of the UAE. Available online: https://fcsc.gov.ae/en-us/Lists/D_Reports/Attachments/31/Issue%206%20-%20Higher%20Education.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Quality Education. The Official Portal of the UAE Government. UAE in 2021. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/leaving-no-one-behind/4qualityeducation (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Patwary, M.M.; Disha, A.S.; Bardhan, M.; Haque, M.Z.; Kabir, M.P.; Billah, S.M.; Hossain, R.; Alam, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Shuvo, F.K.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward coronavirus and associated anxiety symptoms among university students: A cross-sectional study during the early stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 856202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Scherer, N.; Felix, L.; Kuper, H. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlHadi, A.N.; Alarabi, M.A.; AlMansoor, K.M. Mental health and its association with coping strategies and intolerance of uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic among the general population in Saudi Arabia: Cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Miskry, A.S.; Hamid, A.A.; Darweesh, A.H. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on university faculty, staff, and students and coping strategies used during the lockdown in the United Arab Emirates. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 682757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higher Colleges of Technology Handbook 2020 and 2021. Available online: https://myhctportal.hct.ac.ae/Pages/staffpublications.aspx (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample Size Calculator by Raosoft, Inc. 2022. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Schwenk, T.; Terrell, L.; Harrison, R.; Tremper, A.; Valenstein, M.; Bostwick, J. Ambulatory Unipolar Depression Guidelines. University of Michigan Health Clinical Care Guidelines. Update 2021. Available online: https://michmed-public.policystat.com/policy/8093108/latest/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Umegaki, Y.; Todo, N. Psychometric properties of the Japanese CES–D, SDS, and PHQ–9 depression scales in university students. Psychol. Assess 2017, 29, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassiani-Miranda, C.A.; Vargas-Hernández, M.C.; Pérez-Anibal, E.; Herazo-Bustos, M.I.; Hernández-Carrillo, M. Reliability and dimensionality of PHQ-9 in screening depression symptoms among health science students in Cartagena, 2014. Biomedica 2017, 37, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Med. Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CD-RISC: About. 2023. Available online: https://www.connordavidson-resiliencescale.com/about.php (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Velickovic, K.; Rahm Hallberg, I.; Axelsson, U.; Borrebaeck, C.A.K.; Rydén, L.; Johnsson, P.; Månsson, J. Psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in a non-clinical population in Sweden. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, S.; Moore, E.; Newton, M.; Galli, N. Validity and reliability of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in competitive sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 23, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewski, K.P.; Piegza, M.; Gospodarczyk, A.Z.; Gospodarczyk, N.J.; Sosada, K. Impact of Selected Sociodemographic and Clinical Parameters on Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Paramedics in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Blooshi, M.; Al Ameri, T.; Al Marri, M.; Ahmad, A.; Leinberger-Jabari, A.; Abdulle, A. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on depression and anxiety symptoms: Findings from the United Arab Emirates Healthy Future (UAEHFS) cohort study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayle, N. Half of UK University Staff Showing Signs of Depression, Report Shows. 2021. Available online: https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/11839/Half-of-UK-University-staff-showing-signs-of-depression-report-shows (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Rakhmanov, O.; Demir, A.; Dane, S. A brief communication: Anxiety and depression levels in the staff of a Nigerian private university during COVID 19 pandemic outbreak. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2020, 8, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Razzak, H.A.; Harbi, A.; Ahli, S. Depression: Prevalence and associated risk factors in the United Arab Emirates. Oman Med. J. 2019, 34, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, K.; Huak Chan, Y.; Chong, P.N.; Chua, H.C.; Wen, S.S. Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e924609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkire, N.; Mrklas, K.; Hrabok, M.; Gusnowski, A.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Abba-Aji, A. COVID-19 pandemic: Demographic predictors of self-isolation or self-quarantine and impact of isolation and quarantine on perceived stress, anxiety, and depression. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 553468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, R.; Ismail, M.E. The psychological distress and COVID-19 pandemic during lockdown: A cross-sectional study from United Arab Emirates (UAE). Heliyon 2022, 8, e09422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajpeyi Misra, A.; Mamdouh, H.M.; Dani, A.; Mitchell, V.; Hussain, H.Y.; Ibrahim, G.M.; Alnakhi, W.K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of university students in the United Arab Emirates: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Otaibi, B.; Al-Weqayyan, A.; Taher, H.; Sarkhou, E.; Gloom, A.; Aseeri, F. Depressive symptoms among Kuwaiti population attending primary healthcare setting: Prevalence and influence of sociodemographic factors. Med. Princ. Pract. 2007, 16, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinkers, C.H.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Branchi, I.; Cryan, J.F.; Domschke, K.; Howes, O.D.; Manchia, M.; Pinto, L.; de Quervain, D.; et al. Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 35, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000, 109, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Blasi, M.; Albano, G.; Bassi, G.; Mancinelli, E.; Giordano, C.; Mazzeschi, C. Factors related to women’s psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a two-wave longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, D.D.; Song, J.; Lyons, J.S.; Manheim, L.M.; Chang, R.W. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, D.L.; Puterman, E.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Matthews, K.A.; Adler, N.E. Race, life course socioeconomic position, racial discrimination, depressive symptoms and self-rated health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorant, V.; Deliège, D.; Eaton, W.; Robert, A.; Philippot, P.; Ansseau, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.K.; Mokonogho, J.; Kumar, A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galenkamp, H.; Stronks, K.; Snijder, M.B.; Derks, E.M. Measurement invariance testing of the PHQ-9 in a multi-ethnic population in Europe: The HELIUS study. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, R.; Dandona, R.; Gururaj, G.; Dhaliwal, R.S.; Singh, A.; Ferrari, A.; Dua, T.; Ganguli, A.; Varghese, M.; Chakma, J.K.; et al. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, M.A.; Pinto, N.S. Experiential COVID-19 factors predicting resilience among Spanish adults. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturman, E.D. Coping with COVID-19: Resilience and psychological well-being in the midst of a pandemic. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 39, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, S.; Marciano, H.; Eshel, Y.; Adini, B. Recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic: Distress and resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, Q.G.; Vandelanotte, C.; Cope, K.; Khalesi, S.; Williams, S.L.; Alley, S.J.; Thwaite, T.L.; Fenning, A.S.; Stanton, R. The association of resilience with depression, anxiety, stress and physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidelines for Office and Workplace Environment during Emergency Conditions—The Official Portal of the UAE Government. UAE. 2021. Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/justice-safety-and-the-law/handling-the-covid-19-outbreak/guidelines-related-to-covid-19/guidelines-for-office-and-workplace-environment-during-emergency-conditions (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Abbas Zaher, W.; Ahamed, F.; Ganesan, S.; Warren, K.; Koshy, A. COVID-19 crisis management: Lessons from the United Arab Emirates leaders. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 724494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wu, W.H.; Doolan, G.; Choudhury, N.; Mehta, P.; Khatun, A.; Hennelly, L. Marital status and gender differences as key determinants of COVID-19 impact on wellbeing, job satisfaction and resilience in health care workers and staff working in academia in the UK during the first wave of the pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 928107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Males | 138 (44.5) |

| Females | 172 (55.5) | |

| Marital status | Single/Never Married | 56 (17.9) |

| Ever Married | 257 (82.1) | |

| Current age (in years) | 20 to 33 | 49 (15.6) |

| 34 to 49 | 153 (48.9) | |

| 50+ | 111 (35.5) | |

| Nationality | UAE Nationals | 55 (17.6) |

| Non-UAE Nationals | 258 (82.4) | |

| Employment Status | Faculty and Teaching Staff | 225 (71.9) |

| Non-Teaching (Administrative) staff | 88 (28.1) | |

| Residence (by Emirate) | Abu Dhabi and Western Region | 68 (21.7) |

| Dubai | 122 (39.0) | |

| North Emirates | 123 (39.3) | |

| Total | 313 (100.0) | |

| Psychometric Property | Impacted by COVID-19 N (%) | Not Impacted by COVID-19 N (%) | Total Sample N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression as measured by the PHQ-9 | |||

| Minimal-to-mild depression (score ≤ 9) | 222 (82.5) | 42 (95.5) | 264 (84.3) |

| Moderate-to-severe depression (score ≥ 10) | 47 (17.5) | 2 (4.5) | 49 (15.7) * |

| Anxiety as measured by the GAD-7 | |||

| Minimal-to-mild anxiety (score ≤ 9) | 218 (81.1) | 37 (84.1) | 255 (81.5) |

| Moderate-to-severe anxiety (Score ≥ 10) | 51 (18.9) | 7 (15.9) | 58 (15.5) |

| Resilience as measured by the CD-RISC-10 | |||

| Low-to-normal resilience (≤32) | 172 (63.9) | 24 (54.5) | 196 (62.7) |

| High resilience (score ≥ 33) | 97 (36.1) | 97 (36.1) | 117 (37.3) |

| Total | 269 (100) | 44 (100) | 313 (100) |

| Scale | Impacted by COVID-19 | Not-Impacted by COVID-19 | T Value | * p Value | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Scores (±SD) | |||||

| PHQ-9 | 5.37 (5.30) | 3.05 (3.94) | −2.78 | 0.008 * | 5.04 (5.19) |

| GAD-7 | 5.26 (5.59) | 4.30 (5.48) | −1.06 | >0.05 | 5.13 (5.58) |

| CD-RISC-10 | 29.58 (7.10) | 29.07 (9.80) | −0.41 | >0.05 | 29.51 (7.53) |

| Scale | Mean Scores (±SD) | T Value | * p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Male | Female | ||

| PHQ-9 | 4.10 (4.89) | 5.81 (5.31) | −2.921 | 0.004 |

| GAD-7 | 4.14 (5.29) | 5.94 (5.69) | −2.866 | 0.004 |

| CD-RISC-10 | 29.47 (6.93) | 29.53 (8.00) | −0.074 | 0.941 |

| UAE national | Non-national | |||

| PHQ-9 | 6.37 (5.49) | 4.77 (5.10) | 2.066 | 0.040 |

| GAD-7 | 7.39 (6.03) | 4.65 (5.38) | 3.320 | 0.001 |

| CD-RISC-10 | 25.92 (8.62) | 30.28 (7.07) | −3.945 | 0.000 |

| Teaching | Non-Teaching | |||

| PHQ-9 | 5.17 (5.29) | 4.70 (4.93) | 0.519 | 0.474 |

| GAD-7 | 5.16 (5.61) | 5.05 (5.53) | 0.940 | 0.870 |

| CD-RISC-10 | 29.52 (7.82) | 29.46 (6.76) | 0.563 | 0.953 |

| Ever married | Single/never married | |||

| PHQ-9 | 4.98 (5.29) | 5.32 (4.72) | 0.445 | 0.657 |

| GAD-7 | 4.83 (5.45) | 6.50 (5.97) | 2.040 | 0.032 |

| CD-RISC-10 | 30.01 (7.05) | 27.20 (9.14) | −2.557 | 0.011 |

| Scale | Impacted by COVID-19 | Not Impacted by COVID-19 | * p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Score (±SD) | |||

| PHQ-9 | |||

| Male | 4.38 (5.11) | 2.80 (3.65) | 0.015 |

| Female | 6.09 (5.36) | 3.50 (4.46) | |

| GAD-7 | |||

| Male | 4.19 (5.39) | 3.96 (5.10) | 0.123 |

| Female | 6.07 (5.66) | 4.94 (6.16) | |

| CD-RISC-10 | |||

| Male | 29.18 (6.43) | 30.60 (9.11) | 0.226 |

| Female | 29.84 (7.61) | 26.89 (10.83) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Misra, A.V.; Mamdouh, H.M.; Dani, A.; Mitchell, V.; Hussain, H.Y.; Ibrahim, G.M.; Kotb, R.; Alnakhi, W.K. Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health among a Sample of University Workers in the United Arab Emirates. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111153

Misra AV, Mamdouh HM, Dani A, Mitchell V, Hussain HY, Ibrahim GM, Kotb R, Alnakhi WK. Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health among a Sample of University Workers in the United Arab Emirates. Healthcare. 2024; 12(11):1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111153

Chicago/Turabian StyleMisra, Anamika V., Heba M. Mamdouh, Anita Dani, Vivienne Mitchell, Hamid Y. Hussain, Gamal M. Ibrahim, Reham Kotb, and Wafa K. Alnakhi. 2024. "Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health among a Sample of University Workers in the United Arab Emirates" Healthcare 12, no. 11: 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111153

APA StyleMisra, A. V., Mamdouh, H. M., Dani, A., Mitchell, V., Hussain, H. Y., Ibrahim, G. M., Kotb, R., & Alnakhi, W. K. (2024). Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health among a Sample of University Workers in the United Arab Emirates. Healthcare, 12(11), 1153. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111153