Management of Diabetes during School Hours: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Denmark

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

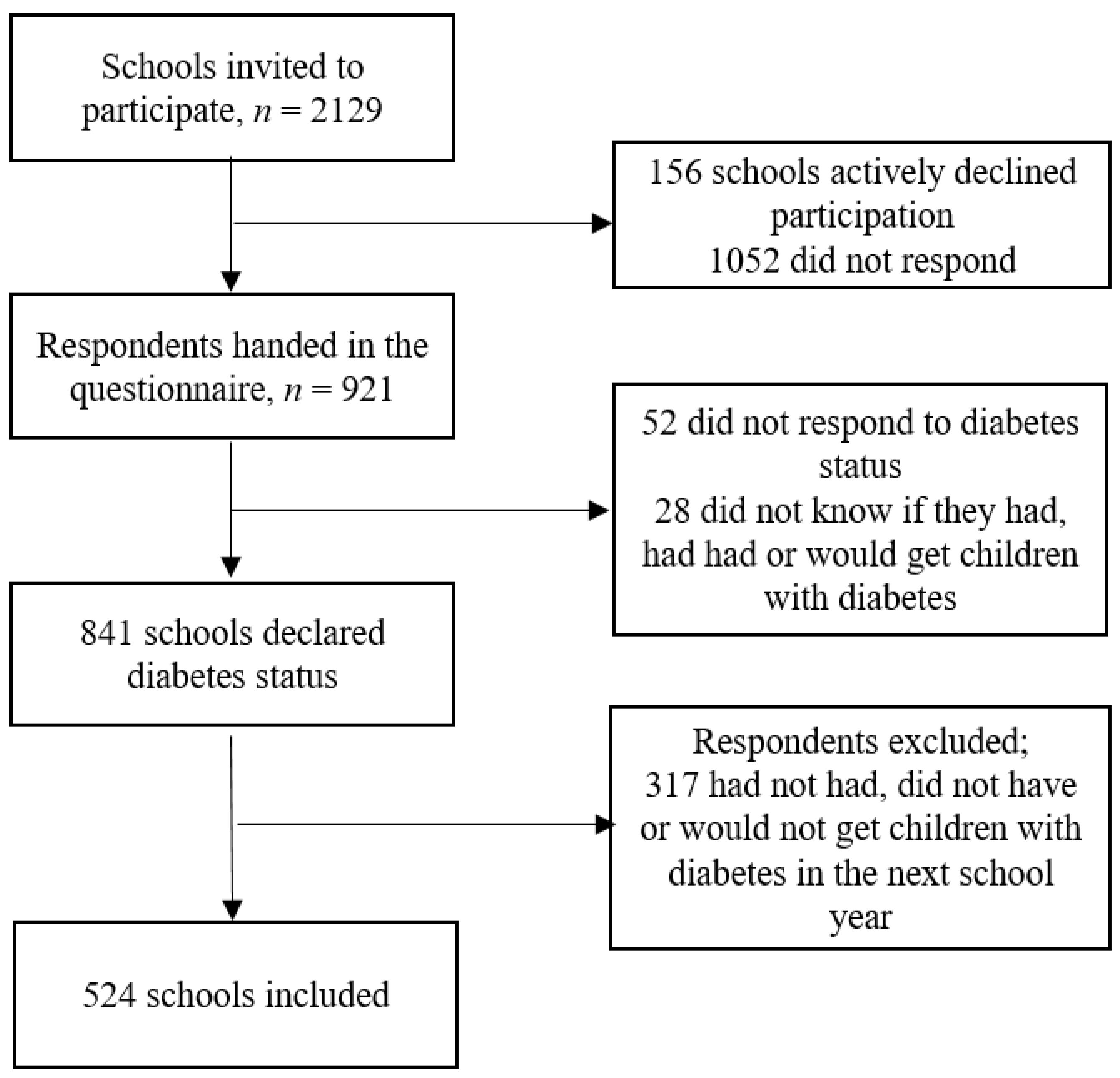

2.1. Design and Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Development of the Questionnaire

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Law and Equal Opportunity

3.2. Individualized Diabetes Plan

3.3. Education and Knowledge

3.4. Food (Access)

3.5. Physical Activity

3.6. Self-Management

3.7. School/Home Cooperation

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Perspectives to Future Work in the Field

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Domain: Law and Equal Opportunity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISPAD Guidelines | KIDS Questionnaire Items | Questionnaire Response Categories | Criteria for Satisfactory Response | Proportion of Schools with Satisfactory Response |

| Does the school have a guideline/policy for handling chronic illness among students? |

| Yes | 21.7% |

| Does the school have a guideline/policy for handling diabetes among students? |

| Yes | 25.9% | |

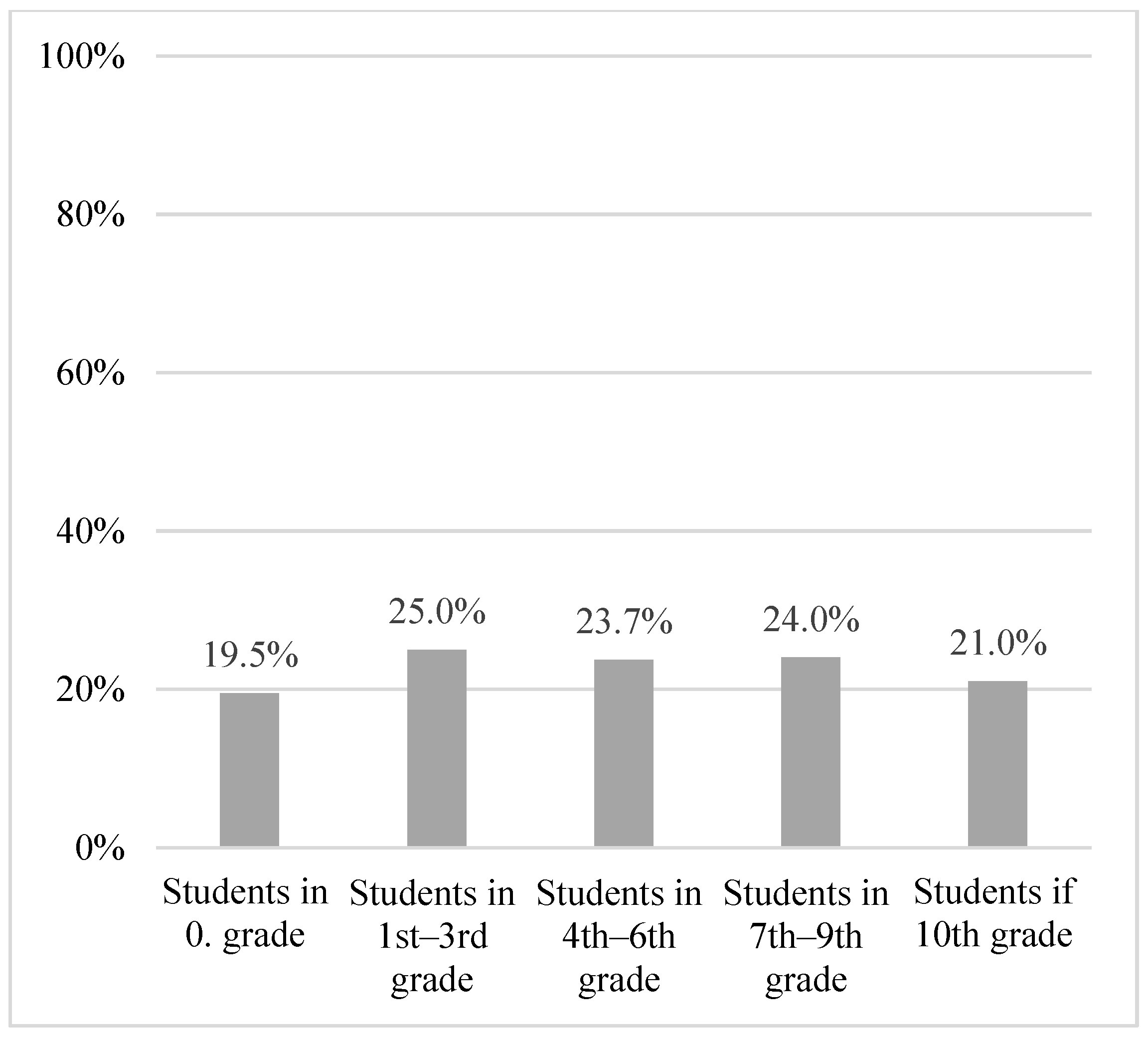

| Does the school allocate extra hours to students with diabetes? State approximate amount of time for each age group: 1. Students in 0th grade 2. Students in 1st–3rd grade 3. Students in 4th–6th grade 4. Students in 7th–9th grade 5. Students in 10th grade | Text box | >1 h | 1. 19.5% 2. 25% 3. 23.7% 4. 24% 5. 21% | |

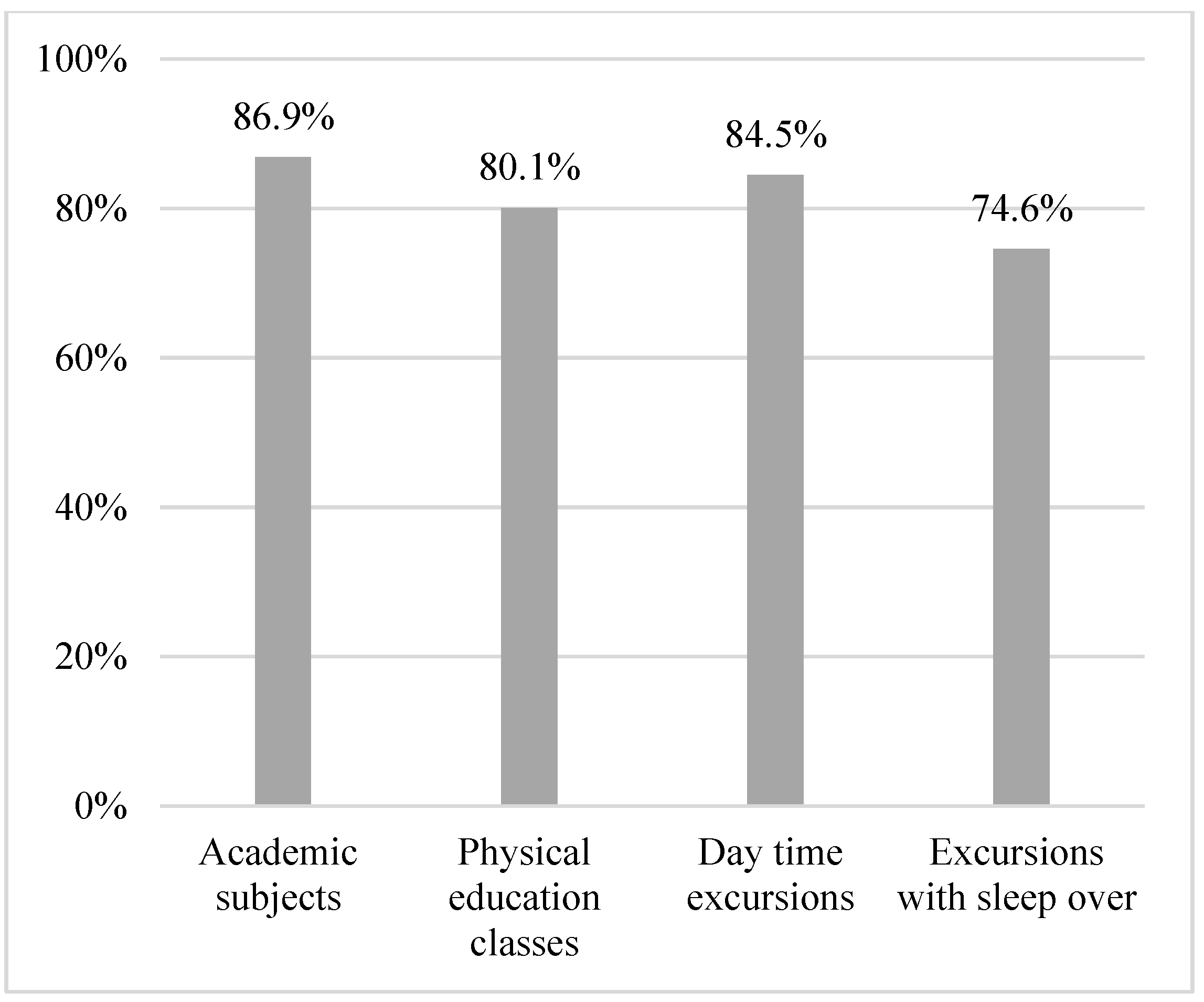

| On a scale from 1 to 5 (5 being the highest), to what extent do you experience being able to include students with diabetes in a school day on equal terms with students without diabetes during…. 1. Academic subjects 2. Physical education classes 3. Day time excursions 4. Overnight excursions | Likert scale: 1–5 | For all: 4–5 | 1. 86.9% 2. 80.1% 3. 84.5% 4. 74.6% | |

| Domain: Individualized diabetes plan | ||||

| ISPAD guidelines | KIDS questionnaire items | Questionnaire response categories | Criteria for satisfactory response | Proportion of schools with satisfactory response |

| Does the school have an action plan, in case a students with diabetes experiences low blood sugar/insulin chock (hypoglycemic reaction)? |

| Yes | 61.7% |

| Does the school have one or more persons able to help students with diabetes administer insulin/adjust insulin pump if necessary? |

| Yes | 78.5% | |

| Domain: Education and knowledge | ||||

| ISPAD guidelines | KIDS questionnaire items | Questionnaire response categories | Criteria for satisfactory response | Proportion of schools with satisfactory response |

| Did teachers and other personnel receive teaching regarding supporting students with diabetes? |

| Yes | 77.2% |

| What do you think is the biggest challenge for the school, in regards to management and support to students with diabetes? |

| It is not considered a challenge to have students with diabetes at the school | 54.3% | |

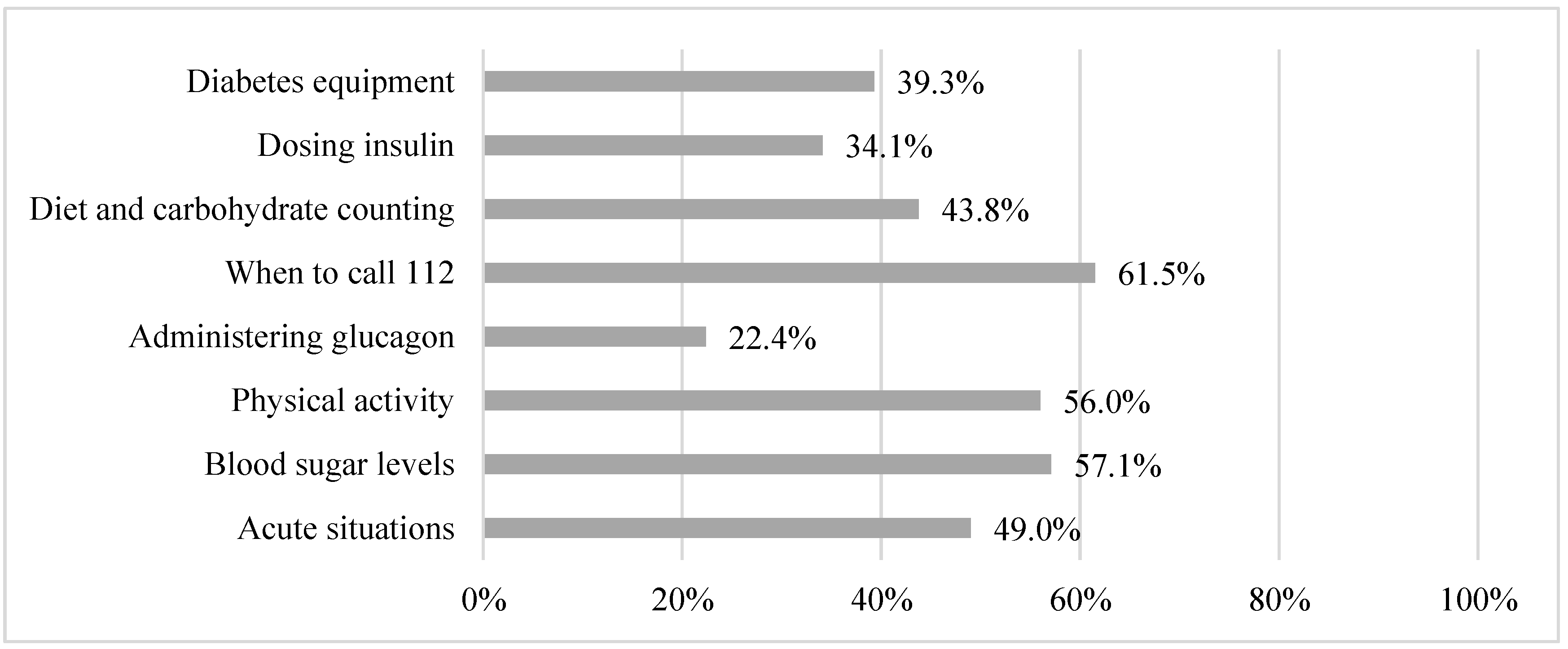

| On a scale from 1–5 (5 being the highest), to what extent do you feel like you have adequate knowledge about…. 1. Acute situations 2. Blood sugar levels 3. Physical activity 4. Administering glucagon 5. When to call 112 6. Diet and carbohydrate counting 7. Dosing insulin 8. The students diabetes equipment | Likert scale: 1–5 | For all: 4–5 | 1. 49.0% 2. 57.1% 3. 56.0% 4. 22.4% 5. 61.5% 6. 43.8% 7. 34.1% 8. 39.3% | |

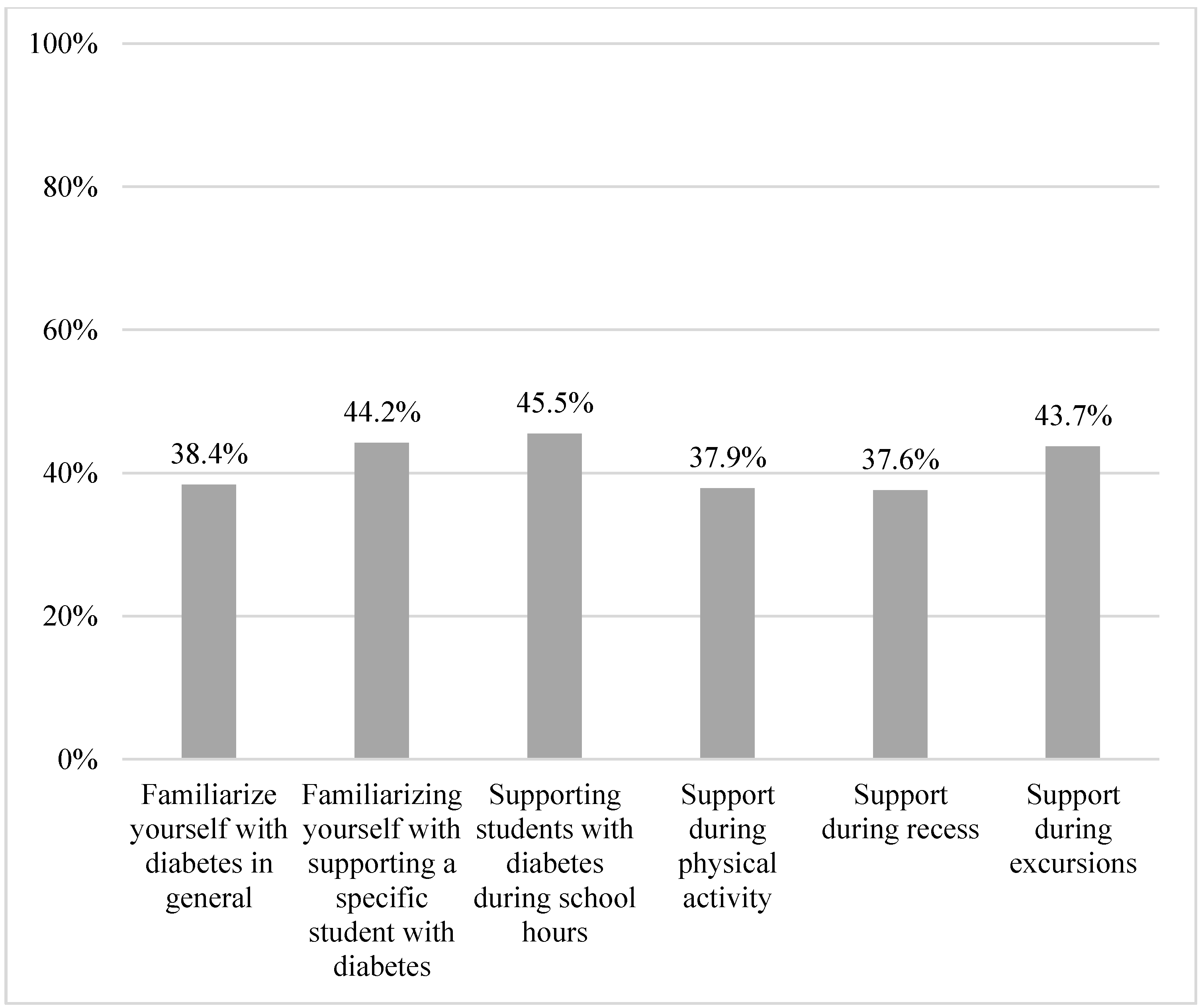

| On a scale from 1–5 (5 being the highest), to what extent do you feel you have adequate time to… 1. Familiarize yourself with diabetes in general 2. Familiarizing yourself with supporting a specific student with diabetes 3. Supporting students with diabetes during school hours 4. Support during physical activity 5. Support during recess 6. Support during excursions | Likert scale: 1–5 | For all: 4–5 | 1. 38.4% 2. 44.2% 3. 45.5% 4. 37.9% 5. 37.6% 6. 43.7% | |

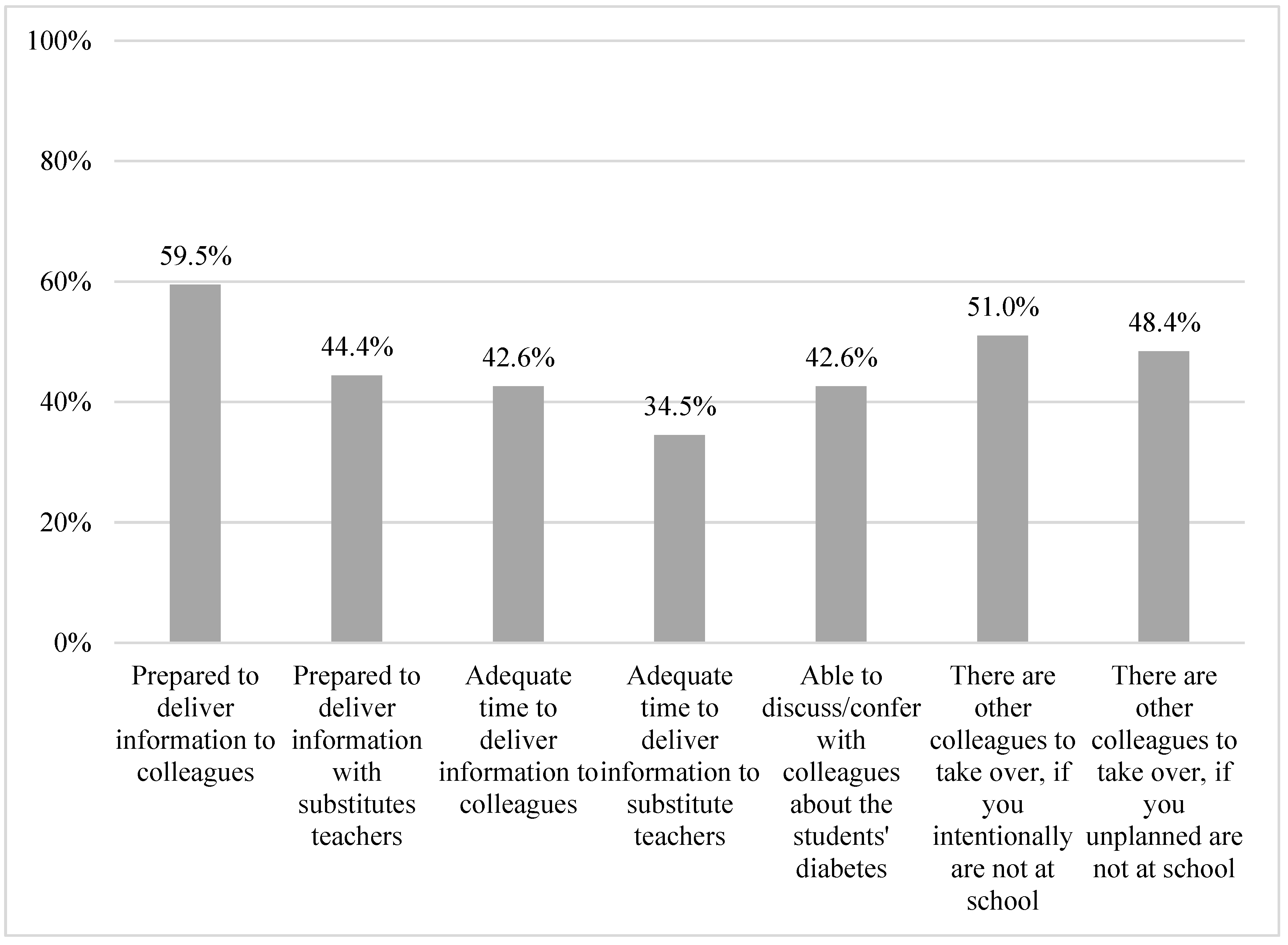

| On a scale from 1–5 (5 being the highest), to what extent do you experience… 1. Being well prepared to deliver information to colleagues 2. Being well prepared to deliver information to substitutes teachers 3. You have adequate time to deliver information to colleagues 4. You have adequate time to deliver information to substitute teachers 5. You are able to discuss/confer with colleagues about the students’ diabetes 6. There are other colleagues to take over, if you intentionally are not at school 7. There are other colleagues to take over, if you unplanned are not at school | Likert scale: 1–5 | For all: 4–5 | 1. 59.5% 2. 44.4% 3. 42.6% 4. 34.5% 5. 42.6% 6. 51.0% 7. 48.4% | |

| On a scale from 1–5 (5 being the highest), to what extent do you feel you are prepared to… 1. Help the student with counting carbohydrates 2. Help the student with dosing insulin 3. Help the student during high blood sugar 4. Help the student during low blood sugar 5. Help the student during insulin chock/hypoglycemic reaction 6. Help the student dosing insulin during activities | Likert scale: 1–5 | For all 4–5 | 1. 38.9% 2. 39.1% 3. 52.1% 4. 60.3% 5. 35.2% 6. 36.3% | |

| Domain: Food (Access) | ||||

| ISPAD guidelines | KIDS questionnaire items | Questionnaire response categories | Criteria for satisfactory response | Proportion of schools with satisfactory response |

| Are there any rules for where and when students with diabetes are allowed to eat/drink? |

| No, we do not have any rules | 72.9% |

| Domain: Psychical activity | ||||

| ISPAD guidelines | KIDS questionnaire items | Responsecategories in the questionnaire | Criteria for satisfactory response | Proportion of schools with satisfactory response |

| Are there activities at school where students with diabetes are limited/restricted? |

| No, there are no limitations/restrictions | 95.3% |

| It is possible for the school to have extra personnel on hand in some situations, for example excursions? |

Feel free to elaborate:_______ | Yes | 69.7% | |

| Domain: Self-management | ||||

| ISPAD guidelines | KIDS questionnaire items | Questionnaire response categories | Criteria for satisfactory response | Proportion of schools with satisfactory response |

| Are the students able to measure blood sugar levels at the school? |

| Yes | 97.4% |

| Are there any rules for where and when students with diabetes are allowed to use their phones? |

| No, they are allowed to use their phones in class and recess | 53.0% | |

| Are there any rules for when and where students with diabetes are allowed to use the restroom? |

| No | 96.2% | |

| Are students able to manage their diabetes, for example eat/drink, measure blood sugar without losing considerable time; 1.During class? 2. During recess? |

| Yes | 1. 85.7% 2. 84.9% | |

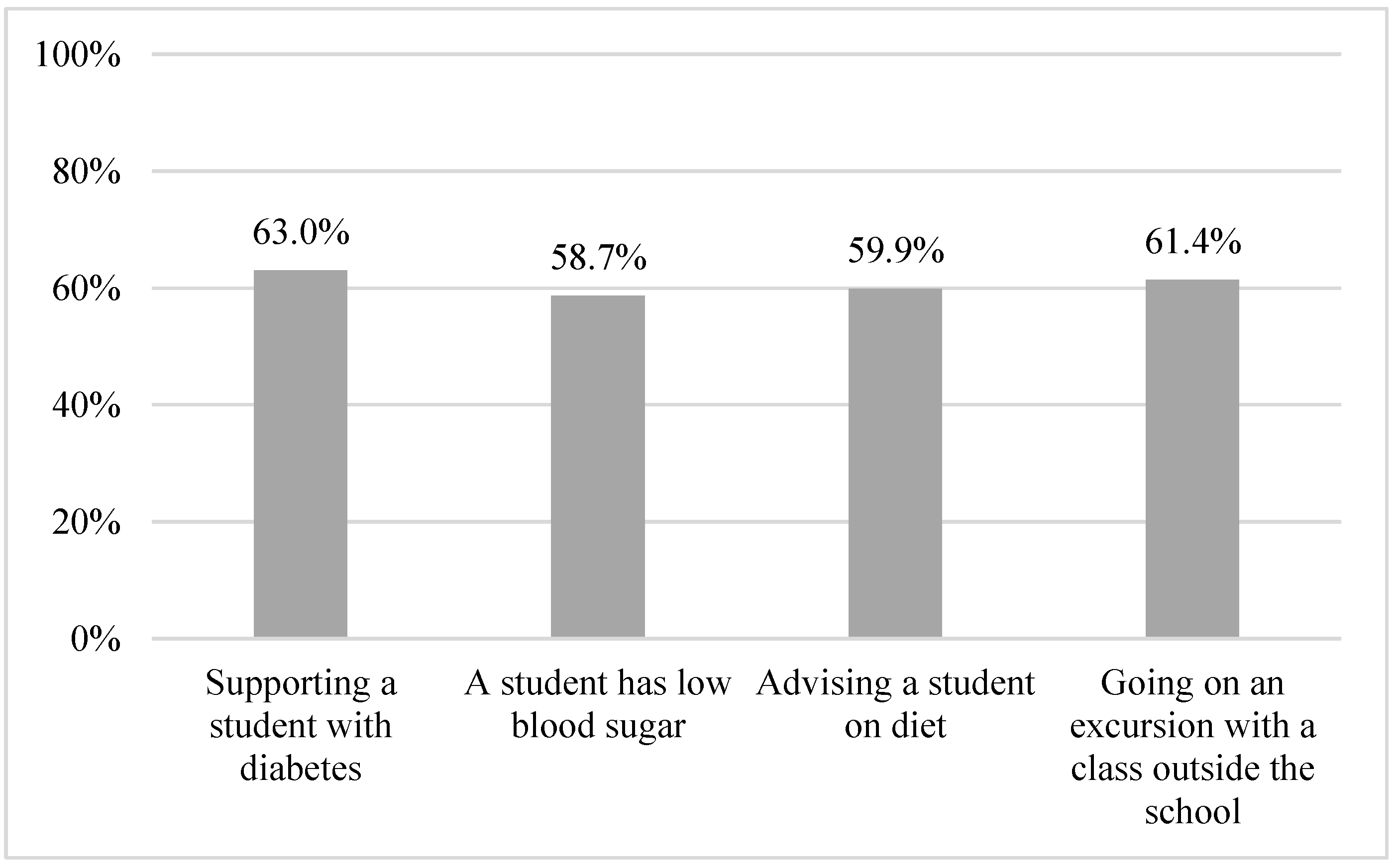

| On a scale from 1–5 (5 being the highest), to what extent do you feel unsafe if… 1. You have to support a student with diabetes 2. A student has low blood sugar 3. You have to advise a student on diet 4. You have to go on an excursion with a class outside the school, where there is a student with diabetes | Likert scale: 1–5 | For all: 1–2 | 1. 63.0% 2. 58.7% 3. 59.9% 4. 61.4% | |

| Domain: School/home cooperation | ||||

| ISPAD guidelines | KIDS questionnaire items | Questionnaire response categories | Criteria for satisfactory response | Proportion of schools with satisfactory response |

| How is information from the parents delivered? |

| In a meeting between parents and school | 37.4% |

| Do parents of students with diabetes hand out; 1. Relevant information about management of diabetes? 2. The necessary supplies (glucagon, strips for blood glucose measurements, snacks, juice/dextrose? |

| Yes | 1. 81.4% 2. 84.6% | |

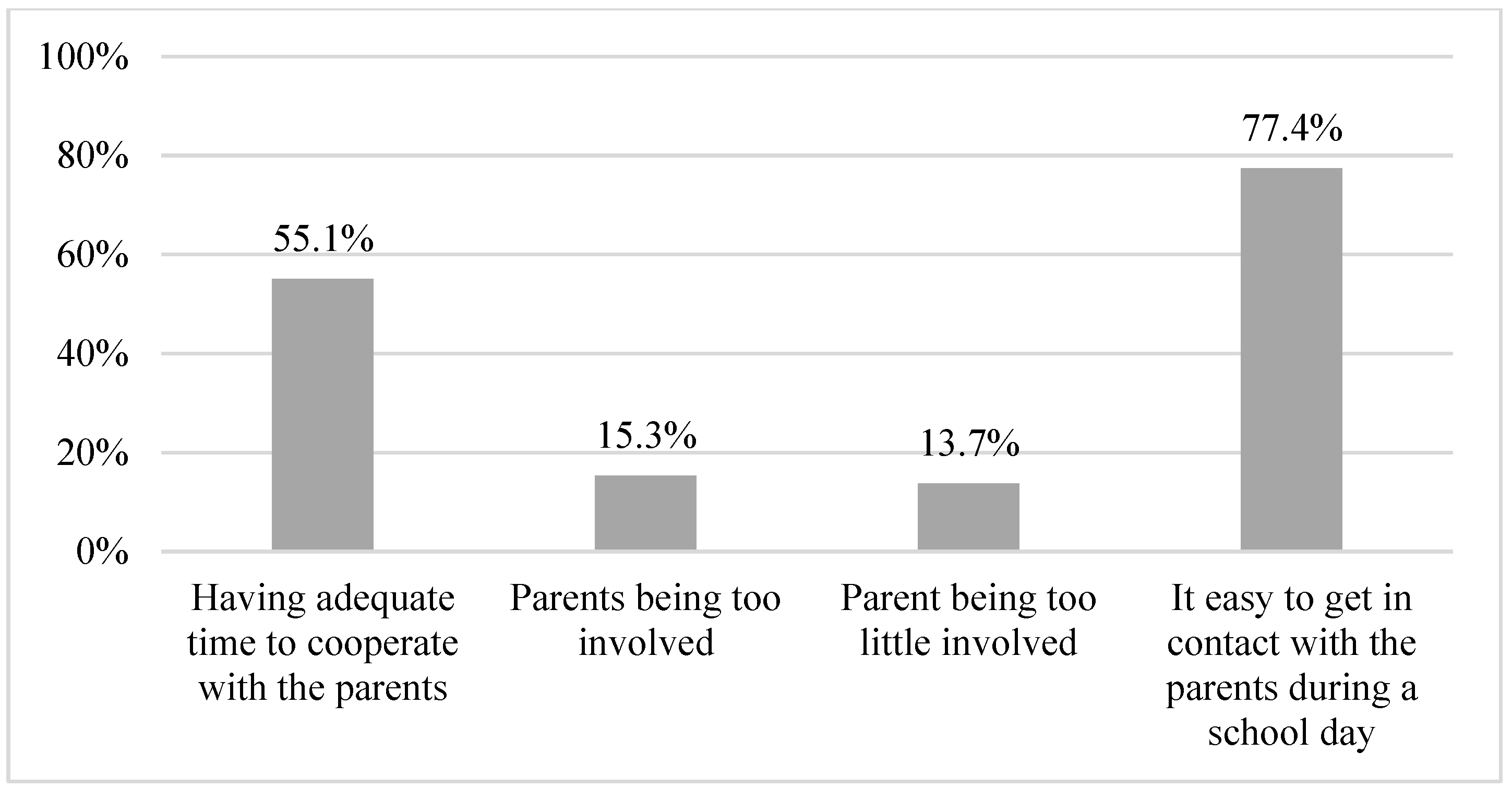

| On a scale from 1–5 (5 being the highest), to what extent do you experience … 1. Having adequate time to cooperate with the parents 2. Parents being too involved 3. Parent being too little involved 4. It easy to get in contact with the parents during a school day | Likert scale: 1–5 | For all: 4–5 | 1. 55.1% 2. 15.3% 3. 13.7% 4. 77.4% | |

| Domain: Psychosocial environment | ||||

| ISPAD guidelines | KIDS questionnaire items | Questionnaire response categories | Criteria for satisfactory response | Proportion of schools with satisfactory response |

| ||||

References

- The International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; The International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://idf.org/aboutdiabetes/what-is-diabetes/facts-figures.html)%20placing (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Commissariat, P.V.; Harrington, K.R.; Bs, A.L.W.; Miller, K.M.; Hilliard, M.E.; Van Name, M.; DeSalvo, D.J.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Anderson, B.J.; DiMeglio, L.A.; et al. “I’m essentially his pancreas”: Parent perceptions of diabetes burden and opportunities to reduce burden in the care of children <8 years old with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 21, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iturralde, E.; Rausch, J.R.; Weissberg-Benchell, J.; Hood, K.K. Diabetes-Related Emotional Distress over Time. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingod, N.; Grabowski, D. In a vigilant state of chronic disruption: How parents with a young child with type 1 diabetes negotiate events and moments of uncertainty. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 42, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, Z.Q.; Koh, S.S.L.; Lim, P.K.; Lim, J.S.T.; Tam, W.; Shorey, S. Diabetes-Related Emotional Distress among Children/Adolescents and Their Parents: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Children and Education. Executive Order on Danish Primary School; Ministry of Children and Education: København, Denmark, 2022; § 14b, Section 1. [Google Scholar]

- Junco, L.A.; Fernández-Hawrylak, M. Teachers and Parents’ Perceptions of Care for Students with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Their Needs in the School Setting. Children 2022, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Särnblad, S.; Berg, L.; Detlofsson, I.; Jönsson, A.; Forsander, G. Diabetes management in Swedish schools: A national survey of attitudes of parents, children, and diabetes teams. Pediatr. Diabetes 2014, 15, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989; General assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Ministry of Children and Education. Executive Order on Danish Primary School; Ministry of Children and Education: København, Denmark, 2022; § 3a. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Children and Education. Executive Order on Danish Primary School; Ministry of Children and Education: København, Denmark, 2022; §5, section 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bratina, N.; Forsander, G.; Annan, F.; Wysocki, T.; Pierce, J.; Calliari, L.E.; Pacaud, D.; Adolfsson, P.; Dovč, K.; Middlehurst, A.; et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Management and support of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes in school. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codner, E.; Acerini, C.L.; Craig, M.E.; Hofer, S.E.; Maahs, D.M. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: What is new in diabetes care? Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denmark Statistics. Inventory of Primary Schools in Denmark 2021; Denmark Statistics. Available online: https://www.uvm.dk/statistik/grundskolen/personale-og-skoler/antal-grundskoler (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Lewis, D.W.; Powers, P.A.; Goodenough, M.F.; Poth, M.A. Inadequacy of In-School Support for Diabetic Children. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2003, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denmark Statistics. Municipality Groups v1:2018–2022; Denmark Statistics. Available online: https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/dokumentation/nomenklaturer/kommunegrupper (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Gutzweiler, R.F.; Neese, M.; In-Albon, T. Teachers’ Perspectives on Children with Type 1 Diabetes in German Kindergartens and Schools. Diabetes Spectr. 2020, 33, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Särnblad, S.; Åkesson, K.; Rn, L.F.; Rn, R.I.; Forsander, G. Improved diabetes management in Swedish schools: Results from two national surveys. Pediatr. Diabetes 2017, 18, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslund-Thomsen, H.; Hasselbalch, L.A.; Laugesen, B. Parental Experiences of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Danish Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 53, e149–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Manzanedo, J.V.; Laureano, F.C.-S.; Moreno-Vides, P.; de Castro-Maqueda, G.; Fernández-Santosa, J.R.; Ponce-González, J.G. Teachers’ knowledge about type 1 diabetes in south of Spain public schools. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 143, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bast, L.S.; Andersen, H.B.; Andersen, A.; Lauemøller, S.G.; Bonnesen, C.T.; Krølner, R.F. School Coordinators’ Perceptions of Organizational Readiness Is Associated with Implementation Fidelity in a Smoking Prevention Program: Findings from the X:IT II Study. Prev. Sci. 2021, 22, 312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnesen, C.T.; Toftager, M.; Madsen, K.R.; Wehner, S.K.; Jensen, M.P.; Rosing, J.A.; Laursen, B.; Rod, N.H.; Due, P.; Krølner, R.F. Study protocol of the Healthy High School study: A school-based intervention to improve well-being among high school students in Denmark. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Capital Region of Denmark | Central Denmark Region | North Denmark Region | Region Zealand | Region of Southern Denmark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, % (n) | 19% (101) | 29% (150) | 13% (66) | 12% (65) | 27% (142) |

| Institution, % (n) | |||||

| Primary school (public) | 63% (64) | 67% (100) | 65% (43) | 58% (38) | 49% (69) |

| Primary school (private) | 34% (34) | 19% (29) | 24% (16) | 35% (23) | 35% (49) |

| Boarding school | n ≤ 5 | 13% (19) | 11% (7) | n ≤ 5 | 15% (21) |

| Day school | n ≤ 5 | n ≤ 5 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | n ≤ 5 |

| Number of students per school, % (n) | |||||

| <199 students | 15% (15) | 31% (46) | 45% (28) | 31% (20) | 34% (48) |

| 200–399 students | 19% (19) | 23% (35) | 26% (17) | 31% (20) | 31% (44) |

| 400–599 students | 21% (21) | 21% (21) | 18% (27) | 25% (16) | 19% (27) |

| 600–799 students | 24% (24) | 19% (29) | 11% (7) | 12% (8) | 11% (16) |

| 800–999 students | 13% (13) | 7% (10) | n ≤ 5 | n ≤ 5 | n ≤ 5 |

| >1000 students | 9% (9) | n ≤ 5 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | n ≤ 5 |

| Respondents’ occupation, % (n) | |||||

| Administrative personnel | 14% (14) | 15% (23) | n ≤ 5 | 15% (10) | 12% (17) |

| Teacher | 14% (14) | 19% (29) | 17% (11) | 14% (9) | 27% (38) |

| Social worker | 7% (7) | 6% (9) | 9% (6) | 8% (5) | 6% (8) |

| Principal | 53% (53) | 49% (74) | 67% (44) | 45% (29) | 46% (65) |

| Other manager than principal | 11% (11) | 5% (7) | n ≤ 5 | 8% (5) | 7% (10) |

| Other, non-manager | n ≤ 5 | 5% (8) | 0% (0) | 11% (7) | n ≤ 5 |

| Area (wealth), % (n) | |||||

| Not so wealthy | 13% (13) | 16% (23) | 35% (23) | 24% (15) | 19% (26) |

| Very wealthy | 8% (8) | 3% (5) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | n ≤ 5 |

| Some wealth | 33% (33) | 17% (25) | 11% (7) | 19% (12) | 18% (25) |

| Not at all wealthy | n ≤ 5 | 4% (6) | 9% (6) | n ≤ 5 | 5% (7) |

| Average | 44% (44) | 60% (89) | 45% (30) | 51% (32) | 57% (80) |

| Non-Respondents | Respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 1052 (66.8%) | 524 (33.2%) |

| Region, n (%) | ||

| Capital Region of Denmark | 275 (26.1%) | 101 (19.3%) |

| Central Denmark Region | 184 (17.5%) | 150 (28.6%) |

| North Denmark Region | 103 (9.8%) | 66 (12.6%) |

| Region Zealand | 213 (20.2%) | 65 (12.4%) |

| Region of Southern Denmark | 277 (26.3%) | 142 (27.1%) |

| Municipalities, n (%) | ||

| Capital municipalities | 216 (20.5%) | 99 (18.9%) |

| Metropolitan Municipalities | 51 (4.8%) | 46 (8.8%) |

| Provincial municipalities | 238 (22.6%) | 95 (18.1%) |

| Commuter Municipalities | 227 (21.6%) | 112 (21.4%) |

| Rural Municipalities | 320 (30.4%) | 172 (32.8%) |

| Institution, n (%) | ||

| Boarding school, live in | 95 (9.0%) | 53 (10.1%) |

| Primary schools | 673 (64.0%) | 314 (59.9%) |

| Private primary school | 225 (21.4%) | 151 (28.8%) |

| Boarding schools | 59 (5.6%) | 6 (1.1%) |

| Proportion of Satisfactory Response | |

|---|---|

| Does the school have a guideline/policy for handling chronic illness among students? | 21.7% |

| Does the school have a guideline/policy for handling diabetes among students? | 25.9% |

| Does the school have an action plan, in case a students with diabetes experiences low blood sugar/insulin chock (hypoglycemic reaction)? | 61.7% |

| Does the school have one or more persons able to help students with diabetes administer insulin/adjust insulin pump if necessary? | 78.5% |

| Did teachers and other personnel receive teaching regarding supporting students with diabetes? | 77.2% |

| What do you think is the biggest challenge for the school, in regards to management and support to students with diabetes? | 54.3% |

| Are there any rules for where and when students with diabetes are allowed to eat/drink? | 72.9% |

| Are there activities at school where students with diabetes are limited/restricted? | 95.3% |

| It is possible for the school to have extra personnel on hand in some situations, for example excursions? | 69.7% |

| Are the students able to measure blood sugar levels at the school? | 97.4% |

| Are there any rules for where and when students with diabetes are allowed to use their phones? | 53.0% |

| Are there any rules for when and where students with diabetes are allowed to use the restroom? | 96.2% |

| Are students able to manage their diabetes, for example eat/drink, measure blood sugar without losing considerable time during class? | 85.7% |

| Are students able to manage their diabetes, for example eat/drink, measure blood sugar without losing considerable time during recess? | 84.9% |

| How is information from the parents delivered? | 37.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nannsen, A.Ø.; Kristensen, K.; Johansen, L.B.; Iken, M.K.; Madsen, M.; Pilgaard, K.A.; Grabowski, D.; Hangaard, S.; Schou, A.J.; Andersen, A. Management of Diabetes during School Hours: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Denmark. Healthcare 2023, 11, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020251

Nannsen AØ, Kristensen K, Johansen LB, Iken MK, Madsen M, Pilgaard KA, Grabowski D, Hangaard S, Schou AJ, Andersen A. Management of Diabetes during School Hours: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Denmark. Healthcare. 2023; 11(2):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020251

Chicago/Turabian StyleNannsen, Anne Østergaard, Kurt Kristensen, Lise Bro Johansen, Mia Kastrup Iken, Mette Madsen, Kasper Ascanius Pilgaard, Dan Grabowski, Stine Hangaard, Anders Jørgen Schou, and Anette Andersen. 2023. "Management of Diabetes during School Hours: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Denmark" Healthcare 11, no. 2: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020251

APA StyleNannsen, A. Ø., Kristensen, K., Johansen, L. B., Iken, M. K., Madsen, M., Pilgaard, K. A., Grabowski, D., Hangaard, S., Schou, A. J., & Andersen, A. (2023). Management of Diabetes during School Hours: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study in Denmark. Healthcare, 11(2), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020251