Impact of Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Organisations Working with Underserved Communities with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in England

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Evaluation Design

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

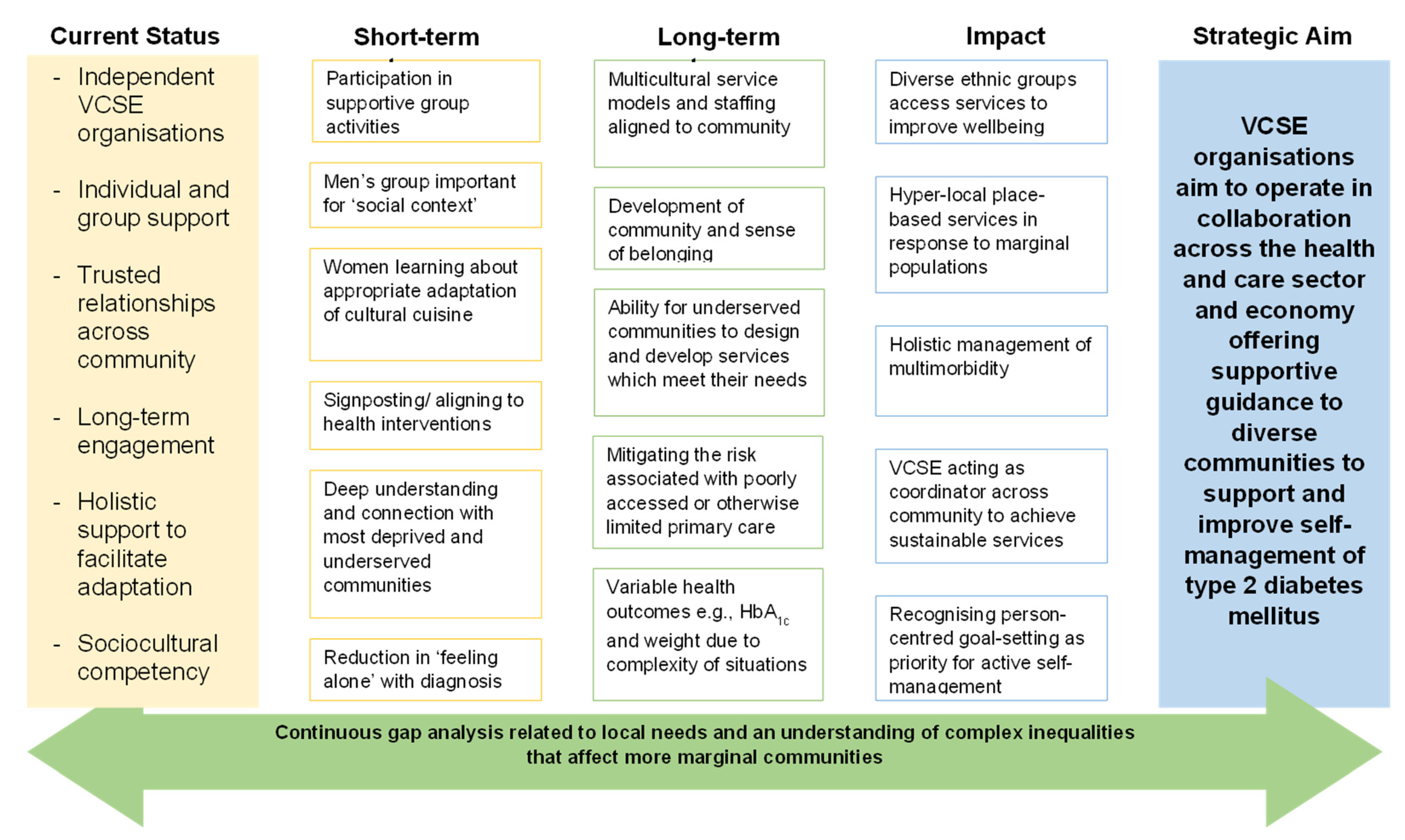

2.3. The Theory of Change

2.4. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

3.1. The Study Participants

3.2. Identified Themes

3.2.1. Individual and Group Support for Self-Management

“they told me to watch my diet, watch what I eat-plenty greens, fewer carbs, and to exercise, and that will keep my blood sugars down”.

“I was invited to some talks, but I didn’t go. I was overweight and struggled to walk, and nobody could take me in their car” (Asian British Male, 65+ years).

“I was signposted to DESMOND. The programme affirmed things I know. It was useful”

“…very disjointed, and it’s difficult to find out about that. I tended only to find out about things by chance, in some instances through desperation” (White British Male, 65+ years).

“My GP told me to lose weight and stop eating rice and chapati and other things. My sister also had diabetes a few years before, and she also told me some tips”.

“At present, I don’t get any [information]. I am just living with the original information I was given about diet and taking one tablet until today. It concerns me because I don’t know whether my blood sugar is gone” (White British Male, 65+ years).

“I think it has to be the internet, to be honest. Yeah. I found a lot on the internet about various foods and how they affect your blood sugars”.

“And it also happened that she [neighbour] had diabetes. And she says to me, “oh, there’s a group going on at [name of VCSE]”… And I felt renewed, elated because it was a group that, that there were other people with the same diagnosis, the same struggle”.

3.2.2. Trusted Services and Relationships across the Community

“Diabetic nurse.... Well, it’s just generally sent me for bloods, look at my feet. Quick chat. Jobs a good ‘un!” (Unknown).

“at the moment, due to the pandemic, no one [is supporting with diabetes management]; that’s what I feel let down by because I think if you’ve got something like diabetes, I should be getting support”.

“the information I was given was appropriate for me. I visited the nurse at the doctor’s surgery every 3 months for my bloods, she was very good, and I developed a good relationship with her. She told me about exercise classes in the area and also told me about health walks”.

“my mental health is really bad due to not managing diabetes. It has affected my life. I try to avoid my GP appointments because I know I struggle to manage my diabetes”.

“I get most of my information now from community hub, I go for the keep fit sessions, and they do some health information cafes where they talk about healthy things to eat and portion sizes. They also tell you what food to avoid if you have diabetes. It has been a good refresher for me”. (Pakistani Female, 65+ years).

3.2.3. Long-Term Engagement with Services

“I had a couple of things that I spoke to a doctor about: dehydration, night sweat, that kind of thing. And they did a blood test. So, it was a blood test that revealed. Like yeah, because yeah, my mom’s diabetic. And then I’ve always known it was coming. Yeah, it was just a case of, obviously, two brothers. And I was never sure if it was going to be me or them too. But it seems to have come down the female line” (White British Female, 56–64 years).

“the doctor sent me for blood tests, and they came back showing I had diabetes. I was so shocked and upset. I didn’t even know young people got diabetes”.

“I was very, very upset when I found out I had diabetes. I was scared that I would not be able to eat all the food that I loved and worried about what I would eat”.

“The first few years were very tough. I stopped eating out and I stopped visiting parties and friends because I was worried that they would offer me food and I wouldn’t be able to eat anything. I was also scared that people would be watching me and watching what I eat. This made me isolated and depressed, and I developed social anxiety. It has taken me years to get over this, and now I feel I am confident and in control”.

“I didn’t really take on board or understand how serious diabetes is. I thought if I take my tablets, watch my diet, and look after my feet, I’d be ok…. but talking to people, they tell me about problems with their kidneys and blood flow to their legs, lots of problems. I hope I don’t get any of this” (Black Caribbean British Female, 65+ years).

3.2.4. Sociocultural Context of Diet and Nutritional Choices

“My husband was very helpful and supportive...he helped me reduce some weight…I realised that when I cut down on sugary stuff and started eating less rice and chapati, my weight dropped by itself. I also started walking a lot, and me and my husband would go for walks after the evening meal.”

“Anyway, apparently, you’re not supposed to have carbohydrates and sugars, which is, like, most of what I eat, potatoes, bread”.

“I eat a lot of onions and green onions and leeks and that kind of thing…very particular triggers and learning how to regulate how much fruit I eat, shouldn’t eat too much fruit, certain fruits you should avoid, and so on. Yeah, I learned a lot from the internet”.

3.2.5. Multifaceted Adaptation to the Long-Term Condition

“The information I got was from …. a really good group. You know, it’s, it helps me really, to manage.. day -to-day menu, day-to--to-day exercising, everything. I mean, every…everyone that was there was going through the same thing. I mean, the shared experience, we all shared our experience, you know, because everybody was different there. And they understood what everybody else had going on. So, it helped”.

“I immediately started walking and eating more fruits and vegetables and lost a lot of weight. I controlled it via diet for at least 2 years. After 2 years, I was put on medication. I am still learning about things even at this stage. I have stopped eating all sugary stuff; I have a lot of self-control” (Pakistani Female, 65+ years).

“I also tried some bitter drinks that people in Pakistan drink when they have diabetes, that helps me keep my sugar level under control, and I also eat bitter gourds, that is a very bitter vegetable. I also put cinnamon in my tea as I have heard that it helps lower when levels are high. I am very careful I don’t let my levels go high”.

“So, there’s nowt [nothing] he’s going to do for me, says you…you’ve got diabetes, and you smoke. So anyway, so basically, I’m just left here with a perforated eardrum,” said a White British Male (56–64 years).

3.2.6. Shared Community Support Network

“There is a need for a lot of improvement culturally because then if we introduce…traditionally if there is one person gets the information, he spread it out to the [the rest of the community]… a big job to for the people’s awareness in mainly an Asian community”.

“we need to meet up regularly and consistently. Peer support and good communication” (Black British Caribbean Male, 56–64 years).

“A safe place, a comfortable place…. I’d like to make a place where anybody can come. You don’t have to talk about it if you just want to come to sit. Have a cup of coffee—a bit like the men’s group”.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Somerset County Council. Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Sector in Somerset; Somerset County Council: Taunton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Confederation. How Health and Care Systems Can Work Better with Vcse Partners; NHS Confederation: Cardiff, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England and NHS Improvement. Integrating Care Next Steps to Building Strong and Effective Integrated Care Systems across England. 2020 NHS England and NHS Improvement; NHS: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Management (Update); The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GOV.UK. Joint Review of Partnerships and Investment in Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise Organisations in the Health and Care Sector; GOV.UK: London, UK, 2016.

- Flanagan, S.M.; Hancock, B. Reaching the hard to reach—Lessons learned from the VCS (voluntary and community Sector). A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The King’s Fund. Tough Challenges but New Possibilities: Shaping the Post COVID-19 World with the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise Sector; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Martikke, S.; Moxham, C. Public Sector Commissioning: Experiences of Voluntary Organizations Delivering Health and Social Services. Int. J. Public Adm. 2010, 33, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehi, F.; Menon, A.; Bird, D. Diabetes Care in the Digital Era: A Synoptic Overview. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2018, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Captieux, M.; Pearce, G.; Parke, H.L.; Epiphaniou, E.; Wild, S.; Taylor, S.J.C.; Pinnock, H. Supported self-management for people with type 2 diabetes: A meta-review of quantitative systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e024262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjiconstantinou, M.; Eborall, H.; Troughton, J.; Robertson, N.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. A secondary qualitative analysis exploring the emotional and physical challenges of living with type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Diabetes 2021, 21, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sahouri, A.; Merrell, J.; Snelgrove, S. Barriers to good glycemic control levels and adherence to diabetes management plan in adults with Type-2 diabetes in Jordan: A literature review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogre, V.; Abanga, Z.O.; Tzelepis, F.; Johnson, N.A.; Paul, C. Psychometric evaluation of the summary of diabetes self-care activities measure in Ghanaian adults living with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 149, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catapan, S.d.C.; Nair, U.; Gray, L.; Calvo, M.; Bird, D.; Janda, M.; Fatehi, F.; Menon, A.; Russell, A. Same goals, different challenges: A systematic review of perspectives of people with diabetes and healthcare professionals on Type 2 diabetes care. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DESMOND. 2023. Available online: https://www.desmond.nhs.uk/modules-posts/newly-diagnosed-and-foundation (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Olson, J.L.; White, B.; Mitchell, H.; Halliday, J.; Skinner, T.; Schofield, D.; Sweeting, J.; Watson, N. The design of an evaluation framework for diabetes self-management education and support programs delivered nationally. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.M.; Davies, M.J.; Etherton-Beer, C.; McGough, S.; Schofield, D.; Jensen, J.F.; Watson, N. Increasing patient activation through diabetes self-management education: Outcomes of DESMOND in regional Western Australia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallosso, H.; Mandalia, P.; Gray, L.J.; Chudasama, Y.V.; Choudhury, S.; Taheri, S.; Patel, N.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. The effectiveness of a structured group education programme for people with established type 2 diabetes in a multi-ethnic population in primary care: A cluster randomised trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bury, M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol. Health Illn. 1982, 4, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörnsten, A.; Sandström, H.; Lundman, B. Personal understandings of illness among people with type 2 diabetes. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 47, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. The Impact of Primary Care: A Focused Review. Scientifica 2012, 2012, 432892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.K.; Hemmestad, L.; MacDonald, C.S.; Langberg, H.; Valentiner, L.S. Motivation and Barriers to Maintaining Lifestyle Changes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes after an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (The U-TURN Trial): A Longitudinal Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, K.M.V.; Kanaya, A.M. Why are South Asians prone to type 2 diabetes? A hypothesis based on underexplored pathways. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, R.; Gupta, P.K.; Mohan, V. Diabetes in South Asians: Phenotype, Clinical Presentation, and Natural History. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2018, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, U.P.; Pradeepa, R.; Weber, M.B.; Narayan, K.V.; Mohan, V. Type 2 diabetes in South Asians: Similarities and differences with white Caucasian and other populations. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1281, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, K.; Bower, P.; Burch, P.; Cotterill, S.; Sanders, C. On the borderline of diabetes: Understanding how individuals resist and reframe diabetes risk. Health Risk Soc. 2021, 23, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, E.; Waqar, M.; Sinclair, A.; Randhawa, G. Meeting the Challenge of Diabetes in Ageing and Diverse Populations: A Review of the Literature from the UK. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 8030627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, E.; Randhawa, G.; Farrington, K.; Greenwood, R.; Feehally, J.; Choi, P.; Lightstone, L. Lack of Awareness of Kidney Complications Despite Familiarity with Diabetes: A Multi-Ethnic Qualitative Study. J. Ren. Care 2011, 37, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, E.; Randhawa, G.; Singh, M. What’s the worry with diabetes? Learning from the experiences of white European and South Asian people with a new diagnosis of diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes 2014, 8, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotubo, O.A. A perspective on health inequalities in BAME communities and how to improve access to primary care. Future Health J. 2021, 8, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kings Fund. Strong Communities, Wellbeing and Resilience. 2023. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/improving-publics-health/strong-communities-wellbeing-and-resilience (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Mayne, J. Useful Theory of Change Models. Can. J. Program Eval. 2015, 30, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, C.H. Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families. In New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts; Connell, J., Ed.; Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, J. Theory of Change Analysis: Building Robust Theories of Change. Can. J. Program Eval. 2017, 32, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.T.; Preskill, H.; Catsambas, T.T. An overview of appreciative inquiry in evaluation. New Dir. Eval. 2003, 2003, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear-Smith, F.; Jackson, C.; Greenhalgh, T. Co-design and implementation research: Challenges and solutions for ethics committees. BMC Med. Ethic 2015, 16, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, D.D.; Trosten-Bloom, A. The Power of Appreciative Inquiry: A Practical Guide to Positive Change; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.L.; Cooperrider, D.L.; Srivastva, S. A Contemporary Commentary on Appreciative Inquiry in Organizational Life. In Organizational Generativity: The Appreciative Inquiry Summit and a Scholarship of Transformation; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; Volume 4, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Finegold, M.A.; Holland, B.M.; Lingham, T. Appreciative Inquiry and Public Dialogue: An Approach to Community Change. Public Organ. Rev. 2002, 2, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locock, L.; Boaz, A. Drawing straight lines along blurred boundaries: Qualitative research, patient and public involvement in medical research, co-production and co-design. Evid. Policy A J. Res. Debate Pract. 2019, 15, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otter.ai Inc. Otter.ai. 2022. Available online: https://methods.sagepub.com/case/innovation-in-transcribing-data-meet-otter-ai#i289 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Goldsmith, L. Using Framework Analysis in Applied Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 2061–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Firth, J.; Children, J.S.; Nursing, Y.P. Qualitative data analysis: The framework approach. Nurse Res. 2011, 18, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, E.; Lee, L.; De Silva, M.; Lund, C. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2015, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, S.; Franklin, M.; Haywood, A.; Stone, T.; Jones, M.; Mason, S.; Sterniczuk, K. Sharing real-world data for public benefit: A qualitative exploration of stakeholder views and perceptions. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funnell, S.C.; Rogers, P.J. Purposeful Program Theory Effective Use of Theories of Change and Logic Models; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission (CQC). My Diabetes, My Care. 2016. Available online: https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/themed-work/my-diabetes-my-care-community-diabetes-care-review (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Debussche, X.; Balcou-Debussche, M.; Ballet, D.; Caroupin-Soupoutevin, J. Health literacy in context: Struggling to self-manage diabetes—A longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e046759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain-Gambles, M.; Leese, B.; Atkin, K.; Brown, J.; Mason, S.; Tovey, P. Involving South Asian patients in clinical trials. Health Technol. Assess. 2004, 8, 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.P.; Kubisch, A.C. Applying a Theory of Change Approach to the Evaluation of Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Progress, Prospects, and Problems. New Approaches Eval. Community Initiat. 1998, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, D.; Slay, J.; Stephens, L.; Public Services Inside out. Putting Co-Production into Practice. New Economics Foundation and NESTA. 2010. Available online: https://neweconomics.org/2010/04/public-services-inside (accessed on 1 June 2023).

| Sex (Male/Female) (%) | 14/16 (47%/53%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (%) | 26–45 | 4 (13%) |

| 46–55 | 8 (27%) | |

| 56–65 | 5 (17%) | |

| 65+ | 9 (30%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (13%) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | Asian or Asian British | 4 (13%) |

| Black or Black British | 7 (23%) | |

| Mixed—Other | 3 (10%) | |

| White—British | 11 (37%) | |

| White—Other | 1 (3%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (13%) | |

| Education status (%) | No formal qualifications | 2 (7%) |

| Up to GCSE or equivalent | 5 (17%) | |

| AS/A level or equivalent | 2 (7%) | |

| Apprenticeship | 1 (3%) | |

| Further Education | 6 (20%) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 4 (13%) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 1 (3%) | |

| Prefer not to say/unanswered | 9 (30%) | |

| Time since diagnosis (years) (%) | 0–4.9 | 13 (43%) |

| 5–9.9 | 2 (7%) | |

| 10–14.9 | 5 (17%) | |

| 15–19.9 | 1 (3%) | |

| 20+ | 2 (7%) | |

| Prefer not to say/unanswered | 7 (23%) | |

| English Indices of Multiple Deprivation (2019) [by postcode data] (%) | 0–20% most deprived | 14 (47%) |

| 21–50% | 7 (23%) | |

| 51–80% | 1 (3%) | |

| 20% least deprived | 2 (7%) | |

| Prefer not to say/unanswered | 6 (20%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nield, L.; Bhanbhro, S.; Steers, H.; Young, A.; Fowler Davis, S. Impact of Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Organisations Working with Underserved Communities with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in England. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182499

Nield L, Bhanbhro S, Steers H, Young A, Fowler Davis S. Impact of Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Organisations Working with Underserved Communities with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in England. Healthcare. 2023; 11(18):2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182499

Chicago/Turabian StyleNield, Lucie, Sadiq Bhanbhro, Helen Steers, Anna Young, and Sally Fowler Davis. 2023. "Impact of Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Organisations Working with Underserved Communities with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in England" Healthcare 11, no. 18: 2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182499

APA StyleNield, L., Bhanbhro, S., Steers, H., Young, A., & Fowler Davis, S. (2023). Impact of Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) Organisations Working with Underserved Communities with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in England. Healthcare, 11(18), 2499. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182499