Digital Tools in Behavior Change Support Education in Health and Other Students: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

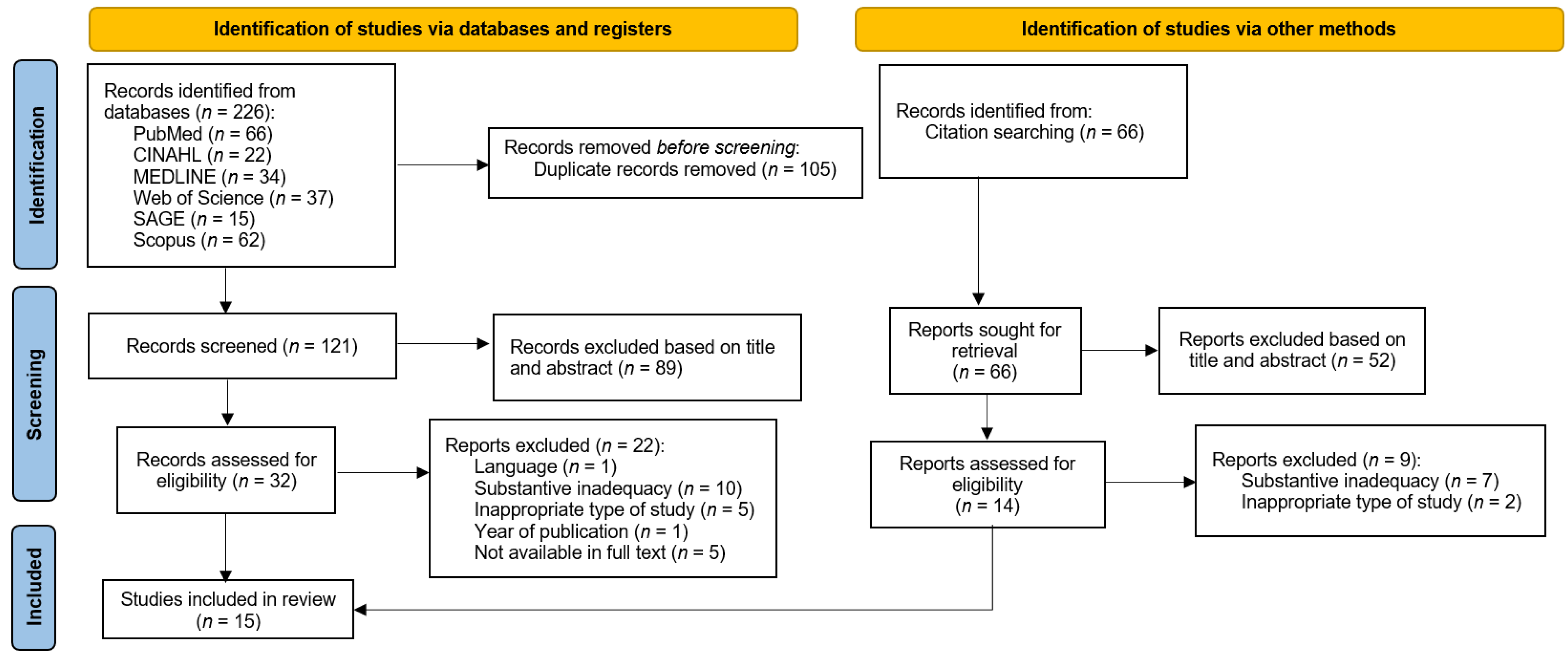

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Results of Literature Review

3.2. Assessment Instruments to Evaluate Research Outcomes

3.3. Assessment of the Digital Teaching Tools Outcomes

| Main Themes | Subthemes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Positive outcomes of using digital teaching tools | Knowledge | -knowledge retention [39,49] -increase in knowledge [39] -active learning [38] -developing/improving skills [36,40] -critical thinking [38] -significantly higher counseling [39] |

| Confidence | -builds confidence [38] -felt more confident [48,49] -skills increased [41] -diabetes education skills assessed [41] -trust [45] | |

| Practical experience | -more prepared for interprofessional education [37] -improve the professional practice [35] -effect on their clinical/professional practice [44] -expressed satisfaction with experiencing such a practice [36] | |

| Collaboration | -increase their professional network [35] -think more positively about other professionals [37] | |

| Barriers to the use of digital teaching tools | Restrictions | -using only one patient simulator [37] -time in students’ schedules [43] -financial resources [43] -space [43] -lagging feedback [46] -technology issues [46] |

| Suggestions for improvement | -faculty time to develop activities [46] |

4. Discussion

4.1. Assessment Tools

4.2. Implications for Practice and Policy

4.3. Restrictions on the Use of Digital Teaching Tools

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Araújo-Soares, V.; Hankonen, N.; Presseau, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Sniehotta, F. Developing Behavior Change Interventions for Self-Management in Chronic Illness. Eur. Psychol. 2019, 24, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calma, K.R.; Halcomb, E.; Stephens, M. The impact of curriculum on nursing students’ attitudes, perceptions and preparedness to work in primary health care: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Lasiter, S.; Ellis, R.B.; Buelow, J.M. Chronic disease self-management: A hybrid concept analysis. Nurs. Outlook 2015, 63, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connell, S.; Mc Carthy, V.J.C.; Savage, E. Frameworks for self-management support for chronic disease: A cross-country comparative document analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving Chronic Illness Care: Translating Evidence into Action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newson, J.T.; Huguet, N.; Ramage-Morin, P.L.; McCarthy, M.J.; Bernier, J.; Kaplan, M.S.; McFarland, B.; Newsom, J.T. Health behaviour changes after diagnosis of chronic illness among Canadians aged 50 or older. Public Health Rep. 2012, 23, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry, M. Today’s Health Problems and Health Education. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivelä, K.; Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H.; Kääriäinen, M. The effects of health coaching on adult patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 97, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohl, S.J.; Birdee, G.; Elam, R. Complementary Tools to Empower and Sustain Behavior Change: Motivational interviewing and mindfulness. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 10, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, H.; Ziaee, E.S.; Golshiri, P. Nurses’ consultative role to health promotion in patients with chronic diseases. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Gentry, D.; Klesges, L. Innovations in public health education: Promoting professional development and a culture of health. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, S44–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vijn, T.W.; Fluit, C.R.M.G.; Kremer, J.A.M.; Beune, T.; Faber, M.J.; Wollersheim, H. Involving Medical Students in Providing Patient Education for Real Patients: A Scoping Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadgaran, S.A.; Parvizy, S.; Peyrovi, H. Passing through a rocky way to reach the pick of clinical competency: A grounded theory study on nursing students’ clinical learning. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2012, 17, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Nieman, L.Z. A preclinical training model for chronic care education. Med. Teach. 2007, 29, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhlmiller, C.M.; Tolchard, B. Developing a student-led health and wellbeing clinic in an underserved community: Collaborative learning, health outcomes and cost savings. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shemtob, L. Should motivational interviewing training be mandatory for medical students? Med. Educ. Online 2016, 21, 31272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadeghi, R.; Heshmati, H. Innovative methods in teaching college health education course: A systematic review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeezadeh, D.; Heshmati, H. Integration of Health Education and Promotion Models for Designing Health Education Course for Promotion of Student’s Capabilities in Related to Health Education. Iran. J. Public Health 2018, 47, 1432–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Masic, I. E-Learning as New Method of Medical Education. Acta Inform. Medica 2008, 16, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaona, A.; Banzi, R.; Kwag, K.H.; Rigon, G.; Cereda, D.; Pecoraro, V.; Tramacere, I.; Moja, L. E-learning for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD011736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manallack, D.T.; Yuriev, E. Ten simple rules for developing a MOOC. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1005061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyles, C. Is there a MOOC in your future? Can. Vet. J. 2013, 54, 721–724. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, K.; Alturkistani, A.; Carter, A.; Stenfors, T.; Blum, E.; Car, J.; Majeed, A.; Brindley, D.; Meinert, E. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) Evaluation Methods: Protocol for a Systematic Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e12087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guze, P.A. Using Technology to Meet the Challenges of Medical Education. Trans. Am. Clin. Clim. Assoc. 2015, 126, 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Ashouri, E.; Sheikhaboumasoudi, R.; Bagheri, M.; Hosseini, S.A.; Elahi, N. Improving nursing students’ learning outcomes in fundamentals of nursing course through combination of traditional and e-learning methods. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2018, 23, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.S.; Kunz, R.; Kleijnen, J.; Antes, G. Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, J.J.; Malik, K.M.; Burnie, S.J.; Endicott, A.R.; Busse, J. What is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 2012, 56, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, M.P.; Angelini, L.; Henriques, H.R.; El Kamali, M.; Baixinho, C.; Balsa, J.; Félix, I.B.; Khaled, O.A.; Carmo, M.B.; Cláudio, A.P.; et al. Conversational Agents for Health and Well-being Across the Life Course: Protocol for an Evidence Map. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e26680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, OR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechtsen, N.J.W.; Poulsen, K.W.; Svensson, L.Ø.; Jensen, L.; Holst, J.J.; Torekov, S.S. Health care professionals from developing countries report educational benefits after an online diabetes course. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basak, T.; Demirtas, A.; Iyigun, E. The effect of simulation based education on patient teaching skills of nursing students: A randomized controlled study. J. Prof. Nurs. 2019, 35, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolesta, S.; Chmil, J.V. Interprofessional Education among Student Health Professionals Using Human Patient Simulation. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014, 78, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonito, S.R. The usefulness of case studies in a Virtual Clinical Environment (VCE) multimedia courseware in nursing. J. Med. Investig. 2019, 66, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowers, R.; Tunney, R.; Kelly, K.; Mills, B.; Trotta, K.; Wheeless, C.N.; Drew, R. Impact of Standardized Simulated Patients on First-Year Pharmacy Students’ Knowledge Retention of Insulin Injection Technique and Counseling Skills. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.; McLaughlin, D. Using simulated patients as a learning strategy to support undergraduate nurses to develop patient-teaching skills. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLea, D.; Shrader, S.; Phillips, C. A Week-Long Diabetes Simulation for Pharmacy Students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2010, 74, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isaacs, D.; Roberson, C.L.A.; Prasad-Reddy, L. A Chronic Disease State Simulation in an Ambulatory Care Elective Course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2015, 79, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolanczyk, D.M.; Borchert, J.S.; Lempicki, K.A. Focus group describing simulation-based learning for cardiovascular topics in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2019, 11, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moule, P.; Pollard, K.; Armoogum, J.; Messer, S. Virtual patients: Development in cancer nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilha, J.M.; Machado, P.P.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Ribeiro, R.; Vieira, F.; Costa, P. Easiness, usefulness and intention to use a MOOC in nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 97, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowart, K.; Updike, W.H. Pharmacy student perception of a remote hypertension and drug information simulation-based learning experience in response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 4, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, S.R.; Mujica, F.C.; Kleinheksel, A. Demographic and spatial trends in diabetes-related virtual nursing examinations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 222, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweigart, L.; Burden, M.; Carlton, K.H.; Fillwalk, J. Virtual Simulations across Curriculum Prepare Nursing Students for Patient Interviews. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2014, 10, e139–e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, D.; Wombwell, E.; Russell, E.; Caligiuri, F. High-Fidelity Patient Simulation Series to Supplement Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2010, 74, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeffries, P.R.; Rizzolo, M.A. Designing and Implementing Models for the Innovative Use of Simulation to Teach Nursing Care of Ill Adults and Children: A National, Multi-Site, Multi-Method Study; National League for Nursing: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Unver, V.; Basak, T.; Watts, P.; Gaioso, V.; Moss, J.; Tastan, S.; Iyigun, E.; Tosun, N. The reliability and validity of three questionnaires: The Student Satisfaction and Self-Confidence in Learning Scale, Simulation Design Scale, and Educational Practices Questionnaire. Contemp. Nurse 2017, 53, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsell, G.; Bligh, J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS). Med. Educ. 1999, 33, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, R.M.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Funnell, M.M.; Gruppen, L.D. The Third Version of the Diabetes Attitude Scale. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 1, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: Development and test. Decis. Sci. 1996, 27, 451–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and Emotion into the Technology Acceptance Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aebersold, M.; Tschannen, D.; Bathish, M. Innovative Simulation Strategies in Education. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 765212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gleason, K.T.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Wu, A.W.; Kearns, R.; Pronovost, P.; Aboumatar, H.; Himmelfarb, C.R.D. Massive open online course (MOOC) learning builds capacity and improves competence for patient safety among global learners: A prospective cohort study. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 104, 104984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Shellenbarger, T. Gamification of Nursing Education with Digital Badges. Nurse Educ. 2018, 43, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturkistani, A.; Lam, C.; Foley, K.; Stenfors, T.; Blum, E.R.; Van Velthoven, M.H.; Meinert, E. Massive Open Online Course Evaluation Methods: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, R.M.; Najjar, J.; Derntl, M.; Leony, D.; Neumann, S.; Oberhuemer, P.; Totschnig, M.; Simon, B.; Gutierrez, I.; Kloos, C.D. Aligning assessment with learning outcomes in outcome-based education. In Proceedings of the IEEE EDUCON 2010 Conference, Madrid, Spain, 14–16 April 2010; pp. 1239–1246. [Google Scholar]

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Introduction to Student Learning Outcomes Assessment for Continuing Program Improvement; Office of Institutional research and Assessment: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, Z.S. Framework for an effective assessment: From rocky roads to silk route. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumway, J.; Harden, R. AMEE Guide No. 25: The assessment of learning outcomes for the competent and reflective physician. Med. Teach. 2003, 25, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, H.A.; Barrett, L.C. Your teaching strategy matters: How engagement impacts application in health information literacy instruction. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2017, 105, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dolan, E.L.; Collins, J.P. We must teach more effectively: Here are four ways to get started. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 2151–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Shao, T.; Liu, C.; Shao, P.; Bishwajit, G.; Feng, D.; Feng, Z. Factors Influencing Health Knowledge and Behaviors among the Elderly in Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axley, L. The integration of technology into nursing curricula: Supporting faculty via the technology fellowship program. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2008, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramnanan, C.J.; Pound, L.D. Advances in medical education and practice: Student perceptions of the flipped classroom. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiou, S.-F.; Su, H.-C.; Liu, K.-F.; Hwang, H.-F. Flipped Classroom: A New Teaching Strategy for Integrating Information Technology into Nursing Education. Hu Li Za Zhi J. Nurs. 2015, 62, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, L.M.C.; Arias, J.A.T.; Serna, M.D.A.; Bedoya, J.W.B.; Burgos, D. Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genlott, A.A.; Grönlund, Å.; Viberg, O. Disseminating digital innovation in school—leading second-order educational change. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 3021–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williamson, K.M.; Muckle, J. Students’ Perception of Technology Use in Nursing Education. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2018, 36, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Population | Students (nursing, sports science, and pharmacy) |

| Intervention | RQ 1: MOOC, e-learning, simulation in the field of chronic diseases RQ 2: Assessment instruments |

| Outcomes | Outcomes of behavior change support education (knowledge, motivation, engagement, skills, learning outcomes, etc.) |

| Study design | Quantitative (e.g., case studies, randomized controlled trials, and controlled trials); qualitative (e.g., interview, questionnaire, and focus groups); and mixed method studies |

| Language | English language |

| Time frame | 2000–2021 |

| Access | / |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Substantive inadequacy; records involving students from other professional fields; records in other languages; and reviews, comments, and protocols | |

| No. | Author, Year | Type of Study | MMAT Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albrechtsen et al., 2017 [35] | QUAN descriptive study | 80% |

| 2 | Basak et al., 2019 [36] | QUAN single-blinded RCT | 90% |

| 3 | Bolesta et al., 2014 [37] | QUAN descriptive study | 80% |

| 4 | Bonito 2019 [38] | QUAL study | 80% |

| 5 | Bowers et al., 2017 [39] | QUAN descriptive study single-blinded, single-center, cluster RS | 90% |

| 6 | Coleman & McLaughlin 2019 [40] | MMS | 60% |

| 7 | Delea et al., 2010 [41] | QUAN descriptive study | 70% |

| 8 | Isaacs et al., 2015 [42] | MMS | 90% |

| 9 | Kolanczyk et al., 2019 [43] | MMS | 80% |

| 10 | Moule et al., 2015 [44] | MMS | 70% |

| 11 | Padilha et al., 2021 [45] | QUAN descriptive study | 80% |

| 12 | Pharm Cowart et al., 2021 [46] | MMS | 80% |

| 13 | Schultze et al., 2019 [47] | QUAN descriptive study | 80% |

| 14 | Sweigart et al., 2014 [48] | MMS | 50% |

| 15 | Vyas et al., 2010 [49] | QUAN descriptive study | 70% |

| No. | Assessment Instruments and Short Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | The post-course questionnaire included nine questions. The first eight were demographic. Question 9 consisted of 15 statements that collected data on the participant’s professional benefits from the course. |

| 2 | The SSSC [50,51] includes 13 items but has been reduced to 12 due to Turkish adaptation. Participants were rated on a 5-point scale. The SDS [50,51] ordered 20 items in five subcategories. Based on the literature, a 15-item performance assessment checklist of teaching skills was prepared. The feedback form contained five questions. |

| 3 | Pre-laboratory and post-laboratory survey instrument was created using a modification of RIPLS [52] and included 19 points, which used a 5-point Likert scale to assess students’ readiness for interprofessional learning. |

| 4 | A self-administered questionnaire with open-ended questions. |

| 5 | A 15-point checklist was used to assess each appropriate insulin pen counseling and injection technique component. All elements were evaluated in the form of yes/no. |

| 6 | Short five-item anonymous pro forma consisted of four open questions and one closed question. The closed-ended questions assessed by participants on a five-point scale evaluated the learning experience. With an open-ended question, they wanted to determine students’ perceptions of what was helpful to them about this simulation, how they could improve their experience, and whether any other topic they found beneficial to include in the simulated curriculum. |

| 7 | DAS-3 [53] included 33 questions, and questions consisted of confidence in diabetes education skills had seven questions. Students answered the questions using a 5-point Likert scale |

| 8 | Data Collection Sheet Follow-Up Visit; Chronic Disease State Reflection Questions; reflections and SOAP notes. The questionnaire included 11 targeted questions on simulating chronic disease status and used a 5-point Likert scale for assessment. |

| 9 | Focus groups and surveys. The survey questionnaire included eight questions about the simulation methods used for cardiac simulations. |

| 10 | Questionnaire, review about a virtual patient, and comments. |

| 11 | The questionnaire was based on a questionnaire Davis Technology Acceptance Model [54,55] and based on ease-of-use perception [56] |

| 12 | Pre- and post-surveys questionnaire with quantitative and qualitative questions. |

| 13 | Entries data included demographic data and four specific factors necessary for determining the perception of diabetes in nursing students (number of clinical findings identified by students during the examination with the virtual patient, the total number of empathic statements shared with the virtual patient, the total number patient education statements given to the patient, and the overall outcome of the clinical inference). |

| 14 | Computerized evaluation of each of the virtual experiences. |

| 15 | Pre-simulation and post-simulation quizzes with 5–15 questions specific to each simulation scenario were used to assess whether students’ knowledge increased through participation in the simulation. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gosak, L.; Štiglic, G.; Budler, L.C.; Félix, I.B.; Braam, K.; Fijačko, N.; Guerreiro, M.P.; Lorber, M. Digital Tools in Behavior Change Support Education in Health and Other Students: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010001

Gosak L, Štiglic G, Budler LC, Félix IB, Braam K, Fijačko N, Guerreiro MP, Lorber M. Digital Tools in Behavior Change Support Education in Health and Other Students: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2022; 10(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleGosak, Lucija, Gregor Štiglic, Leona Cilar Budler, Isa Brito Félix, Katja Braam, Nino Fijačko, Mara Pereira Guerreiro, and Mateja Lorber. 2022. "Digital Tools in Behavior Change Support Education in Health and Other Students: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 10, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010001

APA StyleGosak, L., Štiglic, G., Budler, L. C., Félix, I. B., Braam, K., Fijačko, N., Guerreiro, M. P., & Lorber, M. (2022). Digital Tools in Behavior Change Support Education in Health and Other Students: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010001