Family Functioning, Illness-Related Self-Regulation Processes, and Clinical Outcomes in Major Depression: A Prospective Study in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Major Depressive Disorder

1.2. Family Functioning in MDD

1.3. Self-Regulation Processes in MDD

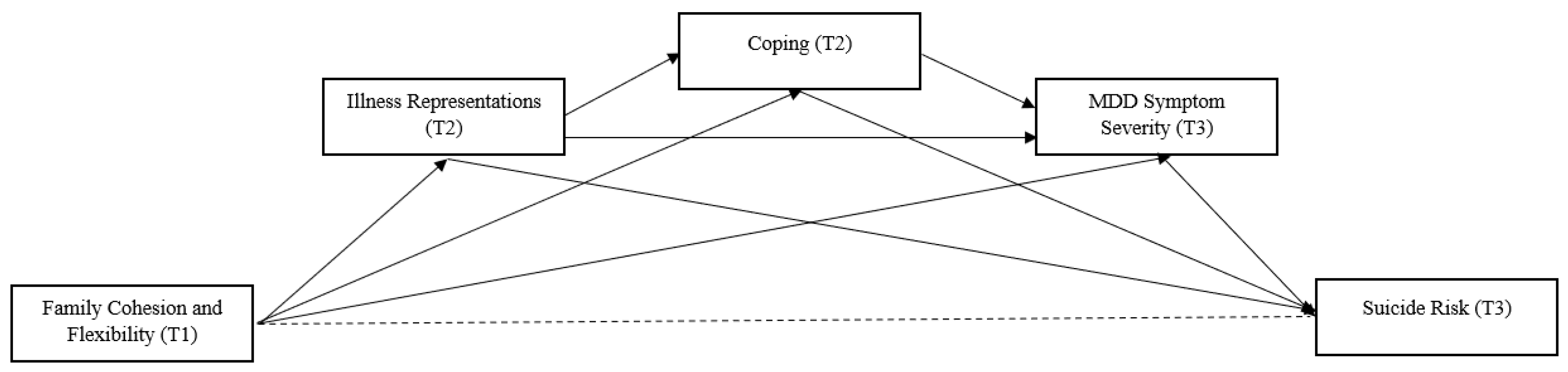

1.4. Purpose of the Present Study

2. Methods

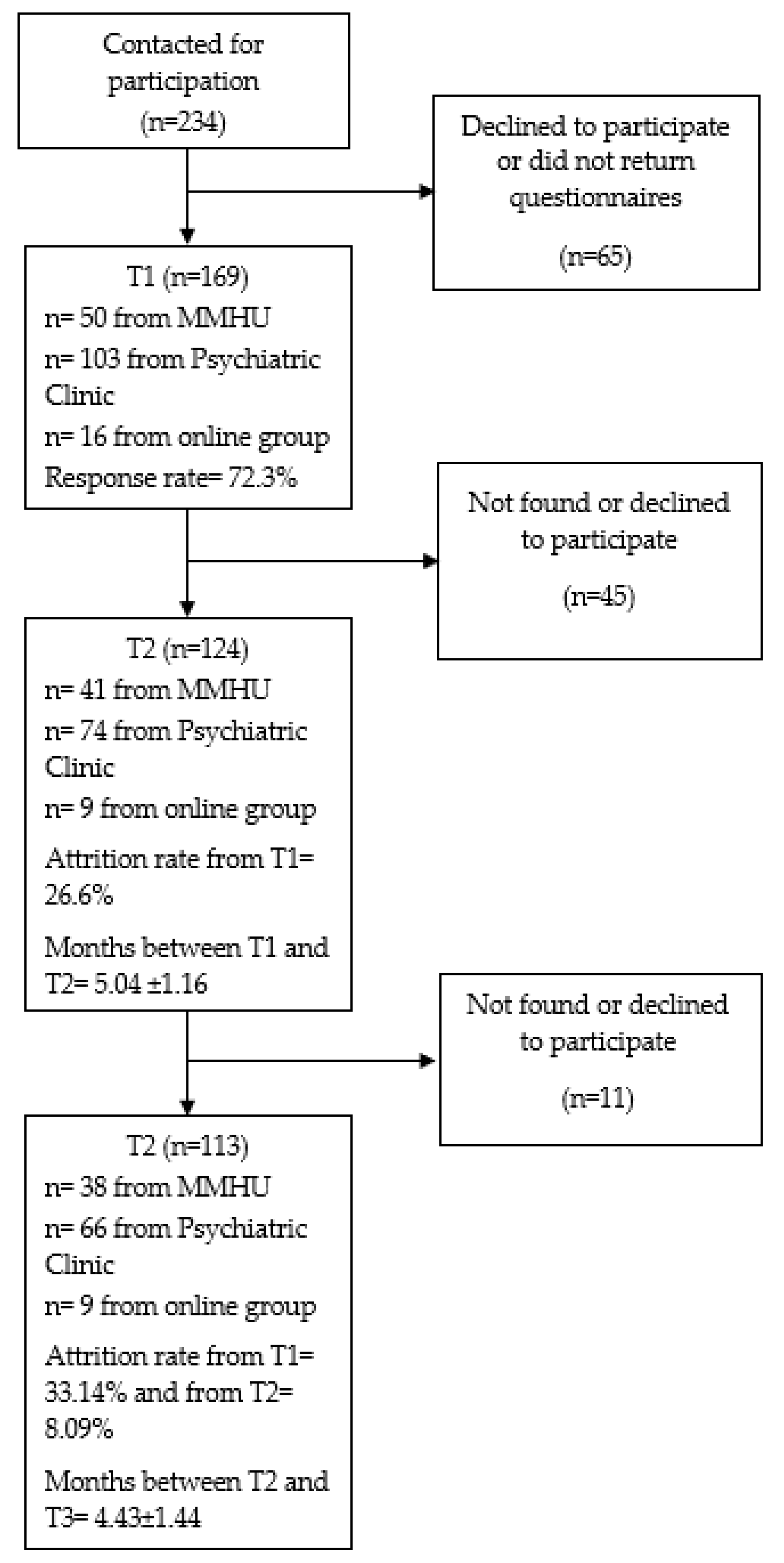

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.2.2. Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales IV Package

2.2.3. Illness Perception Questionnaire-Mental Health

2.2.4. Brief Cope Orientation to Problems Experienced

2.2.5. Beck Depression Inventory

2.2.6. Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics and Missing Data

3.2. Descriptives and Bivariate Correlation between the Study Variables

3.3. Confounding Variables

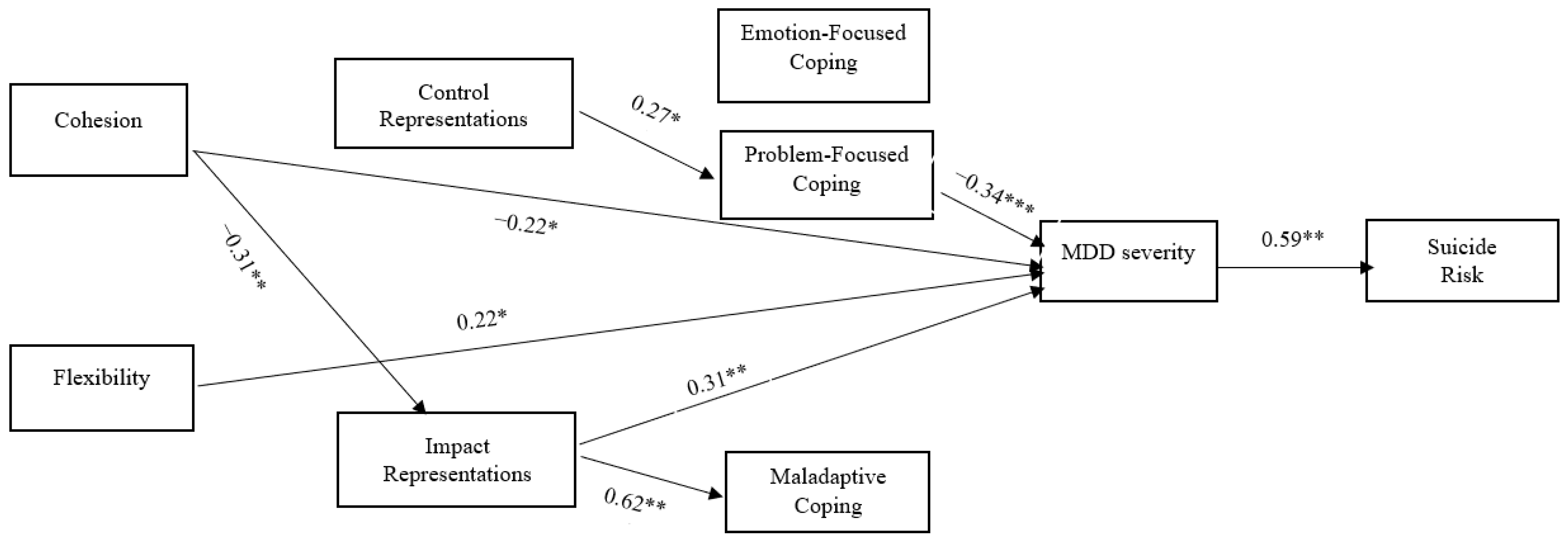

3.4. Path Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpreting Research Findings under the Light of Literature

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications for Further Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spijker, J.; Graaf, R.; Bijl, R.V.; Beekman, A.T.; Ormel, J.; Nolen, W.A. Functional disability and depression in the general population. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Acta Psychiatry Scand. 2004, 110, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustün, T.B.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Chatterji, S.; Mathers, C.; Murray, C.J. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 184, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Ferrari, A.J.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Patten, S.B.; Freedman, G.; Murray, C.J.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burcusa, S.L.; Iacono, W.G. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 959–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Jin, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheung, T.; Balbuena, L.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and planning in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of observation studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zeng, L.N.; Lu, L.; Li, X.H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Chow, I.H.I.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of suicide attempt in individuals with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of observational surveys. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1691–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordentoft, M.; Mortensen, P.B.; Pedersen, C.B. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, N.; Ran, M.S.; Liang, S.G.; SiTu, M.J.; Huang, Y.; Mansfield, A.K.; Keitner, G. Comparison of family functioning in families of depressed patients and nonclinical control families in China using the Family Assessment Device and the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales II. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, M.S.; McDermut, W.H.; Solomon, D.A.; Ryan, C.E.; Keitner, G.I.; Miller, I.W. Family functioning and mental illness: A comparison of psychiatric and nonclinical families. Fam. Process. 1997, 36, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mansfield, A.K.; Zhao, X.; Keitner, G. Family functioning in depressed and non-clinical control families. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2013, 59, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heru, A.M.; Ryan, C.E. Burden, reward and family functioning of caregivers for relatives with mood disorders: 1-year follow-up. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 83, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstock, L.M.; Keitner, G.I.; Ryan, C.E.; Solomon, D.A.; Miller, I.W. Family functioning and mood disorders: A comparison between patients with major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Chen, H.; Liang, T. Family functioning and 1-year prognosis of first-episode major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D.H.; Sprenkle, D.H.; Russell, C. Circumplex Model of marital and family systems: I. Cohesion and adaptability dimensions, family types, and clinical applications. Fam. Process. 1979, 18, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.H. Circumplex Model of family systems. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.H.; Gorall, D.M. FACES IV and the Circumplex Model. 2006. Available online: www.facesiv.com/pdf/3.innovations.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2008).

- Craddock, A.E. Family system and family functioning: Circumplex Model and FACES IV. J. Fam. Stud. 2001, 7, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breland, J.Y.; Wong, J.J.; McAndrew, L.M. Are Common Sense Model constructs and self-efficacy simultaneously correlated with self-management behaviors and health outcomes: A systematic review. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 2055102919898846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Orbell, S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol. Health 2003, 18, 141–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, H.; Brissette, I.; Leventhal, E.A. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. In The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour; Cameron, L., Leventhal, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003; pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, H.; Meyer, D.; Nerenz, D. The common sense model of illness danger. In Contributions to Medical Psychology; Rachman, S., Ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1980; pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, T.; Wittkowski, A. A systematic review of the literature exploring illness perceptions in mental health utilising the self-regulation model. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2013, 20, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanheusden, K.; van der Ende, J.; Mulder, C.L.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Verhulst, F.C.; Mackenbach, J.P. Beliefs about mental health problems and help-seeking behavior in Dutch young adults. Soc. Psych. Psych. Epid. 2009, 44, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Rass, F.; Werner, P.; Shinan-Altman, S. Cognitive illness representations among Israeli Arabs diagnosed with depression and their relationship with health-related quality of life. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glattacker, M.; Heyduck, K.; Meffert, C.; Jakob, T. Illness beliefs, treatment beliefs and information needs as starting points for patient information: The evaluation of an intervention for patients with depression. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2018, 25, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tang, C.; Liow, C.S.; Ng, W.W.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. A regressional analysis of maladaptive rumination, illness perception and negative emotional outcomes in Asian patients suffering from depressive disorder. Asian J. Psychiatry 2014, 12, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.; Moore, M.; Moss-Morris, R.; Kendrick, T. Do patients’ illness beliefs predict depression measures at six months in primary care; a longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 174, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magaard, J.L.; Löwe, B.; Brütt, A.L.; Kohlmann, S. Illness beliefs about depression among patients seeking depression care and patients seeking cardiac care: An exploratory analysis using a mixed method design. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavroeides, G.; Koutra, K. Illness representations in depression and their association with clinical and treatment outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glattacker, M.; Heyduck, K.; Meffert, C. Illness beliefs and treatment beliefs as predictors of short and middle term outcome in depression. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Battista, D.R.; Sereika, S.M.; Bruehlman, R.D.; DunbarJacob, J.; Thase, M.E. Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: Relationship to coping behavior and functional disability. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2007, 29, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.; Villaggi, B.; Beaulieu, M.D.; Lespérance, F.; Rondeau, G.; Lambert, J. Treatment preferences in patients with first episode depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 147, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Moore, M.; Moss-Morris, R.; Kendrick, T. Are patient beliefs important in determining adherence to treatment and outcome for depression? Development of the beliefs about depression questionnaire. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 133, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, E.; Onwumere, J.; Bebbington, P. Cognitive model of caregiving in psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 196, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, R.; Loios, S.; Pedro, M. Family functioning and adolescent psychological maladjustment: The mediating role of coping strategies. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, H.; Lin, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, X.; Chen, L. Relationship between family functioning and medication adherence in Chinese patients with mechanical heart valve replacement: A moderated mediation model. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 817406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohany, N.; Zainah Ahm, Z.; Rozainee, K.; Shahrazad, W.S.W. Family Functioning, self-esteem, self-concept and cognitive distortion among juvenile delinquents. Soc. Sci. 2011, 6, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 2016, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.H.; Gorall, D.M.; Tiesel, J.W. FACES IV Manual; Life Innovations: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koutra, K.; Triliva, S.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Lionis, C.; Vgontzas, A.N. Cross cultural adaptation and validation of the Greek version of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales IV Package (FACES IV Package). J. Fam. Issues 2013, 34, 1647–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteman, C.; Bolks, L.; Hutschemaekers, G. Development of the Illness Perception Questionnaire Mental Health. J. Ment. Health 2011, 20, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, T.C.; Carey, M.E.; Cradock, S.; Dallosso, H.M.; Daly, H.; Davies, M.J.; Doherty, Y.; Heller, S.; Khunti, K.; Oliver, L.; et al. Comparison of illness representations dimensions and illness representation clusters in predicting outcomes in the first year following diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: Results from the DESMOND trial. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroeides, G.; Basta, M.; Vgontzas, A.; Karademas, E.; Simos, P.; Koutra, K. Early maladaptive schema domains and suicide risk in major depressive disorder: The mediating role of patients’ illness-related self-regulation processes and symptom severity. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroeides, G.; Koutra, K. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Greek version of the illness perception questionnaire-mental health in individuals with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: Consider the brief cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Katona, C.; Livingston, G. Validity and reliability of the brief COPE in carers of people with dementia: The LASER-AD Study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2008, 196, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaitzaki, A. Posttraumatic symptoms, posttraumatic growth, and internal resources among the general population in Greece: A nation-wide survey amid the first COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapsou, M.; Panayiotou, G.; Kokkinos, C.M.; Demetriou, A.G. Dimensionality of coping: An empirical contribution to the construct validation of the brief-COPE with a Greek-speaking sample. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mpck, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemos, J. The Standardization of the Beck Depression Inventory in a Greek Population Sample. Ph.D. Thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Pantoula, E.; Siamouli, M.; Moutou, K.; Gonda, X.; Rihmer, Z.; Iacovides, A.; Akiskal, H. Development of the Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale (RASS): A population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Menard, S. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis: Sage University Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for ft indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Heppner, P.P.; Lee, D.G. Maladaptive coping and self-esteem as mediators between perfectionism and psychological distress. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2010, 48, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Dunn, T.L.; Ikizler, A.S. Multiple minority stressors and psychological distress among sexual minority women: The roles of rumination and maladaptive coping. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2014, 1, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.J.; Mata, J.; Jaeggi, S.M.; Buschkuehl, M.; Jonides, J.; Gotlib, I.H. Maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, and depressive symptoms: Variations across age and depressive state. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.S.H.; Chua, J.; Tay, G.W.N. The diagnostic and predictive potential of personality traits and coping styles in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Principles of self-regulation: Action and emotion. In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior; Higgins, E.T., Sorrentino, R.M., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- Karoly, P. Mechanisms of self-regulation: A systems view. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Palenchar, D.R.; Kelleher, K.J.; Bruehlman, R.D.; Sereika, S.; Thase, M.E. Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: A preliminary investigation. Fam. Pract. 2001, 18, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidou, A.; Anastasaki, M.; Zografaki, A.; Krasanaki, C.K.; Daskalaki, M.; Chatziorfanos, V.; Giakovidou, A.; Basta, M.; Vgontzas, A.N. Mobile mental health units in Heraklion Crete 2013–2022: Progress, difficulties and future challenges. Psychiatry 2023, 5, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.J.; Broadbent, E.; Kydd, R. Illness perceptions in mental health: Issues and potential applications. J. Ment. Health 2008, 17, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Oliván, I.; Porras-Segovia, A.; Barrigón, M.; Jiménez-Muñoz, L.; Baca-García, E. Theoretical models of suicidal behaviour: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2021, 35, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Clinical Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | MDD onset | ||||

| Male | 19 | 16.8 | <6 months | 2 | 1.8 |

| Female | 94 | 83.2 | 6–12 months | 3 | 2.7 |

| Nationality | 1–2 years | 20 | 17.7 | ||

| Greek | 111 | 98.2 | 3–4 years | 15 | 13.3 |

| Other | 2 | 1.8 | ≥5 years | 73 | 64.6 |

| Origin | Hospitalization | ||||

| Urban | 64 | 56.6 | None | 86 | 76.1 |

| Rural | 49 | 43.4 | 1 | 18 | 15.9 |

| Residence | 2 or more | 9 | 8.0 | ||

| Urban | 67 | 59.3 | Duration of hospitalization | ||

| Rural | 46 | 40.7 | Up to 10 days | 4 | 3.5 |

| Marital status | 11–20 days | 11 | 9.7 | ||

| Unmarried | 18 | 15.9 | 21–30 days | 9 | 8.0 |

| Married | 74 | 65.5 | 31+ days | 2 | 1.8 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 21 | 18.6 | No hospitalization | 87 | 77.0 |

| Education | Last hospitalization | ||||

| Elementary/High school | 37 | 32.7 | Within the last 6 months | 8 | 7.1 |

| Lyceum/Some years in university | 50 | 44.2 | 6–12 months | 4 | 3.5 |

| University degree | 26 | 23.0 | 1–2 years | 8 | 7.1 |

| Employment status | 3+ years | 6 | 5.3 | ||

| Working | 49 | 43.4 | No hospitalization | 87 | 77.0 |

| Not working | 64 | 56.6 | Suicide attempt | ||

| Monthly income | Yes | 31 | 27.4 | ||

| No individual income | 32 | 28.3 | No | 82 | 72.6 |

| 1–650 € | 42 | 37.2 | Pharmacotherapy | ||

| 651–1000 € | 30 | 26.5 | Yes | 86 | 76.1 |

| >1000 € | 9 | 8.0 | No | 27 | 23.9 |

| Living | Psychotherapy | ||||

| Alone | 10 | 8.8 | Yes | 43 | 38.1 |

| With family/partner/others | 103 | 91.2 | No | 70 | 61.9 |

| Min-Max | Mean (SD) | Min-Max | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 18–73 | 47.11 (13.96) | Age at illness’s onset | 13–67 | 40.53 (13.65) |

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s Alpha | COH | FLEX | IR | CR | EC | PFC | MC | SS | SR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COH (T1) | 1.46 | 0.49 | 0.02 | −0.39 | - a | 1 | ||||||||

| FLEX (T1) | 1.21 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.31 | - b | 0.76 *** | 1 | |||||||

| IR (T2) | 94.65 | 26.59 | −0.41 | −0.32 | 0.95 | −0.36 *** | −0.31 ** | 1 | ||||||

| CR(T2) | 46.44 | 8.16 | −0.00 | −0.41 | 0.86 | 0.14 | 0.17 | −0.67 *** | 1 | |||||

| EFC (T2) | 26.42 | 5.22 | 0.14 | −0.68 | 0.63 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.21 * | 0.24 ** | 1 | ||||

| PFC (T2) | 16.49 | 4.30 | −0.08 | −1.04 | 0.77 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.35 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.53 *** | 1 | |||

| MC (T2) | 26.11 | 5.68 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.67 | −0.25 ** | −0.22 * | 0.56 *** | −0.31 ** | −0.02 | −0.01 | 1 | ||

| SS (T3) | 17.12 | 12.23 | 0.59 | −0.73 | 0.92 | −0.24 * | −0.10 | 0.53 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.25 ** | −0.50 *** | 0.29 ** | 1 | |

| SR (T3) | 323.81 | 287.33 | 1.14 | 0.53 | 0.85 | −0.36 *** | −0.30 ** | 0.57 *** | −0.39 *** | −0.27 ** | −0.27 ** | 0.41 *** | 0.67 *** | 1 |

| Direct Effect a | Indirect Effect a | Total Effect a | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | 95% CI | p | β | SE | 95% CI | p | β | SE | 95% CI | p | |

| COH-T1 → IR-T2 | −0.31 | 0.14 | −0.56, −0.006 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - | −0.31 | 0.14 | −0.56, −0.006 | 0.04 |

| COH-T1 → CR-T2 | 0.03 | 0.15 | −0.26, 0.34 | 0.77 | - | - | - | - | 0.03 | 0.15 | −0.26, 0.34 | 0.77 |

| COH-T1 → PFC-T2 | 0.000 | 0.11 | −0.23, 0.23 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.07, 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.21, 0.36 | 0.57 |

| COH-T1 → MC-T2 | −0.005 | 0.14 | −0.26, 0.27 | 0.99 | −0.19 | 0.08 | −0.36, −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.19 | 0.12 | −0.43, 0.05 | 0.11 |

| COH-T1 → EFC-T2 | 0.08 | 0.15 | −0.20, 0.38 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.09, 0.16 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 0.14 | −0.17, 0.40 | 0.41 |

| COH-T1 → SS-T3 | −0.22 | 0.11 | −0.44, −0.005 | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.10 | −0.34, 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.36 | 0.13 | −0.61, −0.09 | 0.01 |

| COH-T1 → SR-T3 | - | - | - | - | −0.28 | 0.010 | −0.47, −0.08 | 0.01 | −0.28 | 0.10 | −0.47, −0.08 | 0.01 |

| FLEX-T1 → IR-T2 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.33, 0.18 | 0.58 | - | - | - | - | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.33, 0.18 | 0.57 |

| FLEX-T1 → CR-T2 | 0.16 | 0.14 | −0.11, 0.43 | 0.26 | - | - | - | - | 0.16 | 0.14 | −0.11, 0.43 | 0.26 |

| FLEX-T1 → PFC-T2 | −0.12 | 0.12 | −0.36, 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.07, 0.20 | 0.36 | −0.06 | 0.14 | −0.34, 0.22 | 0.64 |

| FLEX-T1 → MC-T2 | −0.04 | 0.13 | −0.30, 0.21 | 0.72 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.18, 0.12 | 0.71 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.32, 0.17 | 0.56 |

| FLEX-T1 → EFC-T2 | −0.11 | 0.12 | −0.36, 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03, 0.14 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.34, 0.19 | 0.57 |

| FLEX-T1 → SS-T3 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.01, 0.46 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.20, 0.16 | 0.87 | 0.21 | 0.14 | −0.06, 0.48 | 0.12 |

| FLEX-T1 → SR-T3 | - | - | - | - | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.09, 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.09, 0.28 | 0.28 |

| IR-T2 → PFC-T2 | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.49, 0.06 | 0.11 | - | - | - | - | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.49, 0.06 | 0.11 |

| IR-T2 → MC-T2 | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.39, 0.83 | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.39, 0.83 | 0.000 |

| IR-T2 → EFC-T2 | −0.05 | 0.15 | −0.31, 0.28 | 0.76 | - | - | - | - | −0.05 | 0.15 | −0.31, 0.28 | 0.76 |

| IR-T2 → SS-T3 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.06, 0.55 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.08 | −0.02, 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.12 | 0.18, 0.66 | 0.001 |

| IR-T2 → SR-T3 | 0.17 | 0.09 | −0.01, 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.10, 0.47 | 0.002 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.25, 0.64 | 0.000 |

| CR-T2 → PFC-T2 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.04, 0.52 | 0.02 | - | - | - | - | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.04, 0.52 | 0.02 |

| CR-T2 → MC-T2 | 0.11 | 0.12 | −0.14, 035 | 0.34 | - | - | - | - | 0.11 | 0.12 | −0.14, 0.35 | 0.34 |

| CR-T2 → EFC-T2 | 0.22 | 0.12 | −0.02, 0.47 | 0.08 | - | - | - | - | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.02, 0.47 | 0.08 |

| CR-T2 → SS-T3 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.28, 0.14 | 0.57 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.21, 0.002 | 0.05 | −0.14 | 0.11 | −0.37, 0.07 | 0.22 |

| CR-T2 → SR-T3 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.19, 0.13 | 0.68 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.23, 0.06 | 0.31 | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.30, 0.07 | 0.23 |

| PFC-T2 → SS-T3 | −0.34 | 0.09 | −0.53, −0.16 | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | −0.34 | 0.09 | −0.53, −0.16 | 0.000 |

| PFC-T2 → SR-T3 | 0.10 | 0.07 | −0.03, 0.25 | 0.14 | −0.20 | 0.06 | −0.33, −0.09 | 0.000 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.27, 0.08 | 0.29 |

| MC-T2 → SS-T3 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.11, 0.22 | 0.45 | - | - | - | - | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.11, 0.22 | 0.45 |

| MC-T2 → SR-T3 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.08, 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.06, 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.07, 0.25 | 0.27 |

| EFC-T2 → SS-T3 | 0.003 | 0.08 | −0.14, 0.16 | 0.91 | - | - | - | - | 0.003 | 0.08 | −0.14, 0.16 | 0.91 |

| EFC-T2 → SR-T3 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.26, 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.04 | −0.08, 0.10 | 0.91 | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.29, 0.05 | 0.17 |

| SS-T3 → SR-T3 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.45, 0.70 | 0.000 | - | - | - | - | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.45, 0.70 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koutra, K.; Mavroeides, G.; Basta, M.; Vgontzas, A.N. Family Functioning, Illness-Related Self-Regulation Processes, and Clinical Outcomes in Major Depression: A Prospective Study in Greece. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222938

Koutra K, Mavroeides G, Basta M, Vgontzas AN. Family Functioning, Illness-Related Self-Regulation Processes, and Clinical Outcomes in Major Depression: A Prospective Study in Greece. Healthcare. 2023; 11(22):2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222938

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoutra, Katerina, Georgios Mavroeides, Maria Basta, and Alexandros N. Vgontzas. 2023. "Family Functioning, Illness-Related Self-Regulation Processes, and Clinical Outcomes in Major Depression: A Prospective Study in Greece" Healthcare 11, no. 22: 2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222938

APA StyleKoutra, K., Mavroeides, G., Basta, M., & Vgontzas, A. N. (2023). Family Functioning, Illness-Related Self-Regulation Processes, and Clinical Outcomes in Major Depression: A Prospective Study in Greece. Healthcare, 11(22), 2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222938