Are Nurse Coordinators Really Performing Coordination Pathway Activities? A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies in Oncology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Field Selection

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

- 1.

- Coding observations for NC: Activity Unit (AU) definition

- 2.

- Individual analysis

- 3.

- Comparing data between NCs

2.4. Research Ethics

- Research based on surveys and interviews with health professionals but not on the health of said professionals (e.g., burnout, addictions, etc.). In these cases, professionals are considered patients;

- Research on teaching practices, particularly in health students, including simulations (as long as they do not involve the registration of any physiological parameters);

- Research based on human and social science methods.

3. Results

3.1. Role and Job Title Heterogeneity

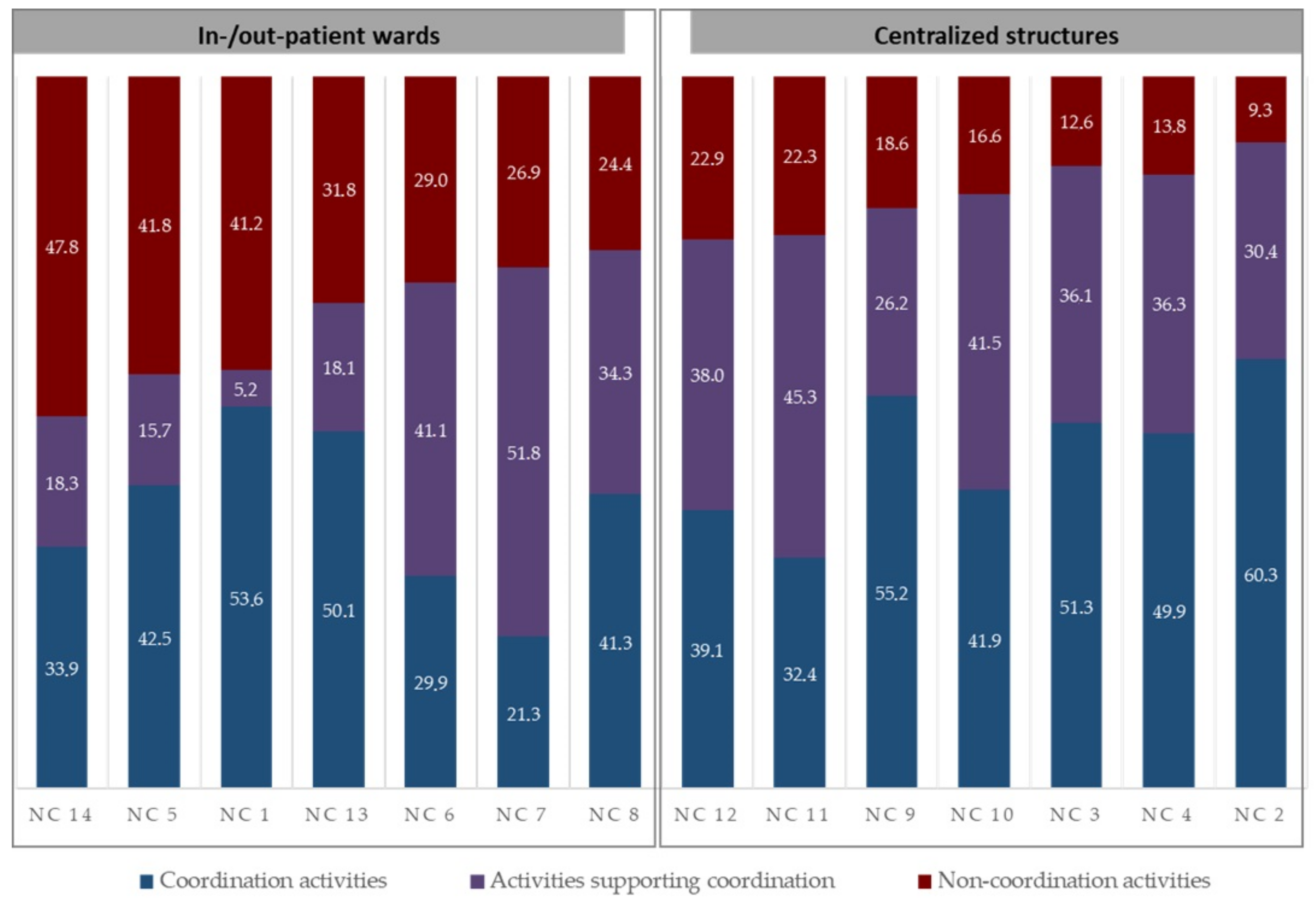

3.2. NC Non-Coordination Activities

3.3. Supporting Coordination Activities

3.3.1. Supporting NC Coordination Work

3.3.2. Supporting Physicians’ Coordination Work

3.4. PPC Activities: NCs in Inpatient and Outpatient Wards versus NCs in Centralized Structures

3.4.1. Centralized Structures Facilitate PPC Design or Patient Pathway Customization

3.4.2. Centralized Structures Facilitate External Coordination Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. NC Work Content: Time Dedicated to Coordination

4.2. Activity Differences According to NC Location

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bodenheimer, T. Coordinating Care—A Perilous Journey through the Health Care System. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1064–1071. Available online: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165 (accessed on 1 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Yatim, F.; Cristofalo, P.; Ferrua, M.; Girault, A.; Lacaze, M.; Di Palma, M.; Minvielle, E. Analysis of nurse navigators’ activities for hospital discharge coordination: A mixed method study for the case of cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, S.S.; Haggstrom, D.; Han, P.K.J.; Fairfield, K.M.; Krebs, P.; Clauser, S.B. Cancer Care Coordination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of over 30 Years of Empirical Studies. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 532–546. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/abm/article/51/4/532-546/4643218 (accessed on 21 June 2019). [CrossRef]

- Shrank, W.H.; Rogstad, T.L.; Parekh, N. Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings. JAMA 2019, 322, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, K.; Banfield, M.; McRae, I.; Gillespie, J.; Yen, L. Improving coordination through information continuity: A framework for translational research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 590. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-014-0590-5 (accessed on 13 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Levula, A.V.; Chung, K.S.K.; Young, J.; White, K. Envisioning complexity in healthcare systems through social networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining-ASONAM ’13, Niagara, ON, Canada, 25–28 August 2013; ACM Press: Niagara, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 931–936. Available online: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2492517.2500313 (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Lippi, G. Cancer statistics: A comparison between World Health Organization (WHO) and Global Burden of Disease (GBD). Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 1026–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Brown, R.; Archibald, N.; Aliotta, S.; Fox, P.D. Best Practices in Coordinated Care; Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Dohan, D.; Schrag, D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: Current practices and approaches. Cancer 2005, 104, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, H.P. The History, Principles, and Future of Patient Navigation: Commentary. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 29, 72–75. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0749208113000120 (accessed on 30 July 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellrodt, G.; Cook, D.J.; Lee, J.; Cho, M.; Hunt, D.; Weingarten, S. Evidence-Based Disease Management. JAMA 1997, 278, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baileys, K.; McMullen, L.; Lubejko, B.; Christensen, D.; Haylock, P.J.; Rose, T.; Sellers, J.; Srdanovic, D. Nurse Navigator Core Competencies: An Update to Reflect the Evolution of the Role. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 272–281. Available online: http://cjon.ons.org/cjon/22/3/nurse-navigator-core-competencies-update-reflect-evolution-role (accessed on 26 July 2019). [CrossRef]

- Wells, K.J.; Battaglia, T.A.; Dudley, D.J.; Garcia, R.; Greene, A.; Calhoun, E.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Paskett, E.D.; Raich, P.C.; The Patient Navigation Research Program. Patient navigation: State of the art or is it science? Cancer 2008, 113, 1999–2010. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2679696/ (accessed on 29 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Conway, A.; O’Donnell, C.; Yates, P. The Effectiveness of the Nurse Care Coordinator Role on Patient-Reported and Health Service Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Eval. Health Prof. 2019, 42, 263–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, L. Oncology Nurse Navigators and the Continuum of Cancer Care. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 29, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.; Hegney, D.; Harvey, C.; Baldwin, A.; Willis, E.; Heard, D.; Judd, J.; Palmer, J.; Brown, J.; Heritage, B.; et al. Exploring the nurse navigator role: A thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manderson, B.; Mcmurray, J.; Piraino, E.; Stolee, P. Navigation roles support chronically ill older adults through healthcare transitions: A systematic review of the literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.H.; Ludman, E.J.; Bowles, E.J.A.; Penfold, R.; Reid, R.J.; Rutter, C.M.; Chubak, J.; McCorkle, R. Nurse Navigators in Early Cancer Care: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 12–18. Available online: http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7359 (accessed on 21 June 2019). [CrossRef]

- Cantril, C.; Christensen, D.; Moore, E. Standardizing Roles: Evaluating Oncology Nurse Navigator Clarity, Educational Prep-aration, and Scope of Work Within Two Healthcare Systems. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 23, 52–59. Available online: https://cjon.ons.org/cjon/23/1/standardizing-roles-evaluating-oncology-nurse-navigator-clarity-educational-preparation (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Fillion, L.; Cook, S.; Veillette, A.M.; Aubin, M.; de Serres, M.; Rainville, F.; Fitch, M.; Doll, R. Professional Navigation Framework: Elaboration and Validation in a Canadian Context. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2012, 39, E58–E69. Available online: http://onf.ons.org/onf/39/1/professional-navigation-framework-elaboration-and-validation-canadian-context (accessed on 13 December 2019). [CrossRef]

- McMurray, A.; Cooper, H. The nurse navigator: An evolving model of care. Collegian 2017, 24, 205–212. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1322769616000032 (accessed on 30 July 2019). [CrossRef]

- Acero, M.-X.; Minvielle, E.; Waelli, M. Understanding the activity of oncology nurse coordinators: An elaboration of a framework based on an abductive approach. Health Policy 2023, 130, 104737. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168851023000404 (accessed on 17 February 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institut National du Cancer. Plan Cancer 2014–2019: Guérir et Prévenir les Cancers: Donnons les Mêmes Chances à Tous, Partout en France, FÉVRIER; Institut National du Cancer: France, Paris, 2014; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukas, H. The Validity of Idiographic Research Explanations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 551–561. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/258558 (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S. Studying actions in context: A qualitative shadowing method for organizational research. Qual. Res. 2005, 5, 455–473. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1468794105056923 (accessed on 6 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Lopetegui, M.; Yen, P.Y.; Lai, A.; Jeffries, J.; Embi, P.; Payne, P. Time motion studies in healthcare: What are we talking about? J. Biomed. Inform. 2014, 49, 292–299. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1532046414000562 (accessed on 15 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Toulouse, E.; Masseguin, C.; Lafont, B.; McGurk, G.; Harbonn, A.; Roberts, J.A.; Granier, S.; Dupeyron, A.; Bazin, J.E. French legal approach to clinical research. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2018, 37, 607–614. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352556818304466 (accessed on 9 December 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salma, I.; Waelli, M. Assessing the Integrative Framework for the Implementation of Change in Nursing Practice: Comparative Case Studies in French Hospitals. Healthcare 2022, 10, 417. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/10/3/417 (accessed on 9 December 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, D. Re-conceptualising holism in the contemporary nursing mandate: From individual to organisational relationships. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 119, 131–138. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953614005620 (accessed on 26 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Karam, M.; Brault, I.; Van Durme, T.; Macq, J. Comparing interprofessional and interorganizational collaboration in healthcare: A systematic review of the qualitative research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 79, 70–83. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0020748917302559 (accessed on 4 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Hannan-Jones, C.M.; Mitchell, G.K.; Mutch, A.J. The nurse navigator: Broker, boundary spanner and problem solver. Collegian 2021, 28, 622–627. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1322769621001190 (accessed on 1 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.; Herker, D. Boundary Spanning Roles and Organization Structure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1977, 2, 217–230. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/257905 (accessed on 25 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Allen, D. The nursing-medical boundary: A negotiated order? Sociol. Health Illn. 2008, 19, 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, L.; Waelli, M.; Allen, D.; Minvielle, E. The content and meaning of administrative work: A qualitative study of nursing practices. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2179–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, R.; McHale, H.; Palfrey, R.; Curtis, K. The trauma nurse coordinator in England: A survey of demographics, roles and resources. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2015, 23, 8–12. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1755599X14000482 (accessed on 31 July 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spooner, A.J.; Booth, N.; Downer, T.-R.; Gordon, L.; Hudson, A.P.; Bradford, N.K.; O’Donnell, C.; Geary, A.; Henderson, R.; Franks, C.; et al. Advanced practice profiles and work activities of nurse navigators: An early-stage evaluation. Collegian 2019, 26, 103–109. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1322769618300489 (accessed on 1 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Valaitis, R.K.; Carter, N.; Lam, A.; Nicholl, J.; Feather, J.; Cleghorn, L. Implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs linking primary care with community-based health and social services: A scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 116. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5294695/ (accessed on 9 May 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Not-Profit Hospital (HCO-1) | Public Academic Oncology Center (HCO-2) | Public Teaching Hospital (HCO-3) | Not-Profit Research Institute and International Cancer Center (HCO-4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information | |||||||

| Beds | 140 | 59 | 898 | 365 | |||

| Day-patient capacity | 26 | 49 | 147 | 94 | |||

| Care days In-P † | 8425 | 1843 | 120,667 | 19,807 | |||

| Care days DH ‡ | 6693 | 1753 | - | 7221 | |||

| Average length of stay | 5.2 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 6.7 | |||

| Link to | Inpatient ward | Centralized structure | In- and Out- patient ward | Inpatient ward | Centralized structure | Centralized structure | Inpatient ward |

| Hierarchical chain | Gynecology ward nurse manager | Centralized Structure nurse manager | Ward nurse manager | Ward nurse manager | Centralized Structure nurse manager | Ward nurse manager | |

| Cancer type | Breast cancer only | All types | All cancer types except hematology | All cancer types in the elderly. Respiratory system only | Patients on oral therapy | All types | All types |

| Formalized since Role design | Not yet formalized | 2010 | 2017 | 2013 | 2015 | 2008 | 2016 |

| Professional (between the NC and the surgeon) | Institutional | Institutional | Professional design, which was institutionalized | Institutional | |||

| Human resources | 1 Coordination Support Nurse 3 Nurses Secretaries | 5 Nurse Pivots 1 Pivot technical radiology assistant 1 Secretary 1 Advanced Practice Nurse | 2 Liaison nurses 2 Nurse coordinators 2 Secretaries | 2 Nurse coordinators 2 Scheduling nurses 2 Secretaries | 2 Nurse coordinators 1 Research assistant 1 Secretary | 5 Nurse coordinators 1 secretary 1 nurse’s aide | 1 Nurse coordinator by ward 2 Secretaries |

| Other resources |

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Funding | HCO | Government funding Associative funding HCO | Government funding | Government funding/HCO | HCO | HCO | |

| Study NCs | NC1: Coordination Support Nurse | NC2: Pivot Nurse NC3: Pivot Nurse NC4: Pivot Nurse | NC5: Liaison nurse H † NC6: Nurse coordinator DH ‡ | NC7: Nurse geriatric coordinator NC8: Nurse pneumology coordinator | NC9: Nurse coordinator NC10: Nurse coordinator | NC11: Nurse coordinator NC12: Nurse coordinator | NC13: Nurse medicine coordinator NC14: Nurse surgical coordinator |

| Categories | Definitions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | Coordination activity | PPC is a collective activity between NCs, other professionals (medical, paramedical, or social), and cancer patients or their families. This collective activity involved sharing patient-related information (e.g., clinical, psychosocial, and service information) between pathway actors, regardless of their location (ambulatory/hospital), to ensure a smooth and continuous pathway. | ||

| Sub- Categories | 1.1 | Design coordination activity | coordination conducted during the development and updating of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies | |

| Implementation coordination activity | activities related to the diagnostic and therapeutic strategy, which depends on understanding work situations and defining corrective actions | |||

| 1.2 | Internal coordination activity | coordination activities facilitating inpatient care | ||

| External coordination activity | coordination activities ensuring continuity and smooth transitions between the hospital and primary care or outpatient care | |||

| 1.3 | Coordination activity between NCs and patients (families) | coordination activities with patients, face-to-face or by telephone, or applications | ||

| Coordination activity between professionals and NCs | coordination activity is conducted with healthcare professionals involved in the patient pathway, in person, by telephone, or through applications | |||

| 1.4 | Formal coordination activity | coordination between professionals through standardized procedures | ||

| Informal coordination activity | coordination between professionals through informal coordination mechanisms | |||

| Category 2 | Activities supporting coordination | these activities do not directly influence patient pathway fluidity but are required for the smooth running of coordination actions. We categorized them into three types: | ||

| Sub- Categories | 2.1 | Supporting NC coordination | activities supporting NC coordination activities | |

| 2.2 | Supporting other coordination | activities supporting the coordination activities of other professionals | ||

| 2.3 | Relational coordination | activities that promoted links and good understanding between the coordinator and other professionals | ||

| Category 3 | Non-coordination activities | actions that do not coordinate the patient pathway. E.g., | ||

| Clinical activity, time visiting patients, training/expertise, ward management, and journey planning | ||||

| Inpatient and Outpatient Wards | Centralized Structures | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCO4 | HCO2 | HCO1 | HCO4 | HCO2 | HCO3 | HCO3 | HCO4 | HCO4 | HCO4 | HCO4 | HCO2 | HCO2 | HCO2 | ||

| NC14 (%) * | NC5 (%) | NC1 (%) | NC13 (%) | NC6 (%) | NC7 (%) | NC8 (%) | NC12 (%) | NC11 (%) | NC9 (%) | NC10 (%) | NC3 (%) | NC4 (%) | NC2 (%) | ||

| Category 1. Coordination | 33.9 | 42.5 | 53.6 | 50.1 | 29.9 | 21.3 | 41.3 | 39.1 | 32.4 | 55.2 | 41.9 | 51.3 | 49.9 | 60.3 | |

| 1.1 | Design/ | 0.40 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 10.3 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 20.5 | 15.4 | 20.1 |

| Implementation | 33.6 | 41.6 | 53.6 | 48.6 | 29.9 | 14.8 | 30.9 | 36.1 | 28.6 | 47.3 | 33.3 | 30.8 | 34.6 | 40.2 | |

| 1.2 | Internal/ | 30.0 | 28.4 | 35.5 | 38.8 | 24.0 | 16.7 | 26.7 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 14.0 | 11.9 | 39.7 | 38.4 | 37.4 |

| External | 4.0 | 14.1 | 18.1 | 11.4 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 14.5 | 36.7 | 27.8 | 41.2 | 30.0 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 22.9 | |

| 1.3 | Professional/ | 33.6 | 38.4 | 5.1 | 40.8 | 23.6 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 21.4 | 18.1 | 16.9 | 15.2 | 18.7 | 17.4 | 25.3 |

| Patient | 0.4 | 4.2 | 48.4 | 9.3 | 6.3 | 12.4 | 29.9 | 17.6 | 14.2 | 38.3 | 26.6 | 32.6 | 32.5 | 35.0 | |

| 1.4 | Formal/ | 15.2 | 12.1 | 0.0 | 15.2 | 11.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 10.7 | 3.4 |

| Informal | 18.4 | 26.3 | 5.1 | 25.6 | 12.3 | 8.5 | 11.2 | 21.4 | 18.0 | 16.4 | 12.5 | 14.2 | 6.7 | 22.0 | |

| Category 2. Supporting coordination | 18.3 | 15.7 | 5.2 | 18.1 | 41.1 | 51.8 | 34.3 | 38.0 | 45.3 | 26.2 | 41.5 | 36.1 | 36.3 | 30.4 | |

| 2.1 | Supporting NC coordination | 8.3 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 13.4 | 16.8 | 10.0 | 10.4 | 15.9 | 13.6 | 21.7 | 28.0 | 28.2 | 28.7 | 19.5 |

| 2.2 | Supporting other coordination | 5.6 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 17.7 | 37.7 | 18.8 | 17.0 | 23.6 | 1.6 | 9.7 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 5.3 |

| 2.3 | Relational coordination | 4.4 | 9.6 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 6.5 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 8.2 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 5.6 |

| Category 3. Non-coordination | 47.8 | 41.8 | 41.2 | 31.8 | 29.0 | 26.9 | 24.4 | 22.9 | 22.3 | 18.6 | 16.6 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 9.3 | |

| Clinical activity | 11.4 | 10.1 | 20.8 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Time spent visiting patients | 0.1 | 1.6 | 6.7 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 5.7 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 8.1 | |

| Training/Expertise | 0.0 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 17.4 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.7 | 13.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| Ward management | 26.9 | 20.4 | 5.6 | 12.9 | 25.5 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Journey planning | 2.1 | 0.3 | 5.6 | 8.0 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.7 | 0.0 | |

| Institutional requests | 7.3 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 7.7 | 5.0 | 15.7 | 15.5 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 1.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acero, M.-X.; Minvielle, E.; Waelli, M. Are Nurse Coordinators Really Performing Coordination Pathway Activities? A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies in Oncology. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081090

Acero M-X, Minvielle E, Waelli M. Are Nurse Coordinators Really Performing Coordination Pathway Activities? A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies in Oncology. Healthcare. 2023; 11(8):1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081090

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcero, Maria-Ximena, Etienne Minvielle, and Mathias Waelli. 2023. "Are Nurse Coordinators Really Performing Coordination Pathway Activities? A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies in Oncology" Healthcare 11, no. 8: 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081090

APA StyleAcero, M.-X., Minvielle, E., & Waelli, M. (2023). Are Nurse Coordinators Really Performing Coordination Pathway Activities? A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies in Oncology. Healthcare, 11(8), 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081090