Transforming Health Care Delivery towards Value-Based Health Care in Germany: A Delphi Survey among Stakeholders

Abstract

1. Introduction

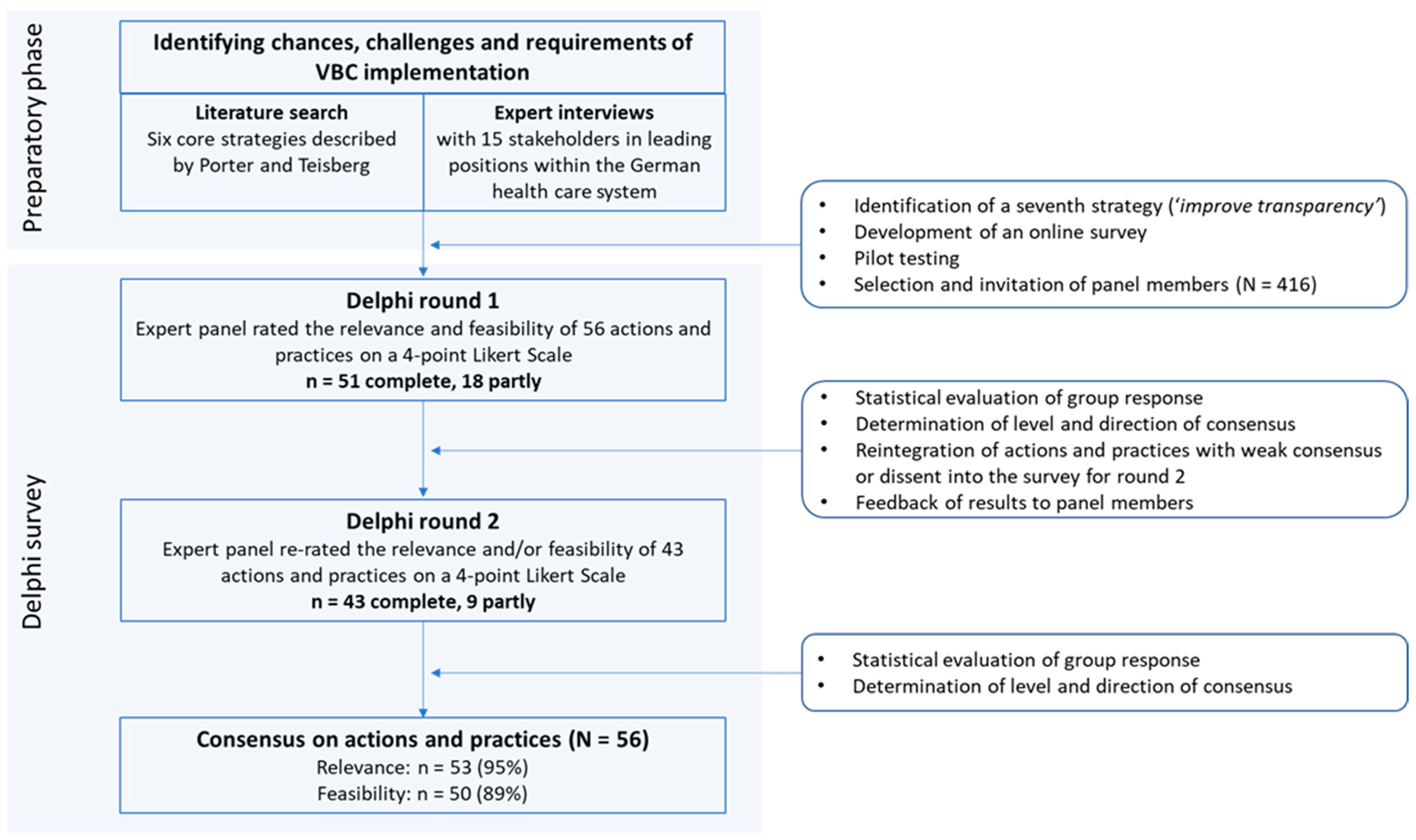

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Delphi Study

2.2. Development of the Survey

2.3. The Panel Members

2.4. Data Analysis and Definition of Consensus

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD (Ed.) Health Expenditure in Relation to GDP. In Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 188–189. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Pressemitteilung Nr. 167 Vom 6. April 2021; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021.

- Porter, M.E.; Teisberg, E.O. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9781591397786. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.; Lee, T. The Strategy That Will Fix Health Care. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, P.; Savage, C.; Thor, J.; Atun, R.; Carlsson, K.S.; Makdisse, M.; Neto, M.C.; Klajner, S.; Parini, P.; Mazzocato, P. It takes two to dance the VBHC tango: A multiple case study of the adoption of value-based strategies in Sweden and Brazil. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 282, 114145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cossio-Gil, Y.; Omara, M.; Watson, C.; Casey, J.; Chakhunashvili, A.; Gutiérrez-San Miguel, M.; Kahlem, P.; Keuchkerian, S.; Kirchberger, V.; Luce-Garnier, V.; et al. The Roadmap for Implementing Value-Based Healthcare in European University Hospitals—Consensus Report and Recommendations. Value Health 2021, 25, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mjåset, C.; Ikram, U.; Nagra, N.S. Value-Based Health Care in Four Different Health Care Systems. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2020, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsdal, H.; Bjørkquist, C. Value-based innovations in a Norwegian hospital: From conceptualization to implementation. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 1717–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Boston Consulting Group. How Dutch Hospitals Make Value-Based Health Care Work; The Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, T.; Bott, N.; Thwaites, R.; Mosor, E.; Andrews, M.R.; Borgdorff, J.; Cossio-Gil, Y.; de Portu, S.; Ferrante, M.; Fischer, F.; et al. Building a Value-Based Care Infrastructure in Europe: The Health Outcomes Observatory. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2021, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kuck, A.; Kinscher, K.; Fehring, L.; Hildebrandt, H.; Doerner, J.; Lange, J.; Truebel, H.; Boehme, P.; Bade, C.; Mondritzki, T. Healthcare Providers’ Knowledge of Value-Based Care in Germany: An Adapted, Mixed-Methods Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jünger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. (Eds.) The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 0201042940. [Google Scholar]

- Holey, E.A.; Feeley, J.L.; Dixon, J.; Whittaker, V.J. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, I.R.; Grant, R.C.; Feldman, B.M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Ling, S.C.; Moore, A.M.; Wales, P.W. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoff, M. The design of a policy Delphi. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1970, 2, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, R.; Kelly, A. Equity in resource allocation in the Irish health service. A policy Delphi study. Health Policy 2004, 67, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, R.A. The Policy Delphi: A Method for Identifying Intended and Unintended Consequences of Educational Policy. Policy Futur. Educ. 2013, 11, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoff, M. The Policy Delphi. In The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Linstone, H.A., Turoff, M., Eds.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 80–96. ISBN 0201042940. [Google Scholar]

- De Loë, R.C.; Melnychuk, N.; Murray, D.; Plummer, R. Advancing the State of Policy Delphi Practice: A Systematic Review Evaluating Methodological Evolution, Innovation, and Opportunities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, R.D.; de Loë, R.C. The Policy Delphi: Purpose, Structure, and Application. Can. Geogr. 1990, 34, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Unser Gesundheitssystem. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/5_Publikationen/Gesundheit/Flyer_Poster_etc/221213_BMG_Infografik_Gesundheitssystem_382x520_barrierefrei.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- De Loë, R.C. Exploring complex policy questions using the policy Delphi. Appl. Geogr. 1995, 15, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Guth, C. Redefining German Health Care: Moving to a Value-Based System; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-642-10826-6. [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund, N.; Lawyer, P.; Larsson, S.; Kent, J. Progress Towards Value-Based Healthcare: Lessons from 12 Countries. 2012. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2012/health-care-public-sector-progress-toward-value-based-health-care (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Bratan, T.; Schneider, D.; Heyen, N.; Pullmann, L.; Friedewald, M.; Kuhlmann, D.; Brkic, N.; Hüsing, B. E-Health in Deutschland: Entwicklungsperspektiven und Internationaler Vergleich. 2022. Available online: https://www.e-fi.de/fileadmin/Assets/Studien/2022/StuDIS_12_2022.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Rosalia, R.A.; Wahba, K.; Milevska-Kostova, N. How digital transformation can help achieve value-based healthcare: Balkans as a case in point. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 4, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kaplan, R.S. How to pay for health care. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- EIT Health. In Implementing Value-Based Health Care in Europe: Handbook for Pioneers; EIT KIC Publications: Budapest, Hungary, 2020.

- Larsson, S.; Lawyer, P.; Garellick, G.; Lindahl, B.; Lundström, M. Use of 13 disease registries in 5 countries demonstrates the potential to use outcome data to improve health care’s value. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, P.; Vukovic, V.; Parente, P.; Sulejmani, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Specchia, M.L. The impact of Public Reporting on clinical outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, D.Y.; Fremes, S.E. Commentary: Who benefits from public reporting of outcomes in coronary surgery? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbeck, V.; Ernst, S.-C.; Pross, C. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures—An International Comparison: Challenges and Success Strategies for the Implementation in Germany; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Richtlinie des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses zur Datengestützten Einrichtungsübergreifenden Qualitätssicherung: DeQS-RL; Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pross, C.; Geissler, A.; Busse, R. Measuring, Reporting, and Rewarding Quality of Care in 5 Nations: 5 Policy Levers to Enhance Hospital Quality Accountability. Milbank Q. 2017, 95, 136–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmann, G.; Delnoij, D.; van de Bovenkamp, H.; Groote, R.; Ahaus, K. Expert consensus on moving towards a value-based healthcare system in the Netherlands: A Delphi study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.; Bååthe, F.; Andersson, A.E.; Wikström, E.; Sandoff, M. Experiences from implementing value-based healthcare at a Swedish University Hospital—An longitudinal interview study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leusder, M.; Porte, P.; Ahaus, K.; van Elten, H. Cost measurement in value-based healthcare: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e066568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Anderson, S.R. Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing. SSRN J. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etges, A.P.B.d.S.; Ruschel, K.B.; Polanczyk, C.A.; Urman, R.D. Advances in Value-Based Healthcare by the Application of Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing for Inpatient Management: A Systematic Review. Value Health 2020, 23, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niñerola, A.; Hernández-Lara, A.-B.; Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V. Improving healthcare performance through Activity-Based Costing and Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2021, 36, 2079–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Larsson, S.; Lee, T.H. Standardizing Patient Outcomes Measurement. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Delphi Survey | Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 51 | n = 43 | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 19 | 37% | 16 | 37% |

| Female | 31 | 61% | 27 | 63% |

| Age | ||||

| 20–29 years | 2 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| 30–39 years | 9 | 18% | 12 | 28% |

| 40–49 years | 11 | 21% | 6 | 14% |

| 50–59 years | 21 | 41% | 16 | 37% |

| 60–69 years | 8 | 16% | 9 | 21% |

| n | % * | n | % * | |

| Work area | ||||

| Hospital and corresponding associations | 15 | 29% | 19 | 44% |

| Statutory health insurance and corresponding associations | 10 | 20% | 6 | 14% |

| Physician’s representation of interests | 5 | 10% | 1 | 2% |

| Medical management in a care facility | 3 | 6% | 4 | 9% |

| Commercial management in a care facility | 2 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Nursing management in a care facility | 0 | 0% | 2 | 5% |

| Pharmacies’ representation of interests | 3 | 6% | 2 | 5% |

| Patient representation | 2 | 4% | 1 | 2% |

| Institution of quality assessment in health care | 2 | 4% | 1 | 2% |

| Public administration (e.g., at federal, state, or local level) | 1 | 2% | 2 | 5% |

| Further area | 21 | 41% | 9 | 21% |

| Representation of interests of other service providers | 19 | 37% | 8 | 19% |

| Science | 2 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Advice center | 0 | 0% | 1 | 2% |

| Educational background | ||||

| Health Economics | 10 | 20% | 6 | 14% |

| Medicine | 9 | 18% | 9 | 21% |

| Health care and nursing | 5 | 10% | 4 | 9% |

| Pharmacy | 5 | 10% | 2 | 5% |

| Midwife | 4 | 8% | 3 | 7% |

| Social Sciences | 4 | 8% | 2 | 5% |

| Law | 2 | 4% | 2 | 5% |

| Psychology | 2 | 4% | 1 | 2% |

| Other care profession (e.g., logopedics, ergotherapy, physiotherapy) | 16 | 31% | 16 | 37% |

| Other educational background | 17 | 33% | 3 | 7% |

| Economics | 5 | 10% | 6 | 14% |

| Public Health | 4 | 8% | 1 | 2% |

| Health Sciences and Management | 2 | 4% | 1 | 2% |

| Other | 4 | 8% | 1 | 2% |

| Items * | Round | Distribution (in %) | Central Tendency | Consensus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Mean | SD | Median | Direction | Level | |||

| (1) Measurement of treatment outcomes and costs for every patient | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Data on outcomes tangible and important to patients | 1 | 54 | 36 | 7 | 3 | 1.59 | 0.75 | 1 | + | high |

| Outcome data collection indication-specific | 1 | 43 | 38 | 15 | 4 | 1.81 | 0.85 | 2 | + | high | |

| Outcome data collection standardized | 1 | 59 | 29 | 6 | 6 | 1.59 | 0.85 | 1 | + | high | |

| Outcome data collection integrated into daily care | 1 | 54 | 28 | 15 | 3 | 1.66 | 0.84 | 1 | + | high | |

| Outcome data collection with valid instruments | 1 | 57 | 38 | 3 | 1 | 1.49 | 0.63 | 1 | + | high | |

| Outcome data on short- and long-term effects of treatment course | 1 | 59 | 35 | 6 | 0 | 1.47 | 0.61 | 1 | + | high | |

| All providers publish outcome data | 1 | 40 | 31 | 19 | 10 | 2.00 | 1.01 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Patient-individual collection of financial resources expended | 2 | 31 | 42 | 15 | 12 | 2.08 | 0.97 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Evaluation of expended financial resources by clinical and administrative staff | 2 | 42 | 37 | 15 | 6 | 1.85 | 0.89 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Regular team meetings on outcome data | 1 | 71 | 26 | 3 | 0 | 1.32 | 0.53 | 1 | + | high | |

| Regular team meetings on expended resources | 1 | 44 | 29 | 19 | 7 | 1.90 | 0.96 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Feasibility | Data on outcomes tangible and important to patients | 1 | 33 | 43 | 19 | 4 | 1.94 | 0.84 | 2 | + | moderate |

| Outcome data collection indication-specific | 1 | 32 | 50 | 12 | 6 | 1.91 | 0.82 | 2 | + | high | |

| Outcome data collection standardized | 2 | 52 | 29 | 15 | 4 | 1.71 | 0.87 | 1 | + | high | |

| Outcome data collection integrated into daily care | 2 | 52 | 29 | 15 | 4 | 1.71 | 0.87 | 1 | + | high | |

| Outcome data collection with valid instruments | 2 | 52 | 40 | 6 | 2 | 1.58 | 0.70 | 1 | + | high | |

| Outcome data on short- and long-term effects of treatment course | 2 | 38 | 48 | 10 | 4 | 1.79 | 0.78 | 2 | + | high | |

| All providers publish outcome data | 2 | 37 | 31 | 27 | 6 | 2.02 | 0.94 | 2 | + | low | |

| Patient-individual collection of financial resources expended | 2 | 25 | 38 | 23 | 13 | 2.25 | 0.99 | 2 | + | low | |

| Evaluation of expended financial resources by clinical and administrative staff | 2 | 38 | 29 | 25 | 8 | 2.02 | 0.98 | 2 | + | low | |

| Regular team meetings on outcome data | 2 | 42 | 44 | 12 | 2 | 1.73 | 0.74 | 2 | + | high | |

| Regular team meetings on expended resources | 2 | 33 | 35 | 33 | 0 | 2.00 | 0.82 | 2 | + | low | |

| Characteristics of institution responsible for determination, collection and evaluation of treatment outcomes and costs | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Independent/neutral/free from conflicts of interest | 1 | 84 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 1.19 | 0.47 | 1 | + | high |

| Legitimate members | 1 | 40 | 35 | 18 | 7 | 1.93 | 0.94 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Legally defined tasks | 1 | 43 | 41 | 16 | 0 | 1.74 | 0.73 | 2 | + | high | |

| Equal representation (e.g., payers, service providers, patients) | 1 | 54 | 26 | 9 | 10 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1 | + | high | |

| Democratically elected | 2 | 33 | 25 | 27 | 15 | 2.25 | 1.08 | 2 | dissent | ||

| Interdisciplinary | 1 | 69 | 26 | 4 | 0 | 1.35 | 0.57 | 1 | + | high | |

| Scientific and methodological expertise | 1 | 59 | 38 | 3 | 0 | 1.44 | 0.56 | 1 | + | high | |

| Scientific-clinical expertise | 1 | 66 | 31 | 1 | 1 | 1.38 | 0.60 | 1 | + | high | |

| Feasibility | Independent/neutral/free from conflicts of interest | 2 | 52 | 29 | 19 | 0 | 1.67 | 0.79 | 1 | + | high |

| Legitimate members | 1 | 32 | 49 | 15 | 4 | 1.91 | 0.81 | 2 | + | high | |

| Legally defined tasks | 1 | 32 | 54 | 13 | 0 | 1.81 | 0.65 | 2 | + | high | |

| Equal representation (e.g., payers, service providers, patients) | 1 | 29 | 46 | 19 | 6 | 2.01 | 0.86 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Democratically elected | 2 | 25 | 35 | 27 | 13 | 2.29 | 1.00 | 2 | dissent | ||

| Interdisciplinary | 1 | 38 | 49 | 9 | 4 | 1.79 | 0.78 | 2 | + | high | |

| Scientific and methodological expertise | 1 | 40 | 49 | 12 | 0 | 1.72 | 0.67 | 2 | + | high | |

| Scientific-clinical expertise | 1 | 43 | 50 | 7 | 0 | 1.65 | 0.62 | 2 | + | high | |

| (2) Organization of care in integrated care facilities & networks | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Multidisciplinary treatment (outpatient, inpatient & rehabilitative services) | 1 | 80 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 1.22 | 0.45 | 1 | + | high |

| Indication-specific health care organization | 1 | 50 | 30 | 13 | 7 | 1.77 | 0.93 | 1.5 | + | high | |

| Health care as joint responsibility of multidisciplinary treatment team | 1 | 68 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 1.47 | 0.79 | 1 | + | high | |

| Health care planned from the outset | 1 | 58 | 35 | 3 | 3 | 1.52 | 0.72 | 1 | + | high | |

| Common management structure within a care network | 1 | 37 | 33 | 22 | 8 | 2.02 | 0.97 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Common scheduling system within a care network | 1 | 40 | 52 | 7 | 2 | 1.70 | 0.67 | 2 | + | high | |

| Joint cross-sector payment within a care network | 1 | 45 | 32 | 15 | 8 | 1.87 | 0.96 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Management by one team leader per patient within a care network | 1 | 35 | 37 | 22 | 7 | 2.00 | 0.92 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Health care for each indication at one location | 1 | 10 | 20 | 48 | 22 | 2.82 | 0.89 | 3 | - | moderate | |

| Feasibility | Multidisciplinary treatment (outpatient, inpatient & rehabilitative services) | 2 | 50 | 31 | 17 | 2 | 1.71 | 0.82 | 1.5 | + | high |

| Indication-specific health care organization | 2 | 44 | 42 | 13 | 2 | 1.73 | 0.76 | 2 | + | high | |

| Health care as joint responsibility of multidisciplinary treatment team | 2 | 44 | 31 | 21 | 4 | 1.85 | 0.90 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Health care planned from the outset | 2 | 44 | 44 | 10 | 2 | 1.71 | 0.74 | 2 | + | high | |

| Common management structure within a care network | 2 | 29 | 31 | 27 | 13 | 2.23 | 1.02 | 2 | + | low | |

| Common scheduling system within a care network | 2 | 40 | 42 | 10 | 8 | 1.88 | 0.91 | 2 | + | high | |

| Joint cross-sector payment within a care network | 2 | 38 | 19 | 31 | 13 | 2.19 | 1.08 | 2 | dissent | ||

| Management by one team leader per patient within a care network | 2 | 33 | 42 | 19 | 6 | 1.98 | 0.89 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Health care for each indication at one location | 2 | 15 | 29 | 44 | 13 | 2.54 | 0.90 | 3 | dissent | ||

| (3) Organization of integrated service provision between facilities | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Specific service offering of each care institution | 1 | 46 | 39 | 8 | 7 | 1.76 | 0.88 | 2 | + | high |

| Disease-specific interdisciplinary providers with high treatment volume for scheduled or complex treatments | 1 | 61 | 36 | 3 | 0 | 1.42 | 0.56 | 1 | + | high | |

| Routine care provision at less costly sites | 1 | 54 | 32 | 8 | 5 | 1.64 | 0.85 | 1 | + | high | |

| Coordinating institution for cooperation between care institutions | 2 | 26 | 60 | 11 | 4 | 1.94 | 0.73 | 2 | + | high | |

| Feasibility | Specific service offering of each care institution | 2 | 23 | 57 | 19 | 0 | 1.96 | 0.66 | 2 | + | high |

| Disease-specific interdisciplinary providers with high treatment volume for scheduled or complex treatments | 1 | 29 | 47 | 19 | 5 | 2.00 | 0.83 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Routine care provision at less costly sites | 2 | 49 | 45 | 6 | 0 | 1.57 | 0.62 | 2 | + | high | |

| Coordinating institution for cooperation between care institutions | 2 | 23 | 45 | 21 | 11 | 2.19 | 0.92 | 2 | + | low | |

| (4) Geographic expansion of excellent forms of care | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Expanding excellent forms of care rather than the catchment area | 1 | 29 | 55 | 13 | 4 | 1.91 | 0.75 | 2 | + | high |

| Cooperations in the form of care networks | 1 | 66 | 30 | 4 | 0 | 1.38 | 0.56 | 1 | + | high | |

| Care institutions responsible for expansion of collaboration | 2 | 30 | 34 | 30 | 6 | 2.13 | 0.92 | 2 | + | low | |

| Rotation of individual employees between participating care facilities | 1 | 39 | 38 | 18 | 5 | 1.89 | 0.89 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Feasibility | Expanding excellent forms of care rather than the catchment area | 2 | 21 | 45 | 30 | 4 | 2.17 | 0.82 | 2 | + | low |

| Cooperations in the form of care networks | 2 | 49 | 36 | 11 | 4 | 1.70 | 0.83 | 2 | + | high | |

| Care institutions responsible for expansion of collaboration | 2 | 26 | 28 | 38 | 9 | 2.30 | 0.95 | 2 | dissent | ||

| Rotation of individual employees between participating care facilities | 2 | 34 | 28 | 34 | 4 | 2.09 | 0.93 | 2 | + | low | |

| (5) Common remuneration of all treatment steps | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Inter-sectoral, risk-adjusted joint budget provided to a care network | 2 | 20 | 53 | 24 | 2 | 2.09 | 0.73 | 2 | + | moderate |

| Inter-sectoral joint budget for indications with multidisciplinary treatment needs | 2 | 31 | 44 | 22 | 2 | 1.96 | 0.80 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Annually adjusted inter-sectoral joint budget | 1 | 39 | 37 | 11 | 13 | 1.98 | 1.02 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Inter-sectoral joint budget based on treatment outcomes | 2 | 27 | 29 | 42 | 2 | 2.20 | 0.87 | 2 | dissent | ||

| No reimbursement of costs for preventable events | 2 | 13 | 40 | 36 | 11 | 2.44 | 0.87 | 2 | dissent | ||

| Additional reimbursement of costs for unavoidable events | 1 | 54 | 30 | 11 | 6 | 1.69 | 0.89 | 1 | + | high | |

| Feasibility | Inter-sectoral, risk-adjusted joint budget provided to a care network | 2 | 18 | 33 | 38 | 11 | 2.42 | 0.92 | 2 | dissent | |

| Inter-sectoral joint budget for indications with multidisciplinary treatment needs | 2 | 31 | 51 | 16 | 2 | 1.89 | 0.75 | 2 | + | high | |

| Annually adjusted inter-sectoral joint budget | 2 | 36 | 31 | 29 | 4 | 2.02 | 0.92 | 2 | + | low | |

| Inter-sectoral joint budget based on treatment outcomes | 1 | 7 | 20 | 41 | 31 | 2.96 | 0.91 | 3 | - | moderate | |

| No reimbursement of costs for preventable events | 2 | 18 | 33 | 33 | 16 | 2.47 | 0.97 | 2 | dissent | ||

| Additional reimbursement of costs for unavoidable events | 2 | 47 | 38 | 13 | 2 | 1.71 | 0.79 | 2 | + | high | |

| (6) Establishment of an information technology | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Digital patient record for each patient | 1 | 89 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 1.13 | 0.39 | 1 | + | high |

| Data relevant to care covers the entire course of treatment | 1 | 87 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 1.17 | 0.51 | 1 | + | high | |

| Standardized structure of digital patient record | 1 | 91 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 1.11 | 0.38 | 1 | + | high | |

| Digital patient record accessible to all providers involved in care | 1 | 83 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 1.21 | 0.49 | 1 | + | high | |

| Digital patient record as intelligent system with disease-specific recommendations | 1 | 64 | 25 | 8 | 4 | 1.51 | 0.80 | 1 | + | high | |

| Feasibility | Digital patient record for each patient | 1 | 40 | 34 | 26 | 0 | 1.87 | 0.81 | 2 | + | moderate |

| Data relevant to care covers the entire course of treatment | 2 | 59 | 25 | 14 | 2 | 1.59 | 0.82 | 1 | + | high | |

| Standardized structure of digital patient record | 1 | 38 | 36 | 21 | 6 | 1.94 | 0.91 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Digital patient record accessible to all providers involved in care | 1 | 38 | 36 | 25 | 2 | 1.91 | 0.84 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Digital patient record as intelligent system with disease-specific recommendations | 2 | 52 | 34 | 9 | 5 | 1.66 | 0.83 | 1 | + | high | |

| (7) Improve transparency | |||||||||||

| Relevance | Clear communication of responsibilities in macro-level decisions | 1 | 61 | 29 | 10 | 0 | 1.49 | 0.67 | 1 | + | high |

| Clear communication of decision criteria in macro-level decisions | 1 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 1.25 | 0.44 | 1 | + | high | |

| Clear communication of data bases in macro-level decisions | 1 | 71 | 24 | 6 | 0 | 1.35 | 0.59 | 1 | + | high | |

| Clear communication of decision-making bodies in macro-level decisions | 1 | 65 | 27 | 8 | 0 | 1.43 | 0.64 | 1 | + | high | |

| Clear communication of conflicts of interest in macro-level decisions | 1 | 69 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 1.35 | 0.56 | 1 | + | high | |

| Patient-comprehensible communication in micro-level decisions | 1 | 82 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 1.20 | 0.45 | 1 | + | high | |

| Presentation of different treatment options to patients in micro-level decisions | 1 | 73 | 25 | 2 | 0 | 1.29 | 0.50 | 1 | + | high | |

| Structured shared decision making in micro-level decisions | 1 | 76 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 1.27 | 0.53 | 1 | + | high | |

| Structured advice on self-management and health promotion in micro-level decisions | 1 | 75 | 20 | 6 | 0 | 1.31 | 0.58 | 1 | + | high | |

| Feasibility | Clear communication of responsibilities in macro-level decisions | 1 | 35 | 41 | 22 | 2 | 1.90 | 0.81 | 2 | + | moderate |

| Clear communication of decision criteria in macro-level decisions | 1 | 37 | 39 | 22 | 2 | 1.88 | 0.82 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Clear communication of data bases in macro-level decisions | 1 | 35 | 51 | 12 | 2 | 1.80 | 0.72 | 2 | + | high | |

| Clear communication of decision-making bodies in macro-level decisions | 1 | 45 | 41 | 12 | 2 | 1.71 | 0.76 | 2 | + | high | |

| Clear communication of conflicts of interest in macro-level decisions | 1 | 43 | 27 | 24 | 6 | 1.92 | 0.96 | 2 | + | moderate | |

| Patient-comprehensible communication in micro-level decisions | 1 | 47 | 43 | 10 | 0 | 1.63 | 0.66 | 2 | + | high | |

| Presentation of different treatment options to patients in micro-level decisions | 1 | 43 | 43 | 14 | 0 | 1.71 | 0.70 | 2 | + | high | |

| Structured shared decision making in micro-level decisions | 1 | 41 | 43 | 16 | 0 | 1.75 | 0.72 | 2 | + | high | |

| Structured advice on self-management and health promotion in micro-level decisions | 1 | 41 | 45 | 14 | 0 | 1.73 | 0.70 | 2 | + | high | |

| Relevance Rank * | Strategy | Item | Mean Relevance | Mean Feasibility | Feasibility Rank * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (6) Establishment of an information technology | Standardized structure of digital patient record | 1.11 | 1.94 | 36 |

| 2 | (6) Establishment of an information technology | Digital patient record for each patient | 1.13 | 1.87 | 26 |

| 3 | (6) Establishment of an information technology | Data relevant to care covers the entire course of treatment | 1.17 | 1.59 | 3 |

| 4 | (1) Measurement of treatment outcomes and costs for every patient | Characteristics of institution responsible for determination, collection and evaluation of treatment outcomes and costs: independent/neutral/free from conflicts of interest | 1.19 | 1.67 | 7 |

| 5 | (7) Improve transparency | Patient-comprehensible communication in micro-level decisions | 1.20 | 1.63 | 4 |

| 6 | (6) Establishment of an information technology | Digital patient record accessible to all providers involved in care | 1.21 | 1.91 | 31 |

| 7 | (2) Organization of care in integrated care facilities & networks | Multidisciplinary treatment (outpatient, inpatient & rehabilitative services) | 1.22 | 1.71 | 11 |

| 8 | (7) Improve transparency | Clear communication of decision criteria in macro-level decisions | 1.25 | 1.88 | 28 |

| 9 | (7) Improve transparency | Structured shared decision making in micro-level decisions | 1.27 | 1.75 | 20 |

| 10 | (7) Improve transparency | Presentation of different treatment options to patients in micro-level decisions | 1.29 | 1.71 | 10 |

| Feasibility Rank * | Strategy | Item | Mean Feasibility | Mean Relevance | Relevance Rank * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (3) Organization of integrated service provision between facilities | Routine care provision at less costly sites | 1.57 | 1.64 | 29 |

| 2 | (1) Measurement of treatment outcomes and costs for every patient | Outcome data collection with valid instruments | 1.58 | 1.49 | 23 |

| 3 | (6) Establishment of an information technology | Data relevant to care covers the entire course of treatment | 1.59 | 1.17 | 3 |

| 4 | (7) Improve transparency | Patient-comprehensible communication in micro-level decisions | 1.63 | 1.20 | 5 |

| 5 | (1) Measurement of treatment outcomes and costs for every patient | Characteristics of institution responsible for determination, collection and evaluation of treatment outcomes and costs: Scientific-clinical expertise | 1.65 | 1.38 | 17 |

| 6 | (6) Establishment of an information technology | Digital patient record as intelligent system with disease-specific recommendations | 1.66 | 1.51 | 25 |

| 7 | (1) Measurement of treatment outcomes and costs for every patient | Characteristics of institution responsible for determination, collection and evaluation of treatment outcomes and costs: independent/neutral/free from conflicts of interest | 1.67 | 1.19 | 4 |

| 8 | (4) Geographic expansion of excellent forms of care | Cooperations in the form of care networks | 1.70 | 1.38 | 16 |

| 9 | (7) Improve transparency | Clear communication of decision-making bodies in macro-level decisions | 1.71 | 1.43 | 19 |

| 10 | (7) Improve transparency | Presentation of different treatment options to patients in micro-level decisions | 1.71 | 1.29 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krebs, F.; Engel, S.; Vennedey, V.; Alayli, A.; Simic, D.; Pfaff, H.; Stock, S.; on behalf of the Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net). Transforming Health Care Delivery towards Value-Based Health Care in Germany: A Delphi Survey among Stakeholders. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081187

Krebs F, Engel S, Vennedey V, Alayli A, Simic D, Pfaff H, Stock S, on behalf of the Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net). Transforming Health Care Delivery towards Value-Based Health Care in Germany: A Delphi Survey among Stakeholders. Healthcare. 2023; 11(8):1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081187

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrebs, Franziska, Sabrina Engel, Vera Vennedey, Adrienne Alayli, Dusan Simic, Holger Pfaff, Stephanie Stock, and on behalf of the Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net). 2023. "Transforming Health Care Delivery towards Value-Based Health Care in Germany: A Delphi Survey among Stakeholders" Healthcare 11, no. 8: 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081187

APA StyleKrebs, F., Engel, S., Vennedey, V., Alayli, A., Simic, D., Pfaff, H., Stock, S., & on behalf of the Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net). (2023). Transforming Health Care Delivery towards Value-Based Health Care in Germany: A Delphi Survey among Stakeholders. Healthcare, 11(8), 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081187