The Intersection of Health Rehabilitation Services with Quality of Life in Saudi Arabia: Current Status and Future Needs

Abstract

1. Background

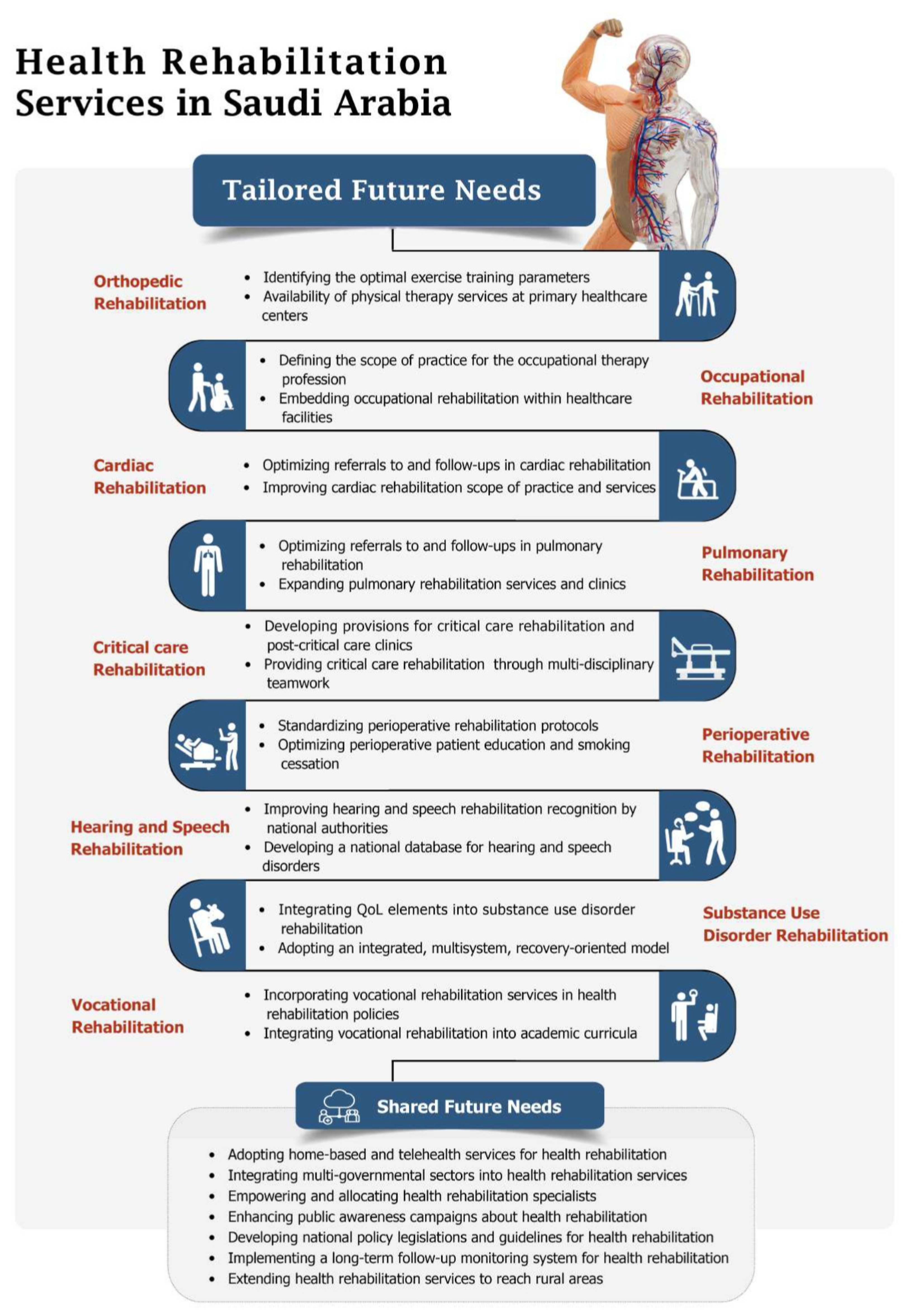

2. Orthopedic Rehabilitation

2.1. Current Status

2.2. Future Needs

3. Occupational Rehabilitation

3.1. Current Status

3.2. Future Needs

4. Cardiac Rehabilitation

4.1. Current Status

4.2. Future Needs

5. Pulmonary Rehabilitation

5.1. Current Status

5.2. Future Needs

6. Critical Care Rehabilitation

6.1. Current Status

6.2. Future Needs

7. Perioperative Rehabilitation

7.1. Current Status

7.2. Future Needs

8. Hearing and Speech Rehabilitation

8.1. Current Status

8.2. Future Needs

9. Substance Use Disorder Rehabilitation

9.1. Current Status

9.2. Future Needs

10. Vocational Rehabilitation

10.1. Current Status

10.2. Future Needs

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quality of Life Program. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/qol/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Health Sector Transformation Strategy. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/vro/Pages/Health-Transformation-Strategy.aspx (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Porter, M.E. What is value in health care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborators GBDSA. The burden of disease in Saudi Arabia 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Planet Health 2020, 4, e195–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, J.S. Prevalence, incidence, morbidity and mortality rates of COPD in Saudi Arabia: Trends in burden of COPD from 1990 to 2019. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajian-Tilaki, K.; Heidari, B.; Hajian-Tilaki, A. Are gender differences in health-related quality of life attributable to sociodemographic characteristics and chronic disease conditions in elderly people? Int. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 8, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Glinac, A.; Matovic, L.; Saric, E.; Bratovcic, V.; Sinanovic, S. The quality of life in chronic patients in the process of rehabilitation. Mater. Socio-Med. 2017, 29, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehle, L.P.; Phillips, K.M.; Bergmark, R.W.; Caradonna, D.S.; Gray, S.T.; Sedaghat, A.R. Symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis differentially impact general health-related quality of life. Rhinology 2016, 54, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellisé, F.; Vila-Casademunt, A.; Ferrer, M.; Domingo-Sàbat, M.; Bagó, J.; Pérez-Grueso, F.J.; Alanay, A.; Mannion, A.; Acaroglu, E. Impact on health related quality of life of adult spinal deformity (ASD) compared with other chronic conditions. Eur. Spine J. 2015, 24, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/index.htm#:~:text=Health%2Drelated%20quality%20of%20life%20(HRQOL)%20is%20an%20individual's,and%20mental%20health%20over%20time (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- De Groot, L.C.; Verheijden, M.W.; de Henauw, S.; Schroll, M.; van Staveren, W.A.; SENECA Investigators. Lifestyle, nutritional status, health, and mortality in elderly people across Europe: A review of the longitudinal results of the SENECA study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2004, 59, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleisa, E.; Al-Sobayel, H.; Buragadda, S.; Rao, G. Rehabilitation services in Saudi Arabia: An overview of its current structure and future challenges. J. Gen. Pract. 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fani Marvasti, F.; Stafford, R.S. From “Sick Care” to Health Care: Reengineering Prevention into the U.S. System. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde, G.E.; Fonseca, A.C.; Boscoa, T.F.; Goncalves, M.R.; Bernardo, G.C.; Pianna, B.; Carnavale, B.F.; Gimenes, C.; Barrile, S.R.; Arca, E.A. Effect of aquatic physical therapy on pain perception, functional capacity and quality of life in older people with knee osteoarthritis: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.; Oldridge, N.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Rees, K.; Martin, N.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houchen-Wolloff, L.; Williams, J.E.; Green, R.H.; Woltmann, G.; Steiner, M.C.; Sewell, L.; Morgan, M.D.; Singh, S.J. Survival following pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: The effect of program completion and change in incremental shuttle walking test distance. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, R. The Privatization of Health Care System in Saudi Arabia. Health Serv. Insights 2020, 13, 1178632920934497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shammari, S.A.; Nass, M.; Al-Maatouq, M.A.; Al-Quaiz, J.M. Family practice in Saudi Arabia: Chronic morbidity and quality of care. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1996, 8, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diseases, G.B.D.; Injuries, C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Vollset, S.E.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Daoud, F.; Afshin, A.; Charara, R.; Khalil, I.; Higashi, H.; Abd El Razek, M.M. Burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990–2013: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, R.S.; Heywood, S.E.; Day, A.R. Aquatic physical therapy for hip and knee osteoarthritis: Results of a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 2007, 87, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P.; Lam, H.Y.; Ma, T.K.; Lo, C.N.; Mui, T.Y.; Tang, W.Y. Efficacy of physical therapy interventions on quality of life and upper quadrant pain severity in women with post-mastectomy pain syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 951–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74 (Suppl. 2), 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, M.A.; Richards, L.G. Promoting Health, Well-Being, and Quality of Life in Occupational Therapy: A Commitment to a Paradigm Shift for the Next 100 Years. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 71, 7104170010p1–7104170010p5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornblau, B.; Oliveira, D.; Mbiza, S. Measuring Quality of Life (QOL) Through Participation: A Synthesis of Multiple Qualitative Studies on Occupational Autonomy. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7411515356p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huri, M.; Huri, E.; Kayihan, H.; Altuntas, O. Effects of occupational therapy on quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. A randomized controlled study. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letts, L.; Edwards, M.; Berenyi, J.; Moros, K.; O’Neill, C.; O’Toole, C.; McGrath, C. Using occupations to improve quality of life, health and wellness, and client and caregiver satisfaction for people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 65, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, F.I. Functional evaluation: The Barthel index. Md. State Med. J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M.; Heinemann, A.W.; Wright, B.D.; Granger, C.V.; Hamilton, B.B. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1994, 75, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; McColl, M.; Opzoomer, A.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. The Canadian occupational performance measure: An outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 1990, 57, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, S.H. National Center for Developmental and Behavioral Disorders 2022. Available online: https://shc.gov.sa/Arabic/NCDBD/Pages/Vision.aspx (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Council, S.H. Namaai Application. Available online: https://shc.gov.sa/Arabic/NCDBD/Activities/Pages/namaee.aspx (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- McGarry, B.E.; White, E.M.; Resnik, L.J.; Rahman, M.; Grabowski, D.C. Medicare’s New Patient Driven Payment Model Resulted In Reductions In Therapy Staffing In Skilled Nursing Facilities: Study examines the effect of Medicare’s Patient Driven Payment Model on therapy and nursing staff hours at skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusynski, R.A.; Leland, N.E.; Frogner, B.K.; Leibbrand, C.; Mroz, T.M. Therapy staffing in skilled nursing facilities declined after implementation of the patient-driven payment model. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 2201–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maass, R.; Bonsaksen, T.; Gramstad, A.; Sveen, U.; Stigen, L.; Arntzen, C.; Horghagen, S. Factors associated with the establishment of new occupational therapist positions in Norwegian municipalities after the Coordination reform. Health Serv. Insights 2021, 14, 1178632921994908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Senani, F.; Salawati, M.; AlJohani, M.; Cuche, M.; Seguel Ravest, V.; Eggington, S. Workforce requirements for comprehensive ischaemic stroke care in a developing country: The case of Saudi Arabia. Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jadid, M.S. Disability in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2013, 34, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- AlHabib, K.F.; Elasfar, A.A.; AlBackr, H.; AlFaleh, H.; Hersi, A.; AlShaer, F.; Kashour, T.; AlNemer, K.; Hussein, G.A.; Mimish, L. Design and preliminary results of the heart function assessment registry trial in Saudi Arabia (HEARTS) in patients with acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.P.; AbuHaniyeh, A.; Ahmed, H. Cardiac Rehabilitation: Current Review of the Literature and Its Role in Patients with Heart Failure. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.; Harrison, A.; Doherty, P. The effectiveness of modern cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review of recent observational studies in non-attenders versus attenders. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, B.J.R.; Harrison, S.L.; Fazio-Eynullayeva, E.; Underhill, P.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Wright, D.J.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Lip, G.Y.H. Cardiac rehabilitation and all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure: A retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1704–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessler, J.; Bordoni, B. Cardiac Rehabilitation; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Price, K.J.; Gordon, B.A.; Bird, S.R.; Benson, A.C. A review of guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation exercise programmes: Is there an international consensus? Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 1715–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Dalal, H.M.; McDonagh, S.T.J. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in improving cardiovascular outcomes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M.; Theruvan, N.; Gad, A.; Shaheen, H.; Mosbah, S. Cardiac Rehabilitation: Future of Heart Health in Saudi Arabia, a Perceptual View. World J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 10, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, C.E.; Bevan-Smith, E.F.; Blakey, J.D.; Crowe, P.; Elkin, S.L.; Garrod, R.; Greening, N.J.; Heslop, K.; Hull, J.H.; Man, W.D.; et al. British Thoracic Society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adults. Thorax 2013, 68 (Suppl. 2), ii1–ii30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/ (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Gale, N.S.; Duckers, J.M.; Enright, S.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Shale, D.J.; Bolton, C.E. Does pulmonary rehabilitation address cardiovascular risk factors in patients with COPD? BMC Pulm. Med. 2011, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruit, M.A.; Singh, S.J.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Rochester, C.; Hill, K.; Holland, A.E.; Lareau, S.C.; Man, W.D.; et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, e13–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, A.; Rupley, L.; Meyers, K.; Johnson, K.; Eason, J. Outcomes in cardiopulmonary physical therapy: Chronic respiratory disease questionnaire (CRQ). Cardiopulm. Phys. Ther. J. 2008, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Quirk, F.; Baveystock, C. The St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir. Med. 1991, 85, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levack, W.M.; Watson, J.; Hay-Smith, E.J.C.; Davies, C.; Ingham, T.; Jones, B.; Cargo, M.; Houghton, C.; McCarthy, B. Factors influencing referral to and uptake and attendance of pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A qualitative evidence synthesis of the experiences of service users, their families, and healthcare providers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD013195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; Aldhahir, A.M. Current status of telehealth in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19. J. Fam. Community Med. 2020, 27, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Moamary, M. Impact of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme on respiratory parameters and health care utilization in patients with chronic lung diseases other than COPD. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012, 18, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhahir, A.M.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; Alqahtani, K.A.; Al Rajah, A.M.; Alkhathlan, B.S.; Singh, S.J.; Mandal, S.; Hurst, J.R. Pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD: A narrative review and call for further implementation in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2021, 16, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maliki, R.; Hawsawi, T.I.; Alrajab, F.I.; Alatawi, N.A.; Jamjoom, M.O.; Shakally, M.S.; Alzahrani, K.T. Saudi Physicians’ Awareness and Practice of Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Post-COVID-19 Syndrome Patients. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; Mahal, A.; Hill, C.J.; Lee, A.L.; Burge, A.T.; Cox, N.S.; Moore, R.; Nicolson, C.; O’Halloran, P.; Lahham, A. Home-based rehabilitation for COPD using minimal resources: A randomised, controlled equivalence trial. Thorax 2017, 72, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, S.M.; Rajah, A.M.A.; Aldabayan, Y.S.; Aldhahir, A.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; Alzahrani, A.A. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients’ Acceptance in E-Health Clinical Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, S.; Alqahtani, P. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: From Diagnosis to Treatment; Nova Science Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, N.K.; Fowler, R.A.; Bhagwanjee, S.; Rubenfeld, G.D. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 2010, 376, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, A.; Olafson, K.; Ramsey, C.D.; Yogendran, M.; Fransoo, R. Epidemiology of critically ill patients in intensive care units: A population-based observational study. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipping, C.J.; Harrold, M.; Holland, A.; Romero, L.; Nisbet, T.; Hodgson, C.L. The effects of active mobilisation and rehabilitation in ICU on mortality and function: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, M.D.; Nelliot, A.; Needham, D.M. Early mobilization and rehabilitation in the ICU: Moving back to the future. Respir. Care 2016, 61, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birtwistle, S.B.; Ashcroft, G.; Murphy, R.; Gee, I.; Poole, H.; Watson, P.M. Factors influencing patient uptake of an exercise referral scheme: A qualitative study. Health Educ. Res. 2019, 34, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawal, G.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, R. Post-intensive care syndrome: An overview. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2017, 5, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, O.; Edginton, T.; Casarin, A.; Vizcaychipi, M.P. The psychological and neurocognitive consequences of critical illness. A pragmatic review of current evidence. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2015, 16, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, D.M.; Davidson, J.; Cohen, H.; Hopkins, R.O.; Weinert, C.; Wunsch, H.; Zawistowski, C.; Bemis-Dougherty, A.; Berney, S.C.; Bienvenu, O.J. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, S.; Hatakeyama, J.; Kondo, Y.; Hifumi, T.; Sakuramoto, H.; Kawasaki, T.; Taito, S.; Nakamura, K.; Unoki, T.; Kawai, Y. Post-intensive care syndrome: Its pathophysiology, prevention, and future directions. Acute Med. Surg. 2019, 6, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.V.; Law, T.J.; Needham, D.M. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Ely, E.W.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Patel, M.B. The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Crit. Care Clin. 2017, 33, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweickert, W.D.; Pohlman, M.C.; Pohlman, A.S.; Nigos, C.; Pawlik, A.J.; Esbrook, C.L.; Spears, L.; Miller, M.; Franczyk, M.; Deprizio, D. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009, 373, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestroni, G.; Bertolotti, G. EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): An instrument for measuring quality of life. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2012, 78, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, R.A.; Adhikari, N.K.; Bhagwanjee, S. Clinical review: Critical care in the global context–disparities in burden of illness, access, and economics. Crit. Care 2008, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, J.S.; Alahamri, M.D.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alamoudi, A.O.; Alotaibi, N.Z.; Ghazwani, A.A.; Aldhahir, A.M.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Obaidan, A.; Alharbi, A.F. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated ICU patients in Saudi Arabia: Results of an ICU-wide national survey. Heart Lung 2022, 56, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, M.S.; Waked, I.S.; Amin, F.M.; Al-Quliti, K.W.; Manzar, M.D. Effectiveness of an early mobility protocol for stroke patients in Intensive Care Unit. Neurosci. J. 2019, 24, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, M.; Awajeh, A.; Khraisat, F. Knowledge and attitude about pain and pain management among critical care nurses in a tertiary hospital. J. Intensive Crit. Care 2017, 3, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, A.M.; Pandaan, I.N.; Alsufyani, A.M.; Almutiri, D.R.; Alhindi, A.A.; Alhusseinan, K.S. Managing patients’ pain in the intensive care units. Saudi Med. J. 2022, 43, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, B.; Scott, J.; Strachan, M.; Kilonzo, M.; Vale, L. Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia 2005, 60, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, T.A.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Caldwell, E.S.; Hudson, L.D.; Steinberg, K.P. The effect of acute respiratory distress syndrome on long-term survival. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 160, 1838–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme Jr, J.; Romney, J.S.; Hopkins, R.O.; Pope, D.; Chan, K.J.; Thomsen, G.; Crapo, R.O.; Weaver, L.K. Pulmonary function and health-related quality of life in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 167, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofhuis, J.G.; Spronk, P.E.; van Stel, H.F.; Schrijvers, G.J.; Rommes, J.H.; Bakker, J. The impact of critical illness on perceived health-related quality of life during ICU treatment, hospital stay, and after hospital discharge: A long-term follow-up study. Chest 2008, 133, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, F.J.; Hinge, D.; Dorsett, J.; Boyd, O.F. Quality of life and persisting symptoms in intensive care unit survivors: Implications for care after discharge. BMC Res. Notes 2009, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacanella, E.; Perez-Castejon, J.M.; Nicolas, J.M.; Masanés, F.; Navarro, M.; Castro, P.; López-Soto, A. Functional status and quality of life 12 months after discharge from a medical ICU in healthy elderly patients: A prospective observational study. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batawi, S.; Tarazan, N.; Al-Raddadi, R.; Al Qasim, E.; Sindi, A.; Al Johni, S.; Al-Hameed, F.M.; Arabi, Y.M.; Uyeki, T.M.; Alraddadi, B.M. Quality of life reported by survivors after hospitalization for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvande, M.E.; Angel, S.; Højager Nielsen, A. Humanizing intensive care: A scoping review (HumanIC). Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearse, R.M.; Moreno, R.P.; Bauer, P.; Pelosi, P.; Metnitz, P.; Spies, C.; Vallet, B.; Vincent, J.-L.; Hoeft, A.; Rhodes, A. Mortality after surgery in Europe: A 7 day cohort study. Lancet 2012, 380, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canet, J.; Mazo, V. Postoperative pulmonary complications. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010, 76, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Hundall Stamm, B. Professional Quality of Life Measure: Compassion, Satisfaction, and Fatigue Version 5 (ProQOL). 2009. Available online: https://socialwork.buffalo.edu/content/dam/socialwork/home/self-care-kit/compassion-satisfaction-and-fatigue-stamm-2009.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Wawrzyniak, K.M.; Finkelman, M.; Schatman, M.E.; Kulich, R.J.; Weed, V.F.; Myrta, E.; DiBenedetto, D.J. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule-2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) in a chronic pain population being considered for chronic opioid therapy. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.R.; Mathew, R.; Keding, A.; Marshall, H.C.; Brown, J.M.; Jayne, D.G. The impact of postoperative complications on long-term quality of life after curative colorectal cancer surgery. Ann. Surg. 2014, 259, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, S.J.; Francis, J.; Dilley, J.; Wilson, R.J.T.; Howell, S.J.; Allgar, V. Measuring outcomes after major abdominal surgery during hospitalization: Reliability and validity of the Postoperative Morbidity Survey. Perioper. Med. 2013, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, E.; Eyawo, O.; Lockhart, I.; Kelly, S.; Wu, P.; Ebbert, J.O. Smoking cessation reduces postoperative complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 2011, 124, 144–154.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.; Lam, D.P.; Abrishami, A.; Chan, M.T.; Chung, F. Short-term preoperative smoking cessation and postoperative complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Anesth./J. Can. D’anesthésie 2012, 59, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, D.O.; Warltier, D.C. Perioperative abstinence from cigarettes: Physiologic and clinical consequences. J. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. 2006, 104, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, V.A.; Cornell, J.E.; Smetana, G.W. Strategies to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications after noncardiothoracic surgery: Systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; DeBoard, Z.; Gauvin, J.M. Prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications. Surg. Clin. 2015, 95, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhabah, D.N.; Martino, F.; Ambrosino, N. Peri-operative physiotherapy. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2013, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsura, M.; Kuriyama, A.; Takeshima, T.; Fukuhara, S.; Furukawa, T.A. Preoperative inspiratory muscle training for postoperative pulmonary complications in adults undergoing cardiac and major abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 10, CD010356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mans, C.M.; Reeve, J.C.; Elkins, M.R. Postoperative outcomes following preoperative inspiratory muscle training in patients undergoing cardiothoracic or upper abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Ricci, N.A.; Suster, É.A.; Paisani, D.M.; Chiavegato, L.D. Effects of early mobilisation in patients after cardiac surgery: A systematic review. Physiotherapy 2017, 103, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.C.; Moonesinghe, S.R.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Kuper, M.; McMeeking, A.; Oliver, C.M.; Galsworthy, M.J.; Mythen, M.G.; National Enhanced Recovery Partnership Advisory Board. Enhanced recovery from surgery in the UK: An audit of the enhanced recovery partnership programme 2009–2012. BJA Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 115, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, M.; Rosenkranz, P.; McCabe, K.; Rosen, J.; McAneny, D. I COUGH: Reducing postoperative pulmonary complications with a multidisciplinary patient care program. JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 740–745, Erratum in J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1974, 56, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Conway, D.; Thomas, N.; Cummings, D.; Atkinson, D. Impact of a peri-operative quality improvement programme on postoperative pulmonary complications. Anaesthesia 2017, 72, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelock, P. Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology: The Magic of Our Connection: As ASHA’s “Identify the Signs” campaign educates the public about our professions, it reminds us of the links between them. ASHA Lead. 2013, 18, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHA. Learn About the CSD Professions: Audiology. Available online: https://www.asha.org/students/audiology/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Association ASLH. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). 2020. Available online: https://www.asha.org/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Cox, R.M.; Alexander, G.C. Measuring satisfaction with amplification in daily life: The SADL scale. Ear Hear. 1999, 20, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.R.; Frattali, C.; Holland, A.L.; Thompson, C.K.; Caperton, C.J.; Slater, S.C. Quality of Communication Life Scale: Manual; American Speech-Language Hearing Association: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ciorba, A.; Bianchini, C.; Pelucchi, S.; Pastore, A. The impact of hearing loss on the quality of life of elderly adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eadie, P.; Conway, L.; Hallenstein, B.; Mensah, F.; McKean, C.; Reilly, S. Quality of life in children with developmental language disorder. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2018, 53, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.J.; Shenton, R.C.; Taylor, M.J. The economics of screening infants at risk of hearing impairment: An international analysis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 76, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olusanya, B.O. Screening for neonatal deafness in resource-poor countries: Challenges and solutions. Res. Rep. Neonatol. 2015, 5, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindawas, S.M.; Vennu, V. The national and regional prevalence rates of disability, type, of disability and severity in Saudi Arabia—Analysis of 2016 demographic survey data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disability Survey. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/disability_survey_2017_en.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Zakzouk, S.M.; Fadle, K.A.; Al Anazy, F.H. Familial hereditary progressive sensorineural hearing loss among Saudi population. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 1995, 32, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delivery Plan. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/hstp/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- National Program for Hearing Impairmen. Available online: https://shc.gov.sa/Arabic/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- MOH Launches the 1st Phase of Newborn Screening for Hearing-Loss and CCHD Program. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2016-10-09-001.aspx#:~:text=The%20Ministry%20of%20Health%20(MOH,in%2030%20MOH's%20referral%20hospitals (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- 90% of the Newborn Had Cardiac Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/news-2018-03-12-003.aspx (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Jorgensen, L.E. Verification and validation of hearing aids: Opportunity not an obstacle. J. Otol. 2016, 11, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.A. Verification and validation measures of hearing aid outcome: Audiologists’ practice in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Health Sci. 2020, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, H.B.; Chisolm, T.H.; McManus, M.; McArdle, R. Initial-fit approach versus verified prescription: Comparing self-perceived hearing aid benefit. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2012, 23, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.A. Audiology and speech-language pathology practice in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi, A.A.; Al Fraih, S.S. Public Awareness of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology in Saudi Arabia. Majmaah J. Health Sci. 1970, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, M.A.; Sheeshah, H. The human right to communicate: A survey of available services in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2018, 20, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Al Awaji, N.N.; AlMudaiheem, A.A.; Mortada, E.M. Changes in speech, language and swallowing services during the COVID-19 pandemic: The perspective of speech-language pathologists in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.X.; Moir, M.; Latkin, C.A.; Hall, B.J.; Nguyen, C.T.; Ha, G.H.; Nguyen, N.B.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R. Global research mapping of substance use disorder and treatment 1971–2017: Implications for priority setting. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2019, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudet, A.B. The case for considering quality of life in addiction research and clinical practice. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2011, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alshomrani, A.T.; Khoja, A.T.; Alseraihah, S.F.; Mahmoud, M.A. Drug use patterns and demographic correlations of residents of Saudi therapeutic communities for addiction. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2017, 12, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Adult Tobacco Survey. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/data-reporting/saudi-arabia/ksa_gats_2019_factsheet_rev_4feb2021-508.pdf?sfvrsn=c349a97a_1&download=true (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- AbuMadini, M.S.; Rahim, S.I.; Al-Zahrani, M.A.; Al-Johi, A.O. Two decades of treatment seeking for substance use disorders in Saudi Arabia: Trends and patterns in a rehabilitation facility in Dammam. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 97, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Drug Report 2017. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2017/index.html (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Saquib, N.; Rajab, A.M.; Saquib, J.; AlMazrou, A. Substance use disorders in Saudi Arabia: A scoping review. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, I.M.; Fahmy, M.T.; Haggag, W.L.; Mohamed, K.A.; Baalash, A.A. Dual diagnosis and suicide probability in poly-drug users. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2016, 26, 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Chinnian, R.R.; Taylor, L.R.; Al Subaie, A.; Sugumar, A.; Al Jumaih, A.A. A controlled study of personality patterns in alcohol and heroin abusers in Saudi Arabia. J. Psychoact. Drugs 1994, 26, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, H.; Barton, P.; Brijnath, B. Self-reported depression and its associated factors among male inpatients admitted for substance use disorders in Saudi Arabia. J. Subst. Use 2015, 20, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nahedh, N. Relapse among substance-abuse patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 1999, 5, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, R.; Becker, M. The Wisconsin Quality of Life Index: A multidimensional model for measuring quality of life. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.; Powell, J.; Marshall, E.; Peters, T. Quality of life in alcohol-dependent subjects–a review. Qual. Life Res. 1999, 8, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiffany, S.T.; Friedman, L.; Greenfield, S.F.; Hasin, D.S.; Jackson, R. Beyond drug use: A systematic consideration of other outcomes in evaluations of treatments for substance use disorders. Addiction 2012, 107, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chang, K.-C.; Wang, J.-D.; Lee, L.J.-H. Quality of life and its determinants for heroin addicts receiving a methadone maintenance program: Comparison with matched referents from the general population. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2016, 115, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudet, A.B.; Becker, J.B.; White, W.L. Don’t wanna go through that madness no more: Quality of life satisfaction as predictor of sustained remission from illicit drug misuse. Subst. Use Misuse 2009, 44, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeyer, J.; Vanderplasschen, W.; Lammertyn, J.; van Nieuwenhuizen, C.; Sabbe, B.; Broekaert, E. Current quality of life and its determinants among opiate-dependent individuals five years after starting methadone treatment. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colpaert, K.; De Maeyer, J.; Broekaert, E.; Vanderplasschen, W. Impact of addiction severity and psychiatric comorbidity on the quality of life of alcohol-, drug-and dual-dependent persons in residential treatment. Eur. Addict. Res. 2013, 19, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, M.; Danovitch, I.; IsHak, W.W. Quality of life and smoking. Am. J. Addict. 2014, 23, 540–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, D.; Mattson, M.E.; Cisler, R.A.; Longabaugh, R.; Zweben, A. Quality of life as an outcome measure in alcoholism treatment research. J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. 2005, 15, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolf, H.; Watts, J. Quality of life in substance abuse and dependency. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2002, 14, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.W.; Larson, M.J. Quality of life assessments by adult substance abusers receiving publicly funded treatment in Massachusetts. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2003, 29, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makeen, A.M.; Alanazi, A.M.; AlAhmari, M.D.; Murriky, A.A.; Alfaraj, M.; Al-Zalabani, A.H. Delphi consensus on research priorities in tobacco use and substance abuse in Saudi Arabia. J. Ethn. Subst. Abus. 2020, 21, 1296–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassounah, M.M.; Al-Zalabani, A.H.; AlAhmari, M.D.; Murriky, A.A.; Makeen, A.M.; Alanazi, A.M. Implementation of cigarette plain packaging: Triadic reactions of consumers, state officials, and tobacco companies—The case of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anti-smoking Legislation and Regulations. Available online: http://nctc.gov.sa/Category/43/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B9%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%81-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%86%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%88%D8%B7%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A9 (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- The National Committee for Narcotics Control 2007. Available online: https://www.moi.gov.sa/wps/portal/Home/sectors/narcoticscontrol/contents/!ut/p/z1/pZJBU8IwEIX_Chw4MtmS0IZjYLRBUKdgKc3FSZOoUWihBFB_vcXRiyNUh9w28_blfbtBAs2RyOXOPkpni1wuqjoV_j0MCeEe6YzCbtwHFkWjWa9z4YHfRcmnYBAyToIxAB2HXRgyHk96EcbAMBJ_6Ycjh0Fd_wwJJFTuVu4JpbksVeGs2jRUkbuyWLTglyuZFVvX0LY0yhWldKYFeuus2RysVspqlGqler4BIJpkGQYtsTYPQWZ0oCTFPv2OfTyXOE01NTm6qmOrhm-f12vBKsIqvHl1aH4uYnKAPPHsMPgpAEYvgTE84zyIOrfU-xKc2nkdflqNLzia4ZqgZGfNHsV5US6rXzj9x2Z4rbt3hnuNdXCG9WoZx0uK39ph0n6Z8Pf-TTscZHR_x5rNDzB4AuE!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206081 (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Fazey, C.S. The commission on narcotic drugs and the United Nations International Drug Control Programme: Politics, policies and prospect for change. Int. J. Drug Policy 2003, 14, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anti-Smoking Clinics. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Projects/TCP/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Al-Nimr, Y.M.; Farhat, G.; Alwadey, A. Factors affecting smoking initiation and cessation among Saudi women attending smoking cessation clinics. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2020, 20, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshomrani, A.T. Saudi addiction therapeutic communities: Are they implementing the essential elements of addiction therapeutic communities? Neurosci. J. 2016, 21, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.; Maisto, S.A. Relapse to alcohol and other drug use in treated adolescents: Review and reconsideration of relapse as a change point in clinical course. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenziger, O.N.; Ford, L.; Yazidjoglou, A.; Joshy, G.; Banks, E. E-cigarette use and combustible tobacco cigarette smoking uptake among non-smokers, including relapse in former smokers: Umbrella review, systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guydish, J.; Passalacqua, E.; Pagano, A.; Martínez, C.; Le, T.; Chun, J.; Tajima, B.; Docto, L.; Garina, D.; Delucchi, K. An international systematic review of smoking prevalence in addiction treatment. Addiction 2016, 111, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, J.A.; Roebroeck, M.E.; van Schaardenburgh, N.; Floothuis, M.C.; Miedema, H.S. Improved occupational performance of young adults with a physical disability after a vocational rehabilitation intervention. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2014, 24, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Vocational Rehabilitation; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeckel, K. Costs and benefits in vocational education and training. Paris: Organ. Econ. Coop. Dev. 2008, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha, R.B.; Ali, M.M.; Bari, S.; Amat, S. Supportive and Suppressive Factors in the Improvement of Vocational Special Needs Education: A Case Study of Malaysia; ERIC Institute of Education Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Polidano, C.; Mavromaras, K. Participation in and Completion of Vocational Education and Training for People with a Disability. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2011, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Gervey, R.; Chan, F.; Chou, C.-C.; Ditchman, N. Vocational rehabilitation services and employment outcomes for people with disabilities: A United States study. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2008, 18, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.R.; Fairweather, J.S.; Leahy, M.J. Quality of life as a potential rehabilitation service outcome: The relationship between employment, quality of life, and other life areas. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2013, 57, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, M.A.; Armstrong, A.J.; Barrett, K.; Ellenbogen, P.S.; Jackson, M.N. Vocational rehabilitation services for individuals with spinal cord injury. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2006, 25, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.; Bax, M.; Smyth, D. The Health and Social Needs of Young Adults with Physical Disabilities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Country Profile on Disability: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/76489 (accessed on 2 October 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alanazi, A.M.; Almutairi, A.M.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Alotaibi, T.F.; AbuNurah, H.Y.; Olayan, L.H.; Aljuhani, T.K.; Alanazi, A.A.; Aldriwesh, M.G.; Alamri, H.S.; et al. The Intersection of Health Rehabilitation Services with Quality of Life in Saudi Arabia: Current Status and Future Needs. Healthcare 2023, 11, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030389

Alanazi AM, Almutairi AM, Aldhahi MI, Alotaibi TF, AbuNurah HY, Olayan LH, Aljuhani TK, Alanazi AA, Aldriwesh MG, Alamri HS, et al. The Intersection of Health Rehabilitation Services with Quality of Life in Saudi Arabia: Current Status and Future Needs. Healthcare. 2023; 11(3):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030389

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlanazi, Abdullah M., Abrar M. Almutairi, Monira I. Aldhahi, Tareq F. Alotaibi, Hassan Y. AbuNurah, Lafi H. Olayan, Turki K. Aljuhani, Ahmad A. Alanazi, Marwh G. Aldriwesh, Hassan S. Alamri, and et al. 2023. "The Intersection of Health Rehabilitation Services with Quality of Life in Saudi Arabia: Current Status and Future Needs" Healthcare 11, no. 3: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030389

APA StyleAlanazi, A. M., Almutairi, A. M., Aldhahi, M. I., Alotaibi, T. F., AbuNurah, H. Y., Olayan, L. H., Aljuhani, T. K., Alanazi, A. A., Aldriwesh, M. G., Alamri, H. S., Alsayari, M. A., Aldhahir, A. M., Alghamdi, S. M., Alqahtani, J. S., & Alabdali, A. A. (2023). The Intersection of Health Rehabilitation Services with Quality of Life in Saudi Arabia: Current Status and Future Needs. Healthcare, 11(3), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030389