Patients’ Prioritization on Surgical Waiting Lists: A Decision Support System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

2.1. Waiting Lists: The Gap between Demand and Supply of Health Care

2.2. Strategies for Patients’ Prioritization

2.3. Importance of Biopsychosocial Variables

2.4. Prioritization Systems in Chile: Recent Evidence

2.5. Justification of the Chosen Method

- The international evidence shows the clinical and social importance of incorporating methodologies for the prioritization of waiting lists, with the objective of adequately responding to the clinical needs of the population. However, in Chile, there are few examples in this area, demonstrating the urgency for developing and implementing prioritization tools (in the particular case of this proposal, for waiting lists of elective interventions).

- One of the elements that transversely appears in international evidence is the need of defining, weighting and adjusting the prioritization criteria according to the clinical conditions, demographic characteristics of the patients, and social context of the region where the tool is implemented.

3. A Decision Support System for Biopsychosocial-Based Prioritization of Patients: Novel Methodological Features

3.1. Waiting List Management: National and Institutional Context

3.2. Collecting Psychosocial and Clinical Data: An Ad-Hoc Medical Record Form

3.3. Clinical and Psychosocial Characterization of Patients: Biopsychosocial Variables

3.3.1. Clinical Status of the Patients: Clinical Variables

- Progression and severity of the disease (Sever): This variable is associated with problems the disease generates and its progression, such as; hearing loss, recurrent tonsillitis, balance alterations, smell disorders, severe disorders of the voice and swallowing, head and neck tumors, among other severities. Some authors classify the severity of the disease as the most critical variable [9,24,27,42,43,44,45]. For [11] and its hierarchical system to prioritize orthopedic surgery patients, the severity of the disease has as subfactors; (i) pain and (ii) difficulty in carrying out activities. In our study, the value that Sever can take are “low”, “medium” and “high”, according to hearing loss, recurrent tonsillitis, balance disorders, among others.

- Urgency (Urg):This variable indicates the level of urgency of each patient admitted to the surgical waiting list possesses. All this according to the clinical characteristics and the psychosocial factors associated with each patient [27,44]. Urg takes values between 0 and 100, where 0 represents a patient who did not show urgency and 100 to a patient who could present the highest level of urgency. We classify as 0 the level of urgency 0, 1 the level of urgency 10, 2 the level of urgency 20, and so on until classifying the level of urgency 100 as 10.

- Clinical judgment maximum wait time (Jclin): The variable Jclin indicates the maximum time (measured in months) that the patients should wait to solve their surgical problem [26,46]. In [11] they cite a delay relation indicator (DR), which is composed of the time the patient has been waiting on the waiting list and the maximum time that the patient should wait (according to the physician’s criteria).

- Sleep disorder (Tsuen): This variable is associated with the sleep disorder problem that can be complex for some patients, as it can generate other diseases [47], such as sleep apnea syndrome [48]. Some medical specialties, such as otorhinolaryngology, have worried about the consequences this variable can have on the patients’ health [49]. In our work, the value that Tsuen can take are “low”, “medium” and “severe”.

- Probability of improvement with surgery (Pmcx): With the variable Pmcx we refer to the probability of improving the functionality, pain, general progress or other characteristics related to the patient’s illness waiting [24]. If we focus on the future benefits of the surgically treated patient, they reveal the importance of this variable within the criteria of prioritization of surgery [9,27,42,45,50,51,52,53]. The physician indicates for each patient if the probability of improving with surgery is “low”, “medium” or “high”.

- Probability of developing comorbidities without surgery (Com): The variable Com is considered as a result of waiting, where patients can develop comorbidities. Some authors incorporated it to the development of the capacities within the study of prioritization of the patients in the waiting list [24,44,51,54,55,56]. In our work, physicians indicate if patients, according to wait, developing comorbidities without surgery with probability “low”, “medium” or “high”.

- Affected area (Hanor): On clinical examination, physicians may find abnormal findings that increase the clinical complexity of the patient. According to the possible findings, the values that Hanor parameter can take are “no presence", “low presence" and “high presence".

- Diagnosis of admission to the waiting list (Diag): The Diag variable indicates the diagnosis that caused the admission of the patient to the surgical waiting list. The physicians that participated in this project grouped all the potential pathologies into 18 diagnoses.These 18 diagnoses are listed in Table 2. Additionally, we also report in this table how frequent these diagnoses are presented among the 205 patients admitted to the waiting list during the design phase.

- Other additional pathologies (Opat): The variable Opat identifies the number of additional pathologies that suffer the patients addmitted to the waiting list (besides the diagnosis that caused her/him to be admitted into the waiting list). Variable Opat associates five categories; 0 if the patient presents none of the pathologies from the list, I if the presents 1 pathology, II if the presents 2 pathologies, III if presents 3 pathologies, and IV if presents 4 or more pathologies.In Table 3 we report the list of the additional pathologies that are more likely to suffer the patients treated in the otorhinolaryngology unit.

- Other functional limitations (Olim): The Olim variable refers to difficulties directly associated with the patient’s disease in waiting. The problems stand out for; breathe, eat, drink liquids, perform sports, recreational activities or hobbies, among others. The value that Olim can take are “no”, “medium” and “severe”.

- EVA scale pain (Dolor): As cited by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience related to an existing or potential tissue injury of each individual [57].

- Need for critical beds (Ccrit): The Ccrit variable is used to indicate if a patient requires a critical bed. For this and when the patient enters the surgical waiting list, the physician must indicate “yes” or “no”, depending on the patient’s conditions.

3.3.2. Pyschosocial Status of the Patients: Psychosocial Variables

- Time on the surgical waiting list (Tlist): We use the Tlist variable to quantify the time the patient has been on the waiting list (e.g., days, weeks, months or years). This is the critical variable that patients consider and emphasize when they have a health problem, which is considered as a management variable in [9,24,44,46,50,52,58].

- Study capacity (Dest): The Dest variable is used to identify those patients, admitted to the waiting list, that suffer from difficulties for continuing their studies due to their clinical condition. This variable is only valid for patients pursuing formal studies, and it can take values “yes” or “no”.

- Family activities (Lfam): The Lfam variable is used to indicate if the patient on the waiting list has difficulties for performing domestic and family activities. For this, the pshysician indicates “yes” or “no”. The limitation of family activities has been considered in the following studies [9,24,44,45,50,52,53,59,60,61,62].

- Responsibility in caring for another person (Rcuid): The Rcuid variable indicates if the patient, despite being on the surgical waiting list, has the responsibility of caring for another person. Hence, RCuid with a “yes”, if the patient has the responsibility of caring for another person and “no” in another case. Some authors identify this variable from a psychosocial point of view [9,11,27,45,53,61].

- Working capacity (Dtrab): The variable Dtrab measures the patient’s working condition by indicating “yes” or “no”. This criterion does not apply to students or retirees. Some works have defined this variable as necessary for an adequate prioritization process since many patients face a social reality, which forces them to work. This is how [9,24,26,27,44,45,52,53,61,66] have established that the diminished working condition should be considered for patients awaiting surgery.

- Access (Acc): Given the conditions of rurality present in the Region of Maule [67], where the Hospital of Talca is inserted, it is essential to consider the condition of rurality of patients to assess to centers of public health to solve their surgical problems. The values that Acc variable can take are “urban”, “rural” and “high rurality”.

- Difficulty in transferring from/to the hospital (Dtras): The Dtras variable indicates if a patient, given their psychosocial condition, has difficulty moving to and from the hospital. For this work, the Dtras variable takes values “yes” or “no”.

3.4. Clinical and Social Characterization of Patients: Biopsychosocial Scoring, Vulnerability and Dynamic Scoring

3.4.1. Biopsychosocial Scoring Function

3.4.2. Dynamic Scoring and Vulnerability

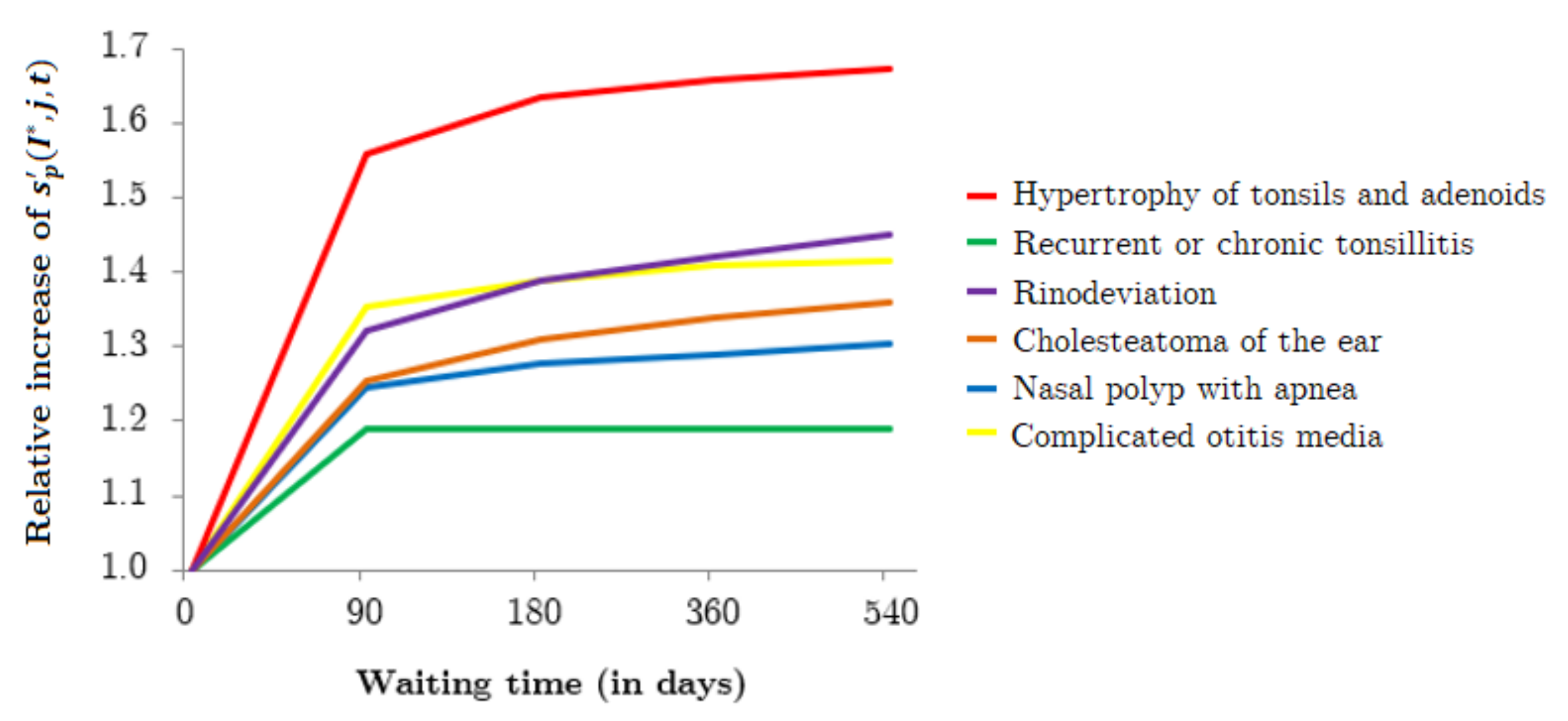

- For a given diagnoses j and a given time interval h ( corresponds to 0–90 days, to 90–180 days, to 180–360 days, and to 360–540 days), the team of physicians agreed upon a worsening factor for each time-dependent variable . This factor represents by how much the variable worsens during the interval h.These intervals and worsening factors were defined by team of physicians, based on clinical records and their clinical experience. Two validation meeting were convened for agreeing upon the final values. Physicians considered up to 540 days in the waiting list as any patient that reaches that waiting time is immediately scheduled for surgery, regardless of her/his condition.

- Let be the value associated to variable for a given patient p on the k-th day of the time interval h; this value is given bywhere corresponds to the number of days of time interval h. For ease of notation, we assume that corresponds to moment that the patient is admitted to the waiting list, that is, and, therefore, , for all patients p and variables .

- Finally, considering the previous definition, we get that after t days in the waiting list, the value of time-dependent biopsychosocial variable associated to patient p, whose main diagnosis is j, is given by

3.5. Selecting Prioritized Patients for Surgery Scheduling

- For each patient p in the waiting list, update the values of and , considering that t is associated to the end of the scheduling horizon of seven days. Let be the average value of among all patients.

- Classify patients into four groups: Group 1: patients with and ; Group 2: patients with and ; Group 3: patients with and ; and Group 4: patients with and (see the four quadrants in Figure 2).

- Classify patients into three groups: Group A: patients suffering from diagnosis of Type A; Group B: patients suffering from diagnosis of Type B; and Group C: patients suffering from diagnosis of Type C (see the three colors in which patients are represented in Figure 2).

- Schedule as many surgeries as possible for patients from Group 1 and Group A in the available operating-room time slots; if operating-room time slots are still available, then schedule as many surgeries as possible for patients from Group 1 and Group B; and if operating-room time slots are still available, then schedule as many surgeries for patients from Group 1 and Group C as possible.

- If all patients of Group 1 are selected and there are still operating-room time slots; repeat the previous procedure for patients from Group 2, 3 and 4, consecutively.

4. Results and Comparison with Previous Prioritization Method

4.1. Average Number of Days Waiting for Surgery

4.2. Qualitative Evaluation of the Prioritization Method

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- 1.

- Sever. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Sever category of patient p is “low”, when the category is “medium”, and when the category is “high”.

- 2.

- Urg. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Urg category of patient p is “0”, when the category is “1”, when the category is “2”, when the category is “3”, when the category is “4”, when the category is “5”, when the category is “6”, when the category is “7”, when the category is “8”, when the category is “9”, and when the category is “10”.

- 3.

- Jclin. The physician indicates the maximum waiting time the patient should wait, in months. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Jclin category of patient p is “I”, when the category is “II”, when the category is “III”, when the category is “IV”, when the category is “V”, when the category is “VI”, when the category is “VII”, when the category is “VIII”, when the category is “IX”, and when the category is “X”.

- 4.

- Tsuen. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Tsuen category of patient p is “low”, when the category is “medium”, and when the category is “severe”.

- 5.

- Tlist. Corresponds to the time the patient p has been on hold, in months. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Tlist category of patient p is "0–3”, when the category is “4–6”, when the category is “7–9”, when the category is “10–12”, when the category is “13–18”, when the category is “19–24”, when the category is “25–36”, when the category is “37–48”, when the category is “49–60”, and when the category is “+60”.

- 6.

- Pmcx. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Pmcx category of patient p is “low”, when the category is “medium”, and when the category is “high”.

- 7.

- Dest. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Dest category of patient p is “NA”, when the category is “yes”, and when the category is “no”.

- 8.

- Com. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Com category of patient p is “low”, when the category is “medium”, and when the category is “high”.

- 9.

- Lfam. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Lfam category of patient p is “yes”, and when the category is “no”.

- 10.

- Hanor. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Hanor category of patient p is “no presence”, when the category is “low presence”, and when the category is “high presence”.

- 11.

- Opat. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Opat category of patient p is “0” additional pathologies, when the category is “I”, when the category is “II”, when the category is “III”, and when the category is “IV”.

- 12.

- Diag. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Diag diagnosis of patient p is “complicated otitis media”, when the diagnosis is “cholesteatoma of the ear”, when the diagnosis is “complicated chronic sinusitis”, when the diagnosis is “obstructive tonsil and apnea”, when the diagnosis is “otitis media with effusion”, when the diagnosis is “nasal polyp with apnea”, when the diagnosis is “obstructive sleep apnea”, when the diagnosis is “obstructed lacrimal obstruction”, when the diagnosis is “frontal mucocele”, when the diagnosis is “septodesk with apnea”, when the diagnosis is “simple chronic sinusitis”, when the diagnosis is “hypertrophy of tonsils and adenoids”, when the diagnosis is “recurrent or chronic tonsillitis”, when the diagnosis is “tympanic perforation”, when the diagnosis is “nasal polyp without apnea”, when the diagnosis is “tear ducts obstruction”, when the diagnosis is “septo-deviation without apnea”, and when the diagnosis is “rinodeviation”.

- 13.

- Olim. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Olim category of patient p is “no”, when the category is “medium”, and when the category is “severe”.

- 14.

- Ncuid. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Ncuid category of patient p is “yes”, and when the category is “no”.

- 15.

- Rcuid. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Rcuid category of patient p is “yes”, and when the category is “no”.

- 16.

- Dolor. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Dolor category of patient p is “0”, when the category is “1”, when the category is “2”, when the category is “3”, when the category is “4”, when the category is “5”, when the category is “6”, when the category is “7”, when the category is “8”, when the category is “9”, and when the category is “10”.

- 17.

- Dtrab. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Dtrab category of patient p is “NA”, when the category is “yes”, and when the category is “no”.

- 18.

- Acc. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Acc category of patient p is “urban”, when the category is “rural”, and when the category is “high rurality”.

- 19.

- Dtras. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Dtras category of patient p is “yes”, and when the category is “no”.

- 20.

- Ccrit. For a given patient p, the corresponding value corresponds to when the Ccrit category of patient p is “yes”, and when the category is “no”.

Appendix C

References

- Jiang, S.; Chin, K.; Wang, L.; Qu, G.; Tsui, K. Modified genetic algorithm-based feature selection combined with pre-trained deep neural network for demand forecasting in outpatient department. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 82, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J. Waiting list behaviour and the consequences for NHS targets. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2010, 61, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, J.; Crump, R.; Chan, A.; Liu, G.; Yue, E.; Bair, M. Health of patients on the waiting list: Opportunity to improve health in Canada? Health Policy 2016, 120, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilkhuysen, G.; Oudhoff, J.; Rietberg, M.; Van der Wal, G.; Timmermans, D. Waiting for elective surgery: A qualitative analysis and conceptual framework of the consequences of delay. Public Health 2005, 119, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutacker, N.; Siciliani, L.; Cookson, R. Waiting time prioritisation: Evidence from England. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 159, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, E.; Okudan, G.; Ashour, O. Rank aggregation methods comparison: A case for triage prioritization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riff, M.; Cares, J.; Neveu, B. RASON: A new approach to the scheduling radiotherapy problem that considers the current waiting times. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 64, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, F.; Cohen, R.; Mingrone, G.; le Roux, C.; Mechanick, J.; Arterburn, D.; Vidal, J.; Alberti, G.; Amiel, S.; Batterham, R.; et al. Bariatric and metabolic surgery during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: DSS recommendations for management of surgical candidates and postoperative patients and prioritisation of access to surgery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allepuz, A.; Espallargues, M.; Martínez, O. Criterios para priorizar a pacientes en lista de espera para procedimientos quirúrgicos en el Sistema Nacional de Salud. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2009, 24, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, A.; Appleby, J. English NHS waiting times: What next? J. R. Soc. Med. 2009, 102, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Jamshidi, A.; Ruiz, A.; Aït-Kadi, D. A new dynamic integrated framework for surgical patients’ prioritization considering risks and uncertainties. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 88, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Barquero, J.; Martín-Vegue, A.; Castanedo, S.; Discapacidades, G.C. La familia internacional de clasificaciones de la OMS (FIC-OMS): Una nueva visión. Pap Med. 2001, 10, 184–187. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.; Obando, L. La discapacidad, una mirada desde la teoría de sistemas y el modelo biopsicosocial. Rev. Hacia la Promoción de la Salud 2007, 12, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, D.; Chamblas, I.; Zavala, M.; Müller, R.; Rodríguez, M.; Chávez, A. Determinantes sociales en salud y estilos de vida en población adulta de Concepción, Chile. Ciencia Enfermería 2014, 20, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. J. Med. Philos. A Forum Bioeth. Philos. Med. 1981, 6, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, P. Prioritising waiting lists: How and why? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2003, 150, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliani, L.; Hurst, J. Tackling excessive waiting times for elective surgery: A comparative analysis of policies in 12 OECD countries. Health Policy 2005, 72, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliani, L.; Moran, V.; Borowitz, M. Measuring and comparing health care waiting times in OECD countries. Health Policy 2014, 118, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, M.; Besoaín, Á.; Rebolledo, J. Determinantes sociales de la salud y discapacidad: Actualizando el modelo de determinación. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, R.; Testi, A.; Tanfani, E.; Fato, M.; Porro, I.; Santo, M.; Santori, G.; Torre, G.; Ansaldo, G. A model to prioritize access to elective surgery on the basis of clinical urgency and waiting time. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Bishay, H.; Bastien, G.; Peng, B.; Phillips, R. Configuring policies in public health applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 32, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netten, A.; Curtis, L. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care; Canterbury University: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Testi, A.; Tanfani, E.; Valente, R.; Ansaldo, G.; Torre, G. Prioritizing surgical waiting lists. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2008, 14, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solans-Domènech, M.; Adam, P.; Tebé, C.; Espallargues, M. Developing a universal tool for the prioritization of patients waiting for elective surgery. Health Policy 2013, 113, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.; Menaker, R. Waiting for children’s surgery in Canada: The Canadian Paediatric Surgical Wait Times project. CMAJ 2011, 183, E559–E564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudhoff, J.; Timmermans, D.; Rietberg, M.; Knol, D.; van der Wal, G. The acceptability of waiting times for elective general surgery and the appropriateness of prioritising patients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadorn, D.; Steering Committee of the Western Canada Waiting List Project. Setting priorities for waiting lists: Defining our terms. CMAJ 2000, 163, 857–860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.; Hadorn, D.; Steering Committee of the Western Canada Waiting List Project. Developing priority criteria for general surgery: Results from the Western Canada Waiting List Project. Can. J. Surg. 2002, 45, 351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Conner-Spady, B.; Arnett, G.; McGurran, J.; Noseworthy, T.; Steering Committee of the Western Canada Waiting List Project. Prioritization of patients on scheduled waiting lists: Validation of a scoring system for hip and knee arthroplasty. Can. J. Surg. 2004, 47, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Abásolo, I.; Barber, P.; López-Valcárcel, B.; Jiménez, O. Real waiting times for surgery. Proposal for an improved system for their management. Gac. Sanit. 2014, 28, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Jamshidi, A.; Ruiz, A.; Aït-Kadi, D. Multi-criteria decision making approaches to prioritize surgical patients. In Health Care Systems Engineering for Scientists and Practitioners; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Petwal, H.; Rani, R. Prioritizing the Surgical Waiting List-Cosine Consistency Index: An Optimized Framework for Prioritizing Surgical Waiting List. J. Med. Imaging Health Inform. 2020, 10, 2876–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, J.; Noel, C.; Forner, D.; Zhang, H.; Nichols, A.; Cohen, M.; Wong, R.; McMullen, C.; Graboyes, E.; Divi, V.; et al. Development and validation of a Surgical Prioritization and Ranking Tool and Navigation Aid for Head and Neck Cancer (SPARTAN-HN) in a scarce resource setting: Response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer 2020, 126, 4895–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, S.; Dery, J.; Lamontagne, M.; Jamshidi, A.; Lacroix, E.; Ruiz, A.; Ait-Kadi, D.; Routhier, F. Prioritization of patients access to outpatient augmentative and alternative communication services in Quebec: A decision tool. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.; Engel, L. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am. J. Psychiatry 1980, 137, 535–544. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell-Carrió, F.; Suchman, A.; Epstein, R. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: Principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.; Olden, K.; Naliboff, B.; Bradley, L.; Francisconi, C.; Drossman, D.A.; Creed, F. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seery, M. The biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat: Using the heart to measure the mind. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2013, 7, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.; Halligan, P. The biopsychosocial model of illness: A model whose time has come. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, M. Priorización de listas de espera de cirugía para la gestión de pabellones quirúrgicos del Hospital Pediátrico Dr. Exequiel González Cortés. Master’s Thesis, Industrial Engineering Department, School of Engineering, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Julio, C.; Wolff, P.; Yarza, M. Modelo de gestión de listas de espera centrado en oportunidad y justicia. Rev. Médica Chile 2016, 144, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennett, E.; Kipping, R.; Parry, B.; Windsor, J. Priority access criteria for elective cholecystectomy: A comparison of three scoring methods. N. Z. Med. J. 1998, 111, 231–233. [Google Scholar]

- Derrett, S.; Devlin, N.; Hansen, P.; Herbison, P. Prioritizing patients for elective surgery: A prospective study of clinical priority assessment criteria in New Zealand. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2003, 19, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCormick, A.; Collecutt, W.; Parry, B. Prioritizing patients for elective surgery: A systematic review. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampietro-Colom, L.; Espallargues, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Comas, M.; Alonso, J.; Castells, X.; Pinto, J. Wide social participation in prioritizing patients on waiting lists for joint replacement: A conjoint analysis. Med. Decis. Mak. 2008, 28, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, B.; Esmail, N. Waiting Your Turn: Wait Times for Health Care in Canada; Technical Report, Studies in Health Policy; Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pack, A.; Pien, G. Update on sleep and its disorders. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schredl, M. Dreams in patients with sleep disorders. Sleep Med. Rev. 2009, 13, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, H.; Altevogt, B. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Míguez, E.; Herrero, C.; Pinto-Prades, J. Using a point system in the management of waiting lists: The case of cataracts. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCormick, A.; Macmillan, A.; Parry, B. Identification of criteria for the prioritisation of patients for elective general surgery. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2004, 9, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inza, F.; Iriso, E.; Hita, J. Instrumentos económicos para la priorización de pacientes en lista de espera: La aplicación de modelos de elección discreta. Gac. Sanit. 2008, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, P.; Alomar, S.; Espallargues, M.; Herdman, M.; Sanz, L. Priorització de Pacients en Llista D’espera per a Cirurgia Electiva de Raquis o Fusió Vertebral; Technical Report; L’Agència d’Informació, Avaluació i Qualitat en Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Salut: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Western Canada Waiting List (WCWL) Project. From Chaos to Order: Making Sense of Waiting Lists in Canada; WCWL Project, University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, V.; Lai, T.; Lam, P.; Lam, D. Prioritization of cataract surgery: Visual analogue scale versus scoring system. ANZ J. Surg. 2005, 75, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A.; Quintana, J.; Espallargues, M.; Allepuz, A.; Ibañez, B. Different hip and knee priority score systems: Are they good for the same thing? J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prades, J.; Gavid, M. Dolor en otorrinolaringología. EMC-Otorrinolaringología 2018, 47, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalan Agency for Health Information. Priority-Setting for Elective Surgery Procedures with Waiting Lists of the Public Healthcare System of Catalonia. 2011. Available online: https://aquas.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/aquas/publicacions/2010/pdf/priority_waitinglist_catalonia_cahiaq2010en.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Hadorn, D. Developing priority criteria for magnetic resonance imaging: Results from the Western Canada Waiting List Project. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2002, 53, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Lundström, M.; Albrecht, S.; Håkansson, I.; Lorefors, R.; Ohlsson, S.; Polland, W.; Schmid, A.; Svensson, G.; Wendel, E. NIKE: A new clinical tool for establishing levels of indications for cataract surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2006, 84, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, J.; Scott, A.; Osborne, R. Designing choice experiments with many attributes. An application to setting priorities for orthopaedic waiting lists. Health Econ. 2009, 18, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Las Hayas, C.; González, N.; Aguirre, U.; Blasco, J.; Elizalde, B.; Perea, E.; Escobar, A.; Navarro, G.; Castells, X.; Quintana, J.; et al. Can an appropriateness evaluation tool be used to prioritize patients on a waiting list for cataract extraction? Health Policy 2010, 95, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, E.; Dos Santos, R., Jr.; Miyazaki, M.; Domingos, N.; Felicio, H.; Rocha, M.; Arroyo, P., Jr.; Duca, W.; Silva, R.; Silva, R. Patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation: Caregiver burden and stress. Liver Transplant. 2010, 16, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papastavrou, E.; Kalokerinou, A.; Papacostas, S.; Tsangari, H.; Sourtzi, P. Caring for a relative with dementia: Family caregiver burden. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 58, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etters, L.; Goodall, D.; Harrison, B. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2008, 20, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudhoff, J.; Timmermans, D.; Knol, D.; Bijnen, A.; Van der Wal, G. Prioritising patients on surgical waiting lists: A conjoint analysis study on the priority judgements of patients, surgeons, occupational physicians, and general practitioners. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 1863–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Compendio Estadístico 2015 INE (Chile); Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Santiago, Chile, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Tan, E.; Zhou, F.; Lei, B. Joint detection and clinical score prediction in Parkinson’s disease via multi-modal sparse learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 80, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characterization of the 205 Patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | n | Gender | n | Type of Patient | n | Other Pathologies | n |

| 0–20 | 126 | Male | 100 | New | 38 | 0 | 150 |

| 21–40 | 25 | Female | 150 | Treated | 167 | 1 | 38 |

| 41–60 | 32 | 2 | 13 | ||||

| +60 | 22 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| +3 | 1 | ||||||

| Diagnoses | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| Complicated otitis media | 10 |

| Cholesteatoma of the ear | 6 |

| Complicated chronic sinusitis | 4 |

| Obstructive tonsil and apnea | 13 |

| Otitis media with effusion | 1 |

| Nasal polyp with apnea | 3 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 0 |

| Obstructed lacrimal obstruction | 3 |

| Frontal mucocele | 1 |

| Septodesk with apnea | 1 |

| Simple chronic sinusitis | 1 |

| Hypertrophy of tonsils and adenoids | 78 |

| Recurrent or chronic tonsillitis | 31 |

| Tympanic perforation | 21 |

| Nasal polyp without apnea | 4 |

| Tear ducts obstruction | 7 |

| Septo-deviation without apnea | 17 |

| Rinodeviation | 4 |

| Additional Pathologies |

|---|

| Bronchial asthma |

| Immunosuppressed |

| Risk of malignancy |

| Sleep apnea syndrome |

| Diabetes |

| Language disorder |

| Valvulopathy |

| Arterial hypertension |

| Rheumatic arthritis |

| Risk of complications |

| Hearing loss |

| Neurological complications |

| Infectious complications |

| Depression |

| Chronic lung disease |

| Nutritional diseases |

| Down’s Syndrome |

| Gastrointestinal disorders |

| m | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Definition | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Sever (*) | Severity | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0.081 |

| Urg (*) | Urgency | 8 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 0.076 |

| Jclin | Maximum waiting time | 3 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 0.066 |

| Tsuen (*) | Sleep disorder | 6 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 0.063 |

| Tlist | Time on list | 7 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 0.062 |

| Pmcx (*) | Expected improvement due to surgery | 1 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 0.055 |

| Dest (*) | Capacity to study | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 0.054 |

| Com (*) | Chances of developing comorbidities | 1 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 0.053 |

| Lfam (*) | Capacity of participating in family activities | 5 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 0.053 |

| Hanor (*) | Affected area | 2 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 0.052 |

| Opat | Presence of other pathologies | 2 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 0.047 |

| Diag | Diagnosis | 2 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 0.046 |

| Olim (*) | Other limitations | 2 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 0.045 |

| Ncuid | Need of a caregiver | 5 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 0.043 |

| Rcuid | Patient cares for another person | 5 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0.043 |

| Dolor (*) | Pain scale | 1 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 0.040 |

| Dtrab | Capacity to work | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.038 |

| Acc | Type of residence area | 5 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 0.033 |

| Dtras | Difficulty in transfering | 5 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0.028 |

| Ccrit | Need for clinical bed | 1 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.023 |

| 1.0 | |||||||||

| t | rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 31.08.2018 | 3.830 | 0 | 78 |

| 30.11.2018 | 4.519 | 0.5 | 43 |

| 28.02.2019 | 4.519 | 1 | 18 |

| 31.05.2019 | 4.519 | 1.5 | 15 |

| 31.08.2019 | 4.519 | 2 | 10 |

| 01.10.2019 | 4.519 | 2.17 | 6 |

| n | ||

|---|---|---|

| 31.12.2015 | 998 | 419 |

| 31.12.2016 | 1200 | 470 |

| 31.12.2017 | 1123 | 496 |

| 31.12.2018 | 1108 | 281 |

| 31.12.2019 | 1307 | 282 |

| Qualitative Atributes | Previous Method | Proposed Method |

|---|---|---|

| Prioritization | Subjective | Greater objectivity |

| Profile discrimination | Manual observation | System observation |

| Timely selection | Rarely | Frequently |

| Equitable | Sometimes | Always |

| Physician satisfaction | Low | High |

| Side effects due to the waiting time | High | Medium |

| Presurgical process | Same | Improvement |

| See all patients orderer | No | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva-Aravena, F.; Álvarez-Miranda, E.; Astudillo, C.A.; González-Martínez, L.; Ledezma, J.G. Patients’ Prioritization on Surgical Waiting Lists: A Decision Support System. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101097

Silva-Aravena F, Álvarez-Miranda E, Astudillo CA, González-Martínez L, Ledezma JG. Patients’ Prioritization on Surgical Waiting Lists: A Decision Support System. Mathematics. 2021; 9(10):1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101097

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva-Aravena, Fabián, Eduardo Álvarez-Miranda, César A. Astudillo, Luis González-Martínez, and José G. Ledezma. 2021. "Patients’ Prioritization on Surgical Waiting Lists: A Decision Support System" Mathematics 9, no. 10: 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101097

APA StyleSilva-Aravena, F., Álvarez-Miranda, E., Astudillo, C. A., González-Martínez, L., & Ledezma, J. G. (2021). Patients’ Prioritization on Surgical Waiting Lists: A Decision Support System. Mathematics, 9(10), 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9101097