Two-and-a-Half-Year Follow-Up Study with Freedom on Water through Stand-Up Paddling: Exploring Experiences in Blue Spaces and Their Long-Term Impact on Mental Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Freedom on Water

1.2. Definition of Mental Health

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design

2.3. Preunderstanding

2.4. Entering the Field

2.5. Ethics

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Thematic Analysis of the Empirical Data

2.8. Analytical Perspectives

3. Results

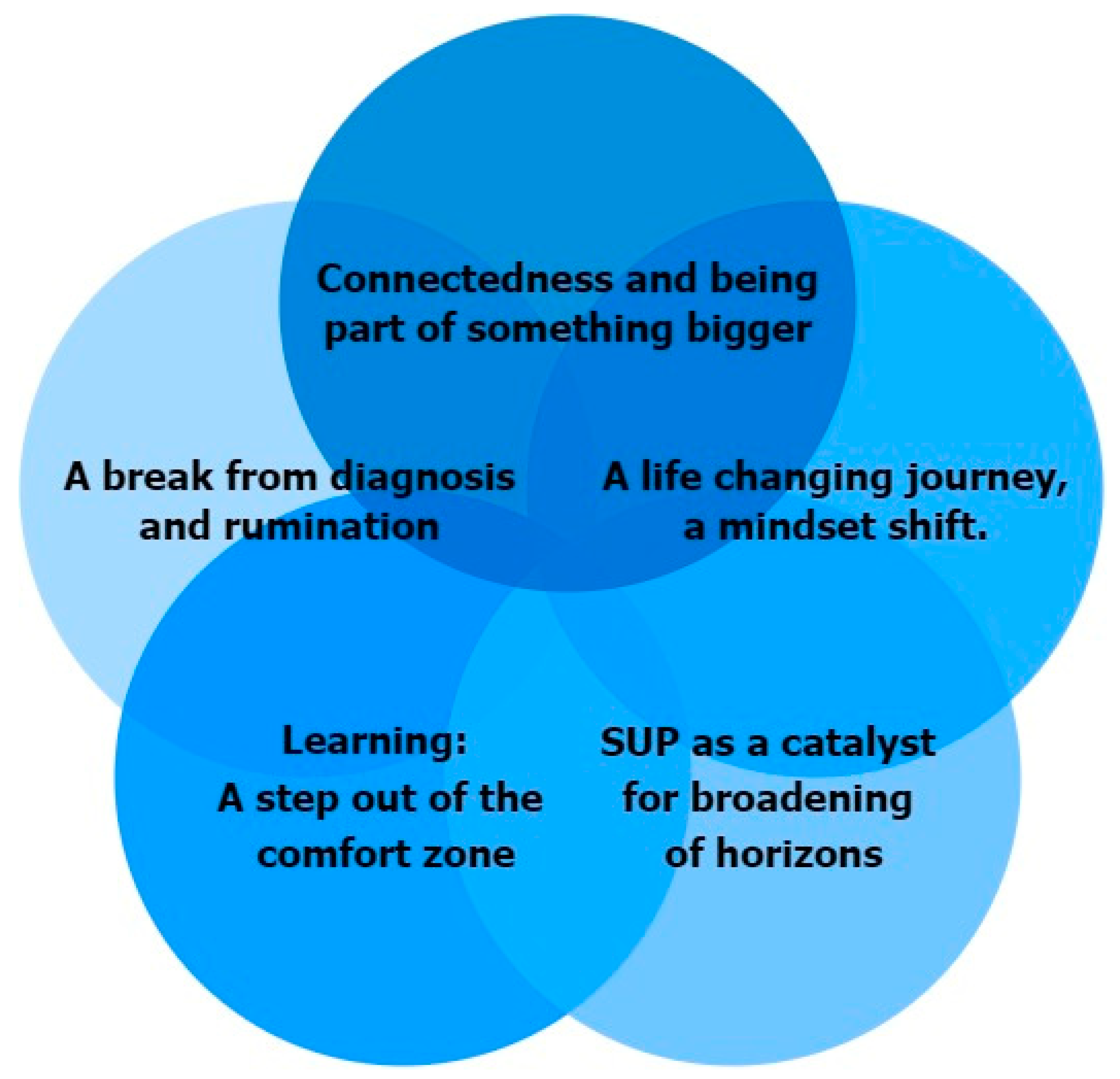

3.1. Themes

3.1.1. Theme 1: SUP as a Catalyst for the Broadening of Horizons

3.1.2. Theme 2: Learning: A Step out of the Comfort Zone

3.1.3. Theme 3: A Break from Diagnosis and Rumination

3.1.4. Theme 4: Connectedness and Being Part of Something Bigger

Theme 4a: Connectedness to Nature, Specifically Blue Nature

Theme 4b: Connectedness to the Group of Peers

3.1.5. Theme 5: A Life Changing Journey; a Mindset Shift

4. Discussion

4.1. Theme 1: SUP as a Catalyst for the Broadening of Horizons

4.2. Theme 2: Learning: Stepping out of the Comfort Zone

4.3. Theme 3: A Break from Diagnosis and Rumination

4.4. Theme 4: Connectedness and Being Part of Something Bigger

4.4.1. Theme 4a: Connectedness to Nature, Specifically Blue Nature

4.4.2. Theme 4b: Connectedness to the Group of Peers

4.5. Theme 5: A Life Changing Journey; a Mindset Shift

4.6. Limitations and Strengths

4.6.1. The Importance of This Study

4.6.2. Methods

4.6.3. Increased Awareness Verbalized Tacit Knowledge

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Interview Guide for Participants (Primary Participants)

- -

- Presentation

- -

- Setting of the interview

- -

- Guidelines, declaration of consent, and anonymization

- -

- Possible questions

- -

- How long have you been participating/or did you participate in Freedom on Water?

- -

- Why have you chosen to continue to participate?/How is your relationship with SUP since you are no longer participating in Freedom on Water?

- -

- If you think back to the first time you participated in Freedom on Water until now, how would you describe that journey?

- -

- What experiences including water/SUP did you have before you started participating in Freedom on Water?

- -

- What experiences do you have now with water/SUP besides Freedom on Water? Or after you have stopped participating?

- -

- What does SUP/water mean to you?

- -

- How has this meaning possibly changed from the first time you were on the water until now?

- -

- How have these experiences or possible changes affected you?

- -

- How would you describe your relationship towards nature/water? If there has been a change in this since Freedom on Water started, can you describe how it has changed?

- -

- How would you describe your motivation to get on the water? Do you think you would get on the water on your own if it was not through Freedom on Water?

- -

- The participant’s own additions

- -

- Thank you

Appendix A.2. Interview Guide for Instructors (Secondary Participants)

- -

- Presentation

- -

- Setting of the interview

- -

- Guidelines, declaration of consent, and anonymization

- -

- Possible questions

- -

- For how long have you been an instructor with Freedom on Water?

- -

- If you think back to the first session you held as an instructor with Freedom on Water until now, how would you describe that journey? What possibly changes have you experienced?

- -

- How do you experience having the participants with you on the water?

- -

- Why do you think that the participants have chosen to continue with SUP/Freedom on Water?

- -

- How have you experienced/observed the impact that Freedom on Water has had on the participants in the moment on the water vs. in the long run?

- -

- What do you think is necessary for the participants to achieve changes?

- -

- How have you experienced the well-being of the participants (from the beginning until now)?

- -

- What changes have you experienced/observed among the participants (from the beginning until now)?

- -

- How do you consider the participants’ retention/motivation to continue SUP (also, if Freedom on Water was to end)?

- -

- The participant’s own additions

- -

- Thank you

References

- Lindberg, M. Surf og SUP Sporten Rammer Stor Milepæl. Surf SUP Danmark. 2022. Available online: https://old.surfsup.dk/surf-sup-sporten-rammer-stor-milepael/ (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Britton, E.; Kindermann, G.; Domegan, C.; Carlin, C. Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benninger, E.; Curtis, C.; Sarkisian, G.V.; Rogers, C.M.; Bender, K.; Comero, M. Surf Therapy: A Scoping Review of the Qualitative and Quantitative Research Evidence. Glob. J. Community Psychol. Pract. 2020, 11, 1–12. Available online: https://www.gjcpp.org/pdfs/BenningerEtAl-Final.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Caddick, N.; Smith, B.; Phoenix, C. The Effects of Surfing and the Natural Environment on the Well-Being of Combat Veterans. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, C.; Devine-Wright, H.; Taylor, J. The positive impact of structured surfing courses on the wellbeing of vulnerable young people. Community Pract. 2015, 88, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sparre, P.W.; Østergaard, E.B. Freedom on Water through Stand-Up Paddling: A qualitative study on physical bodily experiences and their influence on mental health. Scand. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 5, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; WHO World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; 48p, Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO European Framework for Action on Mental Health 2021–2025; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; 36p, Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289057813 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. Bedre Mental Sundhed og en Styrket Indsats til Mennesker med Psykiske Lidelser. Sundhedsstyrelsen. 2022. Available online: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2022/psykiatriplan/10AARS_PSYK-PLAN.ashx?la=da&hash=CD317811318C4499D2453F25DCEC92B9DF41DE08 (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Surf & Sup Danmark. n.d. Surf & Sup Danmark. Available online: https://surfsup.dk/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Surf & Sup Danmark. Fri på Vandet. Available online: https://surfsup.dk/fri-pa-vandet (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- The Danish Outdoor Council. Friluftsrådet—The Danish Outdoor Council. About the Danish Outdoor Council. Available online: https://friluftsraadet.dk/about-the-danish-outdoor-council (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health; WHO World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T.; Reventlow, S. Kvalitative metoder. In Forebyggende Sundhedsarbejde; Bruun Jensen, B., Grønbæk, M., Reventlow, S., Eds.; Munksgaard: København, Denmark, 2021; pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, J.P. Participant Observation; Wadsworth Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 1980; 195p. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.S.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, D.B. Fænomenologi. Filosofi, metode og analytisk værktøj. In Forskningsmetoder i Folkesundhedsvidenskab; Jensen, A.M.B., Vallgårda, S., Eds.; Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- AU Studypedia Centre for Educational Development. AU Studypedia. 2023. Opgavens Opbygning. Available online: https://studypedia.au.dk/skriv-opgaven/opgavens-opbygning (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Bundgaard, H.; Overgaard Mogensen, H. Analyse: Arbejdet med det etnografiske materiale. In Antropologiske Projekter: En Grundbog. 1. Udgave; Bundgaard, H., Overgaard Mogensen, H., Rubow, C., Eds.; Samfundslitteratur: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2018; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Høyer, K. Hvad er teori, og hvordan forholder teori sig til metode? In Forskningsmetoder i Folkesundhedsvidenskab. 4. Udgave; Vallgårda, S., Koch, L., Eds.; Munksgaard: København, Denmark, 2011; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott, H.F. The Art of Fieldwork; Altamira: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2001; 285s. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Kvalitative Forskningsmetoder for Medisin og Helsefag; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects; World Medical Association: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013; Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 26 April 2018).

- Hardon, A.; Boonmongkon, P.; Streefland, P.; Tan, M. Applied Health Research Manual: Anthropology of Health and Health Care; Spinhuis: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.K.; Maryniuk, M.D. Building Therapeutic Relationships: Choosing Words That Put People First. Clin. Diabetes 2017, 35, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Østergaard, E.B. Kategoriserende betegnelser i forbindelse med kronisk sygdom. Fag Og Forsk. 2008, 2008, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, K. People First Language. Disabilityisnatural. 2006. Available online: https://nebula.wsimg.com/3afd3cde772330d273fedd163fec9c85?AccessKeyId=9D6F6082FE5EE52C3DC6&disposition=0&alloworigin=1 (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- World Physiotherapy. World Physiotherapy Congress 2025. Call for Focused Symposia: Submission Guidelines. 2024. Available online: https://wp2025.world.physio/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/WP2025-call-for-FS-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. Tilblivelseshistorier: Barnløshed, Slægtskab og Forplantningsteknologi i Danmark. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut for Antropologi, Københavns Universitet, København, Denmark, 1998. vi, 283 sider p. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interview: Det Kvalitative Forskningsinterview Som Håndværk; Hans Reitzel: København, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall Series in Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; 617p. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. (Eds.) Handbook of Self-Determination Research; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; 470p. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: Optimaloplevelsens Psykologi; Dansk psykologisk Forlag: Virum, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kirketerp, A. Craft-psykologi—Sundhedsfremmende effekter ved håndarbejde og håndværk. Unge Pædagog 2020, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnoli, M.A.; Lee, T.D. Challenge Point: A Framework for Conceptualizing the Effects of Various Practice Conditions in Motor Learning. J. Mot. Behav. 2004, 36, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Kroppens Fænomenologi; Det lille Forlag: Helsingør, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xww&AN=282598&site=ehost-live (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; 493p. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. World-Centred Education: A View for the Present; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Capurso, M.; Borsci, S. Effects of a tall ship sail training experience on adolescents’ self-concept. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 58, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grocott, A.C.; Hunter, J.A. Increases in global and domain specific self-esteem following a 10 day developmental voyage. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2009, 12, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhurst, J.; Hunter, J.A.; Kafka, S.; Boyes, M. Enhancing resilience in youth through a 10-day developmental voyage. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2013, 15, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, K.; McLaughlin, P.; Allison, P.; Edwards, V.; Tett, L. Sail training as education: More than mere adventure. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2010, 36, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S.; Wabano, M.J.; Russell, K.; Enosse, L.; Young, N. Promoting resilience and wellbeing through an outdoor intervention designed for Aboriginal adolescents. Rural Remote. Health 2014, 14, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, L.; Fisher, Z.; Kemp, A.H. The ‘Rippling’ Waves of Wellbeing: A Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Surf-Therapy Intervention on Patients with Acquired Brain Injury. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingsworth, M.A.; Gilbert, D.T. A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind. Science 2010, 330, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Shortt, N.; Rind, E.; Mitchell, R. Life Course, Green Space and Health: Incorporating Place into Life Course Epidemiology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, T.P.; Tyrväinen, L.; Korpela, K.M. The Relationship between Perceived Health and Physical Activity Indoors, Outdoors in Built Environments, and Outdoors in Nature. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 6, 324–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Butler, C.W. Nature connectedness and biophilic design. Build. Res. Inf. 2022, 50, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S. Brinkmanns Briks: Kan Strikketøj Gøre Dig Lykkelig? Available online: https://www.dr.dk/lyd/p1/brinkmanns-briks/brinkmanns-briks-2023/brinkmanns-briks-kan-strikketoej-goere-dig-lykkelig-11032321393 (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Kirketerp, A. Craft-Psykologi: Sundhedsfremmende Effekter ved Håndarbejde og Håndværk. 1. Udgave; Mailand: Hjørring, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, J. Kroppens filosofi: Med baggrund i Maurice Merleau-Pontys forfatterskab. Kognit Pædagog. 2002, 12, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, E.B.; Nielsen, B.W.; Wiegaard, L.; Jørgensen, M.M.; Madsen, H.N.; Dahlgaard, J.O. Den glemte krop: Når berøring og bevægelse virker positivt på sindet til fremme for mental sundhed. Sundhedsprofessionelle Stud. 2022, 6, 1–24. Available online: https://tidsskrift.dk/Sundhedsprofessionnelle_studier/issue/archive (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Djernis, D.; Lundsgaard, C.M.; Rønn-Smidt, H.; Dahlgaard, J. Nature-Based Mindfulness: A Qualitative Study of the Experience of Support for Self-Regulation. Healthcare 2023, 11, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R.; Barbiero, G.; Barbiero, P.; Senes, G. An Individual’s Connection to Nature Can Affect Perceived Restorativeness of Natural Environments. Some Observations about Biophilia. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidenius, U.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Poulsen, D.V.; Bondas, T. “I look at my own forest and fields in a different way”: The lived experience of nature-based therapy in a therapy garden when suffering from stress-related illness. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1324700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lencastre, M.P.A.; Vidal, D.G.; Estrada, R.; Barros, N.; Maia, R.L.; Farinha-Marques, P. The biophilia hypothesis explored: Regenerative urban green spaces and well-being in a Portuguese sample. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaekwad, J.S.; Moslehian, A.S.; Roös, P.B.; Walker, A. A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Evidence for the Biophilia Hypothesis and Implications for Biophilic Design. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 750245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keniger, L.E.; Gaston, K.J.; Irvine, K.N.; Fuller, R.A. What are the Benefits of Interacting with Nature? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Dobson, J.; Abson, D.J.; Lumber, R.; Hunt, A.; Young, R.; Moorhouse, B. Applying the pathways to nature connectedness at a societal scale: A leverage points perspective. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.R. The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public Health Nutr. 1999, 2, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penedo, F.J.; Dahn, J.R. Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2005, 18, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson Coon, J.; Boddy, K.; Stein, K.; Whear, R.; Barton, J.; Depledge, M.H. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Carol Dweck Revisits the “Growth Mindset”. Educ. Week. 2015. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-carol-dweck-revisits-the-growth-mindset/2015/09 (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Adloff, F.; Gerund, K.; Kaldewey, D. (Eds.) Revealing Tacit Knowledge: Embodiment and Explication; Presence and Tacit Knowledge; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2015; 308p. [Google Scholar]

| Theme: Nature and Water | Empirical Data |

|---|---|

| Nature and water | “I specifically strive to see some water, like if it is possible to go for a walk along the water then I just feel really good. Then I can imagine myself being out there where nobody can reach me, and I can just be in the moment”. |

| Theme: Nature and Water | Empirical Data |

|---|---|

| Sub-group: changes in perceptions of nature | “Water didn’t really mean anything to me, it wasn’t something special, neither was nature, but now I appreciate it more. I have a desire to go out, like now I can see that nature has more opportunities, that you can go out and enjoy it in several ways”. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Østergaard, E.B.; Sparre, P.W.; Dahlgaard, J. Two-and-a-Half-Year Follow-Up Study with Freedom on Water through Stand-Up Paddling: Exploring Experiences in Blue Spaces and Their Long-Term Impact on Mental Well-Being. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12101004

Østergaard EB, Sparre PW, Dahlgaard J. Two-and-a-Half-Year Follow-Up Study with Freedom on Water through Stand-Up Paddling: Exploring Experiences in Blue Spaces and Their Long-Term Impact on Mental Well-Being. Healthcare. 2024; 12(10):1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12101004

Chicago/Turabian StyleØstergaard, Elisabeth Bomholt, Pernille Wobeser Sparre, and Jesper Dahlgaard. 2024. "Two-and-a-Half-Year Follow-Up Study with Freedom on Water through Stand-Up Paddling: Exploring Experiences in Blue Spaces and Their Long-Term Impact on Mental Well-Being" Healthcare 12, no. 10: 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12101004

APA StyleØstergaard, E. B., Sparre, P. W., & Dahlgaard, J. (2024). Two-and-a-Half-Year Follow-Up Study with Freedom on Water through Stand-Up Paddling: Exploring Experiences in Blue Spaces and Their Long-Term Impact on Mental Well-Being. Healthcare, 12(10), 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12101004