The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Peritoneal Dialysis Patients at a Second-Level Hospital in Yucatán Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

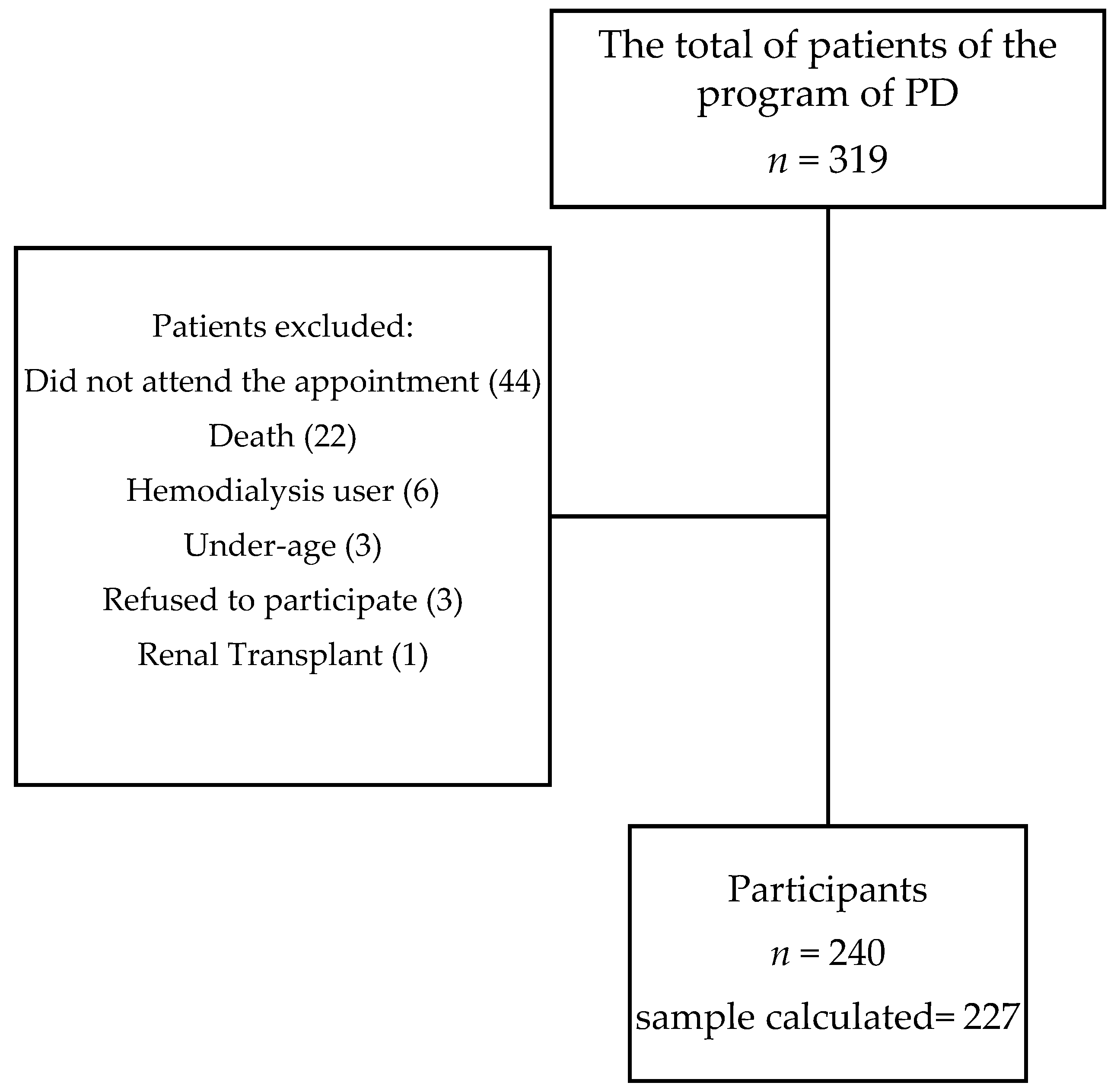

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Research Instrument

2.5. Clinical Characteristics and Biochemical Parameters of Patients

2.6. Ethics

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Use of CAM

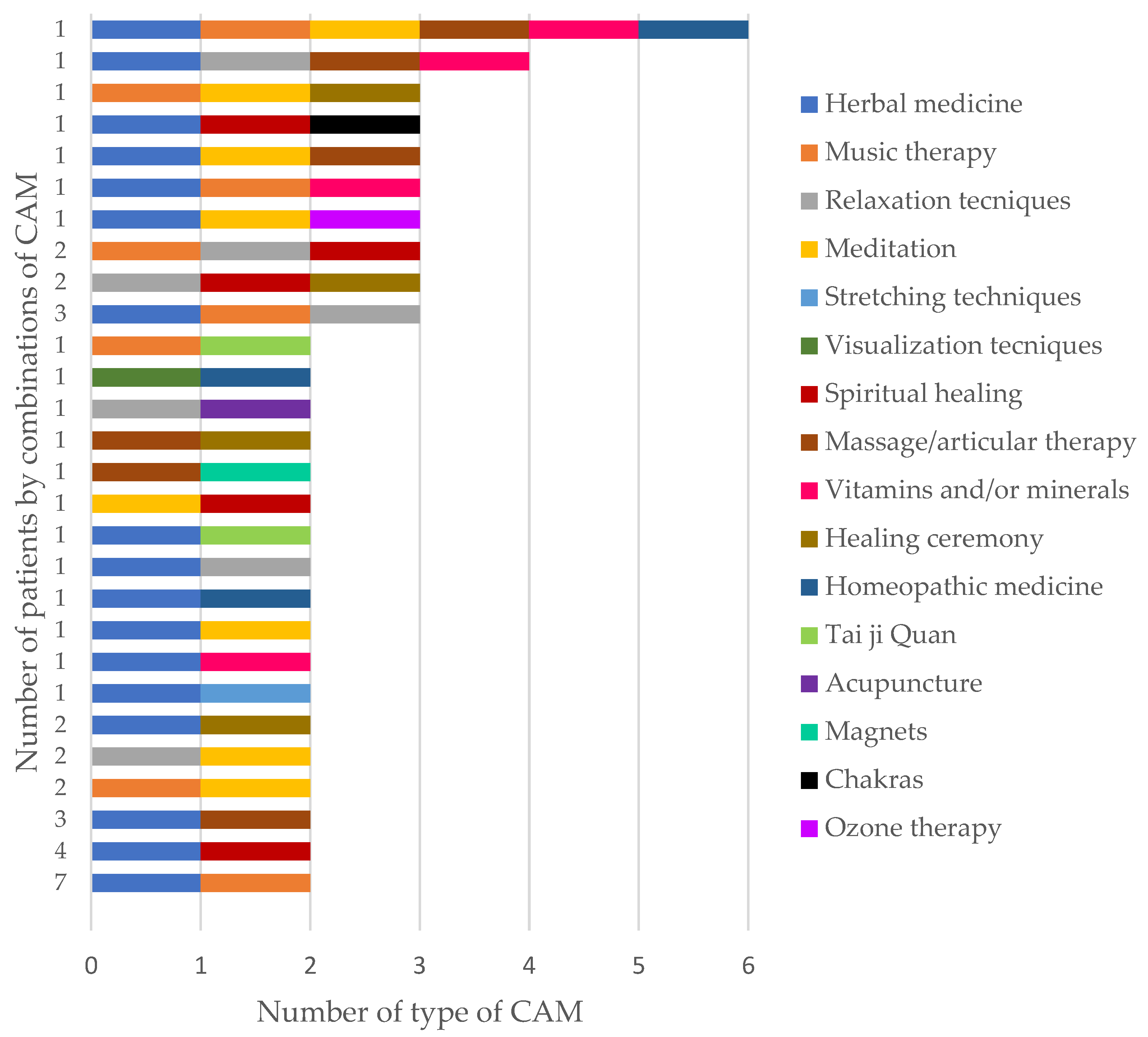

3.2. Type of CAM

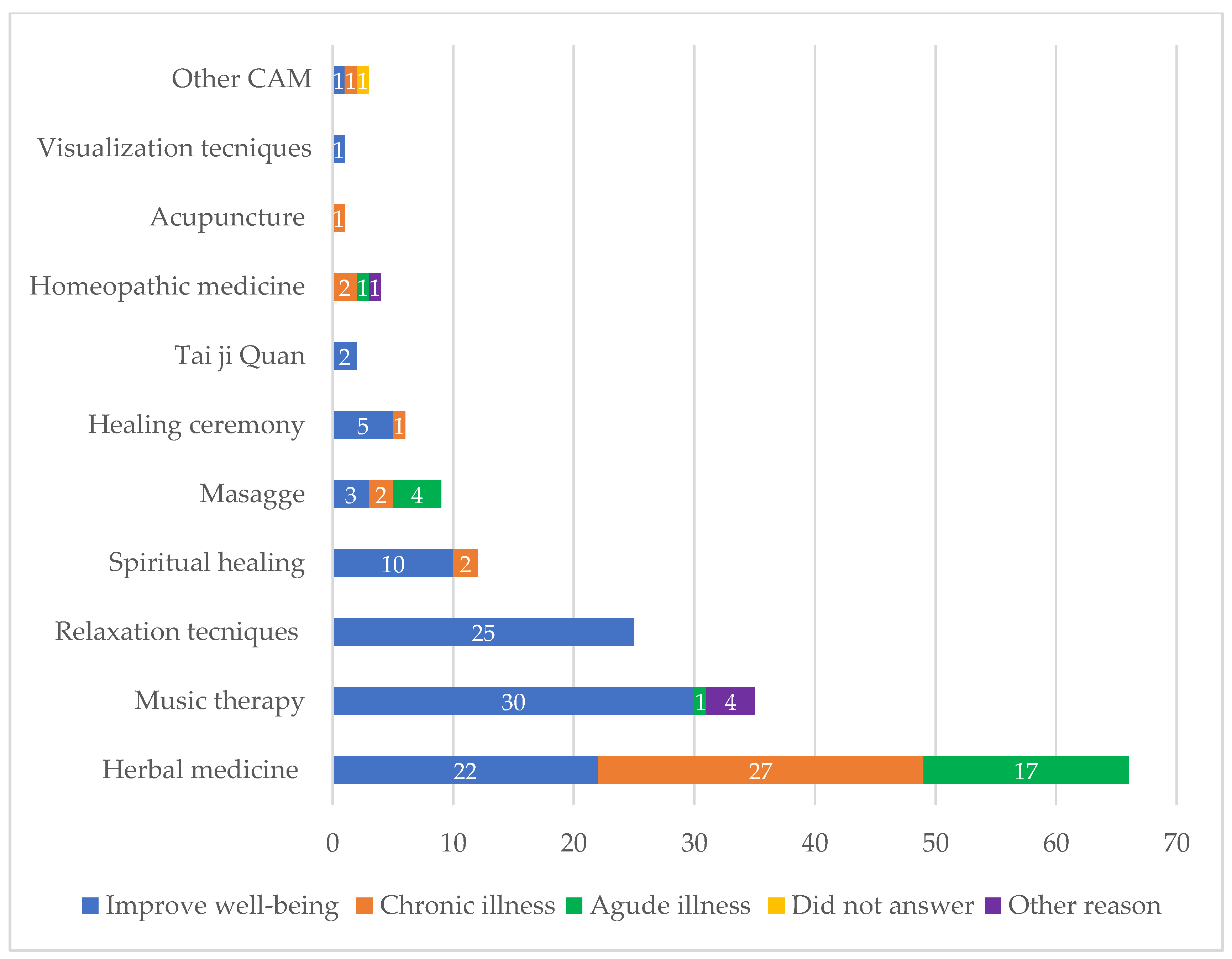

3.3. Reason to Use CAM

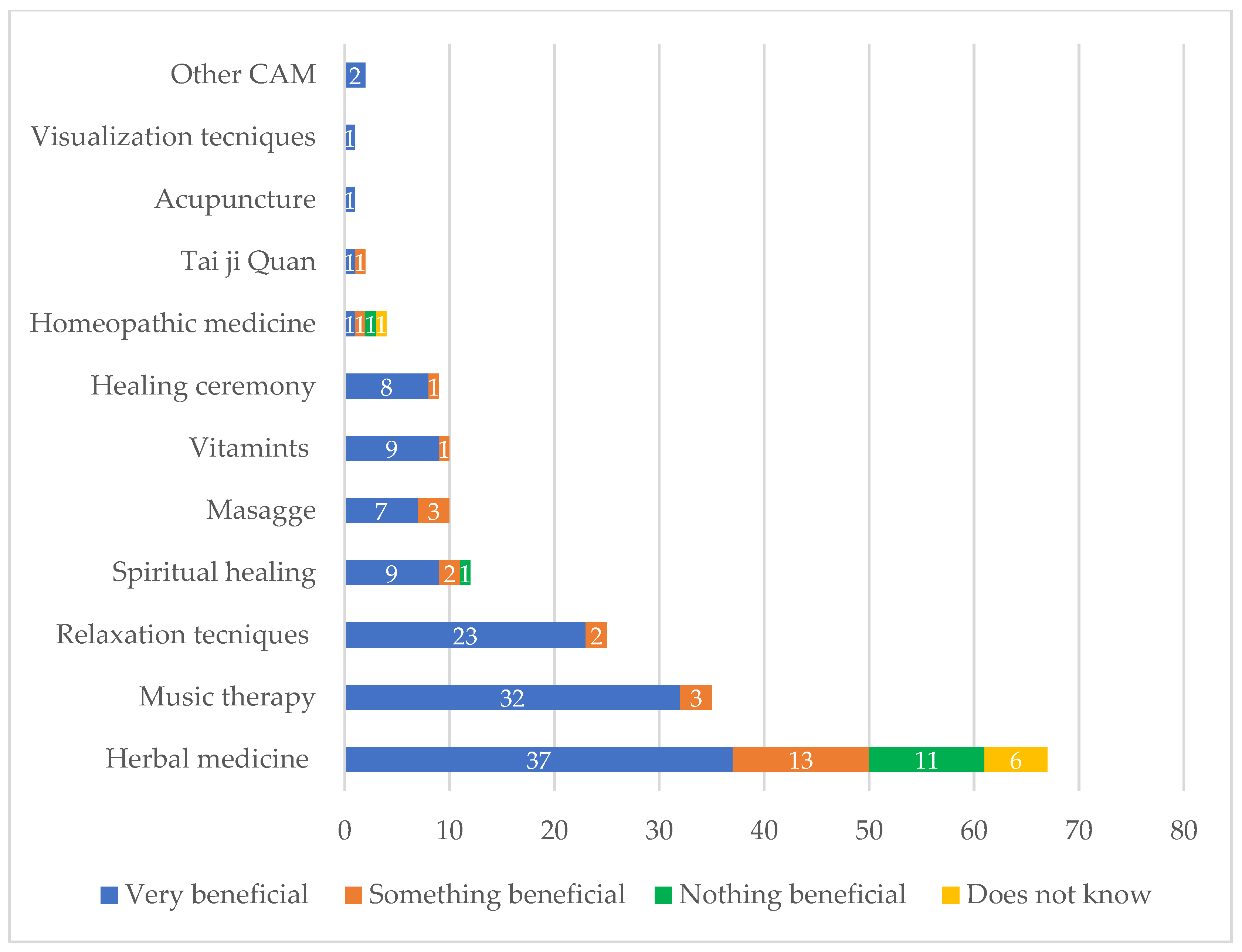

3.4. Perception of Benefit of Using CAM

3.5. Adverse Effects and Starting Time of CAM Use

3.6. Recommending the Use of CAM

3.7. Inform the Use of CAM to Medical Doctor

3.8. Clinical Characteristics and Biochemical Parameters of Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cockwell, P.; Fisher, L.A. The global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2020, 395, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. PAHO. The Burden of Kidney Diseases. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/enlace/burden-kidney-diseases#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20kidney%20diseases%20are,of%20increase%20in%20the%20Region (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: An update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez-Jimenez, E.; Madero, M. Global dialysis perspective: Mexico. Kidney360 2020, 1, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health. Salud Complementaria, Alternativa O Integral: ¿Qué Hay Detrás De Estos Nombres? Available online: https://nccih.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/Whats_In_A_Name_SPANISH_05-16-2015.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Youn, B.-Y.; Moon, S.; Mok, K.; Cheon, C.; Ko, Y.; Park, S.; Jang, B.-H.; Shin, Y.C.; Ko, S.-G. Use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine in nine countries: A cross-sectional multinational survey. Complement Ther. Med. 2022, 71, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangkiatkumjai, M.; Boardman, H.; Walker, D.-M. Potential factors that influence usage of complementary and alternative medicine worldwide: A systematic review. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abheiden, H.; Teut, M.; Berghöfer, A. Predictors of the use and approval of CAM: Results from the German General Social Survey (ALLBUS). BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal Aslan, K.S. Investigation of the effects of complementary and alternative therapy usage on physical activity and self-care in individuals diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 36, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Daikuhara, H.; Oshima, T.; Suzuki, H.; Okada, S.; Miyatake, N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine and its relationship with health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Epidemiologia 2023, 4, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.Y.; Verma, K.D.; Gilotra, K. Quantity and quality of complementary and alternative medicine recommendations in clinical practice guidelines for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 3004–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palileo-Villanueva, L.M.; Palafox, B.; Amit, A.M.L.; Pepito, V.C.F.; Ab-Majid, F.; Ariffin, F.; Balabanova, D.; Isa, M.-R.; Mat-Nasir, N.; My, M.; et al. Prevalence, determinants and outcomes of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use for hypertension among low-income households in Malaysia and the Philippines. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, N.M.; Devansyah, S.; Modjaningrat, I.; Suryawan, N.; Susanah, S.; Rakhmillah, L.; Wahyudi, K.; Kaspers, G.J.L. Type of cancer and complementary and alternative medicine are determinant factors for the patient delay experienced by children with cancer: A study in West Java, Indonesia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70, e30192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, C.-Y.; Lee, B.; Lee, B.-J.; Kim, K.-I.; Jung, H.-J. Herbal medicine compared to placebo for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 717570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gözcü, E.; Çakmak, İ.; Öz, B.; Karataş, A.; Akar, Z.A.; Koca, S.S. Complementary alternative medicine in rheumatic diseases: Causes, choices, and outcomes according to patients. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 2022, 9, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprzycka, K.; Kurzawa, M.; Kucharz, M.; Godawska, M.; Oleksa, M.; Stawowy, M.; Slupinska-Borowka, K.; Sznek, W.; Gisterek, I.; Boratyn-Nowicka, A.; et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in hospitalized cancer patients-study from Silesia, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthi, E.; Diezi, M.; Danon, N.; Dubois, J.; Pasquier, J.; Burnand, B.; Rodondi, P.-Y. Complementary and alternative medicine use by pediatric oncology patients before, during, and after treatment. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Ortiz, D.; Contreras-Yáñez, I.; Cáceres-Giles, C.; Ballinas-Sánchez, Á.; Valverde-Hernández, S.; Merayo-Chalico, F.; Fernández-Ávila, D.; Londoño, J.; Pascual-Ramos, V. Association between physician-patient relationship and the use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rev. Colomb. De Reumatol. 2021, 28, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Sánchez, R.; Tostado-Fernández, F.A. Prevalence of use of alternative and complementary medicine in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Rev. Gastroenterol. Mex. 2005, 70, 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Arellano, A.; Jaime-Delgado, M.; Herrera-Alvarez, S.; Oaxaca-Navarro, J.; Salazar-Martínez, E. The alternative medicine used as complementary in patients positive for HIV. Rev. Med. Del Inst. Mex. Del Seguro Soc. 2009, 47, 651–658. [Google Scholar]

- Yam Sosa, B.; Quiñones, M.; Pérez Aguilar, E. La Medicina Tradicional Entre Los Henequeneros Y Maiceros Yucatecos, 1st ed.; Dirección General de Culturas Populares: Mérida, Yuc, Mexico, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Berretta, M.; Rinaldi, L.; Taibi, R.; Tralongo, P.; Fulvi, A.; Montesarchio, V.; Madeddu, G.; Magistri, P.; Bimonte, S.; Trovò, M.; et al. Physician attitudes and perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): A multicentre italian study. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeeb, A.A.; King, S.M.; Olaku, O.; White, J.D. Communication between cancer patients and physicians about complementary and alternative medicine: A systematic review. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2023, 29, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.J.; Pittman, S.; Govil, A.; Sorn, L.; Bissler, G.; Schultz, T.; Faith, J.; Kant, S.; Roy-Chaudhury, P. Alternative medicine use in dialysis patients: Potential for good and bad! Nephron Clin. Pract. 2007, 105, c108–c113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quandt, S.A.; Ip, E.H.; Saldana, S.; Arcury, T.A. Comparing two questionnaires for eliciting CAM use in a multi-ethnic US population of older adults. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2012, 4, e205–e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban, S.; Vázquez Peña, F.; Terrasa, S. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of a standardized international questionnaire on use of alternative and complementary medicine (I-CAM-Q) for Argentina. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312342/9789241515436-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Nowack, R.; Balle, C.; Birnkammer, F.; Koch, W.; Sessler, R.; Birck, R. Complementary and alternative medications consumed by renal patients in southern. J. Ren. Nutr. 2009, 19, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzdil, N.; Kılıç, Z. Health literacy and attitudes to holistic, complementary and alternative medicine in peritoneal dialysis patients: A descriptive study. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2022, 55, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.S.M.A.; Phaneendra, D.; Pavani, C.D.; Soundararajan, P.; Rani, N.V.; Thennarasu, P.; Kannan, G. Usage of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with chronic kidney disease on maintenance hemodialysis. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2016, 8, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ndao-Brumblay, S.K.; Green, C.R. Predictors of complementary and alternative medicine use in chronic pain patients. Pain Med. 2010, 11, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.A.; Hassanein, S.M.; Leil, M.M.; NasrAllah, M.M. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney transplant recipients. J. Ren. Nutr. 2015, 25, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelino, L.R.; Nayak-Rao, S.; Pradeep Shenoy, M. Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine in chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional single-center study from south. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 2018, 29, 1017–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Alanizy, L.; Almatham, K.; Al Basheer, A.; Al Fayyad, I. Complementary and alternative medicine practice among saudi patients with chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2020, 13, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolla, C. La medicina tradicional indígena en el México actual. Arqueol. Mex. 2005, 13, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan, M.; Namjoo, Z.; Bahrami, A.; Tajedini, H.; Shamsaddini-lori, Z.; Zarei, A.; Dehghani, M.; Ranjbar, M.; Ra, F.; Nasab, S. The use of complementary and alternative medicines, and quality of life in patients under hemodialysis: A survey in southeast Iran. Complement Ther. Med. 2020, 51, 102431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, N.V.; Dang Xuan, T.; Teschke, R. Potential hepatotoxins found in herbal medicinal products: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, R.; Ying, J.; Zhao, M.; Wu, X.; Cao, G.; Wang, K. Nephrotoxicity of Herbal Medicine and Its Prevention. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 569551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touiti, N.; Houssaini, T.S.; Achour, S. Overview on pharmacovigilance of nephrotoxic herbal medicines used worldwide. Clin. Phytoscience 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, T.; Rahman, M.A.; Moni, A.; Apu, M.A.I.; Fariha, A.; Hannan, M.A.; Uddin, M.J. Prospects for protective potential of Moringa oleifera against kidney diseases. Plants 2021, 10, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health. Chamomile. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/chamomile#:~:text=Sideeffectsareuncommonand,intocontactwithchamomileproducts (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Parvez, M.K.; Rishi, V. Herb-drug interactions and hepatotoxicity. Curr. Drug Metab. 2019, 20, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, S.F.; Alzahrani, A.; Alghamdy, Z.; Alnajar, D.; Alsubhi, N.; Khan, A.; Ahmed, M.E. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in the general public of western saudi arabia: A cross-sectional survey. Cureus 2022, 14, e32784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; McCulloch, C.E.; Iribarren, C.; Darbinian, J.; Go, A.S. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.B.W.; Charn, T.C.; Chew, Z.H.; Ng, T.P. Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with chronic diseases in primary care is associated with perceived quality of care and cultural beliefs. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | CAM Users | CAM Non-Users | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 65 (27.1) | 64 (26.7) | 129 (53.8) | 0.122 |

| Male | 67 (27.9) | 44 (18.3) | 111 (46.3) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Employed | 4 (1.7) | 6 (2.5) | 10 (4.2) | 0.210 |

| Housewife | 49 (20.4) | 39 (16.3) | 88 (36.7) | |

| Professional | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Retired | 42 (17.5) | 27 (11.3) | 69 (28.8) | |

| Unemployed | 32 (13.3) | 33 (13.8) | 65 (27.1) | |

| Other | 5 (2.1) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (2.5) | |

| Education level | 0.174 | |||

| No formal education | 6 (2.5) | 14 (5.8) | 20 (8.3) | |

| Able to read and write | 5 (2.1) | 4 (1.7) | 9 (3.8) | |

| Primary education | 59 (24.6) | 50 (20.8) | 109 (45.4) | |

| Secondary education | 28 (11.7) | 17 (7.1) | 45 (18.8) | |

| High school | 21 (8.8) | 13 (5.4) | 34 (14.2) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13 (5.4) | 9 (3.8) | 22 (9.2) | |

| Higher | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Socioeconomical level | 0.857 | |||

| Low | 4 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) | 7 (2.9) | |

| Low high | 10 (4.2) | 10 (4.2) | 20 (8.3) | |

| Medium low | 51 (21.3) | 47 (19.6) | 98 (40.8) | |

| Medium | 53 (22.1) | 35 (14.6) | 88 (36.7) | |

| Medium high | 12 (5.0) | 12 (5.0) | 24 (10.0) | |

| High | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.3) |

| Type CAM | n = 132 (%) |

|---|---|

| Herbal medicine | 66 (50.0) |

| Mind-body practices | |

| Music therapy | 32 (24.2) |

| Relaxation techniques | 25 (18.9) |

| Meditation | 9 (6.8) |

| Stretching techniques | 3 (2.3) |

| Visualization techniques | 1 (0.8) |

| Spiritual healing | 12 (9.1) |

| Massage/articular therapy | 10 (7.6) |

| Vitamins and/or minerals | 10 (7.6) |

| Healing ceremony | 6 (4.5) |

| Homeopathic medicine | 4 (3.0) |

| Tai ji Quan | 2 (1.5) |

| Acupuncture | 1 (0.8) |

| Magnetic therapy | |

| Magnets | 1 (0.8) |

| Chakras | 1 (0.8) |

| Ozone therapy | 1 (0.8) |

| Type of Herbal Medicine | n = 97 (%) |

|---|---|

| Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) | 25 (25.8) |

| Moringa leaves (Moringa oleifera) | 15 (15.5) |

| Chaya leaves (Cnidoscolus aconitifolius) | 8 (8.2) |

| Orange leaves (Citrus aurantium) | 6 (6.2) |

| Linden (Tilia mexicana) | 4 (4.1) |

| Azhar (Orange blossom) | 2 (2.1) |

| Noni fruit (Morinda citrifolia) | 2 (2.1) |

| Neem (Azadirachta indica) | 2 (2.1) |

| Lemon (Citrus limon) | 2 (2.1) |

| Riñonina (Ipomoea pes-caprae) | 2 (2.1) |

| Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) | 2 (2.1) |

| Oregano (Plectranthus amboinicus) | 2 (2.1) |

| Rue (Ruta chalepensis) | 2 (2.1) |

| Blue agave (Agave tequilana) | 1 (1.0) |

| Belladonna (Kalanchoe integra) | 1 (1.0) |

| Bougainvillea (Bougainvillea glabra) | 1 (1.0) |

| Espada de cristo (Dracaena trifasciata) | 1 (1.0) |

| Peppermint (Mentha x piperita) | 1 (1.0) |

| Hibiscus flower (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis) | 1 (1.0) |

| Laurel (Ficus benjamina) | 1 (1.0) |

| Cow tongue (Dracaena trifasciata) | 1 (1.0) |

| Blue berry (Vaccinium corymbosum) | 1 (1.0) |

| Cucumber cat (Parmenteria aculata) | 1 (1.0) |

| Beetroot (Beta vulgaris) | 1 (1.0) |

| Sabila (Aloe vera) | 1 (1.0) |

| Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) | 1 (1.0) |

| Unknown tincture | 1 (1.0) |

| Acacia (Acacia cornigera) | 1 (1.0) |

| Aloe (Aloe vera) | 1 (1.0) |

| Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) | 1 (1.0) |

| Coconut (Cocos nucifera) | 1 (1.0) |

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa Yucateca) | 1 (1.0) |

| Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) | 1 (1.0) |

| Basil (Ocimum basilicum) | 1 (1.0) |

| Añil (Indigofera tinctoria) | 1 (1.0) |

| Chia (Salvia hispanica) | 1 (1.0) |

| Variables | CAM Users | CAM Non-Users | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Body mass index | 0.816 | |||

| Underweight | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.3) | |

| Normal | 37 (15.4) | 31 (12.9) | 68 (28.3) | |

| Overweight | 54 (22.5) | 52 (21.7) | 106 (44.2) | |

| Obesity type 1 | 28 (11.7) | 18 (7.5) | 46 (19.2) | |

| Obesity type 2 | 8 (3.3) | 4 (1.7) | 12 (5.0) | |

| Obesity type 3 | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | |

| Edema grade | 0.370 | |||

| Without edema | 45 (18.8) | 45 (18.8) | 90 (37.5) | |

| Grade 1 | 38 (15.8) | 35 (14.6) | 73 (30.4) | |

| Grade 2 | 33 (13.8) | 17 (7.1) | 50 (20.8) | |

| Grade 3 | 13 (5.4) | 10 (4.2) | 23 (9.6) | |

| Grade 4 | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Nutritional status | 0.422 | |||

| With malnutrition | 33 (13.8) | 32 (13.3) | 65 (27.1) | |

| Without malnutrition | 99 (41.3) | 76 (31.7) | 175 (72.9) | |

| Karnosfsky index | 0.977 | |||

| 100 | 15 (6.3) | 9 (3.8) | 24 (10.0) | |

| 90 | 37 (15.4) | 31 (12.9) | 68 (28.3) | |

| 80 | 27 (11.3) | 25 (10.4) | 52 (21.7) | |

| 70 | 25 (10.4) | 20 (8.3) | 45 (18.8) | |

| 60 | 15 (6.3) | 13 (5.4) | 28 (11.7) | |

| 50 | 13 (5.4) | 10 (4.2) | 23 (9.6) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis type | 0.264 | |||

| CAPD | 74 (30.8) | 59 (24.6) | 133 (55.4) | |

| APD | 38 (15.8) | 39 (16.3) | 77 (32.1) | |

| IPD | 20 (8.3) | 10 (4.2) | 30 (12.5) | |

| Etiology of CKD | 0.334 | |||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 84 (35) | 66 (27.5) | 150 (62.5) | |

| Nephroangiosclerosis | 14 (5.8) | 10 (4.2) | 24 (10.0) | |

| Lithiasis | 16 (6.7) | 8 (3.3) | 24 (10.0) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | |

| Lupus | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.3) | |

| No determination | 6 (2.5) | 14 (5.8) | 20 (8.3) | |

| Other | 7 (2.9) | 6 (2.5) | 13 (5.4) | |

| Renal transplantation protocol | 0.410 | |||

| Yes, living donor | 6 (2.5) | 2 (0.8) | 8 (3.3) | |

| Yes, deceased donor | 27 (11.3) | 19 (7.9) | 46 (19.2) | |

| No | 94 (39.2) | 87 (36.3) | 181 (75.4) | |

| Variables | CAM Users | CAM Non-Users | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Minimum | Maximum | ±SD | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | ±SD | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.2 | 7 | 15 | 1.6 | 10 | 6 | 16.9 | 2 | 0.841 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 130.1 | 42 | 302 | 46.9 | 128 | 13 | 336 | 55.4 | 0.814 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 10.2 | 2.8 | 22.7 | 4 | 10.4 | 1.2 | 26.8 | 4.49 | 0.996 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 125.5 | 9.4 | 398 | 65 | 122 | 47 | 328 | 48.8 | 0.615 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.5 | 2.4 | 12.7 | 1.5 | 6.9 | 2.8 | 11.5 | 1.63 | 0.094 |

| Albumin (gr/dL) | 3.3 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 4.9 | 0.59 | 0.558 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.8 | 6.9 | 11.4 | 0.7 | 8.9 | 7 | 11.6 | 0.76 | 0.715 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 5.4 | 2 | 11.4 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 11.5 | 1.9 | 0.729 |

| Potassium (mg/dL) | 4.3 | 2.8 | 7.2 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 6.8 | 0.7 | 0.227 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 134 | 100 | 220 | 19.8 | 133 | 90 | 200 | 17.9 | 0.525 |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 82 | 50 | 130 | 11.1 | 78.4 | 60 | 100 | 9.7 | 0.005 * |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3.0 | 2.0 | 7 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 2 | 6 | 0.98 | 0.519 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gracida-Osorno, C.; Jiménez-Martínez, S.L.; Uc-Cachón, A.H.; Molina-Salinas, G.M. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Peritoneal Dialysis Patients at a Second-Level Hospital in Yucatán Mexico. Healthcare 2023, 11, 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050722

Gracida-Osorno C, Jiménez-Martínez SL, Uc-Cachón AH, Molina-Salinas GM. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Peritoneal Dialysis Patients at a Second-Level Hospital in Yucatán Mexico. Healthcare. 2023; 11(5):722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050722

Chicago/Turabian StyleGracida-Osorno, Carlos, Sandra Luz Jiménez-Martínez, Andrés Humberto Uc-Cachón, and Gloria María Molina-Salinas. 2023. "The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Peritoneal Dialysis Patients at a Second-Level Hospital in Yucatán Mexico" Healthcare 11, no. 5: 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050722

APA StyleGracida-Osorno, C., Jiménez-Martínez, S. L., Uc-Cachón, A. H., & Molina-Salinas, G. M. (2023). The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Peritoneal Dialysis Patients at a Second-Level Hospital in Yucatán Mexico. Healthcare, 11(5), 722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050722