Appraisal and Evaluation of the Learning Environment Instruments of the Student Nurse: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology

Abstract

1. Introduction

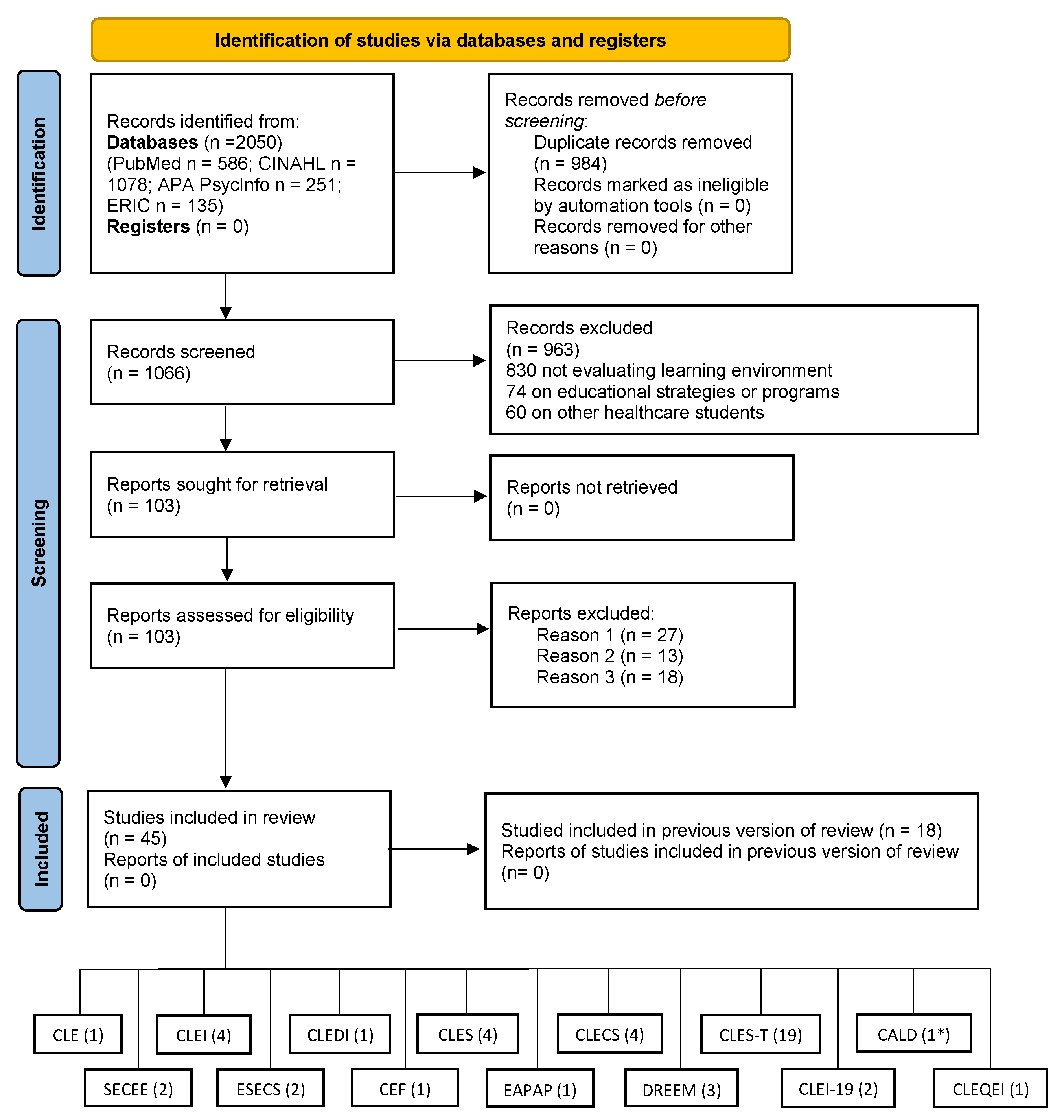

2. Methods

2.1. Methodology and Search Strategy

2.2. Data Synthesis and Quality Assessment Tool

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Studies Included in the Review

3.2. Methodological Quality, Overall Rating, and GRADE Quality of Evidence

3.3. Psychometric Properties, Overall Rating, and GRADE Quality of the Evidence

3.4. Learning Environment Instruments

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

|

|

|

References

- Lizzio, A.; Wilson, K.; Simons, R. University Students’ Perceptions of the Learning Environment and Academic Outcomes: Implications for Theory and Practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2002, 27, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letizia, M.; Jennrich, J. A review of preceptorship in undergraduate nursing education: Implications for staff development. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 1998, 29, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, H. Climate studies: Can students’ perceptions of the ideal educational environment be of use for institutional planning and resource utilization? Med. Teach. 2005, 27, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roff, S. The Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM)—A generic instrument for measuring students’ perceptions of undergraduate health professions curricula. Med. Teach. 2005, 27, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazimi, A.; Zaini, R.; Al-Hyiani, A.; Hassan, N.; Gunaid, A.; Ponnamperuma, G.; Karunathilake, I.; Roff, S.; McAleer, S.; Davis, M. Educational environment in traditional and innovative medical schools: A study in four undergraduate medical schools. Educ. Health 2004, 17, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimparyon, P.; Roff, S.; McAleer, S.; Poonchai, B.; Pemba, S. Educational environment, student approaches to learning and academic achievement in a Thai nursing school. Med. Teach. 2000, 22, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roff, S.; McAleer, S.; Ifere, O.S.; Bhattacharya, S. A global diagnostic tool for measuring educational environment: Comparing Nigeria and Nepal. Med. Teach. 2001, 23, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkan, B.; Ordin, Y.; Yılmaz, D. Undergraduate nursing students’ experience related to their clinical learning environment and factors affecting to their clinical learning process. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 29, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fego, M.W.; Olani, A.; Tesfaye, T. Nursing students’ perception towards educational environment in governmental Universities of Southwest Ethiopia: A qualitative study. PloS ONE 2022, 17, e0263169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, F.; Faris, E.A.; Maflehi, N.A.; Karim, S.I.; Ponnamperuma, G.; Saad, H.; Ahmed, A. The learning environment of four undergraduate health professional schools: Lessons learned. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhurtun, H.D.; Azimirad, M.; Saaranen, T.; Turunen, H. Stress and Coping Among Nursing Students During Clinical Training: An Integrative Review. J. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 58, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghamolaei, T.; Shirazi, M.; Dadgaran, I.; Shahsavari, H.; Ghanbarnejad, A. Health students’ expectations of the ideal educational environment: A qualitative research. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 2014, 2, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burrai, F.; Cenerelli, D.; Sebastiani, S.; Arcoleo, F. Analisi di affidabilità ed esplorazione fattoriale del questionario Clinical Learning Enviroment of Supervision (CLES). Scenario 2012, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hooven, K. Evaluation of instruments developed to measure the clinical learning environment: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. 2014, 39, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansutti, I.; Saiani, L.; Grassetti, L.; Palese, A. Instruments evaluating the quality of the clinical learning environment in nursing education: A systematic review of psychometric properties. Int. J. Nurs Stud. 2017, 68, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. Int J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. Int J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Jansma, E.P.; Riphagen, I.I.; de Vet, H.C.W. Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual. Life Res. Int J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2009, 18, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R. EndNote®. 2020. Available online: www.endnote.com (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Chang, Y.C.; Chang, H.Y.; Feng, J.Y. Appraisal and evaluation of the instruments measuring the nursing work environment: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkonen, K.; Elo, S.; Miettunen, J.; Saarikoski, M.; Kääriäinen, M. Development and testing of the CALDs and CLES+T scales for international nursing students’ clinical learning environments. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1997–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, J.; Al-Motlaq, M.; Hutchinson, C.; Sellick, K.; Burns, V.; James, A. Development of an undergraduate nursing Clinical Evaluation Form (CEF). Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, e58–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.V.; Burnett, P. The development of a clinical learning environment scale. J. Adv. Nurs. 1995, 22, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, K. Development of the Clinical Learning Environment Comparison Survey. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2015, 11, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.H.; Xiong, L.; Bai, J.B.; Hu, J.; Tan, X.D. Chinese version of the clinical learning environment comparison survey: Assessment of reliability and validity. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 71, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaussen, C.; Jelsness-Jørgensen, L.P.; Tvedt, C.R.; Hofoss, D.; Aase, I.; Steindal, S.A. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the clinical learning environment comparison survey. Nurs. Open. 2021, 8, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, S.; Abolfazlie, M.; Arabi, M. Psychometric Properties of Clinical Learning Environment Comparison Survey Questionnaire in Nursing Students. J. Adv. Med. Educ Prof. 2022, 10, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda, Y. Development and testing of a Clinical Learning Environment Diagnostic Inventory for baccalaureate nursing students. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. Development of an innovative tool to assess hospital learning environments. Nurse Educ. Today 2001, 21, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.S. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in assessing hospital learning environments. Int J. Nurs. Stud. 2001, 38, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D. Development of the Clinical Learning Environment Inventory: Using the theoretical framework of learning environment studies to assess nursing students’ perceptions of the hospital as a learning environment. J. Nurs. Educ. 2002, 41, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.M.; Jolly, B.C.; Ockerby, C.M.; Cross, W.M. Clinical learning environment inventory: Factor analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamonson, Y.; Bourgeois, S.; Everett, B.; Weaver, R.; Peters, K.; Jackson, D. Psychometric testing of the abbreviated Clinical Learning Environment Inventory (CLEI-19). J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 2668–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, M.; Maria, M.D.; Alberio, M.; Colombo, N.T.; Ongaro, C.; Sala, M.; Luciani, M.; Ausili, D.; Di Mauro, S. Proprietà psicometriche della scala CLEI-19 nella valutazione dell’apprendimento clinico degli studenti infermieri: Studio osservazionale multicentrico. Prof. Inferm. 2022, 2, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Palese, A.; Grassetti, L.; Mansutti, I.; Destrebecq, A.; Terzoni, S.; Altini, P.; Bevilacqua, A.; Brugnolli, A.; Benaglio, C.; Ponte, A.D.; et al. The Italian instrument evaluating the nursing students clinical learning quality. Assist. Inferm. Ric. AIR 2017, 36, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Saarikoski, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H. The clinical learning environment and supervision by staff nurses: Developing the instrument. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomietto, M.; Saiani, L.; Saarikoski, M.; Fabris, S.; Cunico, L.; Campagna, V.; Palese, A. Assessing quality in clinical educational setting: Italian validation of the clinical learning environment and supervision (CLES) scale. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2009, 31 (Suppl. 3), B49–B55. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, N.; Labeau, S.; De Keyzer, W. The clinical learning environment and supervision instrument (CLES): Validity and reliability of the Dutch version (CLES+NL). Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski, M.; Isoaho, H.; Warne, T.; Leino-Kilpi, H. The nurse teacher in clinical practice: Developing the new sub-dimension to the Clinical Learning Environment and Supervision (CLES) Scale. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1233–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, U.B.; Kaila, P.; Ahlner-Elmqvist, M.; Leksell, J.; Isoaho, H.; Saarikoski, M. Clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher evaluation scale: Psychometric evaluation of the Swedish version. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2085–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, N.; Normann, H.K.; Skaalvik, M.W. Development and testing of the Norwegian version of the Clinical Learning Environment, Supervision and Nurse Teacher (CLES+T) evaluation scale. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomietto, M.; Saiani, L.; Palese, A.; Cunico, L.; Cicolini, G.; Watson, P.; Saarikoski, M. Clinical learning environment and supervision plus nurse teacher (CLES+T) scale: Testing the psychometric characteristics of the Italian version. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2012, 34 (Suppl. 2), B72–B80. [Google Scholar]

- Bergjan, M.; Hertel, F. Evaluating students’ perception of their clinical placements—Testing the clinical learning environment and supervision and nurse teacher scale (CLES + T scale) in Germany. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.B.; Seaton, P.; Sims, D.; Jamieson, I.; Mountier, J.; Whittle, R.; Saarikoski, M. Exploratory factor analysis of the Clinical Learning Environment, Supervision and Nurse Teacher Scale (CLES+T). J. Nurs. Meas. 2014, 22, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizcaya-Moreno, M.F.; Pérez-Cañaveras, R.M.; De Juan, J.; Saarikoski, M. Development and psychometric testing of the Clinical Learning Environment, Supervision and Nurse Teacher evaluation scale (CLES+T): The Spanish version. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastavrou, E.; Dimitriadou, M.; Tsangari, H.; Andreou, C. Nursing students’ satisfaction of the clinical learning environment: A research study. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, B.; Taketomi, K.; Ito, Y.M.; Kohanawa, M.; Kawabata, H.; Tanaka, M.; Otaki, J. Nepalese undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of the clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teachers: A questionnaire survey. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovrić, R.; Piškorjanac, S.; Pekić, V.; Vujanić, J.; Ratković, K.K.; Luketić, S.; Plužarić, J.; Matijašić-Bodalec, D.; Barać, I.; Žvanut, B. Translation and validation of the clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher scale (CLES+T) in Croatian language. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 19, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyigun, E.; Tastan, S.; Ayhan, H.; Pazar, B.; Tekin, Y.E.; Coskun, H.; Saarikoski, M. The Clinical Learning Environment, Supervision and the Nurse Teacher Evaluation Scale: Turkish Version. Int. J. Nurs Pract. 2020, 26, e12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, S.; Kurt, F.Y.; Aslan, G.K.; Saarikoski, M.; Yılmaz, H.; Ekinci, V. Validity and reliability of the Clinical Learning Environment, Supervision and Nurse Teacher (CLES+T), Turkish version1. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2018, 26, e3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žvanut, B.; Lovrić, R.; Kolnik, T.Š.; Šavle, M.; Pucer, P. A Slovenian version of the «clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher scale (Cles+T)» and its comparison with the Croatian version. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 30, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, G.; Mylonas, D.; Schumacher, P. Quality assurance of the clinical learning environment in Austria: Construct validity of the Clinical Learning Environment, Supervision and Nurse Teacher Scale (CLES+T scale). Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 66, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.K.; Bressington, D.T. Psychometric properties of the clinical learning environment, Supervision and Nurse Teacher scale (CLES+T) for undergraduate nursing students in Hong Kong. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 52, 103007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Xiao, L.; Watson, R.; Chen, Y. Clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher scale (CLES+T): Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 106, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozbicakci, S.; Yesiltepe, A. The Cles+T Scale in Primary Health Care Settings: Methodological Study. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 15, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Guejdad, K.; Ikrou, A.; Strandell-Laine, C.; Abouqal, R.; Belayachi, J. Clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher (CLES+T) scale: Translation and validation of the Arabic version. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 63, 103374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zang, S.; Shan, T. Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure: Psychometric testing with Chinese nursing students. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 2701–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotthoff, T.; Ostapczuk, M.S.; De Bruin, J.; Decking, U.; Schneider, M.; Ritz-Timme, S. Assessing the learning environment of a faculty: Psychometric validation of the German version of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure with students and teachers. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, e624–e636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosak, L.; Fijačko, N.; Chabrera, C.; Cabrera, E.; Štiglic, G. Perception of the Online Learning Environment of Nursing Students in Slovenia: Validation of the DREEM Questionnaire. Healthcare 2021, 9, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Marín, J.; Hernández-Franco, V.; Plumed-Moreno, C. Nursing students’ perception of academic support in the practicum: Development of a reliable and valid measurement instrument. J. Prof. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Coll. Nurs. 2017, 33, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, R.C.N.; Martins, J.C.A.; Pereira, M.F.C.R.; Mazzo, A. Students’ satisfaction with simulated clinical experiences: Validation of an assessment scale. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2014, 22, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montejano-Lozoya, R.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Miguel-Montoya, I.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Sanjuán-Quiles, Á.; Ferrer-Ferrandiz, E. Validación de un cuestionario de satisfacción sobre la formación práctica de estudiantes de Enfermería. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 2019, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sand-Jecklin, K.E. Student Evaluation of Clinical Education Environment (SECEE): Instrument Development and Validation; West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Govina, O.; Vlachou, E.; Lavdaniti, M.; Kalemikerakis, I.; Margari, N.; Galanos, A.; Kavga, A. Psychometric Testing of the Student Evaluation of Clinical Educational Environment Inventory in Greek Nursing Students. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2017, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, H.D. Ward learning climate and student nurse response. Nurs. Times 1981, 77, (Suppl. 17), 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Roff, S.; McAleer, S.; Harden, R.M.; Al-Qahtani, M.; Ahmed, A.U.; Deza, H.; Groenen, G.; Primparyon, P. Development and validation of the Dundee ready education environment measure (DREEM). Med. Teach. 1997, 19, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand-Jecklin, K. Assessing nursing student perceptions of the clinical learning environment: Refinement and testing of the SECEE inventory. J. Nurs. Meas. 2009, 17, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B.J.; Fisher, D.L. Assessment of Classroom Psychosocial Environment. Workshop Manual. 1983. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED228296 (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. A perspective on changing dynamics in nursing over the past 20 years. Br. J. Nurs. 2010, 19, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tools | Author/ Year Publication/Country/Type of Study/Concept Evaluated | Sample | No.of Items/Subscale/Response System | Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Other Psychometric Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CALD | Mikkonen et al., 2017 [22] Finland Development study Clinical learning environment | 329 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 21 items 4 Subscales: orientation into clinical placement, role of student, cultural diversity in the clinical learning environment, and linguistic diversity in the clinical learning environment 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, 5 factors solution, 68% variance explained Content validity, a panel of 12 experts, CVI 0.75–1.00 Face validity, 10 nurse students | Total 0.88 Subscale: 0.77–0.85 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Hypothesis testing (convergent validity: CALD vs CLES-T): positive correlation between factor 1 CLES-T and Factor 3 CALD r = 0.62 p <0.01; positive correlation between Factor 2 CLES-T and Factor 4 CALD, r = 0.64 p < 0.01 |

| CEF | Porter et al., 2011 [23] Australia Development study Clinical placement environment | 178 nursing students in 1st and 2nd-year courses | 21 items 5 subscales: orientation, clinical educator/teacher, ward staff/preceptor and ward environment, final assessment/clinical hurdles, and university 5-point Likert (from 1 “never” to 5 “always”) | Content and face validity, a panel of 3 experts (relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility) Face validity, 6 nurse students (comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) | Total 0.90 Subscales 0.73–0.91 | |

| CLE | Dunn and Burnett, 1995 [24] Australia Development study Clinical Learning Environment | 340 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 23 items 5 subscales: staff-student relationship, nurse management commitment, patient relationship, interpersonal relationship, and student satisfaction 5-point Likert (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”) | PCA, orthogonal rotation, 4-factor solution, 34.6% explained variance CFA (testing scale with Orton’s theory): 5-factor solution GFI 0.86 AGFI 0.82 RMSR 0.07 Content validity (panel 12 members) | Subscales 0.60–0.83 (PCA) Subscales 0.63–0.85 (CFA) | |

| CLECS | Leighton, 2015 [25] USA Development study Clinical and simulated environment | 422 nursing students from 4 colleges | 27 items 6 subscales: communication, nursing process, holism, critical thinking, self-efficacy, and teaching-learning dyad 4-point Likert (from 1 “not meet” to 4 “well met”) | PCA, varimax rotation, 6 factors solution, 69.97% variance explained CFA, 6-factor solution (items 11 and 20 deleted), no index fit indicated | Total 0.94 Subscales 0.57–0.89 (traditional clinical environment) Total 0.90 Subscales 0.44–0.94 (simulated clinical environment) | Test-retest (recall period 2 week); r = 0.55, p < 0.05 (traditional environment); r = 0.58, p < 0.05 (simulated environment) |

| CLECS | Gu et al., 2018 [26] China Validation study Clinical and simulated environment | 179 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 27 items 6 subscales: communication, nursing process, holism, critical thinking, self-efficacy, and teaching-learning dyad 5-point Likert (from 0 “not meet” to 4 “well met”) | PCA, varimax rotation, 5 factors solution, 61.43% variance explained (traditional environment) and 4-factor solution, 60.11% variance explained (simulated environment) CFA, 7-factor solution CFI 0.93 GFI 0.83 RMSEA 0.06 (traditional and simulated) Content validity, a panel of 4 experts Face validity, 10 student nurses | Total 0.75 Subscales 0.59–0.90 (traditional clinical environment) Total 0.95 Subscales 0.65–0.92 (simulated clinical environment) | Cross-cultural Validity (Forward-backward translation) Reliability: ICC: 0.63 consistency and 0.61 concordances (traditional clinical environment); and 0.93 consistency and 0.93 concordances (simulated clinical environment) Test-retest (recall period 2 weeks), r = 0.50 in a simulated and traditional environment |

| CLECS | Olaussen et al., 2020 [27] Norway Validation study Clinical and simulated environment | 122 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 27 items of Simulated form the CLECS 6 subscales: communication, nursing process, holism, critical thinking, self-efficacy, and teaching-learning dyad 4-point Likert (from 1 “not applicable” to 4 “well met”) | CFA, 6-factor solution CFI 0.915 RMSEA 0.058 Content validity, a panel of 8 experts Face validity, 9 student nurses | Subscales 0.69–0.89 | Cross-cultural Validity (guideline WHO 2018) Reliability: ICC: >0.50 (from 0.55 to 0.75) |

| CLECS | Riahi et al., 2022 [28] Iran Validation study Clinical and simulated environment | 118 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 27 items of traditional form the CLECS 6 subscales: communication, nursing process, holism, critical thinking, self-efficacy, and teaching-learning dyad 5-point Likert (from 1 “not applicable” to 5 “well met”) | CFA, 6-factor solution CFI 0.829 RMSEA 0.078 | Total 0.94 Subscales 0.82–0.94 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Hypotheses testing for construct validity (convergent validity) between the score of each item and the total score (from 0.809 to 0.976; p < 0.05) Hypotheses testing for construct validity (discriminant validity) between the score of each item and dimension (no good) |

| CLEDI | Hosoda Y., 2006 [29] Japan Development study Clinical learning environment | 312 nursing students | 21 items 5 factors: affective CLE, perceptual CLE, symbolic CLE, behavioral CLE, and reflective CLE 5-point Likert scale (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”) | PCA, promax rotation, 5 factors solution, 52.45% variance explained Content validity, a panel of 22 experts (relevance, CVI) | Total 0.84 Subscales 0.65–0.77 | Test-retest r = 0.76, p <0.01 Criterion validity (CLEDI and CLES), r = 0.76, p < 0.01 Hypotheses testing (known-groups technique: students and preceptors), p < 0.001 |

| CLEI | Chan, 2001 [30], 2001 [31], 2002 [32]* Australia Development studies Clinical learning environment | 108 nursing students in a 2nd-year course (quantitative phase) 21 nursing students (qualitative phase in Chan, 2001 [30]) | Two forms: Actual CLEI and Preferred CLEI 35 items 5 subscales: individualization, innovation, involvement personalization, and task orientation 4-point Likert (from 1 “strongly agree” to 4 “strongly disagree”) | Subscales Actual form 0.73- 0.84 Subscales Preferred form 0.66- 0.80 | Hypotheses testing (convergent validity): Actual forms with Preferred Form (r = 0.39−0.47) | |

| CLEI | Newton et al., 2010 [33] Australia Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 513 nursing students in 2nd and 3rd-year courses | Actual CLEI form 42 items 6 subscales: personalization, student involvement, task orientation, innovation, satisfaction, and individualization 4-point Likert (from 1 “strongly agree” to 4 “strongly disagree”) | PCA, varimax rotation, 6 factors solution, 51% variance explained | Subscales 0.50–0.88 | |

| CLEI-19 | Salamonson et al., 2011 [34] Australia Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 231 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 19 items 2 subscales: clinical facilitator support of learning and satisfaction with clinical placement 5-point Likert (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree) | PCA, varimax rotation, 2-factor solution, 63.37% variance explained | Total 0.93 Subscales 0.92–0.94 | Hypotheses testing (known-groups technique: work and non-working students) no-working students and clinical facilitator r = 0.037, p < 0.05; work students and satisfaction clinical placement, r = 0.038, p < 0.05 |

| CLEI-19 | Leone et al., 2022 [35] Italy Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 1095 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 19 items 2 subscales: clinical facilitator support of learning and satisfaction with clinical placement 5-point Likert (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree) | ESEM, 2-factor solution CFI 0.963 TLI 0.953 RMSEA 0.069 SRMR 0.037 | Total 0–90 (alpha) Subscale 0.85–0.86 (Alpha) Total score 0.93 (Omega) Subscale 0.84- 0.89 (Omega) | |

| CLEQEI | Palese A. et al., 2017 [36] Italy Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 9606 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 22 items 5 subscales: quality of tutorial strategies, learning opportunities, safety and quality of care, self-learning, and quality of the learning environment 4-point Likert (from 0 “nothing” to 3 “very much” | EFA, 5-factor solution, 57,9% variance explained CFA, 5-factor solution CFI 0.966 TLI 0.960 RMSEA 0.050 SRMR 0.028 Content and face validity (experts and students) | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.82–0.93 | Reliability: ICC (0.866 consistency and 0.864 concordance) Hyphothesis testing (discriminant validity) with CLES (r = 0.248, p < 0.0001) CLES-T (r = 0.733, p < 0.0001) Test-retest (recall period 2 weeks) 49.24 and 49.88 |

| CLES | Saarikoski and Leino-Kilpi, 2002 [37] Finland Development study Clinical Learning Environment | 416 nursing students in 2nd and 3rd-year courses | 27 items 5 subscales: ward atmosphere, leadership style of the ward manager, premises of nursing care on the ward, premises of learning on the ward, and supervisory relationship 5-point-Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, 5-factor solution, 64% variance explained Face validity, a panel of 9 experts (comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) | Subscales 0.73–0.94 | Hypothesis testing (convergent validity) of subscale CLES (correlation between “premises of nursing care” and “ward atmosphere”, r = 0.50 p < 0.005; between premises learning and premises nursing care, r = 0.46, p < 0.05) |

| CLES | Tomietto et al., 2009 [38] Italy Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 117 nursing students in 2nd and 3rd-year courses | 27 items 5 subscales: ward atmosphere, leadership style of the ward manager, premises of nursing care on the ward, premises of learning on the ward, and supervisory relationship 5-point-Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | Total 0.96 Subscales 0.78–0.95 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Test-retest (recall period 3 weeks) r = 0.89 | |

| CLES | De Witte et al., 2011 [39] Belgium Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 768 nursing students of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 27 items 5 subscales: ward atmosphere, leadership style of the ward manager, premises of nursing care on the ward, premises of learning on the ward, and supervisory relationship 5-point-Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, varimax rotation, 5-factor solution, 71,28% variance explained Content and face validity, a panel of 12 experts (relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility) | Total 0.97 Subscales 0.80–0.95 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| CLES | Burrai et al., 2012 [13] Italy Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 59 nursing students in 2nd-year courses | 27 items 5 subscales: ward atmosphere, leadership style of the ward manager, premises of nursing care on the ward, premises of learning on the ward, and supervisory relationship 6-point-Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 6 “fully agree”) | PCA, promax rotation, 5-factor solution, 76.9% variance explained | Total 0.96 Subscales 0.81–0.96 | |

| CLES-T | Saarikoski et al., 2008 [40] Finland Development study Clinical Learning Environment | 965 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, varimax rotation, 5-factor solution; 67% variance explained | Total 0.90 Subscales 0.77–0.96 | |

| CLES-T | Johansson et al., 2010 [41] Sweden Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 177 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, varimax rotation, 5-factor solutions; 60.2% variance explained | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.75–0.96 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| CLES-T | Henriksen et al., 2012 [42] Norway Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 407 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | PCA, varimax rotation, 5-factor solution; 64% variance explained | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.85–0.96 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| CLES-T | Tomietto et al., 2012 [43] Italy Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 855 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, oblimin rotation, 7-factor solution; 67.27% variance explained CFA, 7-factor solution CFI 0.929 RMSEA 0.061 SRMR 0.045 CFA, 5-factor solution CFI 0.817 RMSEA 0.097 SRMR 0.064 | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.80–0.96 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| CLES-T | Bergjan et al., 2013 [44] Germany Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 178 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, oblimin rotation, 5-factor solution, 72.85% variance explained | Subscales 0.82–0.96 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| CLES-T | Watson et al., 2014 [45] New Zealand Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 416 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd- year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, 4-factor solution, 58.28% variance explained Face validity, a panel of 11 experts (relevance, comprehensiveness comprehensibility) | Subscales 0.82–0.93 | |

| CLES-T | Vizcaya-Moreno et al., 2015 [46] Spain Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 370 nursing students of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA 5-factor solution, 66.4% variance explained CFA 5-factor solution CFI 0.92 GFI 0.83 RMSEA 0.065 | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.80–0.97 | Cross-cultural Validity (modify direct translation method) |

| CLES-T | Papastavrou et al., 2016 [47] Greece Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 463 nursing students of 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, varimax rotation, 5-factor solution, 67.4% variance explained Content validity, a panel of 5 experts (relevance, comprehensiveness comprehensibility) | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.81–0.96 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| CLES-T | Nepal et al., 2016 [48] Nepal Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 263 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 4th-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA 5-factor solution, 85.7% variance explained | Total 0.93 Subscales 0.76–0.92 | |

| CLES-T | Lovric et al., 2016 [49] Croatia Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 136 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA 4-factor solution, 71.5% variance explained | Total 0.97 Subscales 0.77–0.96 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Test-retest: r = 0.55−0.79, p < 0.001 |

| CLES-T | Mikkonen et al., 2017 [22] Finland Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 329 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd- year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, 8-factor solution, 78% variance explained | Total 0.88 Subscales 0.79–0.97 | Hypothesis testing (convergent validity) with CLES-T (positive correlation between factor 1 CLES-T and Factor 3 CALD r = 0.62 p < 0.01; positive correlation between Factor 2 CLES-T and Factor 4 CALD, r = 0.64 p < 0.01) |

| CLES-T | Iyigun et al., 2018 [50] Turkey Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 190 nursing students in 3rd and 4th year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | PCA, promax, 5-factor solution, 62% variance explained Content validity, a panel of 9 experts (relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility) CVI 0.96 Face validity, 10 nursing students (comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) | Subscales 0.76–0.93 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Hypothesis testing (convergent validity) with CLES (p < 0.05) Test-retest: r = 0.29−0.43, p < 0.005 |

| CLES-T | Atay et al., 2018 [51] Turkey Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 602 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, 6-factor solution, 64% variance explained CFA (fit index not specified) | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.75–0.96 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| CLES-T | Zvanut et al., 2018 [52] Croatia Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 232 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 5th-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | PCA, varimax rotation, 5-factor solution, 67.69% variance explained Face validity, 232 students (comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) | Total 0.96 Subscales 0.78–0.95 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Test-retest: (p < 0.05) |

| CLES-T | Mueller et al., 2018 [53] Austria Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 385 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | PCA, promax rotation, 4-factor solution, 73.3% variance explained | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.83–0.95 | |

| CLES-T | Wong and Bressington, 2021 [54] Hong Kong Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 385 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, oblique rotation, 6-factor solution Content validity, a panel of 6 experts (relevance, comprehensiveness comprehensibility), CVI 0.93, range 0.83–1.0 Face validity, 15 nursing students (comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) | Total 0.94 Subscales 0.73–0.94 | Test-Retest (recall period 2 weeks), ICC 0.85%, 95% CI |

| CLES-T | Zhao et al., 2021 [55] China Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 694 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 27 items 4 subscales: supervisory relationship, pedagogical atmosphere, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”) | PCA, oblimin rotation, 3-factor solution, 60.01% variance explained CFA CFI 0.97 GFI 0.95 RMSEA 0.058 SRMR 0.04 | Total 0.82 Subscales 0.70–0.79 | |

| CLES-T | Ozbicakci et al., 2022 [56] Turkey Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 135 junior and senior nursing students | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | CFA, 5-factor solution GFI 0.68 RMSEA 0.092 Content validity, a panel of 3 experts (relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility)) Face validity, 10 nursing students (comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) | Total 0.86 Subscales 0.48–0.94 | |

| CLES-T | Guejdad et al., 2022 [57] Morocco Validation study Clinical Learning Environment | 1550 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 34 items 5 subscales: supervisory relation, pedagogical atmosphere on the ward, role of nurse teacher, leadership style of the ward manager, and premises of nursing on the ward 5-point Likert (from 1 “fully disagree” to 5 “fully agree”) | EFA, promax rotation, 5-factor solution, 55% variance explained CFA, 5-factor solution GFI 0.946 CFI 0.961 RMSEA 0.035 Face validity, 28 nursing students (comprehensiveness and comprehensibility) | Total 0.93 Subscales 0.71–0.92 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Test-retest: ICC 0.84 |

| DREEM | Wang et al., 2009 [58] China Validation study Educational environment | 214 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 50 items 5 subscales: perception of learning, perception of teachers, social self-perception, perception of atmosphere, and academic self-perception 5-point Likert (from 0 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree) | PCA, oblimin, 5-factor solution, 52.19% variance explained | Total 0.95 Subscales 0.62–0.90 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) |

| DREEM | Rotthoff et al., 2011 [59] Germany Validation study Educational environment | 1119 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 50 items 5 subscales: perception of learning, perception of teachers, social self-perception, perception of atmosphere, and academic self-perception 5-point Likert (from 0 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree) | EFA, orthogonal rotation, 5-factor solution, 41.3% variance explained | Total 0.92 Subscales 0.57–0.84 | Cross-cultural Validity (forward and backward translation) Hypothesis testing (known-groups technique: between students and number of semesters attended), perception of teaching is negative as the number of semesters attended increases, r = −0.18, p < 0.001 |

| DREEM | Gosak et al., 2021 [60] Slovenia Validation study Educational environment | 174 nursing students in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year courses | 50 items 5 subscales: perception of learning, perception of teachers, social self-perception, perception of atmosphere, and academic self-perception 5-point Likert (from 0 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree) | Content validity, a panel of 6 experts, CVI 1.0 except for item n. 20 | Total 0.95 | Cross-cultural Validity (reverse translation technique) |

| EAPAP | Arribas-Marìn et al., 2017 [61] Spain Development study Educational environment | 710 nursing students in 2nd-year courses | 23 items 4 subscales: peer support, academic institution support, preceptor support, and clinical facilitator support 10-point Likert (from 1 “never” to 10 “always”) | PCA, promax rotation, 4 factors solution, 74.77% variance explained CFA, 4-factor solution CFI 0.960 RMSEA 0.051 | Total 0.92 Subscales 0.88–0.96 | |

| ESECS | Baptista et al., 2014 [62] Spain Development study Clinical and simulated environment | 181 nursing students in 4th and 5th-year courses | 17 items 3 Subscales: practical dimension, realism dimension, and cognitive dimension 5-point Likert (from 1 “unsatisfactory” to 5 “very satisfactory”) | PCA, orthogonal varimax rotation, 3-factor solution (practical dimension, realism dimension, and cognitive dimension) | Total 0.91 Subscales 0.73–0.89 | |

| ESECS | Montejano Lozoya et al., 2019 [63] Portugal Validation study Clinical and simulated environment | 174 student nurses in 2nd, 3rd, and 4th-year courses | 17 items 3 Subscales: practical dimension, realism dimension, and cognitive dimension 5-point Likert (from 1 “unsatisfactory” to 5 “very satisfactory”) | PCA, varimax rotation, 4-factor solution, 66.6% variance explained CFA, 4-factor solution CFI 0.877 RMSEA 0.094 Face and content validity (panel of 8 experts, relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility) Face validity (53 nursing students, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility) | Total 0.91 | |

| SECEE | Sand-Jeclklin, 2009 [64] USA Validation study Clinical learning environment | 2768 inventories of nursing sophomore, junior, and baccalaureate students | 32 items 3 subscales: instructor facilitation, preceptor facilitation, and learning opportunities 5-point Likert (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”) | EFA, 4-factor solution CFA, varimax rotation, 3-factor solution with 59% variance explained SRMR 0.037 | Total 0.94 Subscales 0.82–0.94 | Hypothesis testing according to student level (sophomore, junior, and senior) p = 0.05 seniors value more positively than sophomores |

| SECEE | Govina et al., 2016 [65] Greece Validation study Clinical learning environment | 130 senior nursing students | 32 items 3 subscales: instructor facilitation (IFL), preceptor facilitation (PFL), and learning opportunities (LO) 5-point Likert (from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”) | CFA, 3-factor solution CFI 0.92 RMSEA 0.052 | Total 0.92 Subscales 0.84–0.89 | Cross-cultural Validity (backward forward translation) Reliability (2 weeks di intervallo): ICC: 0.85–0.90, p < 0.0005 Hypothesis testing (discriminant validity) with CLES (highest between Ward atmosphere-PFL 0.537, and lowest between learning on the ward-IFL 0.163) |

| Tool | Relevance | Comprehensiveness | Comprehensibility | Overall Content Validity | Structural Validity | Internal Consistency | Other Measurement | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CALD | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | −/L | +/L | Hypothesis testing +/L Cross-cultural validity +/L | A |

| CEF | +/L | ±/L | ±/L | ±/L | +/H | B | ||

| CLE | +/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | −/M | −/M | C | |

| CLECS | +/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | −/L | +/L | Cross-cultural validity +/L Reliability -/L Hypothesis testing convergent +/L Hypothesis testing discriminant -/L | B |

| CLEDI | +/L | ±/L | ±/L | ±/L | ?/M | +/M | Criterion validity +/M Reliability +/M Hypothesis testing +/M | B |

| CLEI | +/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | ?/VL | −/VL | Hypothesis testing +/VL | C |

| CLEI-19 | +/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | +/H | +/H | Hypothesis testing +/H | B |

| CLEQEI | +/L | ±/L | ±/L | ±/L | +/H | +/H | Reliability +/H Hypothesis testing +/H | B |

| CLES | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | ?/L | +/L | Cross-cultural testing +/L Reliability +/L Hypothesis testing +/L | B |

| CLES-T | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | ±/M | −/L | +/L | Reliability −/VL Hypothesis testing ?/VL Cross-cultural validity +/VL | B |

| DREEM | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | −/L | +/L | Hypothesis testing +/L Cross-cultural validity +/VL | A |

| EAPAP | +/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | ±/VL | +/H | +/H | B | |

| ESECS | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | −/VL | −/VL | B | |

| SECEE | +/M | +/M | +/M | +/M | ?/H | +/H | Cross-cultural validity +/H Reliability −/H Hypothesis testing +/H | A |

| Categories | Tools | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CALD | CEF | CLE | CLECS | CLEDI | CLEI | CLEI-19 | CLEQEI | CLES | CLES-T | DREEM | EAPAP | ESECS | SECEE | F | |

| Learning the nursing process | X | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Self-learning | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Self-efficacy in practical learning | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Self-efficacy in theoretical learning | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Students’ motivation | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||||||

| Learning opportunities | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 9 | |||||

| Learning barriers | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||||||

| Quality of relationship with teachers | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Quality of relationship with tutors | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | ||||||

| Quality of the clinical learning environment | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | ||||||

| Quality of the classroom learning environment | X | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Quality of the teaching strategies | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Quality of the tutoring strategies | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 11 | |||

| Quality of relationship with Staff nurse | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||||||

| Quality of relationship with patients and relatives | X | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Safety and quality of care | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | ||||||

| Satisfaction with the practical training experience | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | |||||||

| Satisfaction with theoretical learning | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Academic support (access to resources) | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||||||

| Academic support (information received) | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Academic support (student support) | X | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Support from the staff nurse | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||||||

| Support from fellow students | X | X | X | 3 | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lommi, M.; De Benedictis, A.; Ricci, S.; Guarente, L.; Latina, R.; Covelli, G.; Pozzuoli, G.; De Maria, M.; Giovanniello, D.; Rocco, G.; et al. Appraisal and Evaluation of the Learning Environment Instruments of the Student Nurse: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11071043

Lommi M, De Benedictis A, Ricci S, Guarente L, Latina R, Covelli G, Pozzuoli G, De Maria M, Giovanniello D, Rocco G, et al. Appraisal and Evaluation of the Learning Environment Instruments of the Student Nurse: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology. Healthcare. 2023; 11(7):1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11071043

Chicago/Turabian StyleLommi, Marzia, Anna De Benedictis, Simona Ricci, Luca Guarente, Roberto Latina, Giuliana Covelli, Gianluca Pozzuoli, Maddalena De Maria, Dominique Giovanniello, Gennaro Rocco, and et al. 2023. "Appraisal and Evaluation of the Learning Environment Instruments of the Student Nurse: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology" Healthcare 11, no. 7: 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11071043

APA StyleLommi, M., De Benedictis, A., Ricci, S., Guarente, L., Latina, R., Covelli, G., Pozzuoli, G., De Maria, M., Giovanniello, D., Rocco, G., Stievano, A., Sabatino, L., Notarnicola, I., Gualandi, R., Tartaglini, D., & Ivziku, D. (2023). Appraisal and Evaluation of the Learning Environment Instruments of the Student Nurse: A Systematic Review Using COSMIN Methodology. Healthcare, 11(7), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11071043