Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Recent Advances in Understanding and Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

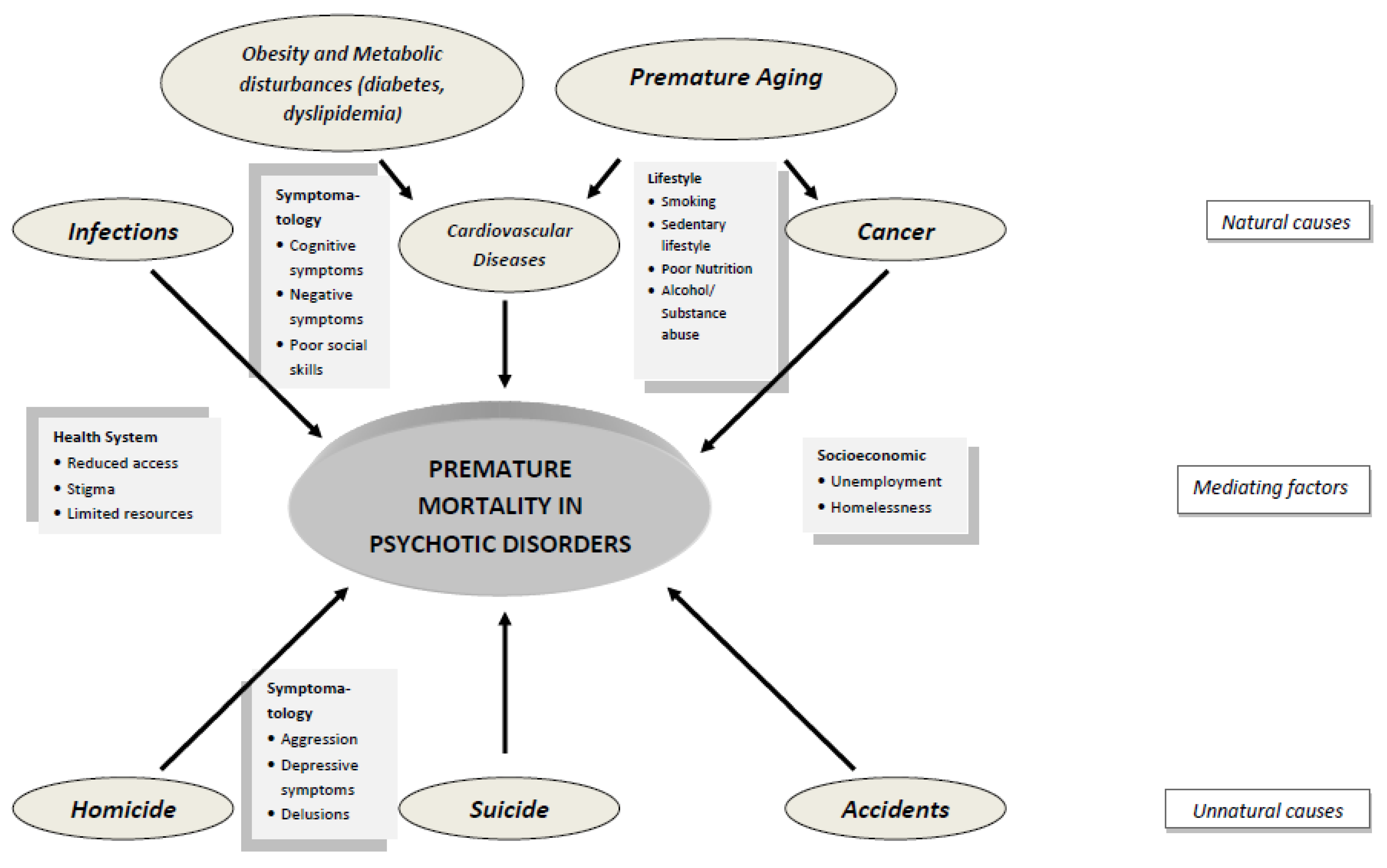

2. Mortality Rates in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders

3. Causes of Mortality

3.1. Unnatural Causes of Death

3.1.1. Accidents

3.1.2. Suicide

3.1.3. Homicide

3.2. Natural Causes

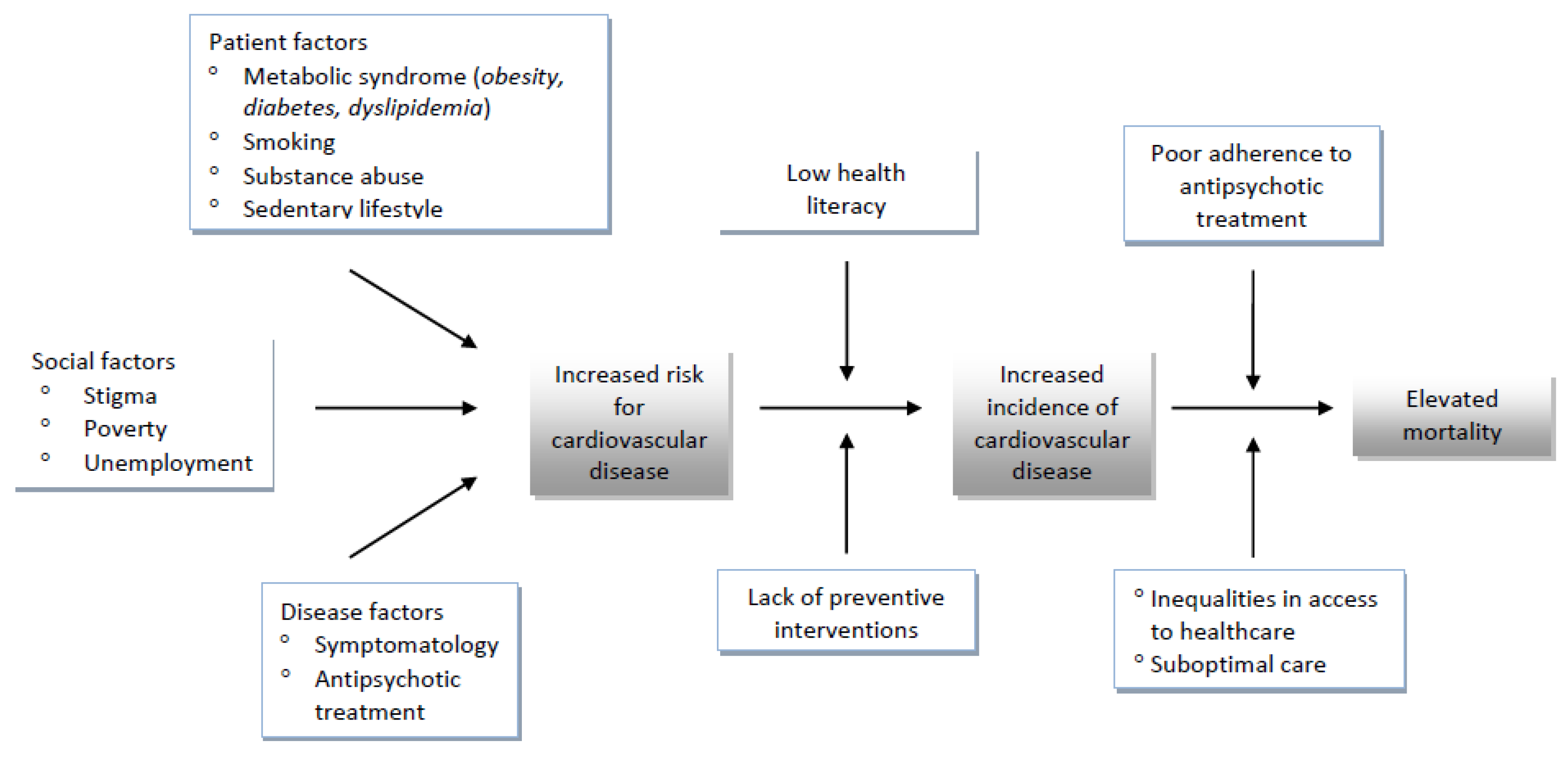

3.2.1. Cardiovascular Disease

3.2.2. Respiratory Tract Diseases

3.2.3. Infections

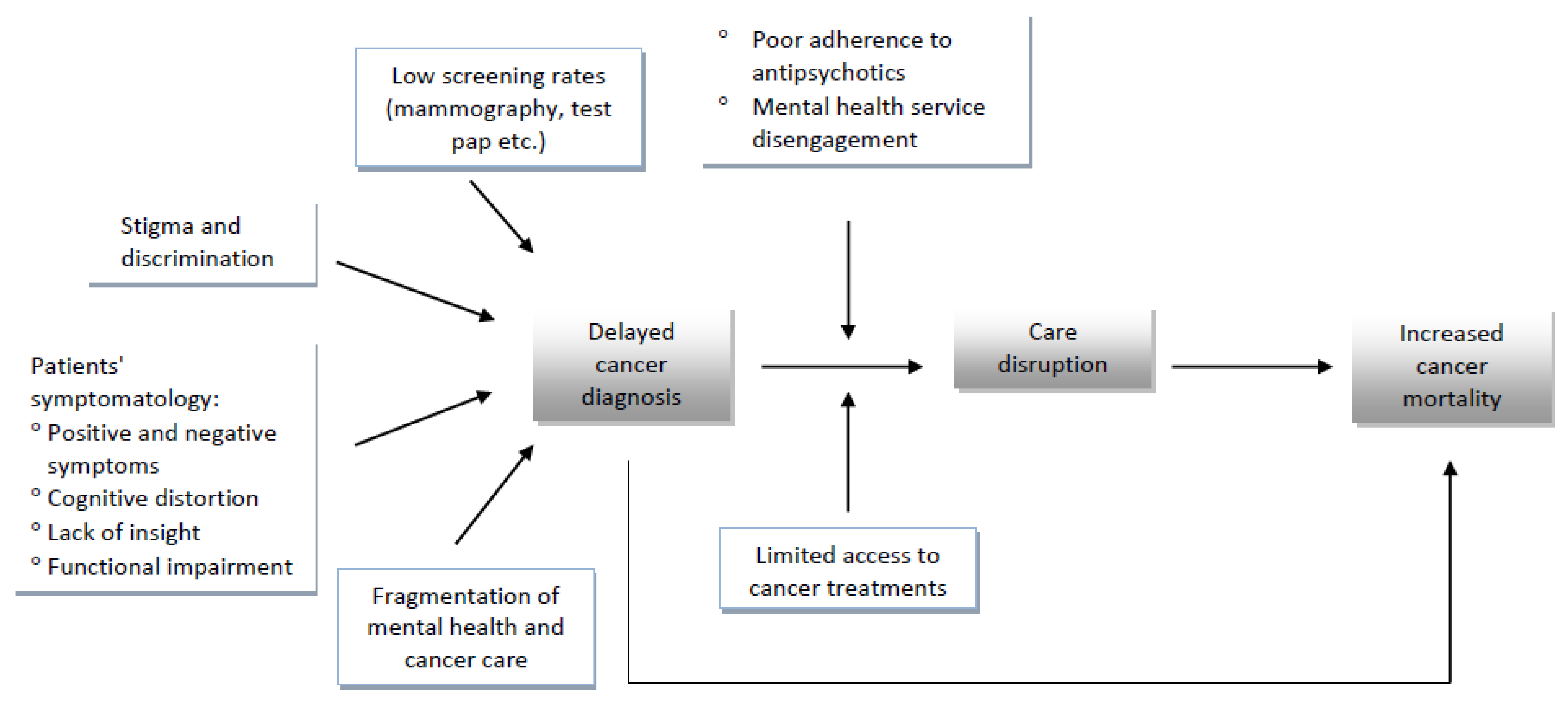

3.2.4. Cancer

4. Contributing Factors to Increased Mortality

4.1. Smoking

4.2. Alcohol/Substance Abuse

4.3. Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

4.4. Diabetes Mellitus

4.5. Accelerating Aging in Psychotic Disorders

4.6. Sedentary Lifestyle and Reduced Physical Activity

4.7. Antipsychotic Medication

5. Other Factors Associated with Elevated Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders

5.1. Access to Medical Care and Quality of Care

5.2. Stigma

6. Protective Factors

7. Discussion

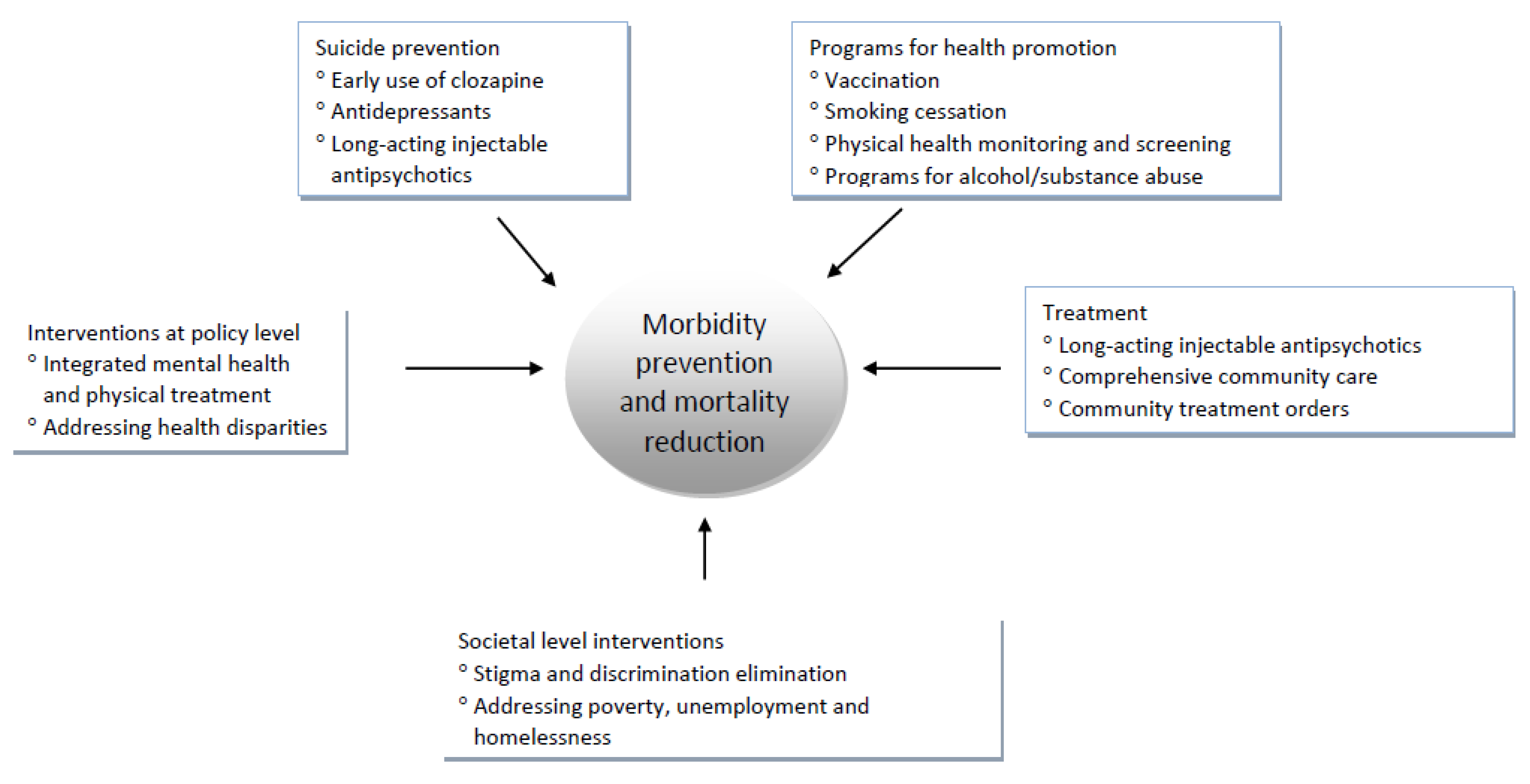

7.1. Interventions for the Reduction of Mortality in Schizophrenia

7.2. Suicide Prevention

7.3. Implications for Healthcare Policy and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, S.; Kim, M.; Mitchell, C.; Inskip, H. Twenty five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 196, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesney, E.; Goodwin, G.; Fazel, S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, E.R.; McGee, R.E.; Druss, B.G. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858.

- Volavka, J.; Vevera, J. Very long- term outcome of schizophrenia. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 72, e13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Gogou, A.; Samakouri, M. Very long-term outcome of psychotic disorders. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, S.; Johnstone, M.; McKenna, P.J. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2022, 399, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, J.; MacCabe, J.H. Antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: A review. Br. Med. Bull. 2015, 114, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreyenbuhl, J.; Nossel, I.R.; Dixon, L.B. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: A review of the literature. Schizophr. Bull. 2009, 35, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, H.; Kirino, S.; Remington, G.; Misawa, F.; Takeuchi, H. Adherence to Oral Antipsychotics Measured by Electronic Adherence Monitoring in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Sohn, J.H. Adherence to Antipsychotic Drugs by Medication Possession Ratio for Schizophrenia and Similar Psychotic Disorders in the Republic of Korea: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2022, 20, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allebeck, P. Schizophrenia: A life-shortening disease. Schizophr. Bull. 1989, 15, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Chant, D.; McGrath, J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Liu, J.; Tu, X.; Palmer, B.; Eyler, L.; Jeste, D. A Widening Longevity Gap between People with Schizophrenia and General Population: A Literature Review and Call for Action. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 196, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, S.; Thornicroft, G. Reducing the Mortality Gap in People With Severe Mental Disorders: The Role of Lifestyle Psychosocial Interventions. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.; Hancock, K.J.; Kisely, S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: Retrospective analysis of population based registers. BMJ 2013, 346, f2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Correll, C.U.; Bobes, J.; Cetkovich-Bakmas, M.; Cohen, D.; Asai, I.; Detraux, J.; Gautam, S.; Möller, H.-J.; Ndetei, D.M.; et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjorthøj, C.; Stürup, A.E.; McGrath, J.; Nordentoft, M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jang, S.Y.; Chun, S.Y.; Lee, T.H.; Han, K.T.; Park, E.C. Mortality in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses: Data from the South Korea National Health Insurance Cohort, 2002–2013. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininghaus, U.; Dutta, R.; Dazzan, P.; Doody, G.A.; Fearon, P.; Lappin, J.; Heslin, M.; Onyejiaka, A.; Donoghue, K.; Lomas, B.; et al. Mortality in schizophrenia and other psychoses: A 10-year follow-up of the ӔSOP first-episode cohort. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Santomauro, D.; Ferrari, A.J.; Charlson, F. Excess mortality in severe mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 149, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Daumit, G.; Dua, T.; Aquila, R.; Charlson, F.; Cuijpers, P.; Druss, B.; Dudek, K.; Freeman, M.; Fujii, C.; et al. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: A multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crump, C.; Sundquist, K.; Winkleby, M.; Sundquist, J. Mental disorders and risk of accidental death. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 203, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemose, L.A.A.; Laursen, T.M.; Larsen, J.T.; Toender, A. Accidental deaths among persons with schizophrenia: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 199, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, A.P.S.; Dippenaar, I.N.; Johnson, S.C.; Weaver, N.D.; de Assis Acurcio, F.; Malta, D.C.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Júnior, A.A.G.; Wool, E.E.; Naghavi, M.; et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among people with severe mental illness in Brazil’s public health system, 2000–2015: A retrospective study. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hor, K.; Taylor, M. Suicide and schizophrenia: A systematic review of rates and risk factors. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 24, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, L.; Kahn, R. Suicide in Schizophrenia: An Educational Overview. Medicina 2019, 55, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, D.; Benabarre, A.; Crespo, J.M.; Goikolea, J.M.; González-Pinto, A.M.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, L.; Montes, J.M.; Vieta, E. Risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia: Systematic review and clinical recommendations. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014, 130, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, A.; Shah, B.; Shrivastava, A. Suicide and Schizophrenia: An Interplay of Factors. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latalova, K.; Kamaradova, D.; Prasko, J. Violent victimization of adult patients with severe mental illness: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1925–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Sundquist, K.; Winkleby, M.; Sundquist, J. Mental disorders and vulnerability to homicidal death: Swedish nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2013, 346, f557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sariaslan, A.; Arseneault, L.; Larsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P.; Fazel, S. Risk of Subjection to Violence and Perpetration of Violence in Persons With Psychiatric Disorders in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Blanchard, T.; Fowler, D.; Li, L. Causes of Sudden Unexpected Death in Schizophrenia Patients: A Forensic Autopsy Population Study. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2019, 40, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Vancampfort, D. The intriguing relationship between coronary heart disease and mental disorders. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatov, E.; Rosella, L.; Chiu, M.; Kurdyak, P. Trends in standardized mortality among individuals with schizophrenia, 1993–2012: A population-based, repeated cross-sectional study. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2017, 189, E1177–E1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, J.; Eriksson, S.V.; Gissler, M.; Hällgren, J.; Prieto, M.L.; Bobo, W.V.; Frye, M.A.; Erlinge, D.; Alfredsson, L.; Ösby, U. Increased cardiovascular mortality in people with schizophrenia: A 24-year national register study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Bortolato, B.; Rosson, S.; Santonastaso, P.; Thapa-Chhetri, N.; Fornaro, M.; Gallicchio, D.; Collantoni, E.; et al. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannoodee, H.; Al Khalili, M.; Theik, N.; Raji, O.E.; Shenwai, P.; Shah, R.; Kalluri, S.R.; Bhutta, T.H.; Khan, S. The Outcomes of Acute Coronary Syndrome in Patients Suffering From Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e16998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, M.; De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Di Palo, K.; Munir, H.; Music, S.; Piña, I.; Ringen, P.A. Severe Mental Illness and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M.; Gerhard, T.; Huang, C.; Crystal, S.; Stroup, T.S. Premature Mortality Among Adults With Schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lluch, E.; Miller, B.J. Rates of hepatitis B and C in patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2019, 61, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toubasi, A.; AbuAnzeh, R.; Abu Tawileh, H.; Aldebei, R.; Alryalat, S.A. A meta-analysis: The mortality and severity of COVID-19 among patients with mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 299, 113856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzur Bitan, D.; Krieger, I.; Kridin, K.; Komantscher, D.; Scheinman, Y.; Weinstein, O.; Cohen, A.D.; Cicurel, A.A.; Feingold, D. COVID-19 Prevalence and Mortality Among Schizophrenia Patients: A Large-Scale Retrospective Cohort Study. Schizophr. Bull. 2021, 47, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hert, M.; Mazereel, V.; Detraux, J.; Van Assche, K. Prioritizing COVID-19 vaccination for people with severe mental illness. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 54–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazereel, V.; Vanbrabant, T.; Desplenter, F.; Detraux, J.; De Picker, L.; Thys, E.; Popelier, K.; De Hert, M. COVID-19 vaccination rates in a cohort study of patients with mental illness in residential and community care. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 805528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Drakatos, I.; Gioti, P.; Garbi, A. Vaccination rates against COVID-19 in patients with severe mental illness attending community mental health services in rural Greece. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry, 2022; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musuuza, J.; Sherman, M.; Knudsen, K.; Sweeney, H.A.; Tyler, C.; Koroukian, S. Analyzing Excess Mortality From Cancer Among Individuals With Mental Illness. Cancer 2013, 119, 2469–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wu, J.; Long, Y.; Tao, J.; Xu, J.; Yuan, X.; Yu, N.; Wu, R.; Zhang, Y. Mortality of site-specific cancer in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Zheng, H.; Sun, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Bi, X. The incidence rate of cancer in patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 195, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, C.; Triplett, P.T. Association of Schizophrenia With the Risk of Breast Cancer Incidence: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootten, J.C.; Wiener, J.C.; Blanchette, P.S.; Anderson, K.K. Cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis among people with psychotic disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 80, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launders, N.; Scolamiero, L.; Osborn, D.P.J.; Hayes, J.F. Cancer rates and mortality in people with severe mental illness: Further evidence of lack of parity. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 246, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, K.E.; Park, E.R.; Shin, J.A.; Fields, L.E.; Jacobs, J.M.; Greer, J.A.; Taylor, J.B.; Taghian, A.G.; Freudenreich, O.; Ryan, D.P.; et al. Predictors of Disruptions in Breast Cancer Care for Individuals with Schizophrenia. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.C.N.; Ng, D.W.Y.; Chu, R.Y.K.; Chan, E.W.W.; Huang, L.; Lum, D.H.; Chan, E.W.Y.; Smith, D.J.; Wong, I.C.K.; Lai, F.T.T. Association of antipsychotic use with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies with over 2 million individuals. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, H.; Solmi, M.; Lähteenvuo, M.; Tanskanen, A.; Correll, C.U.; Tiihonen, J. Antipsychotic use and risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia: A nationwide nested case-control study in Finland. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagud, M.; Mihaljevic Peles, A.; Pivac, N. Smoking in schizophrenia: Recent findings about an old problem. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, H.; MacCabe, J. The relationship between nicotine and psychosis. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogos, A.; Skokou, M.; Ferentinou, E.; Gourzis, P. Nicotine consumption during the prodromal phase of schizophrenia—A review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 2943–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhar JY, Dwiel LL, Henricks AM, Doucette WT, Green AI: The link between schizophrenia and substance use disorder: A unifying hypothesis. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 194, 78–85. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Vancampfort, D.; Sweers, K.; van Winkel, R.; Yu, W.; De Hert, M. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome and Metabolic Abnormalities in Schizophrenia and Related Disorders—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Dai, Q.; Andriescue, E.C.; Wu, H.E.; Xiu, M.; Chen, D.; et al. Obesity in Chinese patients with chronic schizophrenia: Prevalence, clinical correlates and relationship with cognitive deficits. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 215, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challa, F.; Getahun, T.; Sileshi, M.; Geto, Z.; Kelkile, T.; Gurmessa, S.; Medhin, G.; Mesfin, M.; Alemayehu, M.; Shumet, T.; et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among patients with schizophrenia in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Xu, H.; Dai, Q.; Xiu, M.; Chen, D.; Wang, L.; et al. Prevalence of obesity and clinical and metabolic correlates in first-episode schizophrenia relative to healthy controls. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.H.; Chien, I.C.; Lin, C.H.; Chou, Y.J.; Chou, P. Incidence of Diabetes in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Population-based Study. Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamakou, V.; Thanopoulou, A.; Gonidakis, F.; Tentolouris, N.; Kontaxakis, V. Schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Psychiatriki 2018, 29, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuki, Y.; Sakamoto, S.; Okahisa, Y.; Yada, Y.; Hashimoto, N.; Takaki, M.; Yamada, N. Mechanisms Underlying the Comorbidity of Schizophrenia and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 24, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D.; Maglione, J. Treating Older Adults With Schizophrenia: Challenges and Opportunities. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 966–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkowitz, O. Accelerated biological aging in serious mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Schuch, F.; Rosenbaum, S.; Mugisha, J.; Hallgren, M.; Probst, M.; Ward, P.B.; Gaughran, F.; De Hert, M.; et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, B.; Koyanagi, A.; Schuch, F.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Gaughran, F.; Mugisha, J.; Vancampfort, D. Physical Activity Levels and Psychosis: A Mediation Analysis of Factors Influencing Physical Activity Target Achievement Among 204 186 People Across 46 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Schizophr. Bull. 2017, 43, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; van Winkel, R.; Yu, W.; Correll, C. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Atypical Antipsychotics: Sleep, Sedation, and Efficacy. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 6 (Suppl. S2), 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Eugene, A.R.; Eugene, B.; Masiak, M.; Masiak, J.S. Head-to-Head Comparison of Sedation and Somnolence Among 37 Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder, Major Depression, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Delirium, and Repurposed in COVID-19, Infectious Diseases, and Oncology From the FAERS, 2004–2020. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 621691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, M.; Mainz, J.; Egstrup, K.; Johnsen, S.P. Quality of Care and Outcomes of Heart Failure Among Patients With Schizophrenia in Denmark. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, J.; Juel, J.; Alzuhairi, K.S.; Friis, R.; Graff, C.; Kanters, J.K.; Jensen, S.E. Unrecognised myocardial infarction in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2015, 27, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorkenstam, E.; Ljung, R.; Burstrom, B.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Hallqvist, J.; Ringback Weitoft, G. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in psychiatric patients-a nationwide register-based study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, A.; Samakouri, M.; Kalamara, E.; Bochtsou, V.; Bikos, C.; Livaditis, M. Health service staff’s attitudes towards patients with mental illness. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2009, 44, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Machado, D.; Fonseca, J.B.; Palha, F.; Silva Moreira, P.; Sousa, N.; Cerqueira, J.J.; Morgado, P. Stigmatizing Attitudes Toward Patients With Psychiatric Disorders Among Medical Students and Professionals. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harangozo, J.; Reneses, B.; Brohan, E.; Sebes, J.; Csukly, G.; López-Ibor, J.J.; Sartorius, N.; Rose, D.; Thornicroft, G. Stigma and discrimination against people with schizophrenia related to medical services. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 60, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correll, C.U.; Rubio, J.M.; Kane, J.M. What is the risk-benefit ratio of long-term antipsychotic treatment in people with schizophrenia? World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, J.; Lönnqvist, J.; Wahlbeck, K.; Klaukka, T.; Niskanen, L.; Tanskanen, A.; Haukka, J. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: A population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet 2009, 374, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Mehtälä, J.; Vattulainen, P.; Correll, C.U.; Tiihonen, J. 20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.-Y.; Yeh, L.-L.; Pan, Y.-J. Exposure to psychotropic medications and mortality in schizophrenia: A 5-year national cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, D.; Bolton, J.M.; Leong, C.; Kuo, I.; Alessi-Severini, S. Second- Generation Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics and the Risk of Treatment Failure in a Population- Based Cohort. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 879224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.Y.; Fang, S.C.; Shao, Y.J. Comparison of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics With Oral Antipsychotics and Suicide and All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Schizophrenia. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e218810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Preston, N.; Xiao, J.; Lawrence, D.; Louise, S.; Crowe, E. Reducing all-cause mortality among patients with psychiatric disorders: A population-based study. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2013, 185, E50–E56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latoo, J.; Mistry, M.; Dunne, F. Physical morbidity and mortality in people with mental illness. Br. J. Med. Pract. 2013, 6, a621. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas, A.; Chesney, E.; Patel, R. Improving life expectancy in people with serious mental illness: Should we place more emphasis on primary prevention? Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 211, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Solmi, M.; Croatto, G.; Schneider, L.K.; Rohani-Montez, S.C.; Fairley, L.; Smith, N.; Bitter, I.; Gorwood, P.; Taipale, H.; et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, E.E.; Baller, J.; Azrin, S.T.; Juliano-Bult, D.; Daumit, G.L. Interventions to Address Medical Conditions and Health-Risk Behaviors Among Persons With Serious Mental Illness: A Comprehensive Review. Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 42, 96–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ride, J.; Kasteridis, P.; Gutacker, N.; Kronenberg, C.; Doran, T.; Mason, A.; Rice, N.; Gravelle, H.; Goddard, M.; Kendrick, T.; et al. Do care plans and annual reviews of physical health influence unplanned hospital utilization for people with serious mental illness? Analysis of linked longitudinal primary and secondary healthcare records in England. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Liu, Z.H.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Q.E.; Rao, W.W.; Cheung, T.; Hall, B.J.; Xiang, Y.T. Worldwide prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide plan among people with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiological surveys. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, I.; Rogante, E.; Sarubbi, S.; Erbuto, D.; Lester, D.; Pompili, M. The Importance of Suicide Risk Formulation in Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 779684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, P.; Busch, S.; Shih, Y.W.; McGregor, A.; Wang, S. Changes in community mental health services availability and suicide mortality in the US: A retrospective study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teferra, S.; Shibre, T.; Fekadu, A.; Medhin, G.; Wakwoya, A.; Alem, A.; Kullgren, G.; Jacobsson, L. Five-year mortality in a cohort of people with schizophrenia in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanujam, G.; Thara, R.; Sujit, J.; Sunitha, K. Methodology for Development of a Community Level Intervention Module for Physical Illness in Persons with Mental Illness (CLIPMI). Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 94S–98S. [Google Scholar]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Samakouri, M. Research on psychotic disorders in rural areas. Recent advances and ongoing challenges. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 1046–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.A.; Barksdale, C.L.; Beckel-Mitchener, A.C. A call to action to address rural mental health disparities. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 4, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Winkleby, M.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: A Swedish national cohort study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Fiedorowicz, J.; Poddighe, L.; Delogu, M.; Miola, A.; Høye, A.; Heiberg, I.H.; Stubbs, B.; Smith, L.; Larsson, H.; et al. Disparities in Screening and Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases in Patients With Mental Disorders Across the World: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 47 Observational Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M.; Dalton, J.; Harden, M.; Street, A.; Parker, G.; Eastwood, A. Integrated Care to Address the Physical Health Needs of People with Severe Mental Illness: A Mapping Review of the Recent Evidence on Barriers, Facilitators and Evaluations. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; Riba, M. Cancer and severe mental illness: Bi-directional problems and potential solutions. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, G.; Chen, W.; Large, M.; Ramanuj, P.; Curtis, J.; McMillan, F.; Mulder, C.L.; Currow, D.; Burgess, P. Potentially preventable hospitalisations for physical health conditions in community mental health service users: A population-wide linkage study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Facorro, B.; Pelayo-Teran, J.M.; Mayoral-van Son, J. Current Data on and Clinical Insights into the Treatment of First Episode Nonaffective Psychosis: A Comprehensive Review. Neurol. Ther. 2016, 5, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, N.; O’Connor, K.; McGrath, D.; Vagge, L.; Mockler, D.; Jennings, R.; Darker, C.D. Early Intervention in Psychosis services: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the barriers and facilitators to implementation. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient-related factors | Unhealthy life style

Poor treatment adherence Low health literacy Sexual and other risky behaviors Stigma |

| Symptomatology | Cognitive dysfunction Negative symptoms Poor communicative and social skills |

| Treatment-related factors | Medication adverse effects

|

| Health services-related factors | Inadequate health care Negative attitudes of primary care personnel Limited knowledge of psychiatrists on general health issues Stigma Inadequate liaison of services Lack of resources |

| Other disease-related factors | Inter-relationship between schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus Premature aging Reduced pain perception |

| Socioeconomic factors | Unemployment Homelessness |

| At patient level |

|

| At service level |

|

| At policy level |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peritogiannis, V.; Ninou, A.; Samakouri, M. Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Recent Advances in Understanding and Management. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122366

Peritogiannis V, Ninou A, Samakouri M. Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Recent Advances in Understanding and Management. Healthcare. 2022; 10(12):2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122366

Chicago/Turabian StylePeritogiannis, Vaios, Angeliki Ninou, and Maria Samakouri. 2022. "Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Recent Advances in Understanding and Management" Healthcare 10, no. 12: 2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122366

APA StylePeritogiannis, V., Ninou, A., & Samakouri, M. (2022). Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Recent Advances in Understanding and Management. Healthcare, 10(12), 2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122366