Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices about Hyperuricemia and Gout in Community Health Workers and Patients with Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Development

2.2. Population and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Community Health Workers

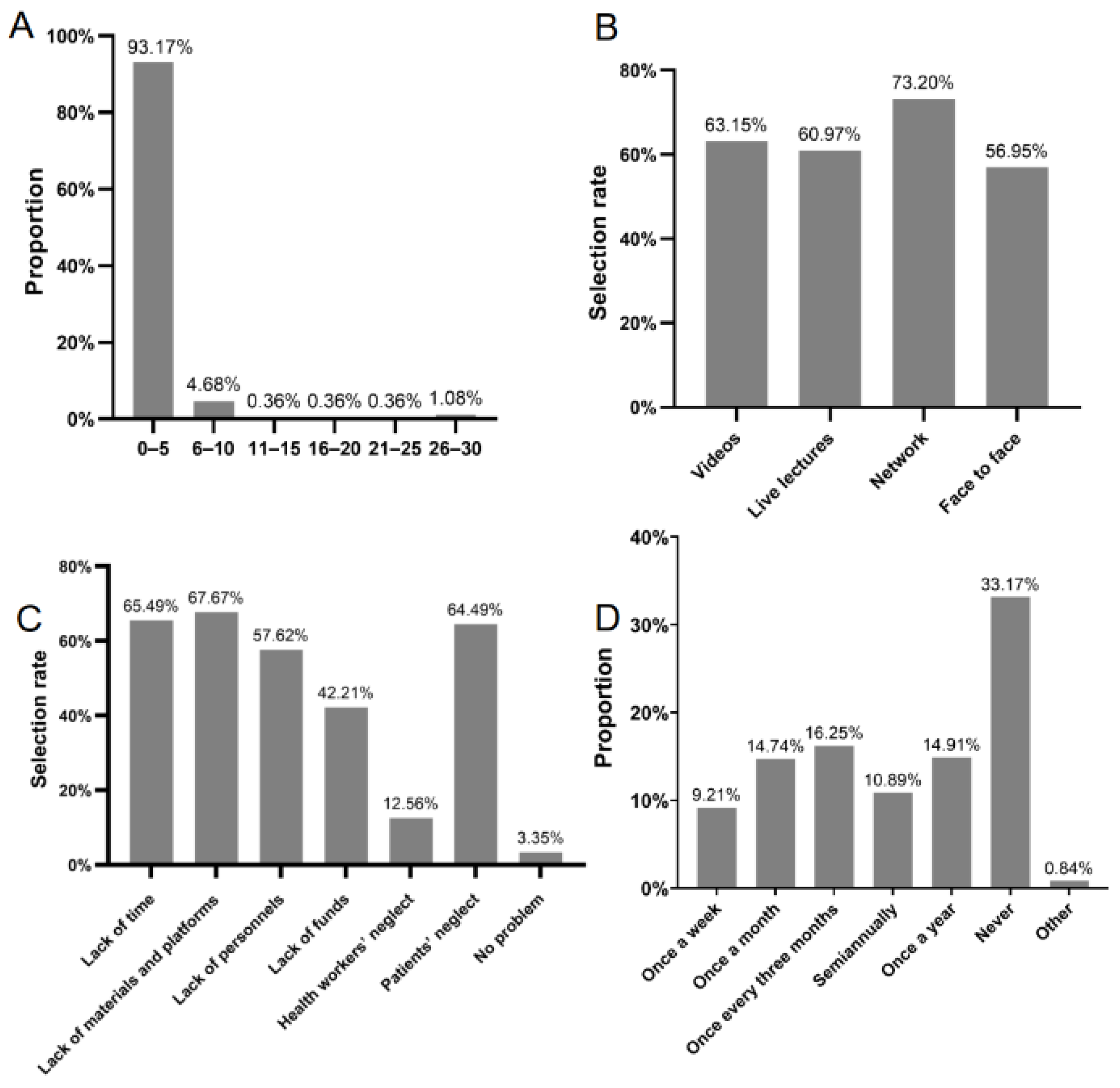

3.2. Practices and Attitudes of Community Health Workers for Patient Education

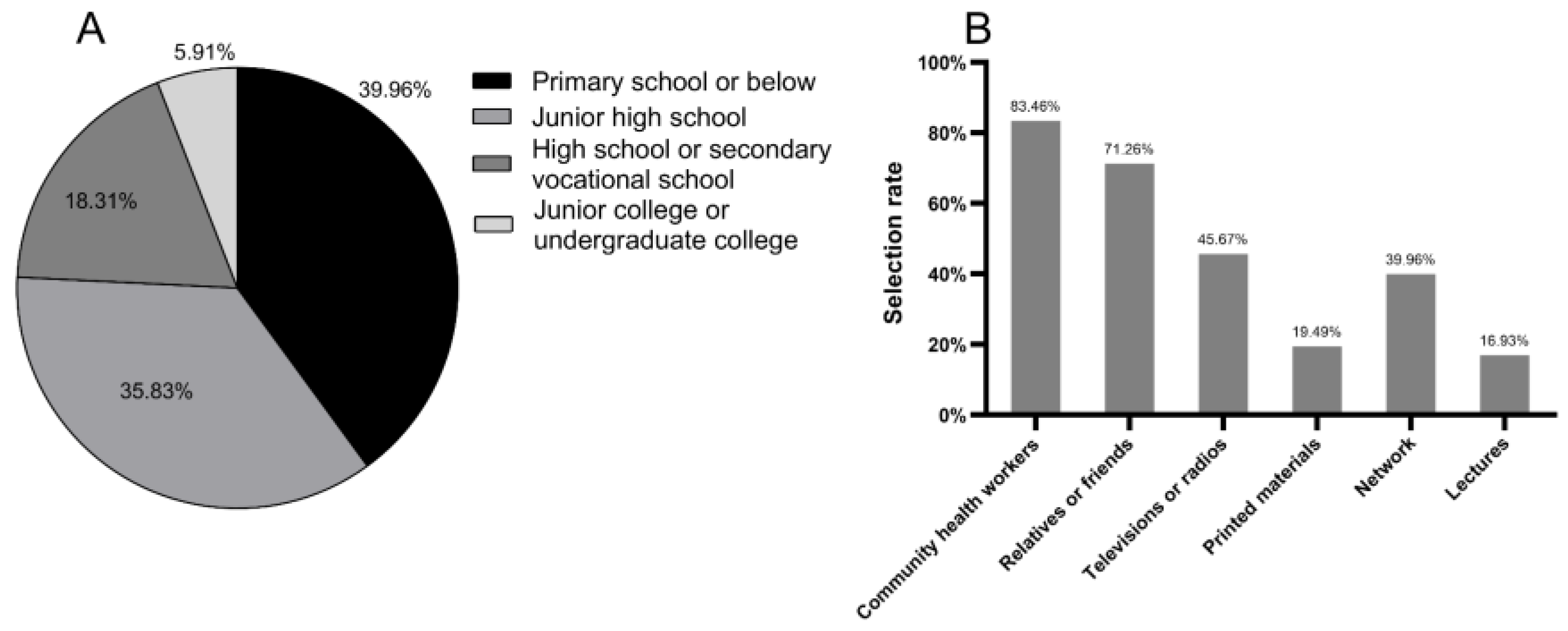

3.3. Characteristics of Patients with Diabetes

3.4. Practices and Attitudes of Patients with Diabetes for Education

3.5. Knowledge of Hyperuricemia and Gout among Community Health Workers

3.6. Knowledge of Hyperuricemia and Gout among Patients with Diabetes

3.7. Factors Influencing Knowledge Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gliozzi, M.; Malara, N.; Muscoli, S.; Mollace, V. The treatment of hyperuricemia. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 213, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benn, C.L.; Dua, P.; Gurrell, R.; Loudon, P.; Pike, A.; Storer, R.I.; Vangjeli, C. Physiology of hyperuricemia and urate-lowering treatments. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbeth, N.; Gosling, A.L.; Gaffo, A.; Abhishek, A. Gout. Lancet 2021, 397, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Wu, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y.; Wan, W.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia among Chinese adults: Findings from two nationally representative cross-sectional surveys in 2015-16 and 2018-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 791983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Mu, Y.; Zou, D.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X. Two-year changes in hyperuricemia and risk of diabetes: A five-year prospective cohort study. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 6905720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, R.P.; Lei, L.; Song, Q.Q.; Zhang, R.Y.; Li, Y.B.; Yang, C.; Lin, S.D.; Chen, L.S.; Wang, Y.L.; et al. Prevalence and determinants of hyperuricemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with central obesity in Guangdong Province in China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 22, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Han, C.; Wu, D.; Xia, X.; Gu, J.; Guan, H.; Shan, Z.; Teng, W. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout in mainland China from 2000 to 2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 762820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.M.; Chen, C.J.; Su, B.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Yu, S.F.; Yen, J.H.; Hsieh, M.C.; Cheng, T.T.; Chang, S.J. Gout and type 2 diabetes have a mutual inter-dependent effect on genetic risk factors and higher incidences. Rheumatology 2012, 51, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhana, A.; Lee, G.; Dalbeth, N. Factors influencing the crystallization of monosodium urate: A systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danve, A.; Sehra, S.T.; Neogi, T. Role of diet in hyperuricemia and gout. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 35, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaruban, A.; Soden, M.; Larkins, S. General practitioners’ perspectives on the management of gout: A qualitative study. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 92, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, R.; Nguyen, A.; Graham, G.; Aung, E.; Coleshill, M.; Stocker, S. Better outcomes for patients with gout. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, T.R.; Batterman, A. How can we improve disease education in people with gout? Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuzic Furlan, S.; Rusic, D.; Bozic, J.; Rumboldt, M.; Rumboldt, Z.; Rada, M.; Tomicic, M. How are we managing patients with hyperuricemia and gout: A cross sectional study assessing knowledge and attitudes of primary care physicians? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqarni, N.A.; Hassan, A.H. Knowledge and practice in the management of asymptomatic hyperuricemia among primary health care physicians in Jeddah, Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostka-Jeziorny, K.; Widecka, K.; Tykarski, A. Study of epidemiological aspects of hyperuricemia in Poland. Cardiol. J. 2019, 26, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nie, F.Q.; Huang, X.B.; Tang, W.; Hu, R.; Zhang, W.Q.; Liu, J.X.; Xu, R.H.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D.; et al. High prevalence and low awareness of hyperuricemia in hypertensive patients among adults aged 50-79 years in southwest China. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrold, L.R.; Mazor, K.M.; Peterson, D.; Naz, N.; Firneno, C.; Yood, R.A. Patients’ knowledge and beliefs concerning gout and its treatment: A population based study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, K.; Carr, A.; Doherty, M. Patient and provider barriers to effective management of gout in general practice: A qualitative study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, F.L. Poorly controlled gout: Who is doing poorly? Singap. Med. J. 2016, 57, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokose, C.; McCormick, N.; Choi, H.K. Dietary and lifestyle-centered approach in gout care and prevention. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakutani-Hatayama, M.; Kadoya, M.; Okazaki, H.; Kurajoh, M.; Shoji, T.; Koyama, H.; Tsutsumi, Z.; Moriwaki, Y.; Namba, M.; Yamamoto, T. Nonpharmacological management of gout and hyperuricemia: Hints for better lifestyle. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 11, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Cao, F.; Ran, X.A.-O. Prevalence and associated factors of hyperuricemia among Chinese patients with diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X. Guideline for primary care of gout and hyperuricemia:practice version (2019). Chin. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 19, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of hyperuricemia and gout in China (2019). Chin. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Spaetgens, B.; Pustjens, T.; Scheepers, L.; Janssens, H.; van der Linden, S.; Boonen, A. Knowledge, illness perceptions and stated clinical practice behaviour in management of gout: A mixed methods study in general practice. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 35, 2053–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, M.; Pullman-Mooar, S.; Hussain, F.; Schumacher, H.R. Evaluating appropriate use of prophylactic colchicine for gout flare prevention. Arthritis Care Res. 2014, 66, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Schumacher, H.R.; Su, H.H.; Lie, D.; Dinnella, J.; Baker, J.F.; Von Feldt, J.M. Development and evaluation of a survey of gout patients concerning their knowledge about gout. J. Clin. Rheumatol. Pract. Rep. Rheum. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2011, 17, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.H.; Dai, L.; Li, Z.X.; Liu, H.J.; Zou, C.J.; Ou-Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Li, T.; Li, Y.H.; Mo, Y.Q.; et al. Questionnaire survey evaluating disease-related knowledge for 149 primary gout patients and 184 doctors in South China. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 32, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, N.; Bryant, L.; Te Karu, L.; Aho, L.; Chan, R.; Miao, J.; Naidoo, C.; Singh, H.; Tieu, A. Living with gout in New Zealand: An exploratory study into people’s knowledge about the disease and its treatment. J. Clin. Rheumatol. Pract. Rep. Rheum. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2012, 18, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbeth, N.; Petrie, K.J.; House, M.; Chong, J.; Leung, W.; Chegudi, R.; Horne, A.; Gamble, G.; McQueen, F.M.; Taylor, W.J. Illness perceptions in patients with gout and the relationship with progression of musculoskeletal disability. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 709) | GPs (n = 278) | Nurses (n = 319) | Others (n = 112) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.93 ± 7.42 | 36.97 ± 8.10 | 31.55 ± 5.89 | 33.19 ± 6.92 | <0.001 * |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 96/613 | 63/215 | 9/310 | 24/88 | <0.001 * |

| Educational Levels | |||||

| Secondary vocational school education | 20 (2.82%) | 7 (2.52%) | 7 (2.19%) | 6 (5.36%) | <0.001 * |

| Junior college degree | 248 (34.98%) | 55 (19.78%) | 158 (49.53%) | 35 (31.25%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 424 (59.80%) | 201 (72.30%) | 154 (48.28%) | 69 (61.61%) | |

| Master’s degree | 17 (2.40%) | 15 (5.40%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (1.79%) | |

| Variable | Numbers | Knowledge Scores | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 709 | 17.74 ± 3.48 | - |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 96 | 17.53 ± 3.32 | 0.953 |

| Female | 613 | 17.78 ± 3.51 | |

| Age (Years) | |||

| <30 | 194 | 16.68 ± 3.10 | <0.001 * |

| 30–39 | 387 | 18.06 ± 3.66 | |

| 40–49 | 101 | 18.50 ± 3.21 | |

| ≥50 | 27 | 18.04 ± 2.84 | |

| Educational Levels | |||

| Secondary vocational school education | 20 | 16.25 ± 2.07 | <0.001 * |

| Junior college degree | 248 | 16.98 ± 3.25 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 424 | 18.17 ± 3.52 | |

| Master’s degree | 17 | 19.94 ± 4.31 | |

| Occupations | |||

| GPs | 278 | 19.89 ± 3.26 | <0.001 * |

| Nurses | 319 | 16.24 ± 2.71 | |

| Others | 112 | 16.71 ± 3.24 | |

| Variable | Numbers | Know about Hyperuricemia or Gout n (%) | p-Value | Knowledge Scores | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 508 | 313 (61.61%) | - | 7.21 ± 7.64 | - |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 243 | 174 (71.60%) | <0.001 * | 8.23 ± 7.59 | <0.001 * |

| Female | 265 | 139 (52.45%) | 6.28 ± 7.57 | ||

| Age (Years) | |||||

| <50 | 23 | 20 (86.96%) | <0.001 * | 11.96 ± 7.57 | <0.001 * |

| 50–69 | 297 | 201 (67.68%) | 7.75 ± 7.62 | ||

| ≥70 | 188 | 92 (48.94%) | 5.78 ± 7.36 | ||

| Educational Levels | |||||

| Primary school or below | 203 | 81 (39.90%) | <0.001 * | 4.29 ± 6.67 | <0.001 * |

| Junior high school | 182 | 131 (71.98%) | 8.56 ± 7.40 | ||

| High school or secondary vocational school | 93 | 74 (79.57%) | 8.97 ± 7.71 | ||

| Junior college or undergraduate college | 30 | 27 (90.00%) | 13.33 ± 7.70 | ||

| History of Hyperuricemia or Gout | |||||

| Yes | 165 | 122 (73.94%) | <0.001 * | 10.17 ± 8.20 | <0.001 * |

| No | 343 | 191 (55.69%) | 5.79 ± 6.92 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ran, X. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices about Hyperuricemia and Gout in Community Health Workers and Patients with Diabetes. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111072

Sun S, Chen L, Chen D, Li Y, Ma L, Hou Y, Liu Y, Ran X. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices about Hyperuricemia and Gout in Community Health Workers and Patients with Diabetes. Healthcare. 2024; 12(11):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111072

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Shiyi, Lihong Chen, Dawei Chen, Yan Li, Lin Ma, Yumin Hou, Yuhong Liu, and Xingwu Ran. 2024. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices about Hyperuricemia and Gout in Community Health Workers and Patients with Diabetes" Healthcare 12, no. 11: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111072

APA StyleSun, S., Chen, L., Chen, D., Li, Y., Ma, L., Hou, Y., Liu, Y., & Ran, X. (2024). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices about Hyperuricemia and Gout in Community Health Workers and Patients with Diabetes. Healthcare, 12(11), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111072