Robots for Elderly Care: Review, Multi-Criteria Optimization Model and Qualitative Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review

3. An Overview of Mobile Service Robot Applications

Robot Types on Different Robotic Platforms

- ARI [48]—is a mobile humanoid service robot whose primary design goals are to increase user acceptance of social robots and to use AI algorithms for caring.

- ASTRO [49]—assists elderly individuals with their indoor walking activities and physical training.

- Bandit [50]—is a wheeled platform with a humanoid torso. Physical exercise and cognitive training for the elderly are encouraged.

- Care-O-bot [51]—this robot can be used as a research platform as well as for a variety of tasks such as collection and delivery, independent living for the elderly, security or surveillance, and welcoming and guidance in retail stores or museums.

- Gymmy [52]—robot concentrates primarily on upper-body tasks.

- HealthBot [53]—robot can be used as a prescription or schedule reminder, a fall detector, an entertainment or memory assistant, and a phone caller. Furthermore, it monitors vital signs such as blood pressure, arterial stiffness, pulse rate, blood oxygen saturation, and blood glucose levels.

- Hobbit [54]—is a mobile platform with a depth camera for precise navigation and detection. A wireless call button, automatic voice recognition or gesture recognition interfaces, and a touchscreen allow users to engage with the robot.

- IRMA [55]—robot for locating misplaced objects that can be used to assist seniors.

- Kompaï [56]—a digital platform for social assistance. This robot promotes independent living and socialization among the elderly. The Kompaï robot performs a variety of functions, including day and night surveillance, mobility aid, fall detection, shopping list management, agenda, social connectivity, cognitive stimulation, and health monitoring. The robot can also recognize speech, navigate through unpredictable environments, avoid barriers, and detect potentially dangerous circumstances. Individuals connect with the robot using a touch screen and voice, and it has a little handle to assist the elderly in rising.

- Max [57]—a companion robot designed to provide long-term help to elderly persons at home.

- Pearl [58]—an autonomous mobile robot that responds to daily obstacles faced by the elderly, such as reminders and environmental direction. This robot can navigate autonomously, identify speech, distinguish faces, and compress photos in order to improve online video streaming with elderly relatives.

- Personal Robot 1 (PR1) [59]—this is a multifunctional human-assisting mobile manipulating robot developed to assist humans, particularly the elderly, in living independently and interacting with them.

- Personal Robot 2 (PR2) [60]—aside from a high level of engagement, like PR1, PR2 can see the environment in 3D, which aids it in autonomous navigation. Furthermore, it can walk dogs, fold clothing, open doors, and accomplish other similar chores, thanks to its flexible arms.

- RAMCIP [62]—a service robot that offers safe and proactive everyday support to the elderly, particularly those with memory difficulties. This robot platform can be used for a wide range of tasks, including emergency detection (fall detection and gas/smoke detection), assistance in keeping the home safe (turning off electric appliances such as an oven or turning on lamps for locomotion), communication with relatives and friends, medication reminders, food preparation assistance, and picking up fallen objects.

- Robovie [63]—provides various services, such as helping with social isolation problems, daily greeting, conversing, assisting the elderly with complex activities, assisting in the grocery, and showing shop locations in a mall. This robot can communicate with humans by speaking and gesticulating, acting like a human youngster, and moving its eyes or head to express significant behaviors.

- Rudy [64]—using machine learning techniques, the robot provides remote monitoring, medication reminders, fall detection/prevention, and social networking.

- SCITOS A5 [65]—with a panoramic view, it is capable of people identification and tracking, object recognition, and 3D spatiotemporal mapping, and it provides entertaining programs for all ages. The robot’s frequency component for map improvement, which aids it in coping with environmental changes, is an exciting aspect. This robot was utilized as a walking companion for physical therapy groups of older people with advanced dementia.

- SoftBank Robotics Pepper [66]—robot was created for a variety of objectives, including cognitive training, health monitoring, companionship, scheduling reminders, greeting, discussion, surveying, educational purposes, entertainment, autism therapies, and even screening staff members during the COVID-19 epidemic. Using perception modules, the robot is capable of speech and emotional detection, sound localization, safe navigation, displaying body language, and engaging with the environment.

- Stevie [67]—robot is capable of providing long-term care for seniors and those with disabilities. This mobile platform has a human-like torso and two short arms.

- TIAGo [68]—a robotics research platform with basic environmental detection, learning, navigation, and obstacle-avoidance capabilities. Several research initiatives have made use of these robot platforms. The ENRICHME [69] project is one example of employing TIAGo to create a SAR for assisting the elderly, adjusting to their needs, and behaving naturally.

4. Service Robots vs. Social Robots for Elderly Care

- Robotic Assistants: these are robots that can help with daily duties including cleaning, cooking, and medication reminders. They are outfitted with sensors and cameras to help them traverse the house and complete duties.

- Personal Robots: these robots are intended to offer elderly people companionship. They can converse, play games, and provide amusement. They are also equipped with sensors that detect falls and monitor vital signs.

- Telepresence Robots: these are robots that have video conferencing capabilities and can communicate with healthcare professionals, family members, and friends, remotely. They are also suitable for virtual tours and social gatherings.

- Robotic Exoskeletons: these are wearable robotic devices that can aid the elderly in their mobility. They provide aid and support during walking and can also be utilized for rehabilitation.

- Companion Robots: these are robots that are developed to offer senior citizens companionship. They can converse, play games, and provide amusement. They are outfitted with sensors that detect and respond to human emotions, and they can also deliver medicine and appointment reminders.

- Pet Robots: these are robots that resemble the appearance and behavior of pets. They can offer the elderly comfort and emotional support if they are unable to have a live pet owing to physical constraints or living situations.

- Cognitive Assistants: these are robots developed to assist the elderly suffering from cognitive impairments such as dementia. They can serve as reminders for daily duties, aid with memory exercises, and provide cognitive stimulation.

- Telepresence Robots: these are robots that have video conferencing capabilities and can communicate with healthcare professionals, family members, and friends, remotely. They are also suitable for virtual tours and social gatherings.

5. Optimization Model

Multi-Criteria Optimization Robot Assignment for Elderly with Robot Utilization Level and Caregiver Stress Level (M-CORAEUS)

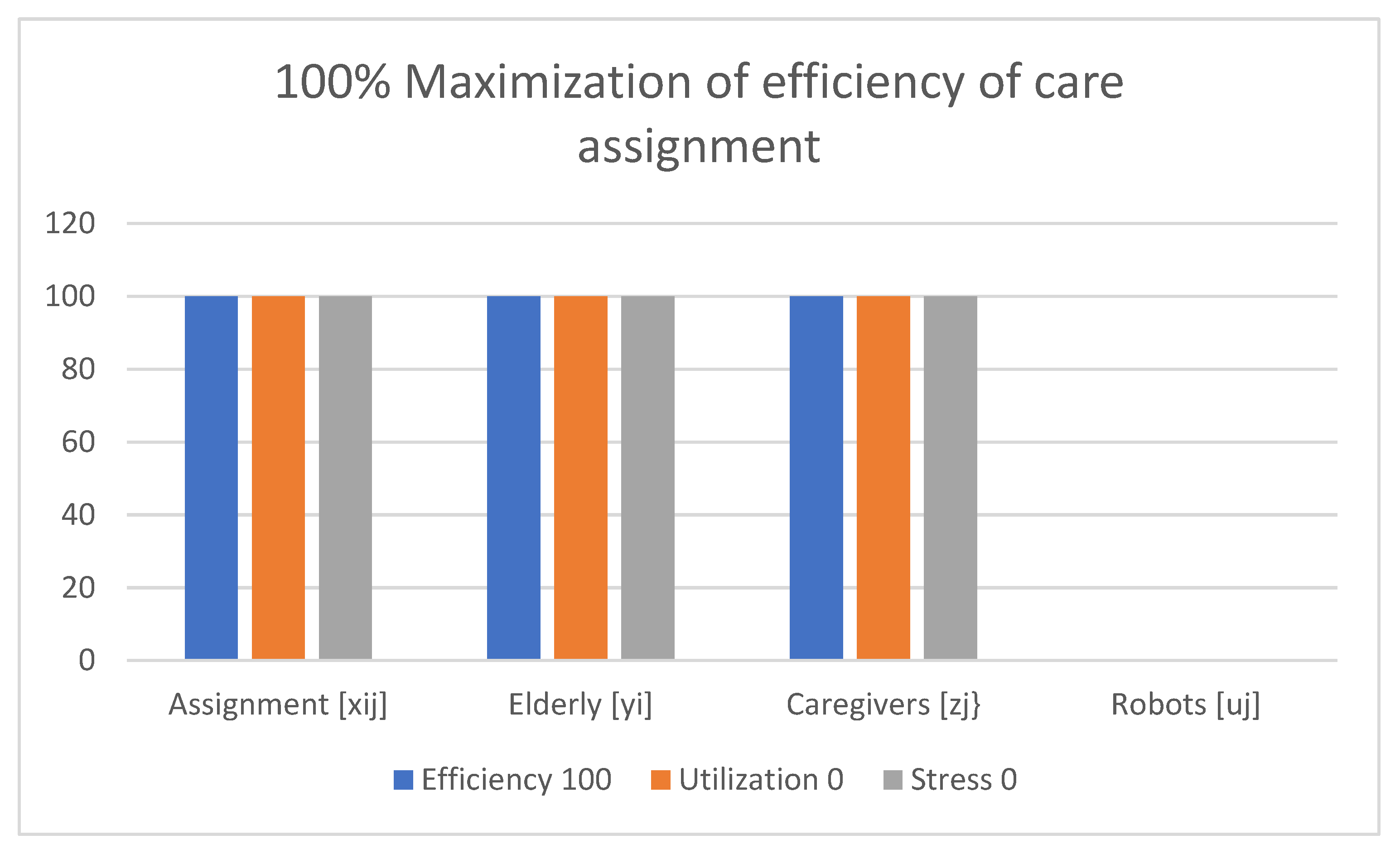

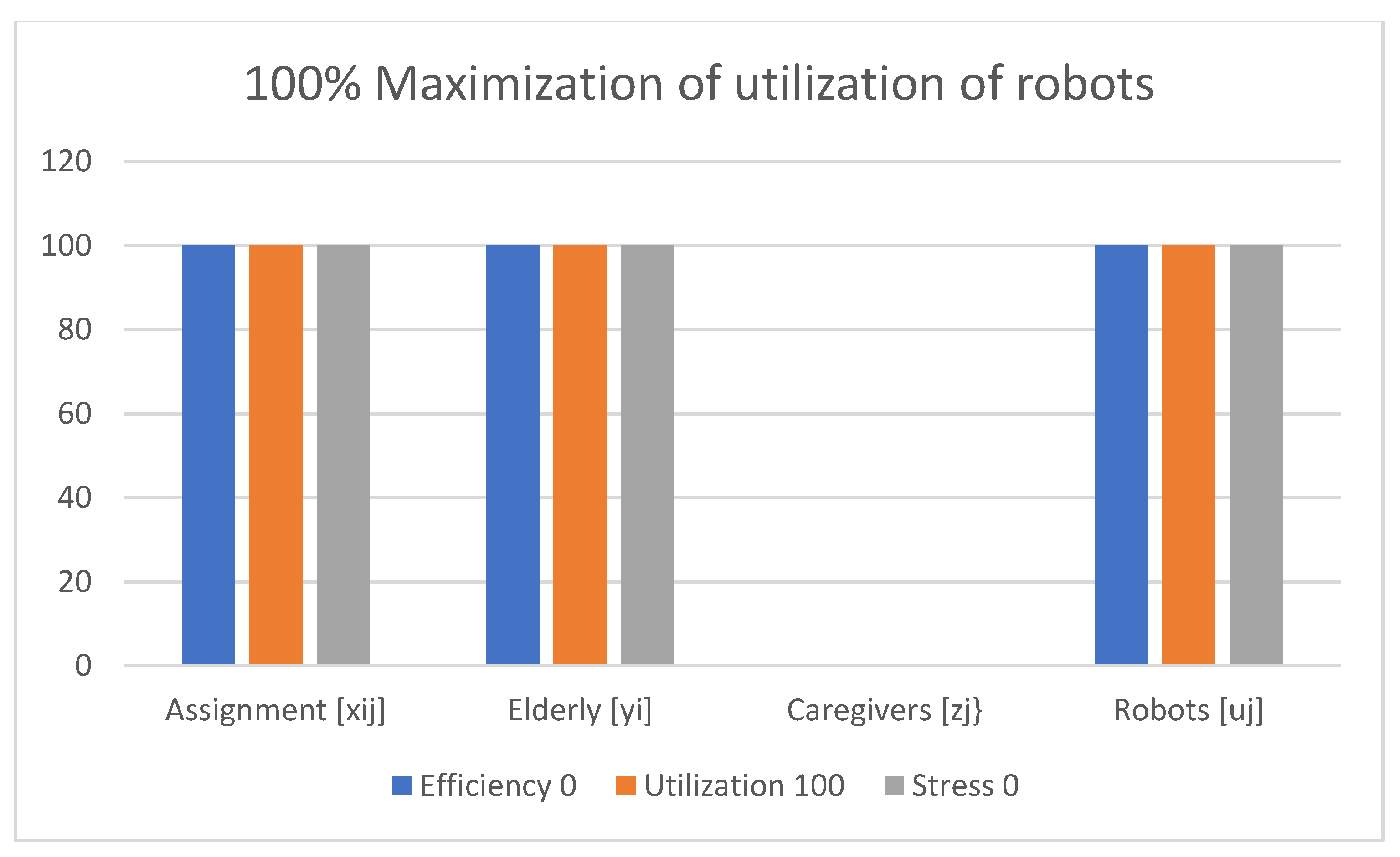

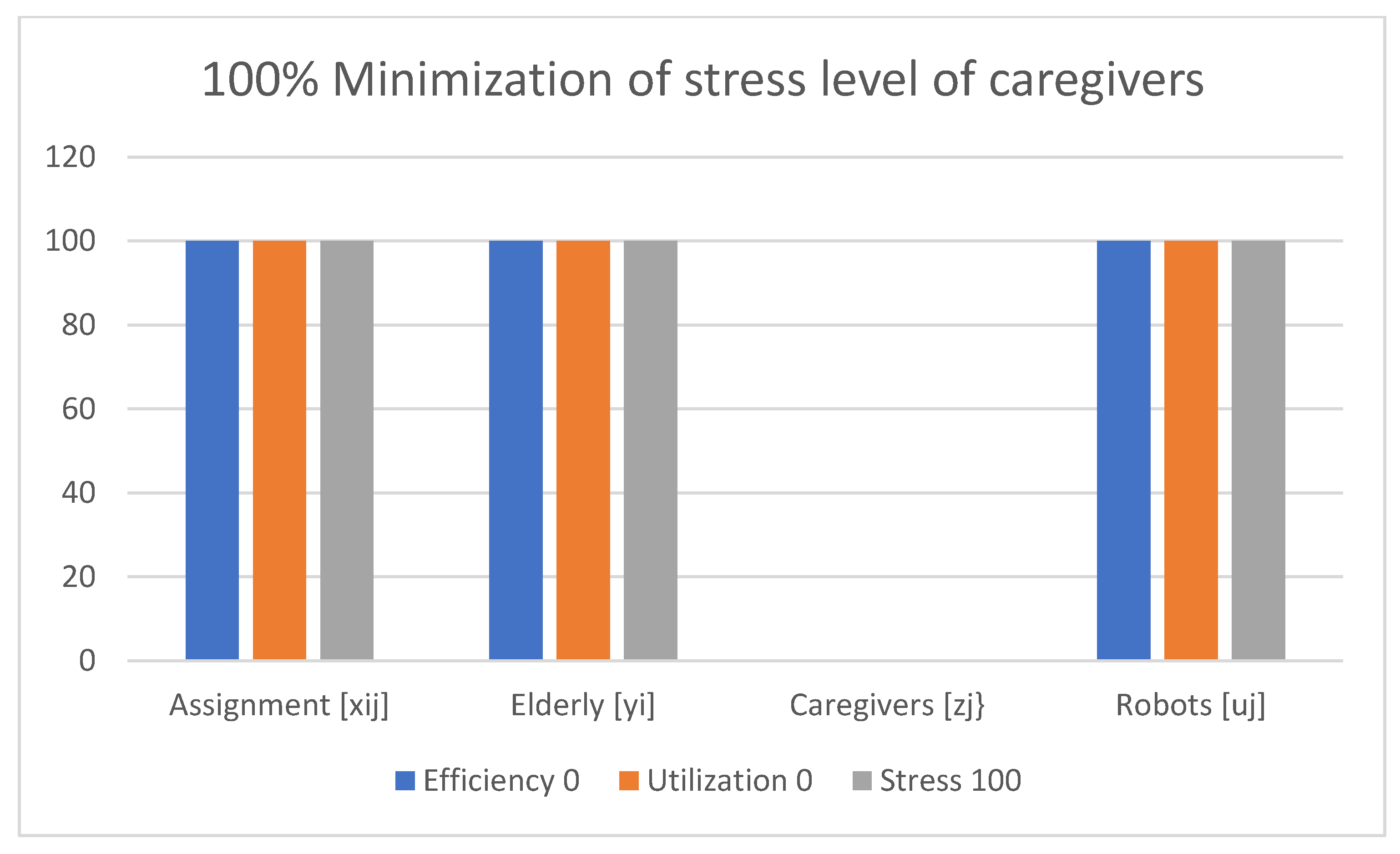

- Equation (1) describes multi-criteria (triple-objective) objective function, where efficiency of robots/caregivers’ assignment and utilization of robots service level is maximized, while caregivers’ stress level is minimized.

- Equations (2)–(4) describe the condition of the assignment considered for robots and caregivers for the elderly.

- Equation (5) describes the condition that assigns either caregiver or robot to the elderly.

- Equations (6)–(9) describe the variable ranges.

6. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

7. Results

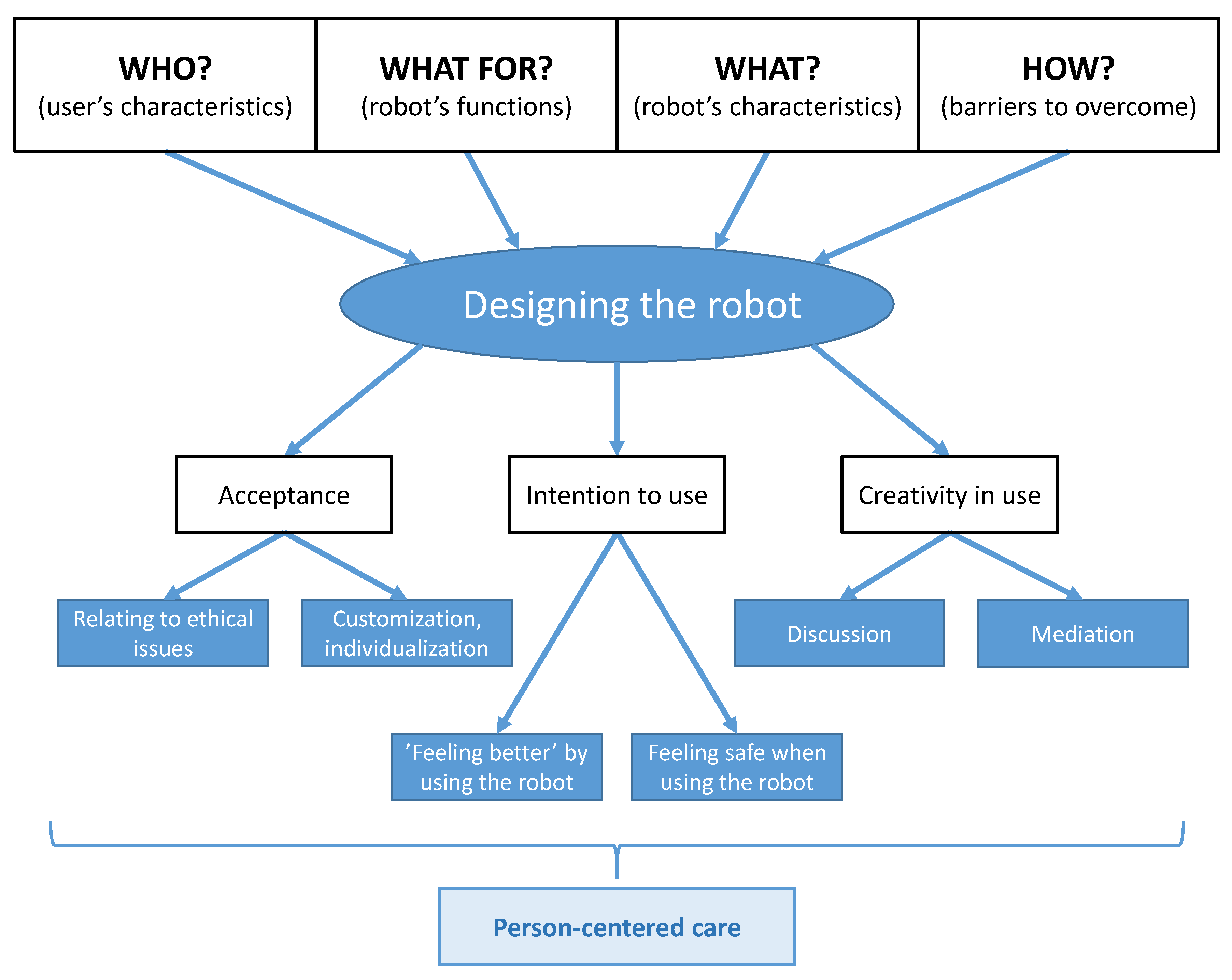

- WHO is the potential beneficiary of owning/using a robot? What distinguishes the robots’ users from other older adults?

- WHAT should the robot be like? Which features are indicated as meaningful?

- WHAT could the robot be used FOR? Which are its most important functions in terms of its usability?

- HOW should the robot be implemented into the care provision for older individuals? Which potential problems must be solved for the robot’s introduction to be effective?

- The participants on the one hand stressed that the robot is “a machine that has no emotions (...) and human (...) does not know all of the machine’s behavior; (...) I do not know if it would be nice for older people; I understand that younger ones have a different view because they are more familiar” (A). On the other hand, it was stated that the robot is “(…) a friend for all that matters, universal” (3), and “a friend because a friend always gives good advice (…)” (2).

- It should be emphasized that older participants had a lot more expectations towards the robot than the caregivers, and these expectations were more elaborated, for example:

- Conducting discussions—participants pondered if “it would be possible to talk politics? (…) But, what if the robot had different political views?” (8) “I could have an opponent. The discussion would be better then” (9).

- Safety issues—they discussed the possibility of the opening of the door by the robot and checking who comes in, with the decision not to let people come in to cheat/rob the older person. There appeared a question, “would it let a thief in?” (6) and an observation, “someone who has been let in could damage the robot.” (8)

- Mediation—the robot could (as an impartial party) participate in solving conflicts with neighbors or family, and everybody would adhere to its decisions, “There are problems with your wife or with children, and you can ask the robot to solve the problem.” (6)

- The participants agreed that “for sure, the robot will not replace a human but, (…) if someone wanted that, let them cooperate [play or work together].” (B) In this context, we found further statements, notably: “a human always looks in a different way because he has sight because he has eyes, facial expressions, and feelings,” and (F) “this is simply equipment, and a man needs another man.” (5) Thus, both the older persons and the caregivers clearly distinguished the presence of the robot from that of a human.

- It was pointed out that robots are a solution for the future. The robot “is a good thing, only that we will not wait.” (5) “I think it will work fantastic for people who are now 15 years old, as they will be 70–80; this will be the ideal solution.” (H)

- Much of the talk was devoted to ethical issues. Among other topics, it was discussed who should have control over the robot and access to the observational data, “I cannot imagine the robot would be programmed so that my son or daughter could control it and that it would follow their orders (...), I would feel incapacitated” (1). It was clear to all participants that access to data must be limited and that “not that one will come and see, only the one person authorized to do so;” (1) for example, if it was a daughter, “the mother would have to agree to the daughter’s right for insight.” (1) To the formal caregivers, it was apparent that, while the monitored health parameters could be transmitted, observing the older user (image transmission) is “entering with shoes in [violating] someone’s privacy.” (I). The potential users expressed the wish not to be spied on by the robot. Hence, the robot’s functions must be considered and implemented in an individualized way, to avoid the sense of “being controlled” from the perception of the older robot’s user.

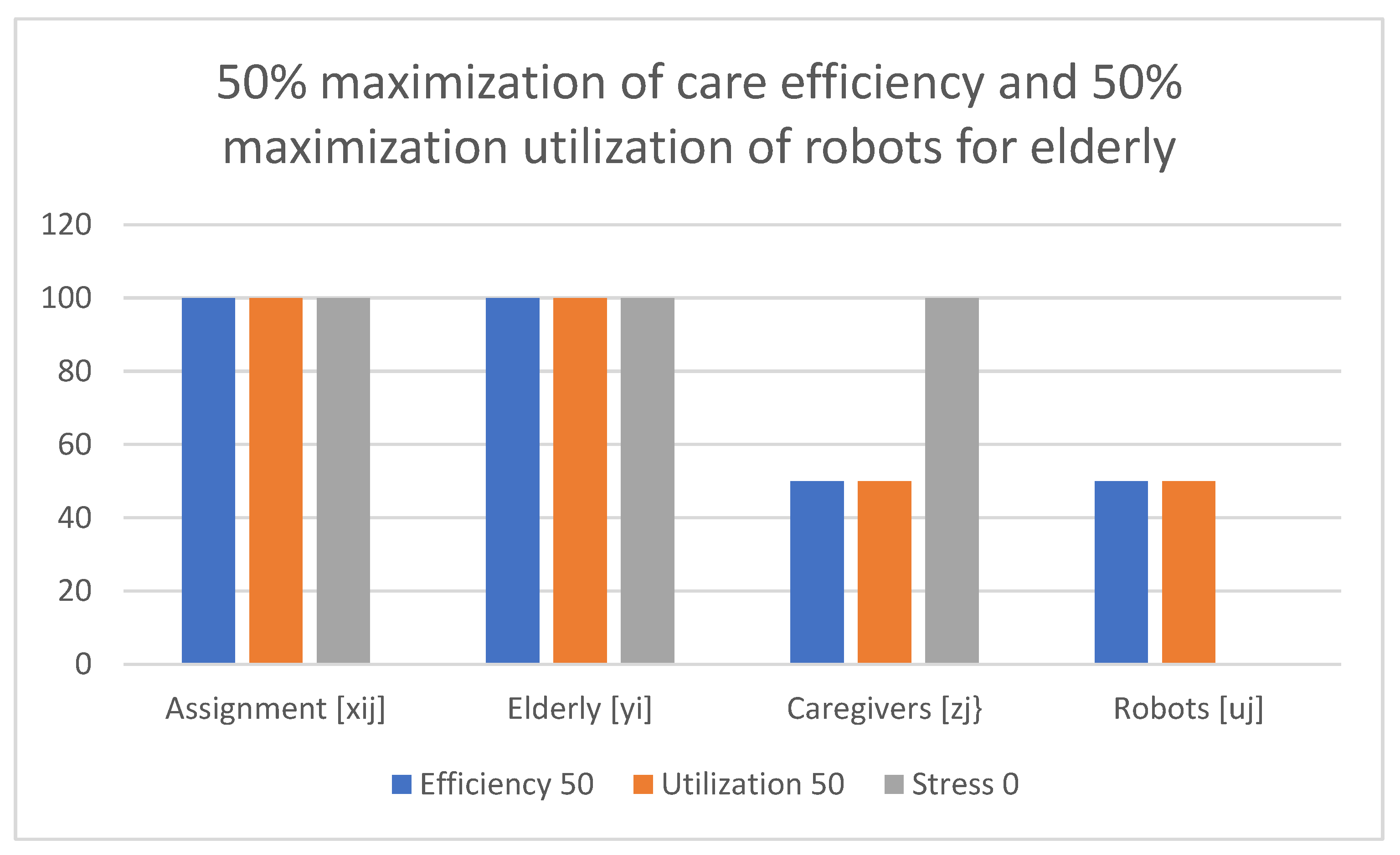

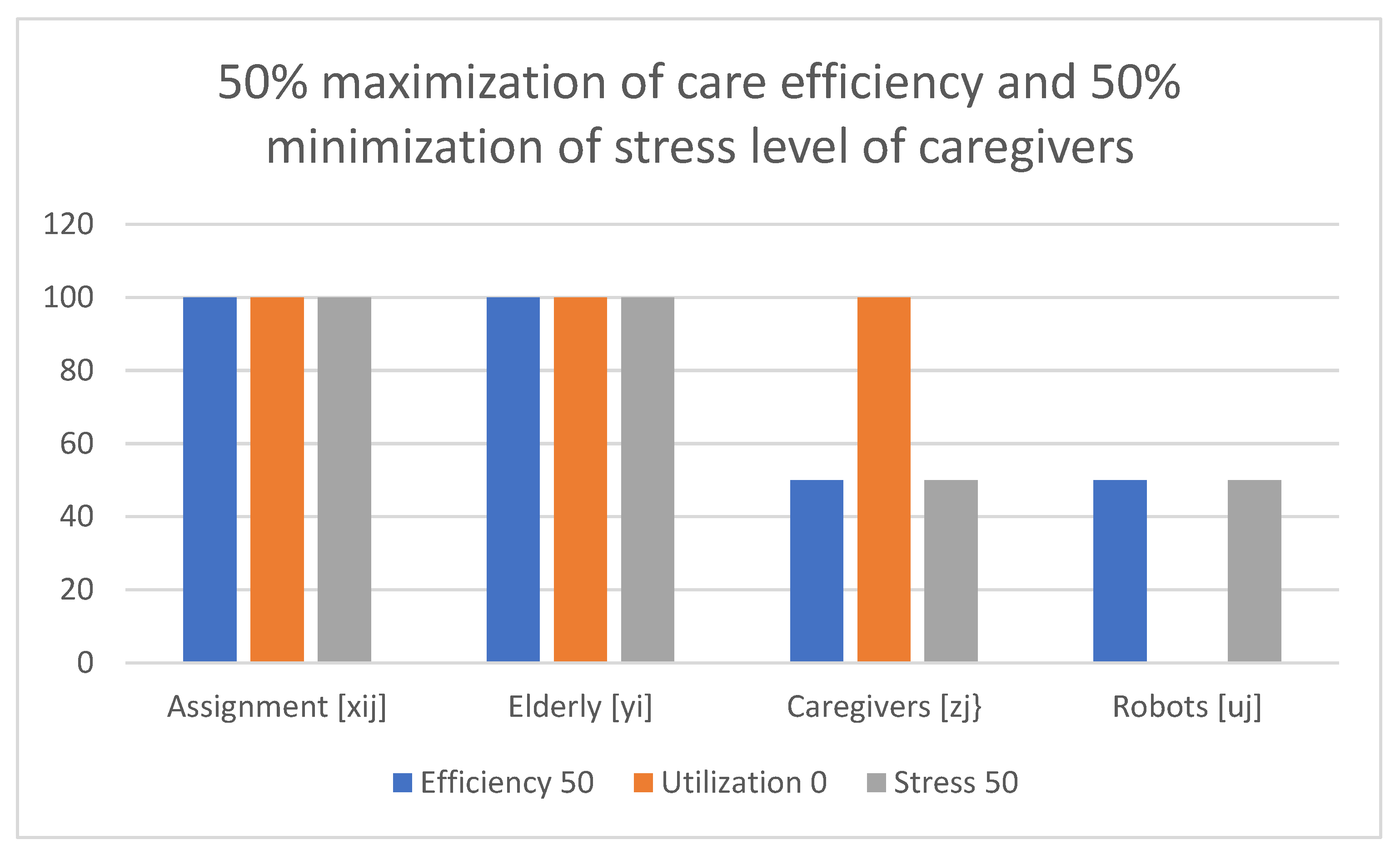

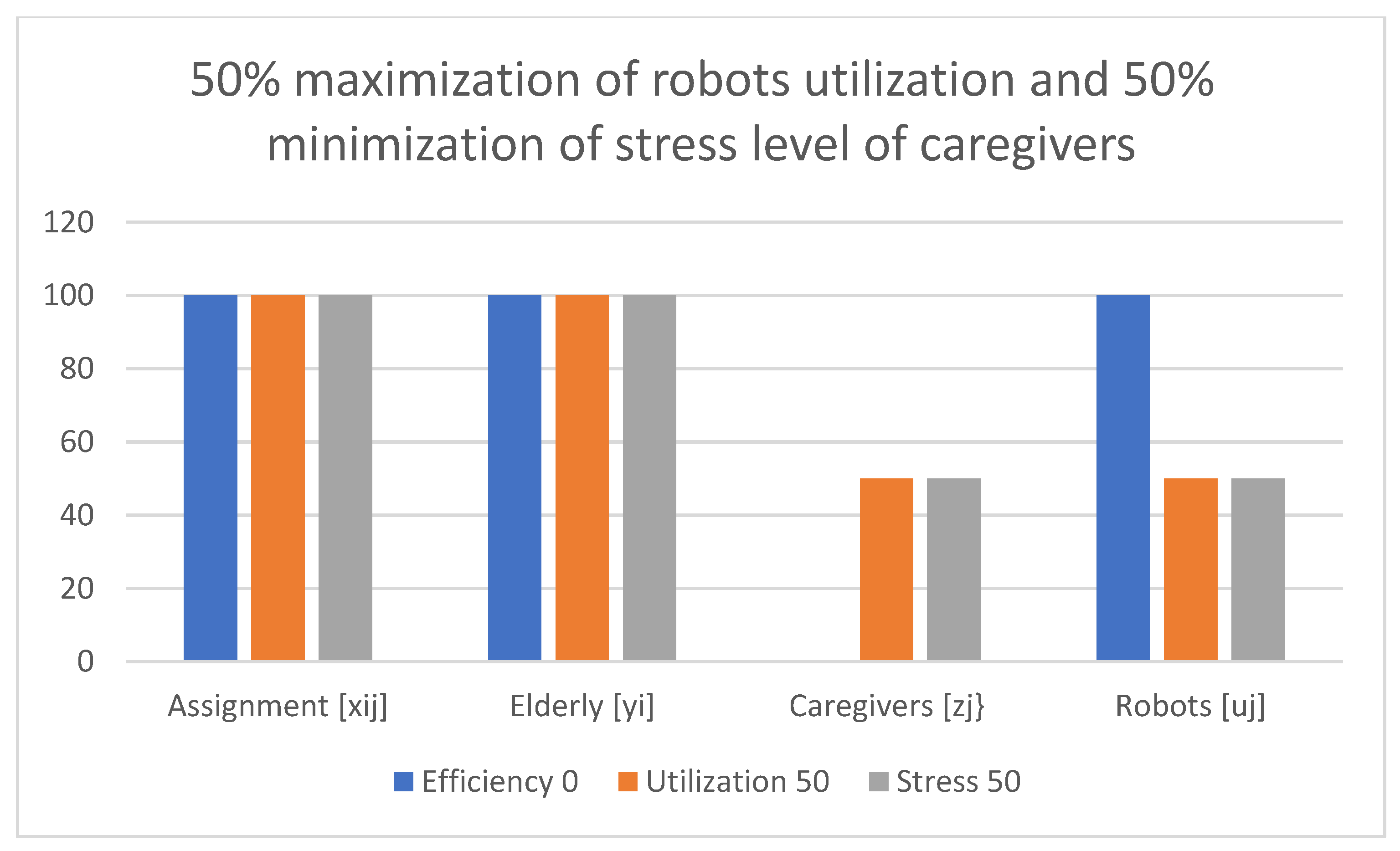

The Mathematical Programming Conceptual Optimization Model—Findings from Computational Experiments

8. Discussion

Four Categories from the Focus Groups

9. Limitations

10. Future Research

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclosure

Reporting

References

- Statistics Explained. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Lofqvist, C.; Granbom, M.; Himmelsbach, I.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F.; Haak, M. Voices on relocation and aging in place in very old age--a complex and ambivalent matter. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bien, B.; McKee, K.J.; Dohner, H.; Triantafillou, J.; Lamura, G.; Doroszkiewicz, H.; Krevers, B.; Kofahl, C. Disabled older people’s use of health and social care services and their unmet care needs in six european countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardaro, G.; Antonini, A.; Motta, E. Robots for Elderly Care in the Home: A Landscape Analysis and Co-Design Toolkit. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Iqbal, F.; Alam, T.M.; Aujla, G.K.; Devnath, L.; Khan, A.G.; Iqbal, R.; Shahzadi, I.; Rubab, A. The Impact of Artificial intelligence and Robotics on the Future Employment Opportunities. Trends Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2020, 5, 050–054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Sutherland, C.; Ahn, H.S.; MacDonald, B.A.; Peri, K.; Johanson, D.L.; Vajsakovic, D.S.; Kerse, N.; Broadbent, E. Developing assistive robots for people with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: A qualitative study with older adults and experts in aged care. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e031937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandemeulebroucke, T.; Dierckx de Casterlé, B.; Gastmans, C. How do older adults experience and perceive socially assistive robots in aged care: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 2z, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.; Boulay, M.; Jouen, F.; Rigaud, A.-S. “Are we ready for robots that care for us?” Attitudes and opinions of older adults toward socially assistive robots. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.J.; Li, P.-S.; Wang, C.-H.; Lin, S.-L.; Hsu, T.-C.; Tsai, C.-M.T. Socially Assistive Robots for People Living with Dementia in Long-Term Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Gerontology 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakostas, G.A.; Sidiropoulos, G.K.; Papadopoulou, C.I.; Vrochidou, E.; Kaburlasos, V.G.; Papadopoulou, M.T.; Holeva, V.; Nikopoulou, V.-A.; Dalivigkas, N. Social Robots in Special Education: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, G.; Petito, A.; Calvio, A.; Toto, G.A.; Limone, P. Robot Assistive Therapy Strategies for Children with Autism. In Psychology, Learning, Technology. PLT 2022. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Limone, P., Di Fuccio, R., Toto, G.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaf, S.; Draper, H.; Gelderblom, G.-J.; Sorell, T.; de Witte, L. Can a service robot which supports independent living of older people disobey a command? The views of older people, informal carers and professional caregivers on the acceptability of robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2016, 8, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Health and Aging—World Health Organization. National Institutes of Health. Available online: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Mast, M.; Burmester, M.; Kruger, K.; Fatikow, S.; Arbeiter, G.; Graf, B.; Kronreif, G.; Pigini, L.; Facal, D.; Qiu, R. User-centered design of a dynamic-autonomy remote interaction concept for manipulation-capable robots to assist elderly people in the home. J. Hum. Robot. Interact. 2012, 1, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, E.; Stafford, R.; MacDonald, B. Acceptance of healthcare robots for the older population: Review and future directions. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2009, 1, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsiga, K.; Edelmayer, G.; Rumeau, P.; Peter, O.; Toth, A.; Fazekas, G. Home care robot for socially supporting the elderly: Focus group studies in three european countries to screen user attitudes and requirements. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2013, 36, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezer, N.; Fisk, A.D.; Rogers, W.A. Attitudinal and intentional acceptance of domestic robots by younger and older adults. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5615, pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kachouie, R.; Sedighadeli, S.; Khosla, R.; Chu, M.-T. Socially assistive robots in elderly care: A mixed-method systematic literature review. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2014, 30, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.; MacDonald, B.; Broadbent, E. The role of healthcare robots for older people at home: A review. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2014, 6, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, A.; Lansley, P. Introducing assistive technology into the existing homes of older people: Feasibility, acceptability, costs and outcomes. J. Telemed. Telecare 2005, 11 (Suppl. 1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peek, S.T.; Wouters, E.J.; van Hoof, J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Boeije, H.R.; Vrijhoef, H.J. Factors influencing acceptance of technology for aging in place: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brebner, J.A.; Brebner, E.M.; Ruddick-Bracken, H. Experience-based guidelines for the implementation of telemedicine services. J. Telemed. Telecare 2005, 11 (Suppl. 1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobb, R.; Hilsen, P.; Ryan, P. Assessing technology needs for the elderly: Finding the perfect match for home. Home Healthc. Nurse 2003, 21, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekens, J.; Heerink, M.; Rosendal, H. Assistive social robots in elderly care: A review. Gerontechnology 2009, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Hayat, M.F.; Shaukat, K.; Alam, T.M.; Hameed, I.A.; Luo, S.; Basheer, S.; Ayadi, M.; Ksibi, A. A Proposed Framework for Early Prediction of Schistosomiasis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, A.; Awan, M.J.; Alshudukhi, J.; Alam, T.M.; Alhamazani, K.T.; Meraf, Z. Software Measurement by Using Artificial Intelligence. J. Nanomater. 2022, 7283171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B.; Płonka, J. Project and Prototype of Mobile Application for Monitoring the Global COVID-19 Epidemiological Situation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuczyńska, M.; Matthews-Kozanecka, M.; Baum, E. Accessibility to Non-COVID Health Services in the World During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 760795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dino, M.J.S.; Davidson, P.M.; Dion, K.W.; Szanton, S.L.; Ong, I.L. Nursing and human-computer interaction in healthcare robots for older people: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2022, 4, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B. Selected Multiple Criteria Supply Chain Optimization Problems. In Applications of Management Science; Lawrence, K.D., Pai, D.R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; Volume 20, pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharian, P.; Panchea, A.M.; Ferland, F. A Review on the Use of Mobile Service Robots in Elderly Care. Robotics 2022, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.; Therouanne, P.; Milhabet, I. The acceptability of social robots: A scoping review of the recent literature. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 137, 107419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandemeulebroucke, T.; Dzi, K.; Gastmans, C. Older adults’ experiences with and perceptions of the use of socially assistive robots in aged care: A systematic review of quantitative evidence. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 95, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhart, K. What Robots Can- and Can’t-Do for the Old and Lonely. The New Yorker. 2021, May 24th. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/05/31/what-robots-can-and-cant-do-for-the-old-and-lonely (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Shin, M.H.; McLaren, J.; Ramsey, A.; Sullivan, J.L.; Moo, L. Improving a Mobile Telepresence Robot for People With Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias: Semistructured Interviews With Stakeholders. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e32322. Available online: https://aging.jmir.org/2022/2/e32322 (accessed on 21 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Anderson, J.G.; Wyatt, T.H.; Lopez, R.P.; Crane, M.; Montgomery, A.; Zhao, X. Assessing the Acceptability of a Humanoid Robot for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia Care Using an Online Survey. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.; Gonçalves, F.; Garcia, I.S.; Lopes, G.; Ribeiro, A.F. CHARMIE: A Collaborative Healthcare and Home Service and Assistant Robot for Elderly Care. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradwell, H.; Edwards, K.J.; Winnington, R.; Thill, S.; Allgar, V.; Jones, R.B. Implementing Affordable Socially Assistive Pet Robots in Care Homes Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stratified Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial and Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e38864. Available online: https://aging.jmir.org/2022/3/e38864 (accessed on 21 April 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, W.Q.; Toomey, E.; Flynn, A.; Casey, D. Determinants of implementing pet robots in nursing homes for dementia care. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimova, B.; Toman, J.; Kuca, K. Effectiveness of the dog therapy for patients with dementia-a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, J.W.; Brophy, J.; Weese, J. Reducing the risk of pet-associated zoonotic infections. CMAJ 2015, 187, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordoch, E.; Osterreicher, A.; Guse, L.; Roger, K.; Thompson, G. Use of social commitment robots in the care of elderly people with dementia: A literature review. Maturitas 2013, 74, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. Service Robots: A Systematic Literature Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, C.; Kajikawa, Y. Using acknowledgement data to characterize funding organizations by the types of research sponsored: The case of robotics research. Scientometrics 2018, 114, 883–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, J.; Badu-Baiden, F.; Giroux, M.; Choi, Y. Preference for robot service or human service in hotels? Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.H.; Siddique, A.; Lee, C.W. Robotics Utilization for Healthcare Digitization in Global COVID-19 Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C.; Schöttler, M.; Hoffmann, C.P. The privacy implications of social robots: Scoping review and expert interviews. Mob. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Di Fava, A.; Vivas, C.; Marchionni, L.; Ferro, F. ARI: The Social Assistive Robot and Companion. In Proceedings of the 2020 29th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Naples, Italy, 31 August–4 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 745–751. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorini, L.; Tabeau, K.; D’Onofrio, G.; Coviello, L.; De Mul, M.; Sancarlo, D.; Fabbricotti, I.; Cavallo, F. Co-creation of an assistive robot for independent living: Lessons learned on robot design. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2020, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasola, J.; Mataric, M.J. Using socially assistive human–robot interaction to motivate physical exercise for older adults. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 2512–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittmann, R.; Fröhlich, T.; Schäfer, J.; Reiser, U.; Weißhardt, F.; Haug, A. Let me introduce myself: I am Care-O-bot 4, a gentleman robot. In Mensch und Computer 2015—Tagungsband—Mensch und Computer 2015–Proceedings; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Krakovski, M.; Kumar, S.; Givati, S.; Bardea, M.; Zafrani, O.; Nimrod, G.; Bar-Haim, S.; Edan, Y. “Gymmy”: Designing and Testing a Robot for Physical and Cognitive Training of Older Adults. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of Auckland. Healthbots. Available online: https://cares.blogs.auckland.ac.nz/research/healthcare-assistive-technologies/healthbots/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Fischinger, D.; Einramhof, P.; Papoutsakis, K.; Wohlkinger, W.; Mayer, P.; Panek, P.; Hofmann, S.; Koertner, T.; Weiss, A.; Argyros, A.; et al. Hobbit, a care robot supporting independent living at home: First prototype and lessons learned. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2016, 75, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, I.; Toprak, S.; Grenzing, A.; Hinz, T.; Auddy, S.; Karaoguz, E.C.; Chandran, A.; Remmels, M.; ElShinawi, A.; Josifovski, J.; et al. A Robotic Home Assistant with Memory Aid Functionality. In Proceedings of the Joint German/Austrian Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Künstliche Intelligenz), Klagenfurt, Austria, 26–30 September 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 102–115. [Google Scholar]

- Robosoft. Robots Introduction. Available online: https://kompairobotics.com/robot-kompai/ (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Gross, H.M.; Schroeter, C.; Müller, S.; Volkhardt, M.; Einhorn, E.; Bley, A.; Langner, T.; Merten, M.; Huijnen, C.; van den Heuvel, H.; et al. Further progress towards a home robot companion for people with mild cognitive impairment. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–17 October 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 637–644. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrobek, K.A.; Berger, E.H.; Van der Loos, H.M.; Salisbury, J.K. Towards A Personal Robotics Development Platform: Rationale and Design of An Intrinsically Safe Personal Robot. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 2165–2170. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier, C. Collaborative Robot Series: PR2 from Willow Garage. 2016. Available online: https://blog.robotiq.com/bid/65419/Collaborative-Robot-Series-PR2-from-Willow-Garage (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Costa, A.; Martinez-Martin, E.; Cazorla, M.; Julian, V. PHAROS—PHysical assistant RObot system. Sensors 2018, 18, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, E.; Costa, A.; Cazorla, M. PHAROS 2.0—A PHysical assistant RObot system improved. Sensors 2019, 19, 4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostavelis, I.; Giakoumis, D.; Peleka, G.; Kargakos, A.; Skartados, E.; Vasileiadis, M.; Tzovaras, D. RAMCIP Robot: A Personal Robotic Assistant; Demonstration of A Complete Framework. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; p. 743. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, T.; Ishiguro, H.; Imai, M.; Ono, T. Development and evaluation of interactive humanoid robots. Proc. IEEE 2004, 92, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, E.; Escalona, F.; Cazorla, M. Socially assistive robots for older adults and people with autism: An overview. Electronics 2020, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MetraLabs. SCITOS A5—Guide, Entertainer & Security. Available online: https://www.metralabs.com/en/service-robot-scitos-a5/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Pandey, A.K.; Gelin, R. A mass-produced sociable humanoid robot: Pepper: The first machine of its kind. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2018, 25, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Lu, M.J.; Tseng, S.H.; Fu, L.C. A companion robot for daily care of elders based on homeostasis. In Proceedings of the 2017 56th Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers of Japan (SICE), Kanazawa, Japan, 19–22 September 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1401–1406. [Google Scholar]

- PAL Robotics. TIAGo Technical Specifications. Available online: https://pal-robotics.com/datasheets/tiago (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Cosar, S.; Fernandez-Carmona, M.; Agrigoroaie, R.; Pages, J.; Ferland, F.; Zhao, F.; Yue, S.; Bellotto, N.; Tapus, A. ENRICHME: Perception and Interaction of an Assistive Robot for the Elderly at Home. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2020, 12, 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B. Applications of multi-criteria mathematical programming models for assignment of services in a hospital. In Applications of Management Science; Lawrence, K.D., Kleinman, G., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 16, pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B. A single and triple-objective mathematical programming models for assignment of services in a healthcare institution. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2013, 15, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cildoz, M.; Ibarra, A.; Mallor, F. Coping with stress in emergency department physicians through improved patient-flow management. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 71, 100828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohliver, A.; Ody-Brasier, A. Religious Affiliation and Wrongdoing: Evidence from U.S. Nursing Homes. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Fields, N.L.; Greer, J.A.; Tamplain, P.M.; Bricout, J.C.; Sharma, B.; Doelling, K.L. Socially assistive robotics and older family caregivers of young adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD): A pilot study exploring respite, acceptance, and usefulness. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cildoz, M.; Mallor, F.; Mateo, P.M. A GRASP-based algorithm for solving the emergency room physician scheduling problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 103, 107151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cildoz, M.; Ibarra, A.; Mallor, F. Accumulating priority queues versus pure priority queues for managing patients in emergency departments. Oper. Res. Health Care 2019, 23, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, A.; Fuentes-Aguilar, R.Q.; Salgado, I.; Chairez, I. A review on the application of autonomous and intelligent robotic devices in medical rehabilitation. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2022, 44, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B. A Three Stage Lexicographic Approach for Multi-Criteria Portfolio Optimization by Mixed Integer Programming. Przegląd. Elektrotechniczny. 2008, 84, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sawik, B. Bi-Criteria Portfolio Optimization Models with Percentile and Symmetric Risk Measures by Mathematical Programming. Przegląd. Elektrotechniczny. 2012, 88, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wallenius, J.; Dyer, J.S.; Fishburn, P.C.; Steuer, R.E.; Zionts, S.; Deb, K. Multiple criteria decision making, multiattribute utility theory: Recent accomplishments and what lies ahead. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.J.; Climaco, J. A review of interactive methods for multiobjective integer and mixed-integer programming. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 180, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cylkowska-Nowak, M.; Tobis, S.; Salatino, C.; Tapus, A.; Suwalska, A. The robot in elderly care. In 2nd International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM2015, Book 1; STEF92 Technology Ltd. (Sofia): Albena, Bulgaria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tobis, S.; Cylkowska-Nowak, M.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K.; Pawlaczyk, M.; Suwalska, A. Occupational therapy students’ perceptions of the role of robots in the care for older people living in the community. Occup. Ther. Int. 2017, 2017, 9592405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobis, S.; Salatino, C.; Tapus, A.; Suwalska, A.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. Opinions about robots in care for older people. In SGEM 4th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM 2017, SGEM 2017 Conference Proceedings; Ivanova, T., Koha, A., Ivanova, I., Eds.; Science & Society, Section, Sociology and Healthcare; STEF92 Technology Ltd. (Sofia): Albena, Bulgaria, 2017; Volume 3, Available online: https://www.sgemsocial.org/index.php/jresearch-article?citekey=Ivanova201712165172 (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Łukasik, S.; Tobis, S.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K.; Suwalska, A. Could robots help older people with age-related nutritional problems? Opinions of potential users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobis, S.; Neumann-Podczaska, A.; Kropinska, S.; Suwalska, A. UNRAQ—A Questionnaire for the Use of a Social Robot in Care for Older Persons. A Multi-Stakeholder Study and Psychometric Properties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszak, M.; Sawik, B.; Stańdo, J.; Baum, E. E-Learning as a Factor Optimizing the Amount of Work Time Devoted to Preparing an Exam for Medical Program Students during the COVID-19 Epidemic Situation. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukasik, S.; Tobis, S.; Suwalska, J.; Łojko, D.; Napierała, M.; Proch, M.; Neumann-Podczaska, A.; Suwalska, A. The Role of Socially Assistive Robots in the Care of Older People: To Assist in Cognitive Training, to Remind or to Accompany? Sustainability 2021, 13, 10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Podczaska, A.; Seostianin, M.; Madejczyk, K.; Merks, P.; Religioni, U.; Tomczak, Z.; Tobis, S.; Moga, D.C.; Ryan, M.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. An Experimental Education Project for Consultations of Older Adults during the Pandemic and Healthcare Lockdown. Healthcare 2021, 9, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnicki, M.; Neumann-Podczaska, A.; Seostianin, M.; Tomczak, Z.; Tariq, H.; Chudek, J.; Tobis, S.; Mozer-Lisewska, I.; Suwalska, A.; Tykarski, A.; et al. Long-Term Survival of Older Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19. Do Clinical Characteristics upon Admission Matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobis, S.; Piasek, J.; Cylkowska-Nowak, M.; Suwalska, A. Robots in Eldercare: How Does a Real-World Interaction with the Machine Influence the Perceptions of Older People? Sensors 2022, 22, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasadzka, E.; Tobis, S.; Trzmiel, T.; Marchewka, R.; Kozak, D.; Roksela, A.; Pieczyńska, A.; Hojan, K. Application of an EMG-Rehabilitation Robot in Patients with Post-Coronavirus Fatigue Syndrome (COVID-19)—A Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryszewska-Łabędzka, D.; Tobis, S.; Kropińska, S.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K.; Talarska, D. The Association of Self-Esteem with the Level of Independent Functioning and the Primary Demographic Factors in Persons over 60 Years of Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.M.; Shaukat, K.; Hameed, I.A.; Luo, S.; Sarwar, M.U.; Shabbir, S.; Li, J.; Khushi, M. An Investigation of Credit Card Default Prediction in the Imbalanced Datasets. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 201173–201198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded theory methodology. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Tawy, N.; Abdel-Kader, M. Revisiting the role of the grounded theory research methodology in the accounting information systems. In Proceedings of the European, Mediterranean & Middle Eastern Conference on Information Systems 2012 (EMCIS2012), Munich, Germany, 7–8 June 2022; Available online: https://bura.brunel.ac.uk/bitstream/2438/8435/2/Fulltext.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Robots: The More Europeans Know Them, the More They Like Them. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/news/robots-more-europeans-know-them-more-they-them (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Satariano, W.A.; Scharlach, A.E.; Lindeman, D. Aging, place, and technology: Toward improving access and wellness in older populations. J. Aging Health 2014, 26, 1373–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Cena, D.; Hernandez-Barrera, V.; Jimenez-Garcia, R.; Valle-Martin, B.; Fernandez-de-las-Penas, C.; Carrasco-Garrido, P. Has the prevalence of health care services use increased over the last decade (2001–2009) in elderly people? A spanish population-based survey. Maturitas 2013, 76, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edvardsson, D.; Winblad, B.; Sandman, P.O. Person-centred care of people with severe alzheimer’s disease: Current status and ways forward. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, B. Person-centredness in gerontological nursing: An overview of the literature. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabaczek, M. Aristotelian-Thomistic Contribution to the Contemporary Studies on Biological Life and Its Origin. Religions 2023, 14, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaczek, M. Contemporary Version of the Monogenetic Model of Anthropogenesis—Some Critical Remarks from the Thomistic Perspective. Religions 2023, 14, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B.; Serrano-Hernandez, A.; Muro, A.; Faulin, J. Multi-Criteria Simulation-Optimization Analysis of Usage of Automated Parcel Lockers: A Practical Approach. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, T.; Sawik, B. A rough cut cybersecurity investment using portfolio of security controls with maximum cybersecurity value. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 6556–6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B.; Faulin, J.; Serrano-Hernandez, A.; Ballano, A. A Simulation-Optimization Model for Automated Parcel Lockers Network Design in Urban Scenarios in Pamplona (Spain), Zakopane, and Krakow (Poland). In Proceedings of the 2022 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Singapore, 11–14 December 2022; pp. 1648–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, N. Robots rise to meet the challenge of caring for old people. Nature 2022, 601, S8–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Decision Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| xij | 1 if Robot/Caregiver j ∈ J is assigned to Elderly i ∈ I, 0 otherwise |

| yi | 1 if Elderly is considered i ∈ I, 0 otherwise |

| zj | 1 if Caregiver is considered j ∈ J, 0 otherwise |

| uj | 1 if Robot is considered j ∈ J, 0 otherwise |

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Weight for criterion k ∈ K in the multi-criteria objective function | |

| cij | Assignment efficiency for robot/caregiver j ∈ J to elderly i ∈ I |

| aij | Level of robot j ∈ J utilization, while serving elderly i ∈ I |

| bij | Caregiver j ∈ J stress level, while helping elderly j ∈ J |

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Efficiency of assignment of all robots/caregivers to all elderly | |

| Level of all robots’ utilization, while serving all elderly | |

| All caregivers’ stress level, while helping all elderly |

| Focus Group | Age (Years) /Sex | Former Profession | Focus Group | Age (Years) /Sex | Role | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65+ #1 | 1 | 78 (F) | Shop-assistant | Informal caregivers | A | 51 (F) | Caring for a family member |

| 2 | 77 (F) | Administrative employee | B | 21 (F) | |||

| 3 | 82 (M) | Engineer—designer | C | 21 (F) | |||

| 4 | 68 (F) | Tailor | D | 21 (F) | |||

| 5 | 86 (M) | Bookbinder | E | 69 (F) | |||

| 6 | 73 (F) | Graphic designer | F | 70 (M) | |||

| 65+ #2 | 7 | 76 (F) | Biochemist | Formal caregivers | G | 41 (F) | Physiotherapist |

| 8 | 87 (F) | Office employee | H | 52 (F) | Nurse | ||

| 9 | 77 (F) | Government employee | I | 53 (M) | Art therapist | ||

| 10 | 79 (F) | Surveyor technician | J | 32 (F) | Psychologist | ||

| 11 | 66 (M) | Company CEO | K | 51 (F) | Social worker | ||

| 12 | 70 (M) | Postman | L | 45 (F) | Nurse |

| Category | Subcategory | Examples | Citations from the Discussions of Older Persons |

|---|---|---|---|

| User’s characteristics | Psychosocial issues | Loneliness, companionship, ability to operate the robot | The robot would give “a sense of security when one is lonely (...) because I would like to wake up thinking that one is already there; one would feel less lonely with a robot” (1) |

| Medical issues | Multimorbidity, cognitive impairment, disabilities | “He has illnesses, diabetes and hypertension, and he does not remember much and he is upset about it, so this robot would be very much needed by him” (8) | |

| Robot’s characteristics | Appearance | Humanoid or machine-like, head/face, skin/fur (tactile features) | “I think it is good that it does not resemble a human being, that it actually looks like a machine, because if it had limbs, even immobile ones, it would be scary” (B) “I was thinking about some fur, the robot can be rendered more humanoid, dressed, decorated” (H) |

| Capabilities | Customizable, individualized for the user | “It must not be a blabber, after all, it is there to keep the secret, not to betray to outside” (2) | |

| Robot’s functions | Assistive functions | Home safety, housekeeping, food preparation, being informative, help with reading, praying together | “When it comes to cleaning, [the robot] cleans only in the middle, not in the corners.” “It is not able because it’s a manual thing, to bend over and yet make an effort” (9) |

| Health-related functions | Reminders (medications, doctor appointments), monitoring of life parameters, keeping medical records, physical exercises, cognitive games | “If you faint and the ambulance comes, it could tell the doctor what is wrong with you, it could have your medical history inside” (11) | |

| Social functions | Contact with the outside world, entertainment (playing cards, music replay) | “I would like it to read some books, a chapter every other day, because everyone has his eyes tired” (9) | |

| Barriers to overcome | Ethical issues | Control over the robot, access to observational data, the right to disobey the user’s command | “If someone sponsored such a robot to me, I would have a feeling that I was under control” (11) |

| Fears | High price tag, the risk of breakdown, loss of abilities if routine jobs are performed by the robot | The robot “will do what one does not want to do, whether one is sleepy, one wants to rest, and it will just be doing other things and disturbing” (6) | |

| Introduction | Gradual, staged introduction, pace of introduction matching the user’s capabilities, presence of a human assistant on-site (as long as necessary) | At the beginning “there would have to be another person there because I would be afraid to remain with it alone” (6), “to learn how to live together” (2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sawik, B.; Tobis, S.; Baum, E.; Suwalska, A.; Kropińska, S.; Stachnik, K.; Pérez-Bernabeu, E.; Cildoz, M.; Agustin, A.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. Robots for Elderly Care: Review, Multi-Criteria Optimization Model and Qualitative Case Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091286

Sawik B, Tobis S, Baum E, Suwalska A, Kropińska S, Stachnik K, Pérez-Bernabeu E, Cildoz M, Agustin A, Wieczorowska-Tobis K. Robots for Elderly Care: Review, Multi-Criteria Optimization Model and Qualitative Case Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(9):1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091286

Chicago/Turabian StyleSawik, Bartosz, Sławomir Tobis, Ewa Baum, Aleksandra Suwalska, Sylwia Kropińska, Katarzyna Stachnik, Elena Pérez-Bernabeu, Marta Cildoz, Alba Agustin, and Katarzyna Wieczorowska-Tobis. 2023. "Robots for Elderly Care: Review, Multi-Criteria Optimization Model and Qualitative Case Study" Healthcare 11, no. 9: 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091286

APA StyleSawik, B., Tobis, S., Baum, E., Suwalska, A., Kropińska, S., Stachnik, K., Pérez-Bernabeu, E., Cildoz, M., Agustin, A., & Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. (2023). Robots for Elderly Care: Review, Multi-Criteria Optimization Model and Qualitative Case Study. Healthcare, 11(9), 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091286