ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

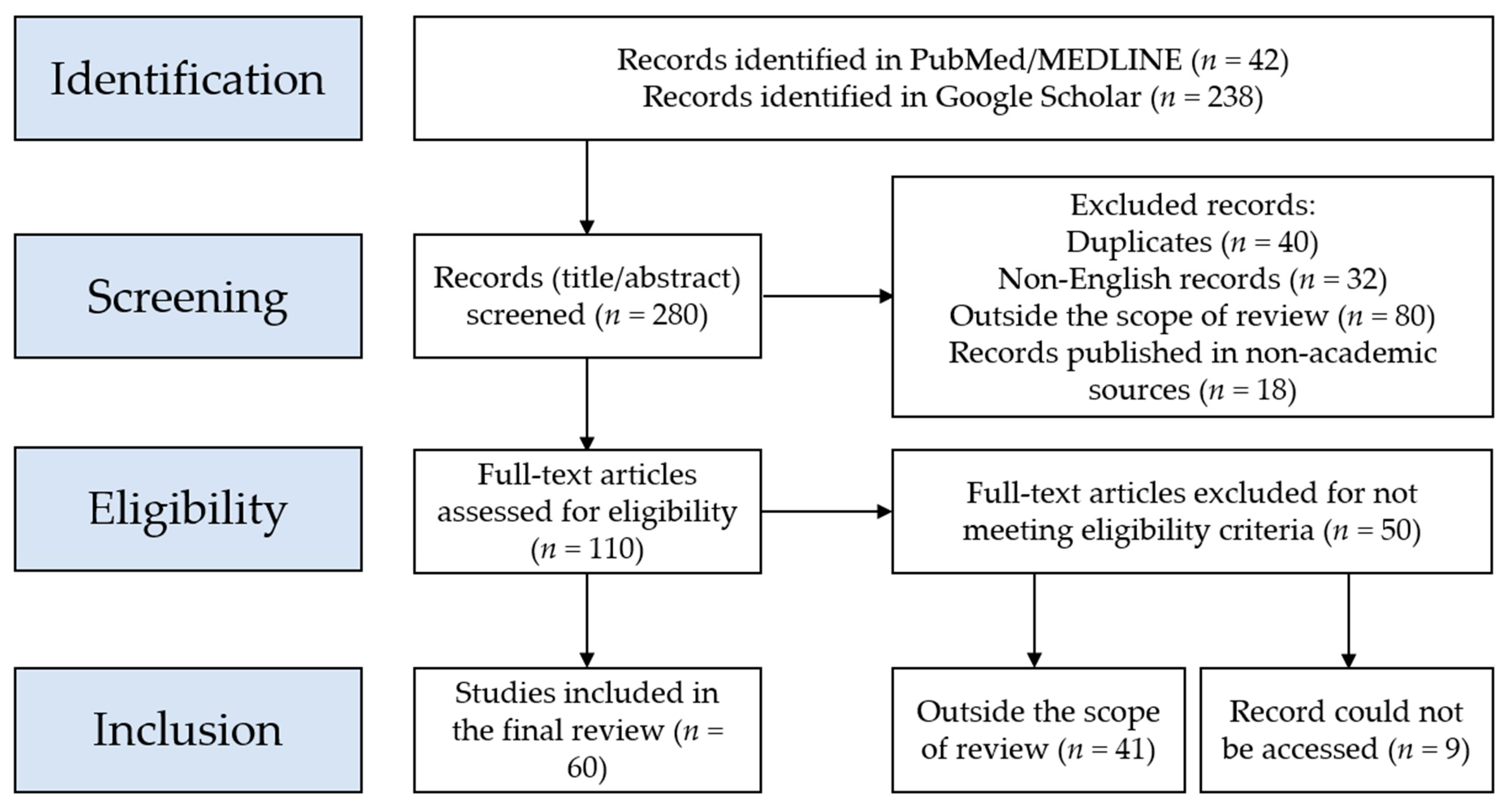

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Summary of the Record Screening Approach

2.3. Summary of the Descriptive Search for ChatGPT Benefits and Risks in the Included Records

3. Results

3.1. Summary of the ChatGPT Benefits and Limitations/Concerns in Health Care

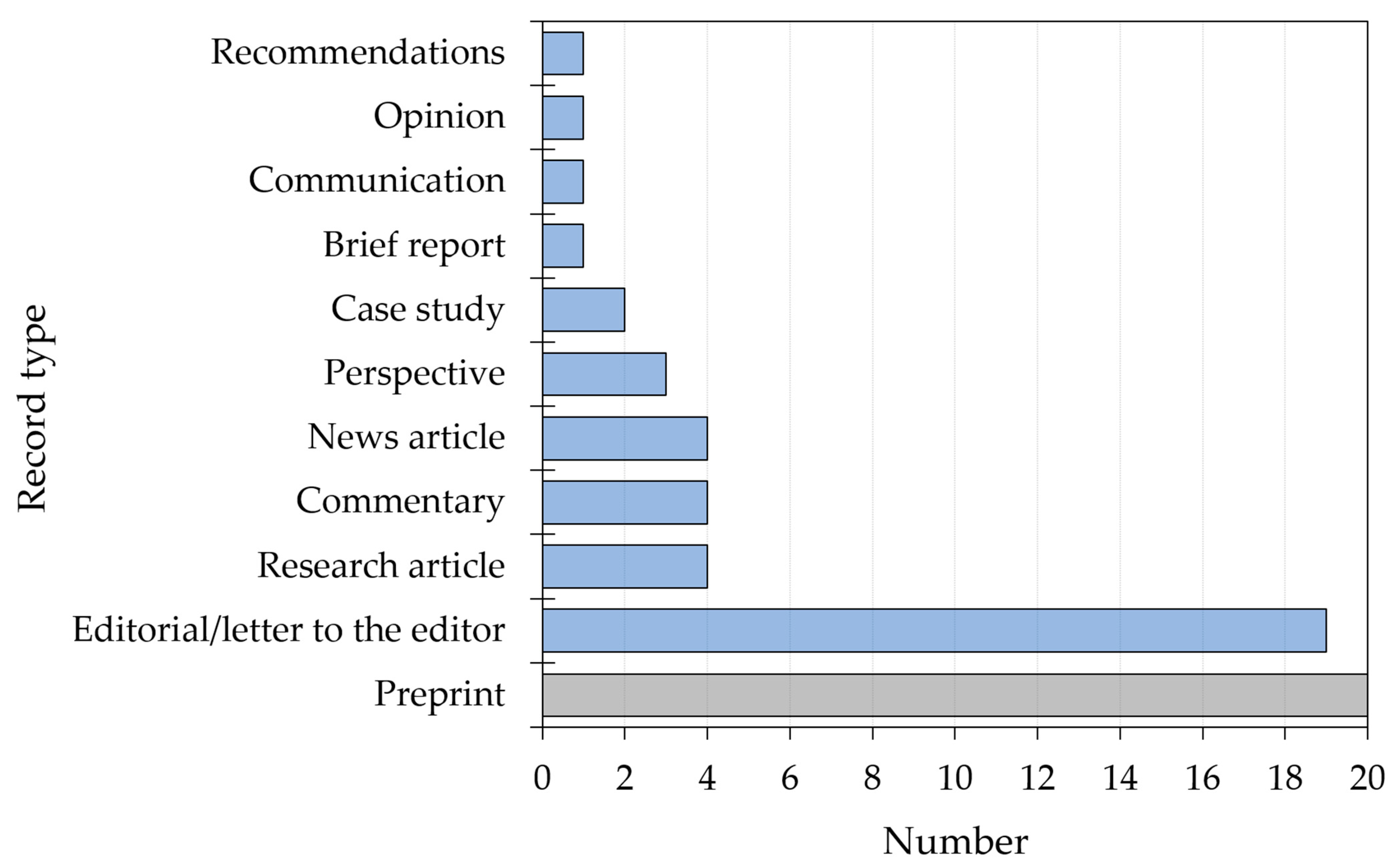

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Records

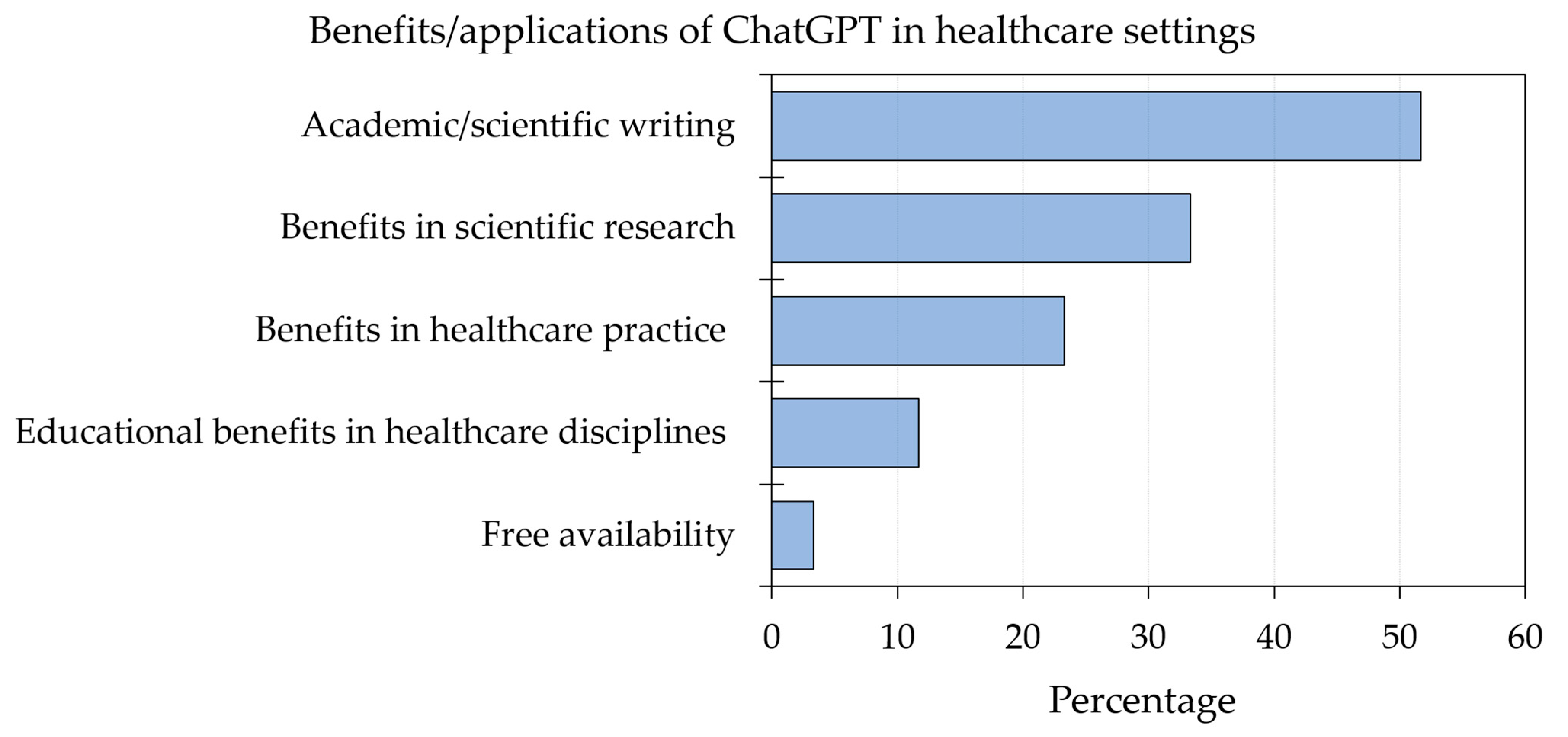

3.3. Benefits and Possible Applications of ChatGPT in Health Care Education, Practice, and Research Based on the Included Records

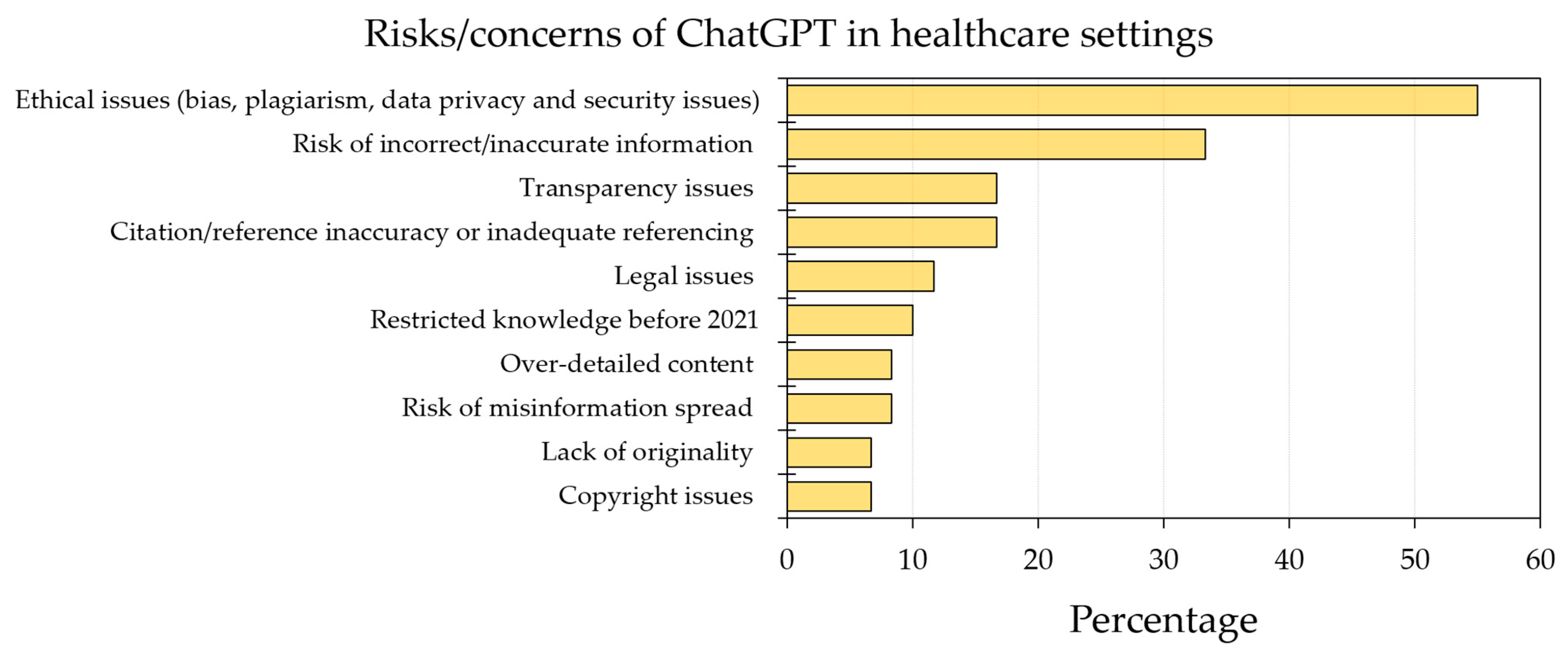

3.4. Risks and Concerns toward ChatGPT in Health Care Education, Practice, and Research Based on the Included Records

4. Discussion

4.1. Benefits of ChatGPT in Scientific Research

4.2. Limitations of ChatGPT Use in Scientific Research

4.3. Benefits of ChatGPT in Health Care Practice

4.4. Concerns Regarding ChatGPT Use in Health Care Practice

4.5. Benefits and Concerns Regarding ChatGPT Use in Health Care Education

4.6. Future Perspectives

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarker, I.H. AI-Based Modeling: Techniques, Applications and Research Issues Towards Automation, Intelligent and Smart Systems. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korteling, J.E.; van de Boer-Visschedijk, G.C.; Blankendaal, R.A.M.; Boonekamp, R.C.; Eikelboom, A.R. Human- versus Artificial Intelligence. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 622364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, J.; Minsky, M.L.; Rochester, N.; Shannon, C.E. A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955. AI Mag. 2006, 27, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, P. The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World, 1st ed.; Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. OpenAI: Models GPT-3. Available online: https://beta.openai.com/docs/models (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogu, I.A.P.; Olu-Owolabi, F.E.; Assibong, P.A.; Agoha, B.C.; Sholarin, M.; Elegbeleye, A.; Igbokwe, D.; Apeh, H.A. Artificial intelligence, alienation and ontological problems of other minds: A critical investigation into the future of man and machines. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computing Networking and Informatics (ICCNI), Lagos, Nigeria, 29–31 October 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J. Artificial intelligence: Implications for the future of work. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, M.C. The impact of artificial intelligence on human society and bioethics. Tzu Chi. Med J. 2020, 32, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lin, Y. The Benefits and Challenges of ChatGPT: An Overview. Front. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2023, 2, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobore, T.O. On Energy Efficiency and the Brain’s Resistance to Change: The Neurological Evolution of Dogmatism and Close-Mindedness. Psychol. Rep. 2019, 122, 2406–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokel-Walker, C. AI bot ChatGPT writes smart essays—Should professors worry? Nature, 9 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokel-Walker, C.; Van Noorden, R. What ChatGPT and generative AI mean for science. Nature 2023, 614, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, J.; Dethlefs, N. This new conversational AI model can be your friend, philosopher, and guide … and even your worst enemy. Patterns 2023, 4, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Barakat, M.; Fayyad, D.; Hallit, S.; Harapan, H.; Hallit, R.; Mahafzah, A. ChatGPT Output Regarding Compulsory Vaccination and COVID-19 Vaccine Conspiracy: A Descriptive Study at the Outset of a Paradigm Shift in Online Search for Information. Cureus 2023, 15, e35029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.B.; Wei, W.Q.; Weeraratne, D.; Frisse, M.E.; Misulis, K.; Rhee, K.; Zhao, J.; Snowdon, J.L. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in health and medicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranjape, K.; Schinkel, M.; Nannan Panday, R.; Car, J.; Nanayakkara, P. Introducing Artificial Intelligence Training in Medical Education. JMIR Med. Educ. 2019, 5, e16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borji, A. A Categorical Archive of ChatGPT Failures. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.-W. Publish or Perish. Available online: https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Chen, T.J. ChatGPT and Other Artificial Intelligence Applications Speed up Scientific Writing. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jcma/Citation/9900/ChatGPT_and_other_artificial_intelligence.174.aspx (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Thorp, H.H. ChatGPT is fun, but not an author. Science 2023, 379, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, F.C. ChatGPT Is Shaping the Future of Medical Writing but Still Requires Human Judgment. Radiology 2023, 230171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubowitz, J. ChatGPT, An Artificial Intelligence Chatbot, Is Impacting Medical Literature. Arthroscopy, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature editorial. Tools such as ChatGPT threaten transparent science; here are our ground rules for their use. Nature 2023, 613, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, P.; Van Bulck, L. ChatGPT: Can artificial intelligence language models be of value for cardiovascular nurses and allied health professionals. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/eurjcn/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurjcn/zvad022/7031481 (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Cahan, P.; Treutlein, B. A conversation with ChatGPT on the role of computational systems biology in stem cell research. Stem. Cell. Rep. 2023, 18, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C. Exploring ChatGPT for information of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2023, 185, 109729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawan, J. Exploring the future of nursing: Insights from the ChatGPT model. Belitung Nurs. J. 2023, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, R.S.; White, T.G.; Shah, H.A.; Langer, D.J. I Asked a ChatGPT to Write an Editorial About How We Can Incorporate Chatbots Into Neurosurgical Research and Patient Care. Neurosurgery 2023, 92, 993–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijačko, N.; Gosak, L.; Štiglic, G.; Picard, C.T.; John Douma, M. Can ChatGPT Pass the Life Support Exams without Entering the American Heart Association Course? Resuscitation 2023, 185, 109732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbakwe, A.B.; Lourentzou, I.; Celi, L.A.; Mechanic, O.J.; Dagan, A. ChatGPT passing USMLE shines a spotlight on the flaws of medical education. PLoS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S. Issues in the 3rd year of the COVID-19 pandemic, including computer-based testing, study design, ChatGPT, journal metrics, and appreciation to reviewers. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2023, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, S. Open artificial intelligence platforms in nursing education: Tools for academic progress or abuse? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 66, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Heacock, L.; Elias, J.; Hentel, K.D.; Reig, B.; Shih, G.; Moy, L. ChatGPT and Other Large Language Models Are Double-edged Swords. Radiology 2023, 230163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordijn, B.; Have, H.t. ChatGPT: Evolution or revolution? Med. Health Care Philos. 2023, 26, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwil, M.; Aljanabi, M.; Ali, A. ChatGPT: Exploring the Role of Cybersecurity in the Protection of Medical Information. Mesop. J. CyberSecurity 2023, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Digital Health. ChatGPT: Friend or foe? Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e112–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, M.; Ghazi, M.; Ali, A.; Abed, S. ChatGpt: Open Possibilities. Iraqi J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2023, 4, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Analysis of ChatGPT Tool to Assess the Potential of its Utility for Academic Writing in Biomedical Domain. Biol. Eng. Med. Sci. Rep. 2023, 9, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, C.; Winker, M.; Aggarwal, R.; Ferris, L.; Heinemann, M.; Lapeña, J.; Pai, S.; Ing, E.; Citrome, L. Chatbots, ChatGPT, and Scholarly Manuscripts WAME Recommendations on ChatGPT and Chatbots in Relation to Scholarly Publications. Maced J. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S. ChatGPT and the Future of Medical Writing. Radiology 2023, 223312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokel-Walker, C. ChatGPT listed as author on research papers: Many scientists disapprove. Nature 2023, 613, 620–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dis, E.A.M.; Bollen, J.; Zuidema, W.; van Rooij, R.; Bockting, C.L. ChatGPT: Five priorities for research. Nature 2023, 614, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, B.; Wang, S. Chatting about ChatGPT: How may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries? Library Hi. Tech. News, 2023; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebrenz, M.; Schleifer, R.; Buadze, A.; Bhugra, D.; Smith, A. Generating scholarly content with ChatGPT: Ethical challenges for medical publishing. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e105–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manohar, N.; Prasad, S.S. Use of ChatGPT in Academic Publishing: A Rare Case of Seronegative Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Patient With HIV Infection. Cureus 2023, 15, e34616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, H.M.; Cooper, J.S. Acute Pulmonary Edema After Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment: A Case Report Written With ChatGPT Assistance. Cureus 2023, 15, e34752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzinger, A.; Keiblinger, K.; Holub, P.; Zatloukal, K.; Müller, H. AI for life: Trends in artificial intelligence for biotechnology. N. Biotechnol. 2023, 74, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D. Artificial Intelligence Discusses the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Translational Medicine: A JACC: Basic to Translational Science Interview With ChatGPT. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Basic Trans. Sci. 2023, 8, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.B.; Lam, K. ChatGPT: The future of discharge summaries? Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e107–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, A. Rapamycin in the context of Pascal’s Wager: Generative pre-trained transformer perspective. Oncoscience 2022, 9, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, J.E.; Udaondo, Z.; Pedrós-Alió, C.; Höfer, J.; Benison, K.C.; Lloyd, K.G.; Cordero, R.J.B.; de Campos, C.B.L.; Yakimov, M.M.; Amils, R. Scientific novelty beyond the experiment. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S. Are ChatGPT’s knowledge and interpretation ability comparable to those of medical students in Korea for taking a parasitology examination?: A descriptive study. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2023, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Jawaid, M.; Khan, A.; Sajjad, M. ChatGPT-Reshaping medical education and clinical management. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 39, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, A.; Safranek, C.W.; Huang, T.; Socrates, V.; Chi, L.; Taylor, R.A.; Chartash, D. How Does ChatGPT Perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination? The Implications of Large Language Models for Medical Education and Knowledge Assessment. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e45312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, T.H.; Cheatham, M.; Medenilla, A.; Sillos, C.; De Leon, L.; Elepaño, C.; Madriaga, M.; Aggabao, R.; Diaz-Candido, G.; Maningo, J.; et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchandot, B.; Matsushita, K.; Carmona, A.; Trimaille, A.; Morel, O. ChatGPT: The Next Frontier in Academic Writing for Cardiologists or a Pandora’s Box of Ethical Dilemmas. Eur. Heart J. Open 2023, 3, oead007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Scells, H.; Koopman, B.; Zuccon, G. Can ChatGPT Write a Good Boolean Query for Systematic Review Literature Search? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.; Cotton, P.; Shipway, J. Chatting and Cheating. Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. EdArXiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.A.; Howard, F.M.; Markov, N.S.; Dyer, E.C.; Ramesh, S.; Luo, Y.; Pearson, A.T. Comparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to original abstracts using an artificial intelligence output detector, plagiarism detector, and blinded human reviewers. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.; Rotman, J. Should Artificial Intelligent (AI) Agents be Your Co-author? Arguments in favour, informed by ChatGPT. SSRN, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aczel, B.; Wagenmakers, E. Transparency Guidance for ChatGPT Usage in Scientific Writing. PsyArXiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, L.; Baglivo, F.; Arzilli, G.; Privitera, G.P.; Ferragina, P.; Tozzi, A.E.; Rizzo, C. ChatGPT and the Rise of Large Language Models: The New AI-Driven Infodemic Threat in Public Health. SSRN, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, J. ChatGPT for Clinical Vignette Generation, Revision, and Evaluation. medRxiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Thakur, A. ChatGPT in Drug Discovery. ChemRxiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Kim, J.; Kamineni, M.; Pang, M.; Lie, W.; Succi, M.D. Evaluating ChatGPT as an Adjunct for Radiologic Decision-Making. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antaki, F.; Touma, S.; Milad, D.; El-Khoury, J.; Duval, R. Evaluating the Performance of ChatGPT in Ophthalmology: An Analysis of its Successes and Shortcomings. medRxiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, Ö.; Karaarslan, E. OpenAI ChatGPT generated literature review: Digital twin in healthcare. SSRN, 2022; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmarchi, F.; Bucci, A.; Golinelli, D. A step-by-step Researcher’s Guide to the use of an AI-based transformer in epidemiology: An exploratory analysis of ChatGPT using the STROBE checklist for observational studies. medRxiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, D.; Solomon, B.D. Analysis of large-language model versus human performance for genetics questions. medRxiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y.H.; Samaan, J.S.; Ng, W.H.; Ting, P.-S.; Trivedi, H.; Vipani, A.; Ayoub, W.; Yang, J.D.; Liran, O.; Spiegel, B.; et al. Assessing the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions regarding cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. medRxiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bašić, Ž.; Banovac, A.; Kružić, I.; Jerković, I. Better by You, better than Me? ChatGPT-3 as writing assistance in students’ essays. arXiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisan, U.; Amri, M. ChatGPT and Medical Education: A Double-Edged Sword. Researchgate, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeblick, K.; Schachtner, B.; Dexl, J.; Mittermeier, A.; Stüber, A.T.; Topalis, J.; Weber, T.; Wesp, P.; Sabel, B.; Ricke, J.; et al. ChatGPT Makes Medicine Easy to Swallow: An Exploratory Case Study on Simplified Radiology Reports. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Aslam, M. Is ChatGPT a Good Tool for T&CM Students in Studying Pharmacology? SSRN, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z. Why and how to embrace AI such as ChatGPT in your academic life. PsyArXiv, 2023; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taecharungroj, V. “What Can ChatGPT Do?”; Analyzing Early Reactions to the Innovative AI Chatbot on Twitter. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Montomoli, J.; Bellini, V.; Bignami, E. Evaluating the Feasibility of ChatGPT in Healthcare: An Analysis of Multiple Clinical and Research Scenarios. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachshon, A.; Batzofin, B.; Beil, M.; van Heerden, P.V. When Palliative Care May Be the Only Option in the Management of Severe Burns: A Case Report Written With the Help of ChatGPT. Cureus 2023, 15, e35649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.G. Using ChatGPT for language editing in scientific articles. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 45, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.R.; Dobbs, T.D.; Hutchings, H.A.; Whitaker, I.S. Using ChatGPT to write patient clinic letters. Lancet Digit. Health, 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; Hayawi, K. Let’s have a chat! A Conversation with ChatGPT: Technology, Applications, and Limitations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, I.L.; Mercolli, L.; Pyka, T.; Prenosil, G.; Shi, K.; Rominger, A.; Afshar-Oromieh, A. Large language models (LLM) and ChatGPT: What will the impact on nuclear medicine be? Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging, 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Barakat, M.; Al-Tammemi, A.B. ChatGPT applications in medical, dental, pharmacy, and public health education: A descriptive study. Narra J. 2023, 3, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Gurgel, R.Q.; Araújo, A.A.S.; Correia, D.; Martins-Filho, P.R. ChatGPT: The new panacea of the academic world. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2023, 56, e0060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homolak, J. Opportunities and risks of ChatGPT in medicine, science, and academic publishing: A modern Promethean dilemma. Croat. Med. J. 2023, 64, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checcucci, E.; Verri, P.; Amparore, D.; Cacciamani, G.E.; Fiori, C.; Breda, A.; Porpiglia, F. Generative Pre-training Transformer Chat (ChatGPT) in the scientific community: The train has left the station. Minerva. Urol. Nephrol. 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. Peer review: A flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J. R. Soc. Med. 2006, 99, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogenis, A.F.; Quaile, A.; Scarlat, M.M. The good, the bad and the rude peer-review. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalida, A.; Colomer, M. Improving the peer-review process and editorial quality: Key errors escaping the review and editorial process in top scientific journals. PeerJ. 2016, 4, e1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, M.; Pareek, A.; Dahmen, J.; Kayaalp, M.E.; Winkler, P.W.; Hirschmann, M.T.; Karlsson, J. A deeper dive into ChatGPT: History, use and future perspectives for orthopaedic research. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, C. Interstellar; 169 minutes; Legendary Entertainment: Burbank, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kostick-Quenet, K.M.; Gerke, S. AI in the hands of imperfect users. Npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author(s) [Record] | Design, Aims | Applications, Benefits | Risks, Concerns, Limitations | Suggested Action, Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen [23] | Editorial on ChatGPT applications in scientific writing | ChatGPT helps to overcome language barriers promoting equity in research | Ethical concerns (ghostwriting); doubtful accuracy; citation problems | Embrace this innovation with an open mind; authors should have proper knowledge on how to exploit AI 6 tools |

| Thorp [24] | Editorial: “ChatGPT is not an author” | - | Content is not original; incorrect answers that sound plausible; issues of referencing; risk of plagiarism | Revise assignments in education In Science journals, the use of ChatGPT is considered as a scientific misconduct |

| Kitamura [25] | Editorial on ChatGPT and the future of medical writing | Improved efficiency in medical writing; translation purposes | Ethical concerns, plagiarism; lack of originality; inaccurate content; risk of bias | “AI in the Loop: Humans in Charge” |

| Lubowitz [26] | Editorial, ChatGPT impact on medical literature | - | Inaccurate content; risk of bias; spread of misinformation and disinformation; lack of references; redundancy in text | Authors should not use ChatGPT to compose any part of scientific submission; however, it can be used under careful human supervision to ensure the integrity and originality of the scientific work |

| Nature [27] | Nature editorial on the rules of ChatGPT use to ensure transparent science | ChatGPT can help to summarize research papers; to generate helpful computer codes | Ethical issues; transparency issues | LLM 7 tools will be accepted as authors; if LLM tools are to be used, it should be documented in the methods or acknowledgements; advocate for transparency in methods, and integrity and truth from researchers |

| Moons and Van Bulck [28] | Editorial on ChatGPT potential in cardiovascular nursing practice and research | ChatGPT can help to summarize a large text; it can facilitate the work of researchers; it can help in data collection | Information accuracy issues; the limited knowledge up to the year 2021; limited capacity | ChatGPT can be a valuable tool in health care practice |

| Cahan and Treutlein [29] | Editorial reporting a conversation with ChatGPT on stem cell research | ChatGPT helps to save time | Repetition; several ChatGPT responses lacked depth and insight; lack of references | ChatGPT helped to write an editorial saving valuable time |

| Ahn [30] | A letter to the editor reporting a conversation of ChatGPT regarding CPR 1 | Personalized interaction; quick response time; it can help to provide easily accessible and understandable information regarding CPR to the general public | Inaccurate information might be generated with possible serious medical consequences | Explore the potential utility of ChatGPT to provide information and education on CPR |

| Gunawan [31] | An editorial reporting a conversation with ChatGPT regarding the future of nursing | ChatGPT can help to increase efficiency; it helps to reduce errors in care delivery | Lack of emotional and personal support | ChatGPT can provide valuable perspectives in health care |

| D’Amico et al. [32] | An editorial reporting a conversation of ChatGPT regarding incorporating Chatbots into neurosurgical practice and research | ChatGPT can help to provide timely and accurate information for the patients about their treatment and care | Possibility of inaccurate information; privacy concerns; ethical issues; legal issues; risk of bias | Neurosurgery practice can be leading in utilizing ChatGPT into patient care and research |

| Fijačko et al. [33] | A letter to the editor to report the accuracy of ChatGPT responses with regards to life support exam questions by the AHA 2 | ChatGPT provides relevant and accurate responses on occasions | Referencing issues; over-detailed responses | ChatGPT did not pass any of the exams; however, it can be a powerful self-learning tool to prepare for the life support exams |

| Mbakwe et al. [34] | An editorial on ChatGPT ability to pass the USMLE 3 | - | Risk of bias; lack of thoughtful reasoning | ChatGPT passing the USMLE revealed the deficiencies in medical education and assessment; there is a need to reevaluate the current medical students’ training and educational tools |

| Huh [35] | An editorial of JEEHP 4 policy towards ChatGPT use | - | Reponses were not accurate in some areas | JEEHP will not accept ChatGPT as an author; however, ChatGPT content can be used if properly cited and documented |

| O’Connor * [36] | An editorial written with ChatGPT assistance on ChatGPT in nursing education | ChatGPT can help to provide a personalized learning experience | Risk of plagiarism; biased or misleading results | Advocate ethical and responsible use of ChatGPT; improve assessment in nursing education |

| Shen et al. [37] | An editorial on ChatGPT strengths and limitations | ChatGPT can help in the generation of medical reports; providing summaries of medical records; drafting letters to the insurance provider; improving the interpretability of CAD 5 systems | Risk of hallucination (inaccurate information that sounds plausible scientifically); the need to carefully construct ChatGPT prompts; possible inaccurate or incomplete results; dependence on the training data; risk of bias; risk of research fraud | Careful use of ChatGPT is needed to exploit its powerful applications |

| Gordijn and Have [38] | Editorial on the revolutionary nature of ChatGPT | - | Risk of factual inaccuracies; risk of plagiarism; risk of fraud; copyright infringements possibility | In the near future, LLM can write papers with the ability to pass peer review; therefore, the scientific community should be prepared to address this serious issue |

| Mijwil et al. [39] | An editorial on the role of cybersecurity in the protection of medical information | Versatility; efficiency; high quality of text generated; cost saving; innovation potential; improved decision making; improved diagnostics; predictive modeling; improved personalized medicine; streamline clinical workflow increasing efficiency; remote monitoring | Data security issues | The role of cybersecurity to protect medical information should be emphasized |

| The Lancet Digital Health [40] | An editorial on the strengths and limitations of ChatGPT | ChatGPT can help to improve language and readability | Over-detailed content; incorrect or biased content; potential to generate harmful errors; risk of spread of misinformation; risk of plagiarism; issues with integrity of scientific records | Widespread use of ChatGPT is inevitable; proper documentation of ChatGPT use is needed; ChatGPT should not be listed or cited as an author or co-author |

| Aljanabi et al. [41] | An editorial on the possibilities provided by ChatGPT | ChatGPT can help in academic writing; helpful in code generation | Inaccurate content including inability handle mathematical calculations to reliably | ChatGPT will receive a growing interest in the scientific community |

| Author(s) [Record] | Design, Aims | Applications, Benefits | Risks, Concerns, Limitations | Suggested Action, Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stokel-Walker [13] | News explainer | Well-organized content with decent references; a free package | Imminent end of conventional educational assessment; concerns regarding the effect on human knowledge and ability | The need to revise educational assessment tools to prioritize critical thinking or reasoning |

| Kumar [42] | Brief report; assessment of ChatGPT for academic writing in biomedicine | Original, precise, and accurate responses with systematic approach; helpful for training and to improving topic clarity; efficiency in time; promoting motivation to write | Failure to follow the instructions correctly on occasions; failure to cite references in-text; inaccurate references; lack of practical examples; lack of personal experience highlights; superficial responses | ChatGPT can help in improving academic writing skills; advocate for universal design for learning; proper use of ChatGPT under academic mentoring |

| Zielinski et al. [43] | WAME 1 recommendations on ChatGPT | ChatGPT can be a useful tool for researchers | Risk of incorrect or non-sensical answers; restricted knowledge to the period before 2021; lack of legal personality; risk of plagiarism | ChatGPT does not meet ICMJE 4 criteria and cannot be listed as an author; authors should be transparent regarding ChatGPT use and take responsibility for its content; editors need appropriate detection tools for ChatGPT-generated content |

| Biswas [44] | A perspective record on the future of medical writing in light of ChatGPT | Improved efficiency in medical writing | Suboptimal understanding of the medical field; ethical concerns; risk of bias; legal issues; transparency issues | A powerful tool in the medical field; however, several limitations of ChatGPT should be considered |

| Stokel-Walker [45] | A news article on the view of ChatGPT as an author | - | Risk of plagiarism; lack of accountability; concerns about misuse in the academia | ChatGPT should not be considered as an author |

| van Dis et al. [46] | A commentary on the priorities for ChatGPT research | ChatGPT can help to accelerate innovation; to increase efficiency in publication time; it can make science more equitable and increase the diversity of scientific perspectives; more free time for experimental designs; it could optimize academic training | Compromised research quality; transparency issues; risk of spread of misinformation; inaccuracies in content, risk of bias and plagiarism; ethical concerns; possible future monopoly; lack of transparency | ChatGPT ban will not work; develop rules for accountability, integrity, transparency and honesty; carefully consider which academic skills remain essential to researchers; widen the debate in the academia; an initiative is needed to address the development and responsible use of LLM 5 for research |

| Lund and Wang [47] | News article on ChatGPT impact in academia | Useful for literature review; can help in data analysis; can help in translation | Ethical concerns, issues about data privacy and security; risk of bias; transparency issues | ChatGPT has the potential to advance academia; consider how to use ChatGPT responsibly and ethically |

| Liebrenz et al. [48] | A commentary on the ethical issues of ChatGPT use in medical publishing | ChatGPT can help to overcome language barriers | Ethical issues (copyright, attribution, plagiarism, and authorship); inequalities in scholarly publishing; risk of spread of misinformation; inaccurate content | Robust AI authorship guidelines are needed in scholarly publishing; COPE AI 6 should be followed; AI cannot be listed as an author and it must be properly acknowledged upon its use |

| Manohar and Prasad [49] | A case study written with ChatGPT assistance | ChatGPT helped to generate a clear, comprehensible text | Lack of scientific accuracy and reliability; citation inaccuracies | ChatGPT use is discouraged due to risk of false information and non-existent citations; it can be misleading in health care practice |

| Akhter and Cooper [50] | A case study written with ChatGPT assistance | ChatGPT helped to provide a relevant general introductory summary | Inability to access relevant literature; the limited knowledge up to 2021; citation inaccuracies; limited ability to critically discuss results | Currently, ChatGPT cannot replace independent literature reviews in scientific research |

| Holzinger et al. [51] | An article on AI 2/ChatGPT use in biotechnology | Biomedical image analysis; diagnostics and disease prediction; personalized medicine; drug discovery and development | Ethical and legal issues; limited data availability to train the models; the issue of reproducibility of the runs | The scientists aspire for fairness, open science, and open data |

| Mann [52] | A perspective on ChatGPT in translational research | Efficiency in writing; analysis of large datasets (e.g., electronic health records or genomic data); predict risk factors for disease; predict disease outcomes | Compromised quality of data available; inability to understand the complexity of biologic systems | ChatGPT use in scientific and medical journals is inevitable in near future |

| Patel and Lam [53] | A commentary on ChatGPT utility in documentation of discharge summary | ChatGPT can help to reduce the burden of discharge summaries providing high-quality and efficient output | Data governance issues; risk of depersonalization of care; risk of incorrect or inadequate information | Proactive adoption of ChatGPT is needed to limit any possible future issues and limitations |

| Zhavoronkov * [54] | A perspective reporting a conversation with ChatGPT about rapamycin use from a philosophical perspective | ChatGPT provided correct summary of rapamycin side effects; it referred to the need to consult a health care provider based on the specific situation | - | Demonstration of ChatGPT’s potential to generate complex philosophical arguments |

| Hallsworth et al. [55] | A comprehensive opinion article submitted before ChatGPT launching on the value of theory-based research | It can help to circumvent language barriers; it can robustly help to process massive data in short time; it can stimulate creativity by humans if “AI in the Loop: Humans in Charge” is applied | Ethical issues; legal responsibility issues; lack of empathy and personal communication; lack of transparency | Despite the AI potential in science, there is an intrinsic value of human engagement in the scientific process which cannot be replaced by AI contribution |

| Stokel-Walker and Van Noorden [14] | Nature news feature article on ChatGPT implications in science | More productivity among researchers | Problems in reliability and factual inaccuracies; misleading information that seem plausible (hallucination); over-detailed content; risk of bias; ethical issues; copyright issues | “AI in the Loop: Humans in Charge” should be used; ChatGPT widespread use in the near future would be inevitable |

| Huh [56] | A study to compare ChatGPT performance on a parasitology exam to the performance of Korean medical students | ChatGPT performance will improve by deep learning | ChatGPT performance was lower compared to medical students; plausible explanations for incorrect answers (hallucination) | ChatGPT performance will continue to improve, and health care educators/students are advised to incorporate this tool into the educational process |

| Khan et al. [57] | A communication on ChatGPT use in medical education and clinical management | ChatGPT can help in automated scoring; assistance in teaching; improved personalized learning; assistance in research; generation of clinical vignettes; rapid access to information; translation; documentation in clinical practice; support in clinical decisions; personalized medicine | Lack of human-like understanding; the limited knowledge up to 2021 | ChatGPT is helpful in medical education, research, and in clinical practice; however, the human capabilities are still needed |

| Gilson et al. [58] | An article on the performance of ChatGPT on USMLE 3 | Ability to understand context and to complete a coherent and relevant conversation in the medical field; can be used as an adjunct in group learning | The limited knowledge up to 2021 | ChatGPT passes the USMLE with performance at a 3rd year medical student level; can help to facilitate learning as a virtual medical tutor |

| Kung et al. [59] | An article showing the ChatGPT raised accuracy which enabled passing the USMLE | Accuracy with high concordance and insight; it can facilitate patient communication; improved personalized medicine | - | ChatGPT has a promising potential in medical education; future studies are recommended to consider non-biased approach with quantitative natural language processing and text mining tools such as word network analysis |

| Marchandot et al. [60] | A commentary on ChatGPT use in academic writing | ChatGPT can assist in literature review saving time; the ability to summarize papers; the ability to improve language | Risk of inaccurate content; risk of bias; ChatGPT may lead to decreased critical thinking and creativity in science; ethical concerns; risk of plagiarism | ChatGPT can be listed as an author based on its significant contribution |

| Author(s) [Record] | Design, Aims | Applications, Benefits | Risks, Concerns, Limitations | Suggested Action, Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [61] | An arXiv preprint 1; investigating ChatGPT effectiveness to generate Boolean queries for systematic literature reviews | Higher precision compared to the current automatic query formulation methods | Non-suitability for high-recall retrieval; many incorrect MeSH 11 terms; variability in query effectiveness across multiple requests; a black-box application | A promising tool for research |

| Borji [20] | An arXiv preprint; to highlight the limitations of ChatGPT | Extremely helpful in scientific writing | Problems in spatial, temporal, physical, psychological and logical reasoning; limited capability to calculate mathematical expressions; factual errors; risk of bias and discrimination; difficulty in using idioms; lack of real emotions and thoughts; no perspective for the subject; over-detailed; lacks human-like divergences; lack of transparency and reliability; security concerns with vulnerability to data poisoning; violation of data privacy; plagiarism; impact on the environment and climate; ethical and social consequences | Implementation of responsible use and precautions; proper monitoring; transparent communication; regular inspection for biases, misinformation, among other harmful purposes (e.g., identity theft) |

| Cotton et al. [62] | An EdArXiv 2 preprint on the academic integrity in ChatGPT era | - | Risk of plagiarism; academic dishonesty | Careful thinking of educational assessment tools |

| Gao et al. [63] | A bioRxiv 3 preprint comparing the scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to original abstracts | A tool to decrease the burden of writing and formatting; it can help to overcome language barriers | Misuse to falsify research; risk of bias | The use of ChatGPT in scientific writing or assistance should be clearly disclosed and documented |

| Polonsky and Rotman [64] | An SSRN 4 preprint on listing ChatGPT as an author | ChatGPT can help to accelerate the research process; it can help to increase accuracy and precision | Intellectual property issues if financial gains are expected | AI 12 can be listed as an author in some instances |

| Aczel and Wagenmakers [65] | A PsyArXiv 5 preprint as a guide of transparent ChatGPT use in scientific writing | - | Issues of originality, transparency issues | There is a need to provide sufficient information on ChatGPT use, with accreditation and verification of its use |

| De Angelis et al. [66] | An SSRN preprint discussing the concerns of an AI-driven infodemic | ChatGPT can support and expedite academic research | Generation of misinformation and the risk of subsequent infodemics; falsified or fake research; ethical concerns | Carefully weigh ChatGPT possible benefits with its possible risks; there is a need to establish ethical guidelines for ChatGPT use; a science-driven debate is needed to address ChatGPT utility |

| Benoit [67] | A medRxiv 6 preprint on the generation, revision, and evaluation of clinical vignettes as a tool in health education using ChatGPT | Consistency, rapidity and flexibility of text and style; ability to generate plagiarism-free text | Clinical vignettes’ ownership issues; inaccurate or non-existent references | ChatGPT can allow for improved medical education and better patient communication |

| Sharma and Thakur [68] | A ChemRxiv 7 preprint on ChatGPT possible use in drug discovery | ChatGPT can help to identify and validate new drug targets; to design new drugs; to optimize drug properties; to assess toxicity; and to generate drug-related reports | Risk of bias or inaccuracies; inability to understand the complexity of biologic systems; transparency issues; lack of experimental validation; limited interpretability; limited handling of uncertainty; ethical issues | ChatGPT can be a powerful and promising tool in drug discovery; however, its accompanying ethical issues should be addressed |

| Rao et al. [69] | A medRxiv preprint on the usefulness of ChatGPT in radiologic decision making | ChatGPT showed moderate accuracy to determine appropriate imaging steps in breast cancer screening and evaluation of breast pain | Lack of references; alignment with user intent; inaccurate information; over-detailed; recommending imaging in futile situations; providing rationale for incorrect imaging decisions; the black box nature with lack of transparency | Using ChatGPT for radiologic decision making is feasible, potentially improving the clinical workflow and responsible use of radiology services |

| Antaki et al. [70] | A medRxiv preprint assessing ChatGPT’s ability to answer a diverse MCQ 8 exam in ophthalmology | ChatGPT currently performs at the level of an average first-year ophthalmology resident | Inability to process images; risk of bias; dependence on training dataset quality | There is a potential of ChatGPT use in ophthalmology; however, its applications should be carefully addressed |

| Aydın and Karaarslan [71] | An SSRN preprint on the use of ChatGPT to conduct a literature review on digital twin in health care | Low risk of plagiarism; accelerated literature review; more free time for researchers | Lack of originality | Expression of knowledge can be accelerated using ChatGPT; further work will use ChatGPT in citation analysis to assess the attitude towards the findings |

| Sanmarchi et al. [72] | A medRxiv preprint evaluating ChatGPT value in an epidemiologic study following the STROBE 9 recommendations | ChatGPT can provide appropriate responses if proper constructs are developed; more free time for researchers to focus on experimental phase | Risk of bias in the training data; risk of devaluation of human expertise; risk of scientific fraud; legal issues; reproducibility issues | Despite ChatGPT possible value, the research premise and originality will remain the function of human brain |

| Duong and Solomon [73] | A medRxiv preprint evaluating ChatGPT versus human responses to questions on genetics | Generation of rapid and accurate responses; easily accessible information for the patients with genetic disease and their families; it can help can health professionals in the diagnosis and treatment of genetic diseases; it could make genetic information widely available and help non-experts to understand such information | Plausible explanations for incorrect answers (hallucination); reproducibility issues | The value of ChatGPT will increase in research and clinical settings |

| Yeo et al. [74] | A medRxiv preprint evaluating ChatGPT responses to questions on cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma | Improved health literacy with better patient outcome; free availability; increased efficiency among health providers; emulation of empathetic responses | Non-comprehensive responses; the limited knowledge up to 2021; responses can be limited and not tailored to specific country or region; legal issues | ChatGPT may serve as a useful aid for patients besides the standard of care; future studies on ChatGPT utility are recommended |

| Bašić et al. [75] | An arXiv preprint on the performance of ChatGPT in essay writing compared to masters forensic students in Croatia | - | Risk of plagiarism; lack of originality; ChatGPT use did not accelerate essay writing | The concerns in the academia towards ChatGPT are not totally justified; ChatGPT text detectors can fail |

| Hisan and Amri [76] | An RG 10 preprint on ChatGPT use medical education | Generation of educational content; useful to learn languages | Ethical concerns; scientific fraud (papermills); inaccurate responses; declining quality of educations with the issues of cheating | Appropriate medical exam design is needed, especially for practical skills |

| Jeblick et al. [77] | An arXiv preprint on ChatGPT utility to simplify and summarize radiology reports | Generation of medical information relevant for the patients; moving towards patient-centered care; cost efficiency | Bias and fairness issues; misinterpretation of medical terms; imprecise responses; odd language; hallucination (plausible yet inaccurate response); unspecific location of injury/disease | Demonstration of the ability of ChatGPT simplified radiology reports; however, the limitations should be considered. Improvements of patient-centered care in radiology could be achieved via ChatGPT use |

| Nisar and Aslam [78] | An SSRN preprint on the assessment of ChatGPT usefulness to study pharmacology | Good accuracy | Content was not sufficient for research purposes | ChatGPT can be a helpful self-learning tool |

| Lin [79] | A PsyArXiv preprint to describe ChatGPT’s utility in academic education | Versatility | Hallucination (inaccurate information that sounds scientifically plausible); fraudulent research; risk of plagiarism; copyright issues | ChatGPT has a transformative long-term potential; embrace ChatGPT and use it to augment human capabilities; however, adequate guidelines and codes of conduct are urgently needed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060887

Sallam M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare. 2023; 11(6):887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060887

Chicago/Turabian StyleSallam, Malik. 2023. "ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns" Healthcare 11, no. 6: 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060887

APA StyleSallam, M. (2023). ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare, 11(6), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060887