Abstract

In this paper we prove that for any there exists a generic extension of , the constructible universe, in which it is true that the set of all constructible reals (here subsets of ) is equal to the set of all reals definable by a parameter free type-theoretic formula with types bounded by m, and hence the Tarski ‘definability of definable’ sentence (even in the form ) holds for this particular m. This solves an old problem of Alfred Tarski (1948). Our methods, based on the almost-disjoint forcing of Jensen and Solovay, are significant modifications and further development of the methods presented in our two previous papers in this Journal.

Keywords:

definability of definable; tarski problem; type theoretic hierarchy; generic models; almost disjoint forcing MSC:

03E15; 03E35

| Contents | ||

| 1 | Introduction | 2 |

| 1.1 The Problem................................................................................................................................................................... | 3 | |

| 1.2 Further Reformulations and Harrington’s Statement............................................................................................... | 3 | |

| 1.3 The Main Theorem........................................................................................................................................................ | 4 | |

| 1.4 Structure of the Proof.................................................................................................................................................... | 5 | |

| Flowchart.................................................................................................................................................................................. | 6 | |

| 2 | Preliminaries | 7 |

| 2.1 Definability Issues......................................................................................................................................................... | 7 | |

| 2.2 Constructibility Issues.................................................................................................................................................. | 7 | |

| 2.3 Type-Theoretic Definability vs. ∈-Definability......................................................................................................... | 8 | |

| 2.4 Reduction to the Powerset Definability...................................................................................................................... | 9 | |

| 2.5 A Useful Result in Forcing Theory............................................................................................................................. | 10 | |

| 2.6 Definable Names.......................................................................................................................................................... | 11 | |

| 2.7 Collapse Forcing........................................................................................................................................................... | 13 | |

| 3 | Almost Disjoint Forcing, Uncountable Version | 13 |

| 3.1 Introduction to almost Disjoint Forcing.................................................................................................................... | 13 | |

| 3.2 Product Almost Disjoint Forcing............................................................................................................................... | 15 | |

| 3.3 Structure of Product almost Disjoint Generic Extensions....................................................................................... | 16 | |

| 4 | The Forcing Notion and the Model | 17 |

| 4.1 Systems, Definability Aspects..................................................................................................................................... | 17 | |

| 4.2 Complete Sequences.................................................................................................................................................... | 17 | |

| 4.3 Preservation of the Completeness............................................................................................................................. | 19 | |

| 4.4 Key Definability Engine............................................................................................................................................. | 20 | |

| 4.5 We Specify ............................................................................................................................................................... | 22 | |

| 4.6 The Model.................................................................................................................................................................... | 23 | |

| 5 | Forcing Approximation | 24 |

| 5.1 Language...................................................................................................................................................................... | 25 | |

| 5.2 Forcing Approximation.............................................................................................................................................. | 26 | |

| 5.3 Consequences for the Complete Forcing Notions................................................................................................... | 27 | |

| 5.4 Truth Lemma.............................................................................................................................................................. | 27 | |

| 6 | Invariance | 28 |

| 6.1 Hidden Invariance...................................................................................................................................................... | 28 | |

| 6.2 The Invariance Theorem............................................................................................................................................. | 29 | |

| 6.3 Proof of Theorem 9 from the Invariance Theorem.................................................................................................. | 29 | |

| 6.4 The Invariance Theorem: Setup................................................................................................................................ | 30 | |

| 6.5 Transformation........................................................................................................................................................... | 30 | |

| 6.6 Finalization................................................................................................................................................................. | 32 | |

| 7 | Conclusions and Discussion | 33 |

| References | 34 | |

1. Introduction

This paper continues our research project on the issues of definability in models of set theory, that was started in [1,2,3] among other papers, and most recently in [4,5] in this Journal. Questions of definability of mathematical objects were raised in the course of discussions on the foundations of mathematics, set theory, and the axiom of choice in the early twentieth century, such as, for instance, the famous discussion between Baire, Borel, Hadamard, and Lebesgue published in Sinq lettres [6]. Various aspects of definability in models of set theory have since remained the focus of work on the foundations of mathematics, see, for example, [7,8,9,10,11,12,13] among many important recent studies.

The topic of this paper goes back to the profound research by Alfred Tarski, who demonstrated in [14] that ‘being definable’ (in most general, unrestricted sense) is not a mathematically well-defined notion (see Murawski [15] on the history of this discovery and the role of Gödel, and Addison [16] on the modern perspective of the Tarski definability theory). More specificly, restricted notions of definability, in particular, type-theoretic definability, were considered by Tarski in [17] and later work in [18].

Definition 1

(Tarski). If then is the set of all elements of order k, definable by a parameter free type-theoretic formula of order m.

Here elements of order 0 are just natural numbers (members of the set ), elements of order 1 are sets of natural numbers (commonly called reals in modern set theory), and generally, elements of order () are arbitrary sets of elements of order k (see details in Section 2.1 below). The order of a type-theoretic formula is the largest order of all its quantified and free variables. The notion of definability is taken in the form:

where the upper index routinely denotes the order of a variable or element.

1.1. The Problem

Investigating the definability properties of sets , Tarski notes in [18] that . To prove this result, one can exploit the fact that the truth of all formulas of order m can be suitably expressed by a single formula of order . Using such a formula, one easily gets . Then Tarski turns to the question whether a stronger sentence holds. Tarski comes to the following conclusion (verbatim):

the solution of the problem is (trivially) positive if ; the solution is negative if ; in the (perhaps most interesting) case the problem remains open.

The negative result for (and , to avoid trivialities) is obtained in [18] (page 110) essentially by virtue of the fact that countable ordinals admit a definable embedding into the set of all elements of order 2. This leaves:

as a major open problem in [18].

Tarski notes in [18], with a reference to Gödel’s work on constructibility [19], that it seems:

Tarski does not elaborate on this point, but it is quite clear that the axiom of constructibility (and even a weaker hypothesis, see Lemma 2 below) implies for all , and hence no proof of for even one single (the “affirmative solution” in Tarski’s words), can be maintained in . In other words, the hypothesis:

(the negative solution of (2) for all simultaneously) does not contradict the axioms. The problem of consistency of the affirmative sentences was left open in [18].

very unlikely that an affirmative solution of the problem is possible.

This paper is devoted to this problem of Alfred Tarski.

1.2. Further Reformulations and Harrington’s Statement

The problem emerged once again in the early years of forcing, especially in the case corresponding to analytic definability in second-order arithmetic. The early survey [20] by A. R. D. Mathias (the original typescript has been known to set theorists since 1968) contains Problem 3112, that requires finding a model of in which it is true that:

that is, . Recall that reals in this context mean subsets of . Another problem there, P 3110, suggests a sharper form of this statement, namely; find a model in which it is true that

that is, . The set of all constructible reals is (lightface) , and hence , so that the equality implies , that is the case of the sentence (2).

the set of analytically definable reals is analytically definable

analytically definable reals are precisely the constructible reals

Somewhat later, Problem 87 in Harvey Friedman’s survey One hundred and two problems in mathematical logic [21] requires to prove that for each n in the domain there is a model of:

For this is definitely impossible by the Shoenfield absoluteness theorem. As is the same as = all analytically definable reals, the case in (3) is just a reformulation of .

At the very end of [21], it is noted that Leo Harrington had solved problem (3) affirmatively. A similar remark, see in [20] (p. 166), a comment to P 3110. And indeed, Harrington’s handwritten notes [22] present the following major result quoted here verbatim:

Theorem 1

(Harrington [22] (p. 1)). There are models of in which the set of constructible reals is, respectively, exactly the following set of reals:

We may note that and generally for any in the context of Theorem 1. On the other hand the set of constructible reals is , and hence . Therefore Theorem 1 implies the consistency of the affirmative sentences and for any particular value , and hence shows that the Tarski problems considered are independent of .

Based on the almost-disjoint forcing tool of Jensen and Solovay [23], a sketch of a generic extension of , in which it is true that , follows in [22] (pp. 2–4). Then a few sentences are added on page 5 of [22], which explain, without much going into details, as how Harrington planned to get some other models claimed by the theorem, in particular, a model in which holds for a given (arbitrary) natural index , and a model in which , where (all analytically definable reals). This positively solves Problem 87 of [21], including the case , of course. Different cases of higher order definability are briefly observed in [22] (p. 5) as well.

Yet, for all we know, no detailed proofs have ever emerged in Harrington’s published works. An article by Harrington, entitled “Consistency and independence results in descriptive set theory”, which apparently might have contained these results among others, was announced in the References list in Peter Hinman’s book [24] (p. 462) to appear in Ann. of Math., 1978, but in fact this or a similar article has never been published in Annals of Mathematics or any other journal. Some methods sketched in [22] were later used in [25], but with respect to different questions and only in relation to the definability classes of the 2nd and 3rd projective level.

1.3. The Main Theorem

The goal of this paper is to present a complete proof of the following part of Harrington’s statement in Theorem 1, related to the consistency of the Tarski sentence and the equality , strengthened by extra claims (ii) and (iii). This is the main result of this paper.

Theorem 2.

Let . There is a generic extension of in which it is true that

- (i)

- , that is, constructible reals are precisely reals in — in particular, is a set, hence, , and even moreso,

- (ii)

- if then

- (iii)

- the general continuum hypothesis GCH holds.

Thus, for every particular , there exists a generic extension of in which the Tarski sentence holds whereas for all other values . We recall that fails in itself for all , see above.

Corollary 1.

If then the sentence is undecidable in , even in the presence of .

This paper is dedicated to the proof of Theorem 2. This will be another application of the methods sketched by Harrington and developed in detail in our previous papers [4,5] in this Journal, but here modified and further developed for the purpose of a solution to the Tarski problem.

We may note that problems of construction of models of set theory in which this or another effect is obtained at a certain prescribed definability level (not necessarily the least possible one) are considered in modern set theory, see e.g., Problem 9 in [26] (Section 9) or Problem 11 in [27] (page 209). Some results of this type have recently been obtained in set theory, namely:

- (A)

- a model [3] in which, for a given , there exists a countable non-empty set of reals, containing no OD element, while every countable set of reals contains only OD reals;

- (B)

- a model [28] in which, for a given , there is a real singleton that effectively codes a cofinal map , minimal over , while every real is constructible;

- (C)

- a model [29] in which, for a given , there exists a planar non-ROD-uniformizable lightface set, all of whose vertical cross-sections are countable, whereas all boldface sets with countable cross-sections are -uniformizable;

- (D)

- a model [30] in which, for a given , the Separation principle fails for .

Theorem 2 of this paper naturally extends this research line.

1.4. Structure of the Proof

To define a model for Theorem 2, we employ the product of two forcing notions. The first forcing is a Cohen-style collapse forcing that adjoins a generic collapse map , Section 2.7. The collapse is necessary since any model for Theorem 2 has to satisfy the inequality .

The second forcing notion has the form of the product , where each factor is an almost-disjoint type forcing determined by a set:

dense in , where and is the number we are dealing with in Theorem 2. This forcing adjoins an according system of generic sets , such that:

- (*)

- if in then covers f (that is, for unbounded-many ) iff (Lemma 15).

Basically any system of dense sets defines a similar product forcing (see Section 3.2). Forcing notions of the form satisfy certain chain and distributivity conditions in (Lemma 14), that imply some general properties of related generic extensions (Lemmas 15 and 16).

The key system is defined in Section 4.4 (Definition 6, on the base of Theorem 6 in Section 4.2), in the form of componentwise union , i.e., for all , where is the -cardinal next to , and the systems are:

- -

- Increasing, i.e., for all and ,

- -

- Small, i.e., in for all , and,

- -

- Disjoint, i.e., the components are pairwise disjoint.

We apply a diamond-based argument in Section 4 to ensure that the resulting system has its different slices () satisfying different definability and inner genericity requirements (Theorem 6 in Section 4.2), so that the descriptive complexity and the level of inner genericity (or completeness) of nth ‘slice’ tends to infinity with . This is a major novelty of the construction.

Then we consider the key product forcing notion . We extend by a collapse-generic map to , as above, and define the partial product as a forcing notion in , where:

Adjoining a -generic set G to , we get a model for Theorem 2. In particular, if , then x is definable in by means of the equivalence:

in which the implication follows from (*) via (note that since in case ), whereas the inverse implication is based on the completeness properties of the system . It also takes some effort to check that the right-hand side of (4) really defines a relation in ; for that purpose Theorem 3 is proved beforehand in Section 2.3.

To prove that, conversely, every in belongs to , we introduce forcing approximations in Section 5, a forcing-like relation used to prove the elementary equivalence theorem. Its key advantage is the invariance under some transformations, including the permutations of the index set , see Section 6.5. The actual forcing notion is absolutely not invariant under permutations of , but the -completeness property, maintained through the inductive construction of in , allows us to prove that the auxiliary forcing is in the same relation to the truth in -generic extensions, as the true -forcing relation (Theorem 10). We call this construction hidden invariance (see Section 6.1), and this is the other major novelty of this paper.

Finally, Section 6 presents the proof of the invariance theorem (Theorem 11), with the help of forcing approximations, and thereby completes the proof of Theorem 2.

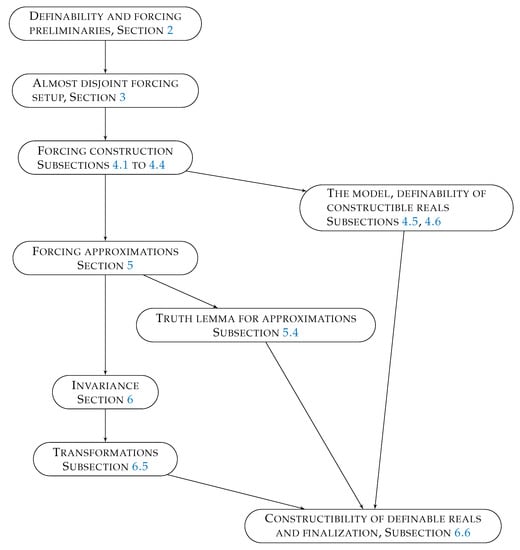

The flowchart of the proof can be seen in Figure 1 on page 6.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proof of Theorem 2.

2. Preliminaries

This Section contains several definitions and results that will be very instrumental in the proof of Theorem 2.

2.1. Definability Issues

Beginning with the type-theoretic definability, we recall some details of Tarski’s constructions from [18]. The type-theoretic language deals with variables of orders , and includes the Peano arithmetic language for order 0 and the atomic predicate ∈ of membership used as . The order of a formula is equal to the highest order of all variables in . Variables of each order k can be substituted with elements of the corresponding iteration:

of the powerset operation. In particular, (natural numbers), (the reals), (sets of reals), and so on. Accordingly each quantifier , in a type-theoretic formula is naturally relativized to , and the truth of a closed type-theoretic formula (with or without parameters) is understood in the sense of such a relativization.

If , , then, by Definition 1, is the set of all , definable in the form:

by a parameter free formula of order ; thus .

Remark 1.

We will occasionally extend the definition of to binary relations, especially in the case . Namely a set belongs to if it is definable by a parameter free formula of order with two free variables.

In matters of -definability, we refer to e.g., [31] (Part B, 5.4), or [32] (Chapter 13) on the Lévy hierarchy of ∈-formulas and definability classes , , for any transitive set H. In particular,

- = all sets , definable in H by a parameter-free formula;

- = all sets , definable in H by a formula with any sets in H as parameters.

Something like , means that only x is admitted as a parameter, while , where , means that all can be parameters. Collections like are defined similarly, and , etc. These definitions usually work with transitive sets of the form:

and is the transitive closure. In particular, , all heredidarily-countable sets.

2.2. Constructibility Issues

As usual, is the constructible universe, and will denote the Gödel wellordering of . Let be an infinite regular cardinal. The following are well-known facts in the theory of constructibility, see e.g., [33] and Lemma 6.3 ff in [31] (Section B.5):

- 1°.

- The set belongs to and is equal to .

- 2°.

- The restriction is a wellordering of of length and a relation.

- 3°.

- On the other hand, the set and relation belong to and to .

- 4°.

- The map is as well.

The last statement implies the following useful definability estimation.

- 5°.

- Assume that and is . If , then let be the -least witness. Then is as well.

Indeed is equivalent to , where:

and the bounded quantifiers do not influence the definability class.

We proceed with several easy and rather known lemmas.

Lemma 1.

Assume that and . Then , and hence if , , or , then , resp., as well.

Proof.

By the Shoenfield absoluteness, it suffices to prove that is true in .

We argue in . Let , so that (hereditarily countable). The set:

belongs to by 4° since:

Let be the -least f such that ; then is by 5°. It follows that is (with x as the only parameter). Therefore, as , we have because for some n. It follows that . (See e.g., [34] (p. 281) on this translation result.) □

Remark 2

(Essentially Tarski [18]). If and then .

Proof.

If then the set is uncountable. On the other hand is countable, hence . Note that by 3° above. It follows that if then Z belongs to , too, and then the -least element of the set Z belongs to because is on Y still by 3°. However by construction. This is a contradiction. □

Lemma 2.

If and , then .

Proof.

We have since . Therefore . If, to the contrary, , then the set belongs to as well since by 3° above. We conclude that the -least element belongs to , because is on Y by 3°. This is a contradiction since by construction. □

2.3. Type-Theoretic Definability vs. -Definability

It occurs that the definability classes in sets of the form correspond to the Tarski definability classes, in the sense of the following theorem:

Theorem 3.

Assume that the generalized continuum hypothesis holds for all infinite cardinals . If and , then x is if x is -definable in .

In case (then and the GCH premice is vacuous), this result was explicitly mentioned, in [34] (p. 281), a detailed proof see e.g., [32] (Lemma 25.25).

Proof.

The GCH premice of the theorem is equivalent to . This implies : if then x is surely -definable in .

The inverse implication takes more effort. We have to somehow model the -structure of in . For this purpose, if and then define a quasi-pair by induction as follows. If , so that , then put . If then put . Note that elements and belong to every type-theoretic level . It can be easily established by induction that if and then and .

Following [32] (25.13), we associate, with each , a binary relation defined so that:

on the set . Let contain all sets such that is an extensional well-founded relation on , with the additional property that 0 is the only top element of , that is, holds for no . If then let be the unique 1-1 map defined on and satisfying for all — the transitive collapse. We put .

Under our assumptions, F is a map from onto , -definable in .

One easily proves that belongs to , that is, it is type-theoretically definable with quantifiers only over order levels . Moreover the binary relations , defined on by:

belong to as well. Namely, let a bisimulation for be any binary relation satisfying and, for all and ,

Then, on the one hand, iff there exists a bisimulation for iff there exists such that is a bisimulation for . On the other hand, we can express the property “ is a bisimulation for ” by a type-theoretic formula with quantifiers only over orders , by suitably replacing pairs with quasipairs .

To treat , we have to only change above to .

Finally if then let , so that and .

And now let be -definable in by a parameter free formula . Then we have , where is obtained from by substitution of for = and for ∈ and relativization of all quantifiers to . This proves . □

2.4. Reduction to the Powerset Definability

Let ≼ be the wellordering of defined so that iff:

lexicographically. Let be the order preserving map: iff —the canonical pairing function. Let and be the inverse functions, so that for all .

Lemma 3

(routine). If is an infinite cardinal and , then 𝕡 maps onto bijectively, and the restriction is constructible and .

Now we prove another reduction-type definability theorem.

Theorem 4.

If is a regular cardinal, , , and X is -definable in with Y as the only parameter, then X is -definable in the structure with Y as the only parameter.

Proof (sketch).

If then let be a binary relation on its domain . Following the proof of Theorem 3, let contain all sets such that is an extensional well-founded relation on , with the additional property that and 0 is the only top element of , that is, holds for no . If then let be the unique 1-1 map defined on and satisfying for all —the transitive collapse. We put ; is a map from onto , -definable in .

Both and the binary relations , defined on by:

are -definable in by the same bisimulation argument as in the proof of Theorem 3. Finally if then let , so that and .

Now let be -definable in by a formula . Then we have , where is obtained from by the substitution of for = and for ∈ and relativization of all quantifiers to . This proves the theorem. □

2.5. A Useful Result in Forcing Theory

We remind that, by [32] (Chapter 15), if is an infinite ordinal, then a forcing notion :

- Is -closed, if any -decreasing sequence in P, of length , has a lower bound in P;

- Is -distributive, if the intersection of -many open dense sets is open dense, and a set is open, iff , and dense, iff for any there is , .

- Satisfies -chain condition, or -CC, if every antichain has cardinality strictly less than

We will make use of the following general result in forcing theory.

Lemma 4.

Assume that, in , are regular infinite cardinals, and are forcing notions, Q satisfies Ω-CC in , and P is ϑ-closed in . Assume that is a pair -generic over . Then,

- (i)

- P remains ϑ-distributive in ,

- (ii)

- Ω is still a cardinal in ,

- (iii)

- Every set , , bounded in Ω, belongs to .

Proof.

(i) Consider any sequence in of open dense sets . Prove that their intersection is dense. Let . Then belongs to . Therefore there is a name , , satisfying . Then for all , where . There exists a condition which -forces

- (A)

- “ is open dense in P”

over for every . We can w.l.o.g. assume that forces (A), otherwise replace Q by . Under this assumption, we have the following:

- (B)

- If , , and then there exist and such that , , and -forces over .

Now we prove a stronger fact:

- (C)

- If and , then there is , , such that forces over .

Indeed, arguing in , and using (B) and the assumption that P is -closed, we can define a decreasing sequence of conditions in P, where , and a sequence of conditions in Q, such that , is incompatible with whenever , and each -forces . Note that the construction really has to stop at some otherwise we have an antichain in Q of cardinality . Thus is a maximal antichain, and on the other hand, as P is -closed and , there is a condition satisfying for all . Then every -forces by construction, therefore, as A is a maximal antichain, q witnesses (C).

To accomplish the proof of (i), we define, using (C), a decreasing sequence of conditions in P, such that and, for any , forces over . Once again, there is a condition , for all . Then forces for all , hence , as required.

Finally, as Q is -CC in , remains a cardinal in . Then, as P is -distributive in , we obtain (ii) and (iii) by standard arguments. □

2.6. Definable Names

Let be any forcing notion. It is well known (see, e.g., Lemma 2.5 in Chapter B.4 of [31]) that if is a -generic filter over , , and , , then there is a set , , such that:

such a t is called a Q-name (for Y), whereas is the -valuation, or -interpretation of t. There is a more comprehensive system of names and valuations, which involves all sets Y in generic extensions, not only those included in the groung model, see e.g., Chapter IV in [35], but it will not be used in this paper. The next theorem claims that in certain cases such a name t as above can be chosen of nearly the same definability level as the set Y itself.

Theorem 5.

Assume that is any forcing, is -generic over , is a cardinal in (hence, in , too), , , , and , . Then,

- (i)

- If Y belongs to (hence to ), then Y also belongs to

- (ii)

- If and Y belongs to (meaning in with arbitrary definability parameters in allowed) then there exists a name , , such that

Proof.

To prove (i) note that . But the formula “x is contructible” is [31] (Part B, 5.4). It follows that H is . Now the result is clear: We formally relativize, to the set H, all quantifiers in the definition of Y in H, getting a definition of Y in .

To prove (ii), assume that . We utilize a more complex system of representation of sets in , affecting all these sets, not just subsets of sets in . We take it from [36]. Inductively on the -rank , each set a is mapped to the set (depends on F!). The next lemma continues the proof of Theorem 5.

Lemma 5.

.

Proof.

From right to left, an elementary induction argument works. Prove it from left to right. Induction by the -rank , for each we define a set such that . If , then will do. Assume that and is already defined for each . The set , has cardinality in . Moreover, there is a set , , of cardinality in , such that . (Indeed, has cardinality in . Let be a constructible enumeration of elements of H. As strictly, there is such that . The set B is as required.)

According to the above, we have for some , . Then . On the other hand, it is easy to check that , that is, you can take . This ends the proof of the lemma. □

In continuation of the proof of Theorem 5(ii), we introduce, following [36], the forcing relation (where ) by induction on the logical complexity of the formula (a closed formula with parameters in H); it corresponds to as a Q-generic extension of H. Below ⩽ is the partial order on Q, and means that q is a stronger condition.

- (I)

- iff ;

- (II)

- iff or ;

- (III)

- iff ;

- (IV)

- iff or ;

- (V)

- iff ;

- (VI)

- iff .

This definition assumes that some logical connectives are expressed in a certain way via other connectives. For each parameter free formula , define a set:

Lemma 6.

If and φ is a formula, then is (Q is allowed as a sole parameter).

Proof.

All quantifiers of definitions (I)–(V) are bounded either by the set , or by a set of the form , where still . Therefore it is not difficult to show that for any bounded formula . (The sole unbounded quantifier will express the existence of a full description of all subformulas of the form , , that appear in accordance with (I)–(III).) Induction on k proves the result. □

The next lemma is similar to the Truth Lemma as in [36], so the proof is omitted.

Lemma 7.

Let Φ be a closed formula with parameters in H, and obtained from Φ so that each is replaced by . Then is true in iff there exists such that .

Let us finish the proof of Theorem 5(ii). Let , . There is a parameter free formula , and a parameter , such that . For each , we define the set by induction, so that , and if then . Then for all x. It follows by Lemma 7 that:

where is such that (exists by Lemma 5), whereas:

Finally, note that the function belongs to . We conclude that by Lemma 6, as required. This completes the proof of Theorem 5. □

2.7. Collapse Forcing

We conclude from Lemma 2 that the construction of any generic extension of , in which holds for some , has to involve a collapse of down to , explicitly or implicitly. To set up such a collapse in a technically convenient form, we let be the set of all constructible sets , and let . Thus is the ordinary Cohen-style collapse forcing that makes (and as well) countable in -generic extensions. The choice of as the collapse domain, instead of , is made by technical reasons that will be clear below. Note that adjoins generic maps to . A map is -generic over iff the set is -generic in the usual sense.

Lemma 8

(Routine). If is -generic over then for all .

The representation result, as in the beginning of Section 2.6, takes the following form: If is -generic over , , and , , then there is a set , , such that:

such a t is called a -name (for Y).

Theorem 5 is applicable for and any -cardinal , whereas if , , then Lemma 4 is applicable for , , , and any forcing , -complete in .

3. Almost Disjoint Forcing, Uncountable Version

Here we introduce the main coding tool used in the proof of Theorem 2, an uncountable version of almost disjoint forcing of Jensen–Solovay [23].

3.1. Introduction to almost Disjoint Forcing

Definition 2.

Fix an uncountable successor -cardinal . The value of Ω will be specified in Section 4.5 with respect to the integer of Theorem 2, namely, , but until then we will view Ω as an arbitrary successor -cardinal.

We put and . Here , resp., mean the next, resp., previous -cardinal, which may not be true cardinals in generic extensions of .

We finally put:

Moreover if is a generic extension of then we define:

provided remains a cardinal in .

- Let , the set of all constructible non-empty sequences s of ordinals , of length , called strings. We underline that , and , the empty string, does not belong to ;

- Let = all constructible -sequences of ordinals ; ;

- If then put ,a tree in , without terminal nodes;

- A set is dense iff , i. e. for any there is such that ;

- If then let . If is unbounded in then say that S covers f, otherwise S does not cover f.

Definition 3

(in ). is the set of all pairs of sets , of cardinality strictly less than Ω in . Elements of will be called (forcing) conditions.

If then ; a condition in .

Let . Define (q is stronger as a forcing condition) iff , and the difference does not intersect , that is, . Here .

Lemma 9

(in ). The sets , , belong to and while in .

Clearly iff , and .

Lemma 10

(in ). Conditions are compatible in iff does not intersect , and does not intersect . Therefore any are compatible in iff and .

Proof.

If (1), (2) hold then and , thus are compatible. □

If then put . Thus if then .

Any conditions are compatible in iff they are compatible in iff satisfies both and . Thus we say that conditions are compatible (or incompatible) without an indication which set containing is considered.

Lemma 11

(in ). Let . Then it is true in that , and the forcing notion satisfies -CC, and is -closed, hence -distributive. Moreover satisfies -CC in any generic extension of , in which remains a cardinal.

Proof.

The closed/distributive claim is obvious on the base of the cardinality restrictions in Definition 3. To prove the -CC claim, argue in . If belong to an antichain then by Lemma 10. Let all subsets , , with in . Then M is a set of cardinality in , hence in as well. □

If in , and is a -generic set, then put ; thus . The next lemma witnesses that forcing notions of the form belong to the type of almost disjoint (AD, for brevity) forcing, invented in [23] (§ 5).

Lemma 12.

Suppose that, in , is dense. Let be a set -generic over . Then:

- (i)

- If in then does not cover

- (ii)

- , hence

Proof.

(i) Let . The set is dense in . (Let . Define so that and . Then and .) Therefore . Pick any . Then . Now every is compatible with p, and hence by Lemma 10. Thus is bounded in . Let . If then the set is dense in . (If then . As , there is , , with . Define p so that and . Then and .) Let . Then . As is arbitrary, is unbounded.

(ii) Consider any . Suppose . Then . If there exists then by definition we have for some . However, then are incompatible by Lemma 10, a contradiction. Now suppose . Then there exists incompatible with p. By Lemma 10, there are two cases. First, there exists . Then , so p is not compatible with . Second, there exists . Then any condition satisfies . Therefore , so , and p is not compatible with . □

3.2. Product Almost Disjoint Forcing

Arguing under the assumptions and notation of Definition 2, we consider , the cartesian product, as the index set for a product forcing.

Definition 4

(in ). (note the boldface upright form) is the -product of copies of (Definition 3 in Section 3.1), ordered componentwise: (p is stronger) iff in for all .

That is, and consists of all maps , . If then put and for all , so that , where and are arbitrary, and means all subsets of cardinality strictly.

- Note that, unlike product almost-disjoint forcing notions developed in [4,5], is not a finite-support product;

- If then we define and

- If then define by , in the sense of Definition 3 in Section 3.1, for all .

Lemma 13.

Conditions are compatible in iff and .

Let an -system be any map , such that each set is empty or dense in . In this case, let

- If U is an -system then is the -product of the sets , .

Lemma 14

(in ). Let U be an -system. Then it is true in that , and the forcing notion is -closed, hence -distributive, and satisfies -CC, and the product satisfies -CC as well. Moreover satisfies -CC in any generic extension of in which remains a cardinal.

Proof.

The closed/distributive claims follow from Lemma 11. To prove the antichain claim we observe that if satisfy then are compatible. However the set has cardinality in as it consists of all functions . To extend the result to the product , note that . □

Definition 5.

Suppose that . If then define to be the usual restriction, so that and for all . A special case: If then let , where . If U is an -system then define to be the ordinary restriction as well. Furthermore, if then define:

Q ⊆ *PΩ Q ↾ z = {p ↾ z : p ∈ Q}; Q ↾ z ⊆*PΩ ↾ z. Q = P[U], U ∈ L -system, and then we get P[U] ↾ z = {p ↾ z : p ∈ P[U]}, P[U] ↾ ≠⟨n,i⟩, P[U] ↾ ≥m, .

Remark 3.

Suppose that in Definition 5. If , then can be identified with a condition such that and for all . For instance, this applies w.r.t. , , , .

With such an identification, we have , and for (in case ).

However, if then such an identification fails. This is a consequence of our deviation from the finite-support product approach taken in [4,5], which would not work in the setting of this paper.

The same applies for the restrictions of -systems U.

3.3. Structure of Product almost Disjoint Generic Extensions

Arguing under the assumptions and notation of Definition 2, we let U be an -system in . Consider as a forcing notion. We will study -generic extensions of the ground universe . Define some elements of these extensions. Suppose that is a generic set. Let,

where ; thus and splits into the family of sets . This defines a sequence of subsets of .

If then let .If then can be identified with .

Put .

Lemma 15.

Let U be an -system in , and be a set -generic over . Then:

- (i)

- (ii)

- If then the set is -generic over , hence if then does not cover

- (iii)

- If , is bounded, then

- (iv)

- All -cardinals are preserved in , and GCH holds in

Proof.

To prove (i) apply Lemma 12(ii).

The genericity in (ii) holds by the product forcing theorem, then use Lemma 12(i).

Claim (iii) follows from the -closure claim of Lemma 14.

(iv) We conclude from (iii) that all -cardinals remain cardinals in , and GCH holds for all -cardinals strictly. It follows from the -CC claim of Lemma 14 that all -cardinals remain cardinals in , and since in , GCH holds for all of them in . And finally we still have in since by (i) the model is an extension of by adjoining a subset of obtained by a suitable wrapping of . □

The next lemma is useful in dealing with combined -generic extensions of , where, by the product forcing theorem, is -generic over and G is -generic over , or equivalently, G is -generic over and is -generic over .

Lemma 16.

Let U be an -system in , and a pair is -generic over . Then:

- (i)

- All -cardinals are preserved in , so that for all

- (ii)

- GCH holds in

- (iii)

- If and , is bounded, then

- (iv)

- If and , then and .

Note that Claims (iii), (iv) are not applicable in case .

Proof.

To prove (i), (ii) recall that all -cardinals remain cardinals in , and GCH holds in , by Lemma 15(iv). It remains to note that is -generic over and make use of Lemma 8. To prove (iii) apply Lemma 4 with , , . Note that in case .

Finally Claim (iv) is a routine corollary of (i)–(iii). □

4. The Forcing Notion and the Model

In this Section, we prove Theorem 2 on the base of another result, Theorem 8, see Remark 4 on page 23. The proof of Theorem 8 will follow in the remainder of the paper. The structure of the extension will be presented in Section 4.6, after the definition of the forcing notion involved in Section 4.5. Recall that the -cardinals:

were introduced by Definition 2 on page 13. They remain to be fixed until Section 4.5, where their value will be specified in terms of the number we are dealing with in Theorem 2.

4.1. Systems, Definability Aspects

We argue in under the assumptions and notation of Definition 2 on page 13.

In continuation of our notation related to -systems in Section 3.2, define the following.

- An -system U is small, if each has cardinality in ;

- An -system U is disjoint if whenever ;

- If are -systems and for all , then V extends U, in symbol ;

- If is a sequence of -systems then the limit -system is defined by , for all .

Let (disjoint systems) be the set of all disjoint -systems, and let (small disjoint systems) be the set of all small disjoint -systems .

Define , and similarly etc. by Definition 5.

The sets , , , etc., and the order relation ≼, belong to , of course. Recall that, by (5),

Lemma 17

(in ). The following sets belong to and to , , , , , , , the set , the relation ≼.

Proof.

All these sets have rather straightforward definitions, with as the only parameter. To eliminate , it suffices to prove that . Note first of all that “ is a cardinal (initial ordinal)” is a formula:

On the other hand, is the largest cardinal in , hence it holds in that:

We conclude that . Finally, the conversion is routine. □

4.2. Complete Sequences

We prove a major theorem (Theorem 6) in this Subsection. It deals with -increasing transfinite sequences in , satisfying some genericity/definability requirements. This is similar to some constructions in [4] and especially in [5] (Theorem 3). Yet there is a principal difference. Here the notion of extension ≼ is just the componentwise set theoretic extension, unlike [4,5], and originally [23], where the extension method was designed so that increments had to be finitewise Cohen-style generic over associated transitive models of a certain fragment of . Here the only restriction is that extensions have to obey the disjointness condition as defined in Section 4.1. In other words, if are -systems in , then, beside , the increments have to be pairwise disjoint and each to be disjoint with the union .

Such a simplification is made possible here largely because the definability classes of the form depend only on the highest quantifier order and do not depend on the number and type of the quantifiers involved in the definition of the set considered—unlike e.g., [5], where we dealt with the definability classes , which obviously depend on the number of the quantifiers involved.

We begin with an auxiliary lemma.

Recall that, by (5),

Lemma 18

(in ). Under the assumptions and notation of Definition 2, for any there exist , , and such that the sequences , , belong to and, if , , and is a -increasing continuous sequence of -systems in , then any closed unbounded set contains an ordinal such that .

Proof.

We argue in , that is, under the assumption of , the axiom of constructibility. It is known that the diamond principle holds in for any regular cardinal , in particular, for , see, e.g., Theorem 13.21 and page 442 in [32]. The principle asserts that there is a sequence of sets , of definability class , and such that:

- (*)

- If and is a closed unbounded set then there is such that .

Let be any bijection. Put . Clearly is still a sequence. Moreover the following is true:

- (†)

- If is a sequence of sets in and is a closed unbounded set then there is with .

Using the sets , we accomplish the proof of the lemma as follows. Assume that . If is a sequence of the form , such that each is a triple , where both and do not depend on whereas for each and is a -increasing and continuous sequence, then put , and . Otherwise put and let be the null -system, that is, for all . It follows from (†) (plus a routine analysis of definability based on Lemma 17) that this construction leads to the result required. □

Theorem 6

(in ). Under the assumptions and notation of Definition 2, there is a -increasing sequence of -systems in , such that:

- (i)

- The sequence is continuous, so that for all limit ordinals

- (ii)

- If then the “slice” is ;

- (iii)

- If then the “tail” is -complete, in the sense that for any set there is such that the -system -solvesD, i.e.,

- -

- either

- -

- or there is no -system with

- (iv)

- There is a recursive sequence of parameter free -formulas such that if and then iff .

Here the “slice” of a system U is essentially equal to the “column” of the whole “matrix” , while the “tail” can be viewed in the union of all columns to the right of m inclusively, see Definition 5.

Proof.

We argue in . One of the difficulties here is that we have to account for different levels of genericity and completeness for different slices of the construction. To cope with this issue, we make use of Lemma 18. Let us fix the sequences of terms such as in the lemma.

Let be Gödel’s wellordering of , as in Section 2.2.

For any , let be a fixed universal set, that is, itself is , and if is (parameters in allowed), then there is such that . If and , then let be the -least -system in satisfying and:

- (a)

- , and

- (b)

- The -system -solves the set .

Making use of 5° of Section 2.2, we conclude that the sequence is .

Now we define a sequence of -systems , as required by Theorem 6, by induction.

Put for all .

If is the limit then by (i) define .

Suppose that a -system is defined, and the goal is to define the next one . Fix and define the components . Note that this definition will depend on the components (with the same ) only, but not on the -system as a whole.

If it is true that:

(where is the -system given by Lemma 18), then put and . Otherwise, i.e., if (7) fails, just keep it with .

We assert that this inductive construction of -systems leads to Theorem 6.

Requirement (i) of the theorem is satisfied by construction.

The definability requirement (ii) of the theorem is subject to routine verification on the base of Lemma 17, which we leave to the reader.

To prove (iii), fix a number m and a set . We have to find an index such that the -system -solves D. There is an element satisfying:

where is the universal set as above. Pick, by Lemma 18, an ordinal satisfying . Then (7) holds for all , and hence by definition we have . Therefore the -system -solves the set D by (b), as required.

(iv) Coming back to the choice of universal sets in (b), it can be w.l.o.g. assumed that there is a recursive sequence of parameter free -formulas such that each is a formula and . This routinely leads to -formulas required. It can be observed that in fact each is a formula (not important and will not be used).

This completes the proof of Theorem 6. □

4.3. Preservation of the Completeness

The next lemma says that the completeness property (iii) of Theorem 6, of the sequence , still holds, to some extent, in rather mild generic extensions of .

Lemma 19.

Under the assumptions and notation of Definition 2, suppose that is a -increasing sequence of -systems in satisfying (i)–(iv) of Theorem 6.

Let be a forcing notion with in , e.g., . Let be a set -generic over .

Assume that , , and a set , , belongs to , and is open in so that any extension of a -system in belongs to D itself.

Then there is an ordinal α, , such that -solvesD, as in Theorem 6(iii).

Proof.

As obviously , we conclude by Theorem 5(ii) that there is a name , , such that .

We argue in . If , , and there is such a condition that (meaning h is stronger) and , then write . If then we define:

Each of the sets belongs to by virtue of Lemma 17 and the choice of t. Therefore, by the choice of the sequence of -systems, for every there is an ordinal , , such that the -system -solves the set .

Note that by the cardinality argument.

We claim that the -system -solves D. It suffices to prove that if a -system extends , then the -system itself belongs to D. Moreover, as D is open, it suffices to find , satisfying .

We argue in . Consider the set . If then pick a particular such that and holds. If then put . The set is dense in Q. It follows that there is . On the other hand, as , there is a condition with .

Then there exists some satisfying and . This implies . It follows, by the choice of , that , too. However then , and hence we have . By definition there is a condition with , such that However (since ). We conclude that , as required. □

4.4. Key Definability Engine

We argue under the assumptions and notation of Definition 2 on page 13. In particular, a successor -cardinal is fixed. We make the following arrangements.

Definition 6

(in ). We fix a -increasing sequence of -systems satisfying conditions (i)–(iv) of Theorem 6 for the particular -cardinal Ω introduced by Definition 2.

We define the limit -system , the basic forcing notion , and the subforcings , .

Define restrictions , (, ), etc. as in Section 3.2.

Thus by construction is the -product of sets . Lemma 14 implies some cardinal characterictics of , namely:

- (I)

- in ,

- (II)

- satisfies -CC in ,

- (III)

- is -closed and -distributive in .

Corollary 2.

does not adjoin new reals to .

Proof.

The result follows from (III) because by Definition 2. □

As for definability, the set is not parameter free definable in , yet its slices are:

Lemma 20

(in ). Let . Then the set belongs to . In addition there is a recursive sequence of parameter free -formulas such that, for any , if and then iff .

Proof.

To prove the first claim, apply (ii) of Theorem 6. To prove the additional claim define:

where are formulas given by (iv) of Theorem 6. □

We further let formulas () be defined as follows:

The next theorem shows that any real in and even in some generic extensions of can be made parameter free definable in appropriate subextensions of -generic extensions, basically by means of the formulas . We prove this result in a rather general form, which includes the case of a forcing notion , actually used in this paper, as just a particular case. The proof of the particular case would not be any simpler though.

Theorem 7.

Assume that is a forcing notion, in , a pair is -generic over , , and . Then,

- (i)

- is a cardinal in

- (ii)

- If then and holds, but

- (iii)

- If then and moreover there is no set in such that .

- (iv)

- It follows that in

- (v)

- If then the -th slice belongs to , where

- (vi)

- If , , and GCH holds in for all cardinals , then it holds in that for all

- (vii)

- Under the assumptions of (vi), it holds in that the set z as a whole belongs to .

Proof.

(i) remains a cardinal in by Lemma 15(iv), hence Q still satisfies in . As W is -generic over , remains a cardinal in and in .

(ii) If then by construction:

and hence as well. Now follows from Lemma 15(ii).

(iii) We w.l.o.g. assume that and . Then can be identified with , see Remark 3. Suppose towards the contrary that satisfies . There is a name , , such that:

The forcing remains -CC in by Lemma 14. This allows us to w.l.o.g. assume that in , and then .

There is a condition which -forces over . If then put ; .

We argue in . As , there is an ordinal such that and . Consider the set D of all -systems extending and such that there exists a condition , , an element , and an ordinal , such that contradicts to every . Then D is by Lemma 17 (and Theorem 5(i), to transfer the definability properties from to ), with as a parameter. Therefore, by Lemma 19, there is an ordinal such that the pair -solves D as in Theorem 6(iii). We have two cases.

Case 1: . Let this be witnessed by as indicated. Then , therefore . By definition , hence . Furthermore, if , , then the condition -forces over . We conclude that forces over . Note that forces because . However . This is a contradiction.

Case 2: There is no -system extending . We can assume that , since if then the -system has the same property. Easily there exists , such that . (To prove this claim note that the set of all -systems satisfying is dense in therefore, any U that -solves belongs to .)

Take any . Then , and hence forces over by the choice of . It follows that there exists a condition , , and an ordinal , such that for any , forces over , where . Thus contradicts to each condition . We may w.l.o.g. assume that (otherwise increase appropriately). Under these assumptions, define a -system U so that:

and for all pairs of indices other than and . Obviously U extends , and . Therefore . But this contradicts the Case 2 hypothesis.

Claim (iv) is an immediate corollary of (ii) and (iii).

To prove (v), note that (*) by (iv). However with n fixed the relation with as arguments is by Lemma 20, hence by Theorem 5(i). Now follows by (*).

To prove (vi), make use of (v) and Theorem 3.

Let us finally prove (vii). Detalizing the proof of (v) and (vi) on the base of formulas of Lemma 20, we obtain a recursive sequence of parameter free -formulas such that if then iff . The proof of Theorem 3 is obviously effective enough to obtain another recursive sequence of parameter free type-theoretic formulas of order such that it holds in that: iff , that is, .

However it is known that the truth of formulas of order can be uniformly expressed by a suitable formula of order , see e.g., [18]. In other words, there is a parameter free type theoretic formula of order such that it holds in that: iff , that is, . We conclude that z is definable in by a type-theoretic formula of order . In other words, in , as required. □

4.5. We Specify

We come back to Theorem 2. Now it is time to specify the value of the -cardinal , so far left rather arbitrary by Definition 2 on page 13.

Definition 7

(in ). Recall that is a number considered in Theorem 2.

We let , and accordingly define , ,

by Definition 2. Applying Definition 6 with , we accordingly fix:

- -

- A -increasing sequence of -systems satisfying (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) of Theorem 6 for the chosen -cardinal ,

- -

- The limit -system ,

- -

- The basic forcing notion , and the subforcings , ,

and define restrictions (), , , etc. as in Section 3.2.

4.6. The Model

To prove Theorem 2 we make use of a certain submodel of a -generic extension of . First of all, if is any function then we put:

Now consider a pair , -generic over . Thus is a generic collapse function, while the set is -generic over . The set:

obviously belongs to the model , but not to . Therefore the restrictions , in the next theorem have to be understood in the sense of Definition 5 on page 15, ignoring Remark 3 since, definitely . Thus is a forcing notion in , not in .

The following theorem describes the structure of such generic models.

Theorem 8.

Under the assumptions of Definition 7, let a pair be -generic over . Then:

- (i)

- is a set -generic over ,

- (ii)

- for all ordinals , in particular,

and it is true in the model that

- (iii)

- If then and , whereas if then

- (iv)

- GCH holds;

- (v)

- Every constructible real belongs to ,

- (vi)

- If and then , and

- (vii)

- every real in is constructible.

Remark 4.

Theorem 8 implies Theorem 2 via the model , of course. As for Theorem 8 itself, its proof follows below in this paper. Claims (i)–(vi) will be established right now, and Claim (vii) is accomplished in Section 6.6, based on the substantial work in Section 5 and Section 6.

Proof

(Claims (i)–(vi) of Theorem 8). To prove that is -generic over , note that is -generic over by the product forcing theorem w.r.t. the product . However can be naturally identified with the product in , where . This implies the result by another application of the product forcing theorem.

To establish (ii), (iii), and (iv), it suffices to apply Lemma 16, as .

To prove Claim (v), let . By the genericity of , there is a number such that . Then, for any i, we have iff . By Theorem 7(vi) (with , , , ), it is true in that x belongs to , as required.

To prove Claim (vi), assume that and ; we have to show that in . We have two cases.

Case 1: . Consider the set defined by (9) in Section 4.6. By definition , . It follows from Theorem 7(vii) (with , , , ), that , hence as . Now suppose to the contrary that in . As , there exist real , , which do not belong to ; let be the least of them in the sense of the Gödel well ordering of . Then itself belongs to by 5° of Section 2.2, since so does z by the above, which is a contradiction.

Case 2: . It suffices to apply Lemma 2 on page 8 because and holds in by Claims (v) and (vii). We may note that this short argument refers to Claim (vii) that will be conclusively established only in Section 6.6.

An independent proof is as follows. If , then , and hence Theorem 8(iii) implies:

We conclude that the sets and are the same in these models, and hence it suffices to prove that in the -generic extension . Now we apply the fact that collapse forcing notions similar to are homogeneous enough for any parameter free formula either be forced by every condition, or be negated by every condition. In our case, it follows that and is countable in . Therefore if, to the contrary, in , then taking the Gödel-least in , we routinely get in via 5° of Section 2.2, with a contradiction.

This completes the proof of Claims (i)–(vi) of Theorem 8. □

5. Forcing Approximation

We argue under the assumptions and notation of Definition 7 on page 22.

Beginning here a lengthy proof of Claim (vii) of Theorem 8, our plan will be to establish the following, somewhat unexpected result. Recall that, by Theorem 8(ii), it is true in that and in case , whereas in case .

Theorem 9.

Assume that a pair is -generic over , and , , and it is true in that:

- either

- or

- and a is -definable in .

Then .

Remark 5.

Theorem 9 implies Claim (vii) of Theorem 8.

Indeed, arguing in , suppose that , . If then we immediately have the “or” case of Theorem 9. Thus suppose that . Theorem 3 is applicable by Theorem 8(iv), therefore x is -definable in , that is, in by Theorem 8(iii). Then Theorem 4 is applicable as well, and hence we have the “either” case of Theorem 9. We conclude that by Theorem 9. However, by Lemma 14, the forcing notion is -closed in , and this property is sufficient for -generic sets not to add new subsets of ω, so , as required by (vii) of Theorem 8.

Thus Theorem 9 completes the proof of Theorem 8 as a whole because other claims of Theorem 8 have been already established, see Section 4.6.

To prove Theorem 9, we are going to define a forcing-like relation similar to approximate forcing relations considered in [4,5], and earlier in [3] and some other papers on the base of forcing notions not of an almost-disjoint type. Then we exploit certain symmetries of objects related to .

Definition 8.

Extending Definition 7 on page 22, let us fix a pair , -generic over for the remainder of the text. We consider generic extensions:

We shall assume that (the “either” case of Theorem 9). The “or” case is pretty similar: Ω is changed to ω during the course of the proof.

5.1. Language

We argue under the assumptions and notation of Definitions 7 and 8.

- Assume that , . Then let be the set of all sets , , with in .

Note that , a bigger forcing notion, is used instead of in this definition. One of the advantages is that is -definable in by Lemma 17.

If and then put .

Lemma 21.

.

Proof.

Let , . The set is -generic over by the product forcing theory. Therefore, by a well-known property of generic extensions (see, e.g., [32]), there is a name , , such that . To reduce t to a name with the same property, satisfying , apply Lemma 14. □

Now, arguing in , we introduce a language that will help us to study analytic definability in the generic extensions considered. We argue under the assumptions and notation of Definition 8.

Let be the 2nd order language, with variables , assumed to vary over ordinals , and , varying over the subsets of . Atomic formulas of the following types are allowed:

(See Section 2.4 on 𝕡.) Only the connectives ∧ and ¬ and quantifiers and are allowed, the other connectives and are treated as shortcuts, and, to reduce the number of cases, the equality will be treated as a shortcut for .

The complexity of an -formula is defined by induction so that:

- for all atomic formulas,

- ,

- and ,

- Finally, .

Note that the complexity of quantifier-free formulas can be as high as one wants.

If , , then let be the extension of by:

- -

- Ordinals to substitute variables over ,

- -

- Names in to substitute variables over .

If , then the valuation of such a formula is defined by substitution of for any name that occurs in , and relativizing each quantifier or to resp. , . Thus is a formula of with parameters in and quantifiers relativized as above, that is, to and to , and can contain 𝕡 interpreted as . (See Section 2.4 on 𝕡.)

5.2. Forcing Approximation

We still argue under the assumptions and notation of Definitions 7 and 8.

Our next goal is to define, in , a forcing-style relation . In case and , the relation will be compatible with the truth in the model , viewed as a -generic extension of . But, perhaps unlike the true forcing relation associated with , the relation will be invariant under certain transformations.

The definition goes on in by induction on the complexity of .

- (F1)

- When writing , it will always be assumed that , , , , is a closed formula in .

- (F2)

- If , , , , and , then: iff in fact , and the same for the formulas and .

- (F3)

- If are as above, , , then: iff there exists a condition such that and .

- (F4)

- If are as above, then: iff and .

- (F5)

- If are as above, then iff there is such that .

- (F6)

- If are as above, then iff there exists a name such that .

We precede the last item with another definition. If then let be the set of all -systems such that for some . Thus .

- (F8)

- If are as in (F1), is a closed formula, , then iff there is no -system extending U, and no , , such that .

Lemma 22

(in ). Let satisfy (F1) above. Then:

- (i)

- If , extends U, and , then ;

- (ii)

- If , , and , then fails.

Proof.

The proof of (i) by straightforward induction is elementary. As for (ii), make use of (F8). □

Now let us evaluate the complexity of the relation . Given a parameter free -formula with any set of free variables allowed in , we define, in , the set:

Lemma 23

(in ). If φ is a parameter free -formula and , then is .

Proof.

The set is by Lemma 17, and hence as well by Theorem 5(i) in Section 2.6. The relations with arguments resp. , are routinely checked to be , too. (Note that bounded quantifiers preserve .) After this remark, prove the lemma by induction on the structure of .

The case of atomic formulas of type (F2) is immediately clear. (The pairing function in (F2) is by Lemma 3.) The result for atomic formulas of type (F3) amounts to the formula , which is by the above. The step (F4) amounts to the intersection of two sets is quite obvious. And so are steps (F5) and (F6) (a -quantification on the top of a given ).

To carry out the step (F8), note that is by Lemma 20, therefore by Theorem 5(i) in Section 2.6. This if is then is , hence , as required. □

5.3. Consequences for the Complete Forcing Notions

We continue to argue under the assumptions and notation of Definitions 7 on page 22 and 8 on page 25. Coming back to the sequence of -systems given by Definition 7, we note that every -system belongs to .

Let be , and let mean: . Note that implies , whereas implies . Lemma 22 takes the following form:

Lemma 24

(in ). Assume that , φ is a closed formula, . Then:

- (i)

- If and , , then , and accordingly,if and , then

- (ii)

- and contradict to each other.

The following result will be very important.

Lemma 25

(in ). If , φ is a closed formula, , then there is a condition , such that either , or .

Proof.

Let . There is an ordinal such that . Consider the set D of all -systems such that there is a -system that extends and satisfies , and there is also a condition , , satisfying . The set D belongs to (with as definability parameters) by Lemma 23. Therefore by Lemma 19 there is an ordinal , such that the -system n-solves D. We have two cases.

Case 1: . Then there exist: a -system extending and satisfying , and a condition , , with . By definition there is an ordinal such that . Now let . Then , hence and .

Case 2: There is no -system that extends . Prove that . Suppose towards the contrary that this fails. Then, by (F8) in Section 5.2, there exists a -system extending , and a condition , such that . Define . Then by definition the -system belongs to , and moreover the -system U witnesses that . But this contradicts the Case 2 assumption. □

5.4. Truth Lemma

According to the next theorem (“the truth lemma”), the truth in the generic extensions considered is connected in the usual way with the relation . We continue to argue under the assumptions and notation of Definitions 7 on page 22 and 8 on page 25.

Theorem 10.

Assume that and φ is a -formula. Then is true in iff there is a condition such that .

Proof.

We proceed by induction. Suppose that is an atomic formula of type (F3) of Section 5.2. (The case of formulas as in (F2) is pretty elementary.) To prove the implication , assume that and , where and . Then by definition ((F3) in Section 5.2) there exists a condition satisfying and . There are conditions such that and , but not necessarily . We only know that for all . Therefore . The set Z belongs to since so do as elements of (whereas about we only assert that ). Therefore a condition can be defined by:

and we still have and . It follows that by genericity, hence . But then , as required.

To prove the converse, assume that . There exists a condition such that , and we have , as required.

Rather simple inductive steps (F4), (F5) of Section 5.2 are left for the reader.

Let us carry out step (F6). Let . Suppose that and . By definition there exists a name such that . The formula is then true in by the inductive hypothesis. But coincides with , where , . We conclude that is true in , as required.

To prove the converse, let , that is, , be true in . As X is relativized to , there is a set in satisfying in . By Lemma 21, there is a name with , so holds in . The inductive hypothesis implies that some satisfies , hence , as required.

Finally, let us carry out step (F8), which is somewhat less trivial. Prove the lemma for a formula , assuming that the result holds for . If is false in then is true. Thus by the inductive hypothesis, there is a condition such that . Then for any is impossible by Lemma 24 above.

Conversely suppose that holds for no . Then by Lemma 25 there exists such that . It follows that is true by the inductive hypothesis, therefore is false. □

6. Invariance

The goal of this section is to prove Theorem 9 on page 24, and thereby accomplish the proof of Theorem 8, and the proof of Theorem 2 (the main theorem) itself. The proof makes use of the relation introduced in Section 5, and exploits certain symmetries in , investigated in Section 6.5.

6.1. Hidden Invariance

Theorem 9 belongs to a wide group of results on the structure of generic models which assert that such-and-such elements of a given generic extension belong to a smaller and/or better shaped extension. One of possible methods to prove such results is to exploit the homogeneity of the forcing notion considered, or in different words, its invariance w.r.t. a sufficiently large system of order-preserving transformations. In particular, for a straightforward proof of Theorem 11 below, which is our key technical step in the proof of Theorem 9, the invariance of the forcing notion under permutations of indices in (to permute areas and ) would be naturally required, whereas is definitely not invariant w.r.t. permutations.

On the other hand, the auxiliary forcing relation is invariant w.r.t. permutations. Theorem 10 in Section 5.4 conveniently binds the relation with the truth in -generic extensions by means of a forcing-style association. This principal association was based on the -completeness property (Definition 7 on page 22 and Theorem 6). Basically it occurs that some transformations, that is, permutations, are hidden in construction of , so that they do not act explicitly, but their influence is preserved and can be recovered via the relation .

This method of hidden invariance, that is, invariance properties (of an auxiliary forcing-type relation like ) hidden in by a suitable generic-style construction of , was introduced in Harrington’s notes [22] in in the context of the almost disjoint forcing (in a somewhat different terminology from what is used here). It was introduced independently by one of the authors in [37] in the context of the Sacks forcing and its Jensen’s modification in [38]; see e.g., [3,28,39] for further research in this direction based on product and iterated versions of the Sacks and Jensen forcing earlier studied in detail in [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

6.2. The Invariance Theorem

We still argue under the assumptions and notation of Definitions 7 on page 22 and 8 on page 25.

Let be the group of all finite permutations of , that is, all bijections since the set is finite. If then the subgroup consists of all satisfying for all . If , and then put .

If in addition then define by , all n.

Similarly if and , then define such that and for all . The following is the invariance theorem.

Theorem 11

(in ). Assume that , , , φ is a closed parameter free formula of , , and . Then iff .

A lengthy proof of Theorem 11 follows below in this Section.

6.3. Proof of Theorem 9 from the Invariance Theorem

Under the assumptions of Theorem 9, consider an arbitrary set , , and assume that (see Definition 8) and it is true in that a is parameter free definable in , i.e., , where is a parameter free -formula. Let and . The goal is to prove that . This is based on the next lemma.

Lemma 26.

The set belongs to .

Proof.

Note that, by Lemma 23, the set:

is definable in by a formula with sets in as parameters, say in , where is a sole parameter. Recall that is -generic over , and . Let be a canonical -name for , and ⊩ be the -forcing relation over . We claim that:

belongs to , of course. The direction is obvious.

To establish , assume that the right-hand side fails. Then there is a condition such that and . We note that the set:

is dense in over . Therefore, by the genericity of , there exists a number such that . Accordingly, there is a permutation satisfying and .

We put ; this is still a -generic element of , with since , and we have . It follows, by the choice of , that fails in , and hence by the choice of . However , thus we have .

It remains to notice that, by Theorem 10,

Therefore . But by Lemma 26. We conclude that , as required.

This completes the proof of Theorem 9 from Theorem 11.

6.4. The Invariance Theorem: Setup

We still argue under the assumptions and notation of Definitions 7 on page 22 and 8 on page 25.

Here we begin the proof of Theorem 11. It will be completed in Section 6.6.

We fix m, , , , , and with , as in Theorem 11. Suppose towards the contrary that , but fails. By definition there is an ordinal such that , but fails. Then we have:

- (A)

- a -system with , and a condition , , such that , but still holds by Lemma 22.

We now recall that any condition is a map , defined on , and each value is a pair of a set and , with strictly, in . We define the support:

then , , and strictly, so that is a bounded subset of . In particular, is a bounded subset of in . Therefore there is:

- (B)

- A bijection , , such that and .

Furthermore, as , the -system is -size, and hence the set satisfies in . It follows that there exists:

- (C)

- A sequence of bijections , such that (see above), , and if then there is an ordinal such that .

6.5. Transformation

In continuation of the proof of Theorem 11, we now define an automorphism acting on several different domains in . It will be based on and of Section 6.4 and its action will be denoted by . Along the way we will formulate properties (D)–(H) of the automorphism, a routine check of which is left to the reader.

We argue under the assumptions and notation of Definitions 7 on page 22 and 8 on page 25.

If and then is defined by for all . In particular, . This defines and for all and .

- (D)

- is a bijection and , and if then by (C).

If then let . If then let .

If U is a -system then define a -system , such that:

If then let be defined so that:

where and by the above. These are consistent definitions because .

- (E)

- for any -system U. The map is a bijection of onto itself and onto itself for any .

- (F)

- for any . The map is a -preserving bijection of onto .

If in addition (not necessarily ), then if conditions satisfy , then easily , where . This allows us to define for every , where is any condition satisfying .

- (G)

- If then is a -preserving bijection of onto .

If and (see Section 5.1) then we define , and accordingly if is a -formula then is obtained by substituting for each name in .

- (H)

- If , , then the mapping is a bijection of onto and a bijection of -formulas onto -formulas.

Remark 6.

The action of is idempotent, so that e.g., for any etc. This is because we require that and for all .

The action of is constructible on , , -systems, , since both π and the sequence of maps belong to by (B), (C).

If then the action of on and names in belongs to , since the extra parameter does not necessarily belong to .

It is not unusual that transformations of a forcing notion considered lead to this or another invariance. The next lemma is exactly of this type.

Lemma 27

(in ). Assume that , , , , , and φ is a closed formula of , . Then iff .

Proof.

We argue by induction on the structure of . Routine cases of atomic formulas (F2) and steps (F4) and (F5) of Section 5.2 by means of (D)–(H) are left to the reader. Thus we concentrate on atomic formulas of type (F3) and steps (F6) and (F8) in Section 5.2. In all cases we take care of only one direction of the equivalence of the lemma, as the other direction is entirely similar via Remark 6 just above.

Formulas of type (F3). Let be , where and . Assume that . Then by definition there is a condition such that and . Then and belong to , , and , so we have , as required.

Step (F6). Let . Suppose that . By definition there exists a name such that , Then we have by the inductive hypothesis. But coincides with , where by (H) above. We conclude that , that is, , as required.

Step (F8). Prove the lemma for a formula , assuming that the result holds for . Note that , hence . Suppose that fails. By definition there is a -system extending , and a condition , , such that . Then by the inductive hypothesis. Yet belongs to , extends , and satisfies by (E), hence belonging even to by the choice of , and in addition and by (F). We conclude, by definition, that fails too, as required. □

6.6. Finalization