The Moderating Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Job Embeddedness, Organizational Commitment, and Retention Intention among Home Care Attendants in Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

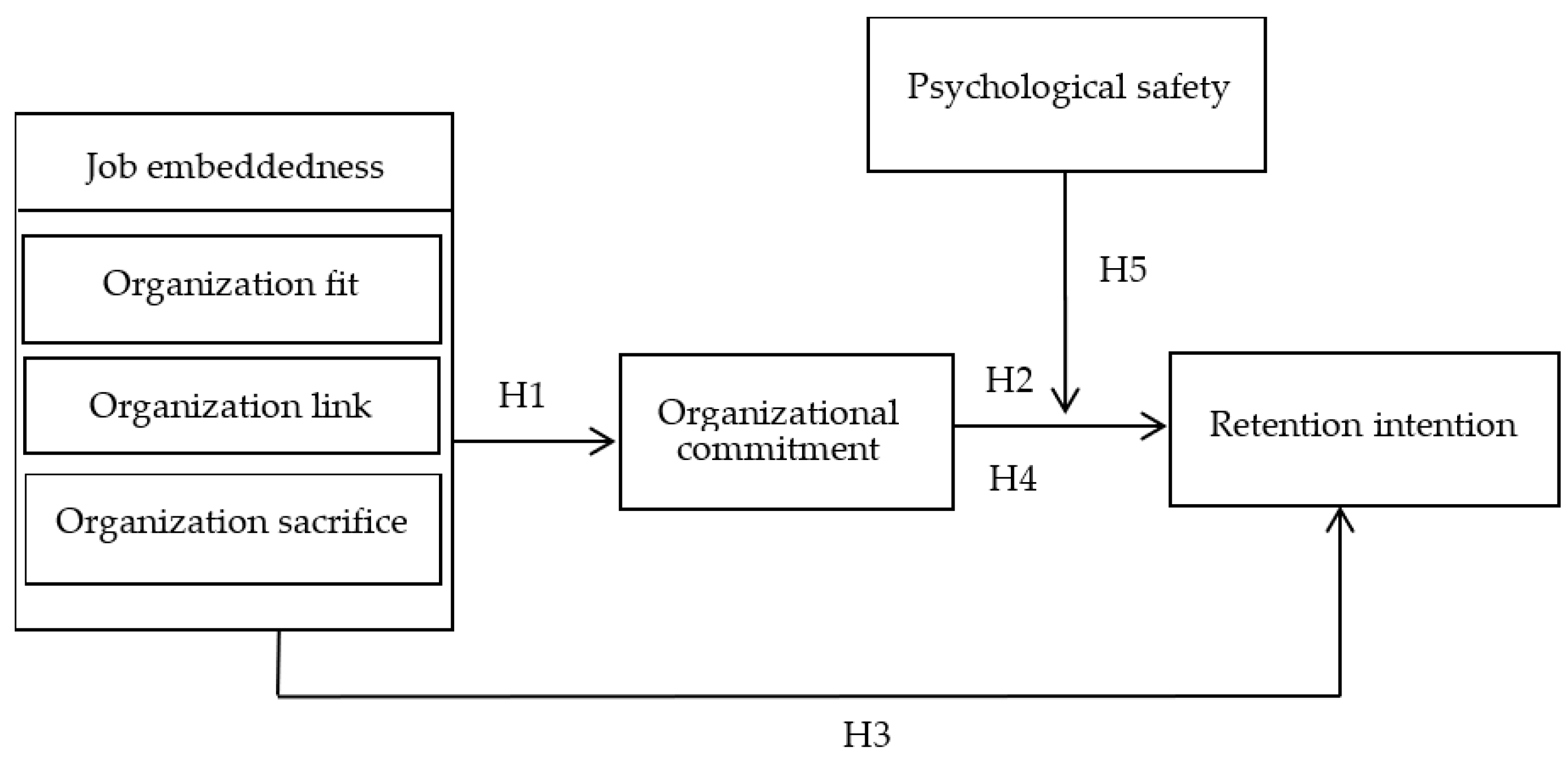

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Job Embeddedness

2.2.2. Organizational Commitment

2.2.3. Retention Intention

2.2.4. Psychological Safety

2.3. Research Questionnaire Design

2.4. Sample and Data Collection

2.5. Techniques for Analyzing the Data

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Model: Test Results

3.2. Structural Model Evaluation

3.3. Mediation Effects Testing

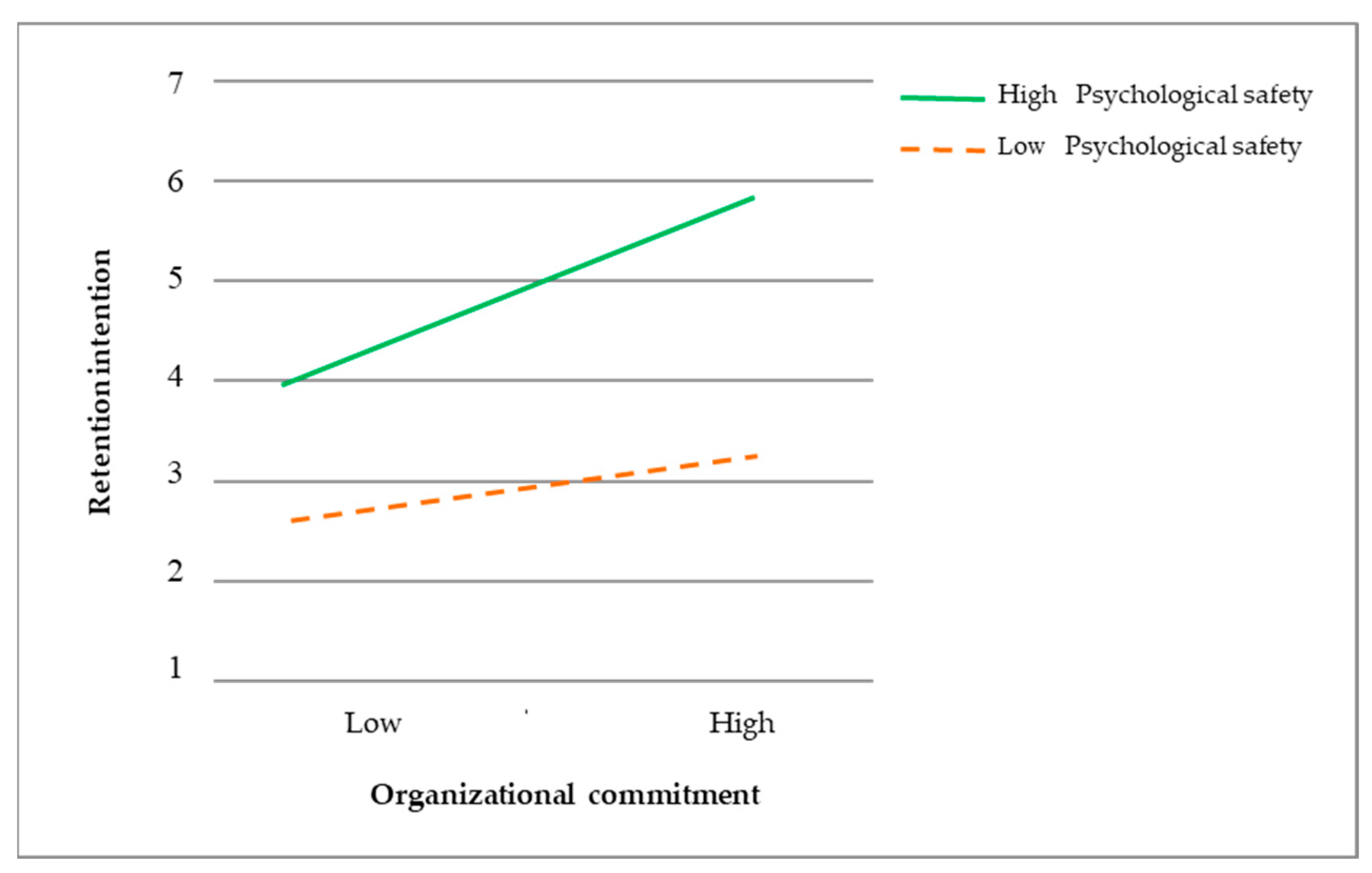

3.4. Moderation Effects Testing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Management Implications

5.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Directions for Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Development Council. Population Estimate Report of the Republic of China (2022~2070); National Development Council: Taipei, Taiwan, 2022.

- Taiwan Aging Index, Ministry of the Interior Global Information Network. Retrieved on 8 June 2022. Available online: https://www.moi.gov.tw/cp.aspx?n=602&ChartID=S0401 (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Report on the Elderly Status Survey in the Republic of China for the Year. 2017; Ministerial Long-Term Care Special Section, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://1966.gov.tw/LTC/lp-3948-201.html (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare Implementation and Prospects of Long-Term Care 2.0. National Health Research Institutes Forum. 2021. Available online: https://forum.nhri.edu.tw/wp-content/uploads/20210202.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Katsuro, I. The reality of home caregivers under the long-term care restraint policy. J. Jpn. Soc. Med. Econ. 2017, 33, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.H. Actual Development Overview of Domestic Care Workers and Specific Planning for Government’s Overall Long-Term Care Workforce. Control Yuan. 2020. Available online: https://www.cy.gov.tw/CyBsBoxContent.aspx?n=133&s=6035 (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Chung, L.H.; Lan, F.L. Analysis of the Long-Term Care Industry’s Manpower Structure and Workplace Environment Issues, and Research on Coping Strategies; Institute of Labor and Occupational Safety and Health, Ministry of Labor: New Taipei, Taiwan, 2019.

- Chou, H.T. Labor Shortage in Long-Term Care Institutions: A Case Study of Tainan Area Taiwan. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, The Executive Master of Public Policy Program. Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, M.O. Understanding factors affecting homecare workers’ job retention willingness. Soochow J. Soc. Work 2017, 33, 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Tilse, C.; Wilson, J.; Tuckett, A.; Newcombe, P. Perceptions and employment intentions among aged care nurses and nursing assistants from diverse cultural backgrounds: A qualitative interview study. J. Aging Stud. 2015, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, H.; Walsh, S.; Cooper, C.; Livingston, G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and associations of stress and burnout among staff in long-term care facilities for people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.D.; Harrington, A.; Mavromaras, K.; Ratcliffe, J.; Mahuteau, S.; Isherwood, L.; Gregoric, C. Care workers’ perspectives of factors affecting a sustainable aged care work force. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2020, 68, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Liu, D.; McKay, P.F.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. When and how is job embeddedness predictive of turnover? A meta-analytic investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1077–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ryan, S.D.; Prybutok, V.R.; Kappelman, L. Perceived obsolescence, organizational embeddedness, and turnover of it workers: An empirical study. SIGMIS Database 2012, 43, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; Lee, T.W.; Sablynski, C.J.; Erez, M. Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, C.D.; Bennett, R.J.; Jex, S.M.; Burnfield, J.L. Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, R. Forecasting your organizational climate. J. Property Manag. 2000, 65, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.L.; Martins, N. The relationship between organisational climate and employee satisfaction in a South African information and technology organization. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, O.E. The job embeddedness instrument: An evaluation of validity and reliability. Geriatr. Nurs. 2014, 35, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.M. Job embeddedness may hold the key to the retention of novice talent in schools. Educ. Leadersh. Admin. Teach. Program. Dev. 2018, 29, 26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effects of stress, LMX and perceived organizational support on service quality: Mediating effects of organizational commitment. J. Hosp. Tourism. Manag. 2014, 21, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.A. Human resource management practices and organizational commitment in four- and five-star hotels in Egypt. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.J.; Ao, C.T.D. The mediating effects of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on turnover intention, in the relationships between pay satisfaction and work–family conflict of casino employees. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 20, 206–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jønsson, T.; Jeppe Jeppesen, H.J. A closer look into the employee influence: Organizational commitment relationship by distinguishing between commitment forms and influence sources. Empl. Relat. 2012, 35, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohana, M.; Meyer, M. Distributive justice and affective commitment in nonprofit organizations: Which referent matters? Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungu, L.J.; Weng, Q.; Xu, X. Organizational commitment and job performance: Examining the moderating roles of occupational commitment and transformational leadership Lincoln. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2019, 27, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, S.; Shafi, A.; Qun, W.; Nazir, N.; Tran, Q.D. Influence of organizational rewards on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 596–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top, M.; Gider, O. Interaction of organizational commitment and job satisfaction of nurses and medical secretaries in Turkey. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Moqbel, M. Social networking site use, positive emotions, and job performance. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2021, 61, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.; Coetzee, M. Psychological career resources as predictors of employees’ job embeddedness: An exploratory study. S. Afr. J. Lab. Relat. 2014, 38, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shehawy, Y.M.; Elbaz, A.; Agag, G.M. Factors affecting employees’ job embeddedness in the Egyptian airline industry. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Y.; Noor, A. The role of job embeddedness and organizational continuance commitment on intention to stay: Development of research framework and hypotheses. Soc. Sci. 2019, 3, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, J.; Yean, T.F.; Adnan, Z.; Yahya, K.K.; Ahmad, M.N. Promoting employee intention to stay: Do human resource management practices matter. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2012, 6, 396–416. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee, M.; Stoltz, E. Employees’ satisfaction with retention factors: Exploring the role of career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamdan, Z.; Nussera, H.; Masa’deh, R. Conflict management style of Jordanian nurse managers and its relationship to staff nurses’ intent to stay. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, E137–E145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowin, L. Measuring nurses’ self-concept. West J. Nurs. Res. 2001, 23, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, F.; Kurniati, A.; Bushy, A.; Gunawan, J. Concept analysis of nurse retention. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardanov, I. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, organizational context, employee contentment, job satisfaction, performance and intention to stay. In Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, M.; Herrera, J.; de las Heras-Rosas, C. Model of organizational commitment applied to health management systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, M.; Sheridan, A. How organisational commitment influences nurses’ intention to stay in nursing throughout their career. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2020, 2, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowden, T.; Cummings, G.; Profetto-McGrath, J. Leadership practices and staff nurses’ intent to stay: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2011, 19, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, A.; Patterson, E.; Rowe, A.; Saari, M.; Thomson, H.; MacDonald, G.; Cranley, L.; Squires, M. Factors influencing home care nurse intention to remain employed. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perryer, C.; Jordan, C.; Firns, I.; Travaglione, A. Predicting turnover intentions: The interactive effects of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzeller, C.O.; Celiker, N. Examining the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention via a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 14, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Mero, N.; Werner, S. The negative effects of job embeddedness on performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surie, G.; Ashley, A. Integrating pragmatism and ethics in entrepreneurial leadership for sustainable value creation. J. Bus Ethics 2008, 81, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, A.; Inma, C.; Poisat, P.; Redmond, J.; Standing, C. Does job embeddedness predict turnover intentions in SMEs? Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, I.M.; Brantley-Dias, L.; Lokey-Vega, A. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention of online teachers in the K-12 setting. J. Asynchronous Learn Netw. 2016, 20, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanova, C.; Holtom, B.C. Using job embeddedness factors to explain voluntary turnover in four European countries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1553–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Sharan, K.; Wei, J. New development of organizational commitment: A critical review (1960–2009). Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 012–020. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithson, J.; Lewis, S. Is job insecurity changing the psychological contract? Pers. Rev. 2000, 29, 680–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Admin. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard-Barton, D.; Swap, W.C. Deep Smarts: How to Cultivate and Transfer Enduring Business Wisdom; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Gittell, J.H. High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J. Organiz. Behav. 2009, 30, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Lei, Z. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Donohue, R.; Eva, N. Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H.A.H.; Jayaeathua, S.M.D.Y. The effect of employer work related attitudes on employee job performance: A study of tertiary and vocational education sector in Sri Lanka. J. Bus Manag. 2014, 16, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Deery, M.; Jago, L. Revisiting talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.S.; Kralj, A.; Solnet, D.J.; Goh, E.; Callan, V. Thinking job embeddedness not turnover: Towards a better understanding of frontline hotel worker retention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, B.S.; Freund, A.M.; Baltes, P.B. Subjective career success and emotional well-being: Longitudinal predictive power of selection, optimization, and compensation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk-Brown, A.; Van Dijk, P. An examination of the role of psychological safety in the relationship between job resources, affective commitment and turnover intentions of Australian employees with chronic illness. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1626–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Bakker, A.B. Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.; Frese, M. Innovation is not enough: Climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. J. Organiz. Behav. 2003, 24, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y. Understanding the Link Between Work-Related and Non-Work-Related Supervisor–Subordinate Relationships and Affective Commitment: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Psychological Safety. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag 2022, 15, 1649–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Sablynski, C.J.; Burton, J.P.; Holtom, B.C. The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtom, B.C.; Inderrieden, E.J. Integrating the unfolding model and job embeddedness model to better understand voluntary turnover. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 435–452. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbacher, C.; Chappel, D.; Edwards, R.; Summerton, N. Health surveys via the internet: Quick and dirty or rapid and robust? J. R. Soc. Med. 2000, 93, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Leesenberg, L.; Lafreniere, K.; Dumula, R. The internet: An effective tool for nursing research with women. Comput. Nurs. 2000, 18, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.L. Structural Equation Modeling: AMOS Operation and Application; Wu-Nan Book: Taipei, Taiwan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K.; Rockwood, N.J. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: Process versus structural equation modeling. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hussain, I.; Akram, S.; Afaq, A.; Shad, M.A. Sustainable Innovation in Small Medium Enterprises: The Impact of Knowledge Management on Organizational Innovation through a Mediation Analysis by Using SEM Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Lakshmi, K.S.; Tongkachok, K.; Alanya-Beltran, J.; Ramirez-Asis, E.; Perez-Falcon, J. Empirical analysis in analysing the major factors of machine learning in enhancing the e-business through structural equation modelling (SEM) approach. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2022, 13, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.U.; Hamid, M.A. Measurement of CSR Performance in Manufacturing Industries: A SEM Approach. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gieter, S.; Hofmans, J.; Pepermans, R. Revisiting the impact of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on nurse turnover intention: An individual differences analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, A.H.; Froese, F.J.; Pak, Y.S. Lessening the divide in foreign subsidiaries: The influence of localization on the organizational commitment and turnover intention of host country nationals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.D.; Griffeth, R.W.; Allen, D.G.; Lee, M.B. Comparing operationalizations of dual commitment and their relationships with turnover intentions. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1342–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peachey, J.W.; Burton, L.J.; Wells, J.E. Examining the influence of transformational leadership, organizational commitment, job embeddedness, and job search behaviors on turnover intentions in intercollegiate athletics. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2014, 35, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Vatankhah, S. The effects of high-performance work practices and job embeddedness on flight attendants’ performance outcomes. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2014, 37, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Frequency (n = 458) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 143 | 31.22% |

| Female | 315 | 68.88% | |

| Age | 20–29 | 36 | 7.86% |

| 30–39 | 77 | 16.81% | |

| 40–49 | 118 | 25.76% | |

| 50–59 | 166 | 36.25% | |

| 60 or above | 61 | 13.32% | |

| Education Level | Junior high school or below | 214 | 46.72% |

| Junior college degree | 157 | 34.28% | |

| Undergraduate degree | 48 | 10.48% | |

| Master’s degree (inclusive) and above | 39 | 8.52% | |

| Personal Monthly Income (NTD) | Less than NTD 20,000 | 37 | 8.08% |

| NTD 20,001–30,000 | 95 | 20.73% | |

| NTD 30,001–40,000 | 148 | 32.31% | |

| NTD 40,001–50,000 | 121 | 26.42% | |

| NTD 50,001–60,000 | 48 | 10.46% | |

| Above NTD 60,001 | 9 | 2.00% | |

| Decades of Job Expertise | Less than 1 year | 85 | 18.56% |

| 1~3 years | 165 | 36.03% | |

| 3~5 years | 66 | 14.41% | |

| 5~7 years | 37 | 8.08% | |

| 7~10 years | 48 | 10.48% | |

| 10 years or more (including) | 57 | 12.44% | |

| Types of Caregiving Services | Nursing home | 19 | 4.15% |

| Long-term care facility | 36 | 7.86% | |

| Hospice | 44 | 9.61% | |

| Hospital ward one-on-one care | 62 | 13.54% | |

| Home care service agency | 283 | 61.78% | |

| Other | 14 | 3.06% |

| Variables | Items | Standardized Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job embeddedness | Organizational fit | 1. My current job effectively utilizes my talents. | 0.826 *** | 0.915 | 0.782 | 0.912 |

| 2. I believe I am well-suited for my current position in the home care organization. | 0.848 *** | |||||

| 3. I perceive that the home care organization I work for highly values my employment. | 0.825 *** | |||||

| 4. I appreciate the scheduling arrangement of my present job. | 0.817 *** | |||||

| 5. I find satisfaction in collaborating with colleagues at the current home care organization. | 0.829 *** | |||||

| 6. I derive fulfillment from my current role within the home care organization. | 0.834 *** | |||||

| 7. My principles align with the philosophy upheld by this home care organization. | 0.873 *** | |||||

| 8. This job draws upon my skills and abilities. | 0.861 *** | |||||

| 9. I am a good fit for the corporate culture of this home care organization. | 0.837 *** | |||||

| 10. In the future, I aspire to assume greater authority and responsibility within this home care organization. | 0.881 *** | |||||

| Organizational links | 11. I frequently have positive interactions with my colleagues during work hours. | 0.816 *** | 0.846 | 0.714 | ||

| 12. Following work, I actively engage in conversations or activities alongside my colleagues. | 0.772 *** | |||||

| 13. I discover that my colleagues actively participate together in the various events organized by our healthcare institution. | 0.862 *** | |||||

| Organizational sacrifice | 14. My colleagues demonstrate a high level of respect towards me. | 0.802 *** | 0.892 | 0.725 | ||

| 15. The present salary is satisfactory to me. | 0.815 *** | |||||

| 16. I hold the view that remaining employed at this home care establishment offers promising opportunities. | 0.846 *** | |||||

| 17. Departing from this establishment would entail compromising the reliance others place on me. | 0.828 *** | |||||

| 18. I am ready to enhance my job skills for the betterment of this home care institution. | 0.803 *** | |||||

| 19. This job encompasses numerous benefits. | 0.826 *** | |||||

| 20. The home care institution I am affiliated with offers commendable employee benefits. | 0.871 *** | |||||

| Organizational commitment | Affective commitment | 1. I plan to work at this home care facility for the entirety of my professional journey. | 0.805 *** | 0.862 | 0.692 | 0.894 |

| 2. I am pleased to engage in conversations about the home care facility I am employed at with individuals external to the organization. | 0.774 *** | |||||

| 3. I have confidence in my ability to seamlessly transition my loyalty to a different home care institution. | 0.732 *** | |||||

| 4. This home care facility carries immense personal importance to me. | 0.815 *** | |||||

| Continuance commitment | 5. Although I have not secured an alternate job yet, I fearlessly accept the repercussions of quitting my present role. | 0.838 *** | 0.927 | 0.801 | ||

| 6. Departing from this nursing home is an arduous task, making it challenging for me to submit my resignation, even if I desire to do so. | 0.924 *** | |||||

| 7. Opting to resign from this nursing home would introduce numerous disruptions in my life. | 0.891 *** | |||||

| 8. I will persist in working at this nursing home due to the substantial personal sacrifices associated with resigning and the inability of another organization to offer me all the current benefits I enjoy. | 0.927 *** | |||||

| Normative commitment | 9. I will persist at this care facility as I am committed to upholding workplace ethics. | 0.896 *** | 0.874 | 0.793 | ||

| 10. Even with a more enticing job offer, I would not deem leaving this care institution as the correct choice. | 0.863 *** | |||||

| 11. I have been instilled with the principle of remaining loyal to the company organization. | 0.958 *** | |||||

| Retention intention | 1. I am ready to stay at the present home care institution and take on the given assignments. | 0.843 *** | 0.865 | 0.706 | 0.896 | |

| 2. I firmly believe that serving in this institution is the correct decision. | 0.827 *** | |||||

| 3. The existing work conditions and environment offered by this home care institution motivate me to continue with my tenure in the foreseeable future. | 0.861 *** | |||||

| 4. Even if I were to terminate my involvement in the current case service, I would still not contemplate leaving this home care institution, and there would be a chance to transition to another institution. | 0.842 *** | |||||

| 5. Pursuing my career in this home care institution would greatly aid my future career plans. | 0.794 *** | |||||

| Psychological safety | 1. My colleagues at the home care organization I work for are inclined to share information rather than hoard it. | 0.820 *** | 0.917 | 0.828 | 0.864 | |

| 2. Collaboration and teamwork take precedence among the team members at the home care organization I work for. | 0.881 *** | |||||

| 3. The team members at the home care organization I work for exert influence on one another. | 0.915 *** | |||||

| 4. Communication and discussion regarding work-related matters occur among the team members at the home care organization I work for. | 0.849 *** | |||||

| 5. The team members at the home care organization I work for are readily understood and accepted by their peers. | 0.853 *** | |||||

| 6. Even when expressing immature perspectives, the team members at the home care organization I work for receive due consideration. | 0.928 *** | |||||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational fit | 5.102 | 0.719 | 0.725 | |||||

| Organizational links | 5.712 | 1.118 | 0.232 ** | 0.799 | ||||

| Organizational sacrifice | 5.003 | 1.002 | 0.717 ** | 0.237 ** | 0.810 | |||

| Organizational commitment | 5.381 | 0.791 | 0.441 ** | 0.129 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.789 | ||

| Retention intention | 4.437 | 1.465 | 0.339 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.829 | |

| Psychological safety | 5.543 | 0.726 | 0.528 ** | 0.215 ** | 0.543 ** | 0.698 ** | 0.452 ** | 0.784 |

| Hypothesis | γ | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1 | Organizational fit → Organizational commitment | 0.649 | Supported |

| H1-2 | Organizational links → Organizational commitment | 0.607 | Supported |

| H1-3 | Organizational sacrifice → Organizational commitment | 0.628 | Supported |

| H2 | Organizational commitment → Retention intention | 0.721 | Supported |

| H3-1 | Organizational fit → Retention intention | 0.253 | Supported |

| H3-2 | Organizational links → Retention intention | 0.242 | Supported |

| H3-3 | Organizational sacrifice → Retention intention | 0.271 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4-1 | Organizational fit→ Retention intention | 0.258 | 0.469 | Supported |

| H4-2 | Organizational links→ Retention intention | 0.249 | 0.442 | Supported |

| H4-3 | Organizational sacrifice→ Retention intention | 0.274 | 0.455 | Supported |

| Variables | Retention Intention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Step 1: Independent variable | |||

| Organizational commitment | 0.717 *** | 0.249 | 0.131 |

| Step 2: Moderator | |||

| Psychological safety | 0.625 *** | 0.341 *** | |

| Step 3: Retention intention | |||

| Organizational commitment × Psychological safety | 0.639 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.168 | 0.242 | 0.268 |

| ΔR2 | 0.062 | 0.018 | |

| F | 45.003 *** | 35.371 *** | 24.624 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, M.-Y.; Fu, C.-K.; Huang, C.-F.; Chen, H.-S. The Moderating Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Job Embeddedness, Organizational Commitment, and Retention Intention among Home Care Attendants in Taiwan. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182567

Chang M-Y, Fu C-K, Huang C-F, Chen H-S. The Moderating Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Job Embeddedness, Organizational Commitment, and Retention Intention among Home Care Attendants in Taiwan. Healthcare. 2023; 11(18):2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182567

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Min-Yen, Chih-Kuang Fu, Chi-Fu Huang, and Han-Shen Chen. 2023. "The Moderating Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Job Embeddedness, Organizational Commitment, and Retention Intention among Home Care Attendants in Taiwan" Healthcare 11, no. 18: 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182567

APA StyleChang, M.-Y., Fu, C.-K., Huang, C.-F., & Chen, H.-S. (2023). The Moderating Role of Psychological Safety in the Relationship between Job Embeddedness, Organizational Commitment, and Retention Intention among Home Care Attendants in Taiwan. Healthcare, 11(18), 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182567