Current Considerations in Surgical Treatment for Adolescents and Young Women with Breast Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

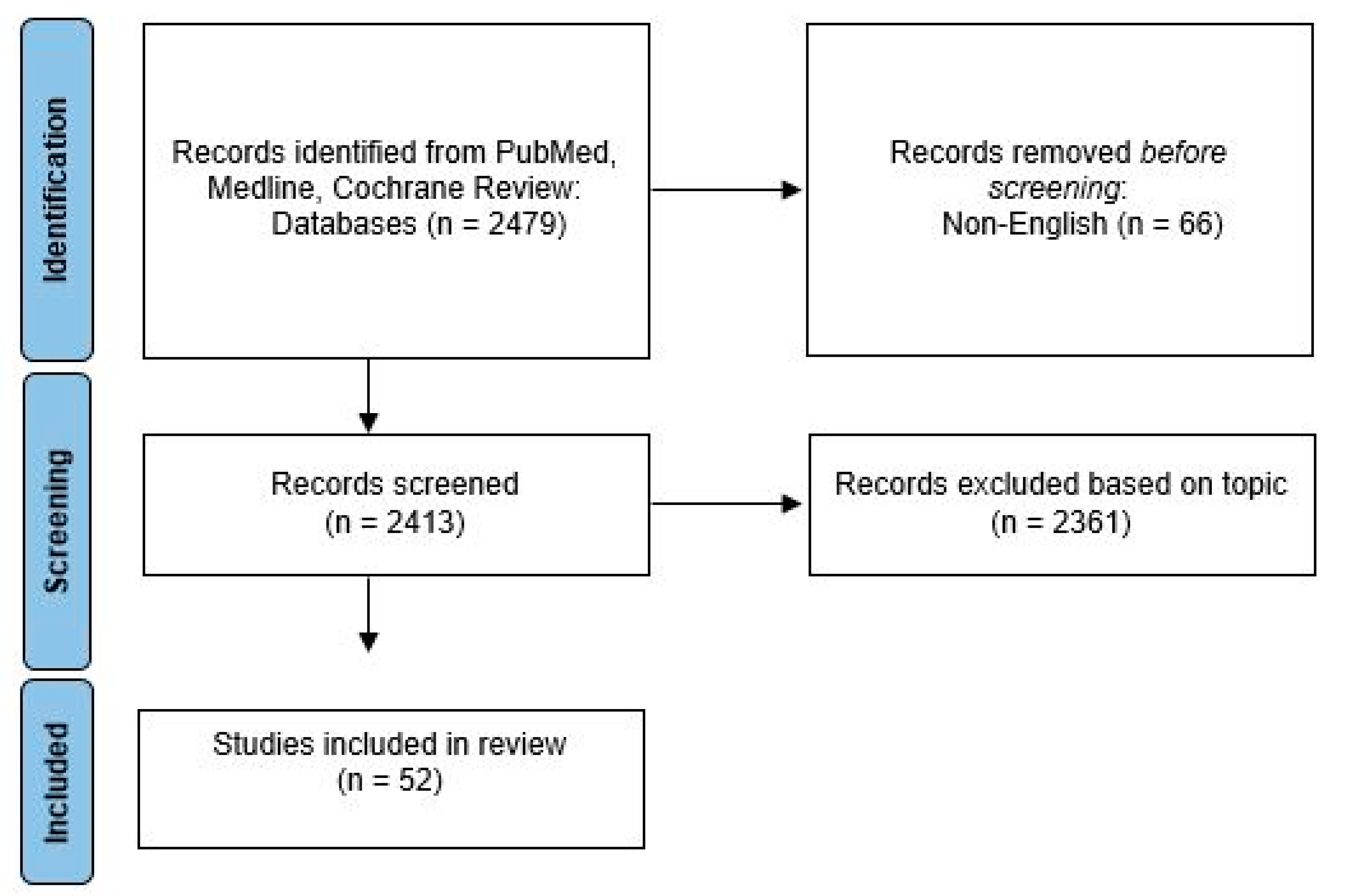

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Breast Surgical Procedure

3.2. Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy

3.3. Axillary Surgery

3.4. Time to Treatment

3.5. Psychological Effects of Surgery

3.6. Disparities

3.7. Imaging

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cathcart-Rake, E.J.; Ruddy, K.J.; Bleyer, A.; Johnson, R.H. Breast Cancer in Adolescent and Young Adult Women Under the Age of 40 Years. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.H.; Anders, C.K.; Litton, J.K.; Ruddy, K.J.; Bleyer, A. Breast cancer in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: Collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet 1996, 347, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: Individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadeau, C.; Fournier, A.; Mesrine, S.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Fagherazzi, G.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C. Postmenopausal breast cancer risk and interactions between body mass index, menopausal hormone therapy use, and vitamin D supplementation: Evidence from the E3N cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 2193–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clamp, A.; Danson, S.; Clemons, M. Hormonal risk factors for breast cancer: Identification, chemoprevention, and other intervention strategies. Lancet Oncol. 2002, 3, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierisch, J.M.; Coeytaux, R.R.; Urrutia, R.P.; Havrilesky, L.J.; Moorman, P.G.; Lowery, W.J.; Dinan, M.; McBroom, A.J.; Hasselblad, V.; Sanders, G.D.; et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of breast, cervical, colorectal, and endometrial cancers: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013, 22, 1931–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.O.; Amsterdam, A.; Bhatia, S.; Hudson, M.M.; Meadows, A.T.; Neglia, J.P.; Diller, L.R.; Constine, L.S.; Smith, R.A.; Mahoney, M.C.; et al. Systematic review: Surveillance for breast cancer in women treated with chest radiation for childhood, adolescent, or young adult cancer. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, C.S.; Chou, J.F.; Wolden, S.L.; Bernstein, J.L.; Malhotra, J.; Novetsky Friedman, D.; Mubdi, N.Z.; Leisenring, W.M.; Stovall, M.; Hammond, S.; et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2217–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Oestrogen exposure and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. 2003, 5, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, L.A.; Trabert, B.; Shalev, V.; Lunenfeld, E.; Sella, T.; Chodick, G. In vitro fertilization and risk of breast and gynecologic cancers: A retrospective cohort study within the Israeli Maccabi Healthcare Services. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergentanis, T.N.; Diamantaras, A.A.; Perlepe, C.; Kanavidis, P.; Skalkidou, A.; Petridou, E.T. IVF and breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Belt-Dusebout, A.W.; Spaan, M.; Lambalk, C.B.; Kortman, M.; Laven, J.S.; van Santbrink, E.J.; van der Westerlaken, L.A.; Cohlen, B.J.; Braat, D.D.; Smeenk, J.M.; et al. Ovarian Stimulation for In Vitro Fertilization and Long-term Risk of Breast Cancer. JAMA 2016, 316, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn, A.; Watson, L.; Lumley, J.; Giles, G.; King, C.; Healy, D. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence after infertility and in vitro fertilisation. Lancet 1995, 346, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilini, P.A.; Pagani, O. (Eds.) Breast Cancer in Young Women; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.F.; Guo, H.; Martin, L.J.; Sun, L.; Stone, J.; Fishell, E.; Jong, R.A.; Hislop, G.; Chiarelli, A.; Minkin, S.; et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, W.D.; Parl, F.F.; Hartmann, W.H.; Brinton, L.A.; Winfield, A.C.; Worrell, J.A.; Schuyler, P.A.; Plummer, W.D. Breast cancer risk associated with proliferative breast disease and atypical hyperplasia. Cancer 1993, 71, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Sellers, T.A.; Frost, M.H.; Lingle, W.L.; Degnim, A.C.; Ghosh, K.; Vierkant, R.A.; Maloney, S.D.; Pankratz, V.S.; Hillman, D.W.; et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Freedman, R.A.; Partridge, A.H. Management of breast cancer in very young women. Breast 2013, 22 (Suppl. 2), S176–S179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeffinger, K.C.; Fontham, E.T.; Etzioni, R.; Herzig, A.; Michaelson, J.S.; Shih, Y.C.; Walter, L.C.; Church, T.R.; Flowers, C.R.; LaMonte, S.J.; et al. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society. JAMA 2015, 314, 1599–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.M.; Partridge, A.H. Management of breast cancer in very young women. Breast 2015, 24 (Suppl. 2), S154–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.L.; Day, C.N.; Hoskin, T.L.; Habermann, E.B.; Boughey, J.C. Adolescents and Young Adults with Breast Cancer have More Aggressive Disease and Treatment Than Patients in Their Forties. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 3920–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilewskie, M.; King, T.A. Age and molecular subtypes: Impact on surgical decisions. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 110, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.H.; Chen, C.; Kuang, X.W.; Song, J.L.; Sun, S.R.; Wang, W.X. Breast surgery for young women with early-stage breast cancer: Mastectomy or breast-conserving therapy? Medicine 2021, 100, e25880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.C.; Yan, W.; Christos, P.J.; Nori, D.; Ravi, A. Equivalent Survival With Mastectomy or Breast-conserving Surgery Plus Radiation in Young Women Aged <40 Years With Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A National Registry-based Stage-by-Stage Comparison. Clin. Breast Cancer 2015, 15, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Tang, H.; Zou, Y.; Liu, P.; Tian, W.; Zhang, K.; Xie, X.; Ye, F. Breast-Conserving Therapy Versus Mastectomy in Young Breast Cancer Patients Concerning Molecular Subtypes: A SEER Population-Based Study. Cancer Control 2020, 27, 1073274820976667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.J.; Liu, Y.Y.; Hu, X.; Di, G.H. Survival following breast-conserving therapy is equal to that following mastectomy in young women with early-stage invasive lobular carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1703–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.J.; Wu, S.P.; Nagar, H.; Gerber, N.K. Ductal Carcinoma in Situ in Young Women: Increasing Rates of Mastectomy and Variability in Endocrine Therapy Use. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 6083–6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazow, S.P.; Riba, L.; Alapati, A.; James, T.A. Comparison of breast-conserving therapy vs mastectomy in women under age 40: National trends and potential survival implications. Breast J. 2019, 25, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, J.I.J.; Keller, J.K.; Chang, S.C.; Fancher, C.E.; Grumley, J.G. Impact of Locoregional Treatment on Survival in Young Patients with Early-Stage Breast Cancer undergoing Upfront Surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 6299–6310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, C.; Liederbach, E.; Czechura, T.; Winchester, D.J.; Yao, K. Changing surgical trends in young patients with early stage breast cancer, 2003 to 2010: A report from the National Cancer Data Base. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014, 219(1), 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, C.E.; Park, H.S.; Killelea, B.K.; Evans, S.B. Growing Use of Mastectomy for Ductal Carcinoma-In Situ of the Breast Among Young Women in the United States. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 2378–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Dominici, L.; Rosenberg, S.M.; Zheng, Y.; Pak, L.M.; Poorvu, P.D.; Ruddy, K.J.; Tamimi, R.; Schapira, L.; Come, S.E.; et al. Surgical Treatment After Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy in Young Women With Breast Cancer: Results from a Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. 2022, 276, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.M.; Zou, D.H. The association of young age with local recurrence in women with early-stage breast cancer after breast-conserving therapy: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, J.C.; Liu, W.S.; Huang, W.T.; Shih, L.C.; Liu, W.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Chou, K.J.; Shiue, Y.L.; Lin, P.C. Local treatment options for young women with ductal carcinoma in situ: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing breast conserving surgery with or without adjuvant radiotherapy, and mastectomy. Breast 2022, 63, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, J.; Gandini, S.; Gentilini, O. Overall survival according to type of surgery in young (≤40 years) early breast cancer patients: A systematic meta-analysis comparing breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy. Breast 2015, 24, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, P.A.; Olcese, C.; Patil, S.; Morrow, M.; Van Zee, K.J. Impact of Age on Risk of Recurrence of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: Outcomes of 2996 Women Treated with Breast-Conserving Surgery Over 30 Years. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 23, 2816–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; He, G. Comparing the Prognoses of Breast-Conserving Surgeries for Differently Aged Women with Early Stage Breast Cancer: Use of a Propensity Score Method. Breast J. 2022, 2022, 1801717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.Q.; Truong, P.T.; Olivotto, I.A.; Olson, R.; Coulombe, G.; Keyes, M.; Weir, L.; Gelmon, K.; Bernstein, V.; Woods, R.; et al. Should women younger than 40 years of age with invasive breast cancer have a mastectomy? 15-year outcomes in a population-based cohort. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014, 90, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Chang, Y.J.; Chang, Y.J. Treatment and long-term outcome of breast cancer in very young women: Nationwide population-based study. BJS Open 2021, 5, zrab087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, J.; Ly, D.; Cannon, G.; Suneja, G.; Matsen, C.; Gaffney, D.K.; Wright, M.; Kokeny, K.E.; Poppe, M.M. In the Modern Treatment Era, Is Breast Conservation Equivalent to Mastectomy in Women Younger Than 40 Years of Age? A Multi-Institution Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 93, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.W.; Choi, J.E.; Park, H.K.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Suh, Y.J. Impact of local surgical treatment on survival in young women with T1 breast cancer: Long-term results of a population-based cohort. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 138, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maishman, T.; Cutress, R.I.; Hernandez, A.; Gerty, S.; Copson, E.R.; Durcan, L.; Eccles, D.M. Local Recurrence and Breast Oncological Surgery in Young Women With Breast Cancer: The POSH Observational Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. 2017, 266, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, M.L.; Paszat, L.F.; Fernandes, K.A.; Sutradhar, R.; McCready, D.R.; Rakovitch, E.; Warner, E.; Wright, F.C.; Hodgson, N.; Brackstone, M.; et al. The effect of surgery type on survival and recurrence in very young women with breast cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 115, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnadurai, S.; Kwong, A.; Hartman, M.; Tan, E.Y.; Bhoo-Pathy, N.T.; Dahlui, M.; See, M.H.; Yip, C.H.; Taib, N.A.; Bhoo-Pathy, N. Breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomy in young women with breast cancer in Asian settings. BJS Open 2019, 3, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Xie, Y.; Fan, Z.; Ouyang, T. Comparisons of breast conserving therapy versus mastectomy in young and old women with early-stage breast cancer: Long-term results using propensity score adjustment method. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 183, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Li, L.; Xiu, B.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Chi, Y.; Xue, J.; Wu, J. The Prognoses of Young Women With Breast Cancer (≤35 years) With Different Surgical Options: A Propensity Score Matching Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 795023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Wei, W.; Liu, P.; Xiao, X.; Xie, X.; Guan, X.; Yang, M.; Tang, J. Breast-conserving therapy: A viable option for young women with early breast cancer--evidence from a prospective study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 2188–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard-Fortier, A.; Baxter, N.N.; Sutradhar, R.; Fernandes, K.; Camacho, X.; Graham, P.; Quan, M.L. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in young women with breast cancer: A population-based analysis of predictive factors and clinical impact. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, e562–e568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettwyler, S.A.; Thull, D.L.; McAuliffe, P.F.; Steiman, J.G.; Johnson, R.R.; Diego, E.J.; Mai, P.L. Timely cancer genetic counseling and testing for young women with breast cancer: Impact on surgical decision-making for contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 194, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, C.A.; Bao, J.; Gangi, A.; Amersi, F.; Zhang, X.; Giuliano, A.E.; Chung, A.P. Bilateral Mastectomy as Overtreatment for Breast Cancer in Women Age Forty Years and Younger with Unilateral Operable Invasive Breast Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 2168–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, C.; Liederbach, E.; Wang, C.; Lapin, B.; Winchester, D.J.; Yao, K. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy provides no survival benefit in young women with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014, 21, 3231–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, S.M.; Sepucha, K.; Ruddy, K.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Gelber, S.; Meyer, M.E.; Schapira, L.; Come, S.E.; Borges, V.F.; Golshan, M.; et al. Local Therapy Decision-Making and Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy in Young Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 3809–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terkelsen, T.; Rønning, H.; Skytte, A.B. Impact of genetic counseling on the uptake of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among younger women with breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeichner, S.B.; Zeichner, S.B.; Ruiz, A.L.; Markward, N.J.; Rodriguez, E. Improved long-term survival with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among young women. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, A.B.; Moo, T.A.; Stempel, M.; Zabor, E.C.; Khan, A.J.; Morrow, M. Axillary management for young women with breast cancer varies between patients electing breast-conservation therapy or mastectomy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 180, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, E.; Cordeiro, E.; Roberts, A. Young Women with Breast Cancer: Chemotherapy or Surgery First? An Evaluation of Time to Treatment for Invasive Breast Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 2254–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhili, S.; Ouabdelmoumen, A.; Sbai, A.; Kebdani, T.; Benjaafar, N.; Mezouar, L. Radical Mastectomy Increases Psychological Distress in Young Breast Cancer Patients: Results of A Cross-sectional Study. Clin. Breast. Cancer 2019, 19, e160–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olasehinde, O.; Arije, O.; Wuraola, F.O.; Samson, M.; Olajide, O.; Alabi, T.; Arowolo, O.; Boutin-Foster, C.; Alatise, O.I.; Kingham, T.P. Life Without a Breast: Exploring the Experiences of Young Nigerian Women After Mastectomy for Breast Cancer. J. Glob. Oncol. 2019, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.M.; Dominici, L.S.; Gelber, S.; Poorvu, P.D.; Ruddy, K.J.; Wong, J.S.; Tamimi, R.M.; Schapira, L.; Come, S.; Peppercorn, J.M.; et al. Association of Breast Cancer Surgery With Quality of Life and Psychosocial Well-being in Young Breast Cancer Survivors. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.M.; Greaney, M.L.; Patenaude, A.F.; Partridge, A.H. Factors Affecting Surgical Decisions in Newly Diagnosed Young Women with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2019, 8, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.M.; Greaney, M.L.; Patenaude, A.F.; Sepucha, K.R.; Meyer, M.E.; Partridge, A.H. “I don’ t want to take chances": A qualitative exploration of surgical decision making in young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 1524–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanakidou, I.; Zyga, S.; Alikari, V.; Tsironi, M.; Stathoulis, J.; Theofilou, P. Mental health, loneliness, and illness perception outcomes in quality of life among young breast cancer patients after mastectomy: The role of breast reconstruction. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozawa, K.; Ichimura, M.; Oshima, A.; Tokunaga, E.; Masuda, N.; Kitano, A.; Fukuuchi, A.; Shinji, O. The present state and perception of young women with breast cancer towards breast reconstructive surgery. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 20, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bantema-Joppe, E.J.; de Bock, G.H.; Woltman-van Iersel, M.; Busz, D.M.; Ranchor, A.V.; Langendijk, J.A.; Maduro, J.H.; van den Heuvel, E.R. The impact of age on changes in quality of life among breast cancer survivors treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recio-Saucedo, A.; Gerty, S.; Foster, C.; Eccles, D.; Cutress, R.I. Information requirements of young women with breast cancer treated with mastectomy or breast conserving surgery: A systematic review. Breast 2016, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seror, V.; Cortaredona, S.; Bouhnik, A.D.; Meresse, M.; Cluze, C.; Viens, P.; Rey, D.; Peretti-Watel, P. Young breast cancer patients’ involvement in treatment decisions: The major role played by decision-making about surgery. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 2546–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Wang, W.J.; Warnack, E.; Joseph, K.A.; Schnabel, F.; Axelrod, D.; Dhage, S. Surgical treatment of young women with breast cancer: Public vs private hospitals. Breast J. 2019, 25, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, M.C.; Yen, R.W.; Elwyn, G.; O’ Malley, A.J.; Saunders, C.H.; Schubbe, D.; Forcino, R.; Durand, M.A. Women Who Are Young, Non-White, and with Lower Socioeconomic Status Report Higher Financial Toxicity up to 1 Year After Breast Cancer Surgery: A Mixed-Effects Regression Analysis. Oncologist 2021, 26, e142–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, F.; Gao, H.; Zhuang, X.; Li, W.; Pan, W.; Shen, B.; Zhang, T.; et al. Effects of Surgery on Prognosis of Young Women With Operable Breast Cancer in Different Marital Statuses: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 666316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.R.; Chae, E.Y.; Cha, J.H.; Shin, H.J.; Choi, W.J.; Kim, H.H. Preoperative Breast MRI in Women 35 Years of Age and Younger with Breast Cancer: Benefits in Surgical Outcomes by Using Propensity Score Analysis. Radiology 2021, 300, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, L.; Liederbach, E.; Velasco, J.; Pesce, C.; Wang, C.H.; Yao, K. Variation in Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy Rates According to Racial Groups in Young Women with Breast Cancer, 1998 to 2011: A Report from the National Cancer Data Base. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015, 221, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, S.M.; Tracy, M.S.; Meyer, M.E.; Sepucha, K.; Gelber, S.; Hirshfield-Bartek, J.; Troyan, S.; Morrow, M.; Schapira, L.; Come, S.E.; et al. Perceptions, knowledge, and satisfaction with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among young women with breast cancer: A cross-sectional survey. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 159, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.C.; Ziogas, A.; Anton-Culver, H. Delay in surgical treatment and survival after breast cancer diagnosis in young women by race/ethnicity. JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Collins, R.; Darby, S.; Davies, C.; Elphinstone, P.; Evans, V.; Godwin, J.; Gray, R.; Hicks, C.; James, S.; et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005, 366, 2087–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, T.M.; Habermann, E.B.; Grund, E.H.; Morris, T.J.; Virnig, B.A. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: A trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 5203–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.E.; Ballman, K.V.; McCall, L.; Beitsch, P.D.; Brennan, M.B.; Kelemen, P.R.; Ollila, D.W.; Hansen, N.M.; Whitworth, P.W.; Blumencranz, P.W.; et al. Effect of Axillary Dissection vs No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, M.; van Tienhoven, G.; Straver, M.E.; Meijnen, P.; van de Velde, C.J.; Mansel, R.E.; Cataliotti, L.; Westenberg, A.H.; Klinkenbijl, J.H.; Orzalesi, L.; et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sávolt, Á.; Péley, G.; Polgár, C.; Udvarhelyi, N.; Rubovszky, G.; Kovács, E.; Győrffy, B.; Kásler, M.; Mátrai, Z. Eight-year follow up result of the OTOASOR trial: The Optimal Treatment Of the Axilla-Surgery Or Radiotherapy after positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer: A randomized, single centre, phase III, non-inferiority trial. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, A.P.; Hoskin, T.L.; Day, C.N.; Sanders, S.B.; Boughey, J.C. Contemporary Axillary Management in cT1-2N0 Breast Cancer with One or Two Positive Sentinel Lymph Nodes: Factors Associated with Completion Axillary Lymph Node Dissection Within the National Cancer Database. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4740–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, L.; Brown, S.; Harvey, I.; Olivier, C.; Drew, P.; Napp, V.; Hanby, A.; Brown, J. Comparative effectiveness of MRI in breast cancer (COMICE) trial: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 375, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Year | Journal | Outcome Evaluated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilewskie M, King TA [24] | 2014 | J Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Sun ZH, Chen C et al. [25] | 2021 | Medicine | Surgery-Breast |

| Ye JC, Yan W et al. [26] | 2015 | Clin Breast Cancer | Surgery-Breast |

| Yu P, Tang H, et al. [27] | 2020 | Cancer Control | Surgery-Breast |

| Yu TJ, Liu YY et al. [28] | 2018 | Eur J Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Byun DJ, Wu SP, et al. [29] | 2021 | Ann Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Lazow SP, Riba L, et al. [30] | 2019 | Breast J | Surgery-Breast |

| Orozco JI, Keller JK et al. [31] | 2022 | Ann Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Pesce CE, Liederbach E et al. [32] | 2014 | J Am Coll Surg | Surgery-Breast |

| Rutter CE, Park HS et al. [33] | 2014 | Ann Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Kim HJ, Dominici L et al. [34] | 2022 | Ann Surg | Surgery-Breast |

| He XM, Zou DH [35] | 2017 | Sci Rep | Surgery-Breast |

| Chien JC, Liu WS et al. [36] | 2022 | Breast | Surgery-Breast |

| Vila J, Gandini S et al. [37] | 2015 | Breast | Surgery-Breast |

| Cronin PA, Olcese C et al. [38] | 2015 | Ann Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Bao S, He G [39] | 2022 | Breast J | Surgery-Breast |

| Cao JQ, Truong PT et al. [40] | 2014 | Int J Radiat Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Chen LJ, Chang YJ et al. [41] | 2021 | BJS Open | Surgery-Breast |

| Frandsen J, Ly D et al. [42] | 2015 | Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys | Surgery-Breast |

| Jeon YW, Choi JE et al. [43] | 2013 | Breast Cancer Res Treat | Surgery-Breast |

| Maishman T, Cutress RI et al. [44] | 2017 | Ann Surg | Surgery-Breast |

| Quan ML, Paszat LF et al. [45] | 2017 | J Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Sinnaduri S, Kwong A, et al. [46] | 2019 | BJS Open | Surgery-Breast |

| Wang L, He Y et al. [47] | 2020 | Breast Cancer Res Treat | Surgery-Breast |

| Li P, Li L et al. [48] | 2022 | Front Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Xie Z, Wang X et al. [49] | 2014 | Ann Surg Oncol | Surgery-Breast |

| Bouchard-Fortier A, Baxter NN et al. [50] | 2018 | Curr Oncol | Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy |

| Dettwyler SA, Thull DL et al. [51] | 2022 | Breast Cancer Res Treat | Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy |

| Donovan CA, Bao J et al. [52] | 2017 | Ann Surg Oncol | Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy |

| Pesce CE, Liederbach E et al. [53] | 2014 | Ann Surg Oncol | Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy |

| Rosenberg SM, Sepucha K et al. [54] | 2015 | Ann Surg Oncol | Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy |

| Terkelsen T, Ronning H, et al. [55] | 2020 | Acta Oncol | Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy |

| Zeichner SB, Ruiz AL et al. [56] | 2014 | Asian Pac J Cancer Prev | Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy |

| Tadros AB, Moo TA et al. [57] | 2020 | Breast Cancer Res Treat | Surgery-Axilla |

| Guay E, Cordeiro E et al. [58] | 2022 | Ann Surg Oncol | Surgical Timing |

| Berhili S, Ouabdelmoumen A et al. [59] | 2019 | Clin Breast Cancer | Psychological |

| Olasehinde O, Arije O et al. [60] | 2019 | J Glob Oncol | Psychological |

| Rosenberg SM, Dominici LS et al. [61] | 2020 | JAMA Surg | Psychological |

| Rosenberg SM, Greaney ML et al. [62] | 2019 | J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol | Psychological |

| Rosenberg SM, Greaney ML et al. [63] | 2018 | Psychooncology | Psychological |

| Fanakidou, I, Zyga S, et al. [64] | 2018 | Qual Life Res | Psychological |

| Nozawa K, Ichimura M et al. [65] | 2015 | Int J Clin Oncol | Psychological |

| Bantema-Joppe EJ, de Bock GH et al. [66] | 2015 | Br J Cancer | Psychological |

| Recio-Saucedo A, Gerty S et al. [67] | 2016 | Breast | Psychological |

| Seror V, Cortaredona S, et al. [68] | 2013 | Psychooncology | Psychological |

| Patel A, Wang WJ et al. [69] | 2019 | Breast J | Disparity |

| Politi MC, Yen RW et al. [70] | 2021 | Oncologist | Disparity |

| Zhang J, Yang C et al. [71] | 2021 | Front Oncol | Disparity |

| Park AR, Chae EY et al. [72] | 2021 | Radiology | MRI Evaluation on Breast Surgery |

| Grimmer L, Liederbach E et al. [73] | 2015 | J Am Coll Surg | Multiple-Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy and Disparity |

| Rosenberg SM, Tracy MS et al. [74] | 2013 | Ann Intern Med | Multiple-Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy and Psychological |

| Smith EC, Ziogas A et al. [75] | 2013 | JAMA Surg | Multiple-Surgical Timing and Disparity |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murphy, B.L.; Pereslucha, A.; Boughey, J.C. Current Considerations in Surgical Treatment for Adolescents and Young Women with Breast Cancer. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122542

Murphy BL, Pereslucha A, Boughey JC. Current Considerations in Surgical Treatment for Adolescents and Young Women with Breast Cancer. Healthcare. 2022; 10(12):2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122542

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurphy, Brittany L., Alicia Pereslucha, and Judy C. Boughey. 2022. "Current Considerations in Surgical Treatment for Adolescents and Young Women with Breast Cancer" Healthcare 10, no. 12: 2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122542

APA StyleMurphy, B. L., Pereslucha, A., & Boughey, J. C. (2022). Current Considerations in Surgical Treatment for Adolescents and Young Women with Breast Cancer. Healthcare, 10(12), 2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122542