Addressing the Gap in Data Communication from Home Health Care to Primary Care during Care Transitions: Completeness of an Interoperability Data Standard

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Mapping of OASIS to Transition of Care

2.2. Identification of a Parsimonious OASIS Data Set for the Transition of Care Visit

2.3. Assess Completeness of LOINC

3. Results

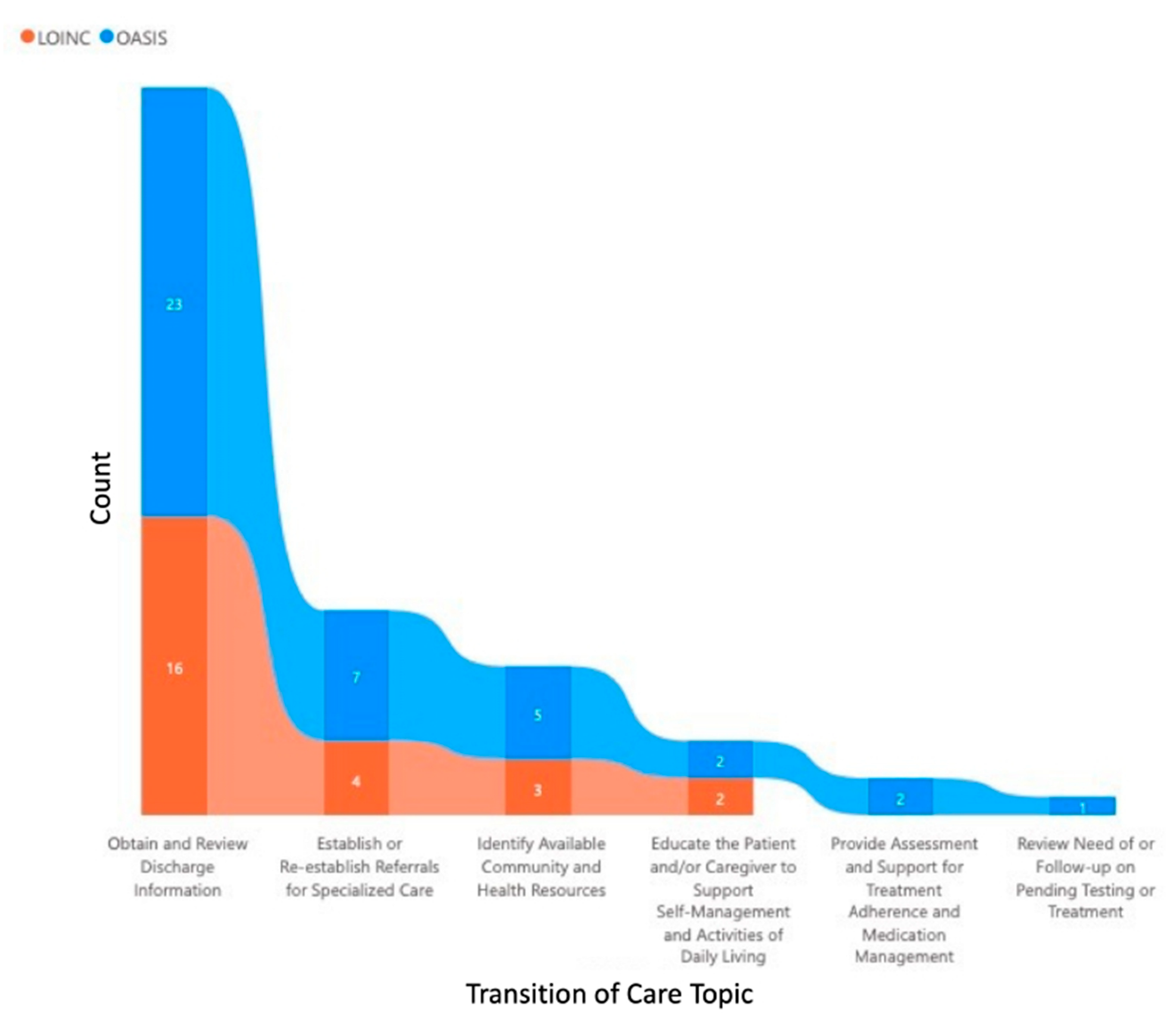

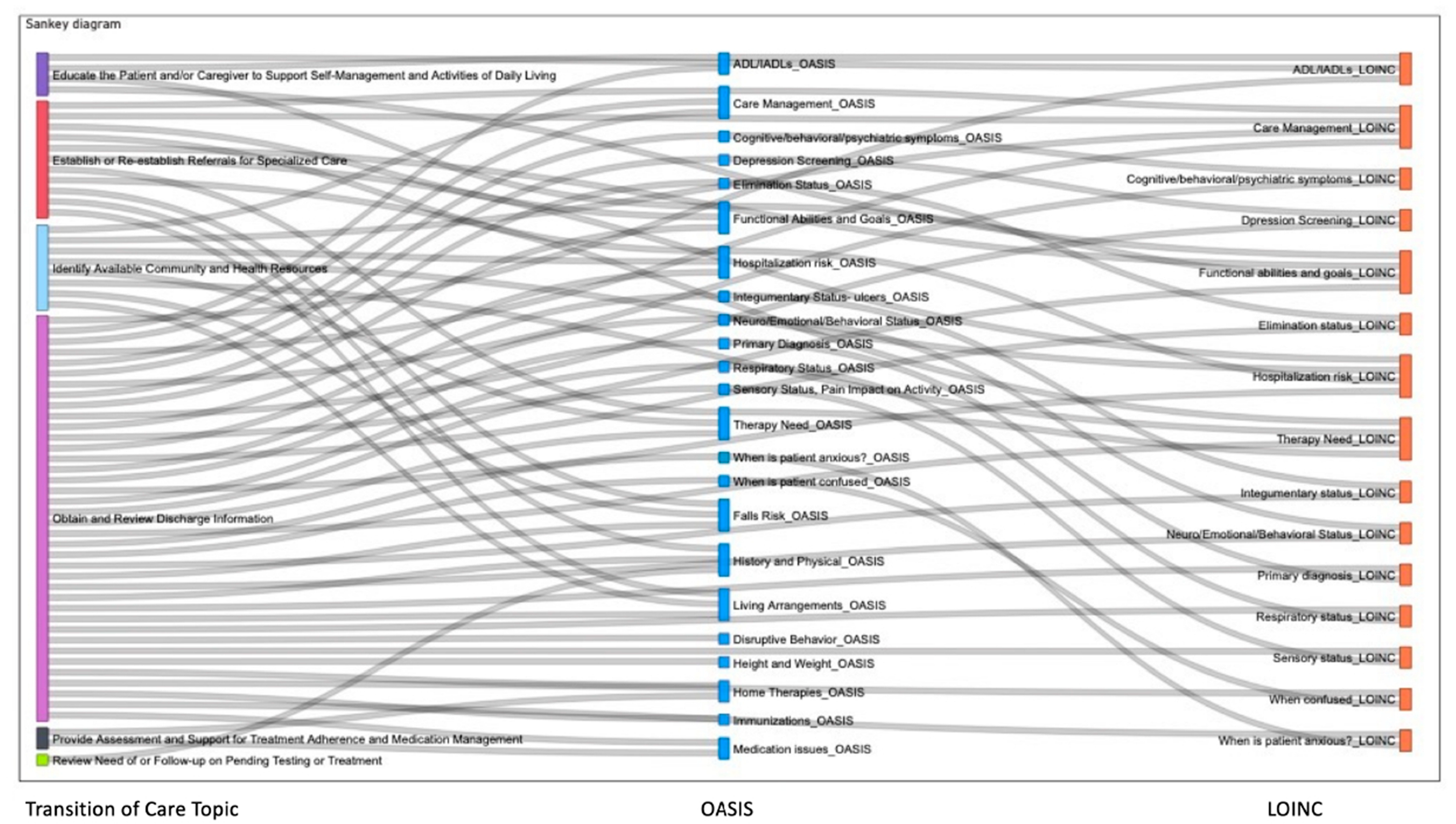

3.1. Mapping of OASIS to Transition of Care

3.2. Identification of a Parsimonious OASIS Data Set for the Transition of Care Visit

3.2.1. Focus Groups

- The question stem should communicate information available in the response choices;

- Data for all questions should be communicated regardless of whether the patient has a deficit. Therefore, the survey response should be whether the data is needed or not needed.

3.2.2. Survey Administration

3.3. Assess Completeness of LOINC

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegler, E.L.; Murtaugh, C.M.; Rosati, R.J.; Schwartz, T.; Razzano, R.; Sobolewski, S.; Callahan, M. Improving communication at the transition to home health care: Use of an electronic referral system. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2007, 19, 267–271. Available online: www.cinahl.com/cgi-bin/refsvc?jid=504&accno=2009636652; http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=2009636652&site=ehost-live (accessed on 23 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Pesko, M.F.; Gerber, L.M.; Peng, T.R.; Press, M.J. Home Health Care: Nurse-Physician Communication, Patient Severity, and Hospital Readmission. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 53, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C.M.; Leff, B.; Bellantoni, J.; Rana, N.; Wolff, J.L.; Roth, D.L.; Carl, K.; Sheehan, O.C. Interactions between physicians and skilled home health care agencies in the certification of Medicare beneficiaries’ plans of care: Results of a nationally representative survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 168, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sockolow, P.S.; Bowles, K.; Wojciechowicz, C.; Bass, E.J. Incorporating home health care nurses’ admission information needs: Informing data standards. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helleso, R.; Sockolow, P.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Cummings, E. Interoperability of home health care information across care settings: Challenges of flow from hospital to home. In Proceedings of the 15th World Congress on Health and Biomedical Informatics (MedInfo 2015), Sao Paulo, Brazil, 19–23 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sockolow, P.S.; Bowles, K.H.; Topaz, M.; Koru, G.; Helleso, R.; O’Connor, M.; Bass, E.J. The time is now: Informatics research opportunities in home health care. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson Helms, L.B.; Black, S.; Myers, D.K. A rural perspective on home care communication about elderly patients after hospital discharge. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2000, 22, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System; National Academies Press: Washington, WA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kripalani, S.; LeFevre, F.; Phillips, C.O.; Williams, M.V.; Basaviah, P.; Baker, D.W. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: Implications for patient safety and continuity of care. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 297, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 2017: Home Care Accreditation Program. 2017. Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/NPSG_Chapter_OME_Jan2017.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Brody, A.; Gibson, B.; Tresner-Kirsch, D.; Kramer, H.M.; Thraen, I.; Coarr, M.E.; Ruppert, R. High prevalence of medication discrepancies between home health referrals and centers for medicare and medicaid services home health certification and plan of care and their potential to affect safety of vulnerable elderly adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferranti, J.M.; Musser, R.C.; Kawamoto, K.; Hammond, W.E. The Clinical Document Architecture and the Continuity of Care Record: A critical analysis. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006, 13, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykes, P.C.; Samal, L.; Donahue, M.; Greenberg, J.O.; Hurley, A.C.; Hasan, O.; O’Malley, T.A.; Venkatesh, A.K.; Volk, L.A.; Bates, D.W. A patient-centered longitudinal care plan: Vision versus reality. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2014, 21, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visiting Nurse Associations of America. Blueprint for Excellence. Prevent Readmissions/Promote Community Stay. 2019. Available online: https://www.elevatinghome.org/preventingreadmit+dtc (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Quality Insights. Performance Improvement Practice Project (PIP) Tool. (11SOW-WV-HH-MMD-110918). H. H. Q. Improvement. 2018. Available online: http://www.homehealthquality.org/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=feb482d5-48e0-44d9-9354-9543bff03571 (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Bindman, A.; Cox, D. Changes in health care costs and mortality associated with transitional care management services after a discharge among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Famly Physicians. FAQ on Transitional Care Management. 2020. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/practice-and-career/getting-paid/coding/transitional-care-management/faq.html#care (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Deb, P.; Murtaugh, C.M.; Bowles, K.H.; Mikkelsen, M.E.; Khajavi, H.N.; Moore, S.; Barron, Y.; Feldman, P.H. Does early follow-up improve the outcomes of sepsis survivors discharged to home health care? Med. Care 2019, 57, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaugh, C.M.; Deb, P.; Zhu, C.; Peng, T.R.; Barron, Y.; Shah, S.; Moore, S.M.; Bowles, K.H.; Kalman, J.; Feldman, P.H.; et al. Reducing readmissions among heart failure patients discharged to home health care: Effectiveness of early and intensive nursing services and early physician follow-up. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 52, 1445–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HL7/ASTM Implementation Guide for CDA® R2-Continuity of Care Document (CCD) Release 1. Available online: http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/product_brief.cfm?product_id=6 (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Helleso, R.; Fagermoen, M.S. Cultural diversity between hospital and community nurses: Implications for continuity of care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2010, 10, e036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sockolow, P.S.; Le, N.; Potashnik, S.; Bass, E.J.; Yang, Y.; Pankok, C.; Champion, C.L.; Bowles, K.H. There’s a problem with the problem list: Patterns of patient problem occurrence across phases of the home care admission. JAMDA 2021, 22, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champion, C.L.; Sockolow, P.S.; Bowles, K.H.; Potashnik, S.; Yang, Y.; Pankok, C.; Le, N.; McLaurin, E.; Bass, E.J. Getting to complete and accurate medication lists during the transition to home health care. JAMDA 2021, 22, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Outcome and Assessment Information Set. 16 May 2022. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/HHQIOASISUserManual (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Chou, E.; Sockolow, P. Transitions of Care: Completeness of the Interoperability Data Standard for Communication from Home Health Care to Primary Care. In Proceedings of the AMIA 2021 Annual Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 October–3 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- What LOINC Is. 2021. Available online: https://loinc.org/get-started/what-loinc-is/ (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Vreeman, D.J.; McDonald, C.J.; Huff, S.M. LOINC®—A Universal Catalog of Individual Clinical Observations and Uniform Representation of Enumerated Collections. Int. J. Funct. Inform. Pers. Med. 2010, 3, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jenkins, M.L.; Cimino, J.J.; White, T.M.; Bakken, S. Toward semantic interoperability in home health care: Formally representing OASIS items for integration into a concept-oriented terminology. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2005, 12, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakken, S.; Cimino, J.J.; Haskell, R.; Kukafka, R.; Matsumoto, C.; Chan, G.K.; Huff, S.M. Evaluation of the clinical LOINC (Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes) semantic structure as a terminology model for standardized assessment measures. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2000, 7, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- American College of Physicians. What Practices Need to Know about Transition Care Management Codes. 2013. Available online: http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2013/02/tips.htm?_ga=2.61554921.410907944.1609769688-1583063500.1609769688 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Bick, I.; Dowding, D. Hospitalization risk factors of older cohorts of home health care patients: A systematic review. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2019, 38, 111–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Transition of Care Topic(s) | Domain | Included in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Clinical status | Yes |

| Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care | Service needs | Yes |

| Educate the Patient and/or Caregiver to Support Self-Management and Activities of Daily Living | Service needs | Yes |

| Review Need for Follow-up on Pending Testing or Treatment | Clinical status | Yes |

| Identify Available Community and Health Resources | Service needs | Yes |

| Provide Assessment and Support for Treatment Adherence and Medication Management | Functional status | Yes |

| Assist in scheduling follow-up with other health services | Service needs | Yes |

| Communicate with a home health agency or other community service that the patient needs | Service needs | Yes |

| Facilitate access to services needed by the patient and/or caregivers | Service needs | Yes |

| Interact with other clinicians who will assume or resume care of the patient’s system-specific conditions | Clinical status | No |

| Transition of Care Topic(s) | Patient Assessment Term(s) Related to OASIS, LOINC Codes | OASIS Question Code | LOINC Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care; Educate the Patient and/or Caregiver to Support Self-Management and Activities of Daily Living | Functional Abilities and Goals: Prior functioning-everyday activities Prior device use Self-care Mobility | GG0100 GG0110 GG0130 GG0170 | 83239-4 83234-5 57245, 89383, 89387–89388, 89393, 89396–89397, 89400–89401, 89405–89407, 89409–89410 57244, 85926-7, 89375–89386, 89390, 89393-5, 89398–9, 89403, 89408, 89411–89421 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Primary Diagnosis Other Diagnoses Active Diagnosis | M1021 M1023 M1028 | 85920, 86255, 88489 85950-4 No corresponding LOINC |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Review Need for Follow-up on Pending Testing or Treatment; Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care | History and Physical | M1100 | 85950-4 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Height and Weight | M1060 | 54567-3 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care; Identify Available Community and Health Resources | Hospitalization risk | M1033 | 57319-6 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care; Identify Available Community and Health Resources | Living Arrangements | M1100 | 85950-4 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Neuro/Emotional/Behavioral Status | M1700 | 46589-8 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | When is patient confused | M1710 | 58104-1 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | When is patient anxious | M1720 | 86495-9 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Cognitive, Behavioral, and Psychiatric Symptoms | M1740 | 46473-5 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Provide Assessment and Support for Treatment Adherence and Medication Management | Home Therapies | M1030 | 46466-9 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Sensory Status, Pain Impact on Activity: Vision Pain frequency | M1200 M1242 | 57215-6 No corresponding LOINC |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Integumentary Status-ulcers: Presence of Stage 2+ pressure ulcer Number of unhealed pressure ulcers at each stage Number Stage 1 pressure ulcers Stage of most problematic pressure ulcer Presence of stasis ulcer Number of stasis ulcers Status of most problematic stasis ulcer Presence of surgical wound Status of most problematic surgical wound | M1306 M1311 M1322 M1324 M1330 M1332 M1334 M1340 M1342 | 85918-1 88494-0 No corresponding LOINC No corresponding LOINC No corresponding LOINC No corresponding LOINC No corresponding LOINC No corresponding LOINC No corresponding LOINC |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Respiratory Status | M1400 | 57237-0 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Elimination Status: Treated for urinary tract infection past 14 days Urinary incontinence or urinary catheter present Bowel incontinence frequency Ostomy | M1600 M1610 M1620 M1630 | 46552-6 46553-4 46587-2 86471-0 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Depression Screening | M1730 | 57242-0 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information | Disruptive Behavior | M1745 | 46592-2 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Educate the Patient and/or Caregiver to Support Self Management and Activities of Daily Living | ADLs: Grooming Dress upper body Dress lower body Bathe Toilet transfer Toileting Transferring Ambulation Feeding | M1800 M1810 M1820 M1830 M1840 M1845 M1850 M1860 M1870 | 46595-5 46597-1 46599-7 57243-8 57244-6 57245-3 57246-1 57247-9 57248-7 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care; Identify Available Community and Health Resources | Falls Risk | M1910 | 57254-5 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Provide Assessment and Support for Treatment Adherence and Medication Management | Medication Issues: Drug regimen review Medication follow-up Medication intervention Oral medication management Injectable medication management | M2001 M2003 M2005 M2020 M2030 | 57255-2 57281-8 57256-0 57285-9 57284-2 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care; Identify Available Community and Health Resources | Care Management | M2102 | 88465-0 |

| Obtain and Review Discharge Information; Establish or Re-establish Referrals for Specialized Care; Identify Available Community and Health Resources | Therapy Need | M2200 | 57268-5 |

| N | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <40 | 3 |

| 40–55 | 3 |

| 56–75 | 6 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 3 |

| Male | 10 |

| Clinical Role | |

| Nurse | 0 |

| Physician | 12 |

| Years in clinical practice | |

| <5 | 2 |

| 5–10 | 1 |

| 11–20 | 2 |

| >20 | 7 |

| Work with care coordination team | |

| Yes | 9 |

| No | 3 |

| Electronic health record system used in primary care | |

| EPIC | 10 |

| Cerner | 1 |

| e-ClinicalWorks | 1 |

| Concept | # Responses = Needed | # Responses = Not Needed |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital Risk Predictors (e.g., falls, multiple hospitalizations/ER visits, mental status decline) | 12 | 0 |

| Living Arrangement (alone; availability of assistance) | 12 | 0 |

| Vision impairment (e.g., cannot read medication labels) | 11 | 1 |

| If Pain experienced: frequency | 10 | 2 |

| Stasis ulcers presence, status | 12 | 0 |

| Dyspnea presence, severity | 10 | 2 |

| Urinary Tract Infection in past 14 days | 8 | 4 |

| Urinary Incontinence or catheter presence | 11 | 1 |

| Bowel Incontinence frequency | 11 | 1 |

| Bowel Ostomy status | 11 | 1 |

| Cognitive functioning (e.g., level of alertness, comprehension) | 11 | 1 |

| When Confused (e.g., on awakening, night only) | 9 | 3 |

| When Anxious (e.g., daily) | 7 | 5 |

| Depression screening (PHQ2) | 8 | 4 |

| Cognitive, Behavioral, Psychiatric Symptoms (e.g., impaired memory, inability to perform usual ADLs) | 12 | 0 |

| Disruptive Behavior Symptoms frequency of (e.g., once a month, daily) | 10 | 2 |

| Grooming ability (e.g., dependent on others) | 10 | 2 |

| Ability to dress | 11 | 1 |

| Toilet transferring (e.g., bedside commode, bedpan) | 12 | 0 |

| Toilet hygiene (e.g., dependent on others) | 12 | 0 |

| Transferring (bed to chair, bed bound) | 12 | 0 |

| Ambulation/Locomotion (e.g., requires cane, can wheel self in wheelchair) | 11 | 1 |

| Ability to Feed self (e.g., dependent on others) | 12 | 0 |

| Clinically significant medication issues? | 12 | 0 |

| Patient/Caregiver high-risk drug education needed | 8 | 4 |

| Oral medications: Able to prepare/take reliably/safely | 12 | 0 |

| Injectable medications: Able to prepare/take reliably/safely | 10 | 2 |

| Types/Sources of assistance at home | 11 | 1 |

| Self Care ability prior to current illness (e.g., needed help; dependent on others) | 10 | 2 |

| Mobility prior to current illness (e.g., needed help; dependent on others) | 10 | 2 |

| Stairs ability prior to current illness (e.g., needed help; dependent on others) | 10 | 2 |

| Functional cognition ability prior to current illness (e.g., needed help; dependent on others) | 10 | 2 |

| Device use prior to current illness (e.g., walker, wheelchair) | 10 | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sockolow, P.; Chou, E.Y.; Park, S. Addressing the Gap in Data Communication from Home Health Care to Primary Care during Care Transitions: Completeness of an Interoperability Data Standard. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071295

Sockolow P, Chou EY, Park S. Addressing the Gap in Data Communication from Home Health Care to Primary Care during Care Transitions: Completeness of an Interoperability Data Standard. Healthcare. 2022; 10(7):1295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071295

Chicago/Turabian StyleSockolow, Paulina, Edgar Y. Chou, and Subin Park. 2022. "Addressing the Gap in Data Communication from Home Health Care to Primary Care during Care Transitions: Completeness of an Interoperability Data Standard" Healthcare 10, no. 7: 1295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071295

APA StyleSockolow, P., Chou, E. Y., & Park, S. (2022). Addressing the Gap in Data Communication from Home Health Care to Primary Care during Care Transitions: Completeness of an Interoperability Data Standard. Healthcare, 10(7), 1295. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071295