Effects of Post Traumatic Growth on Successful Aging in Breast Cancer Survivors in South Korea: The Mediating Effect of Resilience and Intolerance of Uncertainty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Post-Traumatic Growth

2.3.2. Successful Aging

2.3.3. Intolerance of Uncertainty

2.3.4. Resilience

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ General and Disease-Related Characteristics

3.2. Correlations of Post-Traumatic Growth, Successful Aging, Resilience, and Intolerance of Uncertainty in Participants

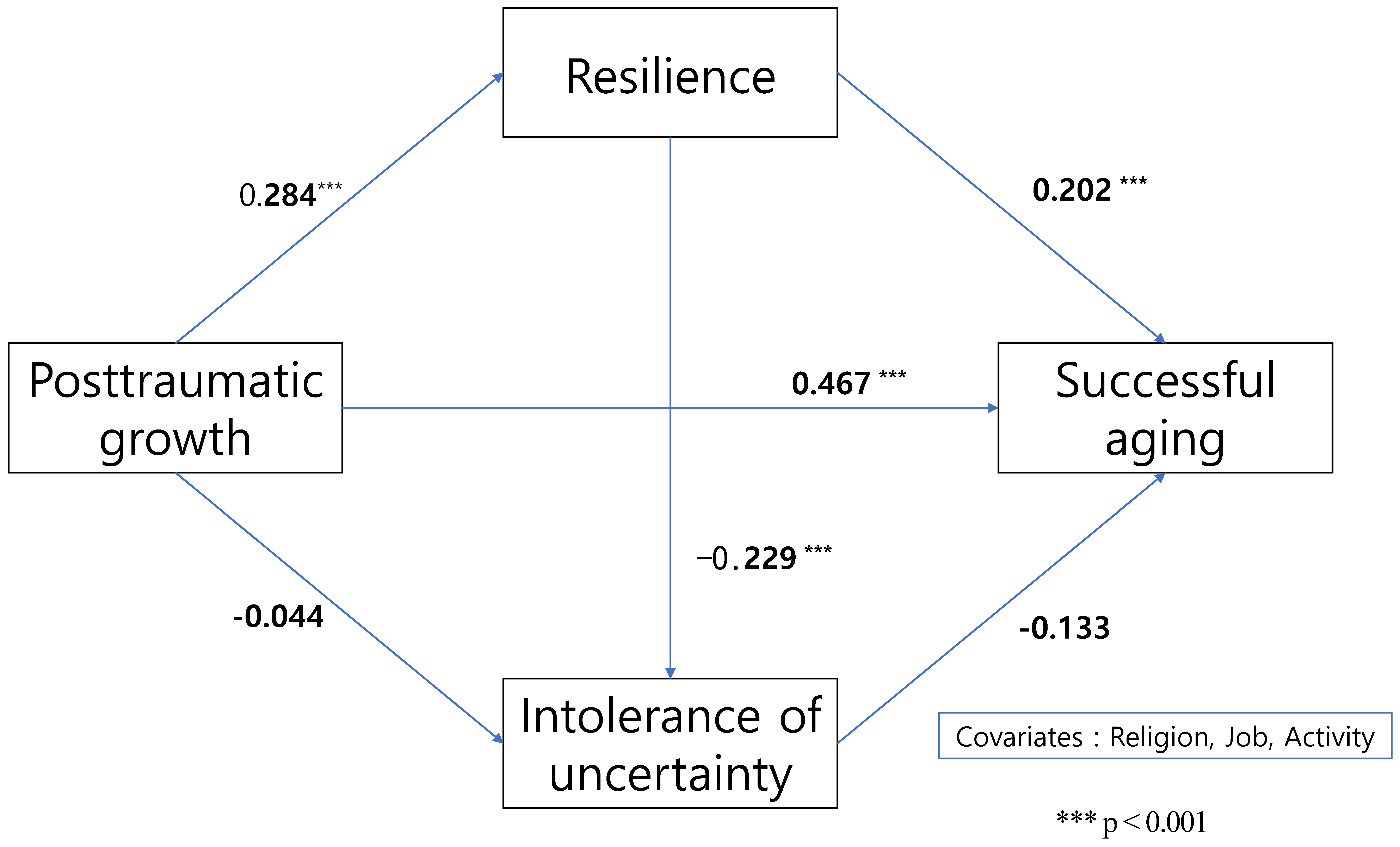

3.3. Mediating Effects of Resilience and Intolerance of Uncertainty on the Relationship between Post-Traumatic Growth and Successful Aging

4. Discussion

Limitations and future research Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Cancer Information Center. Main Contents [Internet]. Cancer in Statistics: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. Available online: https://www.cancer.go.kr/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Korean Breast Cancer Society. Main Contents [Internet]. Breast Cancer: Seoul [White Paper]. 2022. Available online: https://www.kbcs.or.kr/journal/file/221018.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Jun, S.M. Successful Aging and Related Factors in Gastric Cancer Patients after Gastrectomy. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013; pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, M. A mid-range nursing theory of successful aging. J. Theory Constr. Test. 2005, 9, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kozar-Westman, M.; Troutman-Jordan, M.; Nies, M.A. Successful aging among assisted living community older adult. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2013, 45, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrowatka, A.; Motulsky, A.; Kurteva, S.; Hanley, J.A.; Dixon, W.G.; Meguerditchian, A.N.; Tamblyn, R. Predictors of distress in female breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 165, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, Y.H. Factors Influencing Successful Aging in Breast Cancer Survivors. Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020; pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnavi, S.; Connor, K.; Davidson, J.R. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: Psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 152, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Linley, P.A.; Andrews, L.; Harris, G.; Howle, B.; Woodward, C.; Shevlin, M. Assessing positive and negative changes in the aftermath of adversity: Psychometric evaluation of the changes in outlook questionnaire. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 17, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, C.M.; An, S.H. Relationship among subjective health, psychological well-being and successful aging of elderly participating in physical activity. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2014, 53, 357–369. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.E.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, M.L.; Su, Y.L.; Wang, P.L. Posttraumatic growth and psychological distress in Chinese early-stage breast cancer survivors: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Jung, Y.S.; Jung, Y.M. Factors influencing posttraumatic growth in survivors of breast cancer. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2016, 46, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaczkowski, G.; Hayman, T.; Strelan, P.; Miller, J.; Knott, V. Complementary medicine and recovery from cancer: The importance of post-traumatic growth. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 2013, 22, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Woo, Y.J. The effect of self-compassion, self-resilience and intolerance od uncertainty on job-seeking stress: For job seekers in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Learn.-Cent. Curric. Instr. 2021, 21, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, U.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kang, J.S. Effect of uncertainty and resilience on stress for cancer patients. Stress 2018, 26, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, C.E.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Taylor, S.F. Adapting to life’s slings and arrows: Individual differences in resilience when recovering from an anticipated threat. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Jun, S.S. Factors related to posttraumatic growth in patients with colorectal cancer. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2016, 28, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.A.; Morris, B.A.; Chambers, S. A structural equation model of posttraumatic growth after prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygren, B.; Aléx, L.; Jonsén, E.; Gustafson, Y.; Norberg, A.; Lundman, B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment. Health 2005, 9, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeste, D.V.; Savla, G.N.; Thompson, W.K.; Vahia, I.V.; Glorioso, D.K.; Martin, A.S.; Palmer, B.W.; Rock, D.; Golshan, S.; Kraemer, H.C.; et al. Association between older age and more successful aging: Critical role of resilience and depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Son, Y. The effects of intolerance of uncertainty on burnout among counselor: The mediating effect of self-compassion and burnout. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 10, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S. Effect of resilience on intolerance of uncertainty in nursing university students. Nurs Forum 2019, 54, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeston, M.H.; Rhéaume, J.; Letarte, H.; Dugas, M.J.; Ladouceur, R. Why do people worry? Pers. Individ. Dif. 1994, 17, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, K.; Dugas, M.J. The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, K.A.; Dugas, M.J. Defining distinct negative beliefs about uncertainty: Validating the factor structure of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, K.; Garon, E.B.; Stanton, A.L.; Meyerowitz, B.E. Uncertainty and psychological adjustment in patients with lung cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 1396–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.M.; Hamm, A. Intolerance of uncertainty, social support, and loneliness in relation to anxiety and depressive symptoms among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2019, 28, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, S.; Matheson, K.; Cronin, T.; Anisman, H. Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: The case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.L.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Gullickson, K. Understanding health anxiety following breast cancer diagnosis. Psychol. Health Med. 2014, 19, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, Stress and Coping; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Y.J.; Song, E.K. Impact of health literacy on disease-related knowledge and adherence to self-care in patients with hypertension. J. Korean Acad. Fundam. Nurs. 2012, 19, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Yeon, K.; Han, S.T. A review on the use of effect size in nursing research. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2015, 45, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.H.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, H.S.; Park, J.H. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Korean J. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troutman, M.; Nies, M.A.; Small, S.; Bates, A. The development and testing of an instrument to measure successful aging. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2011, 4, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S. A Structural Equation Model for Successful Aging. Master’s Thesis, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea, 2016; pp. 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.K. The dysfunctional effects of chronic worry and controllable-uncontrollable threats on problem-solving. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 22, 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.M. Perceptions of successful aging and the influencing factors in middle-aged women. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2018, 19, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, S.; Musich, S.; Hawkins, K.; Alsgaard, K.; Wicker, E.R. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2016, 37, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, A.; Jenewein, J. Resilience in cancer patients. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musich, S.; Wang, S.S.; Schaeffer, J.A.; Kraemer, S.; Wicker, E.; Yeh, C.S. The association of increasing resilience with positive health outcomes among older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 44, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.M.; Lim, J.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Park, S.M. Resilience of patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasson, M.; Taubman-Ben-Ari, O.; Abu-Sharkia, S. Posttraumatic growth in the wake of COVID-19 among Jewish and Arab pregnant women in Israel. Psychol. Trauma 2022, 14, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, V. Uncertainty and Successful Ageing: The Perspective from Malaysian Middle-Aged Adults Using Constructivist Grounded Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2019; pp. 1–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzhetska, M.S.; Kirzhetskyy, Y.I.; Kohyt, Y.M.; Zelenko, N.M.; Zelenko, V.A.; Yaremkevych, R.V. Peculiarities of tolerance to uncertainty of people in late adulhood as a factor affecting mental well-being. Wiad. Lek. 2022, 75, 1839–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Newton, J.; Copnell, B. Posttraumatic growth experiences and its contextual factors in women with breast cancer: An integrative review. Health Care Women Int. 2019, 40, 554–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Kim, N. Comparison of perception of successful aging between late middle-aged breast cancer survivors and healthy women. J. Korean Gerontol. Nurs. 2017, 19, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsungur, F. Gerontechnological factors affecting successful aging of elderly. Aging Male 2020, 23, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | Mean (±SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52.47 (±8.23) | |

| Treatment period (months) | 34.46 (±25.95) | |

| Religious | Yes | 80 (55.9%) |

| No | 63 (44.1%) | |

| Employed | Yes | 68 (47.6%) |

| No | 75 (52.4%) | |

| Activity ability | Asymptomatic | 89 (62.2%) |

| Symptomatic but fully functional | 54 (37.8%) |

| Successful Aging | Post-Traumatic Growth | Resilience | Intolerance of Uncertainty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-traumatic growth | 0.708 *** | |||

| Resilience | 0.463 *** | 0.318 *** | ||

| Intolerance of uncertainty | −0.282 *** | −0.155 (0.063) | −0.350 *** | 1 |

| Mean | 2.71 | 3.38 | 2.99 | 2.31 |

| SD | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.55 |

| Unstandardized Coeff. | SE | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | Standardized Effect | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.539 | 0.051 | 0.439 | 0.639 | 0.762 | <0.001 |

| Direct effect | 0.467 | 0.050 | 0.368 | 0.566 | 0.661 | <0.001 |

| x→ m1 → y | 0.057 | 0.020 | 0.023 | 0.102 | 0.073 | |

| x → m2 → y | 0.006 | 0.009 | −0.009 | 0.027 | 0.007 | |

| x → m1 → m2 → y | 0.009 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.023 | 0.011 | |

| Total indirect effect | 0.072 | 0.024 | 0.029 | 0.122 | 0.092 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yi, S.J.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, H. Effects of Post Traumatic Growth on Successful Aging in Breast Cancer Survivors in South Korea: The Mediating Effect of Resilience and Intolerance of Uncertainty. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212843

Yi SJ, Kim KS, Lee S, Lee H. Effects of Post Traumatic Growth on Successful Aging in Breast Cancer Survivors in South Korea: The Mediating Effect of Resilience and Intolerance of Uncertainty. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212843

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Su Jeong, Ku Sang Kim, Seunghee Lee, and Hyunjung Lee. 2023. "Effects of Post Traumatic Growth on Successful Aging in Breast Cancer Survivors in South Korea: The Mediating Effect of Resilience and Intolerance of Uncertainty" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212843

APA StyleYi, S. J., Kim, K. S., Lee, S., & Lee, H. (2023). Effects of Post Traumatic Growth on Successful Aging in Breast Cancer Survivors in South Korea: The Mediating Effect of Resilience and Intolerance of Uncertainty. Healthcare, 11(21), 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212843