A Prehospital Emergency Psychiatric Unit in an Ambulance Care Service from the Perspective of Prehospital Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Setting and Population

2.3. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

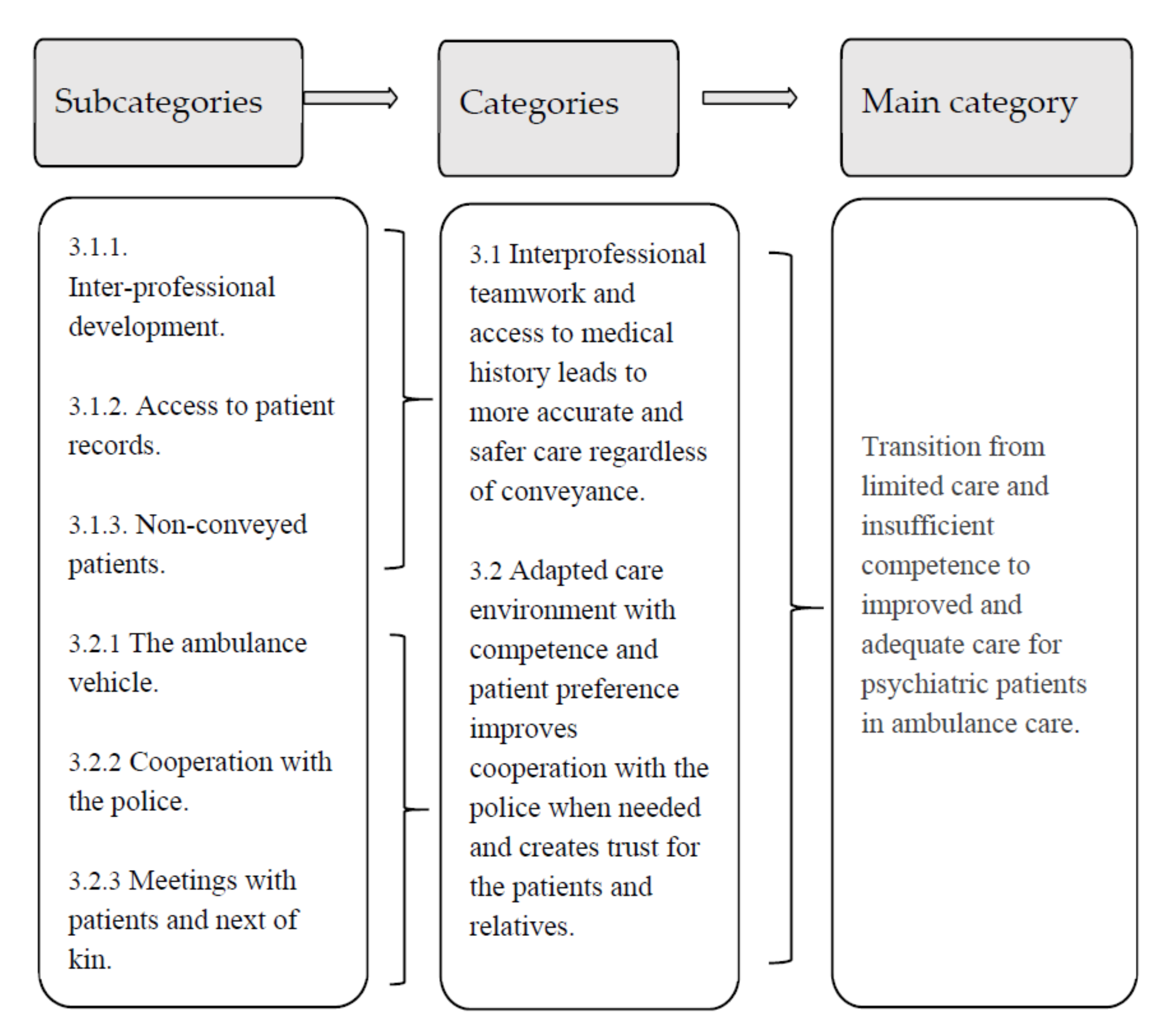

3. Results

3.1. Interprofessional Teamwork and Access to Medical History Leads to More Accurate and Safer Care Regardless of Conveyance

3.1.1. Inter-Professional Development

“My understanding of the psychiatry context and the psychiatry nurse’s challenges has increased… and their understanding of the somatic part of the ambulance care has improved. This together has led to better preliminary diagnoses and triage among the psychiatric patients. These patients get a double assessment that they do not get anywhere else… we together become more like one unit. And for me personally, it will take some time to become even better in the encounter with these patients, but I already feel a positive difference after 1 year of participation in this project”.(R4)

3.1.2. Access to Patient Records

“Access to medical record systems is fantastic for further treatment opportunities… to be able to be prepared before coming to the patient. Many of these patients do not have the strength or find it difficult to talk about certain things. Every time a regular ambulance unit handles a similar situation, you do not really know what the conversation should be about and sometimes you become unsure whether the patients tell the whole story of their illnesses”.(R1)

3.1.3. Non-Conveyed Patients

“It [expansion of drugs] means that we can treat more patients at home, that you do not always have to go to a psychiatric emergency… from the patient’s perspective it emerges that you [the patient] can get help at home, you can probably manage the situation until the next day and visit your own physician… you end up at the right level of care from the beginning. So, I think it has made a big difference”.(R5)

3.2. Adapted Care Environment Improves Cooperation with the Police and Creates Trust for Patients and Relatives

3.2.1. The Ambulance Vehicle

“Wow, is there no stretcher here?”… The patients seem to like this… it becomes more like a small chat room and the atmosphere does not become so “unhealthy”, though we can sit on chairs instead of the patient lying on a stretcher”.(R6)

3.2.2. Cooperation with the Police

“We have been treated very positively by the police force. They can now get a short report about the patient and they know that there is a specialist trained nurse in the ambulance who knows what it is about. It is not just someone [the psychiatric nurse] who has made a hasty decision that this patient should enter the hospital, no, there is, in fact, a formal theoretical knowledge behind this decision”.(R7)

3.2.3. Meetings with Patients and Next of Kin

“The patients who call the dispatch center many times, we know them in the ambulance service. We will never get rid of it, only the people change. We just have to learn to deal with them…I know and understand why they exist and how much they affect the rest of the system. Because these patients take a lot of attention”.(R2)

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 2021. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Kaster, T.S.; Vigod, S.N.; Gomes, T.; Wijeysundera, D.N.; Blumberger, D.M.; Sutradhar, R. A practical overview and decision tool for analyzing recurrent events in mental illness: A review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 137, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Durant, E.; Fahimi, J. Factors Associated with Ambulance Use Among Patients with Low-Acuity Conditions. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2012, 16, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford-Jones, P.C.; Chaufan, C. A Critical Analysis of Debates Around Mental Health Calls in the Prehospital Setting. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2017, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Booker, M.J.; Shaw, A.R.; Purdy, S. Why do patients with ‘primary care sensitive’ problems access ambulance services? A systematic mapping review of the literature. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, N.; Rapport, F.; Thomas, G.; John, A.; Snooks, H. Perceptions of paramedic and emergency care workers of those who self harm: A systematic review of the quantitative literature. Psychosomatics 2014, 77, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emond, K.; O’Meara, P.; Bish, M. Paramedic management of mental health related presentations: A scoping review. J. Ment. Health 2019, 28, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederman, J.; Lindström, V.; Elmqvist, C.; Löfvenmark, C.; Djärv, T. Non-conveyance in the ambulance service: A population-based cohort study in Stockholm, Sweden. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouveng, O.; Bengtsson, F.A.; Carlborg, A. First-year follow-up of the Psychiatric Emergency Response Team (PAM) in Stockholm County, Sweden: A descriptive study. Int. J. Ment. Health 2017, 46, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, C.; Herlitz, J.; Axelsson, C. Patient characteristics, triage utilisation, level of care, and outcomes in an unselected adult patient population seen by the emergency medical services: A prospective observational study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2020, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindström, V.; Sturesson, L.; Carlborg, A. Patients’ experiences of the caring encounter with the psychiatric emergency response team in the emergency medical service—A qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Todorova, L.; Johansson, A.; Ivarsson, B. Perceptions of ambulance nurses on their knowledge and competence when assessing psychiatric mental illness. Nurs. Open 2020, 8, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihlborg, J.; Edgren, G.; Johansson, A.; Sivberg, B. Reflective and collaborative skills enhances Ambulance nurses’ competence—A study based on qualitative analysis of professional experiences. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 32, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COREQ Checklist. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. The EQUATOR Network. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/19/6/349/1791966 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- La Pelle, N. Simplifying Qualitative Data Analysis Using General Purpose Software Tools. Field Methods 2004, 16, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, M.; Fagerberg, I. The encounter with the unknown: Nurses lived experiences of their responsibility for the care of the patient in the Swedish ambulance service. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, G.; Holmén, A.; Ziegert, K. Early prehospital assessment of non-urgent patients and outcomes at the appropriate level of care: A prospective exploratory study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 32, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, H.; Carlsson, J.; Karlsson, L.; Holmberg, M. Competency requirements for the assessment of patients with mental illness in somatic emergency care: A modified Delphi study from the nurses’ perspective. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 40, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W.; Boet, S.; Theriault, R.; Mallette, T.; Eva, K.W. Global Rating Scale for the Assessment of Paramedic Clinical Competence. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2013, 17, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.; Porter, M.; Williams, B. Towards a theoretical framework for situational awareness in paramedicine. Saf. Sci. 2020, 122, 104528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzäll, K.; Tällberg, J.; Lundin, T.; Suserud, B.-O. Threats and violence in the Swedish pre-hospital emergency care. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2011, 19, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.J.; Bassett, G.; Sinden, L.; Fothergill, R.T. Frequent callers to the ambulance service: Patient profiling and impact of case management on patient utilisation of the ambulance service. Emerg. Med. J. 2015, 32, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jansson, J.; Eklund, A.J.; Larsson, M.; Nilsson, J. Prehospital care nurses’ self reported competence: A cross-sectional study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 52, 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton-Locke, C.; Johnson, S.; Harju-Seppänen, J.; Lyons, N.; Rains, L.S.; Stuart, R.; Campbell, A.; Clark, J.; Clifford, A.; Courtney, L.; et al. Emerging models and trends in mental health crisis care in England: A national investigation of crisis care systems. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Todorova, L.; Johansson, A.; Ivarsson, B. A Prehospital Emergency Psychiatric Unit in an Ambulance Care Service from the Perspective of Prehospital Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010050

Todorova L, Johansson A, Ivarsson B. A Prehospital Emergency Psychiatric Unit in an Ambulance Care Service from the Perspective of Prehospital Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2022; 10(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleTodorova, Lizbet, Anders Johansson, and Bodil Ivarsson. 2022. "A Prehospital Emergency Psychiatric Unit in an Ambulance Care Service from the Perspective of Prehospital Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 10, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010050

APA StyleTodorova, L., Johansson, A., & Ivarsson, B. (2022). A Prehospital Emergency Psychiatric Unit in an Ambulance Care Service from the Perspective of Prehospital Emergency Nurses: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 10(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010050