Co-Produce, Co-Design, Co-Create, or Co-Construct—Who Does It and How Is It Done in Chronic Disease Prevention? A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

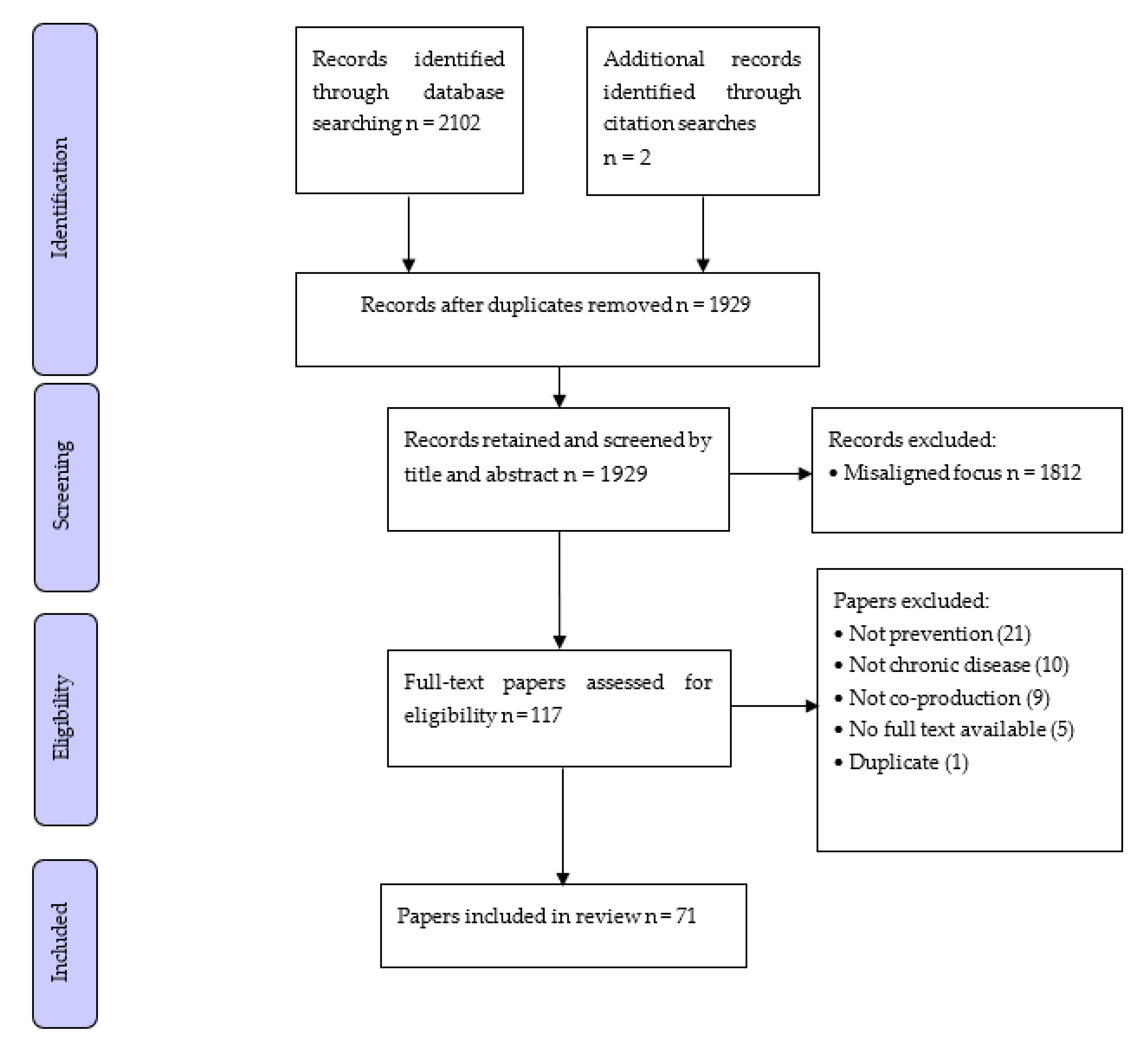

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Publication Country

3.2.2. Prevention Focus

3.2.3. ‘Co-Word’

3.3. The Operationalisation of Co-Production in the Development and Evaluation of Chronic Disease Prevention Interventions

3.4. Those Involved in the Co-Production of Chronic Disease Prevention Interventions

3.5. Evaluation of Chronic Disease Prevention Interventions Developed Using Co-Production

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Practice and Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Impact of Overweight and Obesity as a Risk Factor for Chronic Conditions: Australian Burden of Disease Study; AIHW: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2017.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Australia 2015; AIHW: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Preventive Health. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/preventive-health (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Wutzke, S.; Rowbotham, S.; Haynes, A.; Hawe, P.; Kelly, P.; Redman, S.; Davidson, S.; Stephenson, J.; Overs, M.; Wilson, A. Knowledge mobilisation for chronic disease prevention: The case of the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Nelson, E.; Hager, A.; Price, A. Coproduction: When users define quality. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2020, 29, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, A.; Rowbotham, S.; Grunseit, A.; Bohn-Goldbaum, E.; Slaytor, E.; Wilson, A.; Lee, K.; Davidson, S.; Wutzke, S. Knowledge mobilisation in practice: An evaluation of the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turakhia, P.; Combs, B. Using Principles of Co-Production to Improve Patient Care and Enhance Value. AMA J. Ethic 2017, 19, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, F.; Marsilio, M.; Guglielmetti, C. Co-production in health policy and management: A comprehensive bibliometric review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, D.; Jones, F.; Harris, R.; Robert, G. What outcomes are associated with developing and implementing co-produced interventions in acute healthcare settings? A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuRose, C.; Needham, C.; Mangan, C.; Rees, J. Generating ’good enough’ evidence for co-production. Évid. Policy A J. Res. Debate Pract. 2017, 13, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, K.; Farr, M.; Kothari, A.; Wye, L.; Le May, A. Embracing complexity and uncertainty to create impact: Exploring the processes and transformative potential of co-produced research through development of a social impact model. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Madden, K.; Fletcher, A.; Midgley, L.; Grant, A.; Cox, G.; Moore, L.; Campbell, R.; Murphy, S.; Bonell, C.; et al. Development of a framework for the co-production and prototyping of public health interventions. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.P.; Radnor, Z.; Strokosch, K. Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A suitable case for treatment? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Nabatchi, T. Getting Back to Basics: Advancing the Study and Practice of Coproduction. Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabatchi, T.; Sancino, A.; Sicilia, M. Varieties of Participation in Public Services: The Who, When, and What of Coproduction. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.W.; O’Neill, M.; Westphal, M.; Morisky, D.; Editors, G. The Challenges of Participatory Action Research for Health Promotion; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Redman, S.; Greenhalgh, T.; Adedokun, L.; Staniszewska, S.; Denegri, S. Co-production of knowledge: The future. BMJ 2021, 372, n434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.M.; Finegood, D.T. Cross-Sector Partnerships and Public Health: Challenges and Opportunities for Addressing Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases Through Engagement with the Private Sector. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly-Smith, A.; Quarmby, T.; Archbold, V.S.J.; Corrigan, N.; Wilson, D.; Resaland, G.K.; Bartholomew, J.B.; Singh, A.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Sherar, L.B.; et al. Using a multi-stakeholder experience-based design process to co-develop the Creating Active Schools Framework. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffe, L.; Hillier-Brown, F.; Hildred, N.; Worsnop, M.; Adams, J.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Penn, L.; Wrieden, W.; Summerbell, C.; A Lake, A.; et al. Feasibility of working with a wholesale supplier to co-design and test acceptability of an intervention to promote smaller portions: An uncontrolled before-and-after study in British Fish & Chip shops. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, S.O.; Bailey, D.P.; Brierley, M.L.; Hewson, D.J.; Chater, A.M. Breaking barriers: Using the behavior change wheel to develop a tailored intervention to overcome workplace inhibitors to breaking up sitting time. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, B.J.R.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Murphy, R.C.; Graves, L.; Whyte, G.; Gillison, F.B.; Crone, D.; Wilson, P.M.; Watson, P.M. Making a move in exercise referral: Co-development of a physical activity referral scheme. J. Public Health 2018, 40, e586–e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, B.J.; Thijssen, D.H.; Murphy, R.C.; Graves, L.; Whyte, G.; Gillison, F.; Crone, D.; Wilson, P.M.; Hindley, D.; Watson, P.M. Preliminary effects and acceptability of a co-produced physical activity referral intervention. Health Educ. J. 2019, 78, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guell, C.; Panter, J.; Griffin, S.; Ogilvie, D. Towards co-designing active ageing strategies: A qualitative study to develop a meaningful physical activity typology for later life. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.; Goyder, E.; Eves, F. Acceptability and feasibility of a low-cost, theory-based and co-produced intervention to reduce workplace sitting time in desk-based university employees. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, P.; van Marwijk, H.; Gibson, L.; Musinguzi, G.; Anthierens, S.; Ford, E.; Bremner, S.A.; Bowyer, M.; Le Reste, J.Y.; Sodi, T.; et al. A protocol paper: Community engagement interventions for cardiovascular disease prevention in socially disadvantaged populations in the UK: An implementation research study. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, L.; Amaugo, L.; Ochieng, B.M.N. Developing healthy weight maintenance through co-creation: A partnership with Black African migrant community in East Midlands. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.; Hughes, A.; Gibson, A.-M.; Haines, J.; Taveras, E.; Reilly, J.J. Protocol for Healthy Habits Happy Homes (4H) Scotland: Feasibility of a participatory approach to adaptation and implementation of a study aimed at early prevention of obesity. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.; Magee, E.; White, A.; Stewart, L. Eat, play, learn well—a novel approach to co-production and analysis grid for environments linked to obesity to engage local communities in a child healthy weight action plan. Public Health 2019, 166, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; A Skelton, D.; Chastin, S.F. Co-creating a tailored public health intervention to reduce older adults’ sedentary behaviour. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K.; Van Godwin, J.; Darwent, K.; Fildes, A. Formative research to develop a school-based, community-linked physical activity role model programme for girls: CHoosing Active Role Models to INspire Girls (CHARMING). BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Valk, C.; Steenbakkers, J.; Bekker, T.; Visser, T.; Proctor, G.; Toshniwal, O.; Langberg, H. Can technology adoption for older adults be co-created? Gerontechnology 2017, 16, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidding, L.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Belmon, L.S.; Altenburg, T.M. Co-creating a 24-hour movement behavior tool together with 9–12-year-old children using mixed-methods: MyDailyMoves. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lems, E.; Hilverda, F.; Broerse, J.E.W.; Dedding, C. ‘Just stuff yourself’: Identifying health-promotion strategies from the perspectives of adolescent boys from disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lems, E.; Hilverda, F.; Sarti, A.; Van Der Voort, L.; Kegel, A.; Pittens, C.; Broerse, J.; Dedding, C. ‘McDonald’s Is Good for My Social Life’. Developing Health Promotion Together with Adolescent Girls from Disadvantaged Neighbourhoods in Amsterdam. Child. Soc. 2020, 34, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselma, M.; Altenburg, T.M.; Emke, H.; Van Nassau, F.; Jurg, M.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Jurkowski, J.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Co-designing obesity prevention interventions together with children: Intervention mapping meets youth-led participatory action research. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselma, M.; Chinapaw, M.; Altenburg, T. “Not Only Adults Can Make Good Decisions, We as Children Can Do That as Well” Evaluating the Process of the Youth-Led Participatory Action Research ‘Kids in Action’. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, B.; Manon, P.; Johanne, F.; Nathalie, B.; Lorthios-Guilledroit, A.; Marie-Ève, M. Development and implementation of a community-based pole walking program for older adults. Act. Adapt. Aging 2019, 43, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heerik, R.A.M.; van Hooijdonk, C.M.J.; Burgers, C.; Steen, G.J. “Smoking Is Sooo. Sandals and White Socks”: Co-Creation of a Dutch Anti-Smoking Campaign to Change Social Norms. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Folkvord, F. Systematically testing the effects of promotion techniques on children’s fruit and vegetables intake on the long term: A protocol study of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verloigne, M.; Altenburg, T.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Chastin, S.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Using a Co-Creational Approach to Develop, Implement and Evaluate an Intervention to Promote Physical Activity in Adolescent Girls from Vocational and Technical Schools: A Case Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latomme, J.; Morgan, P.; De Craemer, M.; Brondeel, R.; Verloigne, M.; Cardon, G. A Family-Based Lifestyle Intervention Focusing on Fathers and Their Children Using Co-Creation: Study Protocol of the Run Daddy Run Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeeg, D.; Christensen, U.; Grabowski, D. Co-Designing an Intervention to Prevent Overweight and Obesity among Young Children and Their Families in a Disadvantaged Municipality: Methodological Barriers and Potentials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallentin-Holbech, L.; Guldager, J.D.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Majgaard, G.; Lyk, P.; Stock, C. Co-Creating a Virtual Alcohol Prevention Simulation with Young People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, M.; Murtagh, E. ‘No one ever asked us’: A feasibility study assessing the co-creation of a physical activity programme with adolescent girls. Glob. Health Promot. 2020, 27, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosis, S.; Pennucci, F.; Noto, G.; Nuti, S. Healthy Living and Co-Production: Evaluation of Processes and Outcomes of a Health Promotion Initiative Co-Produced with Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addario, M.; Baretta, D.; Zanatta, F.; Greco, A.; Steca, P. Engagement Features in Physical Activity Smartphone Apps: Focus Group Study with Sedentary People. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e20460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooses, K.; Vihalemm, T.; Uibu, M.; Mägi, K.; Korp, L.; Kalma, M.; Mäestu, E.; Kull, M. Developing a comprehensive school-based physical activity program with flexible design—from pilot to national program. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janols, R.; Lindgren, H. A Method for Co-Designing Theory-Based Behaviour Change Systems for Health Promotion. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 235, 368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Skerletopoulos, L.; Makris, A.; Khaliq, M. “Trikala Quits Smoking”: A Citizen Co-Creation Program Design to Enforce the Ban on Smoking in Enclosed Public Spaces in Greece. Soc. Mark. Q. 2020, 26, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perignon, M.; Dubois, C.; Gazan, R.; Maillot, M.; Muller, L.; Ruffieux, B.; Gaigi, H.; Darmon, N. Co-construction and Evaluation of a Prevention Program for Improving the Nutritional Quality of Food Purchases at No Additional Cost in a Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Population. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, e001107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Martin, A.; Caon, M.; Adorni, F.; Andreoni, G.; Ascolese, A.; Atkinson, S.; Bul, K.; Carrion, C.; Castell, C.; Ciociola, V.; et al. A Mobile Phone Intervention to Improve Obesity-Related Health Behaviors of Adolescents Across Europe: Iterative Co-Design and Feasibility Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e14118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standoli, C.E.; Guarneri, M.R.; Perego, P.; Mazzola, M.; Mazzola, A.; Andreoni, G. Smart Wearable Sensor System for Counter-Fighting Overweight in Teenagers. Sensors 2016, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, G.S.; Bovill, M.; Pollock, L.; Bonevski, B.; Gruppetta, M.; Atkins, L.; Carson-Chahhoud, K.; Boydell, K.M.; Gribbin, G.R.; Oldmeadow, C.; et al. Feasibility and acceptability of Indigenous Counselling and Nicotine (ICAN) QUIT in Pregnancy multicomponent implementation intervention and study design for Australian Indigenous pregnant women: A pilot cluster randomised step-wedge trial. Addict. Behav. 2019, 90, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, S.R.; Raeside, R.; Latham, Z.; Singleton, A.C.; Hyun, K.; Grunseit, A.; Steineck, K.; Redfern, J. ’Not to Be Harsh but Try Less to Relate to ’the Teens’ and You’ll Relate to Them More’: Co-Designing Obesity Prevention Text Messages with Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, J.; Cox, H.; Lopes, E.; Motlik, J.; Hanson, L. Supporting youth wellbeing with a focus on eating well and being active: Views from an Aboriginal community deliberative forum. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2018, 42, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durl, J.; Trischler, J.; Dietrich, T. Co-designing with young consumers—Reflections, challenges and benefits. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, J.Y.; Engelen, L.; Burks-Young, S.; Daley, M.; Maxwell, J.-K.; Milton, K.; Bauman, A. Perspectives on a ‘Sit Less, Move More’ Intervention in Australian Emergency Call Centres. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, E.; McGrath, R. Promoting physical activity among children and youth in disadvantaged South Australian CALD communities through alternative community sport opportunities. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2016, 27, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D.; Do, H.; To, Q.G.; Vo, B.; Goris, J.; Alraman, H. The effectiveness of living well multicultural-lifestyle management program among ethnic populations in Queensland, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021, 32, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehring, E.; Ferguson, M.; Brown, C.; Murtha, K.; Laws, C.; Cuthbert, K.; Thompson, K.; Williams, T.; Hammond, M.; Brimblecombe, J. Supporting healthy drink choices in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: A community-led supportive environment approach. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2019, 43, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, C.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; Klassen, K.M.; Palermo, C.; Walker, T.; Lim, M.S.; Dean, M.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Truby, H. Communicating health-Optimising young adults’ engagement with health messages using social media: Study protocol. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 75, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogomolova, S.; Carins, J.; Dietrich, T.; Bogomolov, T.; Dollman, J. Encouraging healthier choices in supermarkets: A co-design approach. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2439–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovill, M.; Chamberlain, C.; Bennett, J.; Longbottom, H.; Bacon, S.; Field, B.; Hussein, P.; Berwick, R.; Gould, G.; O’mara, P. Building an Indigenous-Led Evidence Base for Smoking Cessation Care among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women during Pregnancy and Beyond: Research Protocol for the Which Way? Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, J.; McMahon, E.; Ferguson, M.; De Silva, K.; Peeters, A.; Miles, E.; Wycherley, T.; Minaker, L.; Greenacre, L.; Gunther, A.; et al. Effect of restricted retail merchandising of discretionary food and beverages on population diet: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e463–e473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carins, J.; Bogomolova, S. Co-designing a community-wide approach to encouraging healthier food choices. Appetite 2021, 162, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, S.; Sano, Y.; Braun, B.; Maring, E.F. Shaping Core Health Messages: Rural, Low-Income Mothers Speak through Participatory Action Research. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nu, J.; Bersamin, A. Collaborating with Alaska Native Communities to Design a Cultural Food Intervention to Address Nutrition Transition. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2017, 11, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, M.; Seth, J.G.; Atwood, R.D.; Ray, T.C. Development and Implementation of Client-Centered Nutrition Education Programs in a 4-Stage Framework. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e65–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Dupuis, V.; Tyron, M.; Crane, M.R.; Garvin, T.; Pierre, M.; Shanks, C.B. Intended and Unintended Consequences of a Community-Based Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Dietary Intervention on the Flathead Reservation of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckerman-Hsu, J.P.; Aftosmes-Tobio, A.; Gavarkovs, A.; Kitos, N.; Figueroa, R.; Kalyoncu, Z.B.; Lansburg, K.; Yu, X.; Kazik, C.; Vigilante, A.; et al. Communities for Healthy Living (CHL) A Community-based Intervention to Prevent Obesity in Low-Income Preschool Children: Process Evaluation Protocol. Trials 2020, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistura, M.; Fetterly, N.; Rhodes, R.E.; Tomlin, D.; Naylor, P.-J. Examining the Efficacy of a ’Feasible’ Nudge Intervention to Increase the Purchase of Vegetables by First Year University Students (17–19 Years of Age) in British Columbia: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, H.; Nettlefold, L.; Bauman, A.; Hoy, C.; Gray, S.M.; Lau, E.; Sims-Gould, J. Implementation of a co-designed physical activity program for older adults: Positive impact when delivered at scale. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Morenga, L.; Pekepo, C.; Corrigan, C.; Matoe, L.; Mules, R.; Goodwin, D.; Dymus, J.; Tunks, M.; Grey, J.; Humphrey, G.; et al. Co-designing an m, Health tool in the New Zealand Māori community with a “Kaupapa Māori” approach. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2018, 14, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbiest, M.; Borrell, S.; Dalhousie, S.; Tupa’I-Firestone, R.; Funaki, T.; Goodwin, D.; Grey, J.; Henry, A.; Hughes, E.; Humphrey, G.; et al. A Co-Designed, Culturally-Tailored mHealth Tool to Support Healthy Lifestyles in Māori and Pasifika Communities in New Zealand: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e10789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, P.C.; Romano, L.B.; Frohlich, D.; Lorenzi, L.J.; Campos, L.B.; Paixão, A.; Bet, P.; Deutekom, M.; Krose, B.; Dourado, V.Z.; et al. Tailoring digital apps to support active ageing in a low income community. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santina, T.; Beaulieu, D.; Gagné, C.; Guillaumie, L. Using the intervention mapping protocol to promote school-based physical activity among children: A demonstration of the step-by-step process. Health Educ. J. 2020, 79, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Redfern, J. Strategies to Engage Adolescents in Digital Health Interventions for Obesity Prevention and Management. Healthcare 2018, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeside, R.; Partridge, S.R.; Singleton, A.; Redfern, J. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Adolescents: eHealth, Co-Creation, and Advocacy. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.; Raeside, R.; Singleton, A.; Redfern, J.; Partridge, S.R. Limited Engaging and Interactive Online Health Information for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Australian Websites. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, H.; Jull, A.; Dobson, R.; Firestone, R.; Whittaker, R.; Morenga, L.T.; Goodwin, D.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Co-design of mHealth Delivered Interventions: A Systematic Review to Assess Key Methods and Processes. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, L.; Truesdale, M.; Dunkley, A.; House, A.; Russell, A.M. Health Promotion and Wellness Initiatives Targeting Chronic Disease Prevention and Management for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Recent Advancements in Type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2018, 5, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taggart, L.; Doherty, A.J.; Chauhan, U.; Hassiotis, A. An exploration of lifestyle/obesity programmes for adults with intellectual disabilities through a realist lens: Impact of a ‘context, mechanism and outcome’ evaluation. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 34, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rütten, A.; Frahsa, A.; Abel, T.; Bergmann, M.; de Leeuw, E.; Hunter, D.; Jansen, M.; King, A.; Potvin, L. Co-producing active lifestyles as whole-system-approach: Theory, intervention and knowledge-to-action implications. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, K.E.; Gardner, L.A.; Mc Gowan, C.; Chapman, C.; Thornton, L.; Parmenter, B.; McBride, N.; Lubans, D.R.; McCann, K.; Spring, B.; et al. A Web-Based Intervention to Prevent Multiple Chronic Disease Risk Factors Among Adolescents: Co-Design and User Testing of the Health4Life School-Based Program. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e19485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris-John, R.; Dizon, L.; Sutcliffe, K.; Kang, K.; Fleming, T. Co-creating a large-scale adolescent health survey integrated with access to digital health interventions. Digit. Health 2020, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, J.; Canfell, O.J.; Walker, J.L.; Webb, K.-L.; Brignano, S.; Peu, T.; Santos, D.; Kira, K.; Littlewood, R. Healthier Together: Co-design of a culturally tailored childhood obesity community prevention program for Maori & Pacific Islander children and families. Health Promot. J. Aust. Off. J. Aust. Assoc. Health Promot. Prof. 2021, 32 (Suppl. 1), 143–154.

- Parder, M.-L. Possibilities for Co-Creation in Adolescents’ Alcohol Prevention. J. Creative Commun. 2020, 15, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennessy, G.; Burstein, F. Role of Information Professionals as Intermediaries for Knowledge Management in Evidence-Based Healthcare. Healthcare Knowledge Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C.; Thorpe, L.; Trefusis, H.; Kousoulis, A. Unlocking the potential for digital mental health technologies in the UK: A Delphi exercise. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, D.; Namioka, A. Participatory Design: Principles and Practices; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Blomkamp, E. The promise of co-design for public policy. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, B.; Evers, A. An Ambiguous Concept: On the Meanings of Co-production for Health Care Users and User Organizations? VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2012, 25, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R.; Manna, R. What if things go wrong in co-producing health services? Exploring the implementation problems of health care co-production. Policy Soc. 2017, 37, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. REVIEW OF COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; MacDougall, C.; Smith, D. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, P.; Saeri, A.K.; Bragge, P. Research co-design in health: A rapid overview of reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, K.; Kothari, A.; Mays, N. The dark side of coproduction: Do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Res. Policy Syst. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year | Purpose of Study | Type of Co-Production | Prevention Focus | Target Population | Collaboration Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carins 2021 | Formative | Co-design, -create | Healthy eating | Supermarket consumers | Workshops |

| Hardt 2021 | Formative | Co-design | Obesity prevention | Children | Survey, discussion groups, interviews |

| Mooses 2021 | Formative | Co-create, -design | Physical activity | Children/adolescents (7–16 years) | Network building, school visits |

| Ochieng 2021 | Formative | Co-create | Healthy weight | Children (ethnic minority) | Focus groups, workshops |

| Castro 2020 | Formative | Co-design, -create | Physical activity | Low-income adults (40–90 years) | Focus groups |

| Champion 2020 | Formative | Co-design | Lifestyle risk factors | Secondary school students | Survey, focus groups |

| Corr 2020 | Formative, impact | Co-create | Physical activity | Adolescent girls (15–17 years) | Questionnaire, focus groups |

| D’Addario 2020 | Formative | Co-design | Physical activity | Physically inactive adults | Focus groups |

| Daly-Smith 2020 | Formative | Co-produce, -design, -develop | Physical activity | School-aged children/adolescents | Stakeholder workshops |

| Hidding 2020 | Formative | Co-create | Physical activity | Children (9–12 years old) | Concept mapping, focus groups |

| Martin 2020 | Formative | Co-design | Healthy weight | Adolescents (13–16 years) | Workshop, individual testing |

| Parder 2020 | Formative | Co-create, -produce | Alcohol abuse prevention | Adolescents (13–15 years) | Workshops, storytelling |

| Peiris-Hohn 2020 | Formative, process | Co-design, co-create | ‘Health’ including PA | Adolescents (16+ years) | Group sessions, workshops |

| Lems 2020 Lems 2019 | Formative Formative | Co-create | Health promotion | Adolescent girls (12–15 years) and boys (12–18 years) | Small group sessions |

| Anselma 2019 Anselma 2020 | Formative Process | Co-design, -create Co-create, -develop | Healthy lifestyle | Children (9–12 years) | Group sessions |

| Fournier 2019 | Formative, process | Co-construct | Physical inactivity | Older adults | Group sessions, interviews |

| Gillespie 2019 | Formative | Co-produce | Obesity prevention | Primary school-aged children | Focus groups, interviews |

| Goffe 2019 | Formative | Co-design | Food portion sizing | Food outlet owners/managers | Discussions, engagement event |

| Gould 2019 | Formative | Co-design | Smoking cessation | Pregnant Indigenous women | Not specified |

| Hoeeg 2019 | Formative | Co-design, -create | Obesity prevention | Families of preschool children | Workshops |

| Mammen 2019 | Formative | Co-create | Health messages | Rural, low-income mothers | Focus groups, interviews |

| Mistura 2019 | Formative, impact | Co-design | Food purchasing | First-year university students | Focus groups, surveys |

| Morgan 2019 | Formative | Co-produce | Physical activity | Girls (9–11 years) | Focus groups, interviews |

| Ojo 2019 | Formative | Co-create | Workplace sitting | Desk-based workers | Interviews |

| Partridge 2019 | Formative | Co-design | Obesity prevention | Adolescents (13–18 years) | Workshop, survey |

| Santina 2019 | Formative | Co-design, -develop | Physical activity | Children (10–12 years) | Group meetings |

| Buckley 2018 Buckley 2019 | Formative Process, impact | Co-develop, -produce Co-produce | Physical activity | Adults with controlled lifestyle-related health issues | Group meetings, focus groups, survey |

| Guell 2018 | Formative | Co-design, -develop | Physical activity | Older adults | Interviews, workshops |

| Street 2018 | Formative | Co-construct, -create, -produce | Health policy | Aboriginal people | Deliberative forum, storyboard |

| Te Morenga 2018 | Formative | Co-design | Obesity prevention | Maori people | Focus groups |

| Verbiest 2018 | Protocol | Co-design | Healthy lifestyle behaviour | Adult Maori people | |

| Durl 2017 | Formative | Co-design | Alcohol education | Adolescents (14–16 years) | Workshop, feedback, observations |

| Hawkins 2017 | Formative | Co-produce | Smoking prevention | Adolescents (12–19 years) | Focus groups, interviews, observations |

| Janols 2017 | Formative | Co-design | Health behaviour change | Older adults | Workshops |

| Leask 2017 | Formative | Co-create | Sedentary behaviour | Older adults | Workshops |

| Verloigne 2017 | Formative, impact | Co-create | Physical activity | Adolescent girls (16 years) | Groups |

| Yuan 2017 | Formative | Co-create | Physical activity | Older adults | Workshops |

| Chau 2016 | Formative | Co-design | Sedentary behaviour | Adult call-centre workers | Not specified |

| Nu 2016 | Formative | Co-design | Dietary pattern change | Indigenous community | Working group |

| Rosso 2016 | Formative, impact | Co-design | Health promotion (sport) | Children and youth | Interviews, surveys |

| Standoli 2016 | Formative | Co-design | Obesity prevention | Adolescents | Focus groups |

| Isbell 2015 | Formative | Co-create | Nutrition education | Women, infants, children | Strategic planning meetings |

| Mackenzie 2015 | Formative | Co-produce | Sitting | University employees | Not specified |

| Vallentin-Holbech 2020 | Process | Co-create | Alcohol consumption | Adolescents (15–18 years) | Workshops, interviews, virtual simulation |

| van den Heerik 2017 | Process | Co-create | Smoking prevention | Youth (15–25 years) | Social media, linguistic analysis |

| Ahmed 2020 | Impact, process | Co-design | Healthy eating | Indigenous tribal community | Focus group interviews |

| Bogomolova 2021 | Impact | Co-design, -create | Healthy eating | Supermarket consumers | Workshops |

| Brimblecombe 2020 | Impact | Co-design | Healthy eating | Remote Aboriginal communities | Working groups |

| Gallegos 2020 | Impact | Co-design | Chronic disease | Ethnic communities | Not specified |

| De Rosis 2020 | Impact, process | Co-produce, -design | Obesity prevention | Adolescents | Questionnaire (for evaluation) |

| Skerletopoulos 2020 | Impact, process | Co-create | Smoking indoors | Citizens, commercial stakeholders | |

| Fehring 2019 | Impact | Co-design | Water consumption | Remote Aboriginal communities | Group meetings |

| McKay 2018 | Impact | Co-design | Physical activity | Older adults | Workshops |

| Perignon 2017 | Impact, formative | Co-construct | Healthy eating | Socioeconomic disadvantage | Workshops, interviews |

| Beckerman-Hsu 2020 | Protocol (process) | Co-design | Obesity prevention | Low-income preschool children | Focus groups, interviews |

| Bovill 2021 | Protocol (formative) | Co-design, -develop | Smoking cessation | Pregnant Aboriginal women | Yarning circles, e-mail survey |

| Latomme 2021 | Protocol (formative) | Co-create | Physical activity | Fathers and their children | Group sessions, interviews |

| Nahar 2020 | Protocol (process) | Co-produce, -design | Cardiovascular prevention | Disadvantaged populations | Focus groups, questionnaires, interviews |

| Folkvord 2019 | Protocol (formative) | Co-create | Fruit and vegetable intake | Children (7–13 years) | Focus groups |

| Lombard 2018 | Protocol (formative) | Co-design, -create | Healthy eating | Young adults (18–24 years) | Social media, interviews, workshops |

| Gillespie 2019 | Protocol (process) | Co-produce | Obesity prevention | Preschool-aged children | Group meetings |

| Review style papers | |||||

| Taggart 2021 | Review | Co-produce | Obesity | Adults (intellectual disabilities) | Workshops |

| Ruan 2020 | Review | Co-design | Health behaviours | Adolescents | Content analysis |

| Rutten 2019 | Review, comment | Co-produce | Active lifestyles | Population-wide | Systems approach |

| Partridge 2018 | Review | Co-design | Healthy lifestyle | Adolescents | Focus groups, interviews |

| Raeside 2018 | Review | Co-create | Healthy behaviours | Adolescents | Focus groups, workshops |

| Taggart 2018 | Review | Co-design, -develop, -produce | Type 2 diabetes prevention | Adults (intellectual disabilities) | Focus groups, interviews |

| Eyles 2016 | Review | Co-design | Health behaviour change | Not limited by population | Not limited by collaborative technique |

| Technique | Co-Design | Co-Create | Co-Produce | Co-Construct | Combination | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | N | |

| Group session | 12 (34) | 10 (28.6) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (2.9) | 8 (22.9) | 35 |

| Workshop | 7 (35.0) | 5 (25.0) | 2 (10.0) | 6 (30.0) | 20 | |

| Interviews | 4 (25.0) | 4 (25.0) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (18.8) | 16 |

| Survey/questionnaire | 5 (45.5) | 2 (18.2) | 4 (36.4) | 11 | ||

| Storytelling | 3 (100.0) | 3 | ||||

| Social media | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 | |||

| Observation | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 | |||

| Event | 1 (100.0) | 1 | ||||

| School visit | 1 (100.0) | 1 | ||||

| Virtual simulation | 1 (100.0) | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGill, B.; Corbett, L.; Grunseit, A.C.; Irving, M.; O’Hara, B.J. Co-Produce, Co-Design, Co-Create, or Co-Construct—Who Does It and How Is It Done in Chronic Disease Prevention? A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040647

McGill B, Corbett L, Grunseit AC, Irving M, O’Hara BJ. Co-Produce, Co-Design, Co-Create, or Co-Construct—Who Does It and How Is It Done in Chronic Disease Prevention? A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2022; 10(4):647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040647

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGill, Bronwyn, Lucy Corbett, Anne C. Grunseit, Michelle Irving, and Blythe J. O’Hara. 2022. "Co-Produce, Co-Design, Co-Create, or Co-Construct—Who Does It and How Is It Done in Chronic Disease Prevention? A Scoping Review" Healthcare 10, no. 4: 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040647

APA StyleMcGill, B., Corbett, L., Grunseit, A. C., Irving, M., & O’Hara, B. J. (2022). Co-Produce, Co-Design, Co-Create, or Co-Construct—Who Does It and How Is It Done in Chronic Disease Prevention? A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 10(4), 647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040647