“Dietitians May Only Have One Chance”—The Realities of Treating Obesity in Private Practice in Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Overview of Results

3.2.1. Patient-Centred Care Is Dietitians’ Preferred Intervention Model

D14 “It’s certainly not one size fits all. […] I think that for me, the most important thing (is) to have a good rapport with your patient, to let them know that you are walking the walk with them, that you’re not just sending them away with a regime.”

D13 “I try and get them to put in as much of the information as possible to try and find something that will work for them. […] So, I try and set goals with the patient that are almost set by them in a way.”

3.2.2. VLEDs Promote Weight Loss and Motivation

D16 “I probably have a 2 pronged approach. One is to just start that weight loss to get some motivation happening with people if they’ve constantly been failing, failing, failing to get a bit of motivation and weight down. The other thing is just to break that habit of reaching for food all the time, […] just to break that eating habit really.”

D4 “I’ve got to say, all my most memorable weight loss patients are the ones that have been on some kind of VLED and they’ve lost in excess of 20 kgs, 20, 30, 40, 50 kgs—I’ve never been able to achieve that kind of weight loss with just telling someone to cut back on their food.”

3.2.3. Experience Informed VLED Use

D3 “I mean it was a huge learning curve because it took me a long time to get my head around the fact that this was such an extreme measure but you know the results that we were seeing were really, really positive and the outcomes were really good, so I guess, you know that feeds back in, you know as a dietitian you know, you’re a scientist and so it’s nice to see those results.”

3.2.4. VLED Requires Long Term Involvement

D13 “I find most people who use shakes go back to their normal way of eating. [..] And by that time (going back to food) my EPCs (Enhanced Primary Care now known as CDM) have run out, and they may not or cannot continue as a private patient and I just can’t help them any further, it’s just sad. It’s one of the reasons why I decided not to practice as much anymore, because it was getting me down.”

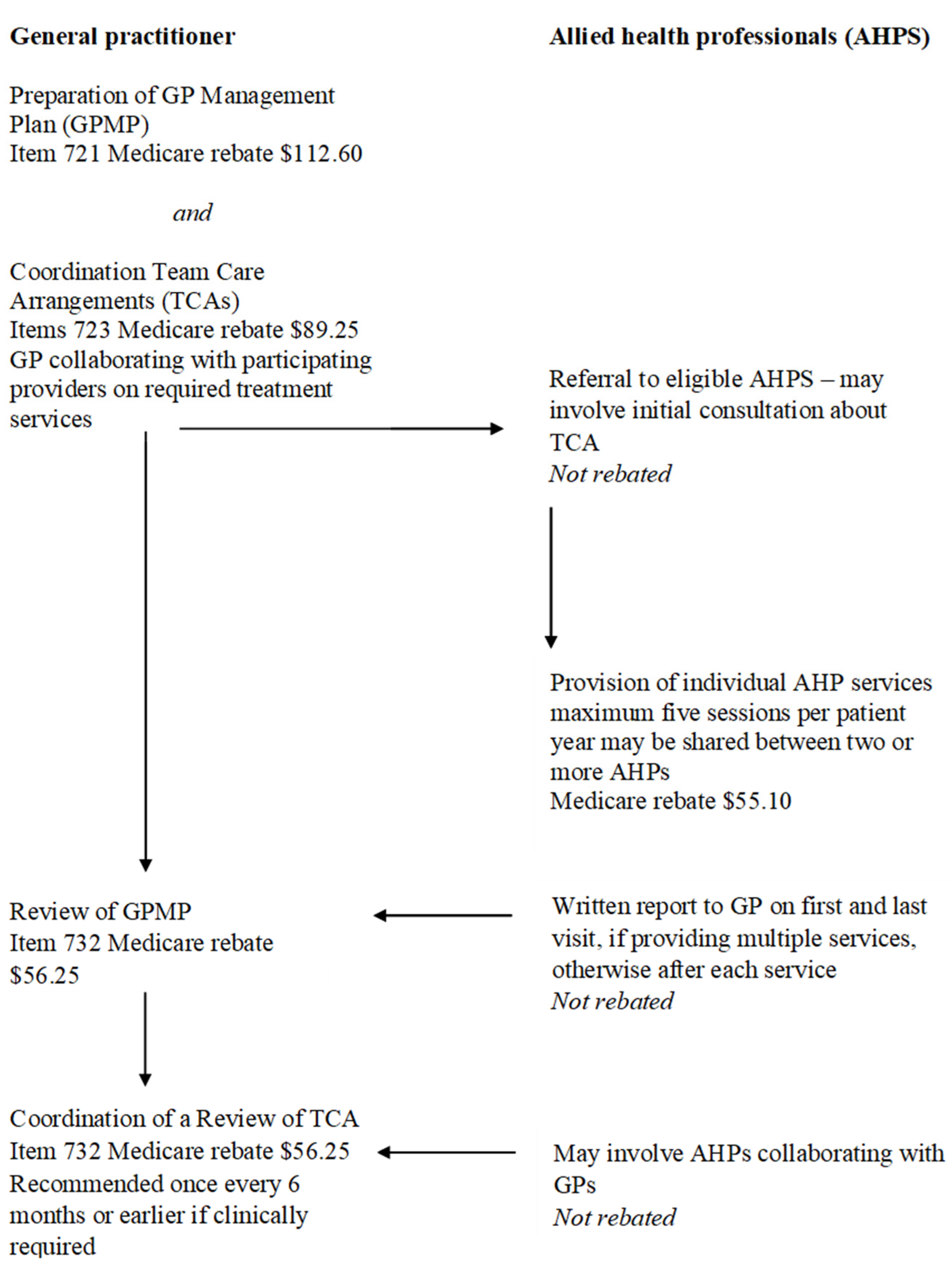

3.2.5. Systemic Barriers Constrain Effective Dietetic Practice

D9 “If we have evidence-based guidelines for overweight and obesity, which we do and we have frequency of contact that the evidence-based guidelines set out, which we do—would be to assess whether we can actually get that working in a public or even a private setting. You know, if we only have Medicare subsidisation for 5 dietetic sessions a year, how do we fit that in around all the evidence-based guidelines—I don’t think we can have Australian evidence-based guidelines and Australian funding models which aren’t consistent. We’ve got to try and streamline that, because how can people practice evidence-based guidelines otherwise?”

3.3. Medicare and CDM Scheme Limit Effective Dietetic Care

3.3.1. Insufficient Rebate through Medicare Could Cause Cutting Corners

D14 “In theory it (Medicare rebate scheme) should open up more possibilities, in theory it should open up more patients being able to come, but if we’re going to bulk bill them, it needs to be with a proper time frame and a proper payment, but the current system is just very messy and it doesn’t work. Medicare hasn’t done anything good for the profession sadly.”

3.3.2. Length of Consult Is Insufficient to Adequately Address Chronic Disease

D16 “What can you do in 20 min, really? A follow up maybe but you know even for that, especially if you’re doing a lifestyle intervention—you just can’t do that in 20 min. You have to build rapport to actually get some results and it’s just impossible to do.”

3.3.3. Number of Visits through Medicare Does Not Ensure Adequate Follow Up

D13 “If I’ve got 3 to 5 visits, I try and spread them out as much as I can without affecting what I think will be progress for them, you know if they’re spread out too much it doesn’t work either.” … “It’s just these people you’re seeing for short periods of time that you won’t see again until next year when they get another EPC and they’re back to where they were when you saw them for the very first time and that can be pretty demotivating for a practitioner, let alone for the patient themselves.”

3.4. Access to Health Information Makes Assessment and Treatment Goals Difficult

D11 “It would be wonderful (to have pathology), yeah, I mean that’s part of the reason why I’m weighing, is to see what kind of progress we’re making. Without having access to the pathology with the blood sugar or the cholesterol it’s hard to tell whether the weight loss is even having any difference to long term health. […] Having access to it would be really valuable.”

3.5. Successful Outcomes Are Predicated on Working Outside of Systemic Barriers

D11 “The person I was talking to you about just now who was really successful, I’ve seen her since January I think 6 times and that’s the kind of follow up you need, 6 times in 4 months and you know for the rest of the year she will see me less often because she’s doing great. So, if there was some sort of obesity programme where you can get 10 visits to a dietitian for a year I think that would make a really big difference, but I don’t know if there is scope for that, probably not.”

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VLED | Very Low Energy Diet |

| MRP | Meal Replacement Product |

| GPMP | General Practitioner Management Plan |

| CDM | Chronic Disease Management |

| EPC | Enhanced Primary Care |

| APD | Accredited Practicing Dietitian |

| MBS | Medical Benefits Scheme |

Appendix A

Appendix B. Invitation Email Sent to Dietitians

Appendix C. Recruitment via Dietitians Australia

Appendix D. APD Interviews—Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Appendix E

| No. Item | Guide Questions/Description | Reported on Page |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | ||

| Personal Characteristics | ||

| 1. Interviewer/facilitator | Which author/s conducted the inter view or focus group? | Page 3 CH |

| 2. Credentials | What were the researcher’s credentials? (e.g., PhD, MD). | Page 3 CH-APD+PhD Candidate JM − APD + Qual. AS & RVS-VLED researchers |

| 3. Occupation | What was their occupation at the time of the study? | Page 3 CH-APD+PhD Candidate |

| 4. Gender | Was the researcher male or female? | Page 1—Female |

| 5. Experience and training | What experience or training did the researcher have? | Page 3—CH-Previous Qual Honours project. JM-Qual researcher |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| 6. Relationship established | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? | Page 3 NIL relationship |

| 7. Participant knowledge of the interviewer | What did the participants know about the researcher? (e.g., personal goals, reasons for doing the research). | Page 3—Information sheet was provided during recruitment. |

| 8. Interviewer characteristics | What characteristics were reported about the interviewer/facilitator? (e.g. bias, assumptions, reasons and interests in the research topic). | Page 3—reasons study was done as a qualitative research study. |

| Domain 2: study design | ||

| Theoretical framework | ||

| 9. Methodological orientation and Theory | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? (e.g., grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis). | Page 3 & 4—Qualitative descriptive used with template analysis |

| Participant selection | ||

| 10. Sampling | How were participants selected? e.g. purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball | Page 3 |

| 11. Method of approach | How were participants approached? (e.g., face-to-face, telephone, mail, email). | Page 3 |

| 12. Sample size | How many participants were in the study? | Page 4 |

| 13. Non-participation | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? | Page 3 |

| Setting | ||

| 14. Setting of data collection | Where was the data collected? e.g. home, clinic, workplace | Page 3. |

| 15. Presence of non-participants | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? | Page 3 Inferred as one to one interviews |

| 16. Description of sample | What are the important characteristics of the sample? (e.g., demographic data, date). | Page 3, Page 4 and Table 1 |

| Data collection | ||

| 17. Interview guide | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? | Page 3 and Appendix C |

| 18. Repeat interviews | Were repeat inter views carried out? If yes, how many? | No, inferred on page 4 |

| 19. Audio/visual recording | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? | Page 3 |

| 20. Field notes | Were field notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? | Page 3 |

| 21. Duration | What was the duration of the inter views or focus group? | Page 3 |

| 22. Data saturation | Was data saturation discussed? | Page 3 |

| 23. Transcripts returned | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? | No |

| Domain 3: analysis and findings | ||

| Data analysis | ||

| 24. Number of data coders | How many data coders coded the data? | Page 3 & 4 |

| 25. Description of the coding tree | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? | Page 4 |

| 26. Derivation of themes | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? | Page 3 & 4 |

| 27. Software | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? | Page 3 & 4 |

| 28. Participant checking | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? | No |

| Reporting | ||

| 29. Quotations presented | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? (e.g., participant number). | Page 7 to 10 and Appendix F |

| 30. Data and findings consistent | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? | Yes, there was. Page 7 to 10 and Appendix F |

| 31. Clarity of major themes | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? | Yes. they were. From page 7 to 10 and Table 2. |

| 32. Clarity of minor themes | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? | Discussion of major and minor themes From page 7 to 10 and Appendix E |

Appendix F

| Major Themes | Additional Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1. Patient centred care is dietitians’ preferred intervention model | D10 “One size doesn’t fit all. […] So there are many tools available to us and I use the one that I think is most appropriate”. |

| 2. VLEDs promote weight loss in specific situations. | D1 “For some people it just kickstarts that weight loss, which then gives them the motivation to keep going”. D18 “I also feel that meal replacements can be appropriate if you match exactly the person for it so they know I’m just doing this until I get onto food and I just need some motivation, I just need the motivation that the weight drops down to see I’m getting results. And I can see the positive in that”. D7 “Yeah, really good (at complying to a VLED), I think because they can see the weight, as soon as they see that weight loss happening, they’re really motivated”. D10 “If that’s (food) not achieving the goals that the person has for whatever reason, then I’ll discuss VLED as an option”. D 13 “It’s (VLED) a tool, it’s another tool that I could use in a situation that I think will work or will work for that individual, yeah”. D8 “Any intervention where you get immediate results that helps motivate the person thereafter is going to be a good one and I do find that, if I get a diet history where there’s nothing jumping out saying this is why this person has put on 10 kgs over the last 6 months, I will usually pick the largest meal of the day and I will just replace that one meal with a meal replacement—they usually call me back and say ‘please let me do this for another week, this has been a real eye opener, I’m seeing results, I’m feeling better”. D15 “So as part of that language we use and the terminology we use is that VLCD- (Very Low Calorie Diet—alternative terminology for VLED)- is just a tool in our toolbox, so in the same way that we may start on that and we transition onto whatever is right for that person with the view that we’re helping to find something sustainable for them”. 2.1 Experience informed VLED use D4 “Because I was impressed that Mark Wahlqvist was using it(VLEDs) and Sharon Marks who’s another doctor, quite a well known obesity doctor, she did a lot with all her patients. So I said, well doctors are using it—dietitians should be all over it!” D15 “I think dietitians who have a heavy experience working with it couldn’t fail to notice that in fact, VLCDs do work better”. 2.2 Effective weight loss with VLED requires long term involvement D18 “Unless you know that person is locked into a programme where you’re going to get multiple additional connections and contact points to modify your coaching and nurture them and bring them along on the positive journey, but dietitians may only have one chance, that one consult or so because they may never come back, so you’ve got to consider that advice has to be stand alone”. |

| 3. Systemic barriers that constrain effective dietetic practice | 3.1 Medicare and CDM scheme limits effective dietetic care D9 “If the only way you can achieve evidence-based practice in Australia is somebody privately funding it themselves, you’re cutting out a huge proportion of the population who can’t afford that”. D16 ‘Obesity is such a massive problem, there’s a lot of evidence that it’s not a quick fix problem, it’s a long term, long slow weight loss is the more successful stuff through lifestyle intervention, so yeah, I think something’s got to change, but unfortunately it’s probably more likely to change for the negative, they’re more likely to take the Care Plans from us rather than give us more.’ D13 “They might not have the funds to then continue on as a private patient, a fee paying patient. It more often than not doesn’t happen. There’s so many people out there who, they need that extra help. There’s just so many people out there that can’t afford to see a dietitian and then they’re not going to get help”. D12 “We’re probably only seeing people with means, because there’s no way lower SES people are seeing dietitians on a regular basis, that’s not happening”. D10 “First and foremost, the obvious thing is Medicare coverage, I think the current system is absolutely absurd. Any idiot can tell you to be paying a GP to see someone for obesity when they don’t have the skills or the time is patently absurd”. 3.1.1 Insufficient rebate through Medicare could cause cutting corners D7 “I think we need the government to step up too—in terms of rebates. If a patient sees that there’s a gap well, number 1, they won’t go to the doctor—that’s number one. If they come to me there’s a big, you know, ummm, a bit of pressure on me to actually bulk bill the patient too, you know, even though the GP can charge a full fee”. 3.1.2 Length of consult is insufficient to adequately address chronic disease D13 “30 min—yeah—because it is a business and because there needs to be a certain amount of turnover, it’s 30 min. If it’s a private fee paying patient then I’ll allow 45 min for a new consult, but yeah, for an EPC (Enhanced Primary Care Plan), 30 min”. D14 “And there’s not the choice, I mean do you get a good reputation by doing something like that at your own expense? I have referrals, a lot of referrals of mine come from a practice that has a dietitian there. They have a bulk billing dietitian in their own practice and yet they prefer to refer out”. D10 “It’s not good for dietitians, because we need to spend a lot of time. It (EPCs) was built around 15–20 min consults which a physio can easily put through, but a dietitian, you can’t provide proper service. There’s a lot of new grads that are doing that because that’s the only way they can get work, so they can barely make ends meet. If it was working as it should it would be fantastic but it’s not”. 3.1.3 Number of visits through Medicare does not ensure adequate follow up D3 “Yeah, definitely it’s really hard to measure how effective you are. […] I don’t see them for enough sessions to know”. D7 “And you know maybe even increasing referrals—the sessions that we get and maybe specifically for dietitians—let’s up the ante for that, let’s make it ten instead of five—five is ridiculous—seriously”. D4 “I do offer, you know short appointments of 15 min to make it affordable and that’s only $xx to encourage them to keep coming back”. D 14 “Hopefully, if they have 5 visits in the year, I try to have, I mean obviously the first couple have to be pretty close together to check how they’re going and then obviously you’ve got to leave one. […] So I’ve got to save that one for a bit further down the track, so it’s very disappointing that you can’t follow it through. And being English, of course I believe in bulk billing, but you’ve got to get it right and they just haven’t got it right”. D19 ‘I get some people who do really, really well but it’s often in the short term and I don’t know how they go longer term after that, to be fair, they probably use up all their sessions within a 6 month period.’ D18 “But once again I suffer from—well, where do people go? What’s their journey? Have they put it all back on? |

| 3.2 Access to health information makes assessment and treatment goals difficult D18 “I would love to have access to some bloods and data, I’d love to know what’s happening with blood sugars, I’d love to know what’s happening with insulin, I’d love to know what’s happening with thyroid hormones and on occasion I’d love to know what’s happening with Vitamin D. All these things that particularly can have an influence […] but it’s just too hard to get”. D12 “It’s also getting that information sent from the GP to your office is quite difficult. So you would need them to go back, pick it up, because the doctor’s don’t email it”. D13 “There were some clinics that were a little bit private with that type of information and I was having to work off a laptop, which made it an absolute nightmare because the care plans would come in with do data on them whatsoever. The patients themselves don’t know their HbA1c or won’t know their cholesterol or what medications they’re taking. […] It was hard for me to know what they were when they just said a little blue pill and a little white pill, nuh, I can’t work with that unfortunately”. | |

| 4. Successful outcomes are predicated on working outside of systemic barriers | D13 “He came in and he said I want to lose 50 kgs and I said, ‘well that’s absolutely possible but it’s going to take some time.’ And he was fine with that and we just worked together over a 2.5 yr period to achieve that loss and the majority of it happened in the 1.5 yrs but it continued to happen over a longer period of time. A lot of the support toward the end was really just to make sure he was staying on track. So he felt if he kept these appointments it would keep him accountable to somebody and that was going to maintain the loss. […] Yeah, they’re paying out of their own pocket absolutely”. |

References

- World Health Organization. The Problem of Overweight and Obesity. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic; WHO Technical Report Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- The GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2013, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–2018; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2018; ABS 2018. Catalogue No. 4364.0.55.001. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/national-health-survey-first-results/latest-release. (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Impact of Overweight and Obesity as a Risk Factor for Chronic Conditions: Australian Burden of Disease Study; Australian Burden of Disease Study; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2017.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. Weighting the Cost of Obesity: A Case for Action. A Study on the Additional Costs of Obesity and Benefits of Intervention in Australia. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57e9ebb16a4963ef7adfafdb/t/580ebf681b631bede2b5f869/147736152015 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Haase, C.L.; Lopes, S.; Olsen, A.H.; Satylganova, A.; Schnecke, V.; McEwan, P. Weight loss and risk reduction of obesity-related outcomes in 0.5 million people: Evidence from a UK primary care database. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health Australian Government. Allied Health Services–Part A. Chronic Disease Management. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/03/askmbs-advisory-allied-health-services-part-a-chronic-disease-management.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Foster, M.M.; Mitchell, G.; Haines, T.; Tweedy, S.; Cornwell, P.; Fleming, J. Does Enhanced Primary Care enhance primary care? Policy-induced dilemmas for allied health professionals. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 188, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williamson, D.A.; Bray, G.A.; Ryan, D.H. Is 5% weight loss a satisfactory criterion to define clinically significant weight loss? Obesity 2015, 23, 2319–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parretti, H.M.; Jebb, S.A.; Johns, D.J.; Lewis, A.L.; Christian-Brown, A.M.; Aveyard, P. Clinical effectiveness of very-low-energy diets in the management of weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehackova, L.; Arnott, B.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Adamson, A.A.; Taylor, R.; Sniehotta, F.F. Efficacy and acceptability of very low energy diets in overweight and obese people with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Diabet. Med. 2016, 33, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Casazza, K.; Brown, A.; Astrup, A.; Bertz, F.; Baum, C.; Brown, M.B.; Dawson, J.; Durant, N.; Dutton, G.; Fields, D.A.; et al. Weighing the Evidence of Common Beliefs in Obesity Research. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 2014–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anderson, J.W.; Konz, E.C.; Frederich, R.C.; Wood, C.L. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: A meta-analysis of US studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrup, A.R.S. Lessons from obesity management programmes: Greater initial weight loss improves long-term maintenance. Obes. Rev. 2000, 1, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolland, C.; Johnston, K.L.; Lula, S.; Macdonald, I.; Broom, J. Long-term weight loss maintenance and management following a VLCD: A 3-year outcome. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2014, 68, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seimon, R.V.; Wild-Taylor, A.L.; McClintock, S.; Harper, C.; Gibson, A.A.; Johnson, N.A.; Fernando, H.A.; Markovic, T.P.; Center, J.R.; Franklin, J.; et al. 3-Year effect of weight loss via severe versus moderate energy restriction on body composition among postmenopausal women with obesity-the TEMPO Diet Trial. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.; Maher, J.; Grunseit, A.; Seimon, R.V.; Sainsbury, A. Experiences of using very low energy diets for weight loss by people with overweight or obesity: A review of qualitative research. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnoff, M.; Kaplan, L.M.; Shikora, S. An evidenced-based assessment of preoperative weight loss in bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2008, 18, 1059–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, C.G.A.; Williams, T. The bariatric surgery patient. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 42, 547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Liljensøe, A.; Laursen, J.O.; Bliddal, H.; Søballe, K.; Mechlenburg, I. Weight Loss Intervention Before Total Knee Replacement: A 12-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand. J. Surg. 2019, 110, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delbridge, E.; Proietto, J. State of the science: VLED (Very Low Energy Diet) for obesity. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 15, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, S.; Albert, M.; Kuper, A.; Hodges, B.D. Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ 2008, 337, a1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dietitians Australia. DAA Best Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Overweight & Obesity in Adults; Dietitians Association of Australia: Deakin, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C. Survey of dietetic management of overweight and obesity and comparison with best practice criteria. Nutr. Diet. J. Dietit. Assoc. Aust. 2003, 60, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, K. The Rate of Weight Loss Does Not Influence Long Term Weight Maintenance. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maston, G.; Franklin, J.; Gibson, A.A.; Manson, E.; Hocking, S.; Sainsbury, A.; Markovic, T.P. Attitudes and Approaches to Use of Meal Replacement Products among Healthcare Professionals in Management of Excess Weight. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014, 129, S102–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Department of Health. Primary Health Care in Australia. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/NPHC-Strategic-Framework~phc-australia (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Government. Primary Health Care. AIHW: Canberra, Australia. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/primary-health-care (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Siopis, G.; Jones, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The dietetic workforce distribution geographic atlas provides insight into the inequitable access for dietetic services for people with type 2 diabetes in Australia. Nutr. Diet. J. Dietit. Assoc. Aust. 2020, 77, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietitians Australia. Dietitians in the Private Sector Role Statement. Dietitians Australia. Available online: https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Primary-Care-Private-Practice-Role-Statement-2018.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Sandelowski, M.; Leeman, J. Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.S.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorafi, K.J.; Evans, B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. Herd 2016, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.; McCluskey, S.; Turley, E.; King, N. The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2015, 12, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health. 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care J. Int. Soc. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opie, C.A.; Haines, H.M.; Ervin, K.E.; Glenister, K.; Pierce, D. Why Australia needs to define obesity as a chronic condition. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission of Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient Centred Care: Improving Quality and Safety Through Partnerships with Patients and Consumers. Available online: www.safetyandquality.gov.au (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Sladdin, I.; Ball, L.; Bull, C.; Chaboyer, W. Patient-centred care to improve dietetic practice: An integrative review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.; Leeds, A.R. Very low-energy and low-energy formula diets: Effects on weight loss, obesity co-morbidities and type 2 diabetes remission–an update on the evidence for their use in clinical practice. Nutr. Bull. 2019, 44, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, R.; Slater, K.; Ball, L.; Jones, A.; Mitchell, L.; Rollo, M.E.; Williams, L.T. The tension between efficiency and effectiveness: A study of dietetic practice in primary care. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hutchesson, M.; Rollo, M.; Burrows, T.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Kerr, D.; Truby, H.; Clarke, E.; Collins, C.E. Current practice, perceived barriers and resource needs related to measurement of dietary intake, analysis and interpretation of data: A survey of Australian nutrition and dietetics practitioners and researchers. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 78, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, P.; Gorber, S.C.; Shaw, E.; Singh, H.; Bell, N.; Shane, A.R.E.; Jaramillo, A.; Tonelli, M. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care Recommendations for prevention of weight gain and use of behavioural and pharmacologic interventions to manage overweight and obesity in adults in primary care. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2015, 187, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, K.D.; Kahan, S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 102, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, Adolescents and Children in Australia. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/clinical-practice-guidelines-management-overweight-and-obesity (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- National Institute for Care and Excellence. Obesity: Identification, assessment and management (CG189). UK. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189 (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Holden, L.; Williams, I.; Patterson, E.; Smith, J.; Scuffham, P.; Cheung, L.; Chambers, R.; Golenko, X.; Weare, R. Uptake of Medicare chronic disease management incentives A study into service providers’ perspectives. Aust. Fam. Physician 2012, 41, 973–977. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson-Dunn, B. My Health Record: On a path to nowhere? Med. J. Aust. Insight 2018, 25. Available online: https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2018/25/my-health-record-on-a-path-to-nowhere/ (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Raza Khan, U.; Zia, T.A.; Pearce, C.; Perera, K. The MyHealthRecord System Impacts on Patient Workflow in General Practices. Stud Health Technol Inf. 2019, 266, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L.; Hemsley, B.; Allan, M.; Dahm, M.R.; Balandin, S.; Georgiou, A.; Higgins, I.; McCarthy, S.; Hill, S. Assessing the information quality and usability of My Health Record within a health literacy framework: What’s changed since 2016? Health Inf. Manag. J. Health Inf. Manag. Assoc. Aust. 2021, 50, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hancock, R.E.; Bonner, G.; Hollingdale, R.; Madden, A.M. ‘If you listen to me properly, I feel good’: A qualitative examination of patient experiences of dietetic consultations. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. Off. J. Br. Diet. Assoc. 2012, 25, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gearon, E.; Backholer, K.; Lal, A.; Nusselder, W.; Peeters, A. The case for action on socioeconomic differences in overweight and obesity among Australian adults: Modelling the disease burden and healthcare costs. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ball, K.; Crawford, D. Socio-economic factors in obesity: A case of slim chance in a fat world? Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 15, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dietitians Australia. DAA Pre-Budget Submission 2018/19; DAA: Sydney, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/DAA-Pre-Budget-Submission-Jan-2018.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Allied Health Professionals Australia. Recommendations to the Medicare Benefits Schedule Review Allied Health Reference Group; AHPA: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://ahpa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/180719-MBS-Review-Framework.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Medical Benefits Schedule Review Taskforce. Post Consultation Report from Allied Health Reference Group; Australian Government, Department of Health. 2019. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/06/final-report-from-the-allied-health-reference-group.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Medical Benefits Schedule Review Taskforce. Report on Primary Care; Australian Government, Department of Health. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/12/taskforce-final-report-primary-care-report-on-primary-care.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Clark, P.W.; Williams, L.T.; Kirkegaard, A.; Brickley, B.; Ball, L. Perceptions of private practice dietitians regarding the collection and use of outcomes data in primary healthcare practices: A qualitative study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 35, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.T.; Barnes, K.; Ball, L.; Ross, L.J.; Sladdin, I.; Mitchell, L.J. How Effective Are Dietitians in Weight Management? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Healthcare 2019, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ash, S.; Reeves, M.; Bauer, J.; Dover, T.; Vivanti, A.; Leong, C.; Sullivan, T.O.M.; Capra, S. A randomised control trial comparing lifestyle groups, individual counselling and written information in the management of weight and health outcomes over 12 months. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnston, H.J.; Jones, M.; Ridler-Dutton, G.; Spechler, F.; Stokes, G.S.; Wyndham, L.E. Diet modification in lowering plasma cholesterol levels. A randomised trial of three types of intervention. Med. J. Aust. 1995, 162, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.J.; Ball, L.E.; Ross, L.J.; Barnes, K.A.; Williams, L.T. Effectiveness of Dietetic Consultations in Primary Health Care: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1941–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Dietitian | Years of Experience | Private Practice and/or GP or Other Specialist Practice | Private Bariatric Surgery | Public Health, Community, Hospital or Private Hospital | Research | Commercial, Industry and/or Health Fund Programme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 2 | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3 | 18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4 | 30 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5 | 51 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6 | 43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8 | 13 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9 | 19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10 | 25 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 11 | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 12 | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13 | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 14 | 25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 15 | 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 16 | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 17 | 28 | ✓ | ||||

| 18 | 25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 19 | 15 | ✓ | ||||

| 20 | 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Major Themes | Explanatory Subthemes |

|---|---|

| 1. Patient centred care is dietitians’ preferred intervention model | |

| 2. VLEDs promote weight loss in specific situations. | 2.1 Experience informed VLED use and 2.2 VLED requires long term involvement. |

| 3. Systemic barriers that constrain effective dietetic practice | 3.1 Medicare and CDM scheme limits effective dietetic care. 3.1.1 Insufficient rebate through Medicare could cause cutting corners 3.1.2 Length of consult is insufficient to adequately address chronic 3.1.3 Number of visits through Medicare does not ensure adequate follow up. |

| 3.2 Poor access to health information makes assessment and treatment goals difficult. | |

| 4. Successful outcomes are predicated on working outside of systemic barriers |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harper, C.; Seimon, R.V.; Sainsbury, A.; Maher, J. “Dietitians May Only Have One Chance”—The Realities of Treating Obesity in Private Practice in Australia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020404

Harper C, Seimon RV, Sainsbury A, Maher J. “Dietitians May Only Have One Chance”—The Realities of Treating Obesity in Private Practice in Australia. Healthcare. 2022; 10(2):404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020404

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarper, Claudia, Radhika V. Seimon, Amanda Sainsbury, and Judith Maher. 2022. "“Dietitians May Only Have One Chance”—The Realities of Treating Obesity in Private Practice in Australia" Healthcare 10, no. 2: 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020404

APA StyleHarper, C., Seimon, R. V., Sainsbury, A., & Maher, J. (2022). “Dietitians May Only Have One Chance”—The Realities of Treating Obesity in Private Practice in Australia. Healthcare, 10(2), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020404