Abstract

This article presents a partially linear additive spatial error model (PLASEM) specification and its corresponding generalized method of moments (GMM). It also derives consistency and asymptotic normality of estimators for the case with a single nonparametric term and an arbitrary number of nonparametric additive terms under some regular conditions. In addition, the finite sample performance for our estimates is assessed by Monte Carlo simulations. Lastly, the proposed method is illustrated by analyzing Boston housing data.

1. Introduction

Linear regression is one of the most classic and widely used techniques in statistics. Linear regression models usually assume that the mean response is linear; however, this assumption is not always granted Fan and Gijbels [1]. A nonparametric model was proposed to more flexibly solve nonlinear problems encountered in practice. Partially linear additive regression model (PLARM) can be used to study the linear and nonlinear relationship between a response and its covariates simultaneously. Opsomer and Ruppert [2] first proposed the PLARM and presented consistent backfitting estimators for the parametric part. Manzan and Zerom [3] introduced a kernel estimator of the finite dimensional parameter in the PLARM and derived consistency and asymptotic normality of the estimators under some regular conditions. Zhou et al. [4] considered variable selection for PLARM with measurement error. Wei et al. [5] investigated the empirical likelihood method for the PLARM. Hoshino [6] proposed a two-step estimation approach of partially linear additive quantile regression model. Lou et al. [7] introduced sparse PLARM and discussed the model selection problem through convex relaxation. Liu et al. [8] presented the spline–backfitted kernel estimator of PLARM and studied statistical inference properties of the estimator. Manghi et al. [9] also discussed the statistical inference of the generalized PLARM.

The linear spatial autoregressive model, which extends the ordinary linear regression model in view of a spatially lagged term of the response variable, has been one of the most important statistical tools for modeling spatial dependence among the spatial units (Li and Mei [10]). Theories and estimation methods based on linear autoregressive models have attracted widespread attention and have been extensively studied (Anselin [11], Kelejian and Prucha [12], Elhorst [13], et al.). In the real world, highly nonlinear practice problems commonly exist between response variables and regressors, especially for spatial data. Su and Jin [14] investigated profile quasi-maximum likelihood estimation of a partially linear spatial autoregressive model. Su [15] proposed generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation of nonparametric spatial autoregressive (SAR) model, which included heteroscedasticity and spatial dependence in the error terms. Li and Mei [10] studied statistical inference of a profile quasi-maximum likelihood estimator based on the partially linear spatial autoregressive model in Su and Jin [14]. However, these models face the problem of “curse of dimensionality”, namely, their nonparametric estimation precision decreases rapidly as the dimension of explanatory variables increases. In order to overcome this drawback, some useful semiparametric SAR models with dimensional reduction functions, which include partially linear single-index, varying coefficient, and additive SAR models, have been developed in recent years. Sun [16] studied GMM estimators of single-index SAR models and their asymptotic distributions. Cheng et al. [17] not only extended the single-index SAR model to partially linear single-index SAR models, but they also explored GMM estimation of the model and asymptotic properties of estimators. Wei and Sun [18] proposed GMM estimation of varying coefficients in the SAR model and obtained asymptotic properties of estimators. Dai et al. [19] considered a quantile regression approach for partially linear varying coefficients in the SAR model and established asymptotic properties of estimators and test statistics. Du et al. [20] presented a partially linear additive SAR model, constructed GMM estimation of the model, and proved the asymptotic properties of estimators. To our best knowledge, research on the statistical inference of partially linear additive spatial error model (PLASEM) is still lacking. In this paper, we attempt to study GMM estimation of this model and statistical properties of estimators.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present the PLASEM and its corresponding estimation method. In Section 3, we derive the large sample properties under some regular assumptions. Some Monte Carlo simulations are conducted in Section 4 to assess the finite sample performance of estimates. The developed method is illustrated with the Boston housing price data in Section 5. Conclusions are summarized in Section 6. The detailed proofs are given in Appendix A.

2. Model and Estimation

2.1. Model Specification

Consider the following PLASEM:

where is the ith observation of response variable , is the ith observation of p dimensional exogenous regressor , is the jth observation of exogenous regressor , is a p dimensional linear regression coefficient, is a spatial auto-correlation coefficient, is an unknown smooth function, is regression disturbance, is non-stochastic spatial weight, and the ith innovation is independent with E and E. Furthermore, we assume E for identification purposes. Denote , and similarly for , and . We write the spatial weight matrix and the vectors of additive functions as and respectively. In matrix notation, Model (1) can be rewritten as

2.2. Estimation Procedures

We first study the simple case with , so Model (2) under consideration is

where . The specific estimation procedures are as follows:

- Step 1. The initial estimation of unknown function . Following the idea of “working independence” in Lin and Carroll, [21], the correlation structure of can be ignored when we estimate . Next, a local linear estimation method is used to fit unknown function . Let represent the equivalent kernels for the local linear regression at z, it can be written as , where , , with for kernel function and bandwidth h. Thus, we can obtain the initial estimator of :Let be the smoother matrix whose rows are the equivalent kernels; we have

- Step 2. The initial GMM estimation of . Let be an matrix of instrumental variables, where , and we have the moment conditions E. Now we replace in Model (3) by and get the corresponding moment functions:where , . Let be a positive definite constant matrix, we can choose initial estimator of by minimizing object functionIt is easy to see that

- Step 3. The estimation of parameters and . For notational convenience, let , , , similarly, we have and , where , , are the ith element of , , respectively. Therefore, we get the following equationsBy squaring (5) and then summing, squaring (6) and summing, multiplying (5) by (6), and summing, we obtain the following equations:Assumption 2 implies , noting that and , where denotes the trace operator, let , taking the expectations of Equation (7), we havewhere , .In general, and are unknown, we present the estimator of by the two-stage estimation in Kelejian and Prucha [12]. Let and , where is obtained from in the second step, and denote , , as the ith element of , , respectively. Thus, the estimators of and can be obtained respectively as follows:, .Then, the empirical form of Formula (8) iswhere can be viewed as a vector of regression residuals. It follows from Formula (9) that the empirical estimator of can be given byBased on Formula (10), the nonlinear least square estimator can also be defined by Kelejian and Prucha [12]Kelejian and Prucha [12] proved that both and are consistent estimators of . Hence, it does not matter which one is chosen as the estimator of . In the following study, we need only consider as an estimator of .

- Step 4. The final estimation of and . Applying a Cochrane–Orcutt type transformation to Model (3) yieldswhere and . Therefore, we get the final estimator of as follows:where and .Finally, we replace in Formula (4) by and obtain the final estimator of as

Now, let us discuss the case . We estimate unknown functions by the popular “backfitting” method (Buja et al. [22], Härdle and Hall, [23]), and estimation of unknown parameters is similar to the case . The detailed steps are described as follows:

- Step 1. The initial estimation of is fixed. Suppose that and are given, for any given , we can fit unknown function and its derivative by using local linear estimation method:where and . Let , then represents the smoother matrix for the local linear regression at observation . Like Opsomer and Ruppert [2], the smoother matrix is replaced by , where is an unit matrix and . Therefore, we get

- Step 2. The initial estimation of (). Based on backfitting algorithm, we choose the common Gauss–Seidel iteration, it schemes update one component at a time, based on the most recent components available Buja et al.( [22]). Let be estimation of the lth update for . Therefore, we haveIterate the above equation until convergence. Therefore, we obtainHastie and Tibshirani [24], Opsomer and Ruppert [25] proposed the backfitting estimator of in the bivariate additive model . Similar to Opsomer and Ruppert [2], Opsomer [26], we can get the estimators of additive part functions by solving the following normal equations:Generally, if the matrix is invertible, we may write the above estimators directly aswhere . Let is a partitioned matrix with an identity matrix as the jth “block” and zeros elsewhere. Then, we havewhere and . Next, we need the dimensional smoother matrix , which can be derived from the data generated by the modelBased on Lemma 2.1 in Opsomer [26], we know that the backfitting estimators convergence to a unique solution if for some . In this case, can be rewritten as

- Step 3. The initial GMM estimation of . Let be an matrix of instrumental variables (IV), and , we have the corresponding moment functionsLet be a positive definite constant matrix; we can obtain the initial estimator of by minimizingIt is easy to know that

- Step 4. The estimation of parameter of . Similar to Step 3 in the case , we get the estimator of by two-stage estimation in Kelejian and Prucha [12]. Denote as estimator of , we have

- Step 5. The final estimator of and . Applying a Cochrane–Orcutt type transformation to Model (2). Let and We can get the final estimator ofwhere and .By substituting into the expression (16), we obtain the final estimator of and respectively as

3. Asymptotic Properties

To provide a rigorous consistency and asymptotic normality of parametric and nonparametric components, we state the following basic regular assumptions.

3.1. Assumptions

Assumption 1.

- (1)

- The elements of spatial weight matrix are non-random, and all elements on the primary diagonal satisfy .

- (2)

- The matrix is nonsingular for all .

- (3)

- The matrices and are uniformly bounded in both row and column sums in absolute value for all .

Assumption 2.

- (1)

- The covariate is a non-stochastic matrix and has full row rank, and the elements of are uniformly bounded in absolute value.

- (2)

- The column vectors of covariate are i.i.d. random variables.

- (3)

- The instrumental variables matrix is uniformly bounded in both row and column sums in absolute value.

- (4)

- The innovation sequence satisfies for some small δ, where is a positive constant.

- (5)

- The density of random variable z is positive and uniformly bounded away from zero on its compact support set. Furthermore, both and are bounded on their support sets.

Assumption 3.

- (1)

- The kernel function is a bounded and continuous nonnegative symmetric function on its closed support set.

- (2)

- Let and , where l is a nonnegative integer.

- (3)

- The second derivative of exists and is bounded and continuous.

Assumption 4.

For notational simplicity, denote

- (1)

- , where is a positive semidefinite matrix.

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- .

- (4)

- .

- (5)

- .

Assumption 5.

As , and , .

Assumption 6.

- (1)

- The kernel function is a bounded and continuous nonnegative symmetric function on its closed support set.

- (2)

- Let and , where l is a nonnegative integer.

- (3)

- The second derivative of exists and is bounded and continuous.

Assumption 7.

Denote

- (1)

- .

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- .

- (4)

- .

Assumption 8.

As , and , , .

Remark 1.

Assumption 1 provides the basic features of the spatial weight matrix. In some empirical applications, it is a practice to have be row normalized, namely, . Assumption 2 concerns the features of the regressors, error term, instrumental variables and density function for the model. Assumption 3 concerns the kernel function and nonparametric function for the case . Assumptions 4–5 are necessary for the asymptotic properties of the estimator for the case . Assumptions 6–8 are corresponding conditions of kernel functions, bandwidths and asymptotic properties of the estimator for arbitrary nonparametric additive terms.

3.2. Asymptotic Properties

In the next subsection, we first discuss the asymptotic normality of estimators for the case with a single nonparametric term. We then study the asymptotic properties of estimators for an arbitrary number of nonparametric additive terms.

Theorem 1.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–4 hold, has a consistent estimator . Furthermore, we have

where .

Theorem 2.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–5 hold, we have

Theorem 3.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–5 hold and , we have

where .

Theorem 4.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–5 hold, we have

where is the (1,1) element of Γ and .

Theorem 5.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–2 and Assumptions 6–8 hold, we have

where .

Theorem 6.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–2 and Assumptions 6–8 hold, we have

Theorem 7.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–2 and Assumptions 6–8 hold and , we have

where .

Theorem 8.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–2 and Assumptions 6–8 hold, we have

where with .

4. Simulation Studies

In this section, we will illustrate the finite sample performance of our GMM estimators by Monte Carlo experiment results. Similar to Cheng et al. [15], we generate the spatial weight matrix according to Rook contiguity (Anselin [11], pp. 17–18). The data generating process comes from the following model:

where covariate is independently generated from multivariate normal distribution with and . Covariates and are independently generated from uniform distributions and , respectively. and . The innovations are independently generated from normal distribution . The true value . For comparison, three different values , and , which represent from weak to strong spatial dependence of the error terms, are investigated.

For the parametric estimates, the sample mean (MEAN), the sample standard deviation (SD) and mean square error (MSE) are used as the evaluation criteria. For the nonparametric function, we use the root of average squared error (RASE, as in Fan and Wu [27]) as the evaluation criterion

where grid point is fixed.

For bandwidth sequences, we use cross-validation to choose the optimal bandwidth. For all estimators, we use the standardized Epanechikov kernel . Furthermore, we select the instrumental variables matrix as set to . The sample sizes under investigation are . For each case, there are 500 repetitions using Matlab software.

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 report the finite sample performance for all estimates under three cases of spatial correlation coefficient , respectively. First, the biases of are slightly larger when sample size , but they decrease as sample size increases. SDs and MSEs for estimates of are small for all cases and have a downward trend as sample size increases. Second, the biases, SDs and MSEs for estimates of , and are small for all cases and decrease as sample size increases. Third, the MEANs and SDs of 500 RASEs fairly rapidly decrease as sample size increases.

Table 1.

The results of parametric estimates in Model (18) with .

Table 2.

The results of parametric estimates in Model (18) with .

Table 3.

The results of parametric estimates in Model (18) with .

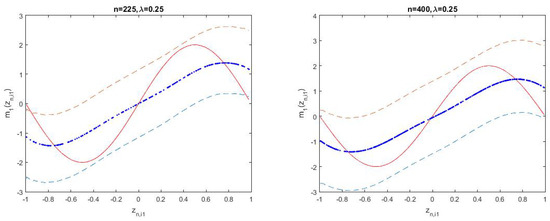

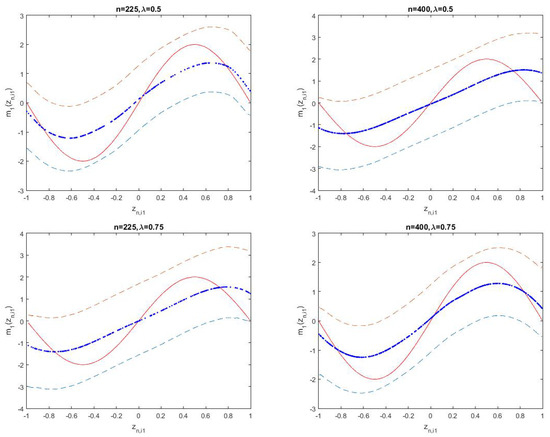

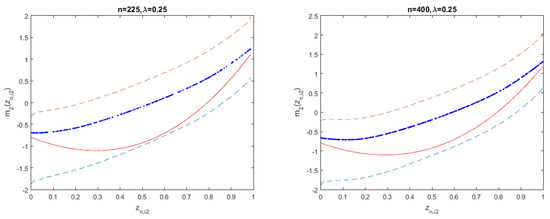

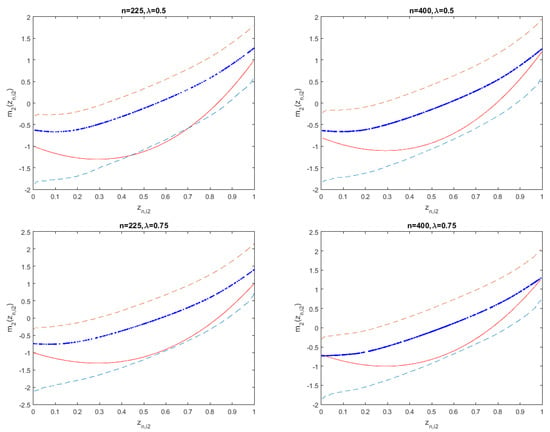

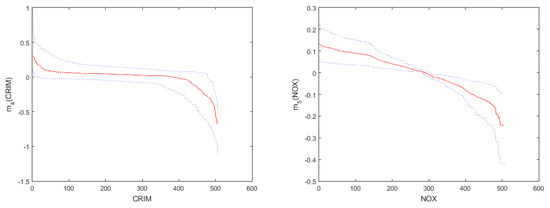

Figure 1 shows the fitted results and 95% confidence intervals of unknown function for three cases of when and , respectively. The short dashed and solid curves display the true unknown function and its estimates, respectively. The long dashed curves describe the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Figure 2 shows the corresponding fitted results of unknown function . By observing the fitting effect and confidence intervals of unknown functions in Figure 1 and Figure 2, we find that the small sample performances of nonparametric functions are good.

Figure 1.

The fitting results of in Model (18).

Figure 2.

The fitting results of in Model (18).

5. A Real Data Example

In this section, we will analyze the well-known Boston housing data in 1970 using the proposed estimation procedures in Section 2. The data set has 506 observations, 15 exogenous regressors and 1 response variable. It includes the following variables:

- MEDV: The median value of owner-occupied homes in USD 1000s.

- LON: Longitude coordinates.

- LAT: Lattitude coordinates.

- CRIM: Per capita crime rate by town.

- ZN: Proportion of residential land zoned for lots over 25,000 sq.ft.

- INDUS: Proportion of non-retail business acres per town.

- CHAS: Charles river dummy variable.

- NOX: Nitric oxides concentration.

- RM: Average number of rooms per dwelling.

- AGE: Proportion of owner-occupied units built prior to 1940.

- DIS: Weighted distances to five Boston employment centers.

- RAD: Index of accessibility to radial highways.

- TAX: Full-value property tax per USD 10,000.

- PTRATIO: Pupil–teacher ratio by town.

- B: 1000(B-0.63) where B is the proportion of blacks by town.

- LSTAT: Percentage of lower status of the population.

Zhang et al. [28] analyzed these data via the partially linear additive model. Moreover, they investigated this data set by using variable selection and concluded that variables RAD and PTRATIO have linear effects on the response variable MEDV; variables CRIM, NOX, RM, DIS, TAX and LSTAT have nonlinear effects on the response variable MEDV; and the other variables are insignificant and were removed from the final model. Based on the conclusion drawn by Du et al. [28] and Zhang et al. [20], the spatial effect was considered using the partially linear additive spatial autoregressive model. Cheng et al. [17] investigated these data using the partially linear single-index spatial autoregressive model.

In our real data analysis, based on the conclusions drawn by Cheng et al. [17] and Du et al. [20], we consider that the dependent variable is MEDV; variables RAD and PTRATIO have linear effects on the response variable MEDV; and variables CRIM, NOX, RM, DIS and LSTAT have nonlinear effects on the response variable MEDV. We consider the partially linear additive spatial error model as follows:

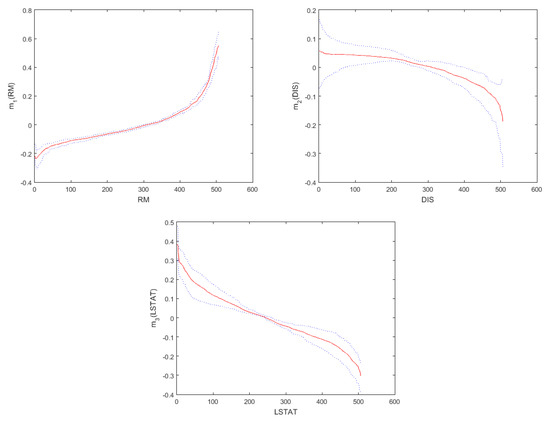

where the response variable , the covariates and , are the ith element of CRIM, NOX, RM, DIS and log(LSTAT), respectively. As in Cheng et al. [17] and Du et al. [20], logarithmic transformation of variables is taken to relieve the trouble caused by big gaps in the domain. The spatial weight matrix is calculated by the Euclidean distance in the light of longitude and latitude coordinates of any two houses. Moreover, the spatial weight matrix is normalized. Table 4 lists analysis results for the estimation of unknown parametric coefficients and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The function estimates of nonparametric components are displayed in Figure 3.

Table 4.

Estimation results of unknown parameters in Model (19).

Figure 3.

The estimates of the nonparametric functions in Model (19).

From Table 4, we can get the conclusions as follows. Firstly, the estimate of the spatial coefficient is 0.4689, the standard deviation 0.0916, and the mean square error is 0.0085 with a confidence interval that does not include 0, which shows that there exists a positive spatial relation among the regression disturbance term. Secondly, for the linear part, the regression coefficient for RAD is positive, which indicates that the housing price increases as the index of accessibility to radial highways increasing. The regression coefficient for PTRATIO is negative, which reveals that the pupil–teacher ratio by town has a negative effect on the housing price. Thirdly, for the nonlinear part, by observing Figure 3, we can obtain that the housing price would decrease as the other variables increase except RM. The variables CRIM, NOX, RM, DIS and log(LSTAT) have non-linear effects on the response, which is slightly different from the conclusion obtained by Du et al. [20]. The main reason is that our model has a different spatial structure compared with the model given in Du et al. [20].

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we present a partially linear additive spatial error model. This model not only can effectively avoid the “curse of dimensionality” in the nonparametric spatial autoregressive model and enhance the robustness of estimation, but it also investigates the spatial autocorrelation of error terms, and captures the linearity and nonlinearity between the response variable and the interesting regressors simultaneously. The local linear estimators of nonparametric additive components and GMM estimators of unknown parameters are constructed for the cases and , respectively. The consistency and asymptotic normality of estimators under some regular conditions are developed for both cases. Meanwhile, Monte Carlo simulation illustrates the good finite sample performance of estimators. The real data analysis implies that our proposed methodology can be used to fit Boston data well and is easy to perform in practice.

This paper focuses only on the independent errors with homoscedasticity. However, many real spatial data sets do not satisfy the conditions, and it is significant to extend this model to cases with heteroscedasticity. Furthermore, we have not considered the issue of variable selection in the model. These scenarios will be studied as future topics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.; methodology, J.C. and S.C.; software, S.C.; validation, S.C.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, J.C. and S.C.; resources, J.C.; data curation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, J.C.; visualization, J.C. and S.C.; supervision, J.C.; funding acquisition, J.C. and S.C. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NSF of Fujian Province, PR China (2018J05002, 2020J01170), Fujian Normal University Innovation Team Foundation, PR China (IRTL1704), Scientific Research Foundation of Chongqing Technology and Business University, PR China (2056015) and Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, PR China (KJQN202000843).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Lemma A1.

(Su [15]) The row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value for sufficiently large n, and the elements satisfy .

Lemma A2.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–3 hold, we have

Proof of Lemma A2.

It follows from and that

where , and . According to Assumption 3, we get

Similarly, and . Therefore, we obtain

□

Lemma A3.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–3 hold, we have

Proof of Lemma A3.

Denote , by Assumption 1, it is easy to know that the row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value. Namely, there exists a positive constant such that . Noting that

where and . Clearly, and . It follows by Assumption 1 and Assumption 3 that

Therefore, we have . It follows from Chebyshev inequality that . Furthermore, we obtain

□

Lemma A4.

Suppose that Assumptions 1–3 hold, the row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value for sufficiently large n.

Proof of Lemma A4.

Noting that , where . To prove the row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value, we only need to prove the row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value. By the Lemma 2 in Opsomer [26], we obtain that

Thus,

It follows Lemma A1 and the definition of that the row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value. Therefore, the row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value. Furthermore, the row and column sums of are uniformly bounded in absolute value. □

Proof of Theorem 1.

By the definition of , we have

It follows from Taylor expansion of at z that

Let , we can write

and hence

where . Because

It’s easy to know that

Similarly, . It follows from Lemma A2 that

Furthermore, we have

and

Therefore, we obtain

Combing with Assumption 4, we get

Let , using Assumption 1, Assumption 2 and Lemma A1, we can show that

Thus, according to Assumption 4, we have

Denote , we obtain

□

Proof of Theorem 2.

Similarly to the proof of Theorem 2 in Kelejian and Prucha [12], we only need to prove . Write

Thus

According to Lemma A3, we get

Therefore, we have

It follows from the result in the proof of Theorem 1 that

The result then follows from Lemma 1 and the proof of Theorem 1. □

Proof of Theorem 3.

Recall that

where

Therefore, we have

To show the asymptotic normality of , it suffices to show that

First, we prove (A1). Write

When satisfies , we get

It follows by Assumption 4 and Theorem 2 that

where .

Next, we prove (A2). Write

By Assumptions 2 and 4, we have . It follows from the proof of (A1) that

Finally, we prove (A3). Write

It follows from Assumptions 1–2 that

By Assumptions 1–2, it is easy to know that

is bounded. Thus,

According to the proof of (A1), we can show that

Using results (A1)–(A3), we obtain that

□

Proof of Theorem 4.

It follows from

that

Using the result in the proof of Theorem 1, we can show that

It follows from that . By some tedious calculations, Assumption 2 and Lemma A1, we obtain

On the other hand, we have

Let , we now show that , where . By Cramér-Wold device, it suffices to show that , where is an arbitrary vector with . Clearly, . Let and , then and . Denote , write

where . To show , it is sufficient to show for arbitrary small (Davidson [29], Theorem 23.6 and Theorem 23.11). According to Assumptions 1–2, we have

where . It follows from that

By (A7) and Lemma A2, we obtain

where is the element of . It follows by expressions (A4)-(A8) that

□

Proof of Theorem 5.

Noting that

Similar to the proof of Theorem 1, we have

where , , . According to the definition of , we get

where . Combing with Lemma A4, it is easy to know that

Denote , thus . Furthermore, we get

where . Therefore, we obtain

By Theorem 2 in Opsomer and Ruppert [2] and Lemma 5 in Fan and Jiang [30], we can show that

According to the proof of Theorem 4.1 in Opsomer and Ruppert [25], we have . Combing with Assumption 4, we obtain

Let , it follows by Assumptions 1–2 and Lemma A4 that

By Assumption 6 and the proof of Theorem 1, we get

Therefore, we have

where . □

Proof of Theorem 6.

Similar to the proof of Theorem 2, it is not difficult to show that analogous statements hold for this theorem. We just need to prove . Recall that

we get

By Theorem 5 and the proof of Theorem 4.1 in Opsomer and Ruppert [25], we obtain

It follows by Assumption 2, Theorem 5 and Lemma A4 that

By Assumption 1 and Lemma A4, we have

and is bounded. It follows from Chebyshev Law of Large Number that . Therefore, we obtain

□

Proof of Theorem 7.

The reasoning for this theorem is completely analogous with Theorem 3. Noting that

where

Thus

If , then

It follows by Assumption 6 and Theorem 6 that

where .

Proof of Theorem 8.

Recall that

It follows by the proof of Theorem 7 that . Combing Assumption 2 and Lemma A4, we obtain

According to the proof of Theorem 5, noting that

Using Assumption 1 and Lemma A4, we get

By the above arguments, we have

Combing with the proof of Theorem 4.1 in Opsomer and Ruppert [25], we obtain

□

References

- Fan, J.; Gijbels, I. Local Polynomial Modelling and Its Applications; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1996; pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Opsomer, J.D.; Ruppert, D. A root-n consistent backfitting estimator for semiparametric additive modeling. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1999, 8, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzan, S.; Zerom, D. Kernel estimation of a partially linear additive model. Stat. Probabil. Lett. 2005, 72, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jiang, R.; Qiao, W. Variable selection for additive partially linear models with measurement error. Metrika 2011, 74, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Luo, Y.; Wu, X. Empirical likelihood for partially linear additive errors–in–variables models. Stat. Pap. 2012, 53, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, T. Quantile regression estimation of partially linear additive models. J. Nonparametr. Stat. 2014, 26, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Bien, J.; Caruana, R.; Gehrke, J. Sparse partially linear additive models. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2016, 25, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Härdle, W.K.; Zhang, G. Statistical inference for generalized additive partially linear models. J. Multivar. Anal. 2017, 162, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manghi, R.F.; Cysneiros, F.J.A.; Paula, G.A. Generalized additive partial linear models for analyzing correlated data. Comput. Stat. Data. An. 2019, 129, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Mei, C. Statistical inference on the parametric component in partially linear spatial autoregressive models. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2016, 45, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kelejian, H.H.; Prucha, I.R. A generalized spatial two-stage least squares procedure for estimation a spatial autoregressive model with autoregressive disturbances. J. Real. Estate. Financ. Econ. 1998, 17, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Spatial Econometrics from Cross-Sectional Data to Spatial Panels; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Jin, S. Profile quasi-maximum likelihood estimation of partially linear spatial autoregressive models. J. Econom. 2010, 157, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L. Semiparametric GMM estimation of spatial autoregressive models. J. Econom. 2012, 167, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Estimation of single-index model with spatial interaction. Reg. Sci. Urban. Econ. 2017, 62, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, X. GMM estimation of partially linear single-index spatial autoregressive model. Spat. Stat. 2019, 31, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Sun, Y. Heteroskedasticity-robust semi-parametric GMM estimation of a spatial model with space-varying coefficients. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2017, 12, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Li, S.; Tian, M. Quantile Regression for Partially Linear Varying Coefficient Spatial Autoregressive Models. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1608.01739.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2016).

- Du, J.; Sun, X.; Cao, R.; Zhang, Z. Statistical inference for partially linear additive spatial autoregressive models. Spat. Stat. 2018, 25, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Carroll, R.J. Nonparametric function estimation for clustered data when the predictor is measured without/with error. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2000, 95, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, A.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Linear smoothers and additive models. Ann. Stat. 1989, 17, 453–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härdle, W.; Hall, P. On the backfitting algorithm for additive regression models. Stat. Neerl. 1993, 47, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.J.; Tibshirani, R.J. Generalized Additive Models; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1990; pp. 136–167. [Google Scholar]

- Opsomer, J.D.; Ruppert, D. Fitting a bivariate additive model by local polynomial regression. Ann. Stat. 1997, 25, 186–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opsomer, J.D. Asymptotic properties of backfitting estimators. J. Multivar. Anal. 2000, 73, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wu, Y. Semiparametric estimation of covariance matrices for longitudinal data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2008, 103, 1520–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.H.; Cheng, G.; Liu, Y. Linear or nonlinear? Automatic structure discovery for partially linear models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2011, 106, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J. Stochastic Limit Theory: An Introduction for Econometricians; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Jiang, J. Nonparametric inferences for additive models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2005, 100, 890–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).