Exploring Care Needs of Partners of Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals in Co-Transition: A Qualitative Interview Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Co-Transition

1.2. Professional Care for Partners

1.3. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

- The interviews were reviewed twice after transcription in order to become familiar with the data. The transcription itself also increased the understanding of the content of the interviews.

- The data were coded, with the initial codes matching the raw data as closely as possible. In total, approximately four coding rounds were conducted. Throughout this process, codes were expanded, split into multiple codes or merged together. The relevance of the codes was based on the formulated research questions.

- Recurring or similar codes across the interviews were grouped into coherent and meaningful themes, underpinned by a key analytic point. The possible relationships between these themes were analysed, creating a distinction between the main themes and subthemes.

- The initial themes were analysed once more and refined. Efforts were made to achieve good internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity. The aim was to make the data within themes sufficiently coherent and the data from different themes clearly distinguishable.

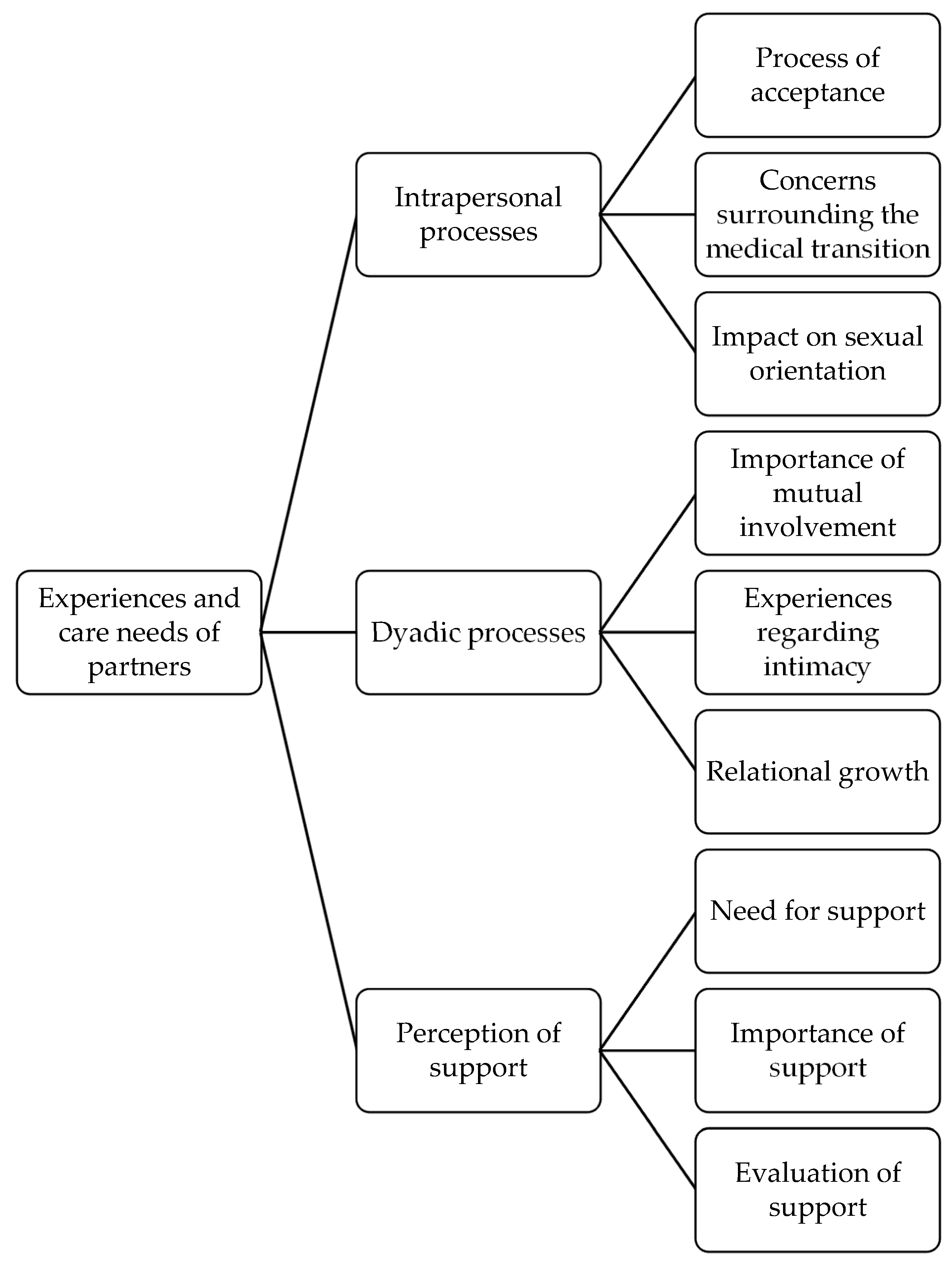

- The themes were defined and named. A graphical overview of the relationships between the themes found was created in the form of a thematic map.

- The themes found were selected and reported. This can be found in the Section 3.

2.5. Quality Control

3. Results

3.1. Intrapersonal Processes

3.1.1. Process of Acceptance

“I knew that from the beginning. So actually, I knew for over 10 years that he wanted to make the transition one day. We talked about it before we got into a relationship. I said at the time, “You have to do what you want to do. It’s your body, if you’re not comfortable with it, you have to do it. For me you don’t have to refrain from it, I will support you””.(Kathleen, 41 years old, woman, pansexual)

“It was a huge shock because I think there was still a part of me that thought, “It’ll never actually happen”, but in the end it did. I remember my first thought was that we would separate. That went through my head for a while, that I thought it wasn’t going to work”.(Emma, 21 years old, woman, pansexual)

“Things were going so well, everything felt so good, I didn’t understand what the issue was. I really tried to push it away in the beginning. […] We tried to talk a lot, but then there was a lot of crying, panic attacks, not being able to breathe,… It never came to a proper conversation. There were many attempts, but it didn’t work. I couldn’t cross that mental barrier”.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

“That’s when I broke down for the first time, because that’s when I realised my old partner was gone. “My previous partner is gone and now it’s Kevin. I have to get used to the fact that I will never get her back.” Whereas as a partner you know you’re not actually losing your partner”.(Kathleen, 41 years old, woman, pansexual)

3.1.2. Concerns Surrounding the Medical Transition

“Then I started thinking about what would change and came to the conclusion that only his eyes would stay the same. His voice will lower, he will get more body hair, his face will change. He will change in every respect. Then I thought, “But then I’ll be together with a completely different person””.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

“The most difficult thing was the facial surgery. I went to drop Lotte off, and when they came to get her to go to the operating room, I walked with her to the lift. There the nurse said: “This is as far as you can go, madam.” It was at that moment that I realised that this was the last time I would see her. I hadn’t thought about it that way before, but it hit me very hard at that moment”.(Eline, 41 years old, woman, not 100% heterosexual)

“The first time the operation had to be repeated, I really broke down at his bedside. I had to stay strong for him, but the moment I had to leave the hospital I think I cried for the first time. […] That was the first time and then there were more complications. After the fourth or fifth complication, where he had to have another surgery, I completely collapsed. I could not function anymore. I couldn’t do anything at all”.(Kathleen, 41 years old, woman, pansexual)

“But now his eggs are gone too, which means that my chances of having a child with Simon are just… gone. There’s no way I can have a child between the two of us. I find it very difficult that we can’t have genetic children of our own”.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

3.1.3. Impact on Sexual Orientation

“I also had a really hard time because I started questioning myself again. Many questions ran through my head, such as “If I stay with him, does that mean something about my own sexuality? Should I revise that? For me it was all clear before, should I let that go now?” And especially: “Should I go and figure this out once more and will I land on a different sexual orientation? And what if I don’t land on something else?””.(Kim, 34 years old, non-binary, lesbian)

“I actually find Dylan more attractive now than before, which I never expected… That’s something he was also very afraid of, but actually the truth is that I like him more every day as he becomes more like his true self. Everything falls into place now. I never expected that”.(Emma, 21 years old, woman, pansexual)

“I’m still mainly attracted to men. When I look around on the street, I still look at men and not at women, so I think that has remained the same”.(Sarah, 47 years old, woman, pansexual)

“I am not bisexual. I have a relationship with my partner. I love my partner and I cannot live without my partner. My partner is everything to me. She is a person I can say anything to without any difficulty. I have a relationship with this person”.(Célia, 51 years old, woman, heterosexual)

“I have to defend myself because now everyone expects me to be straight since I am with a man. It’s so hard because I feel like a part of my identity is no longer allowed because I chose to be with Simon”.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

3.2. Dyadic Processes

3.2.1. The Importance of Mutual Commitment

“If someone was troubled by something, if certain things were going to change or certain steps were going to be taken, we always had many conversations about that. We really always talked a lot about everything. And if you can tell your partner how you’re feeling, it’s really only half as hard”.(Sarah, 47 years old, woman, pansexual)

“Sometimes I felt I wasn’t being listened to. I understood that he had certain feelings and that something needed to happen, but I was also caught up in the story and I had feelings about it too, but that was not important. Of course, it’s not nice that I was crying about what he was going to undertake, but that’s how I felt. I felt like my feelings came second”.(Kim, 34 years old, non-binary, lesbian)

“Then I said to her, “Look, let’s go shopping and see what I think is appropriate for you to wear in the outside world.” That meant going into the men’s collection to look for more feminine pieces. A floral shirt, a first handbag that was still masculine, a first woman’s shoe…”.(Ruth, 56 years old, woman, bisexual)

3.2.2. Experiences Regarding Intimacy

“On a physical level, we still walk hand in hand in the streets and when we greet each other, it is with a peck on the lips. So, there is definitely still physical contact. Cuddling on the sofa and all that”.(Eline, 41 years old, woman, not 100% heterosexual)

“It’s trial and error. Everything from square one. You have to find out what he likes, what he doesn’t like, what we like together… But that shows the positive side of a relationship: that you can figure that out together”.(Kathleen, 41 years old, woman, pansexual)

“It was always difficult, right from the start. I knew that his body was something very difficult, so in the beginning it was mostly one-way traffic, but I was always understanding. Then the surgeries happened and it was better for a while. I felt we had a better connection, because his body was more in line with his true self. But now, in the past year, it is really difficult. There is no one-way traffic anymore. That’s a challenge”.(Emma, 21 years old, woman, pansexual)

3.2.3. Relational Growth

“It’s mainly made us even closer and more intimate with each other. Because what you share during a transition is so special that it just makes the bond stronger and more special”.(Sarah, 47 years old, woman, pansexual)

“I said two years ago, “I don’t want hormones. I don’t want breasts. You can dress like a man and have short hair and wear men’s underwear.” I felt that was far enough. But when I look at where we are now, I am happy with the steps we have taken. It is a struggle for me, but there is also a lot of reward. He really is a completely different person, he is so happy. […] It has also brought a lot of good things and we stand very strong in our relationship”.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

3.3. Perception of Support

3.3.1. Need for Support

“I struggled with it for a year. My parents didn’t know, so I couldn’t say to my parents, “I want to see a psychologist. Pay for the psychologist.”, because they would want to know why. I couldn’t talk about it, I couldn’t put it into words, so it was difficult”.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

“I know this will be a very difficult time. […] I’ve been to a psychologist previously for a long time and could talk to her about this topic quite well. I think I’ll need to start up therapy again before the phalloplasty. I know myself. I’m not going to wait too long, because I just know that I’m going to need to talk to someone about it”.(Emma, 21 years old, woman, pansexual)

3.3.2. The Importance of Support

“I dare not say that I would be sitting here now if I didn’t have the network I had or if I didn’t know how to find a therapist myself”.(Eline, 41 years old, woman, not 100% heterosexual)

“The fact that I could talk about it helped. The fact that I could say, “Look, this is hard” or “That’s not hard”. With a lot of other people you cannot share these things. […] With my therapist I had the space to say that it’s not easy”.(Ruth, 56 years old, woman, bisexual)

“I do believe that it has made it easier because you know that you are surrounded by all these people who support you. It really makes a big difference”.(Emma, 21 years old, woman, pansexual)

“It helped that there was someone who moderated between us and noticed certain things. We can talk well, but sometimes the actual message of what we’re saying doesn’t come across right away. […] On that level it was helpful. I think we still take the things we learned in therapy with us now. We know that there are things we think about differently and sometimes we have to accept that. What we weren’t so good at before, we are better at now”.(Kim, 34 years old, non-binary, lesbian)

“What I always find most important about the support group is that there is always someone who is in a more difficult situation and there is always someone who has a positive feeling, and that puts things into perspective. You need something to lift you up and you need to know that it’s not all that bad”.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

3.3.3. Evaluation of Support

“If you haven’t been through it, you don’t know what you’re talking about. That’s the big problem. […] A transition is such a unique experience that you actually have to be part of the process to know what it’s like”.(Kathleen, 41 years old, woman, pansexual)

“I think the support is there, but you have to go and find it yourself and take the necessary steps yourself. Especially in the beginning. Before we got support, we were at least seven to eight months along, whereas the first eight months is when you really need the help. We had already done a lot of the process ourselves”.(Kim, 34 years old, non-binary, lesbian)

“I think these evenings help a lot, but they are too infrequent and too far away. If you can’t make it yourself or there aren’t enough people, you have to wait six months. Especially now, because they’re adjusting the way they operate, there hasn’t been a meeting for a long time. I really need one”.(Lien, 23 years old, woman, lesbian)

4. Discussion

4.1. Experiences of Partners of TGD Individuals

4.2. Care Needs of Partners of TGD Individuals

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Study Strengths

4.5. Study Limitations

4.6. Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Topic | Item | Page Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | |||

| S1 | Title | Concise description of the nature and topic of the study identifying the study as qualitative or indicating the approach (e.g., ethnography, grounded theory) or data collection methods (e.g., interview, focus group) is recommended | 1 |

| S2 | Abstract | Summary of the key elements of the study using the abstract format of the intended publication; typically includes background, purpose, methods, results and conclusions | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| S3 | Problem formulation | Description and significance of the problem/phenomenon studied: review of relevant theory and empirical work; problem statement | 1–4 |

| S4 | Purpose of research question | Purpose of the study and specific objectives or questions | 4 |

| Methods | |||

| S5 | Qualitative approach and research paradigm | Qualitative approach (e.g., ethnography, grounded theory, case study, phenomenology, narrative research) and guiding theory if appropriate; identifying the research paradigm (e.g., postpositivist, constructivist/interpretivist) is also recommended; rationale 2 | 4–6 |

| S6 | Researcher characteristics and reflexivity | Researcher “characteristics that may influence the research, including personal attributes, qualifications/experience, relationship with participants, assumptions and/or presuppositions; potential or actual interaction between researcher” characteristics and the research questions, approach, methods, results and/or transferability | 6–7 |

| S7 | Context | Setting/site and salient contextual factors; rationale 2 | 4–6 |

| S8 | Sampling strategy | How and why research participants, documents, or events were selected; criteria for deciding when no further sampling was necessary (e.g., sampling saturation); rationale 2 | 4–5 |

| S9 | Ethical issues pertaining to human subjects | Documentation of approval by an appropriate ethics review board and participant consent, or explanation for lack thereof; other confidentiality and data security issues | 4 |

| S10 | Data collection methods | Types of data collected; details of data collection procedures including (as appropriate) start and stop dates of data collection and analysis, iterative process, triangulation of sources/methods, and modification of procedures in response to evolving study findings; rationale 2 | 5 |

| S11 | Data collection instruments and technologies | Description of instruments (e.g., interview guides, questionnaires) and devices (e.g., audio recorders) used for data collection; if/how the instruments(s) changed over the course of the study | 5 |

| S12 | Units of study | Number and relevant characteristics of participants, documents, or events included in the study; level of participation (could be reported in results) | 4–6 |

| S13 | Data processing | Methods for processing data prior to and during analysis, including transcription, data entry, data management and security, verification of data integrity, data coding, and anonymisation/deidentification of excerpts | 5–6 |

| S14 | Data analysis | Process by which inferences, themes, etc. were identified and developed, including the researchers involved in data analysis; usually references a specific paradigm or approach; rationale 2 | 5–6 |

| S15 | Techniques to enhance trustworthiness | Techniques to enhance trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis (e.g., member checking, audit trail, triangulation); rationale 2 | 6–7 |

| Results/findings | |||

| S16 | Syntheses and interpretation | Main findings (e.g., interpretations, inferences, and themes); might include development of a theory or model, or integration with prior research or theory | 7–17 |

| S17 | Links to empirical data | Evidence (e.g., quotes, field notes, text excerpts, photographs) to substantiate analytic findings | n/a (see “Data availability statement”) |

| Discussion | |||

| S18 | Integration with prior work, implications, transferability and contribution(s) to the field | Short summary of main findings; explanation of how findings and conclusions connect to, support, elaborate on, or challenge conclusions of earlier scholarship; discussion of scope of application/generalizability; identification of unique contributions(s) to scholarship in a discipline or field | 18–21 |

| S19 | Limitations | Trustworthiness and limitations of findings | 21 |

| Other | |||

| S20 | Conflicts of interest | Potential sources of influence of perceived influence on study conduct and conclusions; how these were managed | 22 |

| S21 | Funding | Sources of funding and other support; role of funders in data collection, interpretation and reporting | 22 |

Appendix B

Interview Guide

- Can you tell me a little about yourself?

- Where are you from?

- How would you describe your ethnicity?

- How old are you?

- What is your current relationship status and duration?

- How do you identify in terms of gender?

- How do you identify in terms of sexual orientation?

- Can you tell me a little about your partner?

- How does your partner identify in terms of gender?

- In what ways has your partner made gender-affirming changes?

- Has this had an effect on you?

- Has this affected your relationship?

- How did you deal with this?

- When and how did your partner disclose to you how they felt regarding their gender identity?

- What was your reaction?

- How did this make you feel? Did this feeling change over time?

- Has it affected you and/or your relationship? If so, in what way?

- How have you dealt with this?

- Can you tell me a little more about your relationship with your partner?

- How did you meet your partner?

- How long have you been together?

- What are the strengths of your relationship?

- What are the obstacles in your relationship?

- What are your experiences regarding emotional, physical and sexual intimacy?

- How do you view the future of your relationship?

- How have people around you reacted to your relationship with your partner?

- Your family

- Friends

- School and/or work

- Strangers, in public

- How did this make you feel? How did you experience this?

- How did these different reactions of others affect you and your perception of the relationship?

- Are these experiences different from experiences in previous relationships?

- Have you been sufficiently involved in the gender-affirming transition?

- In what way have you been involved?

- Were there any particular moments or events that were challenging for you?

- What were your needs at the time?

- How did you deal with it?

- What was and wasn’t helpful to you?

- What role did support from others (friends, general practitioner, psychologist, etc.) play?

- What kind of support would have been helpful for you?

- Is there anything you would have liked to have gone differently?

- Is there anything you’d still like to add?

References

- Brown, N.R. The sexual relationships of sexual-minority women partnered with trans men: A qualitative study. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2009, 39, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierckx, M.; Mortelmans, D.; Motmans, J. Role ambiguity and role conflict among partners of trans people. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 40, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckx, M.; Meier, P.; Motmans, J. “Beyond the box”: A comprehensive study of sexist, homophobic, and transphobic attitudes among the Belgian population. DiGeSt J. Divers. Gend. Stud. 2017, 4, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Being Trans in the European Union: Comparative Analysis of EU LGBT Survey Data. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2014-being-trans-eu-comparative-0_en.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Bethea, M.S.; McCollum, E.E. The disclosure experiences of male-to-female transgender individuals: A systems theory perspective. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2013, 12, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, G.; Stone, C.; Mustafa, M.M.; Wampuszyc, T.J. Couple relationships of transgender individuals and their partners: A 2017 update. Mich. Fam. Rev. 2016, 20, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweileh, W.M. Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature in transgender health (1900–2017). BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2018, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, L.F.; Bolland, K.S. Relationship partners of transgender individuals: A qualitative exploration. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2018, 35, 1251–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, C.T. Trans-kin undoing and redoing gender: Negotiating relational identity among friends and family of transgender persons. Sociol. Perspect. 2013, 56, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarel, K.E.; Reisner, S.L.; Laurenceau, J.P.; Nemoto, T.; Operario, D. Gender minority stress, mental health, and relationship quality: A dyadic investigation of transgender women and their cisgender male partners. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.C.; Sharp, C.; Michonski, J.; Babcock, J.C.; Fitzgerald, K. Romantic relationships of female-to-male trans men: A descriptive study. Int. J. Transgend. 2013, 14, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson-Schroth, L. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource for the Transgender Community; Oxford: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-1993-2537-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dierckx, M.; Motmans, J.; Mortelmans, D.; T’Sjoen, G. Families in transition: A literature review. Int. Rev. Psychiatr. 2016, 28, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, T.N.; Karney, B.R. Intimate Relationships; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-393-66721-9. [Google Scholar]

- Theron, L.; Collier, K.L. Experiences of female partners of masculine-identifying trans persons. Cult. Health Sex 2013, 15, S62–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgwal, A.; Van Wiele, J.; Motmans, J. Genoeg, Enough, Assez: Onderzoek Naar de Ervaringen Met Geweld van LGBTI-Personen in Vlaanderen [Enough: A Study on LGBTI People’s Experiences of Violence in Flanders]. Available online: https://www.transgenderinfo.be/sites/default/files/2023-03/Rapport%20Genoeg_Enough_Assez_2023.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Scheim, A.I.; Bauer, G.R. Sex and gender diversity among transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. J. Sex. Res. 2015, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaut, E.; Caen, M.; Dewaele, A.; Van Houdenhove, E. Seksuele gezondheid in Vlaanderen [Sexual health in Flanders]. In Seksuele Gezondheid in Vlaanderen [Sexual Health in Flanders]; Buysse, A., Caen, M., Dewaele, A., Enzlin, P., Lievens, J., T’Sjoen, G., Van Houtte, M., Vermeersch, H., Eds.; Academia Press: Ghent, Belgium, 2013; pp. 41–118. ISBN 978-9-0382-2079-6. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, H. The Transsexual Phenomenon; Symposium Publishing: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, P.J.; Kenna, J.C.; Brandon, S. Partnership in transsexualism. Part I. Paired and nonpaired groups. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1981, 10, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, B.; Bernstein, S.M. Female-to-male transsexuals and their partners. Can. J. Psychiatr. 1981, 26, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, K.A.; Riggs, D.W. Intimate relationship strengths and challenges amongst a sample of transgender people living in the United States. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2019, 36, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenning, E.; Buist, C.L. Social, psychological and economic challenges faced by transgender individuals and their significant others: Gaining insight through personal narratives. Cult. Health Sex 2013, 15, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, A.I. Transgender Emergence: Therapeutic Guidelines for Working with Gender-Variant People and Their Families; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, S.; Rosenfeld, C. Stages of adjustment in family members of transgender individuals. J. Fam. Psychother. 1996, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Bartle-Haring, S.; Day, R.D.; Gangamma, R. Couple communication, emotional and sexual intimacy, and relationship satisfaction. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2014, 40, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motmans, J.; T’Sjoen, G.; Meier, P. Geweldervaringen van Transgender Personen in België [Experiences of Violence of Transgender People in Belgium]. Available online: https://assets.vlaanderen.be/image/upload/v1646130728/Geweldervaringen_van_trans_personen_in_Belgie_-_dec_2014_lqgxc5.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.M.; Meyer, I.H. Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance [journal pre-proof]. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 101579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Nolle, K.; Marx, R.; Katz, M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. J. Homosex 2006, 51, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, M.L.; Testa, R.J. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012, 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Wethington, E. The contagion of stress across multiple roles. J. Marriage Fam. 1989, 51, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, A.K.; Bodenmann, G. The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.H.; Ellis, S.J.; Schmidt, J.M.; Byrne, J.L.; Veale, J.F. Mental health inequities among transgender people in Aotearoa New Zealand: Findings from the Counting Ourselves survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.; Radix, A.E.; Bouman, W.P.; Brown, G.R.; de Vries, A.L.C.; Deutsch, M.B.; Ettner, R.; Fraser, L.; Goodman, M.; Green, J.; et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int. J. Transgend. Health 2022, 23, S1–S259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giammattei, S.V. Beyond the binary: Trans-negotiations in couple and family therapy. Fam. Process. 2015, 54, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpas, J. From otherness to alliance: Transgender couples in therapy. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2006, 2, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samons, S.L. Can this marriage be saved? Addressing male-to-female transgender issues in couples therapy. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2009, 24, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, B.D. Therapeutic considerations in working with the family, friends, and partners of transgendered individuals. Fam. J. 2006, 14, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.; Murphy, M.J.; Bigner, J.J.; Wetchler, J.L. Handbook of LGBTQ-Affirmative Couple and Family Therapy, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-3672-2387-8. [Google Scholar]

- Transgender Infopunt. Waar Kan ik Terecht? [Where Can I Find Help?]. Available online: https://www.transgenderinfo.be/nl/familie/ex-partners/waar-kan-ik-terecht (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Smith, J.A. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4462-9846-6. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7619-2998-7. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Software and qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 803–820. ISBN 0-7619-1512-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, D.G. Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing trustworthiness of naturalistic enquiries. Educ. Commun. Technol. J. 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S. Emerging criteria for quality in qualitative and interpretive research. Qual. Inq. 1995, 1, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-8039-2431-4. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, H.M. Qualitative generalization, not the population but to the phenomenon: Reconceptualizing variation in qualitative research. Qual. Psychol. 2021, 8, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewins, F. Explaining stable partnerships among FTMs and MTFs: A significant difference? J. Sociol. 2002, 38, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pseudonym | Age | Nationality | Gender- Identity | Gender- Identity Partner | Sexual Orientation | Relationship Duration | Informed of TGD Identity Partner before Start Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emma | 21 | Belgian | woman | trans man | pansexual | 4 years | no |

| Ruth | 56 | Belgian | woman | woman | bisexual | 27 years | no |

| Sarah | 47 | Belgian | woman | trans woman | pansexual | 7 years | partially |

| Eline | 41 | Belgian | woman | woman | not 100% heterosexual | 10 years | no |

| Célia | 51 | Portuguese | woman | woman | heterosexual | 20 years | no |

| Emilie | 31 | Belgian | woman | trans man | pansexual | 8 years | yes |

| Lien | 23 | Belgian | woman | man | lesbian | 9 years | no |

| Kim | 34 | Belgian | non-binary | non-binary trans man | lesbian | 11 years | no |

| Kathleen | 41 | Belgian | woman | trans man | pansexual | 4 years | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Acker, I.; Dewaele, A.; Elaut, E.; Baetens, K. Exploring Care Needs of Partners of Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals in Co-Transition: A Qualitative Interview Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11111535

Van Acker I, Dewaele A, Elaut E, Baetens K. Exploring Care Needs of Partners of Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals in Co-Transition: A Qualitative Interview Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(11):1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11111535

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Acker, Isabeau, Alexis Dewaele, Els Elaut, and Kariann Baetens. 2023. "Exploring Care Needs of Partners of Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals in Co-Transition: A Qualitative Interview Study" Healthcare 11, no. 11: 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11111535

APA StyleVan Acker, I., Dewaele, A., Elaut, E., & Baetens, K. (2023). Exploring Care Needs of Partners of Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals in Co-Transition: A Qualitative Interview Study. Healthcare, 11(11), 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11111535