Development and Application of a Comprehensive Measure of Access to Health Services to Examine COVID-19 Health Disparities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Access to Health Services

2.2.2. Sociodemographic Variables

Race/Ethnicity

Gender Identity

Annual Household Income

Age

Marital Status

Region of Residence

Having Children under Age 18

2.2.3. Health-Related Variables

Chronic Physical Health Condition

Mental Health Condition

Disability

Health Insurance

COVID-19 Diagnosis

2.3. Analytical Approach

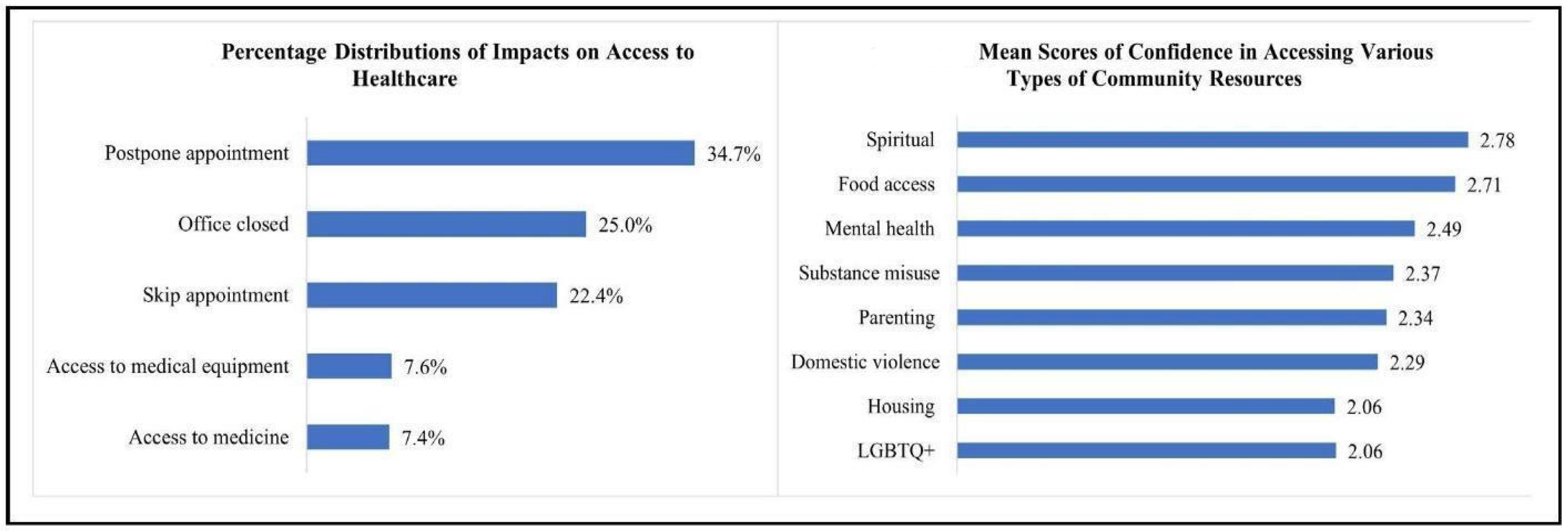

3. Results

3.1. Description of Sample

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rice, T.; Rosenau, P.; Unruh, L.Y.; Barnes, A.J.; Saltman, R.B.; van Ginneken, E. United States of America: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2013, 15, 1–431. [Google Scholar]

- Waidmann, T.A.; Rajan, S. Race and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care Access and Utilization: An Examination of State Variation. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2000, 57, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebo, K.A.; Fleishman, J.A.; Conviser, R.; Reilly, E.D.; Korthuis, P.T.; Moore, R.D.; Hellinger, J.; Keiser, P.; Rubin, H.R.; Crane, L.; et al. Racial and Gender Disparities in Receipt of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Persist in a Multistate Sample of HIV Patients in 2001. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2005, 38, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.K.; Lee, H.; Ylitalo, K.R. Child Health in the United States: Recent Trends in Racial/Ethnic Disparities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 95, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarlenski, M.; Baller, J.; Borrero, S.; Bennett, W.L. Trends in Disparities in Low-Income Children’s Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care by Family Immigration Status. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pederson, A.; Raphael, D.; Johnson, E. Gender, Race, and Health Inequalities. In Rethinking Society in the 21 Century: Critical Readings in Sociology; Canadian Scholars’ Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, J.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Chaturvedi, N.; Donovan, J. Ethnicity, Socio-Economic Position and Gender—Do They Affect Reported Health—Care Seeking Behaviour? Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavers, V.L. Measurement of Socioeconomic Status in Health Disparities Research. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2007, 99, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Read, J.G.; Gorman, B.K. Gender Inequalities in US Adult Health: The Interplay of Race and Ethnicity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1045–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, D.D.; Manheim, L.M.; Song, J.; Chang, R.W. Gender and Ethnic/Racial Disparities in Health Care Utilization Among Older Adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, S221–S233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, H.; Luk, K.M.; Chen, S.C.; Ginsberg, B.A.; Katz, K.A. Dermatologic Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Persons. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, S.C.; Kumar, S.; Freimuth, V.S.; Musa, D.; Casteneda-Angarita, N.; Kidwell, K. Racial Disparities in Exposure, Susceptibility, and Access to Health Care in the US H1N1 Influenza Pandemic. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotiner, I. The Interwoven Threads of Inequality and Health. The New Yorker. 14 April 2020. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/the-coronavirus-and-the-interwoven-threads-of-inequality-and-health (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Eberly, L.A.; Kallan, M.J.; Julien, H.M.; Haynes, N.; Khatana, S.A.M.; Nathan, A.S.; Snider, C.; Chokshi, N.P.; Eneanya, N.D.; Takvorian, S.U.; et al. Patient Characteristics Associated With Telemedicine Access for Primary and Specialty Ambulatory Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2031640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmunder, K.N.; Ruiz, J.W.; Franceschi, D.; Suarez, M.M. Demographics Associated with US Healthcare Disparities Are Exacerbated by the Telemedicine Surge during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Care Services Access to Health Care in America; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, G.; Hall, J.; Donaldson, C.; Gerard, K. Utilisation as a Measure of Equity: Weighing Heat? J. Health Econ. 1991, 10, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culyer, A.J.; van Doorslaer, E.; Wagstaff, A. Access, Utilisation and Equity: A Further Comment. J. Health Econ. 1992, 11, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.H.; Garg, A.; Bloom, G.; Walker, D.G.; Brieger, W.R.; Hafizur Rahman, M. Poverty and Access to Health Care in Developing Countries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1136, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Magadzire, B.P.; Budden, A.; Ward, K.; Jeffery, R.; Sanders, D. Frontline Health Workers as Brokers: Provider Perceptions, Experiences and Mitigating Strategies to Improve Access to Essential Medicines in South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubifard, S.; Rashidian, A.; Kebriaeezadeh, A.; Majdzadeh, R.; Hosseini, S.A.; Sari, A.A.; Salamzadeh, J. Developing a Conceptual Framework and a Tool for Measuring Access to, and Use of, Medicines at Household Level (HH-ATM Tool). Public Health 2015, 129, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiga, S.; Hinton, E. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2018. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/ (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Kurtzleben, D. Job Losses Higher Among People of Color During Coronavirus Pandemic. NPR. 2020. Available online: https://www.nprillinois.org/generationlisten/2020-04-22/minorities-often-work-these-jobs-they-were-among-first-to-go-in-coronavirus-layoffs (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Lopez, L.; Hart, L.H.; Katz, M.H. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Related to COVID-19. JAMA 2021, 325, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolific. Available online: https://www.prolific.co (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Peer, E.; Rothschild, D.; Gordon, A.; Evernden, Z.; Damer, E. Data Quality of Platforms and Panels for Online Behavioral Research. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 54, 1643–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Bavik, Y.L.; Mount, M.; Shao, B. Data Collection via Online Platforms: Challenges and Recommendations for Future Research. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 1380–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palan, S.; Schitter, C. Prolific.Ac—A Subject Pool for Online Experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 2018, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Birrell, E.; Lerner, A. Replication: How Well Do My Results Generalize Now? The External Validity of Online Privacy and Security Surveys. USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 367–385. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, A.; Sreeganga, S.D.; Ramaprasad, A. Access to Healthcare during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A.D.; Okeagu, C.N.; Pham, A.D.; Silva, R.A.; Hurley, J.J.; Arron, B.L.; Sarfraz, N.; Lee, H.N.; Ghali, G.E.; Gamble, J.W.; et al. Economic Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Facilities and Systems: International Perspectives. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 35, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.R.; Getz, C.L.; Cohen, B.E.; Cole, B.J.; Donnally, C.J. Practice Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2020, 28, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, T.; Lodhi, S.H.; Kapadia, S.; Shah, G.V. Community and Healthcare System-Related Factors Feeding the Phenomenon of Evading Medical Attention for Time-Dependent Emergencies during COVID-19 Crisis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e237817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Python StatsModels Library 2022. Available online: www.statsmodels.org (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Alexander, G.C.; Qato, D.M. Ensuring Access to Medications in the US During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 2020, 324, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayati, N.; Saiyarsarai, P.; Nikfar, S. Short and Long Term Impacts of COVID-19 on the Pharmaceutical Sector. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 28, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, J.C.; Mackey, T.K. Why the COVID-19 Pandemic Should Be a Call for Action to Advance Equitable Access to Medicines. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.L.; Lindauer, M.; Farrell, M.E. A Pandemic within a Pandemic—Intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2302–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, C.; Renedo, A.; Miles, S. Community Participation Is Crucial in a Pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1676–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Chen, C.-C.; Nie, X.; Zhu, J.; Hu, R. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Access to Primary Care Among People With Chronic Conditions. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2014, 27, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.; Witten, K.; Hiscock, R.; Blakely, T. Are Socially Disadvantaged Neighbourhoods Deprived of Health-Related Community Resources? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 36, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, W.-C. Culturally Adapting Psychotherapy for Asian Heritage Populations: An Evidence-Based Approach; Practical Resources for the Mental Health Professional; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 978-0-12-810404-0. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Galea, S. Racism and the COVID-19 Epidemic: Recommendations for Health Care Workers. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 956–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistica Internet User Penetration in the United States from 2018 to 2027. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/590800/internet-usage-reach-usa/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

| Factors | Items | Components | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Access to Visits | Could not go to an appointment because the office was closed | 0.644 | 0.221 |

| Had to postpone a healthcare appointment that you have rescheduled or intend to reschedule | 0.802 | −0.030 | |

| Had to skip a healthcare appointment | 0.670 | 0.116 | |

| Access to Medicine and Equipment | Could not obtain necessary equipment or supplies | 0.092 | 0.804 |

| Could not obtain necessary medications | 0.068 | 0.798 | |

| Rotation Sum of Squared Loadings | Total | 2.122 | 1.104 |

| % Variance | 35.36 | 18.394 | |

| Cumulative Variance | 35.362 | 53.756 | |

| Components and Items | Range of Scores | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Access to healthcare | ||

| Access to medicine and medical equipment | 0–2 | 0.65 |

| Could not obtain necessary equipment or supplies | 0–1 | |

| Could not obtain necessary medications | 0–1 | |

| Access to healthcare visits | 0–3 | 0.66 |

| Could not go to an appointment because the office was closed | 0–1 | |

| Had to postpone a healthcare appointment that you have rescheduled or intend to reschedule | 0–1 | |

| Had to skip a healthcare appointment | 0–1 | |

| Access to community resources | ||

| Confidence in accessing following community resources: | 0–32 | 0.89 |

| Food access support | 0–4 | |

| Housing support | 0–4 | |

| Domestic violence resources | 0–4 | |

| Mental health resources | 0–4 | |

| Substance misuse resources | 0–4 | |

| Parenting/family support services | 0–4 | |

| LGBTQ+ support | 0–4 | |

| Spiritual/religious resources | 0–4 |

| Impact on Access to Medicine and Medical Equipment | Impact on Access to Healthcare Visits | Confidence in Accessing Community Resources | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p a | β (SE) | p a | β (SE) | p a | |

| n = 1491 | Range = 0–2 Mean (SD) = 0.15 (0.44) R2 = 0.111 | Range 0–3 Mean (SD) = 0.82 (0.97) R2 = 0.090 | Range 0–32 Mean (SD) = 19.10 (7.21) R2 = 0.060 | |||

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian (5.8%) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.463 | 0.04 (0.11) | 0.725 | 1.66 (0.83) | 0.046 |

| Black or African American (12.2%) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.302 | 0.12 (0.08) | 0.135 | 0.56 (0.60) | 0.355 |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin (3.4%) | 0.01 (0.06) | 0.927 | 0.01 (0.14) | 0.961 | 1.14 (1.05) | 0.278 |

| Multiracial (4.8%) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.455 | 0.29 (0.12) | 0.013 | 0.57 (0.88) | 0.517 |

| White (72.4%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Other/Prefer not to say (1.3%) | 0.18 (0.10) | 0.058 | 0.13 (0.21) | 0.556 | 3.70 (1.62) | 0.023 |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| Less than USD 25,000 (16.2%) | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.144 | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.167 | 2.04 (0.79) | 0.010 |

| USD 25,000 to 34,999 (8.9%) | 0.05 (0.05) | 0.372 | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.262 | 2.75 (0.88) | 0.002 |

| USD 35,000 to 49,999 (13.9%) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.647 | 0.26 (0.10) | 0.012 | 1.78 (0.79) | 0.024 |

| USD 50,000 to 74,999 (16.6%) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.746 | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.154 | 1.48 (0.75) | 0.047 |

| USD 75,000 to 99,999 (14.0%) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.830 | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.046 | 1.20 (0.76) | 0.117 |

| USD 100,000 to 149,999 (16.8%) | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.024 | 0.17 (0.10) | 0.090 | 0.74 (0.73) | 0.314 |

| USD 150,000 or more (10.5%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Prefer not to say (3.2%) | 0.02 (0.07) | 0.790 | 0.37 (0.16) | 0.024 | 1.09 (1.23) | 0.376 |

| Gender identity | ||||||

| Cisgender female (47.1%) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.059 | 0.14 (0.05) | 0.008 | 0.45 (0.41) | 0.267 |

| Cisgender male (44.4%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Other gender identity (1.9%) | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.228 | 0.13 (0.18) | 0.496 | 2.75 (1.39) | 0.048 |

| Prefer not to say (6.6%) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.440 | 0.11 (0.11) | 0.295 | 0.19 (0.79) | 0.811 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Divorced (9.9%) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.347 | 0.02 (0.09) | 0.840 | 0.21 (0.70) | 0.766 |

| Married (45.4%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Not married, but in a relationship and living together (7.6%) | 0.10 (0.05) | 0.038 | 0.13 (0.10) | 0.197 | 0.26 (0.78) | 0.736 |

| Not married, but in a relationship and not living together (5.6%) | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.070 | 0.10 (0.13) | 0.449 | 0.03 (0.95) | 0.978 |

| Separated (0.8%) | 0.22 (0.12) | 0.078 | 0.07 (0.28) | 0.790 | 1.63 (2.08) | 0.433 |

| Single/never married (27.6%) | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.055 | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.186 | 0.01 (0.58) | 0.987 |

| Widowed (2.1%) | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.872 | 0.22 (0.17) | 0.206 | 2.62 (1.31) | 0.046 |

| Unknown or prefer not to say (0.9%) | 0.00 (0.12) | 0.983 | 0.28 (0.26) | 0.275 | 4.92 (1.94) | 0.012 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18 to 25 (18.2%) | 0.01 (0.04) | 0.713 | 0.06 (0.09) | 0.492 | 0.68 (0.65) | 0.298 |

| 26 to 40 (26.8%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| 41 to 64 (43.0) | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.037 | 0.02 (0.07) | 0.825 | 0.54 (0.50) | 0.277 |

| 65 or older (11.9%) | 0.17 (0.04) | <0.001 | 0.24 (0.10) | 0.015 | 1.58 (0.74) | 0.032 |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Midwest (18.0%) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.509 | 0.23 (0.09) | 0.008 | 0.30 (0.66) | 0.647 |

| Northeast (14.4%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| South (37.0%) | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.136 | 0.22 (0.08) | 0.004 | 0.22 (0.58) | 0.710 |

| West (20.7%) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.067 | 0.15 (0.08) | 0.072 | 0.19 (0.64) | 0.769 |

| Prefer not to say (9.9%) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.552 | 0.16 (0.10) | 0.122 | 0.19 (0.78) | 0.803 |

| Any children under age 18 | ||||||

| Yes (29.0%) | 0.17 (0.03) | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.06) | 0.002 | 0.77 (0.49) | 0.112 |

| No (71.0%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Pre-existing health conditions | ||||||

| Any chronic physical health condition | ||||||

| Yes (45.9%) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.001 | 0.22 (0.05) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.41) | 0.348 |

| No (54.1%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Any mental health condition | ||||||

| Yes (34.9%) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.593 | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.002 | 0.32 (0.42) | 0.434 |

| No (65.1%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Any disability | ||||||

| Yes (20.2%) | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.007 | 0.15 (0.06) | 0.021 | 0.09 (0.48) | 0.858 |

| No (79.8%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| Any health insurance | ||||||

| Yes (91.0%) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.547 | 0.29 (0.09) | 0.001 | 1.39 (0.68) | 0.040 |

| No (9.0%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

| COVID-19 diagnosis in self or family | ||||||

| Yes (30.8%) | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.003 | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.026 | 0.11 (0.41) | 0.797 |

| No (69.2%) | ref | -- | ref | -- | ref | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wakeel, F.; Jia, H.; He, L.; Shehadeh, K.S.; Napper, L.E. Development and Application of a Comprehensive Measure of Access to Health Services to Examine COVID-19 Health Disparities. Healthcare 2023, 11, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030354

Wakeel F, Jia H, He L, Shehadeh KS, Napper LE. Development and Application of a Comprehensive Measure of Access to Health Services to Examine COVID-19 Health Disparities. Healthcare. 2023; 11(3):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030354

Chicago/Turabian StyleWakeel, Fathima, Haiyan Jia, Lifang He, Karmel S. Shehadeh, and Lucy E. Napper. 2023. "Development and Application of a Comprehensive Measure of Access to Health Services to Examine COVID-19 Health Disparities" Healthcare 11, no. 3: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030354

APA StyleWakeel, F., Jia, H., He, L., Shehadeh, K. S., & Napper, L. E. (2023). Development and Application of a Comprehensive Measure of Access to Health Services to Examine COVID-19 Health Disparities. Healthcare, 11(3), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030354