Child Gender and Married Women’s Overwork: Evidence from Rural–Urban Migrants in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Concept Definition and Variable Selection

- (1)

- Migrant women. Migrant women mainly refer to rural–urban migrants. Based on the questionnaire, married migrant women are those: (1) with their marital status as married; (2) aged 20–59; (3) moved from rural areas to urban areas; (4) with children under the age of 18.

- (2)

- Overwork. This is the dependent variable used to reflect the greatest risk factor of work-related disease burden, defined by long working hours. Referring to the health burden report released by the WHO and the ILO, people who work for more than 55 h have an increased risk of stroke and death due to ischemic heart disease, compared with those who work 35–40 h a week [17]. This paper defined overwork by using the weekly working time of no less than 55 h. The working hour was measured by two survey questions: “Have you done paid work for more than one hour before May Day?” and “How many hours have you worked this week?” Therefore, the migrant women can be divided into two categories: overtime workers (no less than 55 working hours) and nonovertime workers (less than 55 working hours).

- (3)

- Child gender. This is the independent variable, indicated by the child’s gender in the family. Based on their family size (number of children), migrant women are divided into two categories: one-child family and two-child family. For the one-child family, there are one-boy families and one-girl families (basic group), while the two-child family is divided into four groups based on the child’s gender and birth order: two-girl families (basic group), with the firstborn girl then boy family, the firstborn boy then girl family, and the two-boy family.

- (4)

- Childcare. This is one of the control variables, measured by the survey question: “Who is the primary caregiver of the child?” According to the original questionnaire, we defined the groups who are mainly taken care of by their mothers as 1, while those who answered that the main caregivers were fathers, grandparents, other relatives, neighbors and friends, teachers’ trusteeship, and unattended were assigned 0.

- (5)

- Medical insurance. This control variable pertained to the participation of employees’ medical insurance, which helps to describe the health security level of migrant women. In the questionnaire, this variable is measured by the question: “Do you participate in the medical insurance for urban employees?” We defined the samples who participated in medical insurance as 1, while those who did not participate the employee’s medical insurance as 0.

- (6)

- Labor contract. In the questionnaire, the nature of migrant women’s labor contract is divided into three types: (a) fixed term contract; (b) nonfixed term contract; and (c) no contract. In China, workers who sign the first two types of contracts are generally engaged in formal work, while those who do not sign contracts are generally engaged in informal work. Therefore, we defined the first two categories as 1 and those who did not sign a labor contract as 0.

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Variables

3.2. Birhthing Sons and Overwork of Migrant Women

3.3. Number of Sons and the Burden of Migrant Women’s Overwork

3.4. The Negative Effect of Overwork on Migrant Women’s Health Condition

4. Discussion

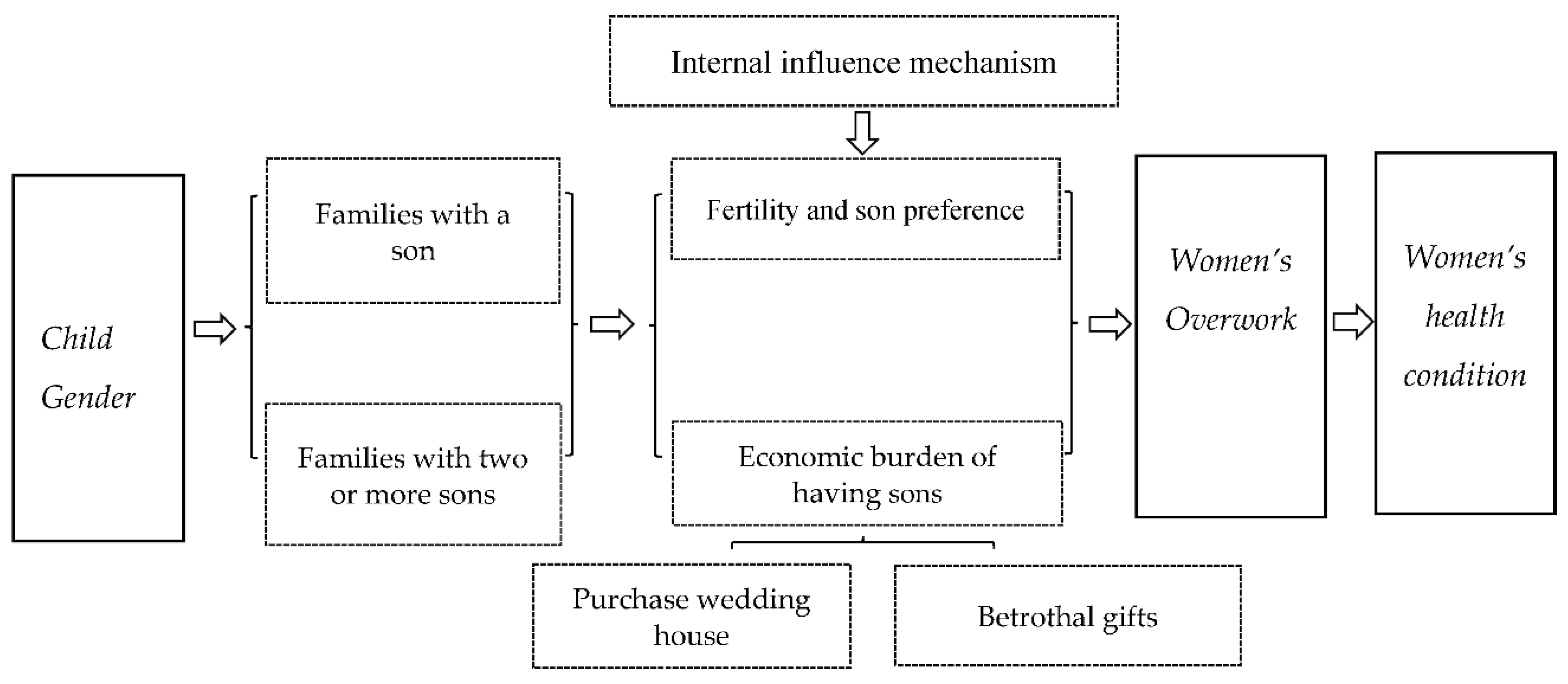

4.1. The Internal Mechanism of Child Gender and Women’s Overtime Work

4.1.1. Son Preference and Migrant Women’s Fertility Behavior

4.1.2. The Economic Burden of Having Boys and Migrant Women’s Overwork

4.2. Endogeneity and Robustness Test

4.2.1. Endogenous Problems

4.2.2. Having Sons and Overwork from the Perspective of Women’s Life Cycle

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bell, L.A.; Freeman, R.B. The incentive for working hard: Explaining hours worked differences in the US and Germany. Labour Econ. 2001, 8, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Tanaka, H. Overtime work, insufficient sleep, and risk of non-fatal acute myocardial infarction in Japanese men. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murat, A.; Mesut, K. Do immigrants work longer hours than natives in Europe? Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2019, 32, 1394–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Miranti, R.; Li, J. Working hours mismatch, job strain and mental health among mature age workers in Australia. J. Econ. Ageing 2020, 15, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garhammer, M. Pace of Life and Enjoyment of Life. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 217–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Ruiz, J. Comparing police overwork in China and the USA: An exploratory study of death from overwork (‘Karoshi’) in policing. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 14, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehata, T. Long working hours and occupational stress-related cardiovascular attacks among middle-aged workers in Japan. J. Hum. Ergol. 1991, 20, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.; Fried, Y.; Shirom, A. The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Yan, P.; Zeng, Y. Coresidence with elderly parents and female labor supply in China. Demogr. Res. 2016, 35, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buell, P.; Breslow, L. Mortality from coronary heart disease in California men who work long hours. J. Chron. Dis. 1960, 11, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.; Nijhuis, F.; Van Boxtel, M.; Knottnerus, J. Flexible work schedules and mental and physical health. A study of a working population with nontraditional working hours. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, C.; Etoh, R.; Honda, D.; Fujii, R.; Sasaki, N.; Kawase, Y.; Tsutsui, T.; Horie, S. Association of overtime-work hours with lifestyle and mental health status. Int. Congr. Ser. 2006, 1294, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kuroda, S.; Owan, H. Mental health effects of long work hours, night and weekend work, and short rest periods. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 246, 112774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijters, P.; Johnston, D.; Meng, X. The Mental Health Cost of Long Working Hours: The Case of Rural Chinese Migrants; Working Paper; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The association between long working hours and health: A systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, K.; Takahashi, M.; Nakata, A. Health Problems due to Long Working Hours in Japan: Working Hours, Workers’ Compensation (Karoshi), and Preventive Measures. Ind. Health 2006, 44, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cormier, Z. Having sons can shorten a woman’s life expectancy. Nature 2013, 12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Ji, Y.; Li, S. Effect of long working hours and insomnia on depressive symptoms among employees of Chinese internet companies. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-S.; Ki, M.; Kim, K.-H.; Ju, Y.-S.; Paek, D.; Lee, W. Working hours and self-rated health over 7 years: Gender differences in a Korean longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dembe, A.; Erickson, J.; Delbos, R.; Banks, S. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: New evidence from the United States. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès, I.; Borrell, C.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Cascant, L. Gender perspective in the analysis of the relationship between long work hours, health and health-related behavior. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2007, 33, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, K.; Chan, A.; Ngan, S. The Effect of Long Working Hours and Overtime on Occupational Health: A Meta-Analysis of Evidence from 1998 to 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, W. The Influence of Inter-hukou Network on the Mental Health of Rural-to-urban Migrants. Soc. Constr. 2021, 8, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, K.A.; Forman, P.J. Living in a Culture of Overwork: An Ethnographic Study of Flexibility. J. Manag. Inq. 2014, 23, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetti, G.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Guglielmi, D. Are workaholics born or made? Relations of workaholism with person characteristics and overwork climate. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2014, 21, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawanishi, Y. On Karo-Jisatsu (Suicide by Overwork): Why Do Japanese Workers Work Themselves to Death? Int. J. Ment. Health 2008, 37, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, K.; Rindfuss, R. Fertility and Women’s Employment in Industrialized Nations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, S.; Kuziemko, I. Why Do Mothers Breastfeed Girls Less than Boys? Evidence and Implications for Child Health in India. Q. J. Econ. 2011, 126, 1485–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Wu, X. The Consequences of Having a Son on Family Wealth in Urban China. Rev. Income Wealth 2017, 63, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Sánchez-Barricarte, J. Fertility Intention, Son Preference, and Second Childbirth: Survey Findings from Shaanxi Province of China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 125, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, Q.; Ge, T.; Tai, X. Change in China’s Sex Ratio at Birth Since 2000: A Decomposition at the Provincial Level. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2020, 13, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, X. The Competitive Saving Motive: Evidence from Rising Sex Ratios and Savings Rates in China. J. Political Econ. 2011, 119, 511–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y. The number and gender of children and housing choices of Chinese urban families. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 50, 100–107+175. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N. House Prices and Women’s Labor Participation: Evidence from CHNS data. Econ. Perspect. 2016, 11, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki, M. Imbalanced sex ratios and housing prices in the U.S. Growth Chang. 2010, 50, 1441–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossi, G.; Figlio, D.; Giuliano, P.; Sapienza, P. Born in the family: Preferences for boys and the gender gap in math. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021, 183, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, S.; Carvalho, L.; Lleras-Muney, A. Child Gender and Parental Investments in India: Are Boys and Girls Treated Differently? Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2014, 6, 157–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, E.; Hwang, J. Child Gender and Parental Inputs: No More Son Preference in Korea? Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Staiger, D.; Stock, J. Instrumental Variables Regression with Weak Instruments. Econometrica 1997, 65, 557–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J. Guns, Germs and Steel: The Destiny of Human Society; Shanghai Translation Press: Shanghai, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Explanation | Average | SD | Min. | Max. | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overwork | Worked for more than 55 h a week (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 38,375 |

| Working hours | How many hours have you worked this week? | 54.41 | 18.58 | 0 | 99 | 38,375 |

| Age of firstborn | 12.24 | 8.61 | 0 | 18 | 42,158 | |

| Gender of firstborn | 0 = female; 1 = male | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | 42,158 |

| Gender of second child | 0 = female; 1 = male | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 14,460 |

| Primary caregiver of first child | 1 = mother; 0 = others | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 | 41,492 |

| Primary caregiver of second child | 1 = mother; 0 = others | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | 14,460 |

| Labor contract | Type of labor contract (1 = fixed term labor contract; 2 = nonfixed term labor contract; 3 = working without a contract) | 1.77 | 0.68 | 1 | 3 | 14,265 |

| Medical insurance | Involved in the medical insurance system for urban employees (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 | 38,375 |

| Age | Rural–urban migrant women’s age | 35.39 | 8.61 | 20 | 59 | 42,158 |

| Women’s education | 1 = primary school and below; 2 = middle school; 3 = high school; 4 = undergraduate and above | 2.15 | 0.84 | 1 | 4 | 42,158 |

| Spouse’s education | 1 = primary school and below; 2 = middle school; 3 = high school; 4 = undergraduate and above | 2.28 | 0.82 | 1 | 4 | 41,255 |

| Monthly income | Self-income of last month (yuan) | 3395.24 | 2769.18 | −5000 | 90,000 | 34,422 |

| Family income | Family income of last month in the local area (yuan) | 6795.88 | 5178.54 | 0 | 200,000 | 42,158 |

| Family expenditure | Family expenditure of last month in the local area (yuan) | 3493.83 | 2368.03 | 200 | 50,000 | 42,158 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal Effect | Marginal Effect | Marginal Effect | Marginal Effect | |

| Firstborn boy (basic group: firstborn girl) | 0.072 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.051 ** | |

| (4.99) | (4.22) | 1.95 | ||

| Firstborn girl then boy (basic group: firstborn girl then a girl) | 0.079 * | |||

| (1.62) | ||||

| Firstborn boy, then girl | 0.073 * | |||

| (1.43) | ||||

| Firstborn boy, then boy | 0.112 ** | |||

| (2.57) | ||||

| Age of female | 0.090 *** | 0.071 *** | 0.067 ** | −0.079 * |

| (6.65) | (5.23) | (2.54) | (−1.82) | |

| Square of female age | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | 0.001 |

| (−5.49) | (−4.21) | (−2.34) | (1.60) | |

| Education level of female | ||||

| Junior middle school (basic group: elementary and below) | −0.018 | −0.065 * | −0.185 *** | −0.114 * |

| (−0.50) | (−1.79) | (−2.76) | (−1.72) | |

| High school | −0.087 ** | −0.162 *** | −0.389 *** | −0.230 ** |

| (−2.13) | (−3.89) | (−5.13) | (−2.47) | |

| Undergraduate and above | −0.300 *** | −0.401 *** | −0.688 *** | −0.542 *** |

| (−5.93) | (−7.80) | (−7.28) | (−3.26) | |

| Education level of spouse | ||||

| Junior middle school (basic group: elementary and below) | 0.044 | 0.016 | −0.110 | −0.080 |

| (1.28) | (1.38) | (−1.41) | (−1.04) | |

| High school | −0.062 | −0.118 *** | −0.230 *** | −0.302 *** |

| (−1.52) | (−2.42) | (−2.71) | (−3.05) | |

| Undergraduate and above | −0.386 *** | −0.489 *** | −0.324 *** | −0.258 |

| (−7.12) | (−9.12) | (−3.24) | (−1.61) | |

| Monthly disposable income of family | 0.212 *** | 0.050 ** | 0.098 *** | |

| (18.89) | (2.02) | (2.86) | ||

| Monthly family consumption | 0.118 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.095 * | |

| (5.67) | (3.99) | (1.78) | ||

| Labor contract (basic group: working without a labor contract) | −0.137 *** | |||

| (−4.05) | ||||

| Medical insurance (basic group: involved no employees’ medical insurance) | −0.336 *** | |||

| (−5.64) | ||||

| Primary caregiver of the first child (basic group: mother care) | 0.170 *** | 0.036 | ||

| (4.97) | (0.50) | |||

| Primary caregiver of the second child (basic group: mother care) | 0.134 * | |||

| (1.83) | ||||

| Intraprovincial migration (basic group: Intra city migration) | −0.059 | −0.117 | ||

| (−1.25) | (−1.50) | |||

| Interprovincial migration | −0.095 ** | −0.025 | ||

| (−2.04) | (−0.35) | |||

| Intercept | −2.934 *** | −3.998 *** | 2.343 *** | 1.863 ** |

| (−7.68) | (−15.54) | (4.27) | (2.18) | |

| Sample size | 22,013 | 21,415 | 18,520 | 11,467 |

| Variables | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probit | Logit | OLS | |

| One boy (basic group: no-boy) | 0.068 ** | 0.110 ** | 0.026 ** |

| (2.04) | (2.04) | (2.03) | |

| Two boys (basic group: no-boy) | 0.085 ** | 0.137 ** | 0.032 ** |

| (2.16) | (2.15) | (2.15) | |

| Other control variables | YES | YES | YES |

| Intercept | −3.670 *** | −5.944 *** | −0.867 *** |

| (−8.44) | (−8.38) | (−5.33) | |

| Sample size | 11,467 | 11,467 | 11,467 |

| Variables | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Health | Hypertension | Diabetes | |

| Overwork | 0.076 *** | 0.066 ** | 0.076 * |

| (6.15) | (2.36) | (1.66) | |

| Age of female | −0.022 *** | 0.035 ** | −0.048 ** |

| (−3.62) | (2.36) | (−2.34) | |

| Square of female age | 0.000 ** | 0.000 * | 0.001 *** |

| (2.27) | (1.66) | (3.95) | |

| Education level of female | |||

| Junior middle school (basic group: elementary and below) | −0.059 * | −0.169 *** | −0.119 |

| (−1.83) | (−3.54) | (−1.48) | |

| High school and above | −0.038 | −0.366 *** | −0.255 *** |

| (−1.11) | (−6.28) | (−2.68) | |

| The duration of the migration | 0.008 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.014 *** |

| (6.90) | (5.21) | (4.61) | |

| lnwage | −0.025 *** | −0.046 *** | −0.045 *** |

| (−4.57) | (−4.67) | (−3.08) | |

| Medical insurance (basic group: involved no employees’ medical insurance) | −0.066 *** | 0.018 | −0.068 |

| (−5.04) | (0.62) | (−1.44) | |

| Intercept | 0.738 *** | −3.355 *** | −1.779 *** |

| (6.19) | (−10.48) | (−4.20) | |

| Sample size | 40,898 | 39,980 | 39,980 |

| Variables | Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Probit | Logit | |

| Firstborn boy (basic group: firstborn girl) | −0.029 *** | −0.178 *** | −0.338 *** |

| (−4.01) | (−4.21) | (−4.25) | |

| Primary caregiver of first child (basic group: mother care) | −0.011 *** | −0.076 *** | −0.162 *** |

| (−8.79) | (−9.62) | (−10.26) | |

| Other control variables | yes | yes | yes |

| Intercept | 0.334 *** | −2.064 *** | −3.820 *** |

| (3.16) | (−3.02) | (−2.91) | |

| Sample size | 7124 | 7124 | 7124 |

| Variables | Model 16 | Model 17 |

|---|---|---|

| Having Sons | Having Daughters | |

| Marginal effect | Marginal effect | |

| Families without house (basic group: families with house) | 0.137 | 0.106 ** |

| (1.55) | (2.12) | |

| Labor contract (basic group: working without a labor contract) | −0.083 | −0.223 *** |

| (−1.28) | (−6.13) | |

| Medical insurance (basic group: involved no employees’ medical insurance) | −0.593 *** | −0.624 *** |

| (−5.39) | (−9.84) | |

| Other control variables | yes | yes |

| intercept | 5.685 *** | 2.950 *** |

| (3.89) | (3.33) | |

| Sample size | 12,050 | 14,499 |

| Variables | Model 6 | Model 18 IVProbit |

|---|---|---|

| Probit | 2SLS | |

| First stage regression | ||

| Provincial son preference in 2010 | 0.013 ** | |

| (2.03) | ||

| Second stage regression | ||

| Firstborn boy (basic group: firstborn girl) | 0.051 ** | 4.000 * |

| 1.95 | (1.73) | |

| Other control variables | YES | YES |

| Intercept | 2.343 *** | −6.069 *** |

| (4.27) | (−5.91) | |

| Wald’s test (p-value) | - | 9.75 (0.002) |

| Sample size | 18,520 | 26,550 |

| Model 19 | Model 20 | Model 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20–35 Years Old | 35–44 Years Old | 45–59 Years Old | |

| Firstborn boy (basic group: firstborn girl) | 0.054 | 0.136 *** | 0.411 *** |

| (1.98) | (3.58) | (2.79) | |

| Other control variables | YES | YES | YES |

| Intercept | −4.591 *** | −2.210 *** | −3.318 ** |

| (−12.88) | (−10.95) | (−2.95) | |

| Sample size | 20,046 | 9339 | 603 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Wang, R. Child Gender and Married Women’s Overwork: Evidence from Rural–Urban Migrants in China. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061126

Song Y, Wang R. Child Gender and Married Women’s Overwork: Evidence from Rural–Urban Migrants in China. Healthcare. 2022; 10(6):1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061126

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yanjiao, and Ruojing Wang. 2022. "Child Gender and Married Women’s Overwork: Evidence from Rural–Urban Migrants in China" Healthcare 10, no. 6: 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061126

APA StyleSong, Y., & Wang, R. (2022). Child Gender and Married Women’s Overwork: Evidence from Rural–Urban Migrants in China. Healthcare, 10(6), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061126