The Association between Physical Activity and Anxiety in Aging: A Comparative Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

2.5. Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

3.2. The Level of PA in Older People

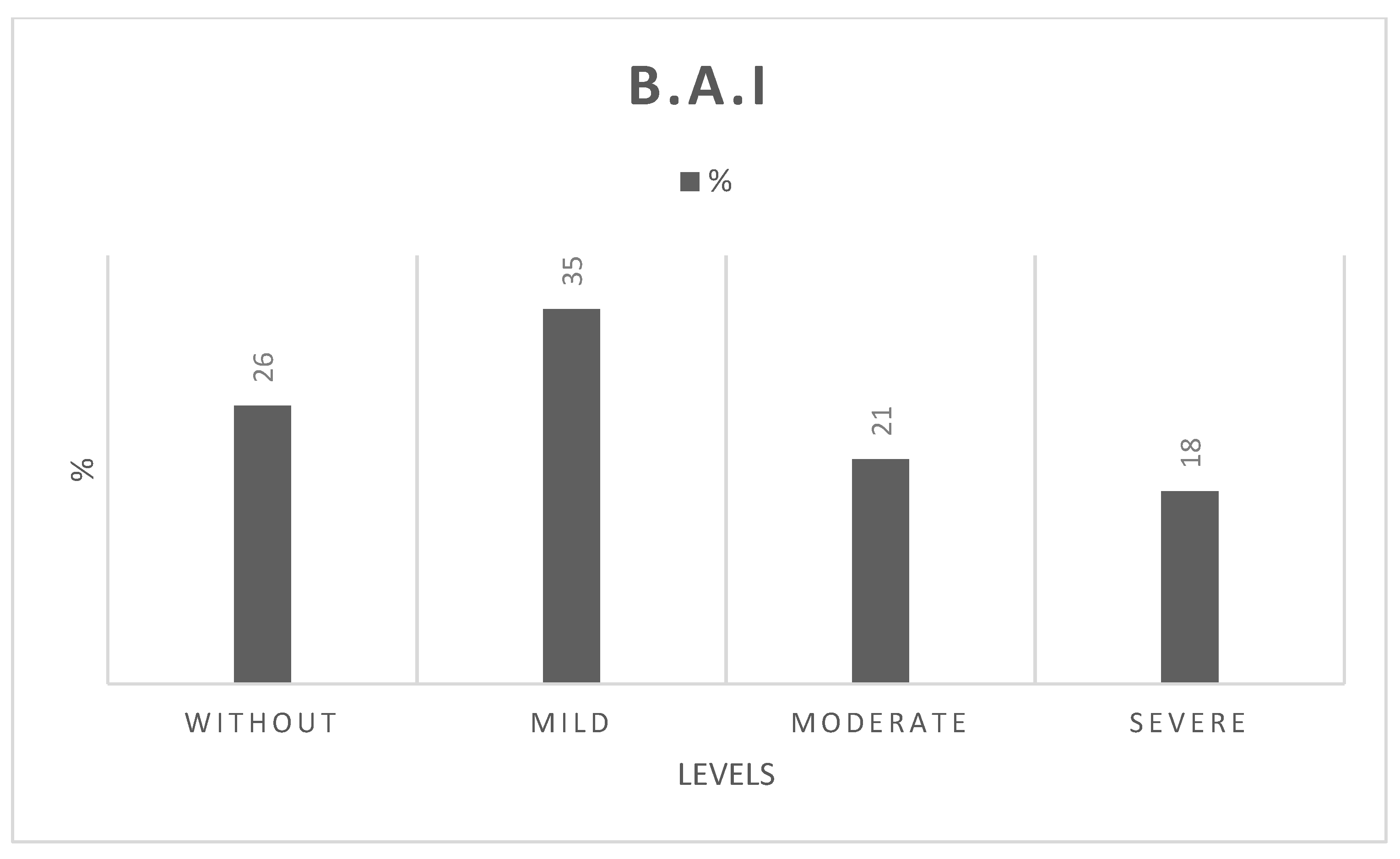

3.3. The Level of Anxiety in Older People

3.4. The Level of Anxiety in Older People

3.5. The Association between Anxiety and Education, Gender and Living Status

3.6. The Anxiety Levels According to the Age Groups

3.7. The Association between Anxiety and PA in Older People

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sempungu, J.K.; Choi, M.; Lee, E.H.; Lee, Y.H. The Trend of Healthcare Needs among Elders and Its Association with Healthcare Access and Quality in Low-Income Countries: An Exploration of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Comellas, A.; Valmaña, G.S.; Catalina, Q.M.; Baena, I.G.; Mendioroz Peña, J.; Roura Poch, P.; Sabata Carrera, A.; Cornet Pujol, I.; Casaldàliga Solà, À.; Fusté Gamisans, M.; et al. Effects of Physical Activity Interventions in the Elderly with Anxiety, Depression, and Low Social Support: A Clinical Multicentre Randomised Trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-L.; Chao, S.-R. The Effects of a Beauty Program on Self-Perception of Aging and Depression among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in an Agricultural Area in Taiwan. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B.; Michaelis, S.; Wedekind, D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 19, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsamo, M.; Cataldi, F.; Carlucci, L.; Fairfield, B. Assessment of anxiety in older adults: A review of self-report measures. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, C.; Mohlman, J.; Gum, A.; Stanley, M.; Beekman, A.T.; Wetherell, J.L.; Lenze, E.J. Anxiety disorders in older adults: Looking to DSM5 and beyond. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 872–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APA. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Alves, W.M.G.d.C.; Lima, T.A.; Alves, T.G.G.; Alves Filho, P.A.M.; Pimentel, C.P.; Sousa, E.C.; Cortinhas-Alves, E.A. The effect of resistance training on the anxiety symptoms and quality of life in elderly people with parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2018, 76, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Park, S.J. Immersive experience model of the elderly welfare centers supporting successful aging. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, F.A.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.; Crowe, M.J.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. Optimising care coordination strategies for physical activity referral scheme patients by Australian health professionals. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, H.A.; Figueira, O.A.; Corradi-Perini, C.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Figueira, A.A.; Lyra Da Silva, C.R.; Dantas, E.H.M. A Descriptive Analytical Study on Physical Activity and Quality of Life in Sustainable Aging A Descriptive Analytical Study on Physical Activity and Quality of Life in Sustainable Aging. Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, F.A.; Crowe, M.J.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. Physical activity promotion: A systematic review of the perceptions of healthcare professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netherway, J.; Smith, B.; Monforte, J. Training healthcare professionals on how to promote physical activity in the UK: A scoping review of current trends and future opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre-Roman, P.A.; Carmona-Torres, J.M.; Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A. Physical Activity, Ability to Walk, Weight Status, and Multimorbidity Levels in Older Spanish People: The National Health Survey (2009–2017). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setyanigsih, A.; Probosuseno, P.; Sofia, N.A. The Combination Effects of Physical Exercise and Dzikr for Anxiety Symptoms Improvement in the Elderly Hajj Pilgrim Candidates in Sragen. Acta Interna J. Intern. Med. 2020, 10, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, L.S.S.C.B.; Souza, E.C.; Rodrigues, R.A.S.; Fett, C.A.; Piva, A.B. The effects of physical activity on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in elderly people living in the community. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019, 41, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Lourido, D.; Prados, J.L.P.; Álvarez-Sousa, A. Ageing, Leisure Time Physical Activity and Health in Europe. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. BAI—An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmulski, M. Skeptical comment about double-blind trials. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2010, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šare, S.; Ljubičić, M.; Gusar, I.; Čanović, S.; Konjevoda, S. Self-esteem, anxiety, and depression in older people in nursing homes. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, S.V.; Mambrini, J.V.D.M.; Firmo, J.O.A.; Loyola Filho, A.I.D.; Souza Junior, P.R.B.D.; Andrade, F.B.D.; Lima-Costa, M.F. Prática de atividade física entre adultos mais velhos: Resultados do ELSI-Brasil. Rev. Saude Publica 2018, 52, 5s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitune, M.P.D.A.; Barros, M.B.D.A.; César, C.L.G.; Carandina, L.; Goldbaum, M.; Alves, M.C.G.P. Fatores associados à prática de atividade física global e de lazer em idosos: Inquérito de Saúde no Estado de São Paulo (ISA-SP), Brasil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2010, 26, 1606–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE Praticas de Esporte e Atividade Fisica—2015; IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017.

- Simarmata, V.P.A.; Achmad, L.N. The Analysis of Adult Female Anxiety in Facing the Future. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2022, 12, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreescu, C.; Lee, S. Anxiety disorders in the elderly. In Anxiety Disorders: Rethinking and Understanding Recent Discoveries; AEMB: Ruston, LA, USA, 2020; pp. 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell-Roesch, J.; Syrjanen, J.A.; Machulda, M.M.; Christianson, T.J.; Kremers, W.K.; Mielke, M.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Vassilaki, M.; Geda, Y.E. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and the outcome of cognitive trajectories in older adults free of dementia: The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zueck-Enríquez, M.D.C.; Soto, M.; Aguirre, S.I.; Ornelas, M.; Blanco, H.; Peinado, J.E.; Aguirre, J.F. Evidence of Validity and Reliability of the Lasher and Faulkender Anxiety about Aging Scale in Mexican Older Adults. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.Y.; Kim, E. Factors Influencing the Control of Hypertension According to the Gender of Older Adults. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Abella, J.; Mundó, J.; Haro, J.M.; Rubio-Valera, M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitarafan, L.; Kazemi, M.; Afrashte, M.Y. Relationship between styles of attachment to God and death anxiety resilience in the elderly. Iran. J. Ageing 2018, 12, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, A.; Sadeghmoghadam, L.; Shareinia, H.; Jahani, S.; Amiri, F. Investigating the role of perception of aging and associated factors in death anxiety among the elderly. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Luo, Y.; Chang, H.; Zhang, R.; Liu, R.; Jiang, Y.; Xi, H. The mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation in BIS/BAS sensitivities, depression, and anxiety among community-dwelling older adults in China. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.J.; Merwin, R.M. The role of exercise in management of mental health disorders: An integrative review. Annu. Rev. Med. 2021, 72, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaki, S.; Khesali, Z.; Farajzadeh, M.; Dalvand, S.; Moslemi, B.; Ghanei Gheshlagh, R. The relationship of depression and death anxiety to the quality of life among the elderly population. J. Hayat 2017, 23, 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Babazadeh, T.; Sarkhoshi, R.; Bahadori, F.; Moradi, F.; Shariat, F.; Sherizadeh, Y. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress disorders in elderly people residing in Khoy, Iran (2014–2015). J. Anal. Res. Clin. Med. 2016, 4, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkov, M.; Eminović, F.; Radovanović, S.; Dopsaj, M.; Pavlović, D.; Kljajić, D. Quality of life and depression in elderly persons engaged in physical activities. Vojn. Pregl. 2018, 75, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions | Answers | Percent | Absolute |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Feminine | 73.6 | 509 |

| Masculine | 26.2 | 181 | |

| Other | 0.1 | 1.0 | |

| Age-Bracket | 60–64 | 39.4 | 273 |

| 65–69 | 32.9 | 228 | |

| 70–74 | 18.3 | 127 | |

| 75–79 | 6.1 | 43 | |

| 80–84 | 2 | 14 | |

| 85–80 | 0.7 | 5 | |

| 90- | 0.6 | 4 | |

| Living Status | Family | 68.5 | 474 |

| Alone | 24.7 | 171 | |

| Friends | 0.7 | 5 | |

| Others | 6.1 | 42 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 10.6 | 73 |

| Married/Stable Union | 54.4 | 376 | |

| Separated/Divorced | 22.8 | 158 | |

| Widow | 12 | 83 | |

| Schooling | Iliterate | 0 | 0 |

| E.S. Incomplete | 2.6 | 18 | |

| E.S. Complete | 1.4 | 10 | |

| H.S. Incomplete | 1.9 | 13 | |

| H.S. Complete | 9.2 | 64 | |

| U.E. Incomplete | 9.2 | 64 | |

| U.E. Complete | 38.4 | 266 | |

| Pos-Graduation | 37 | 257 |

| BAI | Irritated | Relax | Afraid | Palpitation | Nervous | Suffocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 23.5% | 40% | 30.4% | 50.4% | 33.5% | 60.3% |

| Slightly | 43.6% | 38.5% | 39.3% | 34.4% | 44.4% | 27.3% |

| Moderately | 31.3% | 21.0% | 28.6% | 13.8% | 20.5% | 10.5% |

| Seriously | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.7% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.9% |

| Sociodemographic | Characteristic | Anxiety Level | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Yes | 3.26 ± 1.54 | |

| No | 5.14 ± 2.01 | ||

| <0.001 | |||

| Gender | Male | 4.9 ± 2.11 | |

| Female | 3.84 ± 2.1 | ||

| =0.02 | |||

| Level of education | Below University | 5.17 ± 1.85 | |

| University and up | 3.26 ± 1.4 | ||

| =0.027 | |||

| Living status | Family | 3.14 ± 1.3 | |

| Others | 5.2 ± 1.9 | ||

| =0.037 | |||

| Sample Anxiety | Absolute | 4.6 ± 2.8 | |

| Sample Anxiety % | Percentile | 25.5 ± 15.5 |

| Age | Mean | sd | min | max | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–64 | 1.31 | 1.06 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 271 |

| 65–69 | 1.25 | 1.06 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 227 |

| 70–74 | 1.30 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 127 |

| 75–79 | 1.29 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 42 |

| 80–84 | 1.29 | 1.14 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 14 |

| 85–89 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 5 |

| 90- | 1.75 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 4 |

| BAI | % Active | % Sedent |

|---|---|---|

| No | 35.36% | 29.29% |

| Mild | 27.99% | 20.20% |

| Moderate | 19.34% | 27.27% |

| Severe | 17.31% | 23.24% |

| Ind. Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | df | p-Value | Adj. OR | 95% CI (OR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| PA | −0.649 | 0.222 | 8.517 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.522 | 0.338 | 0.808 |

| Age 60–64 | 0.068 | 1.030 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.947 | 1.071 | 0.142 | 8.064 |

| Age 65–69 | −0.194 | 1.031 | 0.035 | 1 | 0.851 | 0.824 | 0.109 | 6.214 |

| Age 70–74 | −0.205 | 1.039 | 0.039 | 1 | 0.844 | 0.815 | 0.106 | 6.247 |

| Age 75–79 | −0.046 | 1.074 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.966 | 0.955 | 0.116 | 7.843 |

| Age 80–84 | −0.219 | 1.172 | 0.035 | 1 | 0.852 | 0.803 | 0.081 | 7.992 |

| Age 85- | −1.255 | 1.545 | 0.660 | 1 | 0.417 | 0.285 | 0.014 | 5.890 |

| Gender (1) | −0.353 | 0.197 | 3.198 | 1 | 0.074 | 0.703 | 0.477 | 1.035 |

| Living Status (1) | 0.306 | 0.398 | 0.591 | 1 | 0.442 | 1.358 | 0.623 | 2.960 |

| Living Status (2) | 0.235 | 0.353 | 0.442 | 1 | 0.506 | 1.265 | 0.633 | 2.528 |

| Living Status (3) | 0.802 | 0.987 | 0.659 | 1 | 0.417 | 2.229 | 0.322 | 15.439 |

| MaritalStatus (1) | 0.567 | 0.350 | 2.616 | 1 | 0.106 | 1.762 | 0.887 | 3.502 |

| MaritalStatus (2) | 0.379 | 0.304 | 1.547 | 1 | 0.214 | 1.460 | 0.804 | 2.652 |

| MaritalStatus (3) | 0.572 | 0.405 | 1.997 | 1 | 0.158 | 1.772 | 0.801 | 3.916 |

| MaritalStatus (4) | −0.095 | 0.319 | 0.089 | 1 | 0.765 | 0.909 | 0.486 | 1.699 |

| Schooling (1) | 0.604 | 0.388 | 2.431 | 1 | 0.119 | 1.830 | 0.856 | 3.911 |

| Schooling (2) | 0.403 | 0.335 | 1.449 | 1 | 0.229 | 1.497 | 0.776 | 2.885 |

| Schooling (3) | 0.247 | 0.240 | 1.066 | 1 | 0.302 | 1.281 | 0.801 | 2.048 |

| Schooling (4) | −0.283 | 0.279 | 1.029 | 1 | 0.310 | 0.754 | 0.437 | 1.301 |

| Constant | −0.440 | 1.142 | 0.148 | 1 | 0.700 | 0.644 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dantas, E.H.M.; Figueira, O.A.; Figueira, A.A.; Höekelmann, A.; Vale, R.G.d.S.; Figueira, J.A.; Figueira, H.A. The Association between Physical Activity and Anxiety in Aging: A Comparative Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152164

Dantas EHM, Figueira OA, Figueira AA, Höekelmann A, Vale RGdS, Figueira JA, Figueira HA. The Association between Physical Activity and Anxiety in Aging: A Comparative Analysis. Healthcare. 2023; 11(15):2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152164

Chicago/Turabian StyleDantas, Estelio Henrique Martin, Olivia Andrade Figueira, Alan Andrade Figueira, Anita Höekelmann, Rodrigo Gomes de Souza Vale, Joana Andrade Figueira, and Helena Andrade Figueira. 2023. "The Association between Physical Activity and Anxiety in Aging: A Comparative Analysis" Healthcare 11, no. 15: 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152164

APA StyleDantas, E. H. M., Figueira, O. A., Figueira, A. A., Höekelmann, A., Vale, R. G. d. S., Figueira, J. A., & Figueira, H. A. (2023). The Association between Physical Activity and Anxiety in Aging: A Comparative Analysis. Healthcare, 11(15), 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152164

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)