A Participatory Sensing Study to Understand the Problems Older Adults Faced in Developing Medication-Taking Habits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

2.3. Measurements

- Time-based consistency. We measured two relevant aspects:

- (i)

- Variance (S2) of the time of day, i.e., how the time of day of medication intake varied from one day to another; and

- (ii)

- Variance (S2) of time interval, i.e., whether the medication was taken leaving the appropriate time apart between episodes of the same group of medications, as per the prescribed frequency. Thus, lower variances would be better because the doses would be more evenly spread out, which would ensure that the level of medication in the individual’s system remains constant every day.

- Cue consistency. The cue consistency was estimated as a percentage of the number of times the activity set as a contextual cue by the older adults was reported as triggering the medication episode, divided by the number of days of the study duration (30 days).

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Initial Semi-Structured Interview

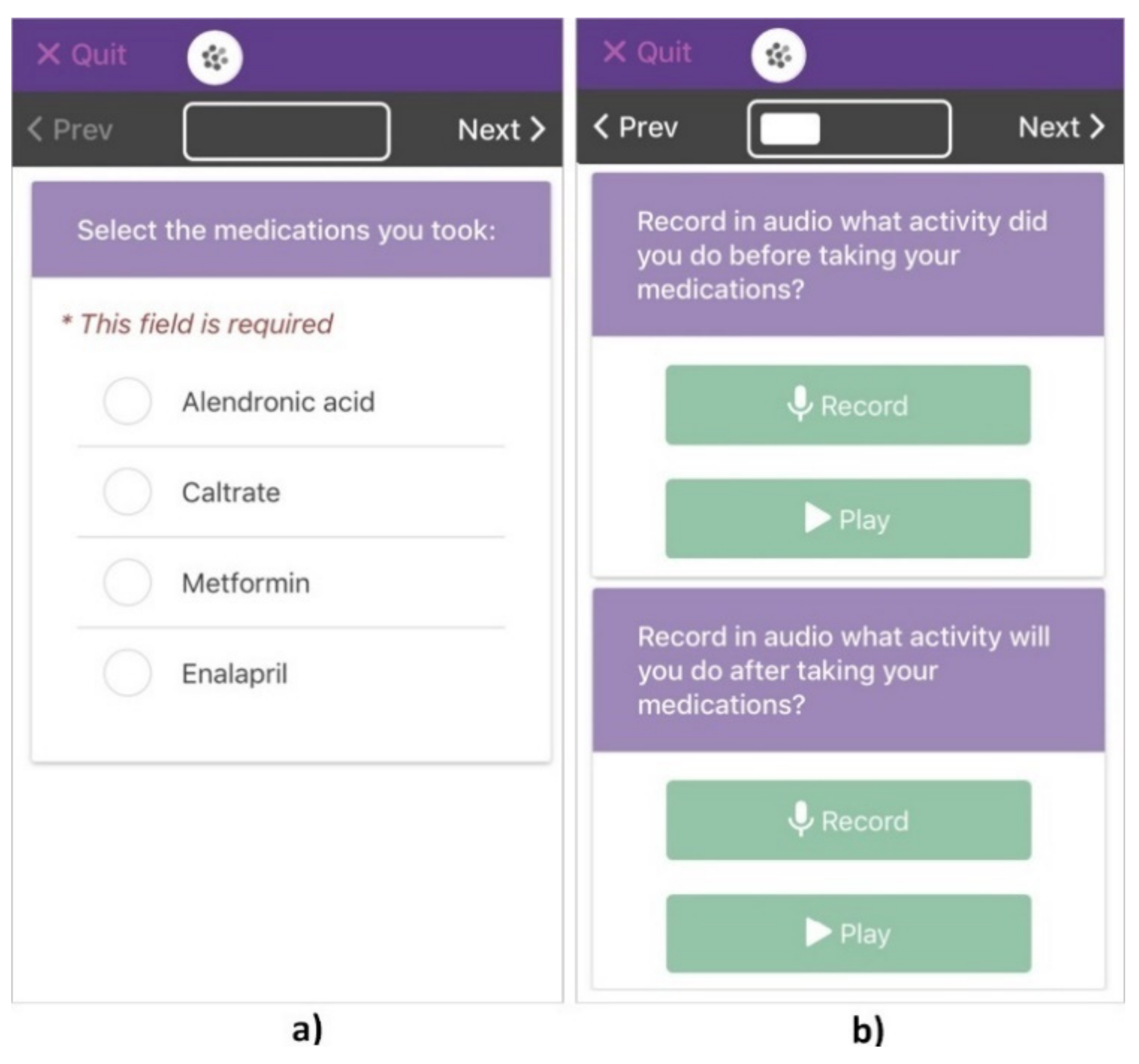

2.4.2. Participatory Sensing Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Setting and Participants

3.2. Medication Regimens and Routines

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1: How Does the Association That Older Adults Establish between Their Daily Routines and Their Medication Taking Enable Them to Perform It Consistently?

4.2. RQ2: What Problems Do Older Adults Face in Associating Their Daily Routines with Their Medication Taking?

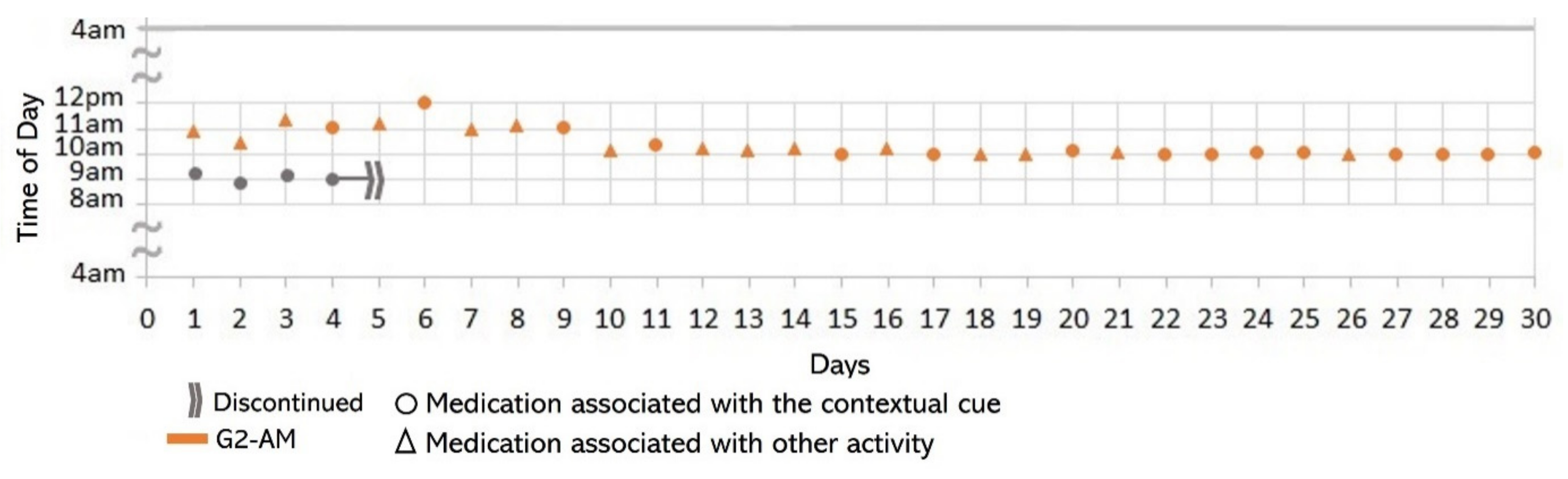

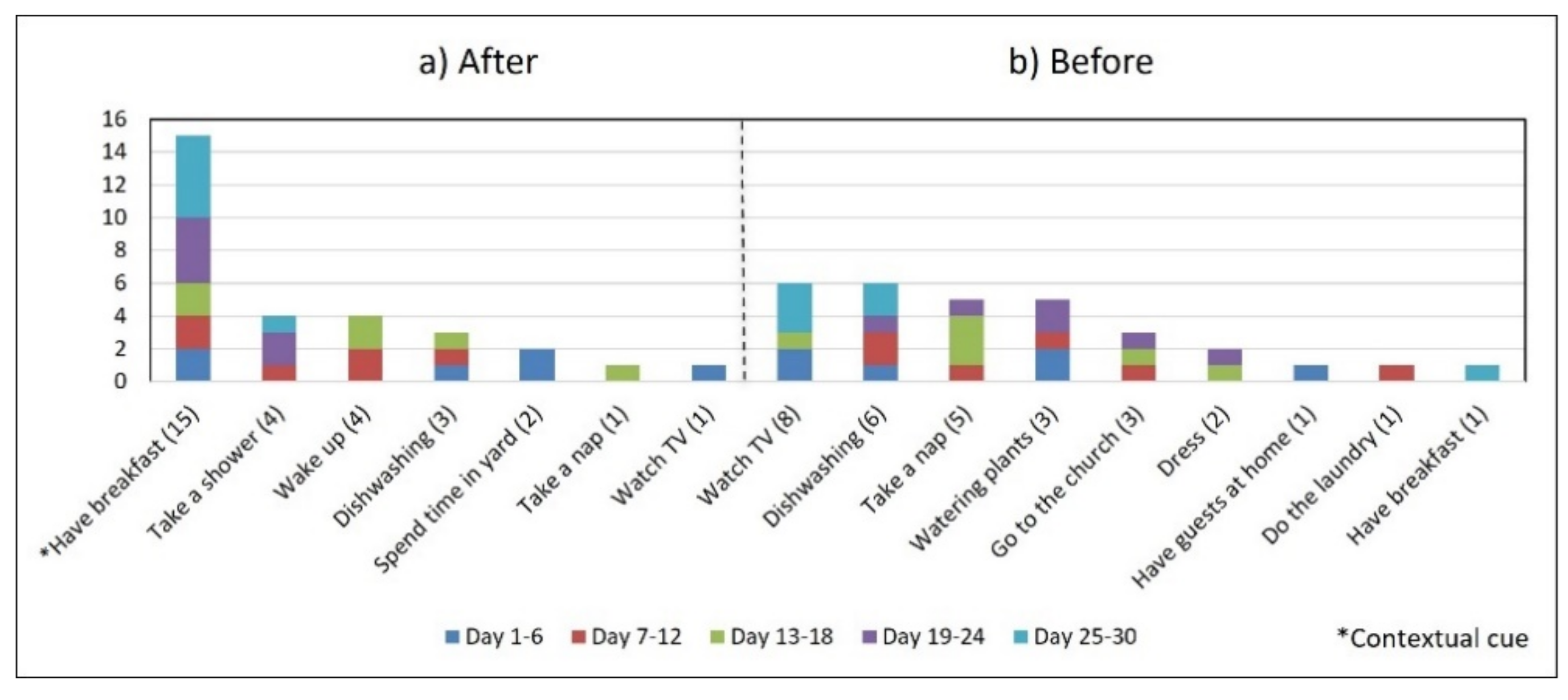

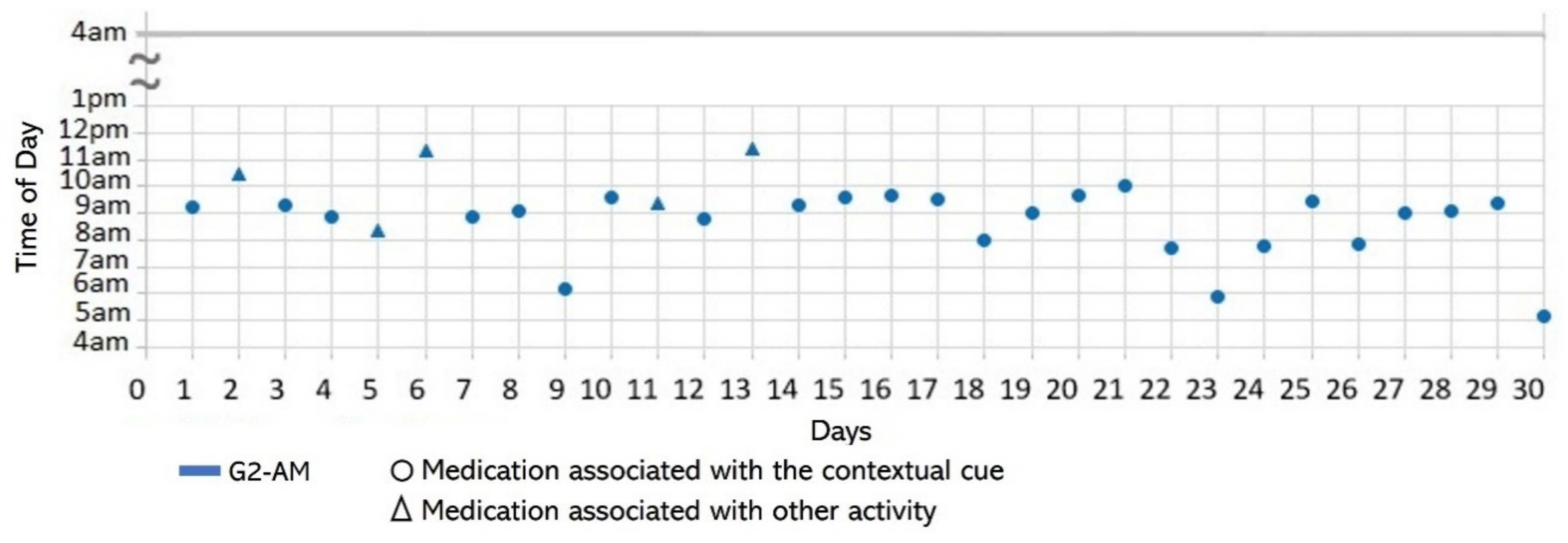

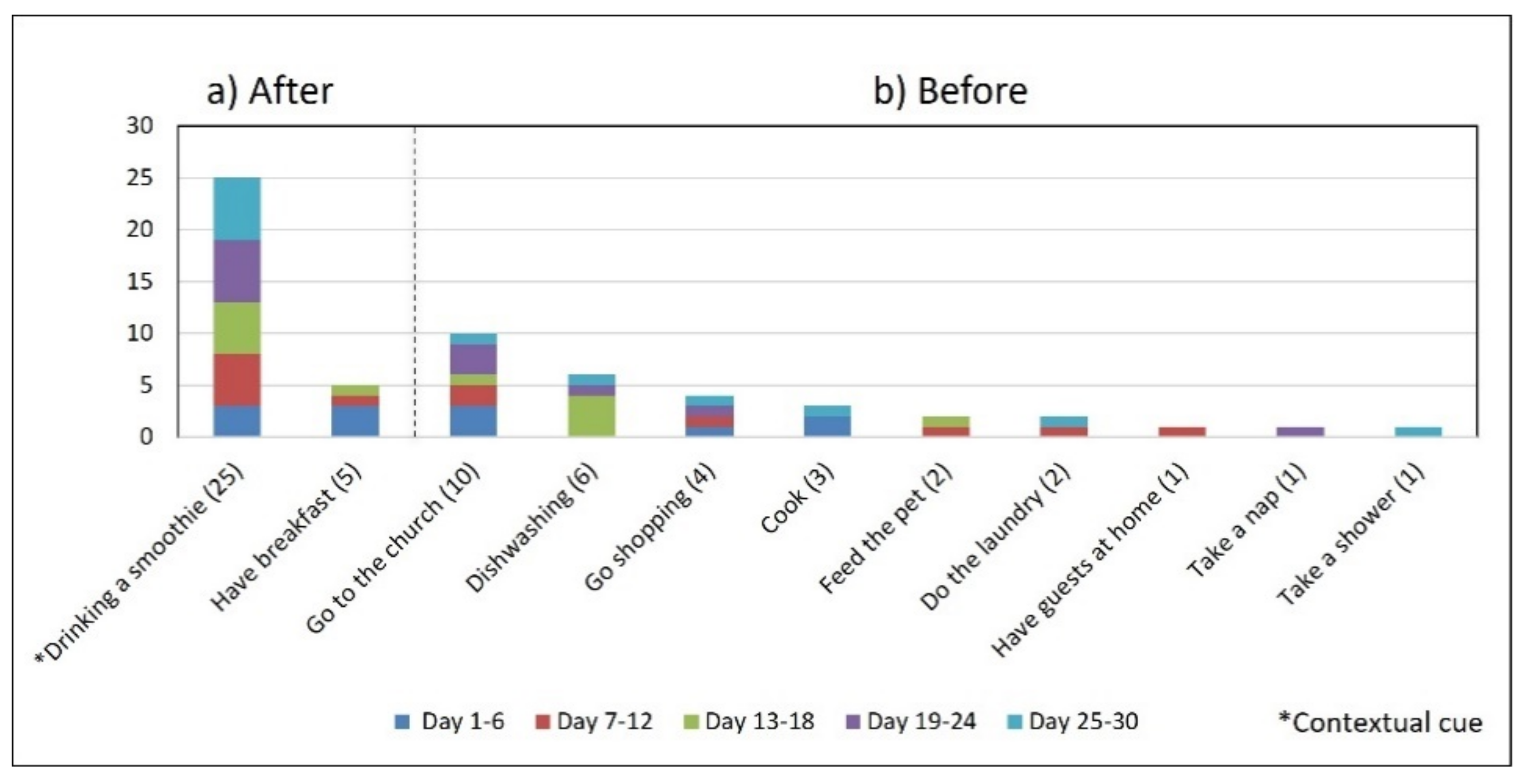

- Associating broad routines with medication-taking behaviors. We realize that some activities reported to be used as contextual cues belong to a broad daily routine. For some subjects, using a contextual cue that belongs to a broad routine was a restriction for taking the medication consistently. For instance, the contextual cue of S1 was having breakfast, which was part of a broad routine that included dishwashing. Thus, S1 reported for 6 days that the sequence of her activities was taking breakfast, taking G2 meds, and washing the dishes (see Figure 4). However, for the other 3 days, she took G2 after dishwashing, and on 2 of these days, the medication episodes were performed later than usual (see days 5 and 8 of Figure 3). These results suggest that various activities that comprise a broad routine may generate competition between them and dilute the contextual cue [17]. Therefore, the defined contextual cue lost intensity and could not be perceived. We also noticed that S1 did not habitually conduct this broad routine since she used the contextual cue 50% (15 days) of the time. The lack of evidence on adopting this broad routine as a contextual cue was due to mobility restrictions after her fall.

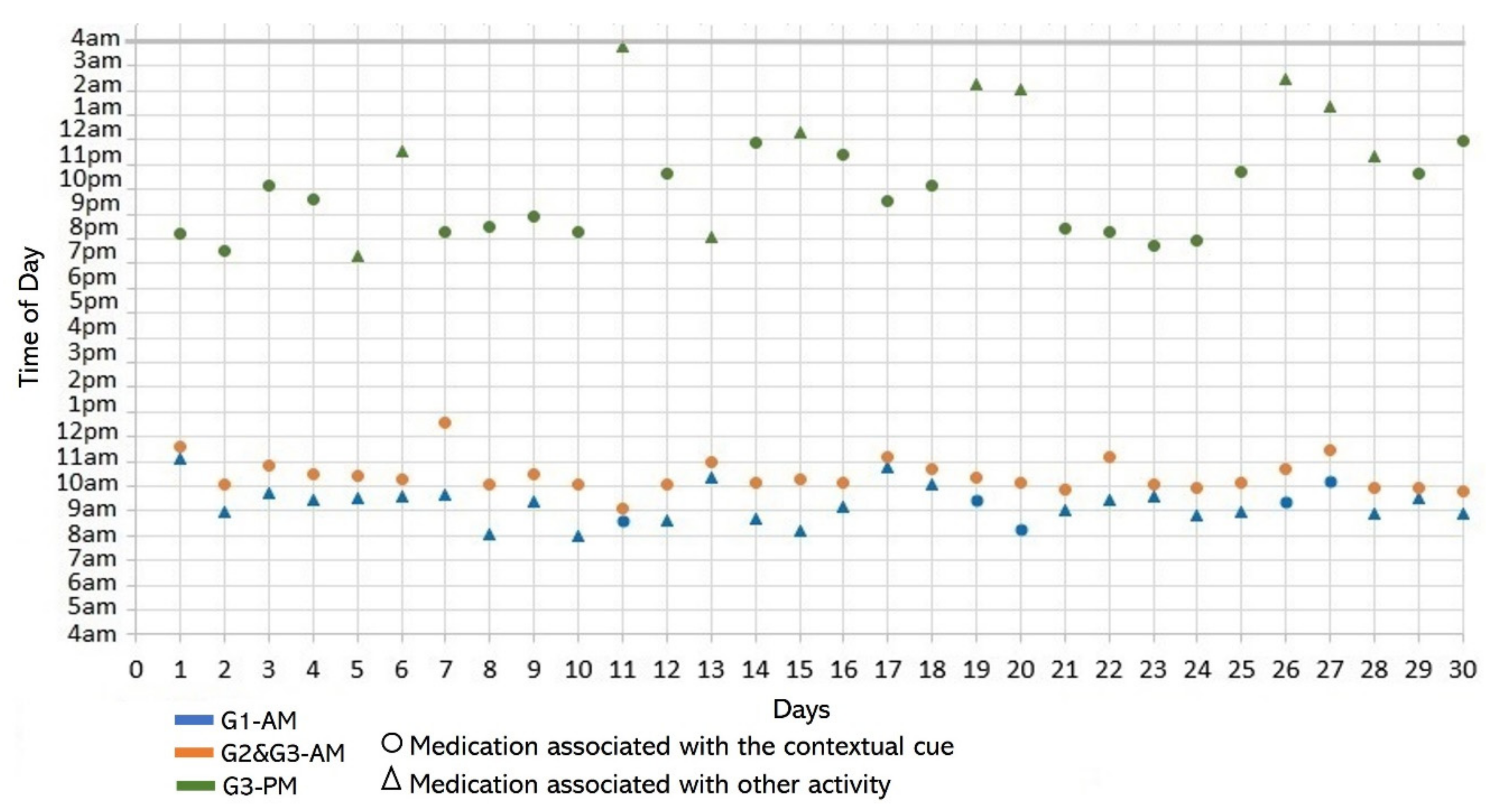

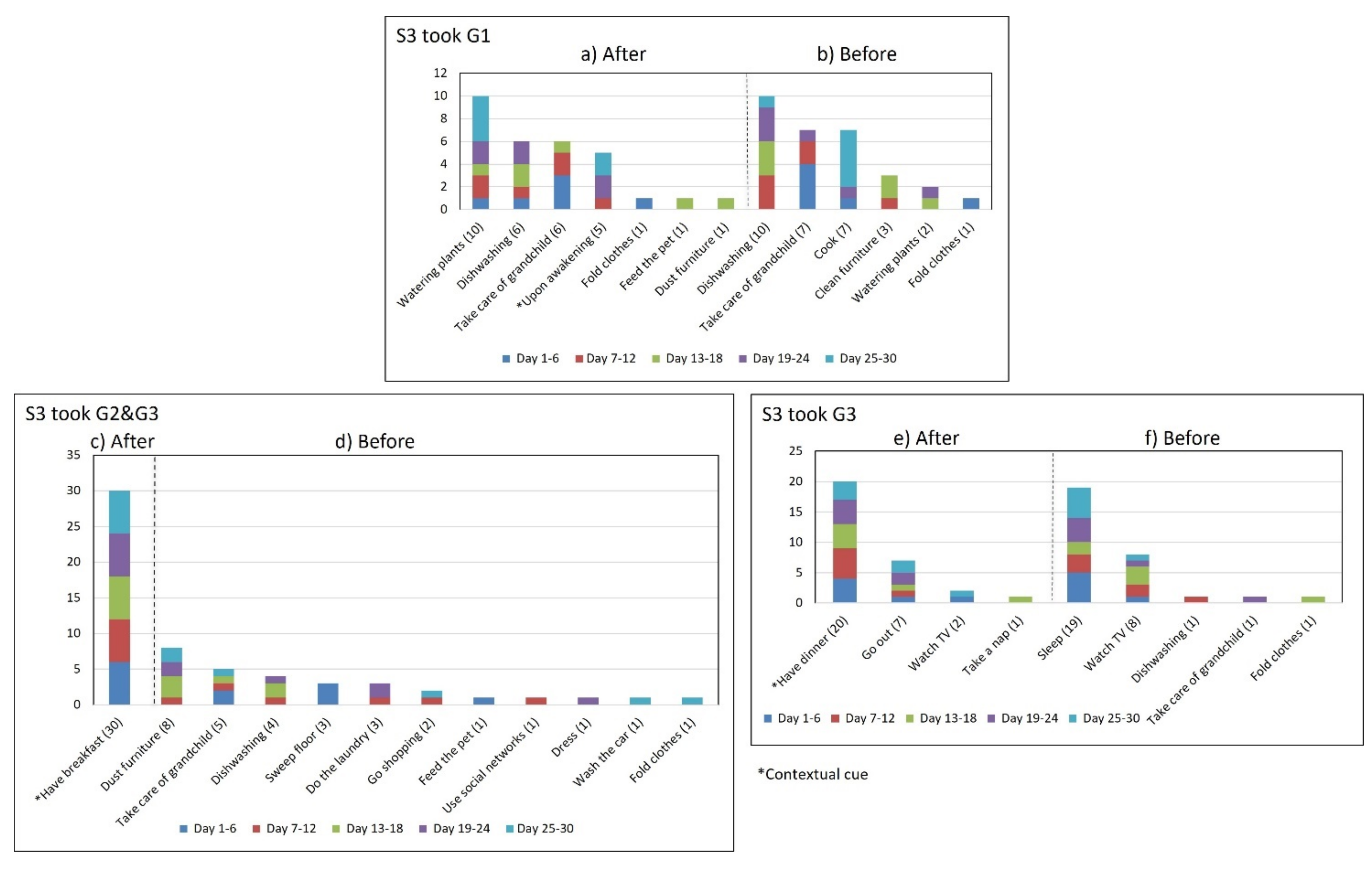

- Multiple daily routines are associated with a contextual cue. Some older adults associated numerous daily routines with a contextual cue. During the initial interview, S3 reported, “I take the medication [G1] in the morning, after waking up or a little later, because I have to take care of my grandchild, water my plants, and clean the kitchen.” The data collected during the study shows that she took G1 after waking up for 5 days (see Figure 8) and that she used to carry out different habitual routines, such as watering the plants (10 days), taking care of her grandson (6 days), and cleaning the kitchen (6 days). Unfortunately, associating multiple daily behaviors with the same contextual cue may reduce the probability that any of these behaviors become a habit [17].

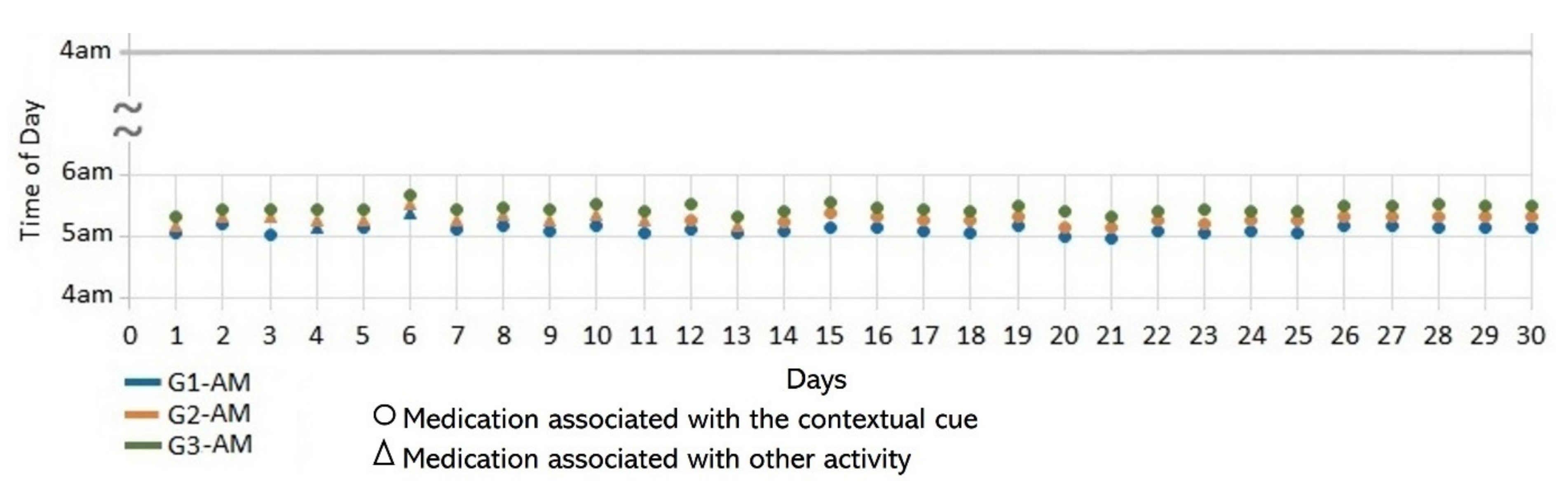

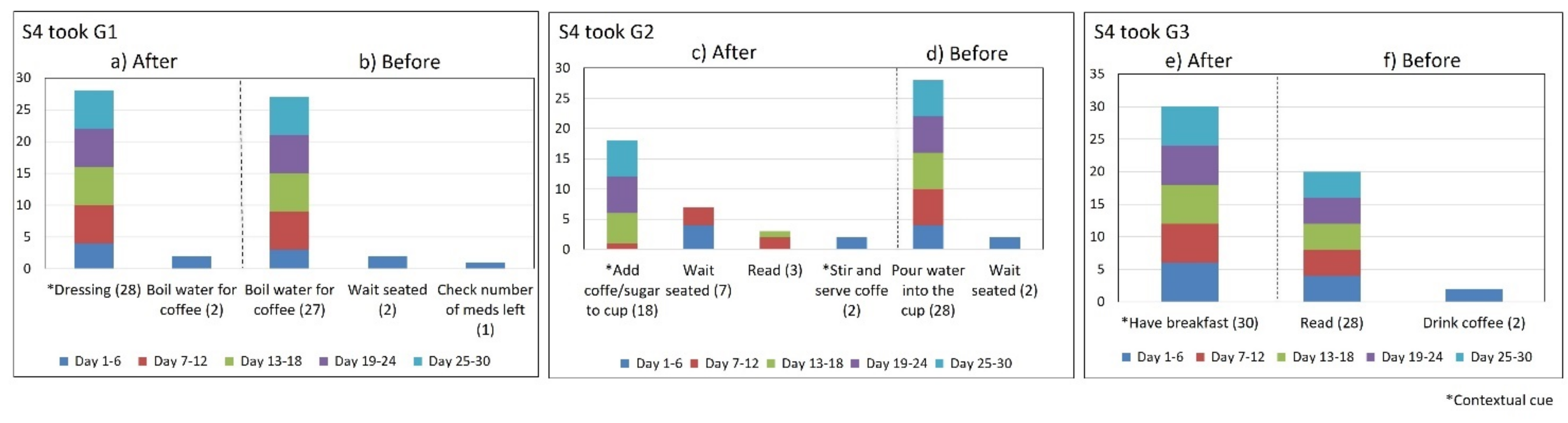

- Lack of strict routines. S4 had a habitual morning broad routine in which he integrated the medication episodes for taking G1, G2, and G3. They were accomplished consecutively in a short period (see Figure 9). His routine included waking up at 5:00 a.m., dressing, making instant coffee, reading the newspaper, and having breakfast (Figure 10, middle graph). He obtained a time-based consistent behavior for taking all the medications, even though he got a low rate for using “making coffee” as a contextual cue of G2 (66.6%). This is because G2 was associated with different tasks carried out in the middle of the broad routine, in contrast to G1 and G3, which were taken consistently after “dressing” (see Figure 10, left graph) and after “having breakfast” (see Figure 10, right graph) respectively. We conclude that S4′s medication behavior was characterized by a rule-based process he established and followed. It included a sequence of daily activities and medications alternated at specific intervals and carried out in the same place (dining table).

- Disruption of daily routines. Previous studies demonstrated that older adults recognized that facing unexpected or unplanned activities delays performing medication taking, and they were more likely to forget it [25,27,28]. In contrast to these studies, we found that when older adults plan to engage in activities that disrupt their daily routine, they displace the activity that acts as a contextual cue, thus displacing medication intake. For example, S2 said during the initial interview: “when I go shopping, I take the morning medication [G1] earlier or later than usual...”. The data we collected confirmed this behavior, as she reported getting up earlier than usual to go shopping on 4 days (2, 9, 23, and 30, shown in Figure 5). However, on most of these days (9, 23, and 30), she also performed the activity established as a contextual cue before going shopping and then took the medication, which affected its time-based consistency. Similarly, S3 reported carrying out the episode G3-PM with the contextual cue (after dinner) for 20 days (see Figure 8, right). On 7 days of these 20 days, she went out of her home and dined later than usual (days 6, 11, 15, 19, 20, 26, and 27), as shown in Figure 7. On other days she reported spending time doing different activities during the afternoon, e.g., “[on day 14] I was watching TV, and the time passed…” and “[on day 16] I fell asleep, and I didn’t realize the time,” which led her to have dinner later and to delay taking her medications.

4.3. Considerations for Designing Habit-Formation Interventions

4.3.1. Measuring for Habit Formulation and Awareness Provision

4.3.2. Educational Strategies to Acquire Medication Habits

4.3.3. Motivate through Natural Reinforcements

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO|Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Available online: https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_report/en/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Vrijens, F.; Van de Voorde, C.; Farfan-Portet, M.-I.; Stichele, R.V. Patient socioeconomic determinants for the choice of the cheapest molecule within a cluster: Evidence from Belgian prescription data. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2012, 13, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaschning, K.; Koerner, M.; Wirtz, M.A. Analyzing the effects of barriers to and facilitators of medication adherence among patients with cardiometabolic diseases: A structural equation modeling approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronish, I.M.; Thorpe, C.T.; Voils, C.I. Measuring the multiple domains of medication nonadherence: Findings from a Delphi survey of adherence experts. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkens, A.E.M.J.H.; Milosevic, V.; Van Der Kuy, P.H.M.; Damen-Hendriks, V.H.; Gonzalvo, C.M.; Hurkens, K.P.G.M. Medication-related hospital admissions and readmissions in older patients: An overview of literature. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glans, M.; Ekstam, A.K.; Jakobsson, U.; Bondesson, Å.; Midlöv, P. Medication-related hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge—A retrospective study of risk factors in older adults. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L.J.; Kelley, E.T.; Dhingra-Kumar, N.; Kieny, M.-P.; Sheikh, A. Medication Without Harm: WHO’s Third Global Patient Safety Challenge. Lancet 2017, 389, 1680–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.; English, J.; Knee, C.; Keller, A. Treatment Adherence in Integrative Medicine—Part One: Review of Literature. Integr. Med. A Clin. J. 2021, 20, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, A.J.; Elliott, R.A.; Petrie, K.; Kuruvilla, L.; George, J. Interventions for improving medication-taking ability and adherence in older adults prescribed multiple medications. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD012419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banning, M. A review of interventions used to improve adherence to medication in older people. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, V.S.; Ruppar, T.M. Medication adherence outcomes of 771 intervention trials: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; Gardner, B. Promoting habit formation. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013, 7, S137–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommel, B. GOALIATH: A theory of goal-directed behavior. Psychol. Res. 2022, 86, 1054–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, R.; Luszczynska, A. How to Overcome Health-Compromising Behaviors. Eur. Psychol. 2008, 13, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D.T.; Wood, W.; Labrecque, J.S.; Lally, P. How do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of habits in daily life. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Neal, D.T. A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 843–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbell, S.; Verplanken, B. The automatic component of habit in health behavior: Habit as cue-contingent automaticity. Health Psychol. 2010, 29, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; Wardle, J.; Gardner, B. Experiences of habit formation: A qualitative study. Psychol. Health Med. 2011, 16, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarz, K.; Gardner, B.; Cox, A.; Blandford, A. What influences the selection of contextual cues when starting a new routine behaviour? An exploratory study. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Lally, P. Modelling Habit Formation and Its Determinants. In The Psychology of Habit: Theory, Mechanisms, Change, and Contexts; Verplanken, B., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, K.C.; Einstein, G.O.; Morrow, D.G.; Hepworth, J.T. A multifaceted prospective memory intervention to improve medication adherence: Design of a randomized control trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2013, 34, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.A.; Rosenheck, R. Enhancing Medication Compliance for People with Serious Mental Illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1999, 187, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrijens, B.; Urquhart, J.; White, D. Electronically monitored dosing histories can be used to develop a medication-taking habit and manage patient adherence. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 7, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boron, J.B.; Rogers, W.A.; Fisk, A.D. Everyday memory strategies for medication adherence. Geriatr. Nurs. 2013, 34, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insel, K.C.; Einstein, G.O.; Morrow, D.G.; Koerner, K.M.; Hepworth, J.T.; Mph, K.M.K. Multifaceted Prospective Memory Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.J.; Van Oss, T. Using Daily Routines to Promote Medication Adherence in Older Adults. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 67, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarz, K.; Rodríguez, M.D.; Cox, A.; Blandford, A. Understanding the use of contextual cues: Design implications for medication adherence technologies that support remembering. Digit. Health 2016, 2, 2055207616678707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J. The Habitual Use of the Self-report Habit Index. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 43, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, P.-Y.; Bakken, S. Review of health information technology usability study methodologies. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2011, 19, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzblatt, K.; Wendell, J.B.; Wood, S. Contextual Design A How-To Guide to Key; Elsevier/Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N.S.; Norman, D.A.; Draper, S.W. User Centered System Design: New Perspectives on Human-Computer Interaction; L. Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claxton, A.J.; Cramer, J.; Pierce, C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin. Ther. 2001, 23, 1296–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimm, R.; Vandelanotte, C.; Rhodes, R.E.; Short, C.; Duncan, M.J.; Rebar, A.L. Cue Consistency Associated with Physical Activity Automaticity and Behavior. Behav. Med. 2016, 42, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicaksono, A.; Hendley, R.J.; Beale, R. Using Reinforced Implementation Intentions to Support Habit Formation. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epicollect5 API—Epicollect5 Data Collection API. Available online: https://developers.epicollect.net/ (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, O.; Weinman, J.; Jackson, S.H.D. Intentional Non-Adherence to Medications by Older Adults. Drugs Aging 2014, 31, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demonceau, J.; for the ABC project team; Ruppar, T.; Kristanto, P.; Hughes, D.A.; Fargher, E.; Kardas, P.; De Geest, S.; Dobbels, F.; Lewek, P.; et al. Identification and Assessment of Adherence-Enhancing Interventions in Studies Assessing Medication Adherence Through Electronically Compiled Drug Dosing Histories: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Drugs 2013, 73, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.L.; Dey, A.K. Real-time feedback for improving medication taking. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; pp. 2259–2268. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, R.; Cherubini, M.; Oliver, N. MoviPill: Improving medication compliance for elders using a mobile persuasive social game. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing (UbiComp), Copenhagen, Denmark, 26–29 September 2010; pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, S.; Kinmonth, A.-L.; Hardeman, W.; Hughes, D.; Boase, S.; Prevost, T.; Kellar, I.; Graffy, J.; Griffin, S.; Farmer, A. Does Electronic Monitoring Influence Adherence to Medication? Randomized Controlled Trial of Measurement Reactivity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 48, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.L.; Dey, A.K. Sensor-based observations of daily living for aging in place. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2015, 19, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.; Trifan, A.; Neves, A.J.R. Lifelog Retrieval from Daily Digital Data: Narrative Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e30517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.D.; Beltrán, J.; Valenzuela-Beltrán, M.; Cruz-Sandoval, D.; Favela, J. Assisting older adults with medication reminders through an audio-based activity recognition system. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2020, 25, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Lazar, A.; Findlater, L. Use of Intelligent Voice Assistants by Older Adults with Low Technology Use. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2020, 27, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarz, K.; Cox, A.L.; Blandford, A. Don’t Forget Your Pill! Designing Effective Medication Reminder Apps That Support Users’ Daily Routines. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stawarz, K.; Cox, A.L.; Blandford, A. Beyond self-tracking and reminders: Designing smartphone apps that support habit formation. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; Volume 2015, pp. 2653–2662. [Google Scholar]

- Staddon, J.E.R.; Cerutti, D.T. Operant Conditioning. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Positive Reinforcement in Psychology (Definition + 5 Examples). Available online: https://positivepsychology.com/positive-reinforcement-psychology/ (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Wirtz, V.J.; Reich, M.R.; Flores, R.L.; Dreser, A. Medicines in Mexico, 1990–2004: Systematic review of research on access and use. Salud Publica Mex. 2008, 50, S470–S479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zárate-Bravo, E.; García-Vázquez, J.-P.; Torres-Cervantes, E.; Ponce, G.; Andrade, G.; Valenzuela-Beltrán, M.; Rodríguez, M.D. Supporting the Medication Adherence of Older Mexican Adults Through External Cues Provided with Ambient Displays: Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e14680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | Age | Gender | Diseases | Group of Meds (N) | Episode Time | Contextual Cue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 70 | Female | Cholesterol, Hypertension | G1 (1) | AM ≈ 8:00 | Upon awakening |

| G2 (1) | AM ≈ 10:00 | After breakfast | ||||

| S2 | 72 | Female | Hypertension, Diabetes, Gastritis | G1 (4) | AM ≈ 8:30 | After drinking a smoothie |

| S3 | 72 | Female | Hypertension, Diabetes, Osteoporosis, Heart disease | G1 (1) | AM ≈ 8:00 | Upon awakening |

| G2 (1) | AM ≈ 9:00 | After breakfast | ||||

| G3 (2) | AM ≈ 9:00 | After breakfast | ||||

| PM ≈ 19:00 | After dinner | |||||

| S4 | 73 | Male | Hypertension, Diabetes, Thyroid. Angina pectoris | G1 (1) | AM ≈ 5:00 | After dressing |

| G2 (2) | AM ≈ 5:15 | When making coffee | ||||

| G3 (3) | AM ≈ 5:30 | After breakfast |

| Subjects | Medication Episodes | Cue Consistency | Time Interval (h) | Time of Day (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md | SDe | S2f | Md | SDe | S2f | ||||

| S1 | G2 a-AM | 50% | 23.97 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 10.39 | 0.54 | 0.29 | |

| S2 | G1 a-AM | 83% | 23.86 | 1.82 | 3.30 | 8.90 | 1.39 | 1.94 | |

| S3 | G1 a-AM | 17% | 23.92 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.28 | 0.75 | 0.56 | |

| G2 a-AM c | 100% | 23.94 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 10.43 a | 0.67 a | 0.45 a | ||

| G3 b- | AMc | 11.90 b | 2.17 b | 4.72 b | |||||

| PM | 66.6% | 22.38 | 2.35 | 5.54 | |||||

| S4 | G1 a-AM | 93% | 24.00 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 5.12 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| G2 a-AM | 60% | 24.01 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 5.28 | 0.07 | 0.01 | ||

| G3 a-AM | 100% | 24.01 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 5.45 | 0.07 | 0.01 | ||

| Subject | ID | Gender | Age (Years) | Living with: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Female | 70 | Her Daughter and Grandchildren | ||||

| Medication characteristics | Health problem | Prescriptiona,c | Reported cues used to take the medication | ||||

| Medication | Doses (pills) | Daily frequency | Time | Associated activity | bMed episodes | ||

| Cholesterol | Pravastatin | 1 | 24 h | ≈8:00 | Upon awakening | G1-AM | |

| Hypertension | Amlodipine | 1 | 24 h | ≈10:00–10:30 | After breakfast | G2-AM | |

| Fluid retention | Chlortalidone | 1 | 24 h | ≈12:00 | Watering plants | n/m | |

| Pain | Indomethacin | 1 | 24 h | ≈14:00 | Before watching favorite TV-show | n/m | |

| Pain | Tramadol | 1 | 24 h | ≈16:00 | Before watching favorite soup opera | n/m | |

| Depression | Mirtazapine | 1 | 24 h | ≈20:00–22:00 | Before sleeping | n/m | |

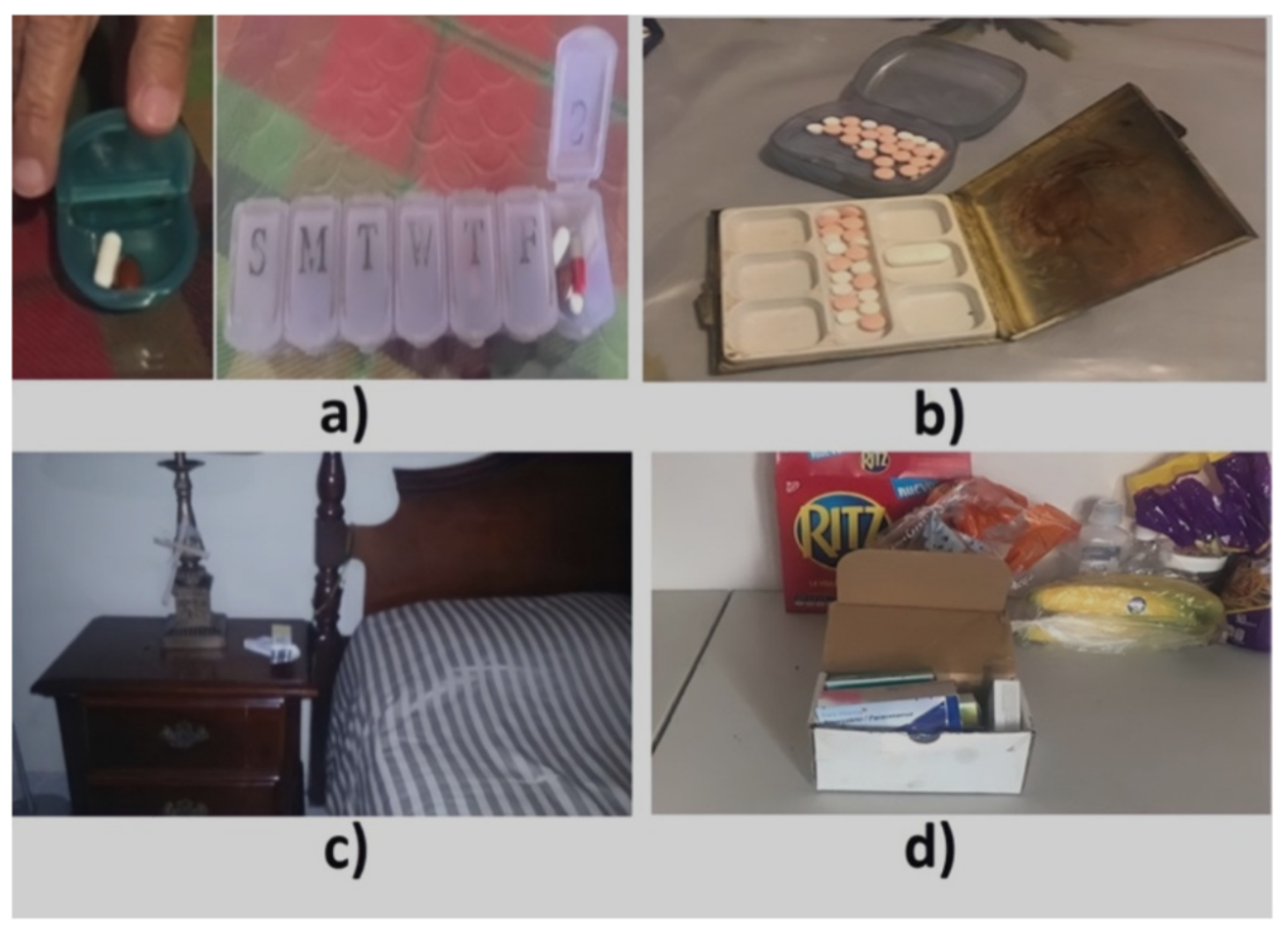

| Routine description | “I kept notes of the time I took the medication for a long time until I learned how to do it, and I don’t forget to take the pills. I have two pill boxes, a weekly one and a smaller one [with one compartment] to store the pills to take during the day. Sunday, I go to the weekly pill box, separate the pills, and add them to the seven compartments of the pill box [one for each day]. Every night I put the pills for the next day into the small pillbox [with one compartment]; I distinguish the pills by their size and color… As soon as I wake up, I get up and take the pravastatin that controls the cholesterol. I have the pill box on the nightstand in the bedroom, near a glass of water. Then, I go to the kitchen, make coffee, eat some toast, go back to my room, make the bed, clean the room a bit, and sometimes watch TV. Between 10:00 a.m. and 10:30 a.m., I have breakfast and take the amlodipine pill to control blood pressure. If I don’t leave the house, I watch television or go out to the patio to water the plants. I take the following medicine, chlorthalidone, right away, I have lunch, and I start to watch my favorite program, which is at 2:00 p.m., just when I take the next drug, the indomethacin. At 4:00 p.m., the soap opera that I like starts, which indicates me to take the following drug, tramadol. After 5:00 p.m., I take a nap, and between 8:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m., I take the last medicine before I go to sleep.” | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valenzuela-Beltrán, M.; Andrade, Á.G.; Stawarz, K.; Rodríguez, M.D. A Participatory Sensing Study to Understand the Problems Older Adults Faced in Developing Medication-Taking Habits. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071238

Valenzuela-Beltrán M, Andrade ÁG, Stawarz K, Rodríguez MD. A Participatory Sensing Study to Understand the Problems Older Adults Faced in Developing Medication-Taking Habits. Healthcare. 2022; 10(7):1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071238

Chicago/Turabian StyleValenzuela-Beltrán, Maribel, Ángel G. Andrade, Katarzyna Stawarz, and Marcela D. Rodríguez. 2022. "A Participatory Sensing Study to Understand the Problems Older Adults Faced in Developing Medication-Taking Habits" Healthcare 10, no. 7: 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071238

APA StyleValenzuela-Beltrán, M., Andrade, Á. G., Stawarz, K., & Rodríguez, M. D. (2022). A Participatory Sensing Study to Understand the Problems Older Adults Faced in Developing Medication-Taking Habits. Healthcare, 10(7), 1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071238