Abstract

Variable Mesh Optimization with Niching (VMO-N) is a framework for multimodal problems (those with multiple optima at several search subspaces). Its only two instances are restricted though. Being a potent multimodal optimizer, the Hill-Valley Evolutionary Algorithm (HillVallEA) uses large populations that prolong its execution. This study strives to revise VMO-N, to contrast it with related approaches, to instantiate it effectively, to get HillVallEA faster, and to indicate methods (previous or new) for practical use. We hypothesize that extra pre-niching search in HillVallEA may reduce the overall population, and that if such a diminution is substantial, it runs more rapidly but effective. After refining VMO-N, we bring out a new case of it, dubbed Hill-Valley-Clustering-based VMO (HVcMO), which also extends HillVallEA. Results show it as the first competitive variant of VMO-N, also on top of the VMO-based niching strategies. Regarding the number of optima found, HVcMO performs statistically similar to the last HillVallEA version. However, it comes with a pivotal benefit for HillVallEA: a severe reduction of the population, which leads to an estimated drastic speed-up when the volume of the search space is in a certain range.

1. Introduction

In the arena of optimization, a heuristic algorithm seeks for solutions that are good enough (not necessarily optimal) within a fair computation time [1]. Thus, it is crucial to keep the balance between the quality of the approximated solutions and the time used to reach them. Beyond simple heuristics for specific problems, metaheuristics are intelligent mechanisms that guide other heuristics through the search process [2]. Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) are a category of metaheuristics based on biological evolution. As global optimization methods, typical single objective EAs seek for a unique global optimum, ignoring the possible existence of other optima. That means a serious limitation in industrial scenarios described by multimodal optimization problems, such as those reported in [3,4]. In this context, the term multimodality denotes the presence of optima in various regions of the search space. Many decisions in engineering, e.g., selecting a final design, depend on the earlier optimization of relevant aspects, i.e., cost and simplicity [5]. Hence, experts look for several optima instead of the only best solution, so they can choose the most suitable by considering further practical aims.

In the course of the last four decades, researchers have steadily coped with that dilemma, leading to the resultant field of evolutionary multimodal optimization [6]. The simultaneous detection of multiple optima in the search space is a big challenge. Such a high difficulty, together with the vast range of application domains comprised, make it a very active research field that intends the devise of niching algorithms [6,7], which are the key methods here, and their coupling with metaheuristics. Inspired by the dynamics of the ecosystems in nature, the paradigm of niching is the common computational choice for multimodal optimization. Niching techniques have complemented several metaheuristic approaches, e.g., Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [5,6,7,8,9,10], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [11,12,13,14] and Differential Evolution (DE) [15,16,17,18]. Because of their strong synergy, niching methods have also been explained as the extension of EAs to multimodal scenarios [19].

The Variable Mesh Optimization (VMO) [20] metaheuristic has proved to perform competitively in continuous landscapes. In its canonical form, it is capable to locate different optimal solutions but it cannot maintain them over the time [21]. A few works [21,22,23] have augmented VMO as to make it cope with multimodality. They include VMO-N [22], a generic VMO framework for multimodal problems, whose only two instances are termed Niche-Clearing-based VMO (NC-VMO) [21] and Niche-based VMO via Adaptive Species Discovery (VMO-ASD) [22]. The experimental analysis demonstrated that VMO-N is a suitable approach for multimodal optimization. However, a final request in [22] persists as the search for a strongly competitive variant of VMO-N, which uses a more robust niching procedure than those in NC-VMO and VMO-ASD.

To annul that limitation, we unveil a new case of VMO-N that exploits the Hill-Valley Clustering (HVC) niching technique [24], and the Adapted Maximum-Likelihood Gaussian Model Iterated Density-Estimation Evolutionary Algorithm with univariate Gaussian distribution (AMaLGaM-Univariate) [25,26]. Recently, Maree et al. [24,27] successfully used those methods together in the HillVallEA scheme. Motivated by their relevant outcomes, we instantiate the VMO-N framework by incorporating such a joint strategy. The ensuing HVcMO method is expressly dubbed HVcMO20a when pointing at its primary setup. This is the first competitive version of VMO-N. To support this claim, we compared it to remarkable metaheuristic strategies for multimodal optimization. Further than the VMO-N’s instances, HVcMO20a overcomes the Niching VMO (NVMO) [23] method, as far as we know, the other VMO-based approach for multimodal optimization reported in the literature.

In addition, HVcMO is not only a case of VMO-N, but also an extension of HillVallEA19, the ultimate version of HillVallEA, a quite sophisticated metaheuristic for multimodal optimization. HillVallEA19 [27] outperforms the algorithms presented in the last two editions (2018 and 2919) of the Competition on Niching Methods for Multimodal Optimization, within the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference (GECCO) [28]. In spite of that, a strong weakness of HillVallEA19 is that it tends to need very large populations. However, it is not occasional at all that an effective multimodal optimizer suffers such a drawback, considering that many functions have a large number of optima to be found, and that many of them involve numerous variables as well.

As expected, observed results show that the combined use of HVC and AMaLGaM-Univariate within HVcMO make that VMO-oriented optimizer capable to approximate multimodal problems effectively. On the other hand, the application of the search operators of VMO allows such an extended HillVallEA mechanism to perform faster over a large set of problems among those used in this study, which derives from an overall reduction of the population size on the problem in the test suite. This fact evidences the mutual benefit of using both approaches together. Given new multimodal optimization problems, apart from those seen in this study, it is then possible to recommend either HVcMO20a or HillVallEA19 to solve such problems, according to their common characteristics with the benchmark functions approximated by these algorithms.

Multimodal optimization is theorized in Section 2, together with some niching-related concepts. Relevant works, including VMO-N and HillVallEA, are reviewed in Section 3, where some ideas to deal with outlined shortcoming are exposed as the objectives of this research. The VMO-N framework is improved in Section 4, and then instantiated as the HVcMO algorithm. Section 5 describes the setup for the experiments to validate and analyze such a new proposal, whose results are discussed in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 comes with the conclusions and some directions for future work.

2. Formal Notion of Multimodal Optimization and Niching Approach

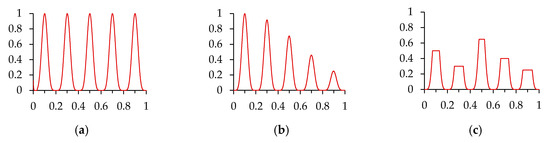

For a sake of simplicity, multimodal optimization is usually defined in informal manners, mostly by means of some descriptive cases of multimodal scenarios, like in Figure 1. Such conceptualizations are definitely valid and assure a straightforward understanding of what multimodal optimization is.

Figure 1.

Examples of multimodal maximization functions, including a couple of usual benchmarks: (a) Equal Maxima; (b) Uneven Decreasing Maxima. The last graph illustrates: (c) a case with plateaus.

However, even supported by examples of functions, a more formal viewpoint is necessary. Let us formulate a continuous optimization problem as a model driven by the elements below:

standing for a search space, an abstract construction of all the possible solutions over a finite set of decision variables , with , where is the dimension of . For each , the pair of lower () and upper () bounds (limits) of its domain is given in . Being the set of constraints between variables, is an unconstrained problem if . Finally, indicates the objective function to optimize (either minimize or maximize).

In this scenario, instantiating a variable means to assign a real value to it, that is:

and therefore, a solution is a complete assignation where the values given to the decision variables satisfy the constraints in . A solution signifies a global optimum for a minimization problem if and only if reaches its lowest value at , among all the solutions in . Contrarily, when is a maximization problem, is said a global optimum iif is the largest value of the objective function in . Those two criteria for global optimality can be defined in a formal fashion as:

Likewise, a solution may be a local optimum for , i.e., in a certain region . Since the decision variables are real-valued, the number of subsets of is infinite, and seemingly the number of local optima, but only the subspaces that represent peaks count. The set of peaks () denotes the partition of whose elements are regions where is quasi-convex, for a minimization task:

or quasi-concave, in the event of a maximization problem:

In Figure 1, each example of maximization consists of five (quasi-concave) peaks. In the rightmost graph, the peaks indeed end in ‘plateaus’, i.e., flat regions of where the infinite encircled solutions have exactly the same fitness value. Formally, the local optimality can be defined as:

While a global optimum is also a local one in the peak it belongs to, it is common to disjoint those concepts for practical reasons. Let us denote the (complete) set of local optima (i.e., one optimum per peak; infinite if a plateau), and be the set of global optima, so that . Hereinafter, by ‘local optima’ we refer only to the partial set of local optima (), which excludes the global ones:

The global optimization approach solely accepts that and . Diametrically, the multimodal optimization paradigm concerns the existence of multiple peaks (), not only several optima. For instance, a single-peak function ending in a flat region (infinite optima) is weak unimodal [29]. Solving a multimodal optimization problem means locating all peaks. The standard population-based optimizers are then modified to create stable subpopulations (known as niches) at all peaks to discover. Actually, niching algorithms exist for that purpose. Being the best solution in a niche referred as its master, every niche corresponds to a single peak of the multimodal problem, and most functions are featured by peaks of distinct radii, usually unknown. Several of those problems have been standardized as test cases for new multimodal optimizers. For some of them, the number of local optima is known precisely; in others, it is simply huge. Thus, only the global optima located are used for assessing the performance of new algorithms, which then might avoid efforts on finding local optima. It does not mean any shortage as most of those algorithms can be easily adapted to pursue global and local optima all together, when required in real-world scenarios.

3. Related Works

This section exposes key drawbacks of the multimodal optimizers. Besides, it elaborates on the basics of VMO and HillVallEA, the direct precedents of this paper. Despite VMO-N and NVMO are the two main augmented versions of VMO for multimodal scenarios, no study has addressed their conceptual differences. Such a lack directly calls for comparing them from theoretical viewpoints, which turns up as the first goal of this investigation. Some downsides of VMO-N and HillVallEA are underlined as well, together with other consequential research objectives to mitigate such limitations.

3.1. Evolutionary Multimodal Optimizers

Because of their population-based nature, standard evolutionary algorithms can locate several globally best solutions at the same time, instead of only one. There is no guarantee that they are kept in the population during the next iterations though. A simple alternative is to seed all those solutions in the population for the upcoming generation. However, it might cause some undesired effects, e.g., guiding the algorithm to previously explored regions of the search space and therefore delaying the overall search process. Another option is to ‘memorize’ the set of such globally best solutions, aside from the population. Some of them must probably belong to the same peak of the fitness landscape. Even so, by having an updated list of such fittest solutions, some looked-for optima might appear, eventually. While the literature reports several examples [18,20,24,30], every single EA may be adapted in line with that strategy, as to make it able to deal with multimodality. The efficacy of such augmented algorithms over multimodal problems will still rely on their search capability though.

On the contrary, niching methods represent the choice to turn EAs into multimodal optimizers whose success does not rely on their search abilities. By complementing them with niching methods, EAs are able to form different subpopulations and maintain them along the search process, in order to identify multiple optima together. As indicated in [21,22], in spite of the numerous works completed about multimodal optimization, it continues as a challenging research field due to various shortcomings of the niching algorithms. Certainly, their dependence on parameters that characterize the target functions, e.g., the radius of the niches, is the greatest weakness of multimodal optimizers. Furthermore, most of those optimization techniques are incapable to solve multimodal problems that have a large number of optima, which implies the necessity for more effective niching methods.

Evolutionary multimodal optimizers are also susceptible to the dimension of the problem, i.e., the number of variables involved. It is said that an optimization algorithm is scalable if it continues performing effectively when the dimension of the problem increases. Regarding this matter, Kronfeld and Zell [31] drew attention to the lack of studies about the scalability of multimodal optimization methods, a matter that remains. Other important drawbacks that have been poorly approached concern the high computational complexity of such techniques, which determines the time they need to approximate multimodal problems. This paper covers that issue, not in a generic manner but addressing only a couple of methods relevant for this investigation, namely the inspiring HillVallEA19 and our proposed extension of it, the HVcMO20a algorithm (also a case of VMO-N).

3.2. The VMO Metaheuristic

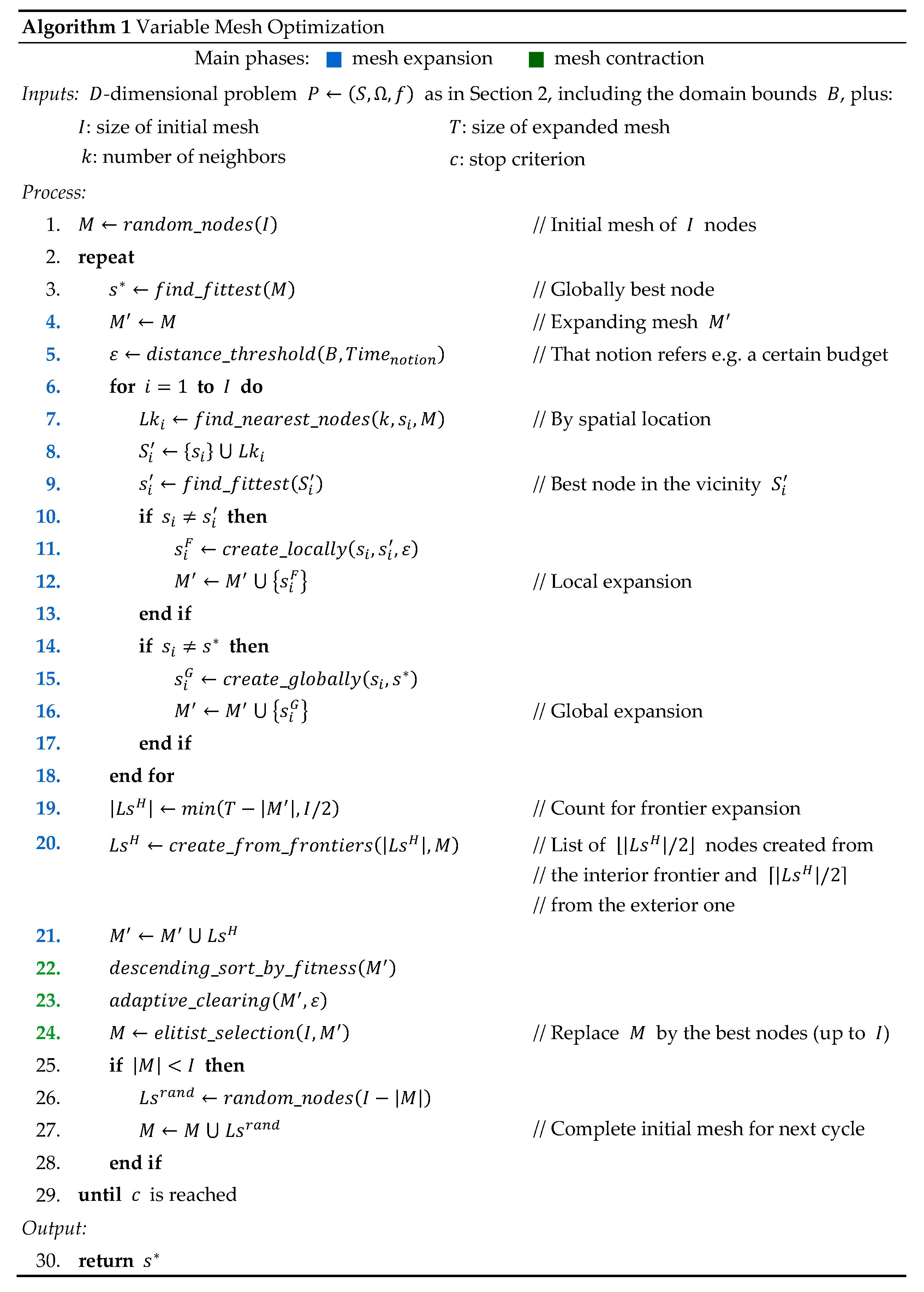

In the Variable Mesh Optimization scheme, the candidate solutions are denoted as nodes. Thus, the population is seen as a mesh that initially has I nodes . Every single node , with , is represented as a real-valued vector of dimension , i.e., . As described in Algorithm 1, the evolutionary search loop of VMO is controlled by four basic parameters, namely the size () of the initial mesh in each generation, the maximum number () of individuals in the total (expanded) mesh, the number () of nodes in the neighborhood of any given node, and the stop criterion (). Note that in this paper, every collection starts with index 1.

The search process by VMO mainly consists of two stages: the mesh expansion and the mesh contraction, set together to keep exploration and exploitation in balance. The expansion occurs by dint of the main ways of search in VMO, namely the F-operator, the G-operator and the H-operator [20]. They respectively deal with the creation of new nodes toward the local optima (Algorithm 1, line 11), headed for the global optimum (line 15), and from those nodes in the frontiers of the mesh (line 20). Once the mesh is expanded, the contraction stage runs an elitist selection of nodes in the current generation to keep them in the initial mesh of the next iteration. Such a selection is previously affected by the adaptive clearing operator.

3.3. Is the VMO’s Adaptive Clearing a Niching Method?

This technique is proved useful for VMO to deal with complex functions [32]. Despite that study concerns global optimization only, it fairly takes multimodal problems for benchmarking because of their high difficulty. When it comes to the research about VMO for multimodal optimization [21,22,23], the adaptive clearing has shown controversial though. To analyze about that, it is beneficial to have look at a certainly similar niching method, the classic clearing proposed by Petrowski [33]. Beyond the common aspects, a few relevant facts make them divergent, as the descriptions in Algorithm 2 suggest. In this context, for the sake of parity, the population handled by the Petrowski’s method is referred as , which actually occurs when it is picked as the niching idea in VMO-N, like in [21].

| Algorithm 2 Clearing methods: (a) Petrowski’s clearing; (b) VMO’s adaptive clearing | |

| Inputs: | Inputs: |

| : mesh expanded in a search space , and : set of domain bounds of the variables (Section 2) | |

| : niche radius | : an estimate of the time passed, e.g. |

| : maximum number of winners (individuals in | the budget used (given maximum number |

| any single niche) | of either iterations or fitness evaluations) |

| Process: | Process: |

| 1. | 1. |

| 2. | 2. |

| 3.for to do | 3.for to do |

| 4. if then | 4. for to do |

| 5. | 5. if then |

| 6. | 6. |

| 7. | 7. |

| 8. for to do | 8. end if |

| 9. if and | 9. end for |

| then | |

| 10. if then | |

| 11. | |

| 12. | |

| 13. else | |

| 14. | |

| 15. end if | |

| 16. end if | |

| 17. end for | |

| 18. | |

| 19. end if | |

| 20.end for | |

| Output: | Output: |

| 21.return | 10.return |

| (a) | (b) |

The typical clearing depends on a parameter called niche radius that describes the peaks of the fitness landscape, whose value is often unknown. Another parameter, the number of winners, defines the quantity of solutions that may form a niche. After sorting all solutions by fitness in a decreasing order, they are sequentially analyzed to split the population into niches in line with these rules: (1) if no niche is yet created or the maximum possible distance (i.e., the radius) to the master of the current niche is reached, the next fittest solution is marked as the master of a new niche; (2) the subsequent solutions belong to the last created niche only if its spatial distance to its master does not exceed the niche radius; and (3) among those individuals that belong to the same niche, only a pre-set number of them are actually added to the niche as winners, while the remaining ones are marked by setting their fitness to zero. The algorithm returns in full the collection of niches that eventually emerge.

Comparable to the method described above, the adaptive clearing is an important step in VMO. After sorting the nodes in the expanded mesh according to their fitness, the best ones are meant to survive. However, the worst among those nodes closer (in fitness) than a distance threshold are removed. In that way, the clearing fosters diversity in the population, which is the reason it is planned in VMO for. Such a threshold, which is also used in the local expansion, is dynamically computed at each iteration, guaranteeing larger values at the beginning of the optimization process and smaller values at the end. Several studies [20,21,22,23] illustrate how to determine the threshold , which has a component for each j-th variable of the problem. Every single is computed by using the range that represents the domain of the of the variable , together with the amount of budget wasted from total originally given. While other notions of budget are valid, the most commonly applied in VMO is the maximum number of either iterations or evaluations of the fitness function. In any case, means a portion of the amplitud between and ; the less budget remains the shorter that portion is. The value of results from combining those of all its components, e.g., by averaging them.

In the original VMO, the adaptive clearing assures diversity among the individuals that form every initial mesh. Nonetheless, when used on multimodal optimization problems, such a clearing is also responsible for the loss of several globally fittest solutions found. In other words, it provokes the incapability of VMO to maintain the identified optima, a critical effect verified in [21]. Conversely, in [23] Molina et al. claimed to use the adaptive clearing as a niching method within NVMO, their proposal for multimodal optimization, using the dynamic threshold as the niche radius. At this point, it is important to clarify a few facts about it.

It is deductible from their pseudocodes that same as the Petrowski’s method, the adaptive clearing is capable to split the population considering the distance between the individuals. However, such division occurs in a nonconcrete way in the adaptive clearing since it does not create any explicit niche. Instead, it keeps in the population only those solutions that survive the clearing (same as in the typical VMO) as the masters of the abstract niches. While the typical clearing returns a collection of niches, each of which is formed by several winner solutions, the output of the adaptive clearing is nothing else but the contracted mesh, which consists of the masters only. That difference among both methods is relevant only if the adaptive clearing were used in any multimodal optimizer that takes into account not only the masters the niches in full. Even in such a hypothetical case, that issue is indeed easy to treat by making minor algorithmic modifications to the adaptive clearing procedure.

In its plain form, the adaptive clearing of VMO can be seen as a variant of the typical clearing, where (1) the niche radius is updated dynamically and (2) the number of winners is not taken into account, as (3) the masters are the only kept solutions in (4) the reduced population, instead of in explicit niches. Apart from the clearing procedure, other niching approaches that use the niche radius parameter, such as the classical fitness sharing [34] and the species conservation method [35], have been augmented with distinct strategies [36,37,38] to adapt the radius along the optimization process. It is logical to consider that their success strongly relies on the realism of the computed radius, for which two aspects are decisive: a good rule to modify its value and a control mechanism to stop such an update at any convenient moment. The latter is extremely hard to plan, although it is very desired. Irrespective of being increased or decreased, the updating value should reach the actual (unknown) radius, eventually. Further modifications of the niche radius will make the multimodal optimizer detect a wrongly short or large number of niches, and mayhap the recently identified ones will not appear again. A practical compensating option is to combine those revamped niching methods with other strategies within the multimodal optimizers, e.g., by saving aside the best solutions found, or by conditioning the stop of the overall optimization process to the number of the new niches found.

In VMO, the value of the threshold decreases during the search process, as explained above. However, the adaptive clearing does not include any strategy to attempt identifying when such a desired value of the niche radius is apparently reached. Instead, continues decreasing as the search process goes on. From the niching viewpoint, another issue is that is assumed the same for all the peaks in every function, which is not rare in those methods that use a niche radius parameter, making them inappropriate for those functions having several peaks of different radii. In addition, the evidence reported in [21] shows that those nodes approximating certain peaks of the analyzed benchmark problems are partially or totally ‘cleared’ from the mesh. For that reason, every time VMO jumps to a new iteration, for some of the peaks the search starts over. That happens during the whole optimization process, i.e., regardless of the value of . It is then impossible for VMO to maintain the fittest solutions. Then, how can NVMO succeed on dealing with multimodal optimization problems? And, what is the actual benefit of the adaptive clearing there? Section 3.4.1 answers both questions, while approaching the essentials of such a metaheuristic scheme.

3.4. VMO Niching Strategies

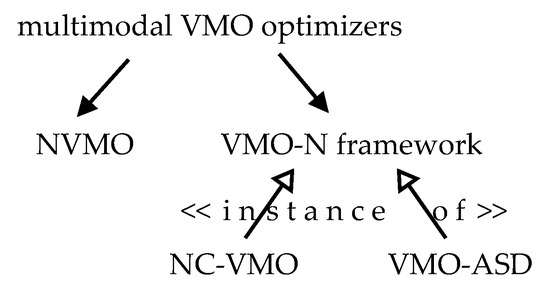

As it was originally proposed for global optimization, a few algorithmic proposals appeared to induce VMO to preserve (along the time) the multiple optima this method can find when solving multimodal problems (see Figure 2). They can be reduced to the following two approaches: the NVMO method and VMO-N, the generic niching framework for this metaheuristic. Those methods are described below in an overall fashion. Besides, considering that they are the two main adaptations of VMO to deal with multimodality, it is important to bring out a few differences between them, completing the first objective of this investigation.

Figure 2.

VMO for multimodal optimization.

3.4.1. Niching VMO

The details of NVMO were discussed by Molina et al. in [23], where authors highlighted the major augmentations to the standard formulation of VMO. They can be summarized as follows:

- With reference to the creation of new nodes from a global perspective, not only the fittest one in the population is considered for expanding the mesh. Instead, several globally best nodes are determined as those having a fitness value very similar to the best solution. Consequently, a new solution is created between every non-optimal node in the mesh and its nearest node (according to the Euclidean distance) among those marked as global optima.

- In order to improve the search capability of the metaheuristic, the Solis-West local search method [39] is run over only a certain number of nodes from the expanded mesh . The solutions selected are those located more distant from the globally fittest nodes found.

- The globally fittest nodes are kept in an external memory, whose update involves every . If has a ‘visibly’ better (>10−6) fitness than the global optimum saved, the memory restarts with only . Otherwise, means a candidate global optimum if it is ‘similar’ (±10−6) in fitness to the global optimum. In that case, the memory accepts if its closest global optima is located at a least distance denoted as the memory threshold (assumed in [23] as the accuracy level [40]).

NVMO does not split the population into niches; it accordingly executes the adaptive clearing over the whole mesh. The risk of deleting several global optima from the population persists. Thus, to keep the globally best nodes found, NVMO implements the aforementioned strategy comprising an auxiliary memory of such fittest solutions. In fact, the indubitable capacity of NVMO to deal with multimodal problems is due to the memory of optima, and not because of using the adaptive clearing with intention of niching. Such a memory is equivalent to others in previous and succeeding multimodal optimizers, e.g., the dynamic archive used in [18,30], and the elitist archive of HillVallEA.

Conforming to a common reasoning, other algorithms update the memory for the assumed global optima after executing the niching method, using the identified masters as the candidate optima. Those steps are run in the opposite order in NVMO, where such candidate solutions are selected from the entire expanded mesh, according to the explained optimality criterion, and the adaptive clearing occurs just after restructuring the memory. It means that the masters derived from that clearing procedure are not considered as the candidate optima to be kept in the external memory, a choice that might respond to a poor performance of the adaptive clearing as a niching method. Fostering diversity remains then as the main benefit of the adaptive clearing in NVMO, the same as in the original VMO. In addition, it is relevant the computational cost that the selection of the candidate optimal solutions represents in NVMO, since every single node in the mesh is processed for that, instead of considering only the masters of the identified niches.

As a multimodal method, NVMO does not rely on the niching step, but on the external memory. Thus, its effectiveness deeply counts on its search ability, strengthened by the Solis-West method. The use of local search was moved by a previous work [41] on PSO-based multimodal optimizers. In particular, NVMO runs the Solis-West procedure over a certain number of solutions in the expanding mesh, which is later completed with the new nodes resulting from that local search mechanism. After that, the list (memory) of globally best discovered solutions is updated, just before conducting the adaptive clearing over the mesh in order to prepare the population for the next generation.

3.4.2. VMO with Niching

Given in [22], the pseudocode corresponding to VMO-N suggests the moment where the niching method had better execute within VMO. In addition, it proposes to apply the adaptive clearing operator of VMO to each niche found, instead of over the whole extended mesh, as it occurs in the original form of such a metaheuristic. In that way, the efforts to assure diversity in the mesh do not affect the fittest solution (master) of each niche, which survives as part of the population to evolve. Consequently, VMO-N allows to maintain the discovered optima along the time. Furthermore, as a framework, it permits to include any desired niching method in its procedural workflow. Thus, the aforementioned instances of VMO-N are registered as NC-VMO and VMO-ASD.

The former method results from using the clearing operator by Petrowski (see Section 3.3) within VMO-N, as a niching mechanism. Obviously, it also applies the VMO’s adaptive clearing (over every niche) as a diversity strategy. Being its first instance ever, the greatest impact of NC-VMO is to put VMO-N in practice. As the standard niching method of clearing depends on the value of the niche radius, NC-VMO suffers such a drawback too, making it suitable for a short number of multimodal problems. In response to that, VMO-ASD assimilates the Adaptive Species Discovery (ASD) niching method by Della Cioppa et al. [42], which does not rely on any parameter that describes the target fitness landscape. As a result, VMO-ASD empirically shows itself as a more extensive scheme than NC-VMO. None of them is strongly competitive though, compared to outstanding algorithms in the literature. That leads to the seek for a strong VMO-N variant, a need that is fulfilled in this study.

Before dealing with that shortcoming about the effectiveness of specific instances, the building blocks of VMO-N should be revised. As a framework, it should offer not only the possibility to properly incorporate any niching mechanism of preference (it can be decided freely), but also the chance to conduct further algorithmic strategies which might support the discovery of the niches and their maintenance along the time. In other words, VMO-N has to become a more flexible proposal by considering the inclusion of multiple (likely optional) procedural steps, which will also reinforce the generalizability of the framework.

3.4.3. Divergence between VMO-N and NVMO

For a better comprehension, Table 1 summarizes the most relevant dissimilarities between both approaches. One of the most obvious is the external memory used by NVMO to keep the set of global optima discovered. The application of the adaptive clearing either over the whole mesh or over each niche is a crucial difference here. However, the most significant contrast is given by the underlined algorithmic sequences. The implication of this matter is not trivial though. In Section 4, we revise the VMO-N framework. Consistent with that, future instantiations of it might use an external memory or avoid the action of the adaptive clearing, etc. Regardless of the procedural choices taken, no new case of VMO-N will ever conduct the niching process just after an external memory is updated. It does not contradict the possible modification of such a memory, followed by the application of the adaptive clearing but only as a strategy to sustain diversity in the population. Moreover, in that case it would still be run over every single niche, not over the entire mesh. Among other critical individualities, these last remarks derived from the analysis of their algorithmic constructions, sufficiently justifying that no future variant of VMO-N will match the NVMO method.

Table 1.

Major differences between VMO-N and NVMO.

3.5. Hill-Valley Evolutionary Algorithm

This method is closely related to the new version of VMO-N, proposed in this paper. Hence, it is important to recapitulate the fundamentals of the HillVallEA, whose main modules are the niching technique, the core search method, and the restart scheme with an elitist (external) archive. This subsection addresses such elements, before relating that EA from a general outlook.

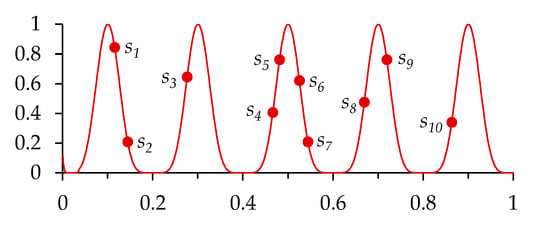

3.5.1. Hill-Valley Function: A Pivotal Subject for HillVallEA

The hill-valley function (HVF) [43] is a mathematical abstraction acknowledged in the field of multimodal optimization and thus used by several niching approaches, e.g., the aforementioned ASD. As explained afterward, the HVF-based test is strategic in HillVallEA. The functioning of it concerns the quasi-convexity/quasi-concavity of in particular subspaces. Let us the points and refer any pair of solutions () in an optimization landscape, like in Figure 3. To decide if such two solutions are not in the same niche, some test inner points are generated. If any single test point is poorer in fitness than both and , they are said to exist in different peaks of the objective function, i.e., they belong to separate niches. Thus, and are admitted to go in distinct peaks since at least has worse fitness than both of them. With less fitness than only one the target solutions, the test point cannot separate them. The result is then influenced by the number of inner points and their location.

Figure 3.

HVF test. It finds and in distinct niches if () has less fitness than them.

Moreover, if none of the test points is found to have a worse fitness value than both and , it may be supposed that they belong to the same peak, but it cannot be affirmed. That occurs if and are the test points for and , which are in the same peak; also if and are used as test points for and , located in separate peaks. Hence, the only possible reliable conclusion by this test is that the two target solutions are in different peaks, if any of the inner points can prove it. Otherwise, the algorithms that split the population into niches via HVF, such as HVC, assume that those solutions are in the same niche, on risk to fall in the false-positive case described above. Testing a large number of inner points is a logical intent to avoid that, but this is not feasible as it also increases the computational cost. Thus, proper mechanisms to complement the power of this test are required.

3.5.2. Hill-Valley Clustering: The Niching Method

By adopting the HVF-based test, the Hill-Valley Clustering algorithm shapes the niching plan for HillVallEA. The strategy of HVC to benefit from the HVF-based test is disclosed in [24]. That includes a routine to suggest the number of (equidistant) test points between two solutions, which is directly proportional to the Euclidean distance between such them. Besides, HVC implements a refined seek for the cluster that any given individual belongs to, among those already identified. Given a selected population () sorted by fitness, excepting the initial solution, i.e., , which is directly assigned to the first cluster created, each solution , with , is contrasted with up to nearest fittest individuals via the HVF test. Among the solutions that exhibit a better fitness than , it is tried with the closest one, and then with the second nearest, and then with the third one, and so on, until is found to belong to the same cluster that some of such tested solutions. After comparisons with negative result, initializes another cluster.

Originally, that process was repeated for a total of individuals, after which a resulting collection of clusters emerged as the found niches. Later [27], the authors concluded that it is worthy to contrast a given with multiple top fittest neighbors only in two specific situations, which reduces the computation time to run the HVF-based test. The first scenario happens when is one of the solutions with better fitness. Otherwise, is tested with the neighbor at hand only if they are separated by at least the expected edge length [24], which is the theorized distance of any pair of individuals equidistantly positioned in the search space. If it does not fall in any of those two cases, checking several fittest neighbors for leads to discover accurate clusters but having a poor quality. Subsequently ‘forgotten’ by HillVallEA, they mean a waste of both the budget allotted to solve the problem and the computational effort. That principally concerns those problems with many local optima of very low fitness. Such a decision can be easily reconsidered in future versions of HillVallEA that intend to find not only the global optima, but the locally optimal solutions as well.

3.5.3. AMaLGaM-Univariate: The Core Search Method

HillVallEA is flexible about the incorporation of core search algorithms, as any can be freely included at no risk of interfering with any other fundament of such a scheme. Among other methods examined, AMaLGaM-Univariate performed stunningly within such a multimodal optimizer. That election resulted in the HillVallEA-AMu algorithm [24], renamed as HillVallEA18 and then refined as HillVallEA19, in [27]. The AMaLGaM-Univariate procedure is catalogued as an estimation of distribution algorithm (EDA) [44], a sort of EA suitable for those optimization tasks with a lack of knowledge about the objective function [26], e.g., the multimodal problems. Earlier studies [45,46,47] reported the use of EDAs to deal with multimodal optimization as well.

The EDAs seek for convergence by sampling a probability distribution updated all through the optimization process [26,44]. Hence, the focal action in every iteration is the estimation of such a distribution from the fittest individuals in the population. By using the distribution, a new generation of individuals is created to replace the formers, either fully or partly, after which only the best solutions remain in the recent population. Among the EDAs in the state-of-the-art on evolutionary computation, Bosman et al. [25] contributed the Adapted Maximum-Likelihood Gaussian Model Iterated Density-Estimation Evolutionary Algorithm, abbreviated first as AMaLGaM-IDEA and later as AMaLGaM. In [26], they analyzed three versions of AMaLGaM, basically differing on the Gaussian distribution used, being either fully multivariate, Bayesian factorized or univariately factorized. The last one led to AMaLGaM-Univariate, the succeeding core search method in HillVallEA.

The Gaussian probability distribution is conditioned by a vector of means () and a covariance matrix (). Given a cluster of solutions, that distribution is initialized in AMaLGaM-Univariate by taking as the cluster means, and as the covariance matrix of such individuals respecting . Then, a population with a size is sampled, according to the initial distribution. In the each of next iterations, both and are re-estimated and the population is later re-sampled. That repetitive procedure evolves to a success stage, after which the fittest solution is returned. Thus, the main parameters required by AMaLGaM-Univariate are the cluster per se (from which and are initialized), and . The later is coined as the ‘cluster size’ although it does not refer the number of individuals in the given cluster, but the size of the population used to optimize it. A value of tolerance is used to terminate AMaLGaM-Univariate when it is converging either to a presumed local optimum or towards an already assumed global optimum. The latest case is validated every five generations. Planning future variants of HillVallEA to find both global and local optima, requires one to modify such conditions to stop AMaLGaM-Univariate when converging again to the same optima (global or local). Nevertheless, the core search algorithm safely stops in other situations, e.g., when either the standard deviation of the solutions or the standard deviation of their fitness values is extremely small.

3.5.4. Elitist Archive, Restart Scheme and Overall Process

As to maintain the elites, i.e., the masters of the peaks, HillVallEA uses an archive that in practice works alike the external memory in NVMO. Some facts differ in the mechanisms that control such structures though. For instance, the candidate optima (masters) to update the elitist archive are not picked by checking the entire population exhaustively. Other particularities of the strategy to update towards the end of every evolutionary iteration are described below. The algorithmic details about HillVallEA addressed in this study combine from the two fundamental works [24,27], and the source code [48] that the authors unveiled under GNU General Public License v3.0. For their relevance to HVcMO (part of the proposal in Section 4), such details are simplified in Algorithm 3.

The evolutionary process is repeated while the remaining budget (function evaluations) is enough to at least generate other individuals (Algorithm 3, line 5). In each iteration, a population of individuals is randomly initialized according to a uniform distribution, and by applying a rejection strategy that came with HillVallEA19 (the latest version) to avoid re-exploring regions of the search space (line 6). Any new solution is very likely discarded (rejection probability ) if its nearest solutions in the initial population of the prior generation were in the same cluster. Actually, solutions are created with that rejection reasoning, but only are chosen via a greedy scattered subset selection mechanism [49], to spread the initial population as it has proved to help the performance of EAs [27]. Once initialized, the population shrinks again, this time to a certain percentage indicated by the selection fraction : out of the individuals, the fittest ones are taken. That seeks for higher outcomes by the overall optimization. The population is then made ready to be partitioned in niches. It is completed with those solutions stored in the elitist archive (line 10), so that they can work as attractors during the niching process, subsequently conducted via HVC (in line 11).

Being the recent set of clusters, the core search method singly improves each () whose best solution () does not match any former elite. Hence, the best solution in each final population by the core search method supposes a global optimum (line 15). The set of candidate optima is checked for updating (in line 19). If the fittest candidate optimum exceeds the best elite in the archive, it is emptied. As well, those candidates poorer in fitness (by at least the given tolerance value) than the globally best solution, are labeled as local optima and then discarded. The others are assumed as global optima and included in if they are new elites, i.e., they belong to different peaks than those already in the archive, which is checked by using HVF with five inner points. Otherwise, the presumed global optimum replaces the equivalent stored elite only when having a greater fitness value. In that way, this procedure intends to avoid cloning any saved optima.

| Algorithm 3 HillVallEA | ||

| Inputs: | -dimensional problem as in Section 2, plus the following main parameters: | |

| : the core search algorithm (e.g. AMaLGaM-Univariate) | ||

| : population size (in HillVallEA19: 64; in HillVallEA18: ) | ||

| : increment factor for the population size (suggested value: 2.0) | ||

| : recommended population size for (for AMaLGaM-Univariate: ) | ||

| : initial fraction of the population size of (in HillVallEA19: 0.8; in HillVallEA18: 1.0) | ||

| : increment factor for population size of (in HillVallEA19: 1.1; in HillVallEA18: 1.2) | ||

| : selection fraction for (for AMaLGaM-Univariate: 0.35) | ||

| : tolerance (by default: ; it may be set equal to the accuracy level) | ||

| : budget expressed as the Maximum number of Function Evaluations | ||

| Process: | ||

| 1. | // Actual population size for | |

| 2. | ||

| 3. | // Elitist archive | |

| 4. | ||

| 5. | while do | // Enough to prepare solutions? |

| 6. | ||

| 7. | // Population backup | |

| 8. | ||

| 9. | // Portion of said by | |

| 10. | ||

| 11. | ||

| 12. | // Set of candidate global optima | |

| 13. | for to do | |

| 14. | if then | // If the master of is not a prior elite, |

| 15. | // run to enhance that niche; take the | |

| 16. | // fittest solution as a candidate optimum | |

| 17. | end if | |

| 18. | end for | |

| 19. | // Count elites either replaced or added | |

| 20. | if then | |

| 21. | // If remains unaltered, increase | |

| 22. | // both population sizes | |

| 23. | end if | |

| 24. | end while | |

| Output: | ||

| 25. | return | |

In spite of the described efforts, in some cases no novel elite is detected. Authors ascribe that to a couple of possible reasons. The first one alludes to a population still insufficient to catch minor niches. The other supposition is that the number of individuals used by the search core method is inadequate to enhance complex niches. To cover both cases, the restart of the population for the next cycle considers a larger number of individuals, while the core search over each niche will also use an increased number of solutions (see Algorithm 3, lines 21 and 22).

A decisive matter to solve any optimization problem by using metaheuristics is the number of solutions required for it. Looking for multiple optima presupposes the demand for more individuals. Besides, some objective functions can be approximated with less solutions than others. Tuning the population size is definitely a challenge. In HillVallEA, such an amount is relatively short at first, and increments upon analysis. Besides, the initial size of the population changed from , in HillVallEA18, to 64 individuals in HillVallEA19. That signifies a smaller number of initial solutions for all problems with . In addition, as shown in Algorithm 3, HillVallEA19 uses lower values for both the initial fraction of the population of the local search method, and the factor that controls its increment. In spite of that, our observations (documented in Section 6) show that this method continues employing quite large populations to approximate well most problems at hand. This important drawback markedly prolongs the running time, which drafts the next research goal of this paper, i.e., to lower such an execution time without any serious loss of effectiveness.

Because when it comes to metaheuristics, it is key to monitor the time, our concern about it is in consonance with a few algorithmic conceptions of HillVallEA. That includes the aforesaid adjustment of the parameters related to the population size. As well, to effect Hill-Valley Clustering over the set of selected solutions, for each analyzed individual, the computed distances to all the solutions better than it are stored. Such a decision makes HVC more efficient, as its complexity noticeably drops from to . In addition, while avoiding re-examine areas of the search space, the restart scheme with rejection reduces time. That benefit is accentuated by using the subset selection method referred above, among other possible techniques that become inefficient when either the dimension of the problem or the sample size is large [27].

3.6. Research Objectives

The early declared research goal is actually attained above. Even so, just for correctness, it is recaptured as:

- (1)

- To compare VMO-N and NVMO from a conceptual perspective

The previous examination of both VMO-N and HillVallEA put emphasis on their shortcomings. The main needs for research derived from those limitations determine most of the objectives of this investigation, recapped below in a clear manner:

- (2)

- To revise the VMO-N framework

- (3)

- To create a competitive variant of VMO-N

- (4)

- To decrease the running time of HillVallEA while keeping it effective

Apart from those, a last need appears from a practical perspective. By confirming which of the relevant methods (previous and newly proposed) performs better on dissimilar test problems, it is easier to choose between them to approximate further (likely real-world) problems, having common features with the ones used here for benchmarking. In simple words, we pretend to answer the following question: is there any range of multimodal optimization problems for which one or the other analyzed method are preferred? That leads to the final research objective of this work:

- (5)

- To find guidelines to select between past and new methods to better solve additional problems

This requirement derives from the well-known ‘no free lunch’ theorem [50], which supports that no metaheuristic absolutely outperforms all the others. Thus, none of them can solve any particular problem better than every remaining heuristic optimizer, irrespective of the subfield of optimization affected. It is then useful to have evidence for selecting methods to deal with upcoming problems.

4. The Proposals

In response to the second goal projected, this section presents the VMO-N framework with several improvements that guarantee a high flexibility. This new scheme constitutes the base for creating future VMO multimodal optimizers, such as the HVcMO algorithm, also introduced below.

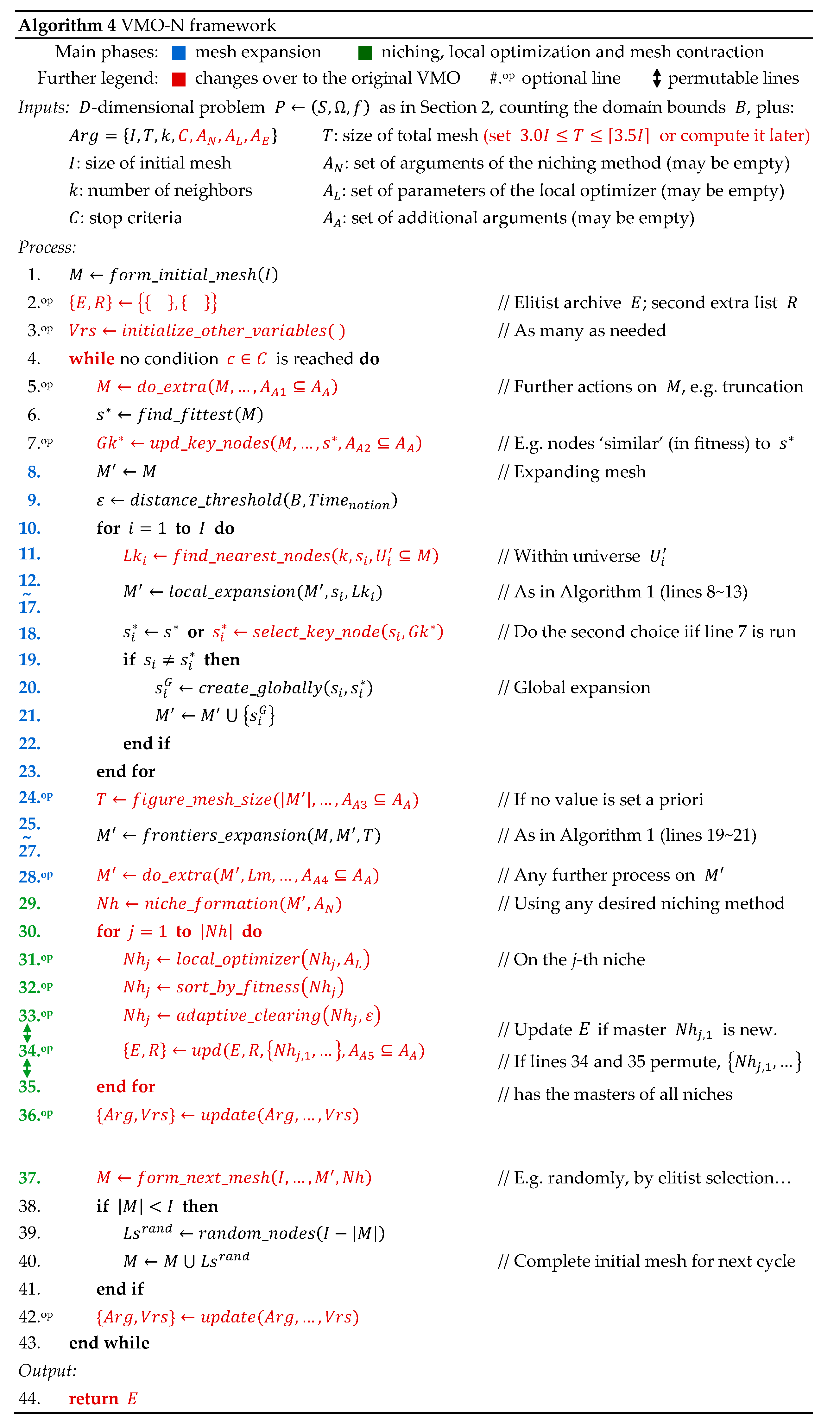

4.1. Variable Mesh Optimization with Niching: A Revised Framework

This fresh proposal preserves the essential contributions of VMO-N: (1) advising when to better apply the niching step within VMO, and (2) applying the adaptive clearing operator over each niche. However, it comes with a strong adaptability by reason of the multiple optional commands, as Algorithm 4 explains. One of them is the use of an elitist archive , a memory-based strategy imported from the literature. It has shown helpful in many multimodal optimizers [18,23,24,30,37], some of which were previously approached in this paper. Apart from the masters of the peaks, it might be helpful to store other nodes with additional purposes. Hence, it is optionally considered a second external list, indicated as in the framework.

The previous works about VMO-N overcame the initial shortcoming of VMO related to its incapacity to maintain the fittest found nodes in the population along the time. Given that, memorizing such nodes is unnecessary, unless certain circumstances apply, e.g., if they are required for implementing any mechanism, like the ‘tabu’ list in [37], to explicitly avoid re-visiting regions of the search space. However, this revamped VMO-N considers the possibility that the best individuals discovered are deliberately excluded from the mesh for the next iteration, either temporarily or permanently. In that situation, is extremely needed.

Other optional instructions are carefully placed in the building blocks of VMO-N. Besides providing adaptability to that multimodal optimization scheme, they make it more generalizable, which means that its instances can deal with a vast amount of multimodal problems. A plethora of methods can be created by instantiating this framework in future. Actually, some of those non-compulsory commands indirectly suggest further strategies to apply. In addition, the number of parameters used and of variables declared is as large as needed, for example, by the niching algorithm incorporated or by any elective step conducted.

Based on the outcomes in [23,24], an important increase is the possibility of a local optimization step (Algorithm 4, line 31). In order to enhance the search, any freely chosen optimizer is separately run over each niche fund. It is said a local optimizer as it initializes from the individuals in a given niche, using either some of them or all. However, it might reach solutions in other areas of the search space, beyond the limits of the niche at hand. Following the main course of VMO-N, once it has been improved, the adaptive clearing affects each niche (in line 33) and then, the fittest node in the niche (indicated as ) is considered to update the list of elites only if was discovered just now. Moreover, in case of using the second external list (), it is updated at that moment as well.

There are a couple of alternative courses involving the update of the memories (line 34), taking into account that it can be permuted either with line 33 or with line 35. If the order of the instructions in lines 33 and 34 are exchanged, the adaptive clearing occurs after updating the lists. In fact, that possibility was announced in Section 3.4.3, while explaining that even in that case the algorithmic sequence of any instance of VMO-N will differ from that of the NVMO algorithm. Such a modification has sense if, for example, several nodes have to be saved in the second extra memory before they are removed by the adaptive clearing operator.

On the other hand, permuting lines 34 and 35 indicates that the memory update happens at once, after processing all niches, instead of after processing every single niche. In that case, the set contains the master of each j-th niche to update , together with other relevant nodes to update . What is more, it is possible to update one of the lists ( or ) inside the for-loop, every time a niche is processed, and the other list after that, only once. That alternative derives from the separability of both lists, and from the permutability of line 34. Nonetheless, effecting the adaptive cleaning (line 33) is no longer obligatory, because other mechanisms may satisfy its main function: to foster diversity in the mesh.

The VMO-N framework also integrates the notion of what we coin as global key nodes. That implies not only the single fittest solution but any other with global importance, for example, every node having similar fitness than the best solution in the population. Whenever that option is taken, the global expansion of the mesh takes into account the set of such key solutions. Likewise, the local expansion is slightly adapted. Given any node, its neighbors are not necessarily selected from the whole mesh. Instead, they are found among those nodes belonging to a certain universe that is specifically defined for the i-th node, as a subset of the sampled mesh, that is .

The annotated restriction derives from the details of the expansion. Setting assures a least creation of nodes, which is enough to expand locally, globally, and to some extent, from the frontiers. Moreover, benefits even more the creation of solutions from the frontiers. Actually, is more than sufficient to treat both frontiers fully. Instead of setting as a parameter, now VMO-N can also compute it as needed, for example to precise the exact wanted. If is very small, can be obtained. In addition, even if is set as a parameter together with , they may vary along the search (either in line 36 or in line 42).

Other revisions are the operation with several termination criteria for the evolutionary process, and the use of a while-loop rather than a for-loop to describe it. Although the latter is coherent with our practice of VMO, it has no other impact but gaining descriptive capability for future. The altered framework remains valid to pursue both global and local optima, whereas it allows limiting the search to only one of those types (e.g., by means of lines 34 and 37).

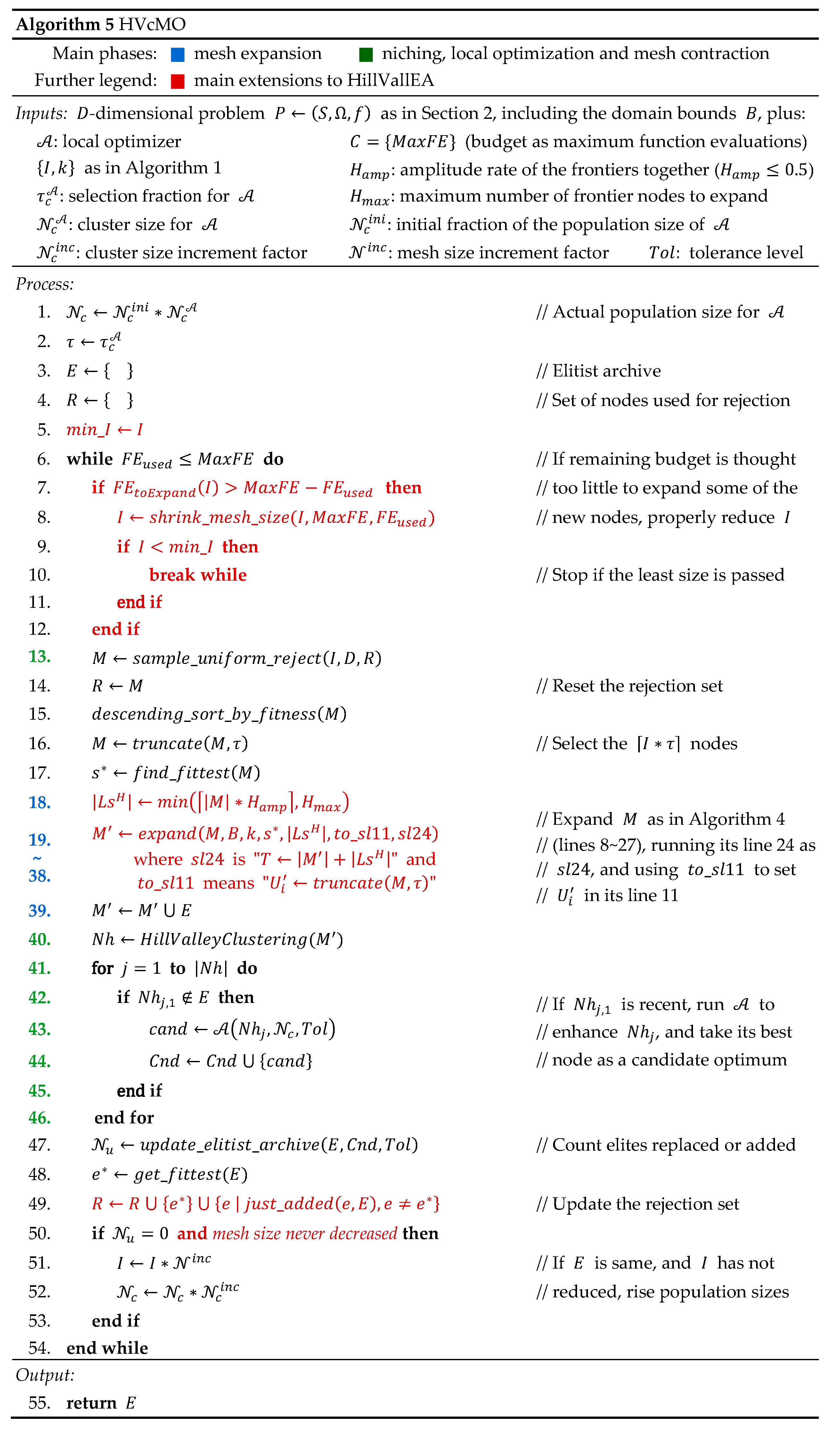

4.2. Hill-Valley-Clustering-Based Variable Mesh Optimization

Algorithm 5 reveals the elementary units of HVcMO, the novel instance of VMO-N, whose competitiveness is later confirmed in Section 6, as to accomplish the third research objective of this study. It is also an evident extension of HillVallEA that integrates some important additions. Thus, HVcMO is seen from the perspectives of its two parents. In this new case of the VMO-N framework:

- two external lists are used to keep the elites and those nodes for rejection, respectively,

- HVC is employed as the niching algorithm,

- the adaptive clearing is not applied,

- a local optimizer is run over each niche, and

- the mesh in the next generation is fully replaced by a new one.

Since the mesh is entirely reset (line 13), an elitist archive is required and the adaptive clearing is needless. The pursuit for diversity recurs, now by the rejection scheme all along the restart of the population, which follows the instructions for HillVallEA, same as the update of the archive. Besides, before niching the expanding mesh, it is enlarged with all the already identified elites (line 39) to use them as attractors while executing the niching method. That is equivalent to evolve a population that consists of two consecutive segments for certain masters of the found niches and for random nodes, respectively, so that the sorting, the truncation and the expansion affect only the latter segment.

Moreover, the search operators of VMO were implemented the same as for [20,21,22]. The corresponding formulations given in [20] largely apply, except for some changes that involve mainly the local expansion. Among them, the distance threshold is based on [21,22], as:

where is the poblem dimension and each component denotes a portion of the amplitude of the domain of the j-th variable whose upper and lower bounds are respectively and . That fraction depends on the current count of function evaluations, out of a fixed maximum number ():

Besides, for every node to be expanded locally by the F-operator, the list of neighbors is not determined from the entire mesh but from a certain universe . In HVcMO, regardless of the node at hand, such a universe is the fittest -fraction of the mesh. As for that, we use the selection fraction defined for the truncation of the initial mesh, but they may also be set unequally. Not all the solutions in have global importance, even for relatively short values of . For that reason, that universe should not be confused with a set of key nodes. The larger is, the more nodes with no global relevance are included in . The choice of that quasi-local F-operator is mostly moved by our concern about the running time. Future works should evaluate the effects of other ways to decide .

The formulations for the G-operator and the H-operator remains unaltered, but the size of frontiers affected by the latter is jointly delimited by their fixed amplitude ratio . In the previous studies about VMO, the value of is fixed as a parameter, informing the possible largest length of the mesh after the expansion. Thus, the extent of the creation of nodes from the frontiers, i.e., , is basically figured as the difference of and the size of the enlarging mesh (Algorithm 1, line 19). In that case, the proportion of the mesh taken as frontiers is influenced by . Conversely, in HVcMO, is computed as the lowest value between the percentage of the initial mesh indicated by , and a firm upper limit () for the size of the frontiers (Algorithm 5, line 18). Next, in lines 19~38 that are equivalent to lines 8~27 in Algorithm 4, it is marked how to calculate . Note that it is just a formalism to trace from Algorithm 5 to Algorithm 4, and then from Algorithm 4 to Algorithm 1, as to figure . In practice, after calculating , HVcMO does not utilize any at all.

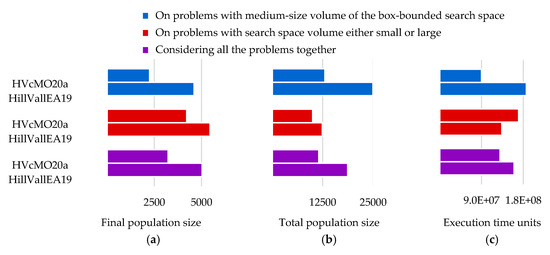

From the viewpoint of HillVallEA, the biggest augmentation in HVcMO is the effecting of the search operators of VMO (lines 18~39) over the truncated population. As of the population is restarted randomly, HillVallEA uses a couple of important strategies, i.e., the rejection mechanism to sparse the solutions through unexplored areas of the search space, and the subsequent truncation to process only the best part of the population. The adding of the expansion operators of VMO as another preparation step before niching intends to improve the quality of the population as well. However, it provokes that the number of nodes increases, and then also the consumption of the budget and the execution time. That consequence applies for any specific sample size at a certain moment, but is not necessarily valid for the entire evolutionary optimization. Our conjectures about it are delineated as:

- Hypothesis 1: Using additional search operators to enhance the population before niching may reduce the total number of solutions throughout the optimization process by HillVallEA.

- Hypothesis 2: If the reduction of the overall number of solutions is big enough, the total execution time of HillVallEA should also decrease, while keeping quite similar multimodal capability.

To evaluate them (in Section 6), we borrowed search procedures from VMO. Others may be used instead, e.g., crossover mechanisms designed for GAs. Thus, a research avenue for HillVallEA begins. Another variation by HVcMO concerns the diminution of the mesh size when the remaining budget is insufficient to deal with a new population having the current length. This choice was indeed contemplated by Maree et al. in [48], but discarded, as they considered fruitless to sample such small populations at the end of the optimization process. In case of HVcMO, the size of the mesh properly decreases (line 8) when the available budget is insufficient not only to sample a population with the current size, but also to expand at least part of the new nodes, via VMO. Even without any deep analysis about it, we implemented that modification based on some empirically observed benefits. Besides, it slightly increments the overall number of solutions and thus, the running time. Therefore, that means a practical opportunity to prove that even with a forced longer execution time (beyond that provoked by VMO itself), HVcMO can run faster than HillVallEA. However, future works should verify the actual advantages of keeping such a late shrinkage of the population in HVcMO.

As an aftermath, the condition to increase the size parameters (line 50) is altered. In HillVallEA, that occurs if no new peak is detected. In HVcMO, it happens if also the size of the population was never reduced, since it is senseless to push a larger mesh again after it was previously shortened due to a lack of budget. On the other hand, one more extension pretends to reinforce the potential of the rejection while sampling the population. Not only the solutions sampled in the preceding iteration are considered, but also each master representing a newly discovered peak (in the current iteration), together with the best elite ever found (line 49). A closing comment clarifies about HVcMO20a, which is nothing else but the HVcMO algorithm where AMaLGaM-Univariate performs as the local optimizer and the parametric specifications for HillVallEA19 are widely adopted, as detailed below.

5. Experimental Setup

The general elements of the experimental analysis are explained in this section. They include the setting of parameters for HVcMO20a, the suite of benchmark problems, the baseline methods, the performance criteria, and the statistical tests for comparisons. This work follows the procedures of the Competition on Niching Methods for Multimodal Optimization within GECCO [28], which extensively embraces the instructions in [40]. For any single run, the tried algorithm stops when a given budget is finished. Stated as a certain maximum number of functions evaluations (), the budget for every test problem is specified in Table 2. Every algorithm is run 50 times over each test problem. The outputs are assessed at five levels of accuracy: , , , and , and the results are averaged over a given number of runs () at every level of accuracy. Such a concept of accuracy is meant only to evaluate the outputs of any multimodal optimizer. However, methods that use certain thresholds, e.g., the tolerance in HillVallEA, may set them by considering those values of accuracy as a reference.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the test problems and budget allowance. Each value in red represents a search space volume that is either small or large; if blue, it denotes a volume of a medium size.

5.1. Configuration of Parameters of HVcMO20a

Equivalent to in HillVallEA, the size of the initial mesh is set as , setting a selection fraction of The number of neighbors of each node when affected by the local expansion is , the same as in [20,21,22,23]. HVcMO20a takes AMaLGaM-Univariate as the local optimizer and then, the size of the population to enhance every niche (by means of HVC) is (the values of are shown in Table 2), and its initial fraction is . The increment factors for the length of the overall population and the cluster size are fixed as and , respectively. The level of tolerance is set to , except for the later estimate of the time ratio (see Section 6.3). The domain bounds () for the variables of each problem are also given in Table 2.

Furthermore, the frontiers are jointly delimited by an amplitude rate of , and the nodes to generate from them are at most . Hence, while in the evolutionary optimization the length of the initial mesh grows in the range , it is truncated to nodes and therefore, the number of nodes to expand from the frontiers is . For larger initial meshes, keeps at constant value of 50. This choice of effecting the H-operator over a few solutions responds to the outcomes by previous works and some analytical observations. Despite the frontier operator was found useful for global optimization with VMO [32,51], there is no evidence of its impact on the VMO-based multimodal optimizers. Indeed, that represents another pending research issue, in particular since we noticed a detriment of the performance of HVcMO in some cases when the H-operator is applied on the large scale. We keep the usage of the frontier operator at a low rate, based on such yet incomplete findings, and also on the outcomes unveiled in [51], where it is proved the less influential among the search operators of VMO for global optimization.

5.2. Benchmark Multimodal Problems

A standardized test suite is used, being the number of problems. Table 2 summarizes their main features, detailed in [40], plus the specified as the budget afforded. The objective functions are formulated in [40], as well. We add information about the volume of the box-bounded search space; it is expressed as the product of the amplitudes of the domains of all variables:

being the dimension, and and the respective upper and lower bounds of the j-th variable. Values are highlighted (in red or blue) according to the volume, empirically seen as small (), medium () or large (). This issue gains importance in Section 6.

5.3. Baseline Methods

As part of the experimental analysis, HVcMO20a is compared to the other VMO-based multimodal optimizers, namely NC-VMO and VMO-ASD (the previous instances of the VMO-N framework), and also the NVMO method. Besides, HVcMO20a is contrasted with the HillVallEA19 algorithm and its predecessor, HillVallEA18, as well as with other remarkable metaheuristics such as NEA2+, proposed by M. Preuss in [52], and RS-CMSA, introduced by Ahrari et al. in [53]. The other included baselines are SDE-Ga and ANBNWI-DE, by Kushida, respectively ranked first and second in the last two editions of the abovementioned competition, whose results are reported in [54].

5.4. Major Performance Criteria

The following description concerns the standard measures utilized for comparing HVcMO20a with the group of baseline optimizers, while additional criteria are later used to contrast it only with HillVallEA19, regarding their running times (Section 6.3). According to the most recent procedures indicated for the referred competition, every method is assessed by taking into account three scenarios defined by these scores: the peak ratio (), the (static) measure and the dynamic . They are bounded in ; the larger, the better. Among them, the allows contrasting new algorithms with a larger set of earlier multimodal optimizers, even if not recent ones, since the other two criteria were just adopted in the last years. For any specific run, the is the percentage of the number of peaks found () out of the number of known peaks (), keeping in mind that such peaks represent global optima only:

Additionally, the well-known statistic measure is re-formulated in this context as follows:

where given the set of output solutions (), i.e., the presumed global optima returned by the algorithm, the success rate of tells the fraction of actual global optima found with respect to the count of output solutions:

It is important to distinguish from the success rate () of runs [40], a formerly used measure. Furthermore, after a run is finished, the achieved set is entirely used to compute the static , while the dynamic is progressively calculated at the moments when solutions are discovered. Thus, such a calculation considers the count of function evaluations () at the instant i, with , which corresponds to the i-th found optima in . The set then consists of the first i optima located. Finally, the dynamic is figured as the area under the curve divided by the allotted:

5.5. Statistical Validation

Regardless of the measures, the advices by Demšar [55] for comparing classifiers using non-parametric tests turned into a universal practice to assess methods in several fields, e.g., evolutionary computation [56]. However, as we alerted [22], such statistical comparisons are common in studies on global optimization, but sporadic in those about multimodal optimizers. For the validation of the outcomes by HVcMO20a, we apply the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test to contrast pairs of algorithms, and the Friedman test to detect significant differences between a group of methods. The non-parametric analyses aim to reject the null-hypothesis (H0) that the compared algorithms perform similarly. If the Friedman test does it, we use the post-hoc Nemenyi test to identify which methods differ significantly, concerning the measure at hand. The election of this last procedure responds also to the intention of contrasting, in unison, the earlier versions of HillVallEA with other multimodal optimizers, from a statistical perspective. Here, we set the significance level at 5%, i.e., the confidence level is .

6. Discussion of Results

The output files of HillVallEA19 that led to the statements presented in [27], are now available online [54]. However, it was necessary to compute further rough data, e.g., the population size at the end of each iteration of the algorithm, as to conduct the analysis given in Section 6.3. For that reason, we executed HillVallEA19 again by using its original program [48]. Hence, for a matter of homogeneity, we calculated the , and dynamic for the new output data in order to use their values also in the Section 6.2, instead of the ones published in [27]. As expected, the values for those metrics in both studies are quite similar. In view of that, if the analysis related to such measures is replicated, assuming the numbers in [27], it will lead to equivalent ends. As Supplementary Materials, the output files of our runs of HillVallEA19 and HVcMO20a are accessible online [57], in the required format [28], where the times reported have no other use than checking the correct order of the output solutions recorded; those values of time are not considered for the experiments in this study.

6.1. Outperforming NVMO and Earlier Instances of VMO-N

According to the availability of performance data, HVcMO20a is contrasted with the previous VMO-based multimodal optimizers by means of the peak ratio only. Table 3 shows the average assessments (at all accuracy levels) of all runs over the whole test suite, for each algorithm. In case of NC-VMO and VMO-ASD, the comparisons are based only on the results for 6 and 8 problems, respectively, which are reported in [22]. On the other hand, the results considered for NVMO involve the full validation suite of 20 problems, as published in [23]. The results by HVcMO20a over every single benchmark function are detailed in Table A1 from Appendix A.

Table 3.

Peak ratios reached by the VMO-based multimodal optimizers, averaged at all accuracy levels over sets of 6, 8 and 20 benchmark problems.

Although the overall PR values put HVcMO20a on top of all these methods, the application of the Wilcoxon test over each pair of algorithms is required to deepen the analysis. Table 4 confirms that HVcMO20a significantly outperforms both VMO-ASD and NVMO, regarding the peak ratio. About the remaining evaluation (HVcMO20a vs. NC-VMO), it takes into account six problems; for two of them, those methods achieve equal outputs. Thus, there are only four relevant comparisons, a sample size that is insufficient to make a reliable computation of the Wilcoxon test. Alternatively, it is possible to calculate it with the 6 comparisons as relevant by splitting the ranks of such two ties evenly among the sums R+ and R−. In that variant, the R+ would be 19.5, while both R− and the W statistic would be equal to 1.5, which is greater than 0, the critical value of the Wilcoxon test for 6 paired comparisons at , making the test unable to reject the null-hypothesis. Hence, no significance difference between the peak ratios scored by HVcMO20a and by NC-VMO are detected with the studied data.

Table 4.

Wilcoxon test regarding PR. The sum of ranks of comparisons where HVcMO20a outdoes the other algorithm (either VMO-ASD or NVMO) is R+, and R− is the opposite sum. If the W statistic is equal or less than the corresponding critical value, the null-hypothesis is rejected.

6.2. Further Baseline Comparison

Different from above, HVcMO20a is contrasted with the previous variants of HillVallEA and other outstanding meta-heuristics by means of the PR and the two other scenarios, i.e., the static and the dynamic . The mean results of our executions of HVcMO20a, HillVallEA19 and ANBNWI-DE over the benchmark problems are shown in Table A1, in Appendix A. For ANBNWI-DE, we computed the performance scores by using the output data available in [54], same as for the other baseline methods: NEA2+, RS-CMSA and SDE-Ga. However, we do not report the calculations for the last three algorithms because they match those published in [27], in relation to them.

Table 5 exhibits the average measurements for the multimodal optimizers, considering all accuracy levels and the whole set of problems. The group of HillVallEA methods, including HVcMO20a, beat the rest of the algorithms in every scenario. Among them, HillVallEA19 shows the best performance, closely followed by HVcMO20a and HillVallEA18, in that order. However, is the advantage of the HillVallEA family over the remaining algorithms significant? How about the differences within the three variants of HillVallEA?

Table 5.

Scores averaged at all accuracy levels over the entire validation suite.

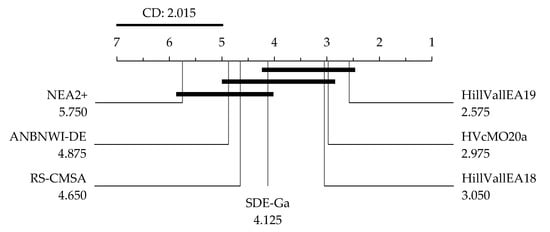

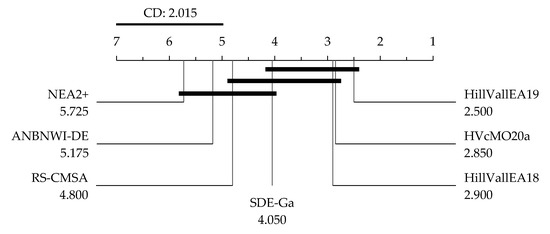

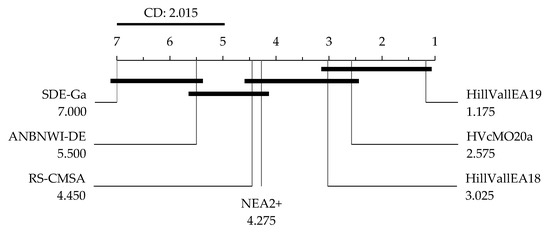

The Friedman test confirms the existence of significant differences in the pool of methods at every scenario (see Table 6). Therefore, a post-hoc examination should determine which algorithms perform significantly distinct. That is clarified in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, the graphical representations of the implication of the Nemenyi test for the scenarios of , and dynamic , respectively.

Table 6.

Friedman test. Since p-value < 0.05 (α), each null-hypothesis is rejected.

Figure 4.

Nemenyi test regarding PR. Connected optimizers are not statistically different.

Figure 5.

Nemenyi test regarding F1. Connected optimizers are not statistically different.

Figure 6.

Nemenyi test regarding dynamic F1. Connected optimizers are not statistically different.

For seven algorithms and 20 comparisons (benchmark problems), the critical difference (CD) for the Nemenyi procedure at is 2.015. Any two algorithms perform significantly distinct if the distance between their average ranks is at least CD. Although HillVallEA19, HVcMO20a and HillVallEA18 confirm to rank before all the other methods, there is no significant difference between the three of them at any scenario. Thus, the performances of such three algorithms are statistically equivalent. Regarding the peak ratio, HillVallEA19 significantly outdoes RS-CMSA, ANBNWI-DE and NEA2+. Both HVcMO20a and HillVallEA18 are significantly better than NEA2+.

With respect to the measure, HillVallEA19 statistically beats again RS-CMSA, ANBNWI-DE and NEA2+. The outcomes by the HVcMO20a and the HillVallEA18 algorithms are statistically better than those achieved by ANBNWI-DE and by NEA2+. Moreover, in the scenario of the dynamic , HillVallEA19 is significantly better than NEA2+, RS-CMSA, ANBNWI-DE and SDE-Ga, while the superiorities of HVcMO20a and HillVallEA18 over both ANBNWI-DE and SDE-Ga are significant.

Besides being the best VMO-based multimodal optimizer, these results confirm that HVcMO20a beats several prominent algorithms from the state-of-the-art, significantly in some cases. In so doing, the third research objective (the pursue of a competitive variant of VMO-N) is accomplished.

The application of statistical comparisons keeps as a research debt in the arena of multimodal optimization. The utility of the non-parametric procedures goes beyond the discovery of significant contrasts between the performances of the methods. For instance, giving the mean scores in Table 5, HVcMO20a and HillVallEA18 are equal in terms of and , while ANBNWI-DE is better than SDE-Ga in such scenarios. However, Figure 4 and Figure 5 clarify that indeed HVcMO20a is rated before HillVallEA18, and SDE-Ga is better placed than ANBNWI-DE, in view of the individual ranks of their values for every test problem, instead of the average achievements.

6.3. HVcMO20a or HillVallEA19? When to Apply Each?