Personalized Technological Support for Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Co-Design Approach Involving Potential End Users and Healthcare Professionals in Three Focus Groups in Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. The DemiCare Project

1.2.1. Study Group and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

1.2.2. Aim and Features of the Project

1.2.3. Main Outcome: Personalized Support for ICs

1.2.4. Overall Novelty of DemiCare

1.3. Aim of the Study and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Co-Design Phase

2.1.1. Co-Creation and Focus Groups

2.1.2. Recruitment of Participants

2.1.3. Data Collection

2.2. Ethical Issues

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of EUs

3.2. Characteristics of HPs

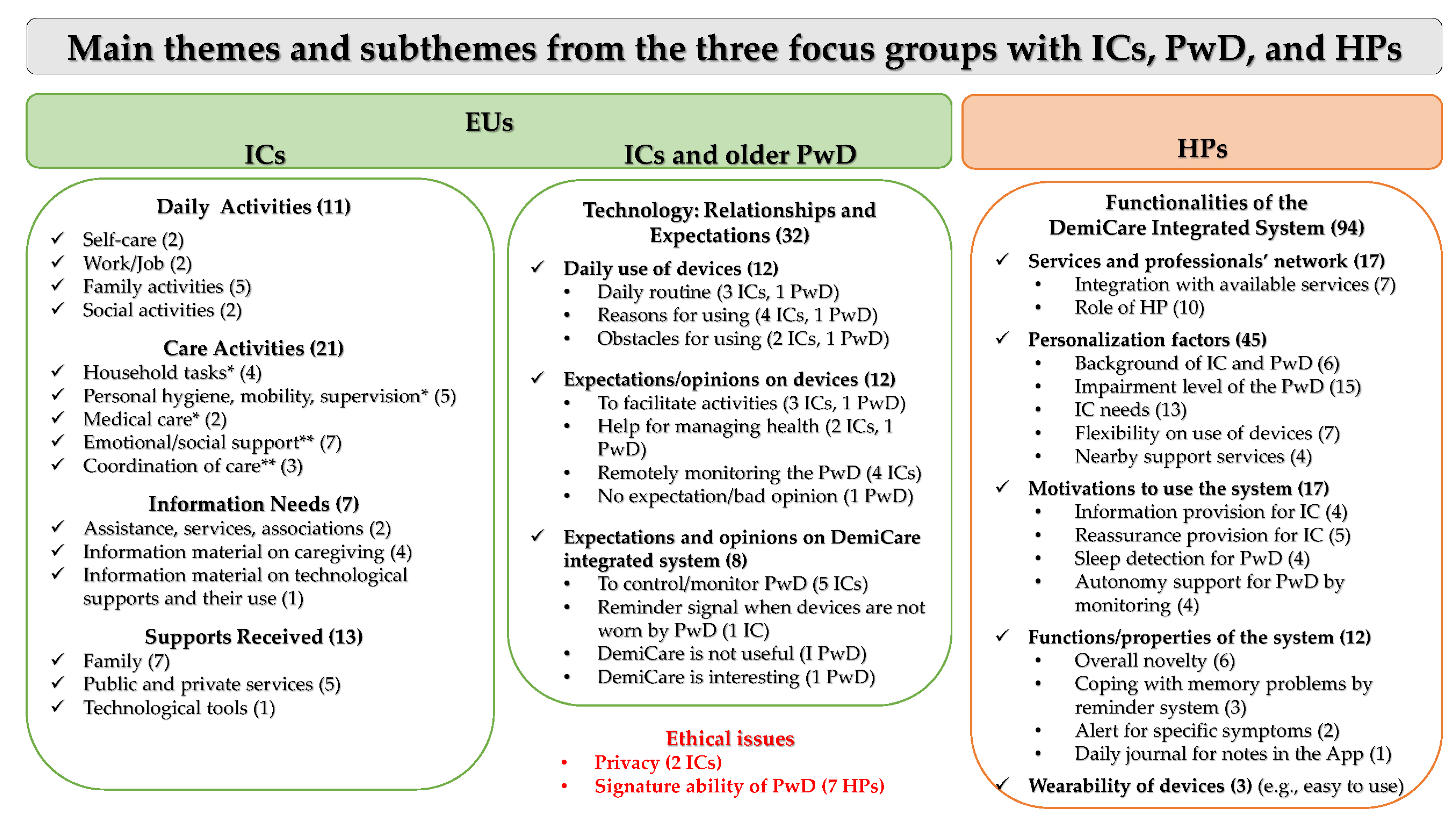

3.3. Main Themes and Subthemes

3.4. Focus Group with ICs

“I have really very little time for myself!”(IC-1)

“I am the main support for accompanying her [mother] to the various medical examinations [...] and for managing the bureaucratic procedures.”(IC-2)

“My mother does not feel comfortable with another person [son] with regard to her personal hygiene.”(IC-1)

“It would be important to know the opportunities to get support and assistance, perhaps from public entities.”(IC-1)

“It would be useful to have information to find an adequate private assistant with expertise in the care of older persons with dementia.”(IC-2)

“Information on the use of technology in these circumstances could be really helpful.”(IC-2)

“I have no other people around who can help me, just family members, but I am the primary assistant. […] Then, there is the support of the daycare center.”(IC-1)

“Occasionally my children support me to accompany my mother to the daycare center.”(IC-2)

“We have installed a video camera for better monitoring her [mother] and to talk with her. […] However, I do not feel I am skilled enough as regards the overall technology!”(IC-1)

3.5. Focus Group with ICs and Older PwD

“I use the tablet and the smartphone regularly, both at home and outside. I search for various sources of information on the internet.”(IC-2)

“I use a PC with my wife, and the smartphone alone.”(PwD-3)

“Currently, the smartphone can do many things; it supports people in many tasks.”(PwD-3)

“It is not always easy to use technology! […] I use an old basic phone with two buttons, one green to open the calls, one red to close them. I feel I do not need anything else!”(PwD-2)

“Smart devices can facilitate certain daily activities and can also be used for leisure.”(IC-3)

“Technology could be useful to monitor PwD when they are not close to their family, and the digital device can send an alert in case of falls.”(IC-2)

“Older people need to use simple things!”(PwD-2)

“Smart soles with GPS are useful when older people are outside their homes to alert their family for some urgent needs. […] The smartwatch is useful also during the night to continuously monitor blood pressure.”(IC-3)

“Smart soles could beep in case they have not been worn for a long time, but this beep should not be continuous and annoying.”(IC-2)

“I have never forgotten anything! My old watch is enough! I do not need any smartwatch, just a normal watch is enough. It’s easier.”(PwD-2)

“I would try the DemiCare system. I would also like to know how many countries work in the study and if there are companies producing smart devices in the consortium.”(PwD-3)

“Smart devices can be of great help, but privacy must be protected.”(IC-3)

3.6. Focus Group with HPs

“There is a need for integration with existing services, in order to create a network.”(HP-1)

“The app works well in association with a professional filter that supports ICs to deal with the situation. I do not think all ICs can fully understand the patient’s behavior and react. […] So, the app is a tool, a support, but it is not adequate by itself.”(HP-6)

“I think that personalization of digital devices is a very important aspect, since there are different needs.”(HP-3)

“In the case of MCI, some tools are needed; in the case of MD, other tools could be necessary.”(HP-2)

“Information provided by the app, such as actions for managing symptoms and behaviors, could be interpreted differently by ICs, depending on their preparation, according to their character, because the anxious state of a caregiver has an impact on this.”(HP-4)

“The knowledge that family members have about dementia and its consequences, how it will evolve, is heterogeneous, and the app should start from this consideration.”(HP-6)

“For PwD it is not easy to wear prostheses, hearing aids, glasses, and so on. Thus, they should be free to use the devices and to decide when/how long to use them during the day.”(HP-7)

“Flexibility should be precisely this: caregivers working in the afternoon can watch the app in the morning; caregivers working in the morning can watch it in the evening. People are different: someone could watch the app five times a day; someone else, only once a week.”(HP-4)

“This app should be a compass that orients people toward existing/nearby support services. A geolocation system would be useful to know what services and possibilities there are in the area where people live, especially in the municipality and in the neighborhood.”(HP-2)

“The information provided by the app is good and validated, and this can convince ICs to use it instead of generally navigating the internet. Information from the internet is not always correct and is not always interpreted in the best way.”(HP-1)

“The app can be reassuring, especially when ICs need to manage problematic behaviors and when they live far away from PwD. […] So, the information available from the app could support the IC to calm down the person being cared for, somehow.”(HP-7)

“The DemiCare system could help to maintain the autonomy of seniors who still live alone for as long as possible, and this is no small thing.”(HP-5)

“It is important to know what happens during the night because sleep disorders indicate the existence of problems during the day. […] To know this also helps HPs from pharmacological and overall care management points of view.”(HP-2)

“The system could remind PwD to do the activities of daily living, thus solving a practical problem.”(HP-2)

“It could be useful to put in the app a section reserved for the IC, a virtual diary for writing care problems that might have arisen during the daily routine and to write how the IC solved them.”(HP-3)

“The comfort of a device is important; it should be light, easy to use, and charged […]. Moreover, the wearability of a smartwatch could be perceived as greater when PwD already wear a watch daily as something they have always done.”(HP-5)

“Personal and sensitive data are required in this study, so clear informed consent must be given, particularly in the case of a person with a diagnosis of dementia.”(HP-1)

“Often, an older patient with MCI is not willing to be controlled or controllable.”(HP-4)

4. Discussion

4.1. Daily Routine and Care Activities of ICs and Available Support

4.2. Overall Technology and the DemiCare Integrated System: The Perspectives of ICs and PwD

4.3. Functionalities and Properties of the DemiCare Integrated System: The Perspective of HPs

4.4. Ethical Issues and Privacy When Older PwD Are Involved

4.5. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAL | Active and assisted living |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| App | Application |

| CAQDAS | Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software |

| EU | End user |

| GDPR | General data protection regulation |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GRIPP | Guidance for Reporting the Involvement of Patients and the Public |

| HB | High burden |

| HP | Healthcare professional |

| IC | Informal caregiver |

| ISTAT | Italian National Institute of Statistics |

| LB | Low burden |

| LTC | Long-term care |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| MCW | Migrant care worker |

| MD | Mild dementia |

| MoD | Moderate dementia |

| PwD | People with dementia |

| SRQR | Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| STROBE | STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/ (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- ISTAT. Popolazione Italiana Residente al 1 Gennaio 2023; ISTAT Geodemo: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: http://demo.istat.it/popres/index.php?anno=2021&lingua=ita (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- EUROSTAT. Population Structure and Ageing; European Commission, Statistics Explained: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Katz, S. Assessing Self-Maintenance: Activities of Daily Living, Mobility, and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1983, 31, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia; WHO, Mental Health and Substance Use: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033245 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Hugo, J.; Ganguli, M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 30, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, E105–E125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer Europe. Dementia in Europe Yearbook 2019: Estimating the Prevalence of Dementia in Europe; Alzheimer Europe: Luxembourg, 2019; Available online: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/alzheimer_europe_dementia_in_europe_yearbook_2019.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Harrison, K.L.; Ritchie, C.S.; Patel, K.; Hunt, L.J.; Covinsky, K.E.; Yaffe, K.; Smith, A.K. Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults with Moderately Severe Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, G.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Arlotti, M. Ageing in Place in Different Care Regimes. The Role of Care Arrangements and the Implications for the Quality of Life and Social Isolation of Frail Older People. DAStU Work. Pap. Ser. 2020, 3, LPS.10. Available online: http://www.lps.polimi.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/WP-Dastu-32020_new-2.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Ranci, C.; Arlotti, M.; Bernardi, L.; Melchiorre, M.G. La Solitudine Dei Numeri Ultimi. Abit. Anziani. 2020, 1, 5–26. Available online: https://www.abitareeanziani.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/AeA_Magazine_01-2020_completo.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Costa, G. Italy: A case of missing reforms but incremental institutional change in Long Term Care. In Reforms in Long Term Care Policies in Europe Investigating Institutional Change and Social Impacts; Ranci, C., Pavolini, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Ienca, M.; Schneble, C.; Kressig, R.W.; Wangmo, T. Digital health interventions for healthy ageing: A qualitative user evaluation and ethical assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, M.; Lukas, S.; Brathwaite, S.; Neave, J.; Henry, H. Aging in Place: Are We Prepared? Dela. J. Public Health 2022, 8, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, W.A.; Ramadhani, W.A.; Harris, M.T. Defining Aging in Place: The Intersectionality of Space, Person, and Time. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, igaa036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricatore, C.; Radovic, D.; Lopez, X.; Grasso-Cladera, A.; Salas, C.E. When technology cares for people with dementia: A critical review using neuropsychological rehabilitation as a conceptual framework. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2019, 30, 1558–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.I.; Gollamudi, S.S.; Steinhubl, S. Digital technology to enable aging in place. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 88, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchiorre, M.G.; Papa, R.; Rijken, M.; van Ginneken, E.; Hujala, A.; Barbabella, F. eHealth in Integrated Care Programs for People with Multimorbidity in Europe: Insights from the ICARE4EU Project. Health Policy 2018, 122, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.C.; Tobin, S.S.; Robertson-Tchabo, E.A.; Power, P.W. Strengthening Aging Families: Diversity in Practice and Policy; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, K.; Bowman, S.R.; Coehlo, D.P.; Lim, S.R.; Kaye, J.; Guariglia, R.; Li, F. Behavioral change in persons with dementia: Relationships with mental and physical health of caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, P453–P460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaliano, P.P.; Zhang, J.; Scanlan, J.M. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 946–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.A.; Spilsbury, K.; Hall, J.; Birks, Y.; Barnes, C.; Adamson, J. Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2007, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okabayashi, H.; Sugisawa, H.; Takanashi, K.; Nakatani, Y.; Sugihara, Y.; Hougham, G.-W. A longitudinal study of coping and burnout among Japanese family caregivers of frail elders. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, Y.; Higgs, P.; Charlesworth, G. What do we require from surveillance technology? A review of the needs of people with dementia and informal caregivers. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2019, 6, 2055668319869517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, S.; de Witte, L.; Hawley, M. Exploring the Potential of Emerging Technologies to Meet the Care and Support Needs of Older People: A Delphi Survey. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisado-Fernández, E.; Giunti, G.; Mackey, L.M.; Blake, C.; Caulfield, B.M. Factors influencing the adoption of smart health technologies for people with dementia and their informal caregivers: Scoping review and design framework. JMIR Aging 2019, 2, e12192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stara, V.; Rampioni, M.; Mosoi, A.A.; Kristaly, D.M.; Moraru, S.A.; Paciaroni, L.; Paolini, S.; Raccichini, A.; Felici, E.; Rossi, L.; et al. A Technology-Based Intervention to Support Older Adults in Living Independently: Protocol for a Cross-National Feasibility Pilot. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P.; Radnor, Z.; Strokosch, K. Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: A suitable case for treatment? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.; Chong, L.S.; Bundele, A.; Wei Lim, Y. Co-Designing Technology for Aging in Place: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2021, 61, e395–e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, R.; Efthymiou, A.; Lamura, G.; Piccinini, F.; Onorati, G.; Papastavrou, E.; Tsitsi, T.; Casu, G.; Boccaletti, L.; Manattini, A.; et al. Review and Selection of Online Resources for Carers of Frail Adults or Older People in Five European Countries: Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e14618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Marradi, C.; Albayrak, A.; van der Cammen, T.J. Co-designing with people with dementia: A scoping review of involving people with dementia in design research. Maturitas 2019, 127, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, N.; Truyen, F.; Duval, E. Designing with dementia: Guidelines for participatory design together with persons with dementia. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2013, 8117, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopman, D.S.; Petersen, R.C. Mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: A clinical perspective. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, N.; Manthorpe, J.; Sampson, E.L.; Lamahewa, K.; Wilcock, J.; Mathew, R.; Iliffe, S. Guiding practitioners through end of life care for people with dementia: The use of heuristics. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.; Tanghe, D.; Pratt, W.; Ralston, J. Collaborative Health Reminders and Notifications: Insights from Prototypes. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2018, 2018, 837–846. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, P.A. Co-designing with people living with dementia. CoDesign 2018, 14, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, K.; Kelleher, D.; Ogden, M.; Mason, C.; Rapaport, P.; Burton, A.; Leverton, M.; Downs, M.; Souris, H.; Jackson, J.; et al. Co-designing complex interventions with people living with dementia and their supporters. Dementia 2022, 21, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeates, L.; Gardner, K.; Do, J.; van den Heuvel, L.; Fleming, G.; Semsarian, C.; McEwen, A.; Adlard, L.; Ingles, J. Using co-design focus groups to develop an online COmmunity suPporting familiEs after Sudden Cardiac Death (COPE-SCD) in the young. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, C.; Bruce, E. Successes and challenges in using focus groups with older people with dementia. In The Perspectives of People with Dementia: Research Methods and Motivations; Wilkinson, H., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2002; pp. 139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M.R.; Meulen, R. Recommendations for Involving People with Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment and Their Informal Caregivers and Relatives in the Assisted Living Project; University of Bristol, Centre for Ethics in Medicine: Bristol, UK, 2018; Available online: https://uni.oslomet.no/assistedliving/wp-content/uploads/sites/889/2018/11/alproject_methods_recs_v2_f.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J. (Eds.) Qualitative Research Practice. A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Figueroa, M.C.; Ruckhaus, E.; López-Guerrero, J.; Cano, I.; Cervera, Á. Towards the Assessment of Easy-To-Read Guidelines Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. In Proceedings of the Computers Helping People with Special Needs: 17th International Conference, ICCHP 2020, Lecco, Italy, 9–11 September 2020; Volume 12376, pp. 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, M. Formality and Friendship: Research Ethics Review and Participatory Action Research. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2007, 6, 411–421. Available online: https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/789/648 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Goodyear-Smith, F.; Jackson, C.; Greenhalgh, T. Co-design and implementation research: Challenges and solutions for ethics committees. BMC Med. Ethics 2015, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. General Data Protection Regulation. Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, 679, L 119/1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Levers, M.J.D. Philosophical Paradigms, Grounded Theory, and Perspectives on Emergence. Sage Open Publ. 2013, 3, 2158244013517243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A.L. (Eds.) The Discovery of Grounded Theory Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J.D. L’apprendimento Significativo; Edizioni Centro Studi Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Caspar, S.; Garschall, M.; Sfetcu, R.; Himmelsbach, J.; Fass, F. SUccessful Caregiver Communication and Everyday Situation Support in dementia care (SUCCESS): Using technology to support caregivers. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, e041310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2022 [Computer Software]; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://maxqda.com (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Carcary, M. Evidence Analysis Using CAQDAS: Insights from a Qualitative Researcher. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2011, 9, 10–24. Available online: https://academic-publishing.org/index.php/ejbrm/article/view/1264/1227 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Gibbs, G.R. Using Software in Qualitative Analysis. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniszewska, S.; Brett, J.; Simera, I.; Seers, K.; Mockford, C.; Goodlad, S.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Barber, R.; Denegri, S.; et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: Tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 2017, 358, j3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, R.; Eden, J. (Eds.) Families Caring for an Aging America; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grynne, A.; Browall, M.; Fristedt, S.; Ahlberg, K.; Smith, F. Integrating perspectives of patients, healthcare professionals, system developers and academics in the co-design of a digital information tool. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biderman, A.; Carmel, S.; Amar, S.; Bachner, Y.G. Care for caregivers- a mission for primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Fraile, E.; Ballesteros, J.; Rueda, J.R.; Santos-Zorrozúa, B.; Solà, I.; McCleery, J. Remotely delivered information, training and support for informal caregivers of people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, CD006440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R.; Czaja, S.J.; Martire, L.M.; Monin, J.K. Family Caregiving for Older Adults. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, V.; Jenkinson, C.; Peters, M. Informal carers’ experience of assistive technology use in dementia care at home: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, V.; Pierce, L.L.; Salvador, D. Information Needs of Family Caregivers of People with Dementia. Rehabil. Nurs. 2016, 41, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.; Hahn, H.; Lee, A.J.; Madison, C.A.; Atri, A. In the Information Age, do dementia caregivers get the information they need? Semi-structured interviews to determine informal caregivers’ education needs, barriers, and preferences. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixsmith, A.; Gutman, G. Technologies for Active Aging, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, D.; Rusu, D.; Bacali, L.; Popescu, S. Multi-Layered Functional Analysis for Smart Homes Design. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2018, 238, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, A.; Villalba-Mora, E.; Pérez-Rodríguez, R.; Ferre, X.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Unobtrusive Sensors for the Assessment of Older Adult’s Frailty: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Brinke, J.K.; Van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C.; Braakman-Jansen, L.M.A. Implementation of Unobtrusive Sensing Systems for Older Adult Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Aging 2021, 4, e27862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pot, A.M.; Willemse, B.M.; Horjus, S. A pilot study on the use of tracking technology: Feasibility, acceptability, and benefits for people in early stages of dementia and their informal caregivers. Aging Ment. Health 2012, 16, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.R.; Min, E.E.; Abebe, E.; Holden, R.J. Telecaregiving for dementia: A mapping review of technological and non-technological interventions. Gerontologist 2023, gnad026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cruz, A.M.; Ruptash, T.; Barnard, S.; Juzwishin, D. Acceptance of global positioning system (GPS) technology among dementia clients and family caregivers. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2017, 35, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelcic, N.; Agostini, M.; Meneghello, F.; Bussè, C.; Parise, S.; Galano, A.; Tonin, P.; Dam, M.; Busse, C. Feasibility and efficacy of cognitive telerehabilitation in early Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E.; Magnusson, L.; Arvidsson, H.; Claesson, A.; Keady, J.; Nolan, M. Working together with persons with early stage dementia and their family members to design a user-friendly technology-based support service. Dementia 2007, 6, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, C.; Turner, N.R.; Liu, L.; Karras, S.W.; Chen, A.; Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.; Demiris, G. Advance Planning for Technology Use in Dementia Care: Development, Design, and Feasibility of a Novel Self-administered Decision-Making Tool. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e39335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, L.; Innes, A. Supporting safe walking for people with dementia: User participation in the development of new technology. Gerontechnology 2013, 12, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, R.; Auslander, G.K.; Werner, S.; Shoval, N.; Heinik, J. Who should make the decision on the use of GPS for people with dementia? Aging Ment. Health 2011, 15, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stara, V.; Vera, B.; Bolliger, D.; Paolini, S.; de Jong, M.; Felici, E.; Koenderink, S.; Rossi, L.; Von Doellen, V.; di Rosa, M. Toward the Integration of Technology-Based Interventions in the Care Pathway for People with Dementia: A Cross-National Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, A.; Engström, M.; Skovdahl, K.; Lampic, C. My, your and our needs for safety and security: Relatives’ reflections on using information and communication technology in dementia care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 26, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rettinger, L.; Zeuner, L.; Werner, K.; Ritschl, V.; Mosor, E.; Stamm, T.; Haslinger-Baumann, E.; Werner, F. A mixed-methods evaluation of a supporting app for informal caregivers of people with dementia. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, Corfu, Greece, 30 June–3 July 2020; Volume 46, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajenaru, L.; Ianculescu, M.; Dobre, C. A Holistic Approach for Creating a Digital Ecosystem Enabling Personalized Assistive Care for Elderly, 16th International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing; IEEE: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328686965_A_Holistic_Approach_for_Creating_a_Digital_Ecosystem_Enabling_Personalized_Assistive_Care_for_Elderly (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Wan, L.; Muller, C.; Randall, D.; Wulf, V. Design of a GPS monitoring system for dementia care and its challenges in academia-industry project. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2016, 23, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiura, Y.; Nihei, M.; Nakamura-Thomas, H.; Inoue, T. Effectiveness of using assistive technology for time orientation and memory, in older adults with or without dementia. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 16, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, C.K.; Condell, J.; Dora, S.; Gibson, D.S.; Leavey, G. State-of-the-art sensors for remote care of people with dementia during a pandemic: A systematic review. Sensors 2021, 21, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQudah, A.A.; Al-Emran, M.; Shaalan, K. Technology Acceptance in Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Peng, S.; Jiang, X.; Xu, K.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Dai, C.; Chen, W. A review of wearable and unobtrusive sensing technologies for chronic disease management. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 129, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrede, C.; Braakman-Jansen, A.; van Gemert-Pijnen, L. How to create value with unobtrusive monitoring technology in home-based dementia care: A multimethod study among key stakeholders. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, S.; Wyndham-West, M.; Mulvale, G.; Park, S.; Buettgen, A.; Phoenix, M.; Fleisig, R.; Bruce, E. Are you really doing ‘codesign’? Critical reflections when working with vulnerable populations. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastall, M.R.; Eiermann, N.D.; Ritterfeld, U. Formal and informal carers’ views on ICT in dementia care: Insights from two qualitative studies. Gerontechnology 2014, 13, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Society. Dementia-Friendly Focus Groups; Dementia Support: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/dementia-professionals/dementia-experience-toolkit/research-methods/dementia-friendly-focus-groups (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Bogza, L.; Patry-Lebeau, C.; Farmanova, E.; Witteman, H.O.; Elliott, J.; Stolee, P.; Hudon, C.; Giguere, A.M.C. User-Centered Design and Evaluation of a Web-Based Decision Aid for Older Adults Living with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Their Health Care Providers: Mixed Methods Study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2020, 22, e17406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants | Questions |

|---|---|

| Focus group 1—ICs | What does a typical week look like in terms of daily and care activities? |

| When do you experience burden and why? | |

| Do you need more information on care management? | |

| From whom (e.g., family and services) do you have support? | |

| Could technology be useful in supporting caregiving? | |

| Focus group 2—ICs and older PwD | Which smart devices do you use in your daily routine? |

| What could convince you to use or not use them? | |

| What are your opinions/expectations regarding technology? | |

| What are your opinions/expectations regarding the DemiCare system? | |

| How can the DemiCare system remind you to use it? | |

| Focus group 3—HPs | What is your first impression of the overall vision of DemiCare for providing smart devices for PwD and app-based guidance for ICs? |

| What about the wearability and personalization factors of the devices and app? | |

| How do you think ICs and PwD could benefit from the DemiCare system? What would motivate you to act in this respect? | |

| Are you aware of any similar support available on the market? |

| N. | HPs Involved |

|---|---|

| 1 | Psychologist: cognitive disorders, diagnostics, and rehabilitation of older patients |

| 2 | Psychologist: cognitive disorders, diagnostics, and training course for family caregivers |

| 3 | Psychologist: coordination of home services for PwD and AD care |

| 4 | Neuropsychologist: cognitive disorders, diagnostics, and rehabilitation of older patients |

| 5 | Biomedical engineer: experience with AAL projects on dementia |

| 6 | Health social worker: responsible for social policies in the Marche region (Italy) and support for family caregivers |

| 7 | Medical doctor: specialization in psychotherapy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gris, F.; D’Amen, B.; Lamura, G.; Paciaroni, L.; Socci, M.; Melchiorre, M.G. Personalized Technological Support for Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Co-Design Approach Involving Potential End Users and Healthcare Professionals in Three Focus Groups in Italy. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192640

Gris F, D’Amen B, Lamura G, Paciaroni L, Socci M, Melchiorre MG. Personalized Technological Support for Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Co-Design Approach Involving Potential End Users and Healthcare Professionals in Three Focus Groups in Italy. Healthcare. 2023; 11(19):2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192640

Chicago/Turabian StyleGris, Francesca, Barbara D’Amen, Giovanni Lamura, Lucia Paciaroni, Marco Socci, and Maria Gabriella Melchiorre. 2023. "Personalized Technological Support for Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Co-Design Approach Involving Potential End Users and Healthcare Professionals in Three Focus Groups in Italy" Healthcare 11, no. 19: 2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192640

APA StyleGris, F., D’Amen, B., Lamura, G., Paciaroni, L., Socci, M., & Melchiorre, M. G. (2023). Personalized Technological Support for Informal Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Co-Design Approach Involving Potential End Users and Healthcare Professionals in Three Focus Groups in Italy. Healthcare, 11(19), 2640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192640