Abstract

Herein, we considered the Schrödinger operator with a potential q on a disk and the map that associates to q the corresponding Dirichlet-to-Neumann (DtN) map. We provide some numerical and analytical results on the range of this map and its stability for the particular class of one-step radial potentials.

1. Introduction

Let be a bounded domain with smooth boundary . For each , consider the so called Dirichlet-to-Neumann map (DtN) given by:

where u is the solution of the following problem:

and denotes the normal derivative of u on the boundary .

Note that the uniqueness of u as solution of (2) requires that 0 is not a Dirichlet eigenvalue of . A sufficient condition to guarantee that is well defined is to assume , the first Dirichlet eigenvalue of the Laplace operator in , since, in this case, the solution in (2) is unique. We assume that this condition holds and lets us define the space

In this work, we were interested in the following map:

This has an important role in inverse problems, where the aim is to recover the potential q from boundary measurements. In practice, these boundary measurements correspond to the associated DtN map, and therefore, the mathematical statement of the classical inverse problem consists of the inversion of .

It is known that is one-to-one as long as with (see [1]). Therefore, the inverse map can be defined in the range of . There are, however, two related important and difficult questions that are not well understood: A characterization of the range of and its stability, i.e., a quantification of the difference of two potentials, in the topology in terms of the distance of their associated DtN maps. Obviously, this stability will affect the efficiency of any inversion or reconstruction algorithm to recover the potential from the DtN map (see [2] and [3]).

The first question, i.e., the characterization of the range of is widely open. Tothe best of our knowledge, the further result is due to [4], where a characterization is obtained for the adherence, with respect to the weak topology in , of the sequence of eigenvalues associated with the orthogonal basis of eigenvectors . Here, is the space of sequences , such that This topology is not the usual one in and it is not easy to interpret how the adherence enlarges this set. Furthermore, the characterization does not give much practical information on the range, as, for instance, the convexity or accurate bounds on the eigenvalues. In fact, characterizing such properties is one of the main motivations of this work, since we could establish easily a priori if a desired linear map in can be associated with a DtN map. On the contrary, we have to take into account that in practice, the DtN map is estimated from physical measurements, which are subject to errors and may provide only partial information. A precise knowledge of the range of is useful to find the best DtN map that fits the measurements and to design an inversion algorithm in such situations.

Concerning the stability, it is well known that the problem is ill posed and that the most we can expect is logarithmic stability in general (see [5]). There are more explicit results when we assume that the potential q has some smoothness. In particular, if with , the following stability condition is known (see [1]):

where for some constants . Stronger stability conditions are known in some particular cases. For example, in [6], it was shown that when q is piecewise constant and the components where it takes a constant value are fixed and satisfy some technical conditions, the stability is Lipschitz, i.e., there exists a constant , such that:

In this work, we tried to understand better the situation by considering the simplest case of a disk with one-step radial potentials q. More precisely, we provide some results on the range of and its stability when we restrict to the particular case and given by:

where is the characteristic function of the interval . Note that F is a two-parametric family depending on and b.

It is worth mentioning that, as we show below, the solution of (2) is unique for all and , and therefore, the DtN map is well defined for all of these one-step potentials. In other words, 0 is not an eigenvalue of the operator and, in particular, we do not need to restrict ourselves to the constraint . However, we still restrict ourselves to the bounded set F to simplify.

Even in this simple case, a complete analytic answer to the previous questions (range of the DtN map and sharp stability conditions) is unknown. Therefore, we also considered a numerical approach based on a discrete sampling of the set F. Given an integer , we define and:

Note that has functions from F. As , we can obtain a better description of F and, in particular, we should recover the properties for .

The main contributions of this paper are given below:

- Concerning the stability of , we show that it fails in the sense that inequality (4) does not hold for any continuous function with . The proof is an adaptation of the analogous result for the conductivity problem obtained in [7]. In fact, we consider—as potential—the same piecewise constant radial conductivity used in [7]. The stability constant blows up when the support of the inner disk where the value of the potential is constant becomes zero.

- We now consider fixed and we define the set as:We prove that if , there is stability of the DtN map with respect to the position of the discontinuity b for potentials in . More precisely, we obtain a stability constant depending on , which is uniformly bounded for and fixed (see Theorem 3 below). Note, however, that this constant blows up as .This stability result does not give information about the stability with respect to the norm of the potentials, but it provides stability with respect to the norm, which is sensitive to the position of the discontinuities, when and . In fact, we show numerical evidence of such stability when considering potentials in F.

- For the range of , we give a characterization in terms of the first two eigenvalues of the DtN map. We also analyze the region where the stability constant is larger, and, therefore, the potentials for which any recovering algorithm for q from the DtN map will have more difficulties.

We mention that a similar analysis can be conducted for the closely related—and more classical—conductivity problem, where (2) is replaced by:

and the Dirichlet-to-Neumann map, or voltage-to-current map, is given by:

In this case, the relationship between piecewise constant radial conductivities and the eigenvalues of the DtN map is known [8] through a suitable recurrence formula. However, there is not a direct transformation that relates both problems, and the analysis must be done specifically for this case.

We refer to the review paper [9] and the references therein for theoretical results on the DtN map in this case.

The rest of this paper is divided as follows: In Section 2 below, we characterize the DtN map in terms of its eigenvalues using polar coordinates. In Section 3 and Section 4, we analyze the stability and range results, respectively. In Section 5, we briefly describe the main conclusions, and finally, Section 5 contains the proofs of the theorems stated in the previous sections.

2. The Dirichlet-to-Neumann Map

In this section, we characterize the Dirichlet-to-Neumann map in the case of a disk. System (2) in polar coordinates reads:

where is a periodic function.

An orthonormal basis in is given by . Here, we use this complex basis to simplify the notation, but in the analysis below, we only consider the subspace of real valued functions. Therefore, any function can be written as:

and . Associated with this basis, we define the usual Hilbert spaces: , for , as

In the above basis, the Dirichlet-to-Neumann map turns out to be diagonal. In fact, we have the following result:

Theorem 1.

Let Ω be the unit disk and . Then:

where:

and are the Bessel functions of the first kind.

Note that the range of , when restricted to F, is characterized by the set of sequences of the form (15) and (16) for all possible . In particular, when , we have:

and this sequence must be in the range of .

The norm of , when restricted to F, is given by:

Proof of Theorem 1.

We first compute in (14). As the boundary data at in (11) is the constant , we assume that is radial, i.e., . Then, should satisfy:

For , we solve the ODE with the boundary data at , while for , we use the boundary data at . In the first case, the ODE is the Bessel ODE of order 0, and therefore, we have:

where is the Bessel function of the first kind and and are constants. These are computed by imposing continuity of and at . In this way, we obtain:

Solving the system for and and taking into account that , we easily obtain (14).

Similarly, to compute in (14), we have to consider in (11), and therefore, we assume that the solution can be written in separate variables, i.e., . Then, must satisfy:

As in the case of , for , we solve the ODE with the boundary data at , while for , we use the boundary data at . We have:

where and are constants. These are computed by imposing continuity of and at . In this way, we obtain:

Solving the system for and , we obtain, in particular:

We simplify this expression using the well-known identity:

and we obtain:

Now, taking into account that , we easily obtain (14). □

Remark 1.

In this proof of Theorem 1, we do not use the restriction that satisfies the potentials in F. In fact, the statement of the theorem still holds for any step potential, as in F, but with any arbitrary large .

3. Stability

In this section, we focus on the stability results for the map . Some results are analytical and they are stated as theorems. The proofs are given in Appendix A. We divided this section in three subsections, where we consider the negative stability result for norm, and some partial results when we consider the subsets defined by:

and defined in (8).

3.1. Stability for

The first result in this section is the lack of any stability property when . In particular, we prove that inequality (4) fails for any continuous function with .

Theorem 2.

Given , there exists a sequence , such that for all , while:

This result contradicts any possible stability result of the DtN map at . Roughly speaking, the idea is that the eigenvalues of , given in Theorem 1 above, depend continuously on b, unlike the norm of the potentials. A detailed proof of the Theorem 2 is given in the Appendix A below.

3.2. Partial Stability

We now give two partial stability results when we fix b and , respectively.

Theorem 3.

Given and , we have:

On the contrary, given and , we have:

where .

The proof of this theorem is in the Appendix A below.

Inequality (22) provides a Lipschitz stability result for when b is fixed. This result is not new, since this situation enters in the framework in [6], as q takes constant values in fixed regions. The contribution here is in the dependence of the Lipschitz constant on the parameter b, which is associated with the size of the region, where q takes a different constant value. An estimate (22) shows also that the lack of Lipschitz stability is related to variations in the position of the discontinuity, which is the main idea in the negative result given in Theorem 2.

A numerical quantification of this Lipschitz stability for b fixed is easily obtained. We fix and consider:

and for :

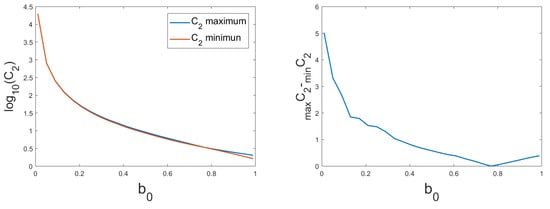

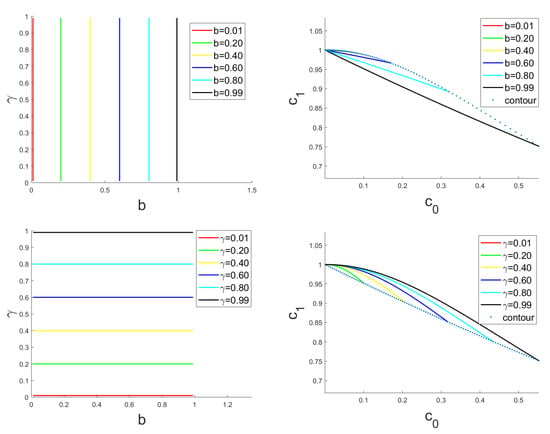

then, remains bounded as for all . In Figure 1, we show the behavior of when for different values of . To illustrate the behavior with respect to , we plot on the left-hand side of Figure 1 the graphs of the functions:

Figure 1.

Numerical estimate of the stability constant in (24) for . To illustrate the behavior on b, we plotted the maximum and minimum value when with respect to b in logarithmic scale (left), and its range in normal scale (right).

We see that both constants become larger for small values of b. We also see that both graphs are close in this logarithmic scale. However, the range of the interval is not small, as shown on the right-hand side of Figure 1.

Concerning inequality (23) in Theorem 3, it provides a stability result for with respect to the position of the discontinuity. In particular, this provides Lipschitz stability if we consider a norm for the potentials that is sensitive to the position of the discontinuity. This is not the case for the norm, but it is true for the -norm for some . For example, when :

We can also check this numerically:

is bounded as and , where:

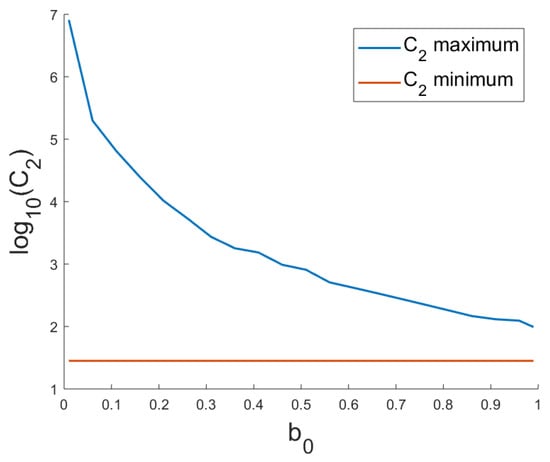

In Figure 2, we show the values when . We can observe that the constant blows up as .

Figure 2.

for when .

4. Range of the DtN Map

In this section, we are interested in the range of when , i.e., the set of sequences of the form (15) and (16) for all possible .

As F is a bi-parametric family of potentials, it is natural to check if we can characterize the family with only the first two coefficients and . In this section, we give numerical evidence of the following facts:

- The first two coefficients, and , in (15) and (16) are the most sensitive with respect to and, therefore, are the more relevant ones to identify b and from the DtN map.

- The function:is injective. This means, in particular, that the DtN map can be characterized by the coefficients and , when restricted to functions in . We also illustrate the set of possible coefficients .

- The lack of stability for is associated with a higher density of points in the range of . This occurs when either b or is close to zero.

4.1. Sensitivity of

To analyze the relevance and sensitivity of the coefficients to identify the parameters , we computed their range when , and the norm of their gradients. As we can see in Table 1, the range decreases for large n. This means that, for larger values of n, the variability of is smaller and they are likely to be less relevant to identify q.

Table 1.

Range of the coefficients, i.e., for each , the range is defined as .

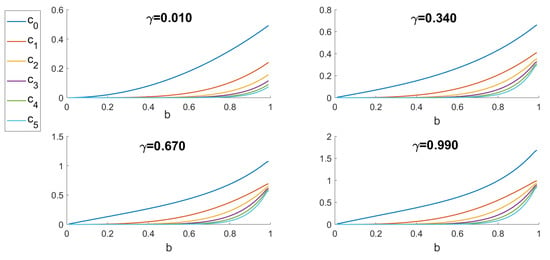

However, even if the range of becomes smaller for large n, they could be more sensitive to small perturbations in and this would make them useful to distinguish different potentials. However, this is not the case. In Figure 3, we show that for the given values of and , the gradients of the first two coefficients, with respect to , are larger than the others. Therefore, we conclude that the two first coefficients, and , are the most sensitive and, therefore relevant to identify the potential q.

Figure 3.

Norm of the gradient of the coefficients in terms of for different values of . We can see that the gradients of higher coefficients are smaller than those of the first two. We can also observe that these gradients become small for small values of b.

We also see in Figure 3 that these gradients are very small for . This means, in particular, that identifying potentials with small b from the DtN map should be more difficult.

4.2. Range of the DtN in Terms of

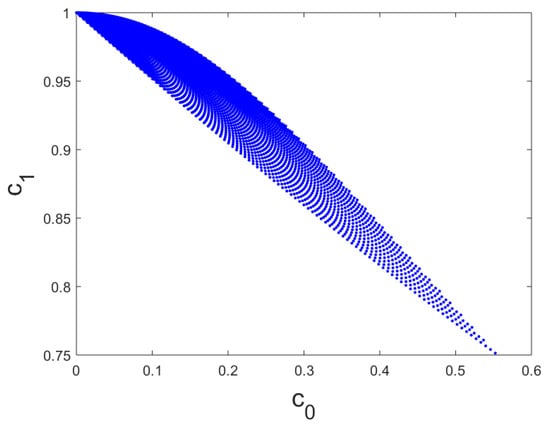

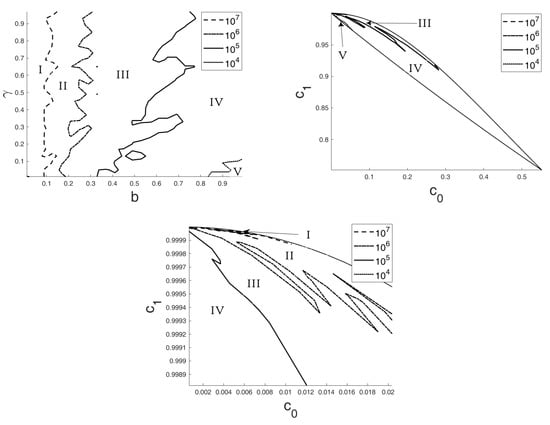

Now, we focus on the range of the DtN in terms of the relevant coefficients , i.e., the range of the map in (27): . In Figure 4, we show this range.

Figure 4.

Range of the discrete Dirichlet-to-Neumann (DtN) map in (27) (.

Coordinate lines for fixed and b are given in Figure 5. We can observe that is a convex set between the curves:

Figure 5.

Coordinate lines of the map defined in (27) (. The upper figure contains the coordinate lines associated with b constant, while the lower one corresponds to constant.

Note also that in the plane, the length of the coordinate lines associated with b constant are segments that become smaller as . Analogously, the length of those associated with constant become smaller as . Thus, the region where either b or are small produces a higher density of points in the range of . This corresponds to the upper left part of its range (see Figure 4). On the contrary, this Figure provides numerical evidence of the injectivity of as well. In fact, any point inside is the intersection of two coordinate lines associated with some unique and .

The higher density of points in the upper left hand-side of the range of should correspond to potentials q with a large stability constant , defined as:

In Figure 6, we show the level sets of for and different . The region with a larger constant corresponds to small values of b (upper right figure) and larger values of (upper left and lower figures). On the contrary, the region with a lower stability constant is for b close to , which corresponds to the lower part of the range of when is small.

Figure 6.

Level sets of the for and in terms of (upper left) and in terms of (upper right), and a close up of the upper left region in this last figure is in the lower figure. Regions separated by level sets are indicated: Region I corresponds to the potentials with a stability constant larger that , region II corresponds to those with a stability constant lower that but larger than , and so on.

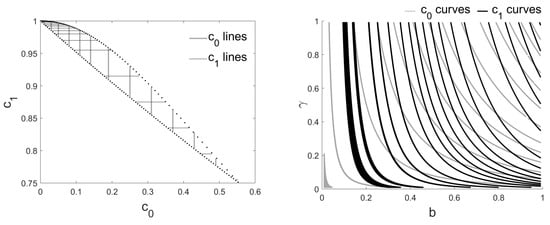

It is interesting to analyze the set of potentials with the same coefficient or . We provide, in Figure 7, the coordinate lines of the inverse map . When increasing the value of either (light lines) or (dark lines), we obtain lines closer to the left part of the region. We can see that the angle between coordinate lines becomes very small for small b. In this region, close points could be the intersection of the coordinate lines associated with not so close parameters . This agrees with the region where the stability constant is larger.

Figure 7.

Coordinate lines of the map defined in (27).

5. Conclusions

We considered the relationship between the potential in the Schrödinger equation and the associated DtN map in one of the simplest situations, i.e., for a subset of radial one-step potentials in two-dimension. In particular, we focused on two difficult problems: The stability of the map (defined in (3)) and its range. In this case, the map is easily characterized in terms of the Bessel functions and this allows us to give some analytical and numerical results for these problems. We proved the lack of any possible stability result by adapting the argument in [7] [Alessandrini, 1988] for the conductivity problem. We also obtained some partial Lipschitz stability when the position of the discontinuity is fixed in the potential, as well as numerical evidence of the stability with respect to the norm. Finally, we characterized numerically the range of in terms of the first two eigenvalues of the DtN map and provided some insight into the regions where the stability of is worse. As a future line of work, it could be interesting to consider the problem in a more complicated stage, for instance, one can study not only one-step radial potentials q in the problem, but could add more steps into the definition of the potentials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and S.M.; Formal analysis, S.L. and S.M.; Investigation, S.L. and S.M.; Methodology, S.L. and S.M.; Visualization, S.L.; Writing—original draft, S.L. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received of the project PDI2019-110712GB-100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The first author was partially supported by project MTM2017-85934-C3-3-P from the MICINN (Spain). The second author was partially supported by project PDI2019-110712GB-100 of the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain. We want to thank to J.A. Barceló and C. Castro their contribution to the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

To prove Theorems 2 and 3, we need the following technical results regarding the the Bessel functions.

Lemma A1.

Let be the Bessel functions of the first kind of order . It is well known (see [10]) that:

where:

For and the following holds:

and:

More explicit estimates for and are given by:

Proof.

The following lemma is used in the proof of Theorem 3.

Lemma A2.

For and , we have:

and:

Proof.

The previous estimates are a consequence of (A6) and the inequality:

□

Proof of Theorem 2.

We take without loss of generality. For , we consider the fixed potential:

and a positive integer satisfying . We define the potentials:

with .

If , by (15) and (16), we have:

We start by estimating .

Since is a decreasing function in , we have:

A simple calculation and this inequality gives us:

where the symbol ≲ denotes that the left-hand side is bounded by a constant times the right-hand one. Thus, combining the mean value theorem, the identity , the fact that and (A2), we easily get:

Remark A1.

Proof of Theorem 3.

□

Proof of (22).

References

- Blȧsten, E.; Imanuvilov, O.Y.; Yamamoto, M. Stability and uniqueness for a two-dimensional inverse boundary value problem for less regular potentials. Inverse Probl. Imaging 2015, 9, 709–723. [Google Scholar]

- Tejero, J. Reconstruction and stability for piecewise smooth potentials in the plane. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2017, 49, 398–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, J. Reconstruction of rough potentials in the plane. Inverse Probl. Imaging 2019, 13, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingerman, D.V. Discrete and continuous Dirichlet-to-Neumann maps in the layered case. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2000, 31, 1214–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandache, N. Exponential instability in an inverse problem for the Schrödinger equation. Inv. Probl. 2001, 17, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, E.; De Hoop, M.V.; Qiu, L. Lipschitz stability of an inverse boundary value problem for a Schrödinger-type equation. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2013, 45, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, G. Stable determination of conductivity by boundary mea- surements. Appl. Anal. 1988, 27, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Siltanen, S. Linear and Nonlinear Inverse Problems with Practical Applications; SIAM Computational Science and Engineering: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, G. Inverse problems: Seeing the unseen. Bull. Math. Sci. 2014, 4, 209–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafacos, L. Classical Fourier Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev, N.N. Special Functions and Their Applications; Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).