Social Stigma of Patients Suffering from COVID-19: Challenges for Health Care System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Isolating a difference and giving a label to the person affected by that difference;

- Linking isolated social categories to negative stereotypes;

- Separating “us” from “them”—negative stereotyping, influences rejection, exclusion and discrimination;

2. Methods

3. Results

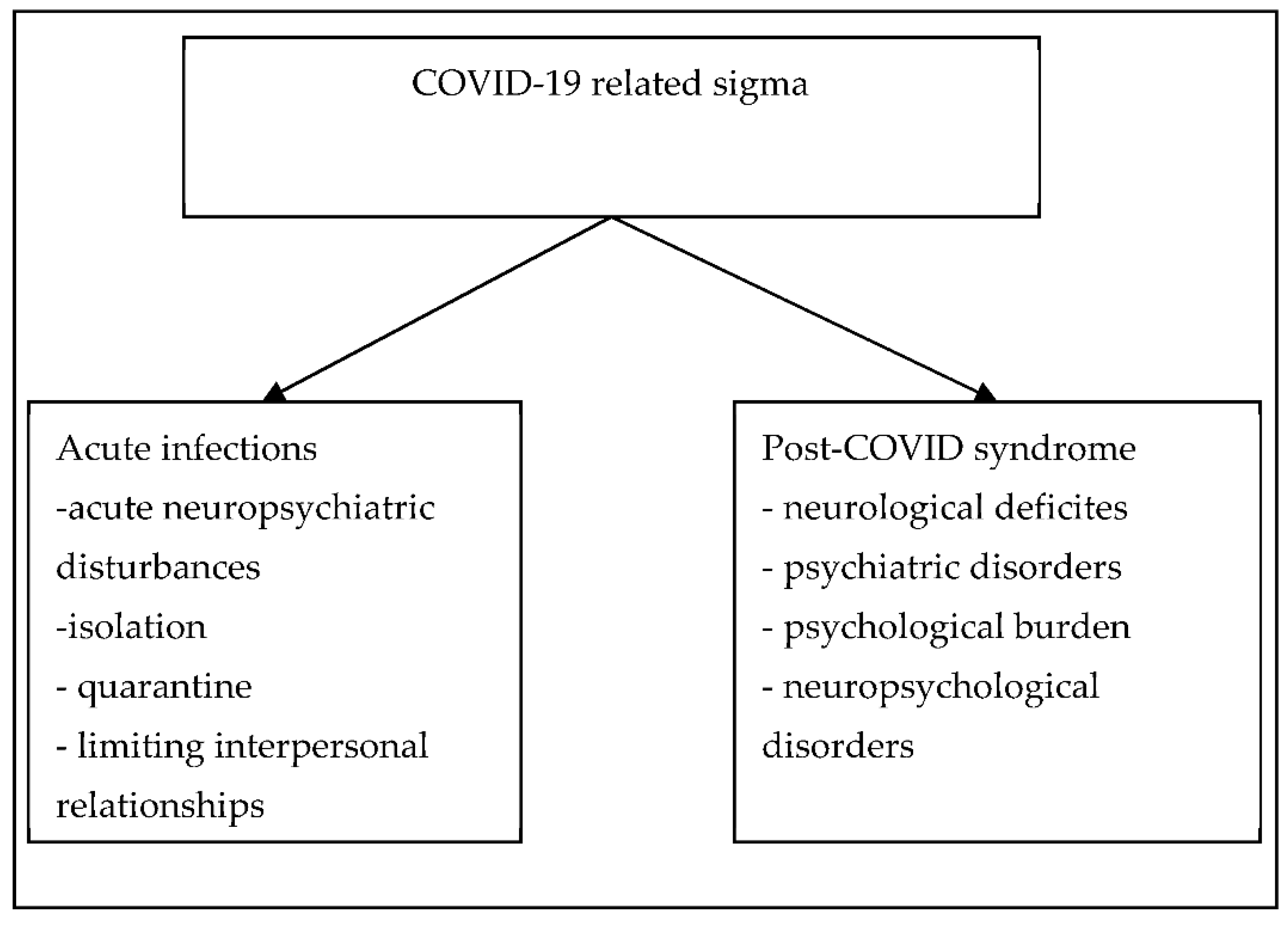

3.1. Stigma and COVID-19

3.2. COVID-19 and Comorbidities

3.3. Factors Determining the Stigma of People with COVID-19

3.4. Consequences of Stigmatization Due to COVID-19

3.5. Specific Antistigma Interventions and Strategies

- Identify factors associated with stigma

- Identify dominant forms of stigma

- Develop action plan to help address factors associated with stigma and forms of stigma.

- a.

- Education on stigma

- b.

- Provision of personal protective equipment by hospital management

- c.

- Training in the management of COVID-19 for cadre of health staff

- d.

- Avoiding marking beds or wards with “COVID-19”

- e.

- Develop a disciplinary panel for health care workers who stigmatize despite training

- f.

- Conducting systematic training on the management of an infectious disease with

- g.

- The potential for global spread

- h.

- Conducting an anti-stigma campaign for all forms of infectious diseases.

- Identify factors associated with stigma

- Identify dominant forms of stigma

- Develop action plan to help address factors associated with stigma and forms of stigma.

- a.

- Train the media to ensure ethical journalism

- b.

- Identify and correct myths and misinformation

- c.

- Celebrate memorial days and COVID-19 heroes

- d.

- Use social influencers

- e.

- Provide accurate and up to date information concerning COVID-19

- f.

- Infomercials on COVID-19 should not focus on any particular ethnic or racial group and should be produced in partnership with public figures and celebrities

- g.

- Provide regular broadcasted messages on infectious disease with potential for global spread

- h.

- Highlight strengths and positive aspects of the country when providing updates on COVID-19

- i.

- Put policies in place to help citizens recover from the socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic.

- Identify and respond to the needs of the stigmatized population.

- a.

- Identify factors associated with stigma

- b.

- Identify forms of stigma.

- ▪

- Ensure confidentiality when requested

- ▪

- Provide policies on accessing healthcare post pandemic

- ▪

- Provide psychosocial support

- ▪

- Support victims of stigma

- ▪

- Make healthcare readily accessible and widely available.

3.6. List of Major Challenges for the Health Care System in the Era of COVID-19

- Systematic training of health professionals to assist in the assessment and treatment of people affected by stigma.

- The establishment of a psychological support network for health workers who are at increased risk of COVID-19related stigma.

- Implementation of medical IT systems for online patient services (allowing video calls, among other things, psychological support for people who have experienced stigma or discrimination).

- To develop educational material for patients and the general public on how to combat stigma.

- Providing information from reliable sources to increase knowledge and reduce stigma associated with COVID-19.

- Improving access to support and health care

- Maintaining the confidentiality and privacy of those seeking healthcare.

- Correcting negative language that can cause stigma.

- Speaking out against negative statements and behaviors.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Prentice-Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Rewerska-Juśko, M.; Rejdak, K. Social stigma of people with dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 78, 1339–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackowska, E. Stigma and discrimination towards people with schizophrenia—A survey of studies and psychological mechanisms. Psychiatr. Pol. 2009, 43, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Świtaj, P. Experience of Socialstigma and Discrimination in Patients Diagnosed with Schizophrenia; Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, T.M.; Wang, J.L. Descriptive epidemiology of sigma against depression in a general population sample in Alberta. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stephan, W.G.; Stephan, C.W. Influencing groups. In Relationship Psychology; GWP: Gdańsk, German, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paleari, F.G.; Pivetti, M.; Galati, D.; Fincham, F.D. Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: The role of stigma and appraisals. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, A.L.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Logie, C.H.; van Brakel, W.; Simbayi, L.C.; Barr´e, I.; Dovidio, J.F. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, S.P.; Stier, A. Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mascayano, F.; Tapia, T.; Schilling, S.; Alvarado, R.; Tapia, E.; Lips, W.; Yang, L.H. Stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2016, 38, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ginsburg, I.H.; Bruce, G. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1989, 20, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfo, F.S.; Nichols, M.; Qanungo, S.; Teklehaimanot, A.; Singh, A.; Mensah, N.; Saulson, R.; Gebregziabher, M.; Ezinne, U.; Owolabi, M.; et al. Stroke-related sigma among West Africans: Patterns and predictors. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 375, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Earnshaw, V. Don’t Let the Fear of COVID-19 turn into Stigma. Economics and Society. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/04/dont-let-fearof-covid-19-turn-into-stigma (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Bhanot, D.; Singh, T.; Verma, S.K.; Shivantika-Sharad, S. Stigma and Discrimination During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M. Experiencing and coping with social stigma. In APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology: GroupProcesses; Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 473–506. [Google Scholar]

- Link, B.G.; Cullen, F.T. Reconsidering the social lrejection of ex mental patients: Levels of attitudeinal response. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1983, 11, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.E.; Kumar, S.; Rajji, T.K.; Pallock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H. Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, G. Alzheimer’s disease patients in the crosshairs of COVID-19. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 76, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Barbarino, P.; Gauthier, S.; Brodaty, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, E.; Tang, Y.; et al. Dementia careduring COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.; Schwarzkopf, L.; Graessel, E.; Holle, R. A claims data-basedcomparison of comorbidity in individuals with and without dementia. BMC Geriatrics 2014, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Sahebari, S.S.; Naser, A. Dementia and COVID-19: Complications of managing a pandemic during another pandemic. Dement. Neuropsycho. 2020, 14, 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotuhia, M.; Mianc, A.; Meysamid, S.; Rajic, C.A. Neurobiology of COVID-19. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IANS. COVID-19: Indians From the North East Region Victims of Racial and Regional Prejudice. The News Scroll. Available online: https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/covid19-indians-fromthe-north-east-regionvictims-of-racial-and-regional-prejudice/1844685 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Chanu, O.M.; Sharad, S. A study of inter-group perception and experience of northeasterners (NE) of India. Defence Life Sci. J. 2020, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colney, K. Indians From the Northeast Face Intensified Racism as Coronavirus Fears Grow. The Caravan. Available online: https://caravanmagazine.in/communities/coronavirus-increases-racism-againstindians-from-northeast (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Kalichman, S. Understanding AIDS, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.N.; Smith, B.L. Deaths: Leading causes for 2002. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2005, 53, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan, H.; Jha, D.N.; Sharda, S.; Rao, S.; PS, S.; Iyer, M. Why You Need to Clap for India’s Healthcare Workers. Sunday Times India 2020, 23, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sastry, A.K. Recovered COVID-19 Shares His Experience. The Hindu. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Mangalore/recovered-covid-19-patient-shares-his-experience/article31394243.ece (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Ankur, K.; Erin, D.M.; Kavitha, M.C. COVID-19 and the healthcare workers. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2936–2937. [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, C. Coronavirus in India: How Cops Are Fighting Covid-19 Surge in Ranks. India Today. Available online: https://www.indiatoday.in/mail-today/story/coronavirus-in-india-how-cops-are-fighting-covid-19-surge-in-ranks-1668562-2020-04-19 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- IANS. Woman Constable Dies of Coronavirus, 3 Days after Giving Birth to Baby. Available online: https://www.indiatvnews.com/news/india/woman-constable-dies-of-coronavirus-3-days-after-givingbirth-to-baby-614900 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Pandey, A. Will See Baby Girl after Lockdown Ends, Duty First, Says Constable. NDTV. Available online: https://www.ndtv.com/indianews/coronavirus-duty-above-brand-new-baby-girl-says-this-coronawarrior-in-up-2211663 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Times News Network. Health Team Attacked in Indore During Screening. Times of India. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/health-team-attacked-in-indore-during-screening/articleshow/74940167.cms (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Times News Network. Coronavirus: After Taali-Thaali, Health Workers Face Social Stigma. The Times of India City. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/coronavirus-after-taali-thaalihealth-workers-face-social-stigma/articleshow/74801988.cms (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Kaushik, J. Chennai Residents Oppose Doctor’s Cremation, Attack Hospital Staff. The Indian Express. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/chennai/covid-death-chennai-residents-opposeddoctors-cremation-ransack-ambulance-6370917/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Hannah, E.P.; Shaikh, A.R. Indian Doctors Being Evicted from Homes Over Coronavirus Fears. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/30/indian-doctors-being-evicted-fromhomes-over-coronavirus-fears (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Frost, D.M. Social stigma and its consequences for the socially stigmatized. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2011, 5, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIFRC, UNICEF, WHO. Social Stigma Associated with COVID-19: A Guide to Preventing and Addressing Social Stigma. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid19-stigmaguide.pdf?sfvrsn=226180f4_2 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- The Economic Times. Do Not Label Any Community or Area for Spread of COVID-19: Government. The Economic Times Press Trust of India. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimescom/news/politics-and-nation/do-not-label-any-community-or-area-for-spread-of-covid-19government/articleshow/75051453.cms (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- UNICEF. Social Sigma Associated with the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/65931/file/Social%20stigma%20associated%20with%20the%20coronavirus%20disease%202019%20(COVID-19).pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Krishnan, M. Indian Muslims Face Renewed stigma Amid COVID-19 Crisis. Deutsche Welle: Made for Minds. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/covid-19.html (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Press Trust of India. Tabligh Members Undergoing Treatment Not Cooperating: Doctors to Delhi govt. The Economic Times. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/tabligh-membersundergoing-treatment-not-cooperating-doctorstodelhigovt/articleshow/74969727.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Ghosal, A.; Saaliq, S.; Schmall, E. Indian Muslims Face Stigma, Blame for Surge in Infections. Associated Press News. Available online: https://apnews.com/ad2e96f4caa55b817c3d8656bdb2fcbd (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Wileya, K.E.; Leaskab, J.; Attwell, K.; Helps, C.; Barclay, L.; Warde, P.R.; Carterf, S.M. Stigmatized for standing up for my child: A qualitative study of non-vaccinating parents in Australia. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 16, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, M.G.; Ramakrishna, J.; Somma, D. Health-related stigma: Rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 11, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usher, K.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Gyamfi, N.; Jackson, D. Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int. J. Mental Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, R.A.; Hughes, D. Infectious desease stigmas: Maladaptive In modern socjety. Commun. Stud. 2014, 65, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villa, S.; Jaramillo, E.; Davide, M.; Bandera, A.; Gori, A.; Raviglione, M.C. Stigma at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1450–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostman, M.; Kjellin, L. Stigma by association: Psychological factors in relatives of people with mental illness. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 181, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Times of India. Madurai: Stigma over Coronavirus Testing Blamed for Man’s Suicide. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/madurai/stigma-over-covid-testing-blamed-for-mans-suicide/articleshow/74939681.cms (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Adiukwu, F.; Bytyçi, D.G.; Hayek, S.L.; Gonzalez-Diaz, J.M.; Amine Larnaout, A.; Grandinetti, P.; Nofal, M.; Victor Pereira-Sanchez, V.; Ransing, R.; Shalbafan, M.; et al. Global Perspective and Ways to Combat Stigma Associated with COVID-19. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Pakrashi, D.; Vlassopoulos, M.; Wang, L.C. Stigma and misconceptions in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: A field experiment in India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 278, 113966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; Zhang, Q.E.; Zhang, L.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Jiang, G.Q.; Xiang, Y.T. COVID-19-related stigma and its sociodemographic correlates: A comparative study. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadivel, R.; Shoib, S.; El Halabi, S.; El Hayek, S.; Essam, L.; Gashi, B.D.; Karaliuniene, R.; Schuh Teixeira, A.L.; Nagendrappa, S.; Ramalho, R.; et al. Mental health in the post-COVID-19 era: Challenges and the way forward. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 34, e100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rewerska-Juśko, M.; Rejdak, K. Social Stigma of Patients Suffering from COVID-19: Challenges for Health Care System. Healthcare 2022, 10, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020292

Rewerska-Juśko M, Rejdak K. Social Stigma of Patients Suffering from COVID-19: Challenges for Health Care System. Healthcare. 2022; 10(2):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020292

Chicago/Turabian StyleRewerska-Juśko, Magdalena, and Konrad Rejdak. 2022. "Social Stigma of Patients Suffering from COVID-19: Challenges for Health Care System" Healthcare 10, no. 2: 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020292

APA StyleRewerska-Juśko, M., & Rejdak, K. (2022). Social Stigma of Patients Suffering from COVID-19: Challenges for Health Care System. Healthcare, 10(2), 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020292