Resources and Obstacles of a Maternity Staff Facing Intimate Partner Violence during Pregnancy—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Current Evidence

3. Importance of a Prevention-Based Global Approach

4. Aim and Value of Study

5. Materials and Methods

6. Ethical Design

7. Selected Cases Information

8. Participants

9. Analysis Methods

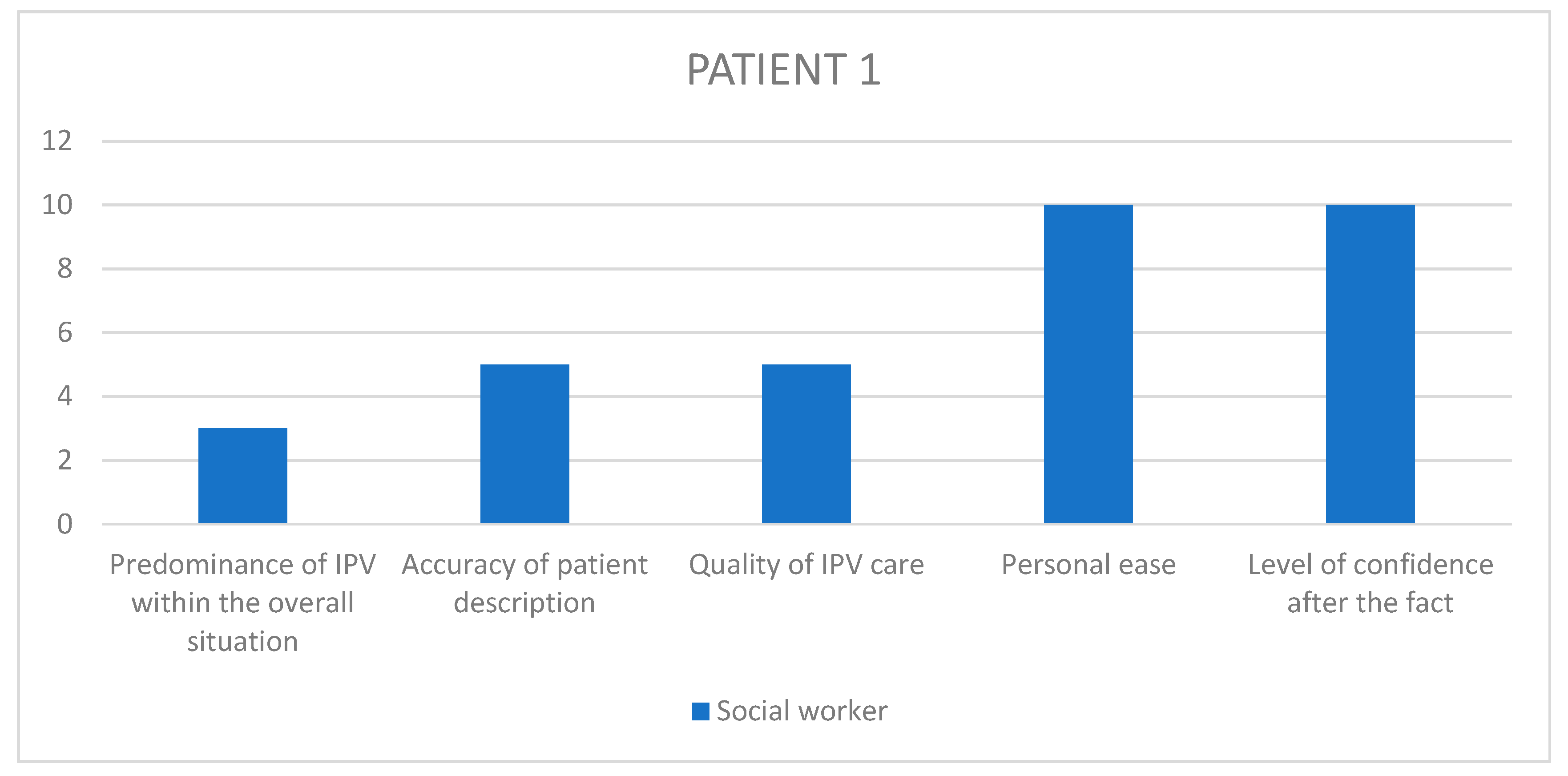

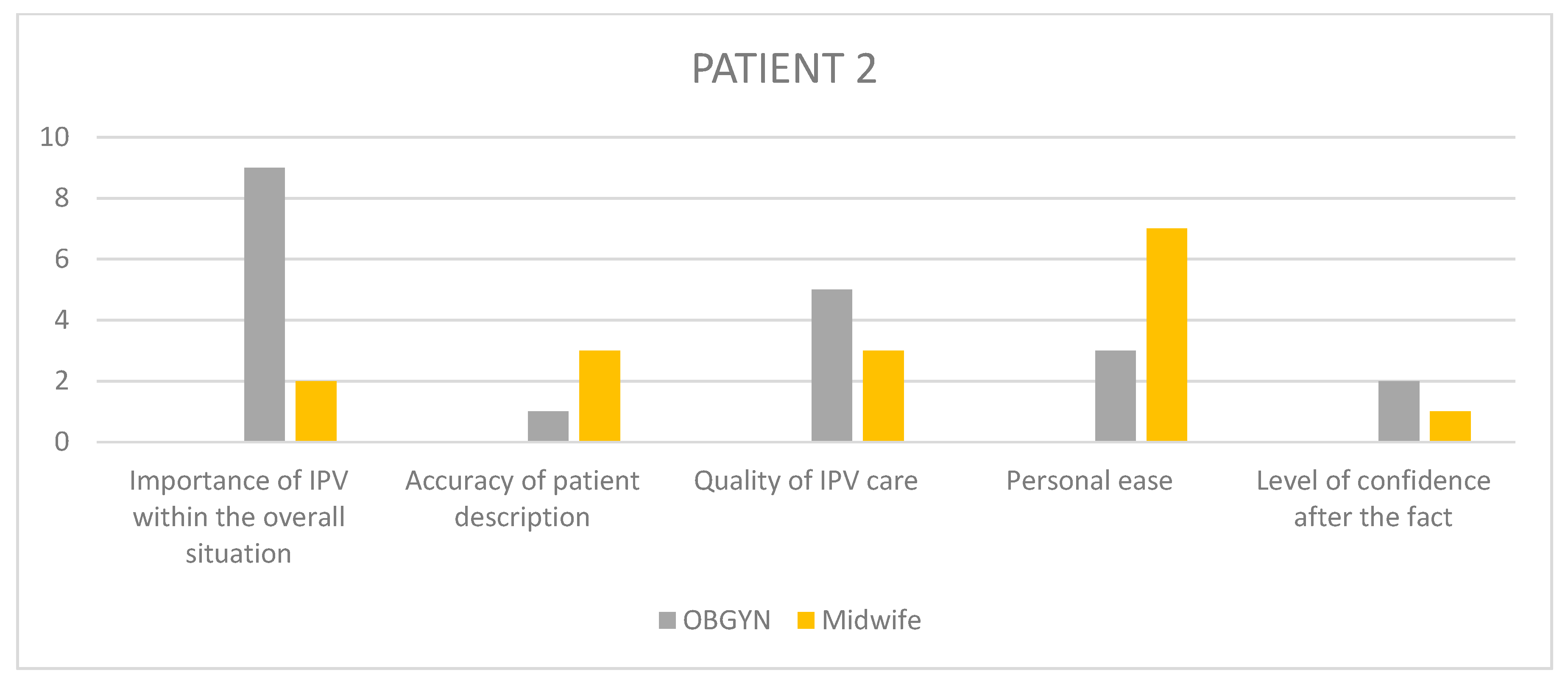

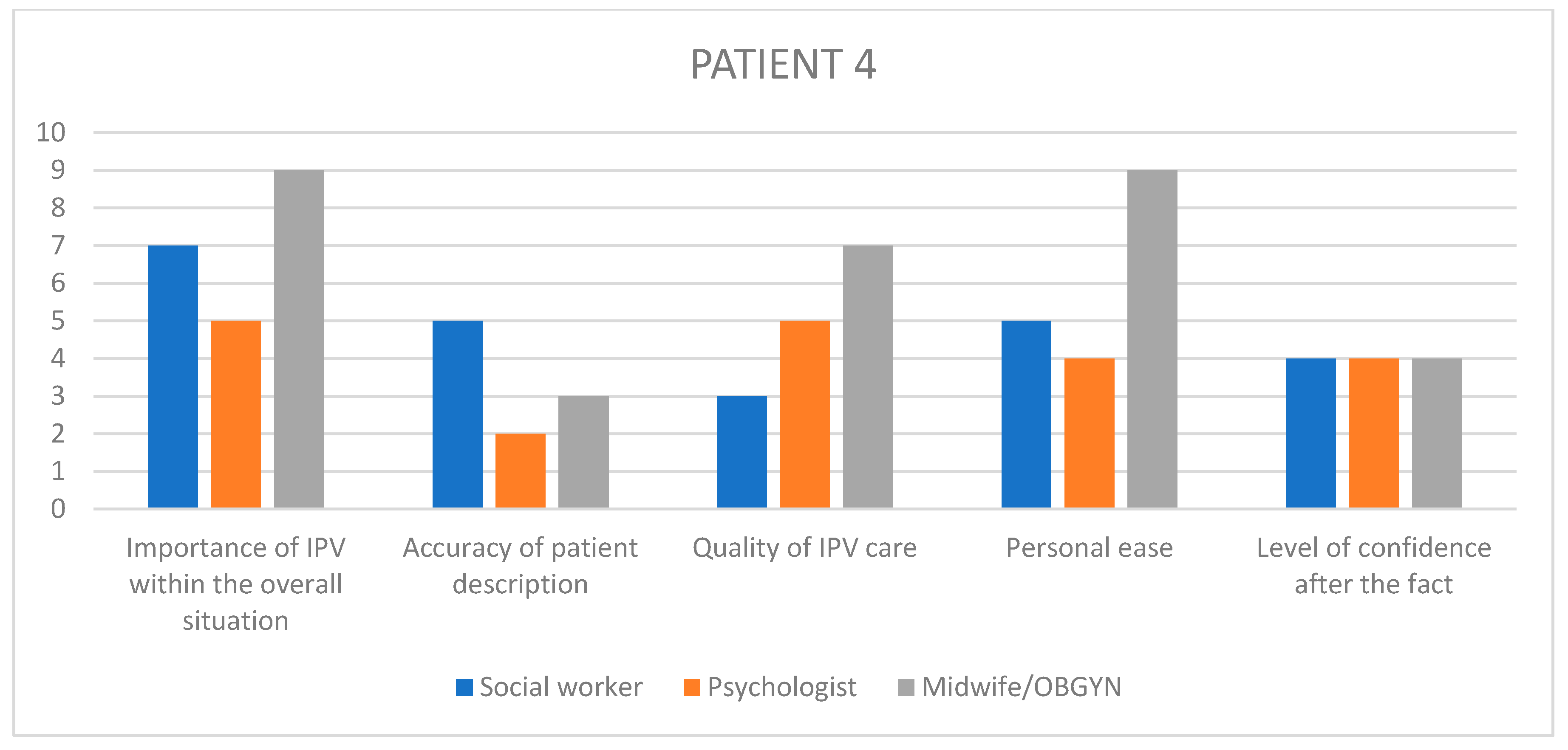

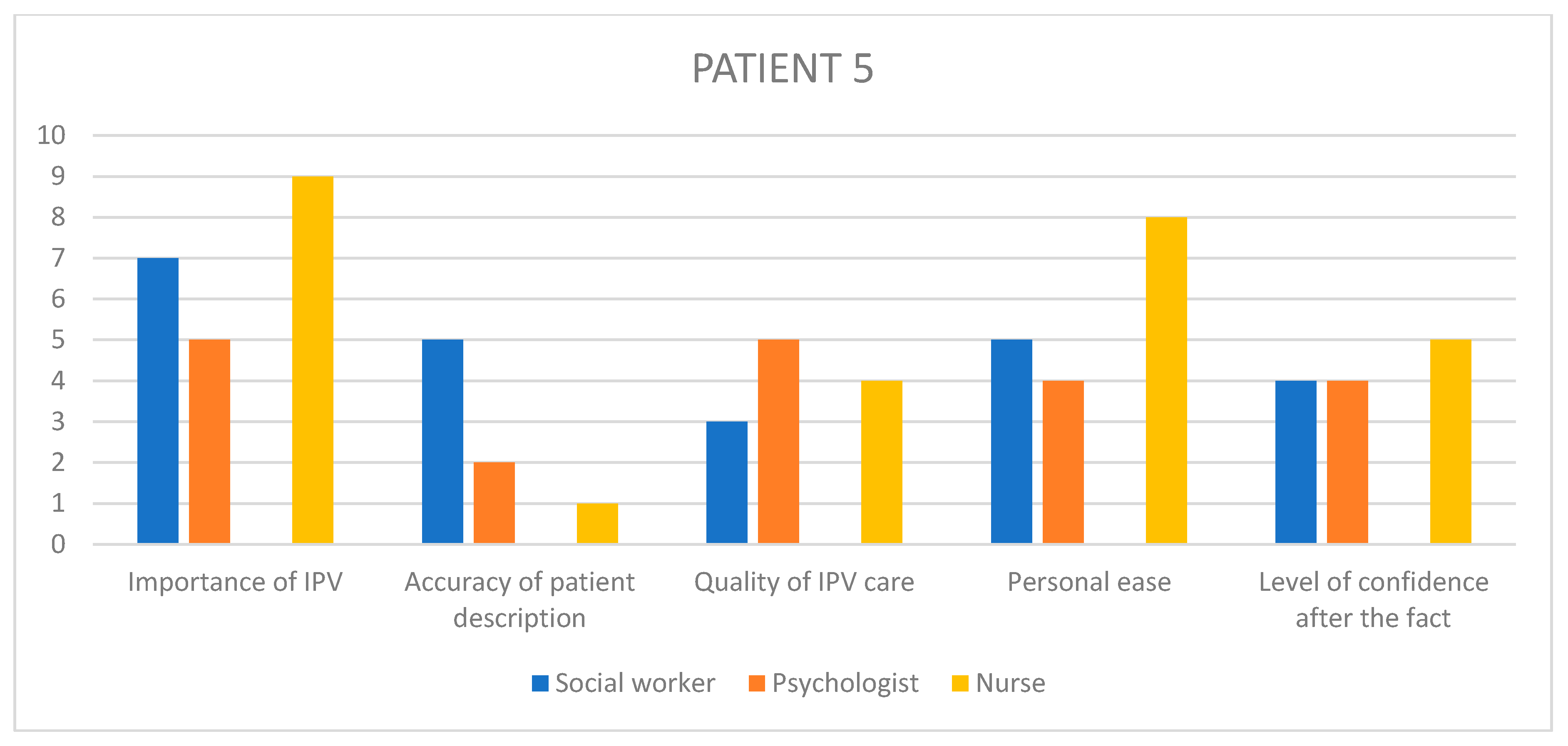

9.1. Analysis of Likert Scale

9.2. IPA

10. Results

10.1. Likert Scale Answers

10.2. IPA Results

10.2.1. Addressing the Issue

A: I don’t beat around the bush, I ask clear questions. Have you ever suffered physical or psychological acts of violence? Oftentimes, when I say psychological they ask me to explain what I mean by that, which is when I bring up the children if they have any, like have they ever seen anything… in any case, I make it really clear.

I: I always have if they’ve ever experienced any type of violence at any point in their life. I think I ask the question calmly, looking the patient in the eyes, I take my time.

B: Usually I start with a much broader question, I ask the patient if she has a support system to rely on during the pregnancy and after birth

D: It is like dropping a stone into a deep well and looking for the echo, simple things such as “how are things with your partner”, getting them to open up about the relationship history which makes sense when discussing pregnancy.

E: So I enquire about both past and present abuse. But I have a double-edged strategy, that starts with these most generic questions and then at some point goes into how secure the patient feels when thinking about going back home with the baby, is the father going to be supportive, if there are highs and lows, how far do the lows go…

I: Sometimes the answer lies in how people answer the question. Patients who answer yes to being victims of abuse usually take time to reflect on the question, whereas patients who say no can sometimes be a bit too quick, too abrupt, it is like a “no” of convenience.

B: What I say is, “I’m asking all those questions because it is important for me to get to know you so that I can better support you in your administrative endeavours, you don’t have to answer if you don’t want to and in no way am I trying to nag or pry, nor to make you uneasy in any way, really my purpose is to be as efficient as possible while assisting you

E: “Through my eyes, it seems like you’re going through something that can have many negative consequences on your health, and I believe the best thing to do to maintain your health would be (…), but I can’t put myself in your shoes, these choices are yours to make and whenever you feel good to go, if ever, we would help you through it, but it would be your own decision.

10.2.2. Warning Signs

F: The pain in the a** patient, the one everyone calls insufferable, who’s always asking for something, in the emergency room every five minutes, with demands that don’t make sense… or the one who’s always late.

E: Patient with a history of preterm labor, frequent bleeding, small babies at birth, or pregnancies that weren’t followed up on well enough or the classic late term pregnancy discovery. Patients with plenty of chronic illnesses that aren’t properly monito red, or patients labeled as “psychiatric” even though nobody was able to figure out an actual diagnosis.

B: It is very precious that the resident sounded the alarm as early as she did, I think she was accurate picking up on signs of vulnerability

E: Sometimes workers are obligated to start over and tackle the question with a patient when they’ve already been briefed on the situation by previous colleagues, which is not that easy

10.2.3. Finding Support and Betterment through Teamwork

C: I didn’t go into too much detail because the social worker had just been there and I know she had formally investigated the spousal violence aspect, all of that.

I: I had asked around beforehand, I had gone to see the psychologist and social worker to learn about what to and not to say, so her care protocol could be as homogenous as possible and also so that we could somehow officialise what she was saying to us

C: We had lawyers come to the maternity ward, explaining proper protocols, giving us insight on how certain situations should be handled, so we would be more at ease

D: I was lucky enough to work with highly trained midwives, who were solid pillars to stand on (…) they had also shared ways to formulate basic questions

G: I would always involve the social worker, they were the service designed to shed some light for us.

D: It is not easy, when you’re so young a doctor—I think she was well supported by the entire team, and the chief really stepping up into her position of authority.

10.2.4. Obstacles

E: We’re all familiar with this but it is still frustrating, feeling like we would want to go way faster than the patient does

D: It is like I identify with the baby and beg for protection before it can.

I: Sometimes, I don’t know why, we just forget about it. Sometimes you feel up to asking the questions, other times we sort of brush over it when we probably linger on the question for longer.

It is a super difficult situation to deal with for a doctor. It is hard to witness the violence people live, it is always… well it is empathy. Maybe it is got to do with identifying with the patient.

F: These are painful situations, so I think I have a tendency to put them aside in my head as soon as I can, because of how psychologically burdening they are.

C: We all know the hardest patients situations are also the hardest to handle for HCPs

A: I can’t believe this wasn’t common knowledge amongst everyone on the case, I am shocked.

I: Since I only focus on the medical side, I might have false information.

F: Sometimes there are so many people working on the same case that I feel like if everyone brings up spousal violence over and over again, the patient might feel like they are not anything more than the abuse, and that’s counterproductive

F: In the end, nobody really dove into the situation because everyone was ill at ease and thought it was not their call to make because the next person would probably tackle it better.

F: They get so tricky that in the end nobody has a clue how to actually care for them.

A: This is a problem, the structure itself is so big that there are indeed connections between us, but they are hard to find, hard to hold on to.

C: I found there was a lot of judgemental projections in this family, and I spent the week trying to add some perspective to the mix. I thought, would it be too hard to just hold a well-intentioned attitude towards them.

C: It was like a runway of HCPs one after the other, just because the interpreter was here. Midwife, then pediatrician, then social worker, and I showed up in the middle of all of that.

10.2.5. Decrypting the Silence

C: It was mostly… the silences that came after anything she would share. She had a sort of… silent pout, that I interpreted a being a sign of suffering but at the same time, acceptance of a fatality that she would have to learn to live with that suffering.

E4: Consultations were very long because there were moments where she would share something and right after that be all withdrawn and silent, she’d look at me saying “I shouldn’t have told you”.

F: These patients can be in absolute mutism.

F: She hadn’t set foot outside in a week, even when we offered she went for a breath of fresh air. She said, word for word “I’ll try and make it to the hallway”, when the time came for her to leave the ward. It was a way for her to express how difficult it was for her to move forward, to go outside. But it was really physical.

C: It was surprising, given the surgery she’d just gone through, she was on her feet really fast, she didn’t look ill at all, she just wanted out.

H: As time went on, she wouldn’t realize her refusal was putting the baby in danger, she couldn’t be reasoned with.

I: After all, delaying care for so long had gravely endangered her baby’s health, as well as her own.

A: From the very first consultation she alleged not seeing any interest in meeting with me.

C: Sometimes I try and flip the question around, I say “do you know what you’re seeking by coming here”.

10.2.6. The Balance of Benefit and Trust

A: And providing social security rights creates some kind of trust, it directly benefits her day to day life, and that makes for more regularity in attending consultations, and over time, that’s how you feel able to tackle some questions.

B: The administrative side of things might not seem all that interesting, but it allows us to build a very solid patient rapport and move forward from there.

F: You can feel it, when patients sort of latch onto you, you become somewhat of a reassuring attachment figure, it was obvious we had a special kind of bond

A: The patient was from the Caribbean, her mother was white so it is weird, but she and I sort of looked alike.

I: Sometimes patients feel comfortable when we ask about violence because it feels nice to them that we cared enough to ask…

10.2.7. Inauthenticity in the Patient’s Speech: Spreading Confusion or Expressing Ambivalence

A: Discourse can be sort of empty, bland, distant, on very important subjects. (…) She could have completely different standpoints questioning the entire care she had received and I started to get worried, having this discrepancy between the real reasons why she was hospitalized and the stance she was taking in her mother’s presence.

C: I think there were times where she regretted having told us some things. She actually said it clearly. “Yes, he’s very nice, forget everything I said before”

B: At first she didn’t want to live with him, then she changed her mind, and I wasn’t too keen on that, which she ended up holding against me in the end

10.2.8. When Keeping a Secret Reaches the Extreme

C: The entire conversation was centred on the fact that she felt imprisoned in the ward, that she hated it, that she wanted out at soon as possible.

D: She had been given a mission not to get along with me.

D: (About the altercation between the patient’s mother and the paediatrician) I know it escalated to insults, she said “bitch”, I know the poor paediatrician was so traumatized she wasn’t sure what she had heard.

10.2.9. Pregnancy and Timing

B: It is true that pregnancy all the way to childbirth is not a banal time in a woman’s life, it is kind of a turning point—I feel like it is all or nothing. Sometimes that’s when a woman will decide to come clean about everything, we hear that quite often, like “it is the first time I’ve ever said anything about this”.

E: Some patients place a lot of hope in their current pregnancy, therefore even right at the beginning of the pregnancy it’ll be time for them to confide, I think

B: These are patients where in the beginning of the pregnancy they’ll be on their guard, they’ll still be stuck, and they are at risk of dropping out of care completely so it is complicated. And at the end they’ll be resigned, fatalistic, vulnerable with childbirth getting closer, and that’s even more complicated. So there’s sort of a period of light in the middle of pregnancy I believe.

D: I think the baby has to be present enough in the woman’s psyche, there needs to be transparency… I think there needs to be active foetal movement, basically.

B: Sometimes I think that all you need is something happening 2 s before the consultation for her to decide she doesn’t want to discuss it at all. Maybe the partner will have sent a text right then and there, so it is like all is well, do you get it? Like, it could be the right time one second, and the wrong time the next.

E: There might be moments of crisis which might get them to the point of filing a complaint, like that will be the right moment just like that. I don’t feel like there’s a specific timeframe more comfortable than another, apart from those crisis events.

D: It can be just because of that one event pushing them over the limit.

D: (Referring to sharing risk ratios for adverse events in children after gestational

IPV) With women who have a tendency to over intellectualize, it can be really helpful to share these numbers because it sort of pulls them out of their day-to-day acceptance

D: For her baby though, if she thinks her baby might be in danger, if she’s unhappy at home or meets that one professional with whom there’s a good rapport, I think she could try and find a way out

C: Her speech was pretty transparent, that she hadn’t wanted this pregnancy, that she never wanted to be pregnant again, and that she was actually relieved that the hysterectomy had happened because that meant no more pregnancies.

C: In the patient’s discourse, it is often linked to a notion of not wanting to deprive their child of a fatherly presence. It has to do with these idealized representations of a mum, dad, baby nuclear family. And maybe it is also rooted in the fact that at this time, imagining themselves raising a baby alone triggers too much anxiety for them.

C: He had completely isolated her, she lived secluded from her family and just kept having his babies.

10.2.10. The Baby Fadeout Phenomenon

G5: It was something growing inside her belly. It wasn’t a being.

C3: I was startled by the interactions I witnessed in the mother-infant unit. She barely had any discourse about her baby, didn’t show any sign of concern about her, in a sort of denial of the needs of a premature baby who needed intention, a specific kind of care… she mostly called her “that one” instead of her name.

B: Her daughter’s wellbeing... No, it came and went, wasn’t very present in her mind. Actually, we told her many times with the midwife, «come on, think of “baby’s name”

D: Parents who don’t feel guilty when something alerts the care system is always worrisome in a way, at least in the sense of negligence which still is a form of violence albeit a relatively passive form

C: She was a very tiny baby, who barely put on any weight, she was very sleepy. I don’t know if we can call it withdrawal at this point, but she didn’t feel very present in the moment, she wasn’t making any progress in her ability to feed, etc.

10.2.11. Noticing Maternal Override

I: The grandmother doing skin to skin contact with the newborn, that’s not usual

C: She kept referring to a higher power that had complete authority over her (…) it was like something didn’t belong to her anymore, that could be due to her husband, there was an obvious dynamic of domination. Like being dispossessed of her own life.

D: She gave birth to her mother’s baby.

10.2.12. Cultural Awareness

A: Really, this is something frequent with African mothers, having the family’s support, welcoming the newborn as a family with the aunt, the grandmother present

E: She said, “because now we’re a family” meaning that the traditional wedding implied a common living situation

G: Sometimes during group sessions we heard mothers finally allowing themselves to say, “midwives are telling me I should bathe my baby a certain way and I don’t dare to tell them that I’ve already had four kids in my country and I always did it differently, but I’m afraid they’ll decide that I’m not capable, that I don’t do things properly just because I do things our way”.

E: It was obvious it meant a lot to her, to her there were principles to uphold, an order to abide by.

10.2.13. Respecting Boundaries

D: I’ll always tread lightly. These are situations where if you kind of bust in, doors close and that’s very counter productive.

F: They are perfectly allowed not to share anything about themselves with us

10.2.14. Personal Experience over Factual Evidence

F: If it is a patient who’s doing the work, who has no issue talking about it, etc. I think we have to de-taboo the situation and collect it as we would with any other past history event

A: My intern really wanted to see what had been cited in the complaint. I thought to myself, right now with this patient, I really didn’t need to see that. I needed the patient herself to tell me what she’d gone through, how she’s experiencing things at this moment.

C: Sometimes I realize that if I get stuck in factual facts, that can bring up a lot of resistance on the part of the patient, or in any case a sort of “cancellation” of the events. I’d say it is better to go forward angling your questions on what the patient’s experience of the relationship, offering an ear to their feelings rather than asking them to unravel facts.

10.2.15. Giving Back Control

E: These are people who’ve always been brought down, whose choices were never taken into account, or their desires either, and it is not our place to put them through that again.

F: (About deciding to give the baby up for adoption) I try and remind them that the decision they took is a mother’s decision, that it is a brave decision and that they should feel proud of themselves in their mothering role: like, being a mother doesn’t have to be the imagined scenario of giving birth and going home with a baby, sometimes it is making tough calls in order to really protect the baby. That’s acting like a proper mother.

E: We gave her all the time and space to do whatever she wanted, we said that in any case we’d always support her no matter what choice she makes.

F: We gave her freedom to take all the time she needed, no matter how frustrating it was for us

11. Discussion

11.1. HCPs’ Distorted Perception of Their Quality of Care

11.2. A Dual Purpose: Creating Personal and Institutional Trust

11.3. Strengths and Limitations

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Alhusen, J.L.; Ray, E.; Sharps, P.; Bullock, L. Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy: Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes. J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, C.K.; Gilmore, A.K.; Aguayo, R.O.; Rheingold, A.A. Perinatal Intimate Partner Violence. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnbogadóttir, H.; Torkelsson, E.; Christensen, C.B.; Persson, E.-K. Midwives experiences of meeting pregnant women who are exposed to Intimate-Partner Violence at in-hospital prenatal ward: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Midwifery 2020, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacchus, L.; Mezey, G.; Bewley, S. A Qualitative Exploration of the Nature of Domestic Violence in Pregnancy. Violence Against Women 2006, 12, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgendorf, M.A. Intimate Partner Violence and Women’s Health. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Gálvez, R.M.; Martín-Peláez, S.; Martínez-Galiano, J.M.; Khan, K.S.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in Pregnancy: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm, C.A.; Bullock, L.; Ferguson, J.E. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy: Epidemiology and impact. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankerstjerne, L.B.S.; Laizer, S.N.; Andreasen, K.; Normann, A.K.; Wu, C.; Linde, D.S.; Rasch, V. Landscaping the evidence of intimate partner violence and postpartum depression: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Gálvez, R.M.; Martín-Peláez, S.; Fernández-Félix, B.M.; Zamora, J.; Khan, K.S.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A. Worldwide Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in Pregnancy. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 738459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, L.C.; Stewart, D.E.; Vigod, S.N. Intimate Partner Sexual Violence: An Often Overlooked Problem. J. Women’s Health 2019, 28, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Silva, R.; Leite, F.M.C. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors. Rev. Saude Publica 2019, 54, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusen, J.L.; Lucea, M.B.; Bullock, L.; Sharps, P. Intimate Partner Violence, Substance Use, and Adverse Neonatal Outcomes among Urban Women. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhateeb, R.; Abdelmeged, A.; Ahmad, S.; Mahran, A.; Abdelzaher, W.Y.; Welson, N.N.; Al-Zahrani, Y.; Alhuwaydi, A.M.; Bahaa, H.A. Impact of domestic violence against pregnant women in Minia governorate, Egypt: A cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memiah, P.; Cook, C.; Kingori, C.; Munala, L.; Howard, K.; Ayivor, S.; Bond, T. Correlates of intimate partner violence among adolescents in East Africa: A multi-country analysis. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bramhankar, M.; Reshmi, R.S. Spousal violence against women and its consequences on pregnancy outcomes and reproductive health of women in India. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.R.; Maxwell, D.; Williams, J.R. Qualitative, Interpretive Metasynthesis of Women’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2019, 48, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Moreno, G.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Henares-Montiel, J.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Higueras-Callejón, C.; Ricci-Cabello, I. Intimate partner violence and perinatal health: A systematic review. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartland, D.; Conway, L.J.; Giallo, R.; Mensah, F.K.; Cook, F.; Hegarty, K.; Herrman, H.; Nicholson, J.; Reilly, S.; Hiscock, H.; et al. Intimate partner violence and child outcomes at age 10: A pregnancy cohort. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.P.; Emond, A.; Ludermir, A.B. Depression in childhood: The role of children’s exposure to intimate partner violence and maternal mental disorders. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 122, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, C.A.; Bullock, L.; Ferguson, J.E. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy: Screening and intervention. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, Y.; Imazeki, M. Experiences of being screened for intimate partner violence during pregnancy: A qualitative study of women in Japan. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eustace, J.; Baird, K.; Saito, A.S.; Creedy, D.K. Midwives’ experiences of routine enquiry for intimate partner violence in pregnancy. Women Birth 2016, 29, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physical Violence | Includes the intentional use of physical force with the potential to cause death, disability, injury or harm. |

| Sexual Violence | Includes forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act, sexual touching, or a non-physical sexual event (e.g. sexting) without the victim’s freely given consent, including cases in which the victim is unable to consent as a result of being too intoxicated through voluntary or involuntary use of alcohol or drugs |

| Stalking | A pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact with a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim |

| Psychological Aggression | The use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to harm a partner mentally or emotionally and/or to exert control over a partner |

| Can you describe your job and function within the maternity ward. |

| How would you describe your knowledge of GIPV and its consequences? How often are you faced with such situations? |

| Is IPV a topic you usually bring up in consultations? |

| What are your personal strategies to initiate dialogue regarding potential IPV for the first time? And how do you follow up? |

| In your opinion, at what time of the pregnancy is it more pertinent to ask about potential IPV, in order to gather accurate information as well as securing the therapeutic relationship? |

| Case-specific questions |

| Can you retell the story of this patient based on your own memories? What were the most important elements? |

| Can you describe the context in which you first met with the patient? |

| What were the first signs that alerted you to the potential presence of IPV? |

| How could you describe the patient’s reaction to this subject? |

| Did you feel like you had to avoid certain questions, are there questions you wish you had asked? |

| How did you engage with the perpetrator, if you encountered them? |

| What difficulties did you encounter in this case, if any? What would you have needed to overcome them? |

| GIPV was at the forefront… secondary… minimal aspect of the overall pathology |

| The patient initially described their experience in a minimized… accurate… exaggerated manner |

| In my opinion, we provided insufficient… sufficient… disproportionate attention to the violence aspect of their pathology |

| During the course of treatment, I felt helpless… limited… efficient in my caregiving ability |

| After the fact, I feel pessimistic… preoccupied… reassured regarding the future of the mother and infant |

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 27 | 43 | 30 | 26 | 17 |

| Origin | Africa | Western Europe | Eastern Europe | Africa | Mixed Caribbean |

| Status | Clandestine | National | Documented | Asylum seeker | National |

| Employment | None | NR | None | Previous | NA |

| Education | NR | NR | NR | University | High School |

| Marital status | Married separated | Separated | Married | Married | Celibate |

| Medical History | None | Hypertension Depression | Obesity | Excision Traumatic hearing loss | None |

| Reproductive history | None | Fetal death Stillbirth Prematurity Fetal death Prematurity Prematurity | 7 on-term live births | None | None |

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desire for pregnancy | NR | Unplanned Undesired | Planned Desired | Unplanned | Unplanned |

| Term of discovery | 14w | 31w | NR | 20w | 12 |

| Hospitalization | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Maternal complication | No | Preeclampsia Kidney failure | P. accreta | None | Pre eclampsia |

| Fetal complication | None | IUGR | None | None | IUGR |

| Term of labor | 37 | 31 | 35 | 41 | 36 |

| Labor details | Emergency C section Hemorrhage | Emergency C section | Planned C section Severe Hemorrhage Kidney failure | Spontaneous physiological labor | Induced labor |

| Newborn | Healthy twins | Low birth weight Prematurity | Induced prematurity | Low birth weight | Induced prematurity Low birth weight |

| Postpartum | Normal | Recuperation | Recuperation | Normal | Early discharge |

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author of violence | Husband (separated) | Ex-partner | Husband (current) | Husband (current) Family | Mother |

| Duration | 18 months | Over 6 years | Unreported | Lifelong | Unknown |

| Type | |||||

| Physical | x | x | x | ||

| Psychological | x | x | x | x | x |

| Verbal | x | x | x | ||

| Sexual | x | ||||

| Complications | Severe obstetrical events | Isolation Withholding care | Excision Post traumatic hearing loss | Isolation Coercion Withholding care | |

| Outcome | Fled home | Separated | Loss of touch with health care system | Separation | Loss of touch with health care system CPS notification |

| A | B | C | D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profession | Social worker | Social worker | Psychologist | Psychologist | |

| Time in the maternity | 10 years | 8 years | 8 years | 4 months | |

| Previous employment | No | Other ward (Non OB) | No | Yes (1 year) Other OB ward | |

| Initial Ipv training | Basic | Basic | No | No | |

| Further theoretical IPV training | Yes (thesis) | No | No | Yes (Seminars) | |

Timeframe

| |||||

| +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| ++ | ++ | ||||

| + | ++ | + | ++ | ||

| Met with | Pat. 1 Prenatal | Pat.4 Prenatal Postnatal | Pat. 4 Prenatal Perinatal | Pat. 5 Postnatal | |

| Pat. 5 Prenatal Postnatal | Pat. 3 Postnatal | ||||

| E | F | G | H | I | |

| Profession | Midwife | Midwife | Nurse | Pediatrician | OBGYN |

| Time in the maternity | 3 years | 4 years | 1 year | 19 years | 2.5 years |

| Previous employment | No | No | Yes | Unknown | Yes (part-time) Other OB ward |

| Initial Ipv training | Basic | Basic | No | No | No |

| Further theoretical IPV training | Yes (Diploma) | No | No | No | Specific training |

Timeframe

| |||||

| +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | |

| +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ | |

| ++ | + | ++ | +++ | + | |

| Met with | Pat. 4 Prenatal Perinatal Postnatal | Pat. 2 Perinatal Postnatal | Pat. 5 Prenatal | Pat. 5 Postnatal | Pat. 2 Perinatal Postnatal |

| PATIENT 1 | PATIENT 2 | PATIENT 3 | PATIENT 4 | PATIENT 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| B | 7 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| C | 7 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| D | 9 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| E | 9 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| F | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| G | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I | 9 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sureau, Y.; Moro, M.-R.; Radjack, R. Resources and Obstacles of a Maternity Staff Facing Intimate Partner Violence during Pregnancy—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202782

Sureau Y, Moro M-R, Radjack R. Resources and Obstacles of a Maternity Staff Facing Intimate Partner Violence during Pregnancy—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(20):2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202782

Chicago/Turabian StyleSureau, Yam, Marie-Rose Moro, and Rahmeth Radjack. 2023. "Resources and Obstacles of a Maternity Staff Facing Intimate Partner Violence during Pregnancy—A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 11, no. 20: 2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202782

APA StyleSureau, Y., Moro, M.-R., & Radjack, R. (2023). Resources and Obstacles of a Maternity Staff Facing Intimate Partner Violence during Pregnancy—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 11(20), 2782. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202782

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)