Factors Associated with Coping Behaviors of Abused Women: Findings from the 2016 Domestic Violence Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Data, and Study Samples

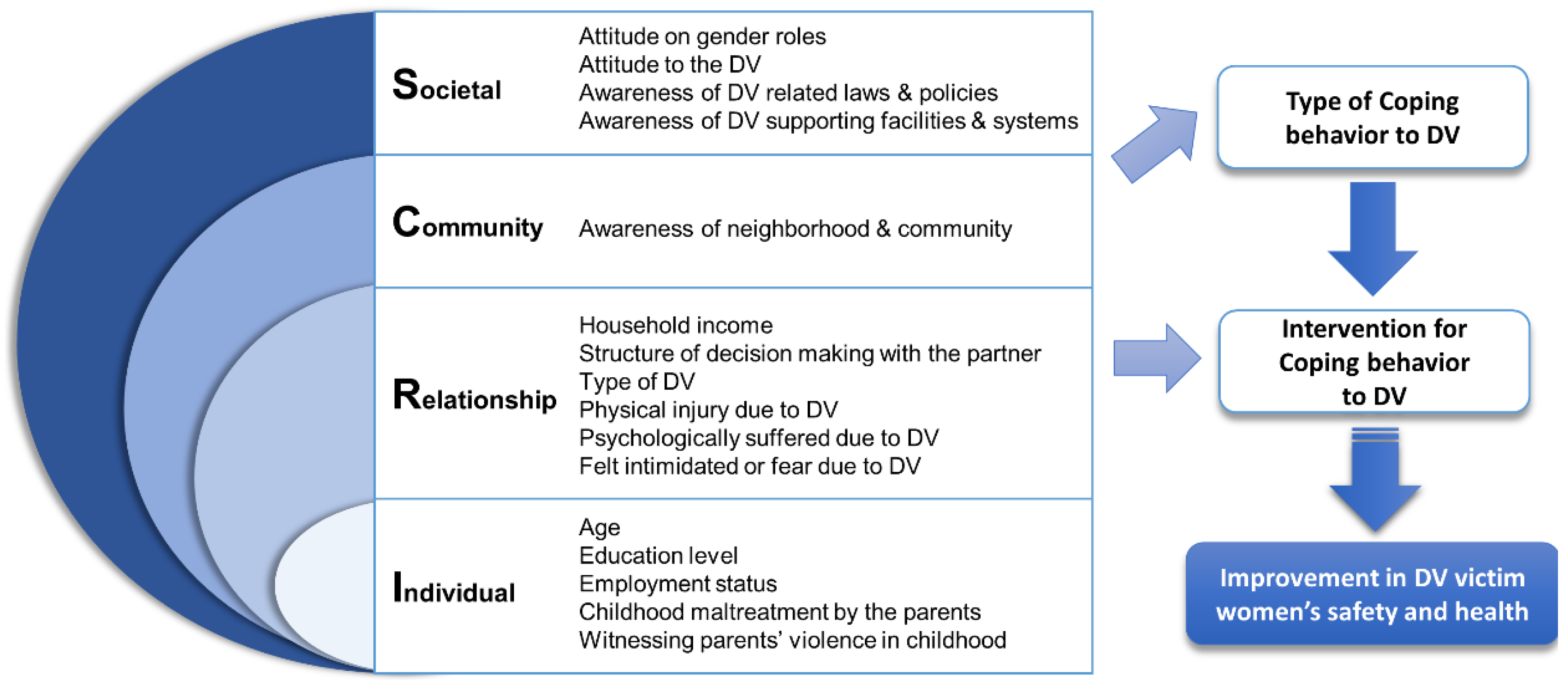

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

2.2.2. Independent Variables

Individual Level

Relationship Level

Community Level

Societal Level

2.2.3. Validity and Reliability

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Prospect

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Women. A Framework to Underpin Action to Prevent Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/11/prevention-framework (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global Fact Sheet. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341604 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Lee, I.S.; Hwang, J.I.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, Y.J. Domestic Violence in Korea: Focusing on Spousal Violence and Child Abuse. Korean Women’s Development Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2017. Available online: https://scienceon.kisti.re.kr/srch/selectPORSrchReport.do?cn=TRKO201800022399 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Choi, M.; Harwood, J. A Hypothesized model of Korean women’s responses to abuse. J. Transcult. Nur. 2004, 15, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family MoGEa. The Domestic Violence Survey in 2007; Contract No.: 2008-02; Ministry of Gender Equality and Family: Seoul, Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Plan of Action to Strengthen the Role of the Health System within a National Multisectoral Response to Address Interpersonal Violence, in Particular against Women and Girls and Against Children. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/global-plan-of-action/en (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Pomeroy, E.C.; Bohman, T.M. Intimate partner violence and psychological health in a sample of Asian and Caucasian women: The roles of social support and coping. J. Fam. Viol. 2007, 22, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatro, M.; Singh, S.P. Coping strategies of women survivors of domestic violence residing with an abusive partner after registered complaint with the family counseling center at Alwar, India. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 818–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, K.M.; Litwack, S.D.; Pineles, S.L.; Suvak, M.K.; Vaughn, R.A.; Resick, P.A. Predictors of intimate partner violence revictimization: The relative impact of distinct PTSD symptoms, dissociation, and coping strategies. J. Trauma. Stress 2013, 26, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, C.M.; Sawhney, D.K. Coping with domestic violence: Control attributions, dysphoria, and hopelessness. J. Trauma. Stress 2000, 13, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.M.; Renner, L.M.; Bloom, T.S. Rural women’s strategic responses to intimate partner violence. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayem, A.M.; Khan, M.A.U. Women’s strategic responses to intimate partner violence: A study in a rural community of Bangladesh. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 2012, 6, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, A.E.; Resick, P.A. Coping among adult female victims of domestic violence. J. Fam. Violence 2004, 19, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.R. The effects of post-traumatic negative cognitions and coping strategies on post-traumatic stress and emotional symptoms in female victims of domestic violence. Cogn. Behav. Ther. Korea 2013, 13, 445–467. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.J. The Effects of Perceived Control and Avoidance Coping on Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Female Victims of Domestic Violence. Master’s Thesis, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, Social Support, and Women; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Act on the Prevention of Domestic Violence and Protection, ETC. of Victims. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?menuId=1&subMenuId=15&tabMenuId=81&query#AJAX (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Korea, S. Statistical Quality Control System. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/aboutUs/5/5/index.static (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Straus, M.A.; Hamby, S.L.; Boney-McCoy, S.U.E.; Sugarman, D.B. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. J. Fam. Issues. 1996, 17, 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family MoGEa. The Domestic Violence Survey in 2016; Contract No.: 2016-2041; Ministry of Gender Equality and Family: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Nam, K.A.; Park, J.H.; Lee, H.H. Characteristics and mental health of battered women in shelters. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2003, 33, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Schepp, K.G. Understanding Korean Families With Alcoholic Fathers in a View of Confucian Culture. J. Addict. Nurs. 2015, 26, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, A.Y.; Wan, M.L.E.; Hayter, M. The lived experience of women victims of intimate partner violence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 2336–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Goodman, L.; Tummala-Narra, P.; Weintraub, S. A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2005, 36, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Park, S. Experiencing coercive control in female victims of dating violence. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2019, 49, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, S.; Bible, A. Battered Women’s Protective Strategies. The National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (NRCDV): Harrisburg, PA, USA, 2009. Available online: https://vawnet.org/material/battered-womens-protective-strategies (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Chang, H.S.; Hwang, S. Changes in coping and experiential knowledge among female victims of intimate partner violence: A focus on women receiving services from a clinical setting. J. Future Soc. Work. Res. 2019, 10, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihama, M. Battered women’s coping strategies and psychological distress: Differences by immigration status. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follingstad, D.R.; Neckerman, A.P.; Vormbrock, J. Reactions to victimization and coping strategies of battered women: The ties that bind. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 8, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Park, Y. Crisis experience of domestic violence in women: Focus group interview. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs. 2017, 31, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ko, Y. Victims of intimate partner violence in South Korea: Experiences in seeking help based on support selection. Violence Against Won. 2021, 27, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.C. Changes in sex roles in Korean society: The present state and responses. Soc. Soc. Theory 2010, 17, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.S. Northeast Asian familism and the social status of Korean women: Labor-market familism vs (limited) individualization of family behavior. Dongbuga Yeoksa Nonchong 2017, 58, 372–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, S.Y.J.; Yoo, I.Y.; Ahn, Y.H. Experience of violence and health status of battered women in shelters. J. Korean Public Health Nurs. 2008, 22, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.A.; Feder, G.S. Help-seeking amongst women survivors of domestic violence: A qualitative study of pathways towards formal and informal support. Health Expect. 2016, 19, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/24159358X/en/ (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Campbell, J.C. Helping women understand their risk in situations of intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ecolog-ical Model | Variable | Categories | Weighted % or Mean (SD) | χ2/F | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Did Nothing n = 198 (64.8%) | Escaped the SOV or Ran Outside n = 77 (25.1%) | Became Reciproc-Ally Violent n = 34 (10.1%) | |||||

| I | Age (years) | 19–39 | 20.4 | 63.3 | 16.3 | 20.4 | 9.64 * | |

| 40–59 | 57.5 | 65.2 | 25.4 | 9.4 | ||||

| 60 or more | 22.1 | 64.1 | 32.1 | 3.8 | ||||

| Education level | At least middle school | 19.7 | 70.2 | 27.7 | 2.1 | 9.13 | ||

| High school | 56.1 | 64.2 | 26.9 | 8.9 | ||||

| College or higher | 24.2 | 62.0 | 19.0 | 19.0 | ||||

| Employment status | Employed | 51.5 | 60.2 | 26.8 | 13.0 | 3.38 | ||

| Unemployed | 48.5 | 69.8 | 23.3 | 6.9 | ||||

| Childhood maltreatment by parents | Yes | 78.7 | 64.4 | 25.0 | 10.6 | 0.35 | ||

| No | 21.3 | 66.7 | 25.5 | 7.8 | ||||

| Witnessing violence among parents in childhood | Yes | 61.7 | 60.1 | 28.4 | 11.5 | 3.37 | ||

| No | 38.3 | 71.7 | 19.6 | 8.7 | ||||

| R | Household income | Less than 4,000,000 won | 52.7 | 64.3 | 28.6 | 7.1 | 3.52 | |

| 4,000,000 won or more | 47.3 | 65.5 | 21.2 | 13.3 | ||||

| Structure of decision making with the partner | 0.20 (0.53) | 0.22 (0.53) | 0.09 (0.47) | 0.31 (0.57) | 1.84 | |||

| Type of DV in the last year | Psychological violence | Yes | 81.2 | 61.9 | 26.3 | 11.8 | 5.38 | |

| No | 18.8 | 77.8 | 20.0 | 2.2 | ||||

| Physical violence | Yes | 46.4 | 51.4 | 35.1 | 13.5 | 16.62 ** | ||

| No | 53.6 | 76.6 | 16.4 | 7.0 | ||||

| Economic violence | Yes | 20.0 | 70.8 | 20.8 | 8.4 | 1.03 | ||

| No | 80.0 | 63.0 | 26.1 | 10.9 | ||||

| Sexual violence | Yes | 18.4 | 47.7 | 40.9 | 11.4 | 7.90 * | ||

| No | 81.6 | 68.7 | 21.5 | 9.8 | ||||

| Physical injury due to DV | Yes | 20.0 | 29.2 | 56.2 | 14.6 | 36.09 ** | ||

| No | 80.0 | 73.4 | 17.2 | 9.4 | ||||

| Psychological suffering due to DV | Yes | 42.9 | 47.0 | 41.2 | 11.8 | 28.78 ** | ||

| No | 57.1 | 78.7 | 12.5 | 8.8 | ||||

| Felt intimidated or fearful due to DV | Yes | 44.8 | 44.9 | 43.9 | 11.2 | 39.54 ** | ||

| No | 55.2 | 81.1 | 9.8 | 9.1 | ||||

| C | Awareness of neighborhood and community | 2.60 (0.49) | 2.61 (0.49) | 2.63 (0.48) | 2.49 (0.56) | 0.75 | ||

| S | Attitude on gender roles | 2.25 (0.55) | 2.24 (0.54) | 2.36 (0.54) | 2.05 (0.58) | 2.99 | ||

| Attitude toward DV | 1.93 (0.39) | 1.94 (0.38) | 1.93 (0.40) | 1.84 (0.39) | 0.81 | |||

| Awareness of DV-related laws and policies | 0.61 (0.49) | 0.63 (0.32) | 0.62 (0.27) | 0.73 (0.27) | 1.27 | |||

| Awareness of DV-supporting facilities | 0.59 (0.30) | 0.58 (0.31) | 0.60 (0.29) | 0.66 (0.29) | 0.81 | |||

| Variable | Categories | Weighted % |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for “did nothing” at the time of DV (Priority order) | Only needed to endure the DV for the moment | 28.6 |

| He/she is my spouse | 21.9 | |

| Feeling ashamed | 16.1 | |

| If I respond, the violence gets worse | 15.1 | |

| Thinking of my child | 6.8 | |

| Thinking that it is my fault | 5.2 | |

| Feeling afraid | 5.1 | |

| Others | 1.3 | |

| Past experience of asking for external help | No | 79.6 |

| Yes | 20.4 | |

| External helper † (multiple choice allowed) | Family or relatives | 75.6 |

| Neighbors or friends | 64.0 | |

| Police | 11.7 | |

| Religious leaders | 8.1 | |

| Shelter for DV victims | 4.8 | |

| The 1366 hotline | 4.8 |

| IV | Escaped the Scene of Violence or Ran Outside | Became Reciprocally Violent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p | OR [95% CI] | p | |

| Age (ref. = 19–39 years) | ||||

| 40–59 | 1.52 [0.54–4.30] | 0.434 | 0.69 [0.24–1.98] | 0.489 |

| 60 or more | 2.05 [0.51–8.25] | 0.311 | 0.68 [0.09–4.90] | 0.701 |

| Education level (ref. = up to middle school graduates) | ||||

| High school graduates | 1.44 [0.50–4.13] | 0.498 | 4.67 [0.38–57.00] | 0.227 |

| College graduates or higher | 1.54 [0.39–6.04] | 0.537 | 10.47 [0.74–147.76] | 0.082 |

| Physical violence experience (ref. = none) | ||||

| Yes | 1.45 [0.68–3.11] | 0.336 | 2.32 [0.86–6.23] | 0.095 |

| Sexual violence experience (ref. = none) | ||||

| Yes | 3.22 [1.24–8.37] | 0.016 | 1.62 [0.48–5.50] | 0.437 |

| Physical injury (ref. = none) | ||||

| Yes | 3.08 [1.26–7.52] | 0.014 | 2.34 [0.68–8.11] | 0.179 |

| Psychological suffering (ref. = none) | ||||

| Yes | 1.40 [0.58–3.39] | 0.458 | 0.97 [0.31–3.03] | 0.955 |

| Felt intimidated or on fear (ref. = none) | ||||

| Yes | 5.44 [2.16–13.70] | <0.001 | 2.11 [0.67–6.67] | 0.202 |

| Attitude on gender roles | 1.41 [0.71–2.80] | 0.323 | 0.76 [0.31–1.84] | 0.543 |

| Awareness of DV related laws and policies | 0.60 [0.14–2.50] | 0.480 | 2.38 [0.36–15.54] | 0.366 |

| Awareness of DV supporting facilities | 2.56 [0.56–11.60] | 0.224 | 1.34 [0.22–8.25] | 0.751 |

| Cox and snell = 0.299, Negelkerke = 0.364, McFadden = 0.206 (p < 0.001) | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, Y.; Kim, H.; An, N. Factors Associated with Coping Behaviors of Abused Women: Findings from the 2016 Domestic Violence Survey. Healthcare 2022, 10, 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040622

Han Y, Kim H, An N. Factors Associated with Coping Behaviors of Abused Women: Findings from the 2016 Domestic Violence Survey. Healthcare. 2022; 10(4):622. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040622

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Youngran, Heejung Kim, and Nawon An. 2022. "Factors Associated with Coping Behaviors of Abused Women: Findings from the 2016 Domestic Violence Survey" Healthcare 10, no. 4: 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040622

APA StyleHan, Y., Kim, H., & An, N. (2022). Factors Associated with Coping Behaviors of Abused Women: Findings from the 2016 Domestic Violence Survey. Healthcare, 10(4), 622. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040622