Factors Affecting the Public Intention to Repeat the COVID-19 Vaccination: Implications for Vaccine Communication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

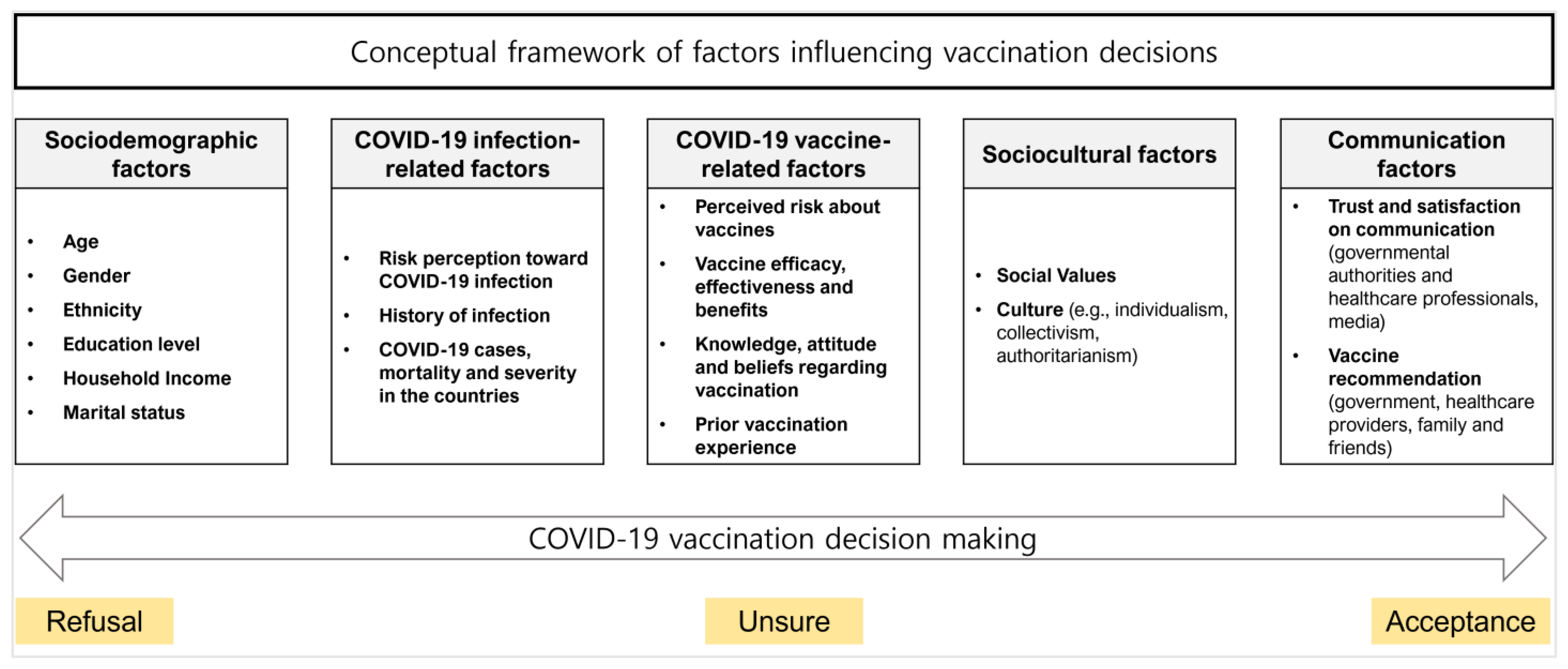

2.2.2. Independent Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Differences in Variables That Affect Intention to Repeat COVID-19 Vaccination

3.3. Factors Associated with Intention to Repeat COVID-19 Vaccination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO (World Health Organization). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Perra, N. Non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Phys. Rep. 2021, 913, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bok, K.; Sitar, S.; Graham, B.S.; Mascola, J.R. Accelerated COVID-19 vaccine development: Milestones, lessons, and prospects. Immunity 2021, 54, 1636–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyon, N. COVID-19 Vaccination Intent Has Risen in the Past Few Weeks. Ipsos 9 February 2021. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en/global-attitudes-covid-19-vaccine-january-2021 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Multilevel determinants of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: A rapid systematic review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 25, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Lee, S.H. COVID-19 vaccine refusal associated with health literacy: Findings from a population-based survey in Korea. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaire, A.; Panthee, B.; Basyal, D.; Paudel, A.; Panthee, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: A Case Study from Nepal. COVID 2022, 2, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, M.M.; Opel, D.J.; Benjamin, R.M.; Callaghan, T.; DiResta, R.; Elharake, J.A.; Flowers, L.C.; Galvani, A.P.; Salmon, D.A.; Schwartz, J.L. Effectiveness of vaccination mandates in improving uptake of COVID-19 vaccines in the USA. Lancet 2022, 400, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.L.; Oh, J. COVID-19 vaccination program in South Korea: A long journey toward a new normal. Health Policy Technol. 2022, 11, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Shao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: A literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 114, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Iuliano, A.D.; Brunkard, J.M.; Boehmer, T.K.; Peterson, E.; Adjei, S.; Binder, A.M.; Cobb, S.; Graff, P.; Hidalgo, P.; Panaggio, M.J. Trends in disease severity and health care utilization during the early Omicron variant period compared with previous SARS-CoV-2 high transmission periods—United States, December 2020–January 2022. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrovitz, N.; Ware, H.; Ma, X.; Li, Z.; Hosseini, R.; Cao, C.; Selemon, A.; Whelan, M.; Premji, Z.; Issa, H.; et al. Protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and hybrid immunity against the omicron variant and severe disease: A systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellyatt, H. Back to Reality at Last? Covid Rules Are Being Dropped in Europe Despite High Omicron Spread. CNBC, 27 January 2022. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/27/covid-rules-are-being-dropped-in-europe-despite-high-omicron-spread.html (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Marks, P.; Woodcock, J.; Califf, R. COVID-19 vaccination—Becoming part of the new normal. JAMA 2022, 327, 1863–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Kamarulzaman, A.; El-Mohandes, A. A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, E.; MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine acceptance: Barriers, perceived risks, benefits, and irrational beliefs. In The Vaccine Book; Bloom, B.R., Lambert, P.H., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 507–528. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, R.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Takahashi, M.; Luu, L.A.N.; Borsfay, K.; Kovács, M.; Hou, W.K.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Levin, Y. Psychological factors underpinning vaccine willingness in Israel, Japan and Hungary. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.; Kaur, M.; Kaur, R.; Grover, A.; Nash, D.; El-Mohandes, A. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance, Intention, and Hesitancy: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 698111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Matos, I.; Mandal, S. Annex A: COVID-19 Vaccine and Health Inequalities: Considerations for Prioritisation and Implementation; Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2021.

- Jennings, W.; Stoker, G.; Bunting, H.; Valgarðsson, V.O.; Gaskell, J.; Devine, D.; McKay, L.; Mills, M.C. Lack of Trust, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Social Media Use Predict COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Mariolis-Sapsakos, T.; Kaitelidou, D. First COVID-19 Booster Dose in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Willingness and Its Predictors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.H.; Park, A.K.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.A.; No, J.S.; Lee, C.; Rhee, J.E.; Kim, E.J. Status and characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 variant outbreak in the Republic of Korea in January 2021. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2022, 15, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KDCA (Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency). COVID-19 Booster Shot Guideline for Foreign Nationals Staying in the Republic of Korea; KDCA: Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2022. Available online: https://ncv.kdca.go.kr/board.es?mid=a12105000000&bid=0035&act=view&list_no=673 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Estimates of Vaccine Hesitancy for COVID-19; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- KDCA. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) VIII; KDCA: Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; You, M. It’s Politics, Isn’t It? Investigating Direct and Indirect Influences of Political Orientation on Risk Perception of COVID-19. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, J. Authoritarianism and group identification: A new view of an old construct. Political Psychol. 1989, 10, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.; Wildavsky, A. Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Dangers; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Marris, C.; Langford, I.H.; O’Riordan, T. A quantitative test of the cultural theory of risk perceptions: Comparison with the psychometric paradigm. Risk Anal. 1998, 18, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamel, L.; Kirzinger, A.; Muñana, C.; Brodie, M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020; Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CDCH (Central Disease Control Headquarters). Status of the COVID-19 Outbreak in South Korea (Regular Briefing on 5 May); KDCA: Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2020. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=354363&page=1 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Sprengholz, P.; Betsch, C.; Böhm, R. Reactance revisited: Consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID-19. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2021, 13, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, K.P.Y.; Ho, J.C.W.; Cheung, M.-C.; Ng, K.-C.; Ching, R.H.H.; Lai, K.-l.; Kam, T.T.; Gu, H.; Sit, K.-Y.; Hsin, M.K.Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature 2022, 603, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.; Newall, M.; Duran, J.; Rollason, C.; Golden, J. Most Americans Not Worrying about COVID Going into 2022 Holidays. Ipsos 6 December 2022. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/axios-ipsos-coronavirus-index (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- The Cabinet Office. COVID-19 Response: Living with COVID-19; The Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2022.

- Zhou, L.; Yan, W.; Li, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Lu, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Cost-effectiveness of interventions for the prevention and control of COVID-19: Systematic review of 85 modelling studies. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 05022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reifferscheid, L.; Lee, J.S.W.; MacDonald, N.E.; Sadarangani, M.; Assi, A.; Lemaire-Paquette, S.; MacDonald, S.E. Transition to endemic: Acceptance of additional COVID-19 vaccine doses among Canadian adults in a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Gallant, A.; Brown, L.; Corrigan, K.; Crowe, K.; Hendry, E. Barriers and facilitators to the future uptake of regular COVID-19 booster vaccinations among young adults in the UK. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2129238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzer, J.; Birmann, B.M.; Steffelbauer, I.; Bertau, M.; Zenk, L.; Caniglia, G.; Laubichler, M.D.; Steiner, G.; Schernhammer, E.S. Willingness to receive an annual COVID-19 booster vaccine in the German-speaking D-A-CH region in Europe: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 18, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuhammad, S.; Khabour, O.F.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Hamaideh, S.; Alzoubi, B.A.; Telfah, W.S.; El-zubi, F.K. The public’s attitude to and acceptance of periodic doses of the COVID-19 vaccine: A survey from Jordan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Appendices to the Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior–A systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Testing four competing theories of health-protective behavior. Health Psychol. 1993, 12, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Yan, W.; Tao, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. The Association between Risk Perception and Hesitancy toward the Booster Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine among People Aged 60 Years and Older in China. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shmueli, L. Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds-Tylus, T. Psychological reactance and persuasive health communication: A review of the literature. Front. Commun. 2019, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COVID-19 Vaccines: Safety Surveillance Manual; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). Enhancing Public Trust in COVID-19 Vaccination: The Role of Governments; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- KDCA. The KDCA’s COVID-19 Risk Communication; KDCA: Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2022.

- CDMH (Central Disaster Management Headquarters). Results of a Survey on COVID-19 Perception (July); MOHW (Ministry of Health and Welfare): Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&BOARD_ID=140&BOARD_FLAG=00&CONT_SEQ=366709 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Luo, C.; Chen, H.X.; Tung, T.H. COVID-19 vaccination in China: Adverse effects and its impact on health care working decisions on booster dose. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.B.; Bor, A.; Jørgensen, F.; Lindholt, M.F. Transparent communication about negative features of COVID-19 vaccines decreases acceptance but increases trust. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2024597118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quick, B.L.; Considine, J.R. Examining the use of forceful language when designing exercise persuasive messages for adults: A test of conceptualizing reactance arousal as a two-step process. Health Commun. 2008, 23, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. Communicating about Vaccine Safety: Guidelines to Help Health Workers Communicate with Parents, Caregivers, and Patients; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Hyland-Wood, B.; Gardner, J.; Leask, J.; Ecker, U.K.H. Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zou, H.; Song, Y.; Ren, L.; Xu, Y. Understanding the continuous vaccination of the COVID-19 vaccine: An empirical study from China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4954–4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, C.O.L.; Hu, Y.; Hu, H.; Bian, Y. Investigating the intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccination in Macao: Implications for vaccination strategies. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilewicz, M.; Soral, W. The politics of vaccine hesitancy: An ideological dual-process approach. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2021, 13, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, R.; Betsch, C. Prosocial vaccination. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 43, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intention to Repeat COVID-19 Vaccination | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Subjects | Hesitant/Unsure | Acceptance | t-Test/Χ2 | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | p-Value | |

| 1000 | 100.0 | 211 | 100 | 789 | 100 | ||

| Sex | 0.750 | ||||||

| Male | 505 | 50.5 | 104 | 49.3 | 401 | 50.8 | |

| Female | 495 | 49.5 | 107 | 50.7 | 388 | 49.2 | |

| Age (M(SD)) | 46.2 (14.8) | 42.1 (15.4) | 47.3 (14.4) | <0.001 *** | |||

| 18–29 years | 182 | 18.2 | 58 | 27.5 | 124 | 15.7 | |

| 30–39 years | 165 | 16.5 | 44 | 20.8 | 121 | 15.3 | |

| 40–49 years | 199 | 19.9 | 36 | 17.1 | 163 | 20.7 | |

| 50–59 years | 201 | 20.1 | 30 | 14.2 | 171 | 21.7 | |

| ≥60 years | 253 | 25.3 | 43 | 20.4 | 210 | 26.6 | |

| Education | 0.290 | ||||||

| Less than High school | 231 | 23.1 | 55 | 26.1 | 176 | 22.3 | |

| College and above | 769 | 76.9 | 156 | 73.9 | 613 | 77.7 | |

| Marital Status | 0.001 ** | ||||||

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 397 | 39.7 | 105 | 49.8 | 292 | 37.0 | |

| Married | 603 | 60.3 | 106 | 50.2 | 497 | 63.0 | |

| Monthly Household Income† | 0.214 | ||||||

| <3.00 | 203 | 20.3 | 49 | 23.2 | 154 | 19.5 | |

| 3.00–4.99 | 280 | 28.0 | 48 | 22.8 | 232 | 29.4 | |

| 5.00–6.99 | 249 | 24.9 | 58 | 27.5 | 191 | 24.2 | |

| ≥7.00 | 268 | 26.8 | 56 | 26.5 | 212 | 26.9 | |

| Health status (Chronic Disease) | 0.007 ** | ||||||

| No | 531 | 53.1 | 130 | 61.6 | 401 | 50.8 | |

| Yes | 469 | 46.9 | 81 | 38.4 | 388 | 49.2 | |

| Risk Perception (M(SD)) | 3.09 (0.64) | 2.91 (0.74) | 3.14 (0.60) | <0.001 *** | |||

| History of Infection | 0.935 | ||||||

| No | 692 | 69.2 | 147 | 69.7 | 545 | 69.1 | |

| Yes | 308 | 30.8 | 64 | 30.3 | 244 | 30.9 | |

| Vaccination Status | <0.001 *** | ||||||

| 0 | 70 | 7.0 | 52 | 24.6 | 18 | 2.3 | |

| 1–2 | 402 | 40.2 | 70 | 46.0 | 305 | 38.7 | |

| 3 (booster shot) | 52 | 52.8 | 62 | 29.4 | 466 | 59.0 | |

| Vaccine adverse events | <0.001 *** | ||||||

| No | 381 | 38.1 | 58 | 27.5 | 323 | 40.9 | |

| Yes | 619 | 61.9 | 153 | 72.5 | 466 | 59.1 | |

| Political ideology | <0.001 *** | ||||||

| Conservative | 189 | 18.9 | 55 | 26.1 | 134 | 17.0 | |

| Moderate | 584 | 58.4 | 122 | 57.8 | 462 | 58.5 | |

| Liberal | 190 | 19.0 | 23 | 10.9 | 167 | 21.2 | |

| Don’t know | 37 | 3.7 | 11 | 5.2 | 26 | 3.3 | |

| Authoritarian attitude (M (SD)) | 3.49 (0.73) | 3.09 (0.82) | 3.60 (0.66) | <0.001 *** | |||

| Collective responsibility | <0.001 *** | ||||||

| Personal Choice | 213 | 21.3 | 119 | 56.4 | 94 | 11.9 | |

| Everyone’s responsibility | 408 | 40.8 | 27 | 12.8 | 381 | 48.3 | |

| Both | 349 | 34.9 | 53 | 25.1 | 296 | 37.5 | |

| Neither | 9 | 0.9 | 5 | 2.4 | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Don’t know | 21 | 2.1 | 7 | 3.3 | 14 | 1.8 | |

| Attitude on regular briefing (M (SD)) | 3.22 (0.89) | 2.58 (0.91) | 3.39 (0.80) | <0.001 *** | |||

| Psychological reactance against the government’s vaccination recommendation (M (SD)) | 4.71 (1.58) | 5.79 (1.44) | 4.42 (1.49) | <0.001 *** | |||

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 0.94 (0.69–1.28) | 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | 1.03 (0.73–1.45) | 0.91 (0.62–1.34) | 0.89 (0.60–1.31) |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) ** | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) ** | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) |

| Education | |||||

| Less than High school | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| College and above | 1.43 (0.99–2.06) | 1.42 (0.98–2.06) | 1.29 (0.85–1.93) | 1.28 (0.80–2.02) | 1.32 (0.82–2.11) |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Married | 1.22 (0.83–1.78) | 1.18 (0.80–1.74) | 1.44 (0.95–2.18) | 1.5 (0.95–2.38) | 1.6 (0.99–2.56) |

| Monthly Household Income | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) |

| Health status (Chronic Disease) | |||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.29 (0.93–1.81) | 1.24 (0.88–1.73) | 1.37 (0.95–1.99) | 1.37 (0.91–2.08) | 1.41 (0.92–2.17) |

| Risk perception | 1.63 (1.29–2.06) *** | 1.61 (1.24–2.09) *** | 1.33 (1.01–1.77) * | 1.28 (0.95–1.71) | |

| History of Infection | |||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.00 (0.72–1.42) | 1.05 (0.73–1.52) | 1.04 (0.70–1.56) | 1.11 (0.73–1.69) | |

| Vaccination status | |||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| 1–2 | 8.82 (4.91–16.51) *** | 5.51 (2.85–11.01) *** | 5.13 (2.61–10.42) *** | ||

| 3 | 18.91 (10.34–35.98) *** | 7.35 (3.69–15.04) *** | 6.29 (3.10–13.09) *** | ||

| Vaccine adverse events | |||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.48 (0.33–0.69) *** | 0.51 (0.33–0.77) ** | 0.53 (0.34–0.82) ** | ||

| Political ideology | |||||

| Conservative | Ref | Ref | |||

| Moderate | 1.44 (0.89–2.30) | 1.27 (0.78–2.06) | |||

| Liberal | 1.76 (0.92–3.43) | 1.17 (0.59–2.36) | |||

| Don’t know | 0.77 (0.31–1.97) | 0.63 (0.25–1.68) | |||

| Authoritarian attitude | 1.60 (1.22–2.10) ** | 1.22 (0.91–1.65) | |||

| Collective responsibility | |||||

| Personal choice | Ref | Ref | |||

| Everyone’s responsibility | 8.44 (5.00–14.58) *** | 4.83 (2.75–8.61) *** | |||

| Both | 4.23 (2.71–6.66) *** | 3.08 (1.92–4.96) *** | |||

| Neither | 1.30 (0.25–6.66) | 1.18 (0.23–5.91) | |||

| Don’t know | 1.71 (0.63–5.01) | 1.40 (0.50–4.16) | |||

| Attitude on regular briefing | 1.56 (1.20–2.03) ** | ||||

| Psychological reactance against the government’s vaccination recommendation | 0.74 (0.63–0.86) *** | ||||

| R2 Tjur | 0.028 | 0.047 | 0.186 | 0.311 | 0.346 |

| ΔR2 | 0.019 *** | 0.139 *** | 0.125 *** | 0.035 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.; Park, K.; Shin, J.; Oh, J.; Jang, Y.; You, M. Factors Affecting the Public Intention to Repeat the COVID-19 Vaccination: Implications for Vaccine Communication. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091235

Lee Y, Park K, Shin J, Oh J, Jang Y, You M. Factors Affecting the Public Intention to Repeat the COVID-19 Vaccination: Implications for Vaccine Communication. Healthcare. 2023; 11(9):1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091235

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yubin, Kunhee Park, Jeonghoon Shin, Jeonghyeon Oh, Yeongeun Jang, and Myoungsoon You. 2023. "Factors Affecting the Public Intention to Repeat the COVID-19 Vaccination: Implications for Vaccine Communication" Healthcare 11, no. 9: 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091235

APA StyleLee, Y., Park, K., Shin, J., Oh, J., Jang, Y., & You, M. (2023). Factors Affecting the Public Intention to Repeat the COVID-19 Vaccination: Implications for Vaccine Communication. Healthcare, 11(9), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091235