Malpractice Claims and Ethical Issues in Prison Health Care Related to Consent and Confidentiality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Malpractice Claims in Prison Health Care

3. Consent and Confidentiality in Prison Health Care

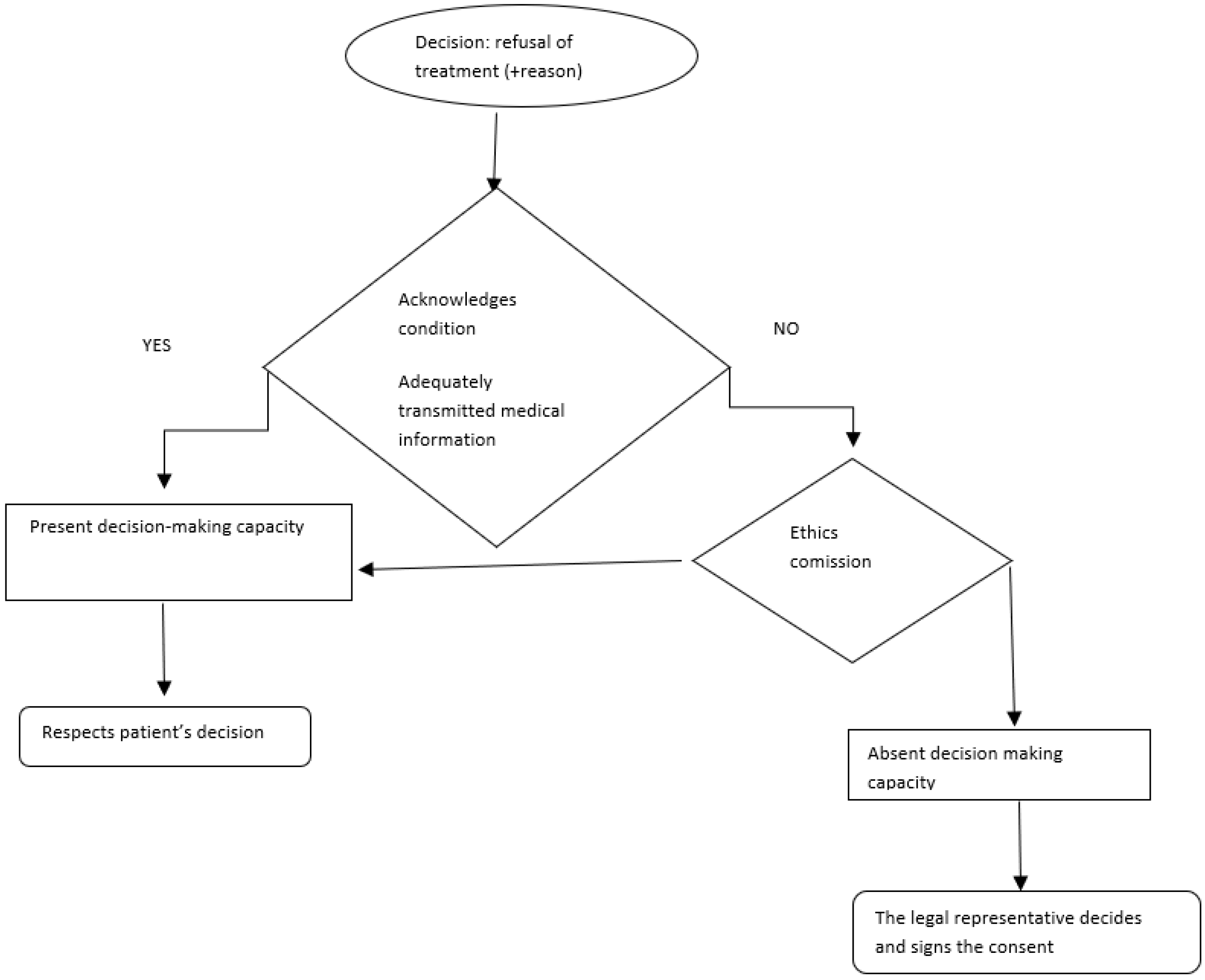

3.1. Informed Consent

3.2. Confidentiality

4. Particular Scenarios Physician–Inmate Patient

4.1. Hunger Strike

4.2. Consecutive to Acts of Violence

4.3. HIV Infection

4.4. Other Contagious Diseases

4.5. Drug Use

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lyons, B. Medical manslaughter. Ir. Med. J. 2013, 106, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferner, R.E.; McDowell, S.E. Doctors charged with manslaughter in the course of medical practice, 1795–2005: A literature review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2006, 99, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dermengiu, D.; Hostiuc, S.; Simionescu, M.; Marcus, I.; Asavei, V.; Gherghe, E.-V.; Badila, E. Is a full-fledged informed consent viable in prison environments? Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2015, 23, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Principles of Medical Ethics Relevant to the Role of Health Personnel, Particularly Physicians, in the Protection of Prisoners and Detainees against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. 1982. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/principles-medical-ethics-relevant-role-health-personnel (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Kelk, C. Recommendation No. R (98) 7 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States Concerning the Ethical and Organisational Aspects of Health Care in Prison. Eur. J. Health Law 1999, 6, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Prisons and Health; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014.

- Pazart, L.; Godard-Marceau, A.; Chassagne, A.; Vivot-Pugin, A.; Cretin, E.; Amzallag, E.; Aubry, R. Prevalence and characteristics of prisoners requiring end-of-life care: A prospective national survey. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgon, G.; Guiterrez, L. The Importance of Building Good Relationships in Community Corrections: Evidence, Theory and Practice of the Therapeutic Alliance BT—What Works in Offender Compliance: International Perspectives and Evidence-Based Practice; Ugwudike, P., Raynor, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 256–275. [Google Scholar]

- Bolcato, M.; Fiore, V.; Casella, F.; Babudieri, S.; Lucania, L.; Di Mizio, G. Health in Prison: Does Penitentiary Medicine in Italy Still Exist? Healthcare 2021, 9, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Stimpson, A.; Hostick, T. Prison health care: A review of the literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2004, 41, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi-Guarnieri, D. Clinician Liability in Prescribing Antidepressants. Focus 2019, 17, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, L. Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: An ill-fated triad. Diagnosis 2017, 4, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, M.S.; Collins, S.C. Medical Malpractice in Correctional Facilities: State Tort Remedies for Inappropriate and Inadequate Health Care Administered to Prisoners. Prison J. 2004, 84, 505–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.; Rishabh, M.; Ezaldein, H.H.; Bordeaux, J.S.; Jeffrey, S. Prison malpractice litigation involving dermatologists: A cross-sectional analysis of dermatologic medical malpractice cases involving incarcerated patients during 1970–2018. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 1019–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeng, F.; Bonnell, A.C.; O’Neil, E.C.; Mehran, N.A.; Kolomeyer, N.N.; Brucker, A.J.; Kolomeyer, A.M. Vision-Related Malpractice Involving Prisoners: Analysis of the Westlaw Database. Retina 2022, 42, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Li, D.; Li, C.; Yuwen, P.; Hou, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y. Characteristics of the medical malpractice cases against orthopedists in China between 2016 and 2017. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AMA Code of Medical Ethics: Consent, Communication & Decision Making. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/code-medical-ethics-consent-communication-decision-making (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Isailă, O.-M.; Hostiuc, S.; Teodor, M.; Curcă, G.-C. Particularities of Offenders Imprisoned for Domestic Violence from Social and Psychiatric Medical-Legal Perspectives. Medicina 2021, 57, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, J.E.; Emanuel, L.L. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA, J. Am. Med. 1992, 267, 2221–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostin, L.O.; Vanchieri, C.; Pope, A. (Eds.) Ethical Considerations for Research Involving Prisoners; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Haney, C. Mental Health Issues in Long-Term Solitary and “Supermax” Confinement. Crime Delinq. 2003, 49, 124–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R. Assessment of Mental Capacity: Guidance for Doctors and Lawyers (2nd edn) By The British Medical Association and The Law Society; BMJ Books: London, UK, 2004; 260p, ISBN 0 7279 16718. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 185, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irealand Department of Health. Seeking Consent: Working with People in Prison. 2002. Available online: https://bulger.co.uk/prison/seekingconsentinprison.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Appelbaum, P.S. Assessment of Patients’ Competence to Consent to Treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1834–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostiuc, S. Consimţământul Informat; Casa Cărții de Știință: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, P.S. Privacy in psychiatric treatment: Threats and responses. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elger, B.S.; Handtke, V.; Wangmo, T. Informing patients about limits to confidentiality: A qualitative study in prisons. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2015, 41, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Moskop, J.C.; Marco, C.A.; Larkin, G.L.; Geiderman, J.M.; Derse, A.R. From Hippocrates to HIPAA: Privacy and confidentiality in emergency medicine--Part I: Conceptual, moral, and legal foundations. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2005, 45, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, W.T. (Ed.) Oath of Hippocrates; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 5, p. 2632. [Google Scholar]

- Augestad, L.B.; Levander, S. Personality, health and job stress among employees in a Norwegian penitentiary and in a maximum security hospital. Work Stress 1992, 6, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, J.; Stöver, H.; Wolff, H. Dual loyalty in prison health care. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostiuc, S. Tratat de Bioetică Medicală și Stomatologică; C.H. Beck: Bucuresti, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Elger, B.S.; Handtke, V.; Wangmo, T. Paternalistic breaches of confidentiality in prison: Mental health professionals’ attitudes and justifications. J. Med. Ethics 2015, 41, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcă, G.C. Elemente de Etică Medicală. Norme de etică în Practica Medicală. Despre Principiile Bioeticii; Casa Cărții de Știință: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- García-Guerrero, J. La huelga de hambre en el ámbito penitenciario: Aspectos éticos, deontológicos y legales. Rev. Española Sanid. Penit. 2013, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Malta on Hunger Strikers, Adopted by the 43rd World Medical Assembly, St. Julians, Malta, November 1991 and Editorially Revised by the 44th World Medical Assembly, Marbella, Spain, September 1992 and Revised by the 57th WMA General Assem. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-malta-on-hunger-strikers/ (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Barilan, Y.M. The Role of Doctors in Hunger Strikes. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2017, 27, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euopean Court of Human Rights Guide on the Case-Law of the European Convention on Human Rights-Prisoners’ Rights. Available online: https://echr.coe.int/Documents/Guide_Prisoners_rights_ENG.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Wolff, N.; Blitz, C.L.; Shi, J.; Bachman, R.; Siegel, J.A. Sexual violence inside prisons: Rates of victimization. J. Urban Health 2006, 83, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.L. Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1992, 5, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.W.; Liebling, A.; Tait, S. The Relationships of Prison Climate to Health Service in Correctional Environments: Inmate Health Care Measurement, Satisfaction and Access in Prisons. Howard J. Crim. Justice 2011, 50, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, B.; Wilson, G. Prison Inmates’ Views of Whether Reporting Rape Is the Same as Snitching: An Exploratory Study and Research Agenda. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 28, 1201–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIV Testing and Counselling in Prisons and Other Closed Settings: Technical Paper. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. 3, HIV Testing and Counselling for Prisoners. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305394/ (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Vella, R.; Giuga, G.; Piizzi, G.; Alunni Fegatelli, D.; Petroni, G.; Tavone, A.M.; Potenza, S.; Cammarano, A.; Mandarelli, G.; Marella, G.L. Health Management in Italian Prisons during COVID-19 Outbreak: A Focus on the Second and Third Wave. Healthcare 2022, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, A.M.; Maiese, A.; Izzo, C.; Maiese, A.; Ametrano, M.; De Matteis, A.; Attianese, M.R.; Busato, G.; Caruso, R.; Cestari, M.; et al. COVID-19 Risk Management and Screening in the Penitentiary Facilities of the Salerno Province in Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allhoff, F. Dual-Loyalty and Human Rights in Health Professional Practice: Proposed Guidelines and Institutional Mechanisms BT—Physicians at War: The Dual-Loyalties Challenge; Allhoff, F., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 and Mandatory Vaccination: Ethical Considerations. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Policy-brief-Mandatory-vaccination-2022.1 (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Giubilini, A.; Douglas, T.; Savulescu, J. The moral obligation to be vaccinated: Utilitarianism, contractualism, and collective easy rescue. Med. Health Care. Philos. 2018, 21, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, C.; Monica, A.; De Matteis, G.; De Biasi, S.; De Chiara, A.; Pagano, A.M.; Mezzetti, E.; Del Duca, F.; Manetti, A.C.; La Russa, R.; et al. Not Only COVID-19: Prevalence and Management of Latent Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection in Three Penitentiary Facilities in Southern Italy. Healthcare 2022, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akolo, C.; Adetifa, I.; Shepperd, S.; Volmink, J. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2010, CD000171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolind, T.; Duke, K. Drugs in prisons: Exploring use, control, treatment and policy. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2016, 23, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Baan, F.C.; Montanari, L.; Royuela, L.; Lemmens, P.H.H.M. Prevalence of illicit drug use before imprisonment in Europe: Results from a comprehensive literature review. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2022, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; McNair, L. Ethical Issues in Research Involving Participants With Opioid Use Disorder. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2018, 52, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Checking Nutrition Status and Hygiene | |

| Following acts of violence | Suicide, attempted suicide, self-harm Physical altercations between inmates Psychological violence: threats, bullying, humiliation Sexual assault among inmates or sexual assault committed by correctional officers or other prison staff Torture or ill-treatment applied to inmates by correctional officers or other prison staff Isolated acts of violence or general acts of violence (riots) of inmates on prison staff |

| Communicable diseases | HIV, hepatitis, tuberculosis Influenza, measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria Sexually-transmitted infections Ectoparasites |

| Noncommunicable diseases | Cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases |

| Unhealthy behavior/risk factors | Smoking, alcohol use, drug use, inadequate physical activity, inadequate diet |

| Mental health problems | Anxiety disorder, depression, phobia, eating disorders |

| Oral health problems | Dental stomatitis, dental decay, dental erosions, maxillo-facial fractures |

| Aspect and behaviors | Agitated patient Mood disorders Cognitive disorders |

| Speech | Silent patient—can suggest depression Tangential, high-speed speech—can suggest hypomania |

| Mood | Depression and hypomania—distort the perception of the future Emotional instability—patients who have difficulty choosing a certain treatment |

| Thoughts and perception | Perception disorders (illusions, hallucinations) or overstated ideas lead to alteration of decision-making capacity |

| Cognition | Attention and concentration disorders Distraction |

| Memory | Cognitive disorders, memory disorders |

| Intelligence | Reduced intellectual abilities due to lack of education |

| Orientation in space and time | Cognitive disorders, disorders from substance use |

| Insight | Prior understanding of the presented medical issue |

| Duties to warn third parties of harm | Measures to warn a third party, depending on the level of the risk posed by the patient (and implicitly the risk of harm), in regard the danger represented by the patient |

| Duties to report various medical conditions | Infections with agents etiologically specific to bioterrorism (eg. anthrax, smallpox, plague, botulism, tularemia, viral hemorrhagic fevers) New epidemic diseases (eg. SARS-CoV 2 infection), the person’s capacity to operate vehicles Patients who are victims of domestic abuse (mainly minors and elderly persons) |

| Duties to inform legal guardians and other surrogates about the care of minors and other incompetent patients | Not applicable in the case of emancipated minors |

| Criminalistic evaluations |

| Disclosing the patient’s medical data to other persons without their consent |

| Assisting bodily searches |

| Assisting the collection of biological evidence (blood and urine) for security reasons |

| Supplying medical expertise measures to apply disciplinary measures Assisting/participating in physical constraint in the absence of medical criteria to warrant it |

| Assisting/participating in physical or capital punishment |

| Torture |

| Forced feeding |

| With the patient’s consent | Some information that may be used to the detriment of the patient must be considered and evaluated, an aspect that they may not understand or be aware of |

| Implicit | In dealing with other workers who need to provide the patient with adequate living conditions to protect their health (for example: the cook must know that the prisoner is allergic to a certain type of food) |

| Even if the patient did not agree | Strictly on the basis of the legislative framework |

| Without informing the patient | When the patient endangers the physician or a third party |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isailă, O.-M.; Hostiuc, S. Malpractice Claims and Ethical Issues in Prison Health Care Related to Consent and Confidentiality. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071290

Isailă O-M, Hostiuc S. Malpractice Claims and Ethical Issues in Prison Health Care Related to Consent and Confidentiality. Healthcare. 2022; 10(7):1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071290

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsailă, Oana-Maria, and Sorin Hostiuc. 2022. "Malpractice Claims and Ethical Issues in Prison Health Care Related to Consent and Confidentiality" Healthcare 10, no. 7: 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071290

APA StyleIsailă, O.-M., & Hostiuc, S. (2022). Malpractice Claims and Ethical Issues in Prison Health Care Related to Consent and Confidentiality. Healthcare, 10(7), 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071290