An Integrative Review of the Influence on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Adherence among Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

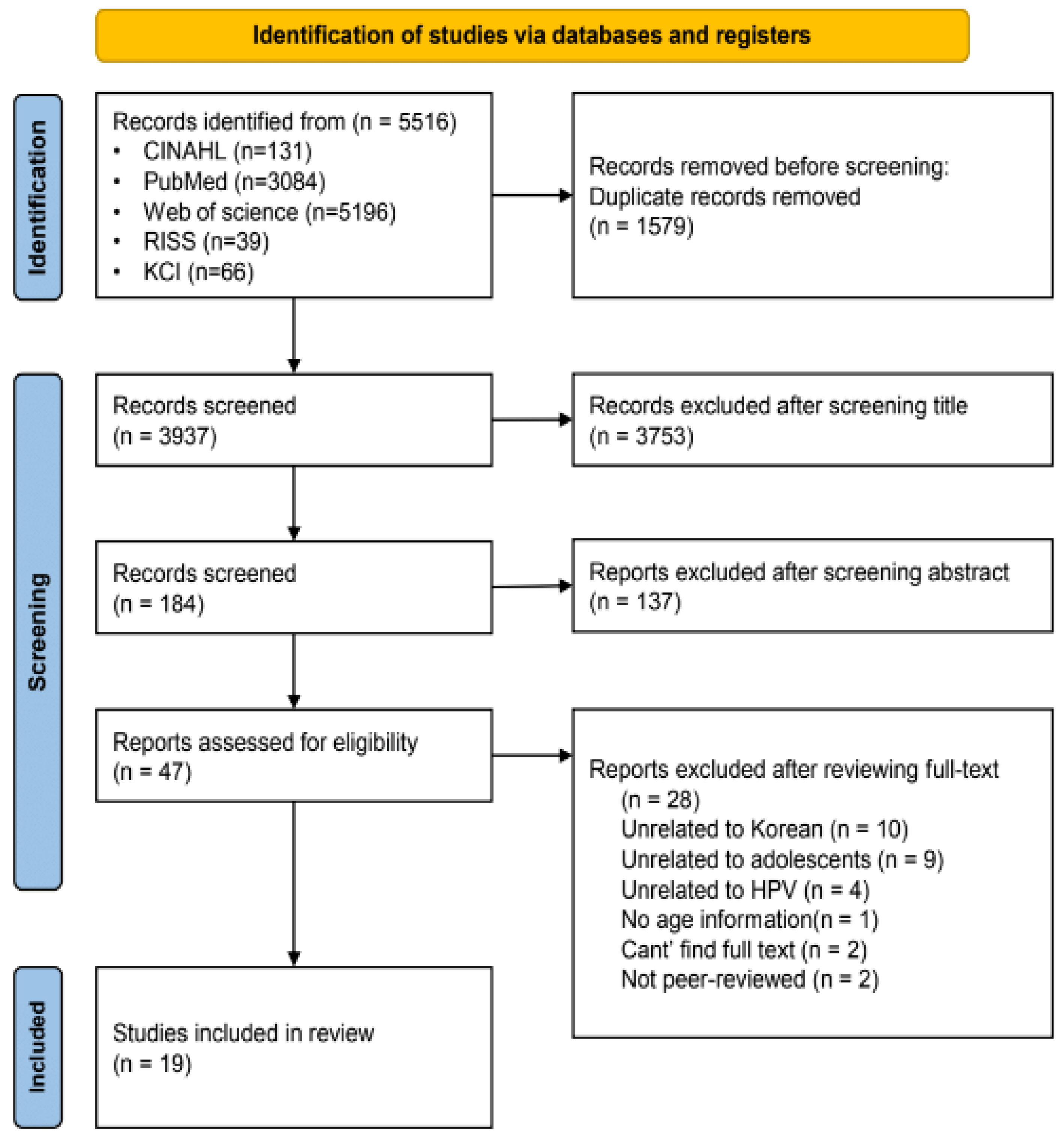

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Quality Appraisal

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

| Author (Year) | Methods | Sample | Purpose | Findings (Vaccination—a. Rate, b. Intention, c. Knowledge, d. Attitude, e. Others) (n/%/Mean) | Findings (Independent/Dependent Variable) | Strengths/ Limitations | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi & Park (2016) [25] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 495 male students (high school and university students) | To survey the current state of HPV vaccination and the predictors of vaccination intention among Korean male students of high school (ages 15–19) and university (ages 17–27). | a. very low. 2.4% (ex. 12 students out of 495) c. low. 11.76 out of 100 e. overall health belief: low. 2.18 out of 4 | The significant predictors promoting the intention of HPV vaccination were university students, the experience of sexual intercourse, and perceiving the benefit of HPV vaccination. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling | 80% |

| Choi & Cheon (2015) [26] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 492 female adolescents (middle and high school) | To assess HPV vaccination coverage, intention to HPV vaccination, cervical cancer knowledge, and HPV knowledge among female middle and high school students. | a. low. 10.2% b. 54.2% c. 62.2% e. cervical cancer knowledge: 58.6% | The subjects had moderate knowledge of cervical cancer and HPV. There were significant differences in cervical cancer knowledge scores between the intended group and the not-intended group for vaccination. | L: Cross-sectional study, data collection was conducted in specific areas | 80% |

| Han & Son (2021) [29] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 230 mothers of daughters of middle school (2nd grade) | To investigate environmental factors influencing mothers’ decision-making regarding vaccination of HPV for their daughters. | a. 75.7% (The rate of the daughters) b. 53.6% c. 9.79 out of 23 d. 21.27 out of 63 | The factors affecting HPV vaccination intention were attitudes toward HPV vaccination, information communicated by healthcare providers, and the provision of positive information regarding the HPV vaccination. | S: Proportional sampling considering the sizes of the metropolises and provinces L: Cross-sectional study, data collection was conducted in specific areas | 100% |

| Hong (2019) [30] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 249 mothers of daughters in elementary and middle school | To identify factors that influence HPV vaccination intention and behavior for mothers with a teenage daughter as the subject of HPV vaccine-free inoculation from 2016 based on the theory of planned behavior. | a. 41.8% (The rate of daughters) b. 18.84/14.63 (vaccinated/unvaccinated) out of 21 d. 18.89/15.34 out of 21 e. subjective norms: 17.76/14.55 out of 21, perceived behavior control: 25.06/21.88 out of 28 b, d, e: showed a significant difference between the subjects HPV vaccination status | The factors affecting the HPV vaccination intention were attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control in order. The factors influencing HPV vaccination behavior were level of education, subject’s vaccination status, recommendation of health care provider, vaccination status of surrounding people, intention, etc. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling, subjects mostly residing in rural areas | 100% |

| Hong & Chung (2019) [31] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 285 mothers of adolescent daughters (12–13 years) | To evaluate the accuracy of an HPV vaccination behavior model based on the health belief model. | a. high. 42.1% (The rate of daughters) b. high. 5.67 out of 7 e. vaccination-related health belief: perceived susceptibility: 2.04 out of 4, perceived seriousness: 2.90 out of 4, perceived benefit: 3.09 out of 4, perceived barrier: 2.09 out of 4 The vaccination rate was high due to the change in the perception of the parents and the introduction of the national vaccination program. Perceived benefits had effects on vaccination behavior by completely mediating the intention. | The vaccination intention was an important variable for predicting vaccination behaviors. Perceived benefits had effects on the vaccinating behavior by completely mediating the intention, while the perceived barriers had effects on the vaccinating behavior by partially mediating the intention. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling, subjects mostly residing in rural areas | 100% |

| Jang (2018) [23] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 246 male, n = 298 female students in high school | To identify and compare the factors associated with HPV vaccination intention between male and female high school students | a. 1.2%/16.4% (male/female): very low b. 47.6% (male)/86.2% (female) c. very low. 2.33 (male)/3.99 (F) out of 13~14 d. 3.07 (male)/3.31 (female) out of 5 e. vaccination-related health belief: 2.36/2.37 out of 4 | The factors affecting the HPV vaccination of male students were religion, sexual experience, safety concerns, perceived needs, the importance of prevention, and perceived susceptibility. The factors affecting the HPV vaccination of female students were awareness of HPV vaccination and the importance of prevention. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling, convenience sampling from a single site. | 60% |

| Kang & Lee (2021) [10] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 231 parents of sons in elementary school (5–6th grades) | To determine how attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) were related to parents’ intentions to vaccinate their sons in elementary school against HPV, applying the updated theory of planned behavior. | b. 13.87 out of 21 d. 15.46 out of 21 e. subjective norms: 11.45 out of 21, perceived behavior: 20.52 out of 28 * e directly predicted the b | The simple effect of attitude to intention was significant under three different levels of the PBC (low, moderate, and high), but the magnitudes of the relationships were not homogeneous. Subjective norms and PBC directly predicted the intention of HPV vaccination. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling | 100% |

| Kang & Moneyham (2011) [32] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 726 high school girls, n = 667 mothers | To examine the attitudes, intentions, and perceived barriers to HPV vaccination among Korean high school girls and their mothers. | a. 0.8% (the rate of high school girls) b. 3.32/3.43 (girl/mother) out of 5 d. favorable 2.98/2.98 (girl/mother) out of 5 | The major barriers to HPV vaccination were the high cost, the fact that not many people they knew had received the vaccination, and the HPV vaccination had not been personally recommended. | S: Samples were collected in various region L: Cross-sectional study | 100% |

| Kang (2011) [33] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 101 mothers of adolescent girls | To examine mothers’ knowledge about HPV vaccination to prevent cervical cancer in Korea. | a. 5.9% (the rate of the daughters) c. 24.2 out of 100 (low) * c of the vaccination group was significantly higher than that of the non-vaccinated group | The HPV vaccine knowledge score of the vaccination group was significantly higher than that of the non-vaccinated group. The reasons for not vaccinating their daughters against the HPV were the financial burden, the lack of HPV knowledge, and worries about possible side effects. | L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling from a single site. | 100% |

| Kim (2012) [34] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive design (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 757 health teachers of elementary, middle, high, and special schools | To assess HPV knowledge, compare the health beliefs toward HPV vaccination and intention to recommend HPV vaccination for girls and boys, and identify the factors influencing the intention to recommend HPV vaccination for girls and boys among Korean health teachers. | c. 7.71 out of 20 (low) b. 4.60/5.80 (boys/girls): Intention to recommend HPV vaccination e. HPV awareness: 76.4% There are differences in their intention to recommend HPV vaccine for girls and boys. | Factors related to the intention of vaccination for girls were the HPV vaccination status of the health teachers’ children, the teachers’ Pap-test experience, perceived benefits, susceptibility, and barriers. -Factors related to the intention to HPV vaccination for boys were the health teachers’ career duration, HPV knowledge, perceived benefits, susceptibility, and severity. | S: A highly representative sample was used, using a theoretical framework L: (1) Cross-sectional study, (2) Convenience sampling | 100% |

| Kim (2015) [27] | QT: Quasi-experimental study | n = 117 of students in elementary school (5th grade) | To determine the awareness among fifth-grade girls and boys of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), cancer, and HPV, and to determine the factors associated with intention to obtain the HPV vaccination. | b. 4.17/4.26 (boys/girls) out of 5 after education c. 4.58/4.95 (boys/girls) out of 8 after education * After education, there was no gender difference in b and c (no pre-test done) | There were significant gender differences with respect to responses to the statements “STD is preventable” and “cancer is preventable”, and concerns about the pain associated with vaccine injection. After HPV education, there were no significant gender differences in HPV knowledge and intention to obtain the HPV vaccination. | S: Experimental study design L: Lack of a control group, convenience sampling from a single site. | 60% |

| Kim & Choi (2017) [28] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 200 mothers of teenagers who were not vaccinated against HPV | To examine the intention of mothers to vaccinate their teenage children against HPV infection, according to the children’s sex. Based on the theory of planned behavior, the study identified the sex-specific predictors of mothers’ intention to vaccinate their teenage children against HPV. | b. 4.59/4.94 (boys/girls) d. 4.98/5.39 (boys/girls) e. subjective norms: 4.31/4.62, perceived behavior control: 5.31/5.31 * The differences between b, d, & e scores were not statistically significant between their children’s sex. | Among the mother with sons, the intention to vaccinate against HPV was significantly correlated with attitude, PBC, and subjective norms. Among the mothers with daughters, the intention to vaccinate against HPV also was significantly correlated with attitude, PBC, and subjective norms. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling from a single site. | 100% |

| Kim et al. (2019) [35] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 121 mothers of daughters in elementary school | To identify the impacts of HPV vaccination-related health beliefs, attitudes toward HPV vaccination, and subjective norms on HPV vaccination intent targeting mothers of elementary school daughters. | a. 11.6% (The rate of the daughters) b. 17.35 out of 21 d. 17.96 out of 21 e. vaccination-related health belief: 30.45 out of 44, Subjective norms: 16.26 out of 21 Attitudes toward HPV vaccination, subjective norms, vaccination plans for their children, and mother’s vaccination status were significant factors influencing HPV vaccination intention. These factors accounted for 72% of the HPV vaccination intention. | The factors affecting HPV vaccination intention were attitude toward HPV vaccination, subjective norms, vaccination plans for their children, and the mother’s vaccination status. The biggest influencing factor was HPV vaccination attitudes. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, data collection from a limited regional area | 100% |

| Lee et al. (2017) [12] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive design (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 140 mothers of daughters in elementary and middle schools (9~14 years old) | To assess the ranges of perceptions and personal experience and their influences on attitudes regarding HPV vaccinations of children among mothers of adolescent daughters. | b. 70% c. 48% The more the participants’ knowledge about HPV infection and about the relationship of HPV to cervical cancer, the more positive their attitudes. | The more the participants’ pre-knowledge about HPV infection and about the relationship of HPV to cervical cancer, the more positive their attitudes. As the level of education rose, the proportion of mothers with negative attitudes toward vaccinating their adolescent daughters rose as well. | S: The questionnaire was distributed randomly in three different schools L: Cross-section study, small sample size, and questionnaire were distributed in a well-developed city in Korea | 100% |

| Nam & Lee (2021) [24] | QT: Cross-sectional comparative design (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 171 mothers of daughters in elementary school (5–6th grade) | To provide basic data for the development of a nursing intervention program in order to improve the intention to receive HPV vaccination intention of mothers of daughters in elementary school by confirming the mediating effect of self-efficacy in the relationship between knowledge of HPV vaccine, attitude towards vaccination, subjective norm, and intention to receive a vaccination. | a. 15.2% (The rate of the daughters) b. high. 28.38 out of 35 c. average. 7.91 out of 16 d. high. 22.57 out of 28 e. subjective norms: high. 5.75 out of −12 to 12, self-efficacy: high. 16.65 out of 21 The fully mediating effect of self-efficacy was confirmed in the relationship between the knowledge of the HPV vaccine and the intention to receive a vaccination. | The fully mediating effect of self-efficacy in the relationship between the knowledge of the HPV vaccine and the intention of the vaccinations. The partial mediating effect of self-efficacy was confirmed in the relationship between attitude towards HPV vaccination and the intention of vaccination. The partial mediating effect of self-efficacy was confirmed in the relationship between the subjective norm for HPV vaccination and the intention to receive a vaccination. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, data collection from limited regional area | 60% |

| Oh & Lee (2018) [36] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 132 mothers of students in elementary school | To identify the factors associated with the intention of HPV vaccination among mothers of daughters in elementary school. | a. 5.3% (The rate of the daughters) b. 8.67 out of 21 c. 7.55 out of 16 d. 7.42 out of 21 e. subjective norms: 7.09 out of 21, perceived behavior control: 15.77 out of 35 The attitudes toward vaccination, perceived behavior and subjective norms were significant factors influencing HPV vaccination intention. | The factors affecting the predictor of vaccination were attitude toward HPV vaccination, perceived behavior control, and subjective norm as meaningful predictors. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, data collection from the limited regional area | 100% |

| Park & Kim (2020) [37] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 151 mothers of boys in elementary school (4–6th grade) | To identify the factors influencing mothers’ intention to vaccinate their elementary-school sons against HPV. | a. none. 0% (The rate of the sons) b. 5.04 out of 7 c. 11.13 out of 20 d. 5.25 out of 7 e. subjective norms: 4.47 out of 7, self-efficacy: 4.94 out of 7 Self-efficacy and subjective norms towards HPV vaccination were significant factors influencing mothers’ intention to vaccinate their elementary-school sons. | The factors that influenced the intention of vaccination are self-efficacy and subjective norms towards HPV vaccination. | S: Use a theoretical framework L: Cross-sectional study, data collection from a limited regional area, response bias by using a self-report questionnaire | 100% |

| Park & Jang (2017) [38] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 298 mothers of daughters in middle or high school | To identify the factors that influence the practices and the intentions of HPV vaccination among adolescent daughters’ mothers. | a. 13.1% (The rate of the daughters) b. 84.6% c. 5.8 out of 15 e. sex-related communication: 79.9%(sex), 72.8%(STD), 73.2%(contraception) The intention to receive HPV vaccination was mainly influenced by HPV knowledge. | The factors that influenced HPV vaccination most were their family history of cervical cancer, educational backgrounds, and awareness of the HPV vaccine. | L: Cross-sectional study, convenience sampling, data collection from the limited regional area | 100% |

| Yoo (2014) [39] | QT: Cross-sectional descriptive study (Self-reporting questionnaire) | n = 234 mothers of daughters in high school | To examine the knowledge level of HPV, cervical cancer, and vaccination status among Korean mothers of daughters in high school. | a. 3.9% (the rate of the daughters) low b. 85% (high) c. 4.21 out of 20 e. HPV knowledge: 3.88 out of 7 | The major barrier to HPV vaccination was the concern for side effects from the vaccination. The most effective recommendation for HPV vaccination came from healthcare providers. | L: Cross-sectional study, data collection from a limited regional area, the proportion of low-income and low-educated people among the subjects is relatively low | 100% |

| Study Number # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Choi & Park (2016) [25] | Choi & Cheon (2015) [26] | Han & Son (2017) [29] | Hong (2019) [30] | Hong & Chung (2019) [31] | Jang (2018) [23] | Kang & Lee (2021) [10] | Kang & Moneyham (2011) [32] | Kang (2011) [33] | Kim (2012) [34] | Kim (2015) [27] | Kim & Choi (2017) [28] | Kim et al. (2019) [35] | Lee et al. (2017) [12] | Nam & Lee (2021) [20] | Oh & Lee (2018) [36] | Park & Kim (2020) [37] | Park & Jang (2017) [38] | Yoo (2014) [39] |

| Q1. Qualitative Studies | |||||||||||||||||||

| Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Q3. Non-Randomized Studies | |||||||||||||||||||

| Are the participants representative of the target population? | N | ||||||||||||||||||

| Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | Y | ||||||||||||||||||

| Are there complete outcome data? | Y | ||||||||||||||||||

| Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | N | ||||||||||||||||||

| During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | Y | ||||||||||||||||||

| Q4. Quantitative Descriptive Studies | |||||||||||||||||||

| Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Is the sample representative of the target population? | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Are the measurements appropriate? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Q5. Mixed Methods Studies | |||||||||||||||||||

| Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | |||||||||||||||||||

| Quality Score | 80% | 80% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 60% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 60% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 60% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Selected Studies

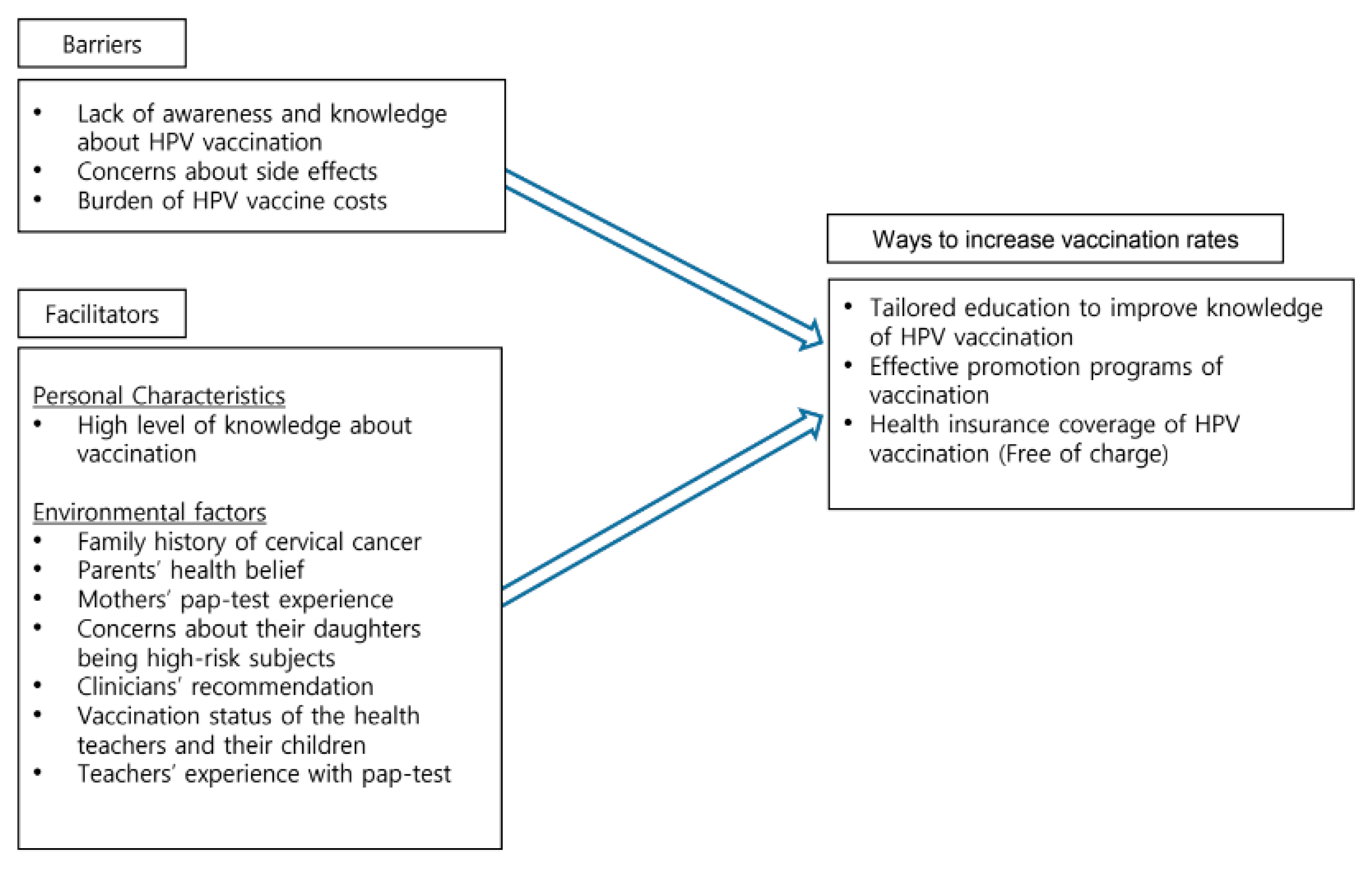

3.1.1. Facilitator

3.1.2. Barriers

3.1.3. Ways to Increase Vaccination Uptake

3.2. Critique of Selected Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge and Awareness

4.2. Family and Peer Influences

4.3. School Influences

4.4. Healthcare Providers’ Role

4.5. Policies and Costs

4.6. Recommendations for Improvement

Limitations

5. Implications

5.1. Family and Individual Approaches

5.2. Community Involvement

5.3. Health Professionals Roles

5.4. Policymakers

5.5. Actional Steps

6. Conclusions

Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chesson, H.W.; Dunne, E.F.; Hariri, S.; Markowitz, L.E. The Estimated Lifetime Probability of Acquiring Human Papillomavirus in the United States. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2014, 41, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, L.E.; Dunne, E.F.; Saraiya, M.; Chesson, H.W.; Curtis, C.R.; Gee, J.; Bocchini, J.A., Jr.; Unger, E.R. Human papillomavirus vaccination: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2014, 63, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Saura-Lázaro, A.; Montoliu, A.; Brotons, M.; Alemany, L.; Diallo, M.S.; Afsar, O.Z.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Mosina, L.; Contreras, M.; et al. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010–2019. Prev. Med. 2021, 144, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yu, J.H.; Kim, Y.M. Evaluation of the national child vaccination support project, 2014–2017. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2019, 12, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Kwon, B.-S.; Jeong, S.J.; Suh, D.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.B.; No, J.H. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in South Korea. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 49, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, C.; Yankey, D.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Markowitz, L.E.; Williams, C.L.; Fredua, B.; McNamara, L.A.; Stokley, S.; Singleton, J.A. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.-J.; Bae, S.; Kim, S. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Intent among Mothers of Adolescent Sons: A National Survey on HPV Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs in South Korea. World J. Men’s Health 2023, 41, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T.; Konta, T.; Sho, R.; Osaki, T.; Souri, M.; Suzuki, N.; Kayama, T.; Ueno, Y. Factors associated with health intentions and behaviour among health checkup participants in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.H.; Lee, E.-H. Updated Theory of Planned Behavior in predicting parents’ intentions to vaccinate their sons in elementary school against human papillomavirus. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs. 2021, 32, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, M.; Loux, T.; Shacham, E.; Tiro, J.A.; Arnold, L.D. Barriers to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among young adults, aged 18–35. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.N.; Chang, K.H.J.; Cho, S.S.; Park, S.H.; Park, S.T. Attitudes regarding HPV vaccinations of children among mothers with adolescent daughters in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kang, S.J. Factors influencing HPV Vaccination and Vaccination Intention among Korean adult women: A systematic review. J. Korean Public Health Nurs. 2018, 32, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, S.A.; Mullen, P.D.; Lopez, D.M.; Savas, L.S.; Fernández, M.E. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the US: A systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev. Med. 2020, 131, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhanes, D.; Yong, C.P.; Yap, Y.Y.; Saw, P.S.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Khan, T.M. Factors influencing intention to obtain the HPV vaccine in South East Asian and Western Pacific regions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, M.; Berg, C.J.; Escoffery, C.; Jang, H.M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Travis, L.; Bednarczyk, R.A. A systematic review of practice-, provider-, and patient-level determinants impacting Asian-Americans’ human papillomavirus vaccine intention and uptake. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6388–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wu, J.; Zheng, M. Barriers to and facilitators of human papillomavirus vaccination among people aged 9 to 26 years: A systematic review. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2021, 48, e255–e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pot, M.; van Keulen, H.M.; Ruiter, R.A.; Eekhout, I.; Mollema, L.; Paulussen, T.W. Motivational and contextual determinants of HPV-vaccination uptake: A longitudinal study among mothers of girls invited for the HPV-vaccination. Prev. Med. 2017, 100, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.K.; Lee, J.S.; Jeong, Y.J. Sport Consumption Behavior of Baby Boomers: Using MMAT for Systematic Review. Korean J. Sport Manag. 2020, 25, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Regist. Copyr. 2018, 10, 1148552. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, M.; Peterson, K.; Raina, P.; Chang, S.; Shekelle, P. Avoiding Bias in Selecting Studies. 20 February 2013. In Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, I. Comparison of factors associated with Intention to HPV vaccination between male and female high school students: Focusing on HPV knowledge, attitude and health beliefs related to HPV. J. Korean Soc. Sch. Health 2018, 31, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.A.; Lee, Y.E. Influencing factors on intention to receive human papillomavirus vaccination in mothers of elementary school girls: Focusing on the mediating effects of self-efficacy. J. Korean Soc. Matern. Child. Health 2021, 25, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Park, S. A study on the predictors of Korean male students’ intention to receive human papillomavirus vaccination. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 3354–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.-S.; Cheon, S. HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccination coverage and intention among female middle and high school students. J. Korean Soc. Living Environ. Syst. 2015, 22, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W. Awareness of human papillomavirus and factors associated with intention to obtain HPV vaccination among Korean youth: Quasi experimental study. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2015, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.M.; Choi, J.S. Mothers’ intentions to vaccinate their teenaged children against human papillomavirus, as predicted by sex in South Korea: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 14, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Son, H. Environmental factors affecting mothers’ decision-making about the HPV vaccination for their daughters. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4412–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H. Factors affecting the intentions and behavior of human papilloma virus vaccination in adolescent daughters. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2019, 19, 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.H.; Chung, Y.H. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination of female adolescent mothers. J. Digit. Converg. 2019, 17, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.S.; Moneyham, L. Attitudes, intentions, and perceived barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean high school girls and their mothers. Cancer Nurs. 2011, 34, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H. Mothers’ HPV-related knowledge in an area. J. Korean Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 11, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W. Knowledge about human papillomavirus (HPV), and health beliefs and intention to recommend HPV vaccination for girls and boys among Korean health teachers. Vaccine 2012, 30, 5327–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Sung, M.-H.; Kim, Y.A.; Park, H.-J. Factors influencing HPV vaccination intention in mothers with elementary school daughters. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2019, 25, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.J.; Lee, E.M. Convergence related factors and HPV vaccination intention for mothers with children elementary school. J. Digit. Converg. 2018, 16, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.Y.; Kim, T.I. Factors influencing mothers’ intention to vaccinate their elementary school sons against human papillomavirus. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2020, 26, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jang, I. Factors influencing practice and intention of HPV vaccination among adolescent daughter’s mothers: Focusing on HPV knowledge and sex-related communication. J. Korean Soc. Sch. Health 2017, 30, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, M.-S. Knowledge level of human papillomavirus, cervical cancer and vaccination status among mothers with daughters in high school. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2014, 20, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.R.; Kim, M.Y.; Chung, S.E. Methods and strategies utilized in published qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, A.S.; Madrigal, J.M.; Jordan, L.; Patel, A. Effectiveness of an educational intervention to increase human papillomavirus knowledge in high-risk minority women. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2018, 22, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, C.; Stoney, T.; Hutton, H.; Parrella, A.; Kang, M.; Macartney, K.; Leask, J.; McCaffery, K.; Zimet, G.; Brotherton, J.M.; et al. School-based HPV vaccination positively impacts parents’ attitudes toward adolescent vaccination. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4190–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, K.M.; Hinyard, L. Factors associated with HPV vaccination in young males. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.M.; Alqahtani, N.; Chang, S.; Cox, C. Knowledge, beliefs, and practice regarding human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among American college students: Application of the health belief model. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Sharma, M.; Lee, R.C. Designing and evaluating a health belief model-based intervention to increase intent of HPV vaccination among college males. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2014, 34, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, W.C.; Macintosh, J.L.; Vaughn, A.A.; Graff, T.C. Strength of belief: Religious commitment, knowledge, and HPV vaccination adherence. Psycho. Oncol. 2019, 28, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasymova, S. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccine knowledge, the intention to vaccinate, and HPV vaccination uptake among male college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolek, C.O.; Opanga, S.A.; Okalebo, F.; Birichi, A.; Kurdi, A.; Godman, B.; Meyer, J.C. Impact of parental knowledge and beliefs on HPV vaccine hesitancy in Kenya-findings and implications. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Lee, S.Y. Why do some Korean parents hesitate to vaccinate their children? Epidemiol. Health 2019, 41, e2019031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, E.; Donahue, K.; Sturm, L.; Champion, V.; Zimet, G. The association between maternal human papillomavirus (HPV) experiences and HPV vaccination of their children. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.Y.; Cheon, H.J. Acceptability for HPV vaccination in parent-child dyads in terms of regulatory focus, message framing and appeal. Korean J. Advert. 2015, 26, 25–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, A.F.; Delinger, R.L.; Eisenberg, M.C.; Campredon, L.P.; Walline, H.M.; Carey, T.E.; Meza, R. HPV vaccination has not increased sexual activity or accelerated sexual debut in a college-aged cohoroht of men and women. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Skinner, S.R.; Stoney, T.; Marshall, H.S.; Collins, J.; Jones, J.; Hutton, H.; Parrella, A.; Cooper, S.; McGeechan, K.; et al. Is it like one of those infectious kind of things? The importance of educating young people about HPV and HPV vaccination at school. Sex. Educ. 2017, 17, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquier, A.; Branchereau, M.; Gauchet, A.; Bonnay, S.; Simon, M.; Ecollan, M.; Chevreul, K.; Mueller, J.E.; Gagneux-Brunon, A.; Thilly, N.; et al. Promoting HPV vaccination at school: A mixed methods study exploring knowledge, beliefs and attitudes of French school staff. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.L.; Ashwood, D.; Richardson, G. BSchool nurses’ professional practice in the HPV vaccine decision making process. J. Sch. Nurs. 2015, 32, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Do, T.Q.N.; Hsu, E.; Schmeler, K.M.; Montealegre, J.R.; Rodriguez, A.M. School-based human papillomavirus vaccination program for increasing vaccine uptake in an underserved area in Texas. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 8, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, T.; Wilson, I.M.; Prue, G.; McLaughlin, M.; Hughes, C.M. Impact of school-based educational interventions in middle adolescent populations (15–17 yrs) on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination uptake and perceptions/knowledge of HPV and its associated cancers: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2020, 139, 106168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchio, S.; Bertoncello, C.; Baldovin, T.; Fonzo, M.; Bennici, S.E.; Buja, A.; Majori, S.; Baldo, V. Awareness of HPV and drivers of HPV vaccine uptake among university students: A quantitative, cross-sectional study. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1514–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, A.; Zecevic, A.; Diachun, L. Influenza Vaccinations: Older Adults’ Decision-Making Process. Can. J. Aging/Rev. Can. Vieil. 2014, 33, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.; Kim, J.H. Factors affecting influenza vaccination in adults aged 50–64 years with high-risk chronic diseases in South Korea. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Btoush, R.; Kohler, R.K.; Carmody, D.P.; Hudson, S.V.; Tsui, J. Factors that influence healthcare provider recommendation of HPV vaccination. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2022, 36, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, H.B.; Trotter, C.; Hickman, M.; Audrey, S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: A qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szilagyi, P.G.; Humiston, S.G.; Stephens-Shields, A.J.; Localio, R.; Breck, A.; Kelly, M.K.; Wright, M.; Grundmeier, R.W.; Albertin, C.; Shone, L.P.; et al. Effect of training pediatric clinicians in human papillomavirus communication strategies on human papillomavirus vaccination rates: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader, A.E.; Miller-Day, M.; Rey, R.T.; Selvan, P.; Pezalla, A.E.; Hecht, M.L. The impact of HPV vaccine narratives on social media: Testing narrative engagement theory with a diverse sample of young adults. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinka, K.; Kavanagh, K.; Gordon, R.; Love, J.; Potts, A.; Donaghy, M.; Robertson, C. Achieving high and equitable coverage of adolescent HPV vaccine in Scotland. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.; Audrey, S.; Mytton, J.A.; Hickman, M.; Trotter, C. Examining inequalities in the uptake of the school-based HPV vaccination programme in England: A retrospective cohort study. J. Public Health 2014, 36, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.; Chantler, T.; Finn, A.; Kesten, J.; Hickman, M.; Letley, L.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Thomas, C.; Worthington, K.; Yates, J.; et al. Development of an educational package for the universal human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programme: A co-production study with young people and key informants. Res. Involv. Engag. 2022, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expanding National Support for Human Papillomavirus Infection Vaccination 2022. 11 March 2022. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501010000&bid=0015&list_no=718935&cg_code=&act=view&nPage=1 (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Spencer, J.C.; Brewer, N.T.; Trogdon, J.G.; Weinberger, M.; Coyne-Beasley, T.; Wheeler, S.B. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to increase HPV vaccine uptake. Pediatrics 2020, 146, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; De Gagne, J.C.; Son, Y.D.; Chae, S.-M. Completeness of human papilloma virus vaccination: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 39, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthy People. Immunization and Infectious Diseases. 3 December 2022. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- World Health Organization. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Coverage. 2022. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/coverage/hpv.html?CODE=KOR&ANTIGEN=HPV_FEM&YEAR= (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, H.K. Effect of HPV prevention education on college students based on Planned Behavior Theory. J. Korean Oil Chem. Soc. 2021, 38, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, M.K.; Yang, S.J. Effects of Human Papillomavirus vaccination education on male college students. Korean Assoc. Learn. Curric. Instr. 2019, 19, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Fu, L.; Yang, Y.; An, R. Social media-assisted interventions on human papillomavirus and vaccination-related knowledge, intention and behavior: A scoping review. Health Educ. Res. 2022, 37, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, L.; Hansen, B.R.; Pandian, V. HPV immunization among young adults (HIYA!) in family practice: A quality im-provement project. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celentano, I.; Winer, R.L.; Jang, S.H.; Ibrahim, A.; Mohamed, F.B.; Lin, J.; Amsalu, F.; Ali, A.A.; Taylor, V.M.; Ko, L.K. Development of a theory-based HPV vaccine promotion comic book for East African adolescents in the US. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, H.; Choi, S.; Lee, J.-Y. An Integrative Review of the Influence on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Adherence among Adolescents. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182534

Shin H, Choi S, Lee J-Y. An Integrative Review of the Influence on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Adherence among Adolescents. Healthcare. 2023; 11(18):2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182534

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Hyewon, Sunyeob Choi, and Ju-Young Lee. 2023. "An Integrative Review of the Influence on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Adherence among Adolescents" Healthcare 11, no. 18: 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182534

APA StyleShin, H., Choi, S., & Lee, J.-Y. (2023). An Integrative Review of the Influence on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Adherence among Adolescents. Healthcare, 11(18), 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182534