Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validity of a Hebrew Version of the Physiotherapist Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Adjusted to Low Back Pain Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. The Translation Procedure

2.2. Psychometric Evaluation

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. PSE Hebrew Reliability

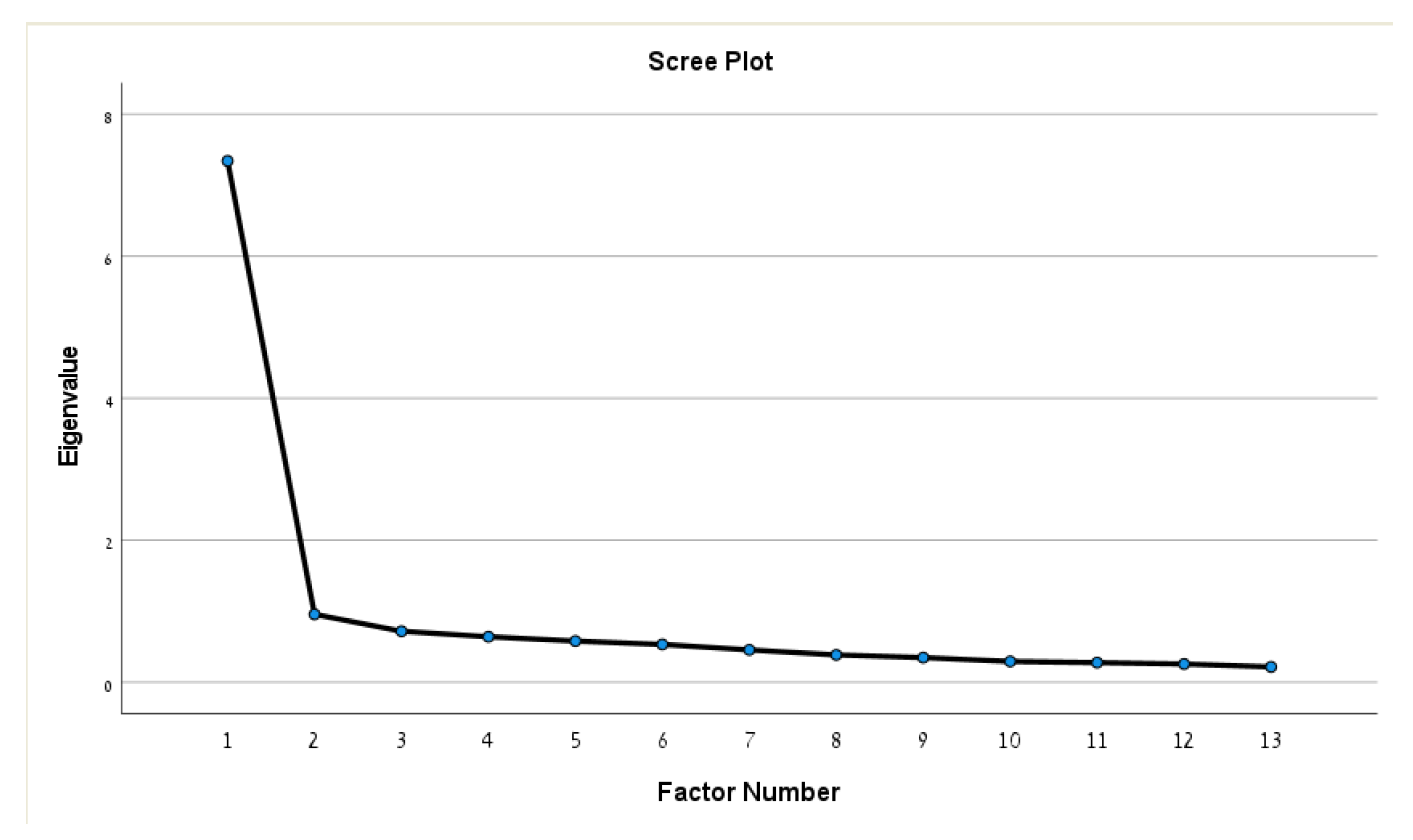

3.3. Internal Structure and Construct Validity

3.4. PSE Score Results

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Original Physiotherapist Self-Efficacy (PSE) Questionnaire

| Item | Wording of Item |

|---|---|

| 1 | I feel adequately prepared to undertake a ….. caseload. |

| 2 | I feel that I am able to verbally communicate effectively and appropriately for a …. caseload. |

| 3 | I feel that I am able to communicate in writing effectively and appropriately for a …. caseload. |

| 4 | I feel that I am able to perform subjective assessments for a …. caseload. |

| 5 | I feel that I am able to perform objective assessment for a …. caseload. |

| 6 | I feel that I am able to interpret assessment findings appropriate for a …. caseload. |

| 7 | I feel that I am able to identify and prioritize patient’s problems for a …. caseload. |

| 8 | I feel that I am able to select appropriate short- and long-term goals for a …. caseload. |

| 9 | I feel that I am able to appropriately perform treatments for a …. caseload. |

| 10 | I feel that I am able to perform discharge planning for a …. caseload. |

| 11 | I feel that I am able to evaluate my treatments for a …. caseload. |

| 12 | I feel that I am able to progress interventions appropriately for a …. caseload. |

| 13 | I feel that I am able to deal with the range of patient conditions which may be seen with a …. caseload. |

References

- Ferreira, P.H.; Ferreira, M.L.; Maher, C.G.; Refshauge, K.M.; Latimer, J.; Adams, R.D. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, L.; Gm, J. Using clinical outcomes to explore the theory of expert practice in physical therapy. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14640868/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Vision Statement for the Physical Therapy Profession. APTA. Published 25 September 2019. Available online: https://www.apta.org/apta-and-you/leadership-and-governance/policies/vision-statement-for-the-physical-therapy-profession (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy. I: V. S. Ramachandran (red.), Encyclopedia of Human Behavior (vol. s.); Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; undefined; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Self-efficacy.-I%3A-V.-S.-Ramachandran-(red.)%2C-of-s.-Bandura/00dee52a4d1d98e48ed052af174e2e8bcad71563 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Gallagher, A.M.; Kaufman, J.C. Gender Differences in Mathematics: An Integrative Psychological Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1986; p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, L.M.; Black, L.L.; Mostrom, E.; Jensen, G.M.; Ritzline, P.D.; Perkins, J. The first two years of practice: A longitudinal perspective on the learning and professional development of promising novice physical therapists. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, B.; Lucarelli, J.; Ingman, M.; Briskey, C. Changes in Physical Therapist Students’ Self-Efficacy for Physical Activity Counseling Following a Motivational Interviewing Learning Module. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2016, 30, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithman, R.W.; Spiegel, J.J.; Lorello, D. Effect of High-Fidelity ICU Simulation on a Physical Therapy Student’s Perceived Readiness for Clinical Education. J. Acute Care Phys. Ther. 2016, 7, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtake, P.J.; Lazarus, M.; Schillo, R.; Rosen, M. Simulation experience enhances physical therapist student confidence in managing a patient in the critical care environment. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberman, N.J.; Litwin, B.; Panzarella, K.J.; Fernandez-Fernandez, A. High Fidelity Human Simulation Improves Physical Therapist Student Self-Efficacy for Acute Care Clinical Practice. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2016, 30, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberman, N.J.; Litwin, B.; Panzarella, K.J.; Fernandez-Fernandez, A. Student Clinical Performance in Acute Care Enhanced Through Simulation Training. J. Acute Care Phys. Ther. 2016, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales. Self-Effic. Beliefs Adolesc. 2006, 5, 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.; Sheppard, L. Developing a measurement tool for assessing physiotherapy students’ self-efficacy: A pilot study. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 2012, 37, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lankveld, W.; Maas, M.; van Wijchen, J.; Visser, V.; Staal, J.B. Self-regulated learning in physical therapy education: A non-randomized experimental study comparing self-directed and instruction-based learning. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.; Brismée, J.M.; Allen, B.; Hooper, T.; Domenech, M.; Manella, K. Doctor of Physical Therapy students’ clinical reasoning readiness and confidence treating with telehealth: A United States survey. J. Clin. Educ. Phys. Ther. 2022, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venskus, D.G.; Craig, J.A. Development and Validation of a Self-Efficacy Scale for Clinical Reasoning in Physical Therapists. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2017, 31, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 328 Diseases and Injuries for 195 Countries, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016—The Lancet. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)32154-2/fulltext (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Hartvigsen, J.; Hancock, M.J.; Kongsted, A.; Louw, Q.; Ferreira, M.L.; Genevay, S.; Hoy, D.; Karppinen, J.; Pransky, G.; Sieper, J.; et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018, 391, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.A.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Study Design Checklist for Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Instruments; Amsterdam University Medical Centers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kottner, J.; Audigé, L.; Brorson, S.; Donner, A.; Gajewski, B.J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Roberts, C.; Shoukri, M.; Streiner, D.L. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lankveld, W.; Jones, A.; Brunnekreef, J.J.; Seeger, J.P.H.; Bart Staal, J. Assessing physical therapist students’ self-efficacy: Measurement properties of the Physiotherapist Self-Efficacy (PSE) questionnaire. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, P.; Caneiro, J.P.; O’Keeffe, M.; O’Sullivan, K. Unraveling the Complexity of Low Back Pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hush, J.M. Low back pain: It is time to embrace complexity. Pain 2020, 161, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics XM—Experience Management Software. Qualtrics. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Polit, D.F. Getting serious about test-retest reliability: A critique of retest research and some recommendations. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainapel, S.; Shamir, O.Y.; Tenenbaum, Y.; Gilam, G. The dark side of gendered language: The masculine-generic form as a cause for self-report bias. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; p. 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuban, C.D.; Shirkey, E.C. When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis? Some decision rules. Psychol. Bull. 1974, 81, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations fo” by Anna B Costello and Jason Osborne. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol10/iss1/7/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Timmerman, M.E.; Kiers, H.A.L. The Hull Method for Selecting the Number of Common Factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J. Multivariate Data Analysis. Faculty Publications. Published online 23 February 2009. Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facpubs/2925 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Portney, L.G. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Evidence-Based Practice; F.A. Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.A. A Meta-Analysis of Variance Accounted for and Factor Loadings in Exploratory Factor Analysis. Mark. Lett. 2000, 11, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merenda, P.F. A Guide to the Proper Use of Factor Analysis in the Conduct and Reporting of Research: Pitfalls to Avoid. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 1997, 30, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (Years) | 38 ± 9.8 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 173 (55.1%) |

| Male | 141 (44.9%) |

| Experience (years) | 10 ± 9.9 |

| Postgraduate academic education | 92 (29%) |

| Employment | |

| Health maintenance organizations’ outpatient clinic | 169 (53.6%) |

| Private practice | 77 (24.5%) |

| Hospital setting | 20 (6.4%) |

| Inpatients rehabilitation center | 19 (6.2%) |

| Others (non-specified) | 29 (9.3%) |

| PSE Items | Initial | Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.692 | 0.668 |

| 2 | 0.560 | 0.532 |

| 3 | 0.516 | 0.477 |

| 4 | 0.530 | 0.476 |

| 5 | 0.630 | 0.573 |

| 6 | 0.637 | 0.644 |

| 7 | 0.576 | 0.552 |

| 8 | 0.445 | 0.388 |

| 9 | 0.650 | 0.635 |

| 10 | 0.560 | 0.505 |

| 11 | 0.430 | 0.347 |

| 12 | 0.662 | 0.659 |

| 13 | 0.441 | 0.434 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shavit, R.; Kushnir, T.; Gottlieb, U.; Springer, S. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validity of a Hebrew Version of the Physiotherapist Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Adjusted to Low Back Pain Treatment. Healthcare 2023, 11, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010085

Shavit R, Kushnir T, Gottlieb U, Springer S. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validity of a Hebrew Version of the Physiotherapist Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Adjusted to Low Back Pain Treatment. Healthcare. 2023; 11(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleShavit, Ron, Talma Kushnir, Uri Gottlieb, and Shmuel Springer. 2023. "Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validity of a Hebrew Version of the Physiotherapist Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Adjusted to Low Back Pain Treatment" Healthcare 11, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010085

APA StyleShavit, R., Kushnir, T., Gottlieb, U., & Springer, S. (2023). Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validity of a Hebrew Version of the Physiotherapist Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Adjusted to Low Back Pain Treatment. Healthcare, 11(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010085