Trends in the Consumption of Antidepressant Drugs before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Canary Islands, Spain: The Case of the Province of Las Palmas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethics Approval

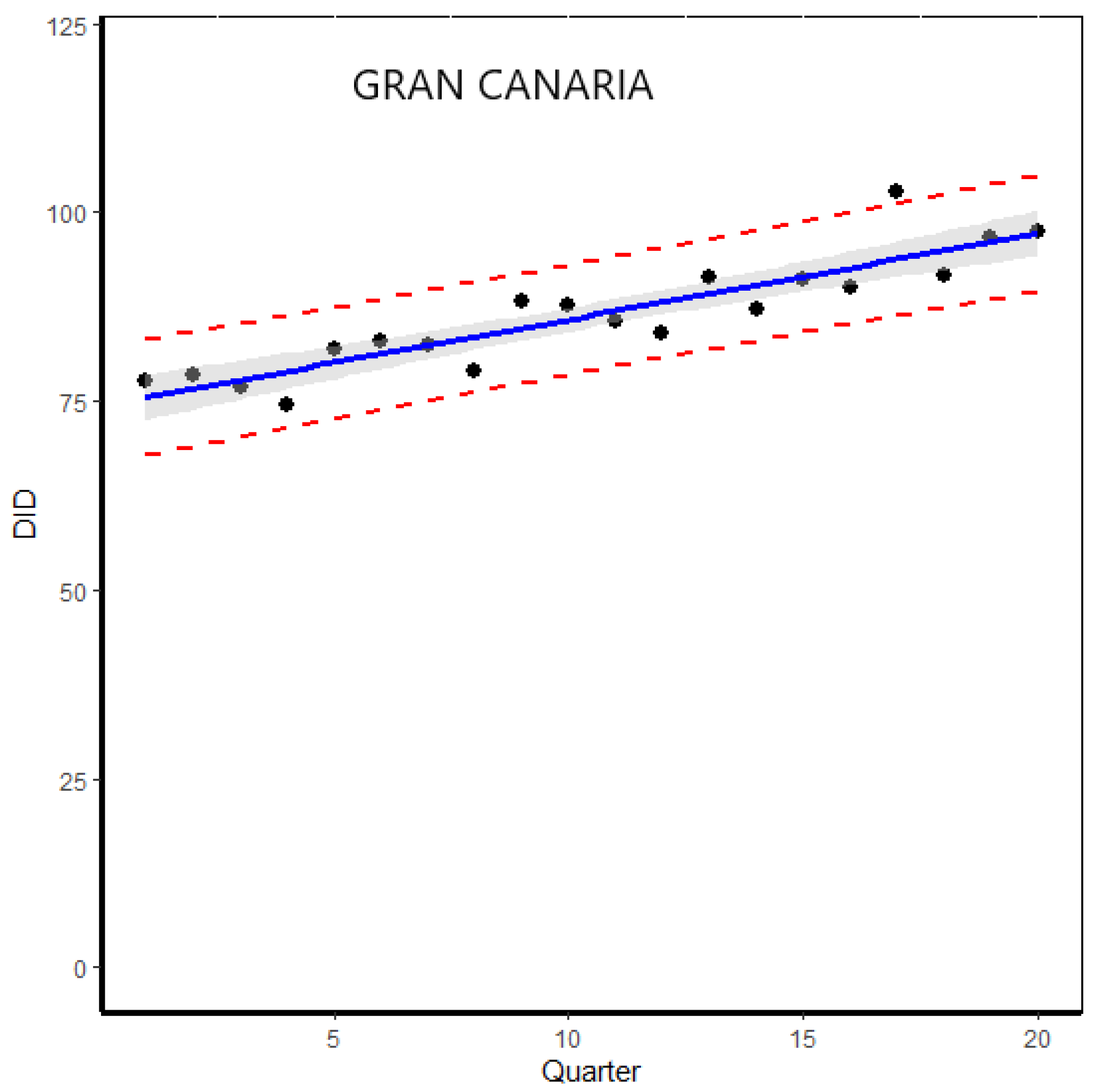

3. Results

3.1. Population and Demographic Data

3.2. Analysis by Overall DID

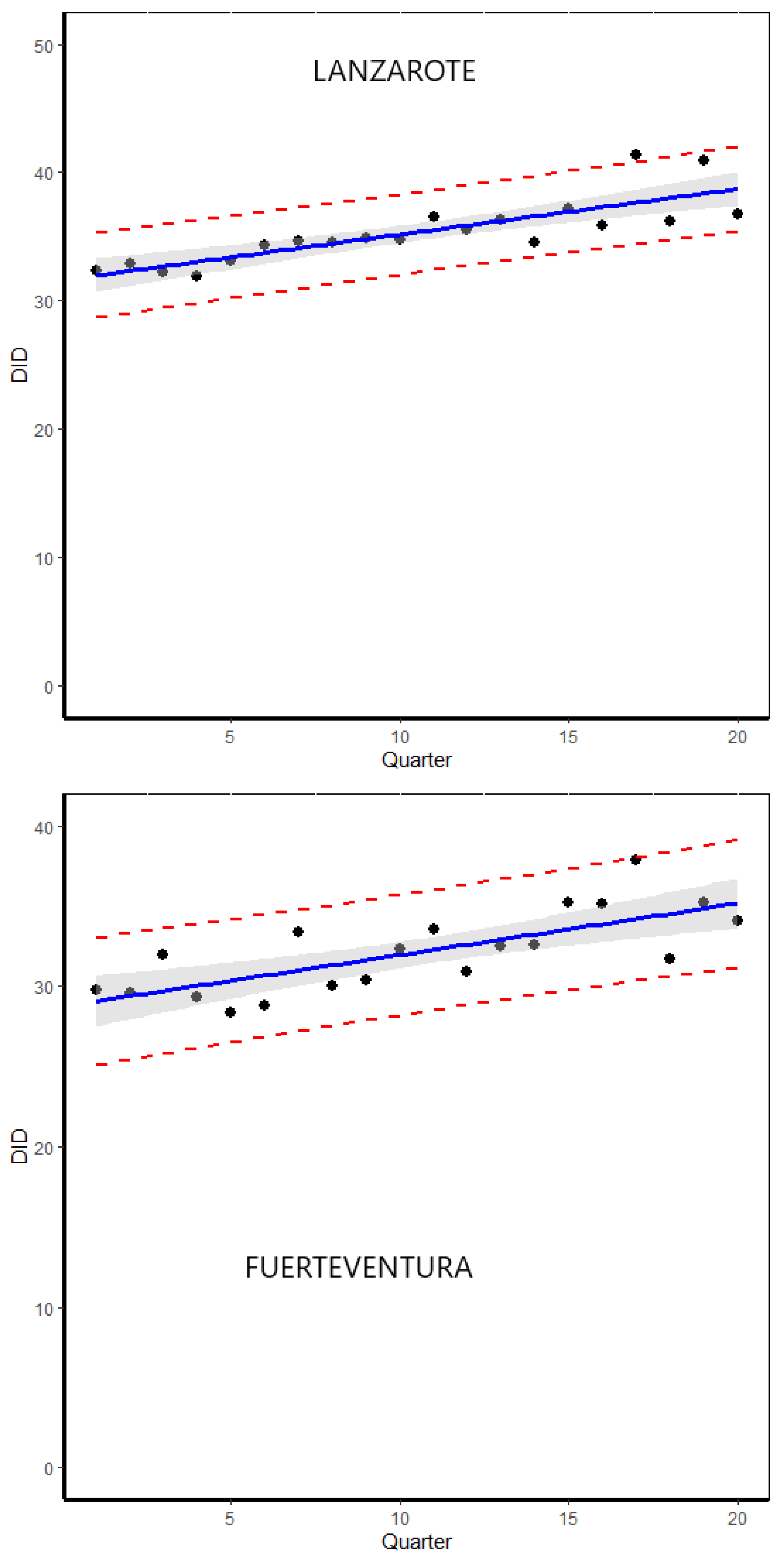

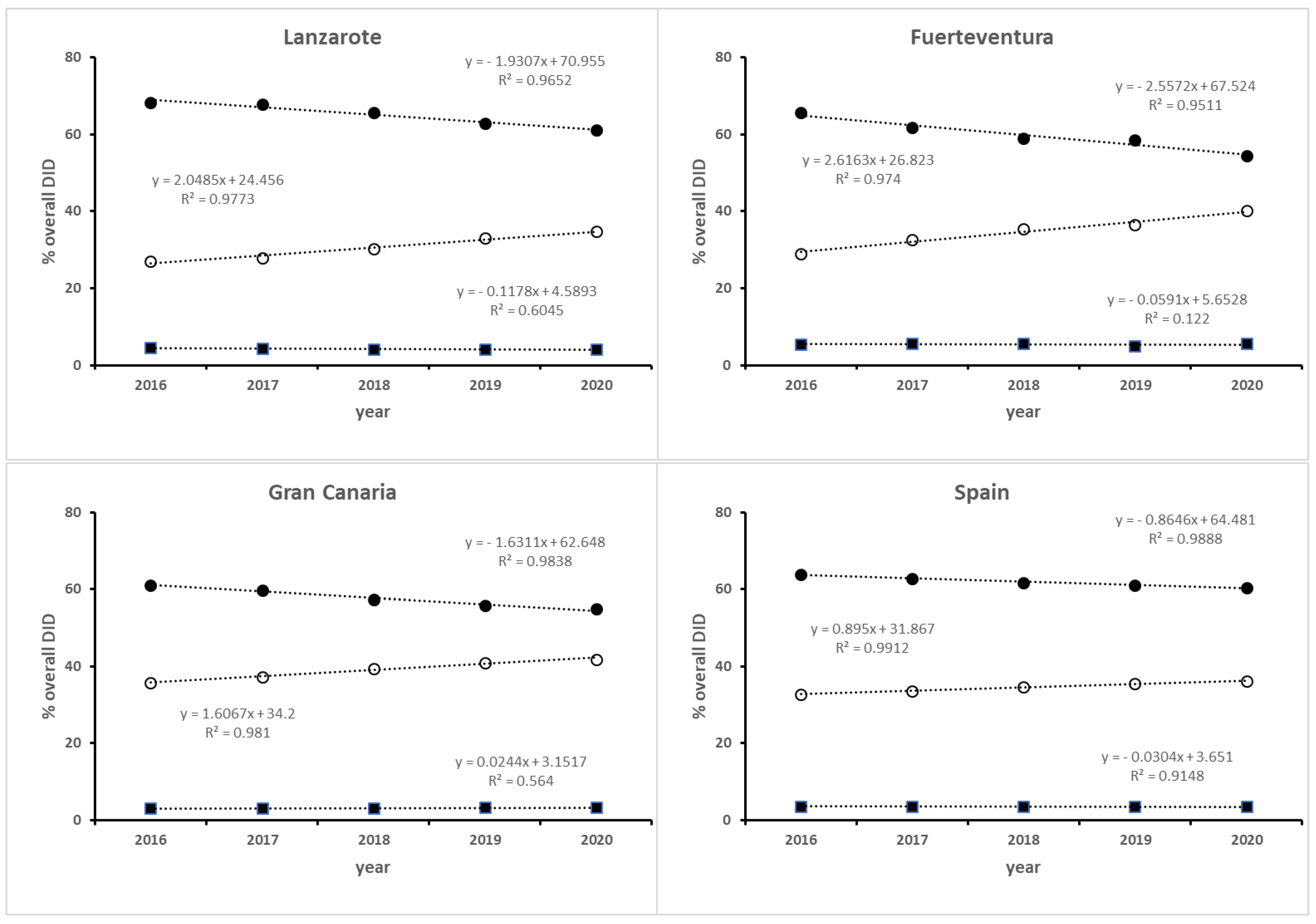

3.3. Analysis by Antidepressants Drug and Classes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harapan, H.; Itoh, N.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Keam, S.; Te, H.; Megawati, D.; Hayati, Z.; Wagner, A.L.; Mudatsir, M. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Dalexis, R.D.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Mukunzi, J.N.; Rousseau, C. Social inequalities and collateral damages of the COVID-19 pandemic: When basic needs challenge mental health care. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 717–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Dosil-Santamaria, M.; Picaza-Gorrochategui, M.; Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. Stress, anxiety and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cad Saude Publica 2020, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ettman, C.K.; Abdalla, S.M.; Cohen, G.H.; Sampson, L.; Vivier, P.M.; Galea, S. Prevalence of Depression Symptoms in US Adults Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus and Depression in Adults, Great Britain: June 2020. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/coronavirusanddepressioninadultsgreatbritain/june2020 (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Ren, X.; Huang, W.; Pan, H.; Huang, T.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y. Mental Health During the Covid-19 Outbreak in China: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Q. 2020, 91, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, J.; Koskinen, A.; Varje, P.; Kouvonen, A.; Hakanen, J.J.; Väänänen, A. Mental health by gender-specific occupational groups: Profiles, risks and dominance of predictors. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 238, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, B.; Heron, J.; Kessler, D.; Davies, N.M.; Martin, R.M.; Thomas, K.H.; Gunnell, D. Influences on antidepressant prescribing trends in the UK: 1995–2011. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.C.; Rodríguez-López, C.M.; Parrón-Carreño, T.; Luna, J.D.; Del Pozo, E. Trends in the dispensation of antidepressant drugs over the past decade (2000–2010) in Andalusia, Spain. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revet, A.; Montastruc, F.; Raynaud, J.P.; Baricault, B.; Montastruc, J.L.; Lapeyre-Mestre, M. Trends and Patterns of Antidepressant Use in French Children and Adolescents from 2009 to 2016. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 38, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Kremers, H.M.; Yawn, B.P.; Bobo, W.V.; St. Sauver, J.L.; Ebbert, J.; Rutten, F.L.J.; Jacobson, D.J.; Brue, S.M.; Rocca, W.A. Time trends of antidepressant drug prescriptions in men versus women in a geographically defined US po-pulation. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2014, 17, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.; Anderson, M.J.; Sutton, M.; Munoz-Arroyo, R.; McDonald, S.; Maxwell, M.; Power, A.; Smith, M.; Wilson, P. Factors influencing variation in prescribing of antidepressants by general practices in Scotland. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2009, 59, e25–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto 1718/2020 de 17 Diciembre 2010 Sobre Recetas Médicas y Órdenes de Dispensación. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2011/BOE-A-2011-1013-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de Diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y Garantía de los Derechos Digitales. BOE Núm. 294, de 06/12/2018. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2018/12/05/3/con (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Oliva, A.; Armas, N.; Dévora, S.; Abdala, S. Opioid use trends in Spain: The case of the island of La Gomera (2016–2019). Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2022, 395, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España (INE). Available online: https://ine.es (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Ministerio de Sanidad de España. Consumo de Medicamentos en Recetas Médicas Dispensadas en Oficinas de Farmacia con Cargo al Sistema Nacional de Salud Según Clasificación Anatómica-Terapéutica-Química (ATC). Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/ConsumoRecetasATC/home.htm (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2021. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Reig, E.; Goerlich, F.J.; Cantarino, I. Delimitación de Áreas Rurales y Urbanas a Nivel Local. Demografía, Coberturas del Suelo y Accesibilidad; Editorial Ibersaf Industrial, S.L.; Fundación BBVA: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 40–80. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto de Estadística de Canarias (ISTAC). Available online: http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/ (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Hernandez, J.F.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.; van Thiel, G.J.M.W.; Belitser, S.V.; Warmerdam, J.; de Valk, V.; Raaijmakers, J.A.M.; Pieters, T. A 10-Year Analysis of the Effects of Media Coverage of Regulatory Warnings on Antidepressant Use in The Netherlands and UK. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parabiaghi, A.; Franchi, C.; Tettamanti, M.; Barbato, A.; D’Avanzo, B.; Fortino, I.; Bortolotti, A.; Merlino, L.; Nobili, A. Antidepressants utilization among elderly in Lombardy from 2000 to 2007: Dispensing trends and appropriateness. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualano, M.R.; Bert, F.; Mannocci, A.; La Torre, G.; Zeppegno, P.; Siliquini, R. Consumption of antidepressants in Italy: Recent trends and their significance for public health. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Arias, L.H.; Treceño-Lobato, C.; Ortega, S.; Velasco, A.; Carvajal, A.; García del Pozo, J. Trends in the consumption of antidepressants in Castilla y León (Spain). Association between suicide rates and antidepressant drug consumption. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2010, 19, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selke, I.; Selke, G.W.; Thürmann, P.A. Trends and patterns in EU (7)-PIM prescribing to elderly patients in Germany. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.; Monz, B.; Montejo, A.; Quail, D.; Dantchev, N.; Demyttenaere, K.; Garcia-Cebrian, A.; Grassi, L.; Perahia, D.G.S.; Reed, C.; et al. Prescribing patterns of antidepressants in Europe: Results from the Factors Influencing Depression Endpoints Research (FINDER) study. Eur. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalji, H.M.; McGrogan, A.; Bailey, S.J. An analysis of antidepressant prescribing trends in England 2015–2019. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 6, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabeea, S.A.; Merchant, H.A.; Khan, M.U.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. Surging trends in prescriptions and costs of antidepressants in England amid COVID-19. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 29, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, A.L.; Zhou, H.J.; Teng, M.; Lin, L.; Zhao, Y.J.; Soh, L.B.; Mok, Y.M.; Lim, B.P.; Gwee, K.P. Network Meta-Analysis and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of New Generation Antidepressants. CNS Drugs 2015, 29, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyding, D.; Lelgemann, M.; Grouven, U.; Härter, M.; Kromp, M.; Kaiser, T.; Kerekes, M.F.; Gerken, M.; Wieseler, B. Reboxetine for acute treatment of major depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished placebo and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-controlled trials. BMJ 2010, 341, c4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Focus 2018, 16, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salagre, E.; Grande, I.; Solé, B.; Sánchez-Moreno, J.; Vieta, E. Vortioxetina: Una nueva alternativa en el trastorno depresivo mayor. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2018, 11, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Abejón, E.; Herrera-Gómez, F.; Criado-Espegel, P.; Álvarez, F.J. Trends in Antidepressants Use in Spain between 2015 and 2018: Analyses from a Population-Based Registry Study with Reference to Driving. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Population Density | Over- 65 Years (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Island | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | %∆ | 2020 | 2020 |

| Gran Canaria | 845,195 | 843,158 | 846,717 | 851,231 | 855,521 | 0.5 | 548.4 | 16.97 |

| Lanzarote | 145,084 | 147,023 | 149,183 | 152,289 | 155,812 | 2.31 | 184.2 | 12.57 |

| Fuerteventura | 107,521 | 110,299 | 113,275 | 116,886 | 119,732 | 2.43 | 72.1 | 11.11 |

| Province | 1,097,800 | 1,100,480 | 1,109,175 | 1,120,406 | 1,131,065 | 0.95 | 278.2 | 13.07 |

| Year | Province | Gran Canaria | Lanzarote | Fuerteventura | Spain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 66.39 | 76.84 | 32.36 | 30.15 | 75.47 |

| 2017 | 70.06 | 81.54 | 34.17 | 30.11 | 77.21 |

| 2018 | 73.92 | 86.34 | 35.43 | 31.76 | 79.91 |

| 2019 | 76.80 | 90.00 | 36.00 | 33.84 | 83.07 |

| 2020 | 82.45 | 97.08 | 38.83 | 34.67 | 86.28 |

| 2020 * | 81.70 | 96.14 | 38.31 | 34.66 | 85.88 |

| Subgroup | Lanzarote | Fuerteventura | Gran Canaria | Province | Spain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N06AA | 4.24 ± 0.24 | 5.48 ± 0.27 | 3.22 ± 0.05 | 3.39 ± 0.04 | 3.56 ± 0.05 |

| N06AB | 65.16 ± 3.11 | 59.85 ± 4.14 | 57.76 ± 2.60 | 58.32 ± 2.69 | 61.89 ± 1.37 |

| N06AX | 30.60 ± 3.28 | 34.67 ± 4.19 | 39.02 ± 2.56 | 38.28 ± 2.67 | 34.55 ± 1.42 |

| Subgroup | Coefficients | Estimate | 2.5% | 97.5% | Pr(>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N06AA (TCAs) | Intercept 1 | 5.65 | 5.19 | 6.12 | <0.01 * |

| Year 1 | −0.059 | −0.200 | 0.081 | 0.366 | |

| Gran Canaria | −2.50 | −3.16 | −1.84 | <0.01 * | |

| Lanzarote | −1.06 | −1.72 | −0.40 | <0.01 * | |

| year × Gran Canaria | 0.083 | −0.11 | 0.28 | 0.366 | |

| year × Lanzarote | −0.059 | −0.26 | 0.14 | 0.520 | |

| N06AB (SSRIs) | Intercept 1 | 67.52 | 65.73 | 69.32 | <0.01 * |

| Year 1 | −2.56 | −3.10 | −2.02 | <0.01 * | |

| Gran Canaria | −4.88 | −7.41 | −2.34 | <0.01 * | |

| Lanzarote | 3.43 | 0.89 | 5.97 | 0.014 * | |

| year × Gran Canaria | 0.926 | 0.16 | 1.69 | 0.0229 | |

| year × Lanzarote | 0.626 | −0.14 | 1.39 | 0.0969 | |

| N06AX (other ADs) | Intercept 1 | 26.82 | 25.38 | 28.26 | <0.01 * |

| Year 1 | 2.62 | 2.18 | 3.05 | <0.01 * | |

| Gran Canaria | 7.38 | 5.34 | 9.41 | <0.01 * | |

| Lanzarote | −2.37 | −4.40 | −0.33 | 0.0271 * | |

| year × Gran Canaria | −1.01 | −1.62 | −0.40 | <0.01 * | |

| year × Lanzarote | −0.568 | −1.18 | 0.045 | 0.0656 |

| Subgroup/API | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ∆ (%) 2018–2019 | ∆ (%) 2019–2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N06AA | 2.46 | 2.60 | 2.85 | 5.69 | 9.61 |

| N06AA02-Imipramine | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.00 |

| N06AA04-Clomipramine | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 9.1 | 10.00 |

| N06AA09-Amitriptiline | 2.28 | 2.44 | 2.68 | 7.20 | 9.84 |

| N06AA10-Nortriptiline | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| N06AA12-Doxepin | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| N06AA21-Maprotiline | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −50 | −100 |

| N06AB | 42.89 | 43.28 | 45.56 | 0.91 | 5.27 |

| N06AB03-Fluoxetine | 5.73 | 5.74 | 5.88 | 0.17 | 2.44 |

| N06AB04-Citalopram | 4.81 | 4.81 | 4.98 | 0.00 | 3.53 |

| N06AB05-Paroxetine | 8.20 | 8.14 | 8.89 | 0.73 | 9.21 |

| N06AB06-Sertraline | 12.69 | 13.14 | 14.11 | 3.55 | 7.38 |

| N06AB08-Fluvoxamine | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.21 | −4.17 | 0.00 |

| N06AB10-Escitalopram | 11.22 | 11.21 | 11.48 | 0.01 | 2.41 |

| N06AX | 28.57 | 30.92 | 34.05 | 8.23 | 10.12 |

| N06AX03-Mianserin | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −90.9 | 0.00 |

| N06AX05-Trazodona | 4.52 | 4.77 | 5.26 | 5.53 | 10.27 |

| N06AX11-Mirtazapini | 5.13 | 5.32 | 5.75 | 3.70 | 8.08 |

| N06AX12-Bupropion | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 1.64 | 5.00 |

| N06AX14-Tianeptine | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 78.95 | 8.82 |

| N06AX16-Venlafaxine | 5.15 | 5.21 | 5.65 | 1.17 | 8.44 |

| N06AX18-Reboxetine | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −12.50 | −14.28 |

| N06AX21-Duloxetine | 4.47 | 4.81 | 5.08 | 7.61 | 5.61 |

| N06AX22-Agomelatine | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 4.21 | −15.15 |

| N06AX23-Desvenlafaxine | 5.24 | 6.00 | 6.76 | 14.50 | 12.67 |

| N06AX26-Vortioxetine | 2.02 | 2.80 | 3.63 | 38.61 | 29.64 |

| Overall DID | 73.92 | 76.80 | 82.45 | 3.90% | 7.35% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno, V.; Dévora, S.; Abdala-Kuri, S.; Oliva, A. Trends in the Consumption of Antidepressant Drugs before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Canary Islands, Spain: The Case of the Province of Las Palmas. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101425

Moreno V, Dévora S, Abdala-Kuri S, Oliva A. Trends in the Consumption of Antidepressant Drugs before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Canary Islands, Spain: The Case of the Province of Las Palmas. Healthcare. 2023; 11(10):1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101425

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno, Vanessa, Sandra Dévora, Susana Abdala-Kuri, and Alexis Oliva. 2023. "Trends in the Consumption of Antidepressant Drugs before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Canary Islands, Spain: The Case of the Province of Las Palmas" Healthcare 11, no. 10: 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101425

APA StyleMoreno, V., Dévora, S., Abdala-Kuri, S., & Oliva, A. (2023). Trends in the Consumption of Antidepressant Drugs before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Canary Islands, Spain: The Case of the Province of Las Palmas. Healthcare, 11(10), 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101425