1. Introduction

As the non-contact society expands due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a new concept of health literacy is becoming essential in the current medical system for the correct dissemination of information on digital health [

1]. In the current global COVID-19 crisis, the development of vaccines and treatments is still in progress, and maintaining social distance remains one of the most effective solutions to containing the pandemic [

2]. This underscores the role and importance of interventions based on digital health technology. In the information age, personal health management has become easier due to the availability of internet-based health information using digital devices to enable self-diagnosis [

3]. As the amount of health information provided online increases, the internet will increasingly become an essential source of health information [

4,

5]. In the United States, approximately six out of ten adults search for health information online [

3].

In Korea, as older adults’ internet use increases due to the general accessibility of the mobile internet environment [

6], the need to manage and prevent chronic diseases in older adults by using a health management program based on mobile technology is becoming more critical. Korea is currently expanding mobile healthcare services through public health centers to provide information on lifestyle improvement, chronic disease prevention, and management services to more chronic disease risk groups [

7]. The increase in the use of information and communication technologies in health-related fields not only provides opportunities to improve and promote health but also raises additional concerns about solving new problems.

Health literacy refers to how individuals acquire, process, understand, and communicate health information and is known to be correlated with individuals’ health statuses [

8]. As the production and distribution of information rapidly expand and their impacts on life increase, low levels of health literacy can negatively affect not only individual health behaviors but also health management [

9]; moreover, the lower people’s levels of health literacy, the more negatively they perceive their health statuses [

10] and the higher the associated medical expenses due to more frequent hospital visits [

11,

12]. In particular, e-health literacy can be a factor that reflects an individual’s ability to understand and interpret health-related data on the internet, and as a result, it can help individuals achieve better health outcomes [

13].

A survey which comprehensively measured the availability of internet access, PC and mobile device usage, and internet utilization as they relate to the digital information gap in Korea has shown that the digital literacy level for four vulnerable groups (disabled people, low-income groups, farmers and fishermen, and older adults) was 72.7% compared to the general population. Although it had improved by 2.8% compared to the previous year (69.9%), the digital literacy level of older adults was 68.6% compared to the general public [

14]. In other words, the low levels of digital literacy for older adults may cause problems in their ability to obtain and understand health information, which may negatively affect their health. In particular, as Korea’s population ages and as most chronic disease patterns of older adults require continuous management, it is essential to discuss alternatives in the pursuit of internet health information for the maintenance of the health and treatment of diseases in older adults.

Health literacy is strongly correlated with socioeconomic factors such as level of education [

15,

16]. If we look at the literature on older adults’ ability to access internet health information and their internet health comprehension, much of the existing research has focused on the concept, definition, and relevance of health literacy [

17]. These studies were conducted on an individual level and on the level of organizations, communities, and healthcare systems [

18]. Research on the socioeconomically vulnerable is conducted continuously so that the gap in health literacy does not lead to health inequality; however, gender differences relating to internet health information are not sufficiently discussed [

19].

Since it is necessary to understand individual users’ points of view regarding the diffusion of new technologies [

20], it is necessary to pay attention to users’ technology acceptance prior to their behavior patterns in terms of technology use. A technology acceptance attitude refers to an individual’s positive or negative attitude toward a specific technology [

21]. Technology-use anxiety [

22] can negatively impact the use of technology and attitudes toward technology acceptance when targeting older adults [

22,

23,

24]. If the problem of technology-use anxiety among older adults is not addressed, discriminatory results may appear in public health due to older adults’ technology use and skill gaps. Therefore, it is necessary to study ways to alleviate the harmful effects of technology-use anxiety among older adults concerning new technologies.

It is also important to understand the degree of e-health literacy and anxiety related to technology use among older Koreans by gender and to participate in mobile and internet health interventions because the prevalence of chronic diseases is increasing. In addition, the digital information gap is increasing, despite the increase in the use of digital devices; moreover, the intention to manage health using digital devices is also increasing. From this perspective, an analysis of older adults’ smart device capacities can be used as primary data to help them manage their health using digital technology. Research findings indicate a gender disparity in digital literacy, with women facing more challenges and exhibiting lower levels of confidence in using technology compared to men [

25]. Hence, interventions to enhance digital literacy among older adults should prioritize addressing these gender differences. Additionally, while existing studies have generally reported lower levels of digital literacy among older individuals with lower levels of education and lower incomes, as well among those of advanced age, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a widespread impact on the older adult population, regardless of their socio-economic backgrounds [

26]. Consequently, as society transitions to a rapidly evolving non-face-to-face environment, all older adults, irrespective of their geographical locations, education levels, or incomes, have experienced a sense of powerlessness [

27]. This situation emphasizes the urgent need to achieve universal digital welfare. Furthermore, investigating the digital skills of older adults who are relatively privileged and educated could provide insights into providing digital welfare services to older adults in general. Notably, the differences in digital literacy observed among highly educated older adult groups can serve as compelling evidence to support the necessity of universal digital welfare in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study differs from previous studies in that it supplements other empirical studies by focusing on the characteristics of older adults. In addition, analyzing the degree of e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety by gender will make it possible to tailor education policies related to internet health information education based on the characteristics of older adults.

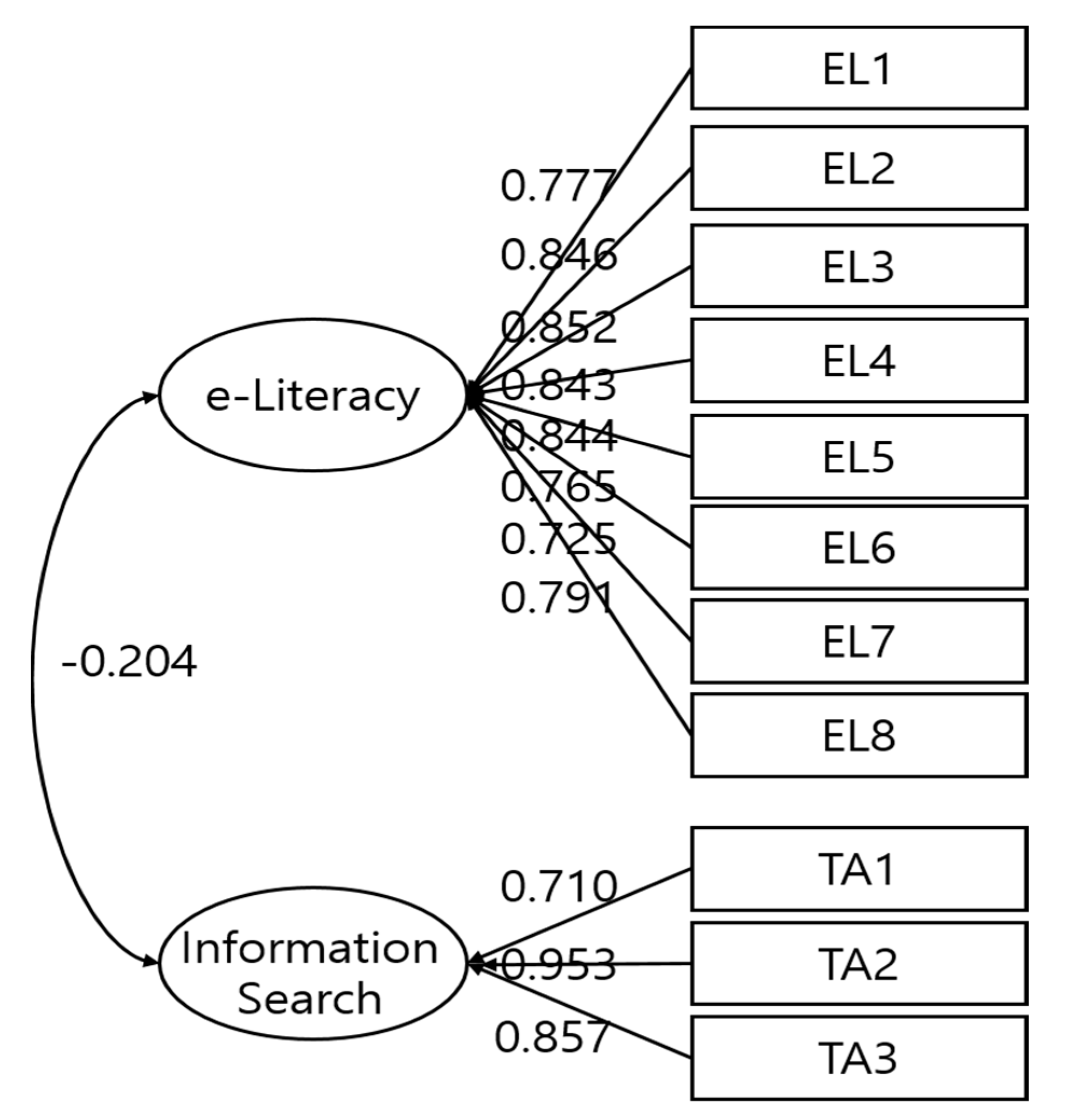

This study first verified the construct equivalence (i.e., form identity, measurement identity, and intercept identity) through a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis of the smart device acceptance capacity scale for older adults in Korea, and then it examined whether this study could commonly apply the acceptance capacity scale. Secondly, a latent mean analysis was used to verify potential gender differences between older adults in Korea for two factors (e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety) in terms of their smart device acceptance capacities. Consequently, the below research questions were proposed.

First, how is the construct equivalence (i.e., form, measurement, and intercept equivalence) verified according to the smart device capacity scale for older Korean adults?

Second, what are the potential differences in smart device acceptance capacities (e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety) based on the gender of older adults in Korea?

4. Discussion

This study conducted a latent mean analysis of e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety in older Korean men and women. To establish whether e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety are similar across the genders in older adults living in Korea, we conducted a hierarchical analysis of the morphological identity, measurement identity, and intercept identity. The results confirmed that e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety were common among older Korean men and women, and that the observed differences in the means reflected the actual differences between the groups for the latent factors. Until now, the

t-test and analysis of variance—the usual methods for comparing mean differences between groups—have had decisive weaknesses in that they do not take into account measurement errors [

40,

41]. The latent mean analysis method provides a more valid study result because it tests the mean difference using a latent variable with a controlled measurement error, and this suggests that the procedure used in this study was appropriate.

The latent mean analysis of e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety in this study showed a statistically significant difference between the genders only for technology-use anxiety. In addition, the potential average for the men was slightly higher. Based on Cohen’s effect size, e-health literacy showed a medium effectiveness of 0.67 and technology-use anxiety was at a level of 1.15.

The latent mean analysis has certain limitations, as it is a methodology that can only be executed when the assumptions of configuration invariance, metric invariance, and scalar invariance are met through multi-group confirmatory factor analysis. A limitation of the latent model is that it can solely accommodate MTMM (multitrait-multimethod) data if the indicators are completely homogeneous. This means that all indicators within each method have entirely correlated true score variables, which vary solely in scaling, implying they may have different intercepts and loadings [

39]. Furthermore, if the latent model presumes that the correlation structure is homogeneous across the methods for a given construct, it may not fit the data accurately. To overcome these challenges, Eid [

40] proposed a solution that involves incorporating indicator-specific residual factors for all indicators except for a reference one.

Previous studies have generally divided the factors influencing e-health literacy into personal, situational, and environmental factors [

42], and they have shown that demographic and sociological characteristics also have an influence [

43]. Studies conducted in Europe and Taiwan have found that men report lower levels of health literacy than women [

44,

45]. The higher the social status, education level, and economic level, the higher the found level of e-health literacy [

46,

47,

48]. This study found no statistically significant difference in e-health literacy between men and women, indicating that gender does not directly affect e-health literacy, as previous studies have suggested. In addition, there was a slight difference compared to the results of previous studies in that the men had a higher understanding of internet health information than the women when looking at the average values. Older adults, referred to as the baby-boomer generation in Korea, represent a generation that is economically, socially, and politically dominant, and they are an economically stable age group. In particular, the patriarchal concept, which is characteristic of this generation, is based on men’s economic superiority. The results of previous studies that showed a correlation between economic status and internet health information comprehension were partially supported by the results of this study.

In general, physiological and psychological functions change as aging progresses. This change also affects technology-use anxiety and appears as a heterogeneous response among older adults, in particular [

21], because user perception of the helpfulness and user-friendliness of technology can be regarded as an essential factor in using technology [

49]. A study that analyzed differences in mobile health app use found that gender was not associated with general use, but women were more likely to use nutrition, self-care, and reproductive health apps [

50]. In other words, while is difficult to conclude that there is a specific difference in the use of internet health information according to gender, there are some differences in the type of health information obtained. As for technology acceptance anxiety, this study’s finding that men experience more significant anxiety indirectly supports the results of previous studies that showed that older men (66 years and older) were less health literate than women [

51]. Sun and Zhang [

52] found that men’s acceptance or intention to use technology was more positive because men were more likely than women to engage in new technology or device used as a means to achieve a specific goal. Their finding differs from the results of this study, but a careful interpretation is required because the age groups of the subjects differed. However, it is necessary to consider the possibility of various interpretations and to understand the differences in the results of smart device capacity according to gender in terms of environmental context.

According to Lawton and Nahemow [

53], humans experience the aging process while adapting to a changing environmental context; moreover, the aging experience depends on context [

54]. In other words, even if an older adult feels anxious about using new technologies on a personal level, if an environment that compensates for such anxiety is provided, the negative effect of technology-use anxiety will decrease. Technology-use anxiety will be reduced by an older adult’s acceptance of technology. Therefore, for older adults who are reluctant to use smart device technology, the e-health literacy strategy should be adjusted based on their educational and digital literacy levels [

45].

This study has a number of limitations. First, this study’s questionnaire data were collected through an online survey. The possibility that older adults who were relatively accustomed to using computers and the internet would have participated in the survey cannot be excluded. In addition, considering the descriptive statistics of the study’s participants, it is highly likely that they represented older adults, and their education and income levels tended to be relatively higher than any other age group in Korea. In addition, this study assumed that older adults are a homogeneous group. In addition, this study only focused on e-health literacy, technology-use anxiety, and demographic characteristics as factors in smart device capacity.

Unlike earlier studies, this study focused on analyzing the differences between e-health literacy and technology acceptance anxiety. By using gender, which is a demographic characteristic, as a representative variable, and by analyzing gender characteristics in greater depth, future studies could provide information that could help to identify characteristics related to e-health literacy and technology acceptance anxiety in greater detail.

The results of this study showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the smart device capacity between older men and women living in Korea. However, there was a significant difference that depended on intentions and behavioral characteristics. The significant differences between men and women regarding the technology acceptance anxiety related to smart devices may cause a health gap in the future. It is, therefore, necessary to identify and remove obstacles that may affect the use of smart devices based on gender characteristics and to lower psychological anxiety about technology acceptance.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted an analysis of construct equivalence and latent mean according to gender in a smart device capacity scale for older adults living in Korea. The below conclusions were obtained.

First, as a result of a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis of the smart device acceptance capacity scale of older adults living in Korea, the construct equivalence was verified because the morphological equivalence, measurement equivalence, and intercept equivalence were all satisfied. It was possible to compare the differences in the latent factors by group as each latent variable and measurement variable for the men and women were equally applied to e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety.

Second, as a result of the latent mean analysis, the average difference between the groups regarding technology-use anxiety as a factor in smart device acceptance capacity was statistically significant, and the latent average for men was higher than that for women. When looking at the effect size of the potential mean difference, e-health literacy was 0.67 and technology-use anxiety was 1.15, showing a medium and a large effect size, respectively, based on the criteria suggested by Cohen. In follow-up research, it will be necessary to continuously check and revise the validity of the various variables that affect the acceptance of smart devices and develop and apply a new factor structure based on the results.

Lastly, one limitation of this study was the potential bias in the sample used for the research. The study included respondents who were adults over 50 years of age that used welfare centers, public health centers, senior citizen centers, and exercise centers in Seoul and Incheon, which may not be representative of the broader population of older adult individuals in Korea. Furthermore, the sample may have been biased towards those who were digitally literate and comfortable using technology, potentially limiting the generalizability of the study’s findings to a broader population of older adult individuals who may not be as technologically proficient. While the study’s findings provided valuable insights into the potential differences in e-health literacy and technology-use anxiety between men and women, it is essential to recognize the limitations of the sample used and interpret the study’s results with caution. Future research could adopt more inclusive sampling methods to ensure that the perspectives of a more diverse group of older adult individuals are represented.