The Development of a Communication Tool to Aid Parent-Centered Communication between Parents and Healthcare Professionals: A Quality Improvement Project

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How can we support parents to feel empowered to communicate their values and priorities to HCPs?

- What format should a communication tool take?

- How does the communication tool work in clinical practice?

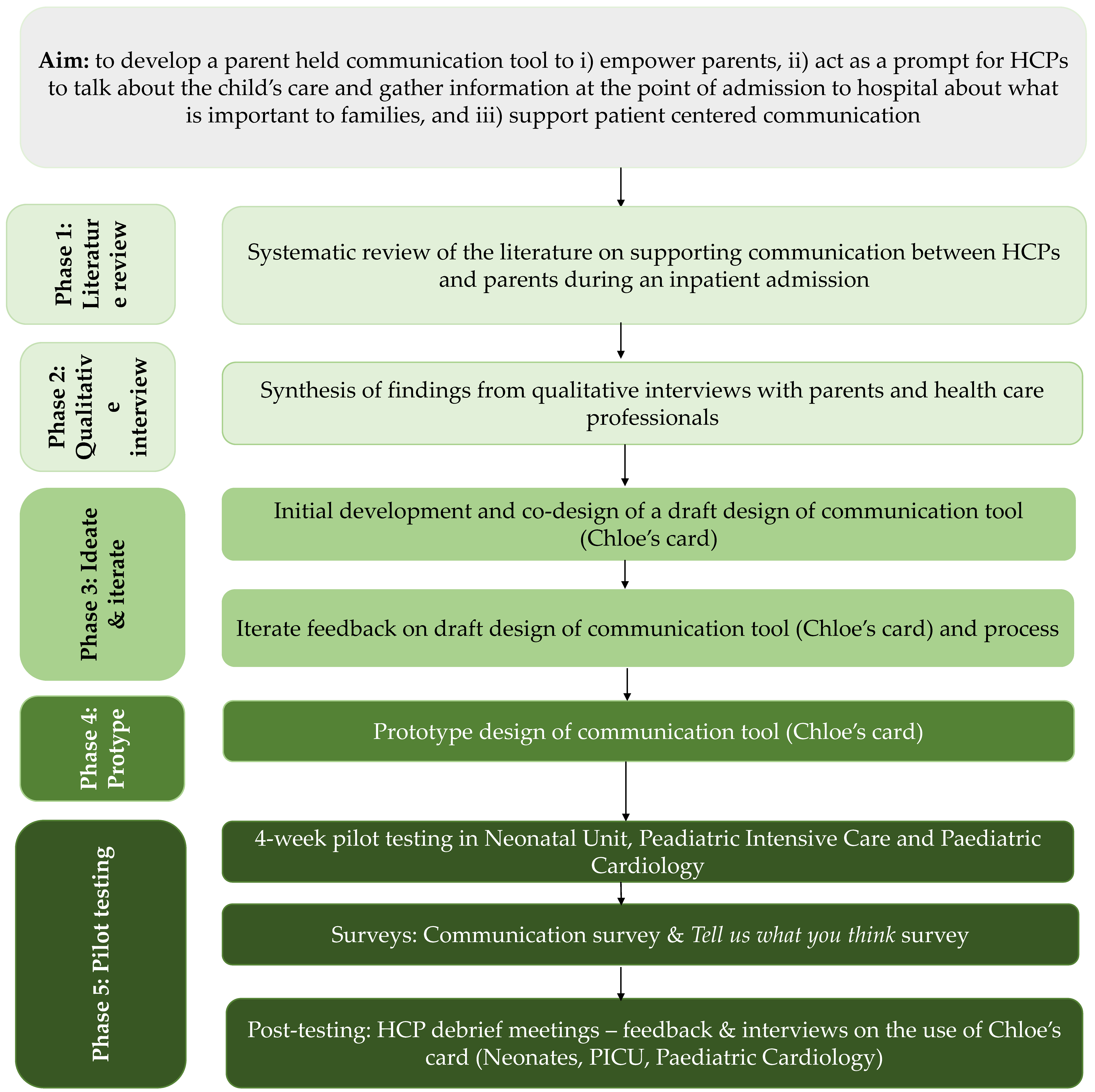

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Developing and Designing the Intervention

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Design Thinking

3.1. Phase 1: Literature Review

Results

3.2. Phase 2: Define—Qualitative Interviews

3.2.1. Interviews between Parents and Healthcare Professionals

Healthcare Professionals’ Interviews on Factors Influencing Parents Experiences of Communication

- (i)

- Location of conversations

- (ii)

- Communication to support transition between an intensive care unit and step down-ward

- (iii)

- Communication between healthcare professionals and parents

- (iv)

- Avoidance of conflicting messages from healthcare professionals to parents

- (v)

- Feeding related communication

3.2.2. Communication—Parents

Parental Experiences and Needs around Communication

- (i)

- Being listened to

- (ii)

- Having a clear explanation of what is happening

- (iii)

- Involvement in decision making

- (iv)

- Choices around feeding

Impact of Poor Communication—Parents and Healthcare Professionals

- (i)

- Lack of control

- (ii)

- Feeling unprepared

- (iii)

- Loss of a role as a parent

- (iv)

- No choices around feeding and loss of maternal status

3.3. Phase 3: Ideate and Iterate

3.4. Phase 4: Develop the Prototype

3.4.1. Parents—Card

3.4.2. HCP—Card

3.5. Phase 5: Pilot Testing of Chloe’s Card

3.5.1. Testing the Intervention—Surveys

3.5.2. Outcome Measures

3.5.3. Preparation for Testing

Staff training

Promotion of the intervention

During the testing period

Debrief following the testing period

3.6. Results of the Testing Phase

3.6.1. Feedback on Chloe’s Card

The Idea Is Attractive

Perceptions of Good Communication

Adding to the ‘List of Stuff’ to Do?

Who and What Are We Targeting?

Appearance and Content of the Card

3.6.2. Moving Forward

Empowerment Tool for Parents

Creating Space for a Conversation

A flexible Simplified Process

Clear HCP Follow up

3.6.3. Communication with Health Care Professionals

3.6.4. Parents and HCPs Views of Chloe’s Card

4. Discussion

4.1. Impliactions for Practice and Future Research

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McSherry, M.L.; Rissman, L.; Mitchell, R.; Ali-Thompson, S.; Madrigal, V.N.; Lobner, K.; Kudchadkar, S.R. Prognostic and Goals-of-Care Communication in the PICU: A Systematic Review. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 2, e28–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer| Guidance| NICE. 2004. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg4 (accessed on 4 May 2023).

- Leonard, P. Exploring ways to manage healthcare professional—Patient communication issues. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, W.; Abdelmageed, A. Understanding patient complaints. BMJ 2017, 356, j452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward-Kron, R.; FitzDowse, A.; Shahbal, I.; Pryor, E. Short Report: Using complaints about communication in the emergency department in communication- skills teaching. Focus. Health Prof. Educ. A Multi-Prof. J. 2017, 18, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Children and Young People’s Survey 2020—Care Quality Commission. Available online: https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/surveys/children-young-peoples-survey-2020 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Curtis, K.; Foster, K.; Mitchell, R.; Van, C. Models of Care Delivery for Families of Critically Ill Children: An Integrative Review of International Literature. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasparian, N.A.; Kan, J.M.; Sood, E.; Wray, J.; Pincus, H.A.; Newburger, J.W. Mental health care for parents of babies with congenital heart disease during intensive care unit admission: Systematic review and statement of best practice. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 139, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.L.; Pagel, C.; Ridout, D.; Wray, J.; Tsang, V.T.; Anderson, D.; Banks, V.; Barron, D.J.; Cassidy, J.; Chigaru, L.; et al. Early Morbidities Following Paediatric Cardiac Surgery: A Mixed-Methods Study; Health Services and Delivery Research; NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2020. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559562/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Landolt, M.A.; Ystrom, E.; Sennhauser, F.H.; Gnehm, H.E.; Vollrath, M.E. The mutual prospective influence of child and parental post-traumatic stress symptoms in pediatric patients. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Als, L.C.; Picouto, M.D.; Hau, S.-M.; Nadel, S.; Cooper, M.; Pierce, C.M.; Kramer, T.; Garralda, M.E. Mental and physical well-being following admission to pediatric intensive care. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 16, e141–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.; Davies, N.; Butterick, K.L.; Oswell, J.L.; Siapka, K.; Smith, C.H. Shared decision-making for children with medical complexity in community health services: A scoping review. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2023, 7, e001866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauchner, H. Shared decision making in pediatrics. Arch. Dis. Child. 2001, 84, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Jürgens, J.; Redaèlli, M.; Klingberg, K.; Hautz, W.E.; Stock, S. Impact of the communication and patient hand-off tool SBAR on patient safety: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streuli, J.C.; Widger, K.; Medeiros, C.; Zuniga-Villanueva, G.; Trenholm, M. Impact of specialized pediatric palliative care programs on communication and decision-making. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, L.; Graham, I.D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Jull, J.; Shephard, A.; Lawson, M.L.; Davis, A.; Yameogo, A.; Stacey, D. Barriers and facilitators of pediatric shared decision-making: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baenziger, J.; Hetherington, K.; Wakefield, C.E.; Carlson, L.; McGill, B.C.; Cohn, R.J.; Michel, G.; Sansom-Daly, U.M. Understanding parents’ communication experiences in childhood cancer: A qualitative exploration and model for future research. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4467–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doupnik, S.K.; Hill, D.; Palakshappa, D.; Worsley, D.; Bae, H.; Shaik, A.; Qiu, M.K.; Marsac, M.; Feudtner, C. Parent Coping Support Interventions during Acute Pediatric Hospitalizations: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20164171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.E.; Aslakson, R.A.; Long, A.C.; Puntillo, K.A.; Kross, E.K.; Hart, J.; Cox, C.E.; Wunsch, H.; Wickline, M.A.; Nunnally, M.E.; et al. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhl, T.; Fisher, K.; Docherty, S.L.; Brandon, D.H. Insights into patient and family-centered care through the hospital experiences of parents. J. Obs. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towle, A.; Greenhalgh, T.; Gambrill, J.; Godolphin, W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision makingCommentary: Competencies for informed shared decision makingCommentary: Proposals based on too many assumptions. BMJ 1999, 319, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, S.; Callahan, M.E.; Berlin, A. Patient Values: Three Important Questions-Tell Me More? Why? What Else? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 13, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskedal, L.T.; Hagemo, P.S.; Seem, E.; Eskild, A.; Cvancarova, M.; Seiler, S.; Thaulow, E. Impaired weight gain predicts risk of late death after surgery for congenital heart defects. Arch. Dis. Child. 2008, 93, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitting, R.; Marino, L.; Macrae, D.; Shastri, N.; Meyer, R.; Pathan, N. Nutritional status and clinical outcome in postterm neonates undergoing surgery for congenital heart disease. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 16, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L.V.; Magee, A. A cross-sectional audit of the prevalence of stunting in children attending a regional paediatric cardiology service. Cardiol. Young 2016, 26, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bry, A.; Wigert, H.; Bry, K. Need and benefit of communication training for NICU nurses. PEC Innov. 2023, 2, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, L.; Berta, W.; Cleverley, K.; Medeiros, C.; Widger, K. What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, M.F.; Iacob, E.; Reblin, M.; Ellington, L. Hospice nurse identification of comfortable and difficult discussion topics: Associations among self-perceived communication effectiveness, nursing stress, life events, and burnout. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolikowski, K.A.; Bi, M.; Baggott, C.M.; Khorzad, R.; Holl, J.L.; Kruser, J.M. Design thinking to improve healthcare delivery in the intensive care unit: Promise, pitfalls, and lessons learned. J. Crit. Care 2022, 69, 153999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirriyeh, R.; Lawton, R.; Gardner, P.; Armitage, G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: The development and evaluation of a new tool. J. Eval. Clin. Pr. 2012, 18, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feudtner, C. Collaborative communication in pediatric palliative care: A foundation for problem-solving and decision-making. Pediatr. Clin. North. Am. 2007, 54, 583–607, ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.J.; Whitehead, L.; Maybee, P.; Cullens, V. The parents’, hospitalized child’s, and health care providers’ perceptions and experiences of family centered care within a pediatric critical care setting: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. J. Fam. Nurs. 2013, 19, 431–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubauer, K.; Williams, E.P.; Donohue, P.K.; Boss, R.D. Communication and decision-making regarding children with critical cardiac disease: A systematic review of family preferences. Cardiol. Young 2018, 28, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, G.; Montgomery, H.; Eyre, C.; Cummins, C.; Pattison, H.; Shaw, R. Developing a Tool to Support Communication of Parental Concerns When a Child Is in Hospital. Healthcare 2016, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwame, A.; Petrucka, P.M. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: Barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janvier, A.; Barrington, K.; Farlow, B. Communication with parents concerning withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining interventions in neonatology. Semin. Perinatol. 2014, 38, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis-Larocque, G.; Williams, K.; St-Sauveur, I.; Ruddy, M.; Rennick, J. Nurses’ perceptions of caring for parents of children with chronic medical complexity in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2017, 43, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, L.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Adams, S.; Hepburn, C.M.; Cohen, E. A qualitative analysis of information sharing for children with medical complexity within and across health care organizations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarin, O.A.; Chesler, M.A. Relationships with the medical staff and aspects of satisfaction with care expressed by parents of children with cancer. J. Community Health 1984, 9, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkin, J.; Beaune, L.; Moore, C.; Weiser, N.; Arje, D.; Rapoport, A.; Netten, K.; Adams, S.; Cohen, E.; Amin, R. Toward an Understanding of Advance Care Planning in Children with Medical Complexity. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20192241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, M.; Moldovan, R.; Băban, A. Families with complex needs: An inside perspective from young people, their carers, and healthcare providers. J. Community Genet. 2022, 13, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, B.L.; Serna, R.W.; LaLumiere, M.; Rogal, M.; Foley, K.; Lombardo, M.; Manganello, C.; Pugh, V.; Veloz, A.; Solodiuk, J.C.; et al. Leveraging Parent Pain Perspectives to Improve Pain Practices for Children with Medical Complexity. Pain. Manag. Nurs. 2021, 22, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberne, L.M.; Fahner, J.C.; Sondaal, S.F.V.; Schouten-van Meeteren, A.Y.N.; de Kruiff, C.C.; van Delden, J.J.M.; Kars, M.C. Anticipating the future of the child and family in pediatric palliative care: A qualitative study into the perspectives of parents and healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.H.; Jacobs, M.B.; October, T.W. Communication Skills and Practices Vary by Clinician Type. Hosp. Pediatr. 2020, 10, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birchley, G.; Thomas-Unsworth, S.; Mellor, C.; Baquedano, M.; Ingle, S.; Fraser, J. Factors affecting decision-making in children with complex care needs: A consensus approach to develop best practice in a UK children’s hospital. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2022, 6, e001589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Beaune, L.; Barrera, M.; Blumberg, J.; Belletrutti, M. Examining the Experiences of Fathers of Children with a Life-Limiting Illness. J. Soc. Work. End. Life Palliat. Care 2016, 12, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.J.; Bayliss, A.; Sozer, A.; Buchanan, F.; Breen-Reid, K.; De Castris-Garcia, K.; Green, M.; Quinlan, M.; Wong, N.; Frappier, S.; et al. Patient, Caregiver, and Clinician Participation in Prioritization of Research Questions in Pediatric Hospital Medicine. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e229085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, L.; Benzies, K.; Barnard, C.; Raffin Bouchal, S. Health Care Professionals’ Experiences of Providing Care to Hospitalized Medically Fragile Infants and Their Parents. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 53, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, C.; Sandhu, A.; Cooke, S. When Differing Perspectives between Health Care Providers and Parents Lead to “Communication Crises”: A Conceptual Framework to Support Prevention and Navigation in the Pediatric Hospital Setting. Hosp. Pediatr. 2019, 9, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigert, H.; Dellenmark, M.B.; Bry, K. Strengths and weaknesses of parent-staff communication in the NICU: A survey assessment. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennick, J.E.; St-Sauveur, I.; Knox, A.M.; Ruddy, M. Exploring the experiences of parent caregivers of children with chronic medical complexity during pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: An interpretive descriptive study. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrington, S.F.; Paquette, E.; Johnson, K.A. Cross-cultural Interactions and Shared Decision-making. Pediatrics 2018, 142, S187–S192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelson, K.N.; Charleston, E.; Aniciete, D.Y.; Sorce, L.R.; Fragen, P.; Persell, S.D.; Ciolino, J.D.; Clayman, M.L.; Rychlik, K.; Jones, V.A.; et al. Navigator-Based Intervention to Support Communication in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Crit. Care 2020, 29, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odeniyi, F.; Nathanson, P.G.; Schall, T.E.; Walter, J.K. Communication Challenges of Oncologists and Intensivists Caring for Pediatric Oncology Patients: A Qualitative Study. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhe, K.M.; Wangmo, T.; De Clercq, E.; Badarau, D.O.; Ansari, M.; Kühne, T.; Niggli, F.; Elger, B.S. Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group (SPOG) Putting patient participation into practice in pediatrics-results from a qualitative study in pediatric oncology. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, J.K.; Frydenberg, A.R.; Donath, S.K.; Marks, M.M. Simulated parents: Developing paediatric trainees’ skills in giving bad news. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2009, 45, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Friedman, S.H.; Collin, M.; Martin, R.J. Staff perceptions of challenging parent-staff interactions and beneficial strategies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limacher, R.; Fauchère, J.-C.; Gubler, D.; Hendriks, M.J. Uncertainty and probability in neonatal end-of-life decision-making: Analysing real-time conversations between healthcare professionals and families of critically ill newborns. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.; Spry, J.L.; Hill, E.; Coad, J.; Dale, J.; Plunkett, A. Parental experiences of end of life care decision-making for children with life-limiting conditions in the paediatric intensive care unit: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Myers, H.; Eng, D.; Kilshaw, L.; Abraham, J.; Buchanan, G.; Eggimann, L.; Kelly, M. Evaluation of the ‘Talking Together’ simulation communication training for ‘goals of patient care’ conversations: A mixed-methods study in five metropolitan public hospitals in Western Australia. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslakson, R.A.; Curtis, J.R.; Nelson, J.E. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 2418–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, R.; Paladino, J.; Neville, B.A.; Hutchings, M.; Kavanagh, J.; Geerse, O.P.; Lakin, J.; Sanders, J.J.; Miller, K.; Lipsitz, S.; et al. Effect of the Serious Illness Care Program in Outpatient Oncology: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seccareccia, D.; Wentlandt, K.; Kevork, N.; Workentin, K.; Blacker, S.; Gagliese, L.; Grossman, D.; Zimmermann, C. Communication and Quality of Care on Palliative Care Units: A Qualitative Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.; Smith, C.D.; Masoudi, F.A.; Blaum, C.S.; Dodson, J.A.; Green, A.R.; Kelley, A.; Matlock, D.; Ouellet, J.; Rich, M.W.; et al. Decision Making for Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions: Executive Summary for the American Geriatrics Society Guiding Principles on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisk, B.A. Improving communication in pediatric oncology: An interdisciplinary path forward. Cancer 2021, 127, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, M.M.; Windsor, C.; Chambers, S.; Green, T.L. A Scoping Review of End-of-Life Communication in International Palliative Care Guidelines for Acute Care Settings. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 425–437.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.J.; Curtis, J.R.; Tulsky, J.A. Achieving Goal-Concordant Care: A Conceptual Model and Approach to Measuring Serious Illness Communication and Its Impact. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, S17–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, E.; Reid, M.C.; Shengelia, R.; Adelman, R.D. Directly observed patient-physician discussions in palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review of the literature. J. Palliat. Med. 2010, 13, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quintero, X.; Claros-Hulbert, A.; Tello-Cajiao, M.E.; Bolaños-Lopez, J.E.; Cuervo-Suárez, M.I.; Durán, M.G.G.; Gómez-García, W.; McNeil, M.; Baker, J.N. Using EmPalPed—An Educational Toolkit on Essential Messages in Palliative Care and Pain Management in Children-As a Strategy to Promote Pediatric Palliative Care. Children 2022, 9, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scoy, L.J.; Reading, J.M.; Scott, A.M.; Chuang, C.; Levi, B.H.; Green, M.J. Exploring the Topics Discussed During a Conversation Card Game About Death and Dying: A Content Analysis. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2016, 52, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wreesmann, W.-J.W.; Lorié, E.S.; van Veenendaal, N.R.; van Kempen, A.A.M.W.; Ket, J.C.F.; Labrie, N.H.M. The functions of adequate communication in the neonatal care unit: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, N.H.M.; van Veenendaal, N.R.; Ludolph, R.A.; Ket, J.C.F.; van der Schoor, S.R.D.; van Kempen, A.A.M.W. Effects of parent-provider communication during infant hospitalization in the NICU on parents: A systematic review with meta-synthesis and narrative synthesis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1526–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.; Young, B. How could we know if communication skills training needed no more evaluation? The case for rigour in research design. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1401–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallman, M.L.; Bellury, L.M. Communication in Pediatric Critical Care Units: A Review of the Literature. Crit. Care Nurse 2020, 40, e1–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbaugh, B.L.; Tomlinson, P.S.; Kirschbaum, M. Parents’ perceptions of nurses’ caregiving behaviors in the pediatric intensive care unit. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2004, 27, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, C.; Drotar, D. Research on the quality of parent-provider communication in pediatric care: Implications and recommendations. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2003, 24, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, D.E.; Caceres-Serrano, A.; Radhakrishnan, V.; Salaverria, C.E.; Kambugu, J.B.; Sisk, B.A. A proposed global framework for pediatric cancer communication research. Cancer 2022, 128, 1888–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thodé, M.; Pasman, H.R.W.; van Vliet, L.M.; Damman, O.C.; Ket, J.C.F.; Francke, A.L.; Jongerden, I.P. Feasibility and effectiveness of tools that support communication and decision making in life-prolonging treatments for patients in hospital: A systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakonidou, S.; Kotzamanis, S.; Tallett, A.; Poots, A.J.; Modi, N.; Bell, D.; Gale, C. Parents’ Experiences of Communication in Neonatal Care (PEC): A neonatal survey refined for real-time parent feedback. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023, 108, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, D.; Young, J.; Watson, K.; Ware, R.S.; Pitcher, A.; Bundy, R.; Greathead, D. Effectiveness of a tool to improve role negotiation and communication between parents and nurses. Paediatr. Nurs. 2008, 20, 14–19. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18816909/ (accessed on 30 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mummah, S.A.; Robinson, T.N.; King, A.C.; Gardner, C.D.; Sutton, S. IDEAS (Integrate, Design, Assess, and Share): A Framework and Toolkit of Strategies for the Development of More Effective Digital Interventions to Change Health Behavior. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomborg, K.; Munch, L.; Krøner, F.H.; Elwyn, G. “Less is more”: A design thinking approach to the development of the agenda-setting conversation cards for people with type 2 diabetes. PEC Innov. 2022, 1, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northway, R.; Rees, S.; Davies, M.; Williams, S. Hospital passports, patient safety and person-centred care: A review of documents currently used for people with intellectual disabilities in the UK. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 5160–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patient passports aim to speed appropriate care for medically complex children presenting to ED. ED Manag. 2015, 27, 56–59.

- Leavey, G.; Curran, E.; Fullerton, D.; Todd, S.; McIlfatrick, S.; Coates, V.; Watson, M.; Abbott, A.; Corry, D. Patient and service-related barriers and facitators to the acceptance and use of interventions to promote communication in health and social care: A realist review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.W.; Irvine, F.E.; Jones, P.R.; Spencer, L.H.; Baker, C.R.; Williams, C. Language awareness in the bilingual healthcare setting: A national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.C.; Bouamrane, M.-M.; Dunlop, M. Design Requirements for a Digital Aid to Support Adults with Mild Learning Disabilities During Clinical Consultations: Qualitative Study with Experts. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 6, e10449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfi, K.; Rosenblum, S. Activity and participation characteristics of adults with learning disabilities—A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitras, M.-E.; Maltais, M.-E.; Bestard-Denommé, L.; Stewart, M.; Fortin, M. What are the effective elements in patient-centered and multimorbidity care? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.; Perry, R.; Blanchard, K.; Linsell, L. Effectiveness of a three-day communication skills course in changing nurses’ communication skills with cancer/palliative care patients: A randomised controlled trial. Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M. Parents’ and nurses’ attitudes to family-centred care: An Irish perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 2341–2348. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18036123/ (accessed on 30 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.; Hopkins, A.; Shilkofski, N.A.; Levine, R.B.; Hernandez, R.G. Difficult Patient Encounters: Assessing Pediatric Residents’ Communication Skills Training Needs. Cureus 2018, 10, e3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.B.; Macieira, T.G.R.; Garbutt, S.J.; Citty, S.W.; Stephen, A.; Ansell, M.; Glover, T.L.; Keenan, G. The Use of Simulation to Teach Nursing Students and Clinicians Palliative Care and End-of-Life Communication: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2018, 35, 1140–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marino, L.V.; Collaḉo, N.; Coyne, S.; Leppan, M.; Ridgeway, S.; Bharucha, T.; Cochrane, C.; Fandinga, C.; Palframan, K.; Rees, L.; et al. The Development of a Communication Tool to Aid Parent-Centered Communication between Parents and Healthcare Professionals: A Quality Improvement Project. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202706

Marino LV, Collaḉo N, Coyne S, Leppan M, Ridgeway S, Bharucha T, Cochrane C, Fandinga C, Palframan K, Rees L, et al. The Development of a Communication Tool to Aid Parent-Centered Communication between Parents and Healthcare Professionals: A Quality Improvement Project. Healthcare. 2023; 11(20):2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202706

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarino, Luise V., Nicole Collaḉo, Sophie Coyne, Megan Leppan, Steve Ridgeway, Tara Bharucha, Colette Cochrane, Catarina Fandinga, Karla Palframan, Leanne Rees, and et al. 2023. "The Development of a Communication Tool to Aid Parent-Centered Communication between Parents and Healthcare Professionals: A Quality Improvement Project" Healthcare 11, no. 20: 2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202706

APA StyleMarino, L. V., Collaḉo, N., Coyne, S., Leppan, M., Ridgeway, S., Bharucha, T., Cochrane, C., Fandinga, C., Palframan, K., Rees, L., Osman, A., Johnson, M. J., Hurley-Wallace, A., & Darlington, A.-S. E. (2023). The Development of a Communication Tool to Aid Parent-Centered Communication between Parents and Healthcare Professionals: A Quality Improvement Project. Healthcare, 11(20), 2706. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202706