Abstract

Let be a graph and be a function. Given a vertex u with , if all neighbors of u have zero weights, then u is called undefended with respect to f. Furthermore, if every vertex u with has a neighbor v with and the function with , , if has no undefended vertex, then f is called a weak Roman dominating function. Also, the function f is a perfect Roman dominating function if every vertex u with is adjacent to exactly one vertex v for which . Let the weight of f be . The weak (resp., perfect) Roman domination number, denoted by (resp., ), is the minimum weight of the weak (resp., perfect) Roman dominating function in G. In this paper, we characterize those trees where the perfect Roman domination number strongly equals the weak Roman domination number, in the sense that each weak Roman dominating function of minimum weight is, at the same time, perfect Roman dominating.

Keywords:

Perfect Roman dominating function; Roman dominating number; weak Roman dominating function MSC:

05C69

1. Introduction

In this paper, we study finite, undirected, simple graphs. Let G be a graph characterized by the vertex set and the edge set . The order of the graph is the number of vertices in the graph and here it is . Denote by the open neighborhood of . The cardinality of the open neighborhood of a vertex is referred to as the degree of that vertex. For a given tree, vertices with degree one are called leaves and those adjacent to leaves are called support vertices. If a support vertex is adjacent to only one leaf, then it is called a weak support vertex. Otherwise, it becomes a strong support vertex. Here, the set of all support vertices of a given tree T is denoted by . All leaves of T is denoted by . Set and . Denote by the set of all leaves that are neighbors of the support vertex x. Set . When a tree T has a root, let be the sub-rooted tree rooted at v for any vertex v. More definitions and notations can be found in e.g., [1].

Inspired by the work entitled “Defend the Roman Empire!” by Ian Stewart [2], recently Cockayne et al. [3] introduced the Roman dominating function in graphs. For a graph function , the vertex set can be partitioned as , where . The functions and the ordered partitions form a one-to-one correspondence. For this reason, it is handy to set . If every vertex u with has at least one neighbor v with , then the function is referred to as a Roman dominating function (RDF). The weight of an RDF f is . We denote by the minimum weight of an RDF of G. It is called the the Roman domination number of G. For some further results on Roman dominating function in graphs, we recommend the reader to consult the papers [4,5,6,7]. RDFs are useful in the study of generalized k-core percolation [8], where -removable, -removable, and non-removable vertices.

Henning, Klostermeyer and MacGillivray [9] introduced the concept of perfect Roman domination in graphs. An RDF is referred to as a perfect Roman dominating function (PRDF) when each vertex u with has only one neighbor v such that [9]. The minimum weight of an RDF is represented by and is called the perfect Roman domination number. In other words,

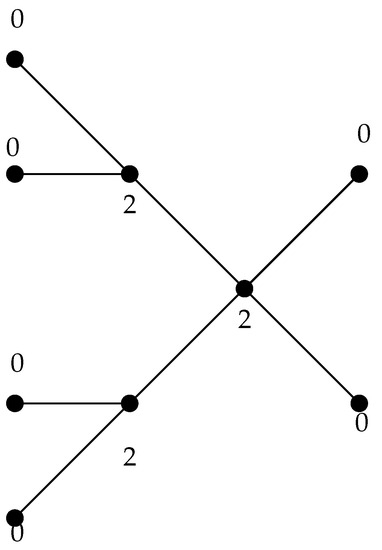

Note that for any graph G, is valid. This is because is a PRDF for G. Note also that every graph G of order n satisfies , as one can define a perfect Roman dominating function f by letting for any vertex u of G. A PRDF of G with minimum weight is also called a -function (see Figure 1). For some recent results on perfect Roman domination number of graphs we refer the readers to the papers [10,11].

Figure 1.

-function of a tree T.

For graph and function , a vertex u with is undefended with respect to f if all its neighbors have only zero weight. Henning and Hedetinemi [12] defined the weak Roman dominating function as follows. The function f is a weak Roman dominating function (WRDF) if each vertex u with is adjacent to a vertex v with such that the function defined by , and if , has no undefended vertex. Let the weight of f be . The weak Roman domination number, denoted by , is the minimum weight of a WRDF in G, that is:

It was shown by Henning and Hedetinemi [12] that the problem of computing is NP-hard. This is true even when the graph in consideration is bipartite or chordal. Hence, finding the weak Roman domination number for some special classes of graphs as well as finding some good bounds for this invariant is of great importance. For some recent results on the weak Roman domination number of graphs we refer the interested reader to the papers [4,13].

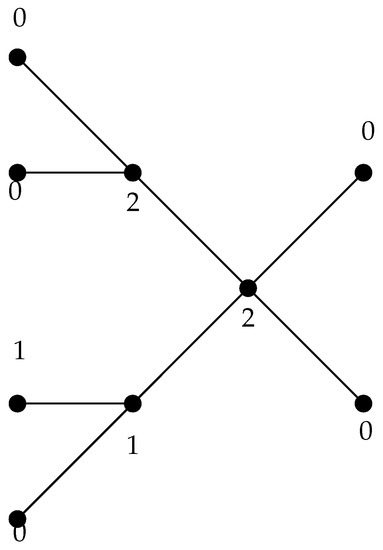

Note that for every graph G. Clearly, if G is a graph with , then every -function is a -function. However, not every -function is an -function (see Figure 2), even when . For example, consider the path . We say that and are strongly equal, denoted by , if every -function is an -function. In this paper, we provide a constructive characterization of trees T such that . Other interesting examples of characterizations for strong equalities have been discussed in [4,6,7,14,15].

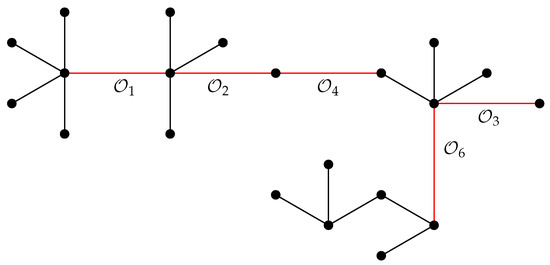

Figure 2.

-function over a tree T, which is not a perfect Roman dominating function (PRDF).

2. Constructive Characterization of Strong Equality

We start with the following essential lemmas.

Lemma 1.

Let T be a tree with . Then T has no weak support vertex with degree two.

Proof.

Let T be a tree with and u be a weak support vertex of it with leaf neighbor v. Let f be a -function and . If , then, clearly and so the function g with , and for , is a -function, which is not a PRDF. This leads to a contradiction. Thus, we may assume that . We first assume that . Then, it is true that , or , . Hence, f is not a PRDF, which leads to a contradiction. Now, assume that . Then, . If , then , or , . Accordingly, f is not a PRDF, which is a contradiction. Thus, . Therefore, function by and and for , is a -function, which is not a PRDF. This leads to a contradiction. Hence, T has no weak support vertex with degree two. □

Lemma 2.

Fix a tree T. Assume that and u is a strong support vertex with . If f is a -function, then . Also, if then any non-leaf neighbor of it has weight 0.

Proof.

Let . We first assume that . Since f is a PRDF, we deduce that . Then by re-assigning to the vertex u the value 2 and to the vertices the value 0, we get a new WRDF with weight less than , which is a contradiction. Next, assume that , then . If for any vertex we have , then by re-assigning to the vertex u the value 1 and to the vertex x the value 0, we get a new -function that is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Hence, we can assume that and . Since f is a -function, there exists a vertex such that and . Thus, by re-assigning to the vertex u the value 2 and to the vertices the value 0, we obtain a new -function that is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Hence . Assume that and . If , then by re-assigning to the vertices u and x the value 1, the -function is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Therefore, . □

In the case of , a family of trees can be defined as follows:

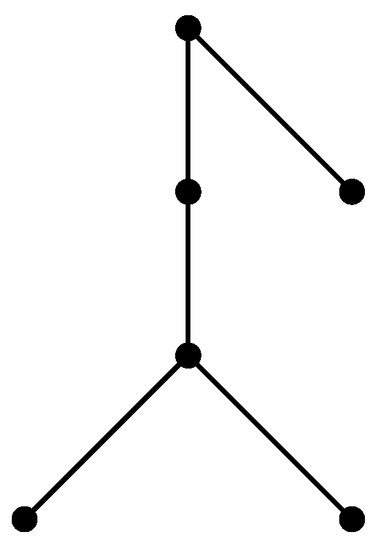

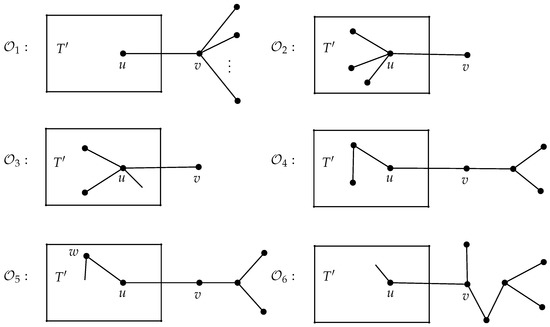

Let F be the tree depicted in Figure 3 and be the collection of trees T that can be obtained from a sequence of trees, where is a star with , and can be obtained recursively from by one of the following six operations defined below and illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

The tree F.

Figure 4.

The operations .

- Operation Add a star , and link its central vertex v to a vertex u of such that .

- Operation Add a new vertex v to and link it to a strong support vertex u of with at least three leaf neighbors.

- Operation Add a new vertex v to and link it to a strong support vertex u of with .

- Operation Add a star , and link a leaf v to a leaf u of that is adjacent to a strong support vertex of .

- Operation Add a star and join a leaf to vertex u of such that every -function of assigns to the vertex u the value 0.

- Operation Add a tree F (as depicted in Figure 3) and join its support vertex v with degree two to a vertex u of such that and every -function of assigns to the vertex u the value 2.

Next, we will show that for every tree in the family (see Figure 5 for an example of a tree in this family), we have .

Figure 5.

An example of a tree T in the family , obtained from tree by Operations and .

Lemma 3.

Suppose that T is a tree in the family , then .

Proof.

We proceed by induction on the order of a tree . If , then and clearly . Suppose that and that for every tree in of order , where , we have . Assume that has order n. Thus, T can be obtained from a sequence of trees , where and where and . For each , the tree can be constructed by via one of the operations .

Set . We know that has less than n vertices. Applying the inductive hypothesis to , we know that . Suppose that f is a -function of T, where the sum of the values assigned to all leaves under f is the minimum. We restrict the function f to the tree and denote it by . For any vertex , the equality holds. Six different situations are considered in the sequel.

Case 1.T is derived by through Operation .

Assume T is obtained from by adding a star , with central vertex v and leaves , and adding the edge such that . Then u can not get the value 0 under any -function. Hence every PRDF on can be extended to a PRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to v and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of v. Hence, by the statement above, and inductive hypothesis, we obtain

Conversely, the vertex v is a strong support vertex of T and so we can see that and . If , then is a WRDF on and so

Now assume that , then is a WRDF on tree and so

Therefore, we must have equalities throughout the inequality chain (1). In particular, .

Now, assume that . Then there is a -function g such that g is not a PRDF. Since v is a strong support vertex, hence . If , then the function is a -function that is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Hence, . Thus, the function is a WRDF on tree and so . This is a contradiction. Therefore, .

Case 2.T is derived by through Operation .

Assume that is a -function. We have and therefore is extended to a PRDF on T by giving the weight 0 to v. Hence, by inductive hypothesis, we obtain

Conversely, the vertex u is a strong support vertex of T and so we can see that and . Hence, is a WRDF on and so . Therefore, we must have equalities throughout the inequality chain (4). In particular, . Assume that . Thus, there is a -function g such that g is not a PRDF. Since u is a strong support vertex, then and . Hence, the function is a -function that is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Therefore, .

Case 3.T is derived by through Operation .

Assume that is a -function and . Hence, we assume that and . Then can be extended to a PRDF on T by assigning the weight 0 to v. Hence, by the inductive hypothesis, we obtain

Conversely, the vertex u is a strong support vertex of T and so we obtain that and . Hence, is a WRDF on and so Therefore, we must have equalities throughout the inequality chain (5). In particular, . Assume that . Thus, there is a -function g such that g is not a PRDF. Since u is a strong support vertex, then and . Hence, the function is a -function that is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Therefore, .

Case 4.T is derived by through Operation .

Assume T is obtained from by adding a star , with central vertex x and leaves , and adding the edge where u is a leaf that is adjacent to a strong support vertex w of . Assume that is a -function. Note that w is a strong support vertex, we assume that and . By the inductive hypothesis, is a -function. Then, we extend to a PRDF on T by giving the weight 2 to x and the weight 0 to the vertices and z. Hence, by the statement above, and the inductive hypothesis, we obtain

Conversely, the vertex x is a strong support vertex of T. Also, and hold. Hence, is a WRDF on and therefore

Therefore, we must have equalities throughout the inequality chain (6). In particular, .

Assume that . Then there is a -function g such that g is not a PRDF. Since x is a strong support vertex, we may assume that and . Then the function is a -function on tree that is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Therefore, .

Case 5.T is derived by through Operation .

If T is constructed from via adding a star with central vertex x and leaves , and joining leaf v of the star to vertex u of such that every -function of gives to the vertex u the value 0. Assume that is a -function. By the hypothesis, . On the other hand, is a -function since . Thus, can be extended to a PRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to x and the weight 0 to and z. Hence, by the statement above, and inductive hypothesis, we obtain

Conversely, the vertex x is a strong support vertex of T and so we can see that and . Hence, is a WRDF on and therefore

Accordingly, we know these equalities across the inequality chain (8). Accordingly, .

Assume that . Then there is a -function g such that g is not a PRDF. Since x is a strong support vertex, we may assume that and . Then, the function is a -function on tree and so . Since g is not a PRDF, we deduce that is not a PRDF, which leads to a contradiction. Therefore, .

Case 6.T is derived by through Operation .

Suppose that T is derived from via adding a tree F and joining its support vertex v with degree two to a vertex u of such that and every -function of assigns to the vertex u the value 2. Let , , and .

Suppose that is a -function. Then . Hence, we extend to a PRDF on T by assigning the weight 0 to , the weight 1 to w and the weight 2 to r. Hence, by the statement above, and the inductive hypothesis, we obtain

Conversely, the vertex r is a strong support vertex of T and so we can assume that and . Without loss of generality, we may assume that or . If , then and also is a WRDF on and therefore

Next, suppose that , then and we may assume that . Then the function such that and for , we have , is a WRDF on and so

Accordingly, we must have equalities throughout the inequality chain (10). In particular, .

Now, suppose that . Then there is a -function g such that g is not a PRDF. Since r is a strong support vertex, we may assume that and . If , then we can assume that . Then is -function that is not a PRDF, which leads to a contradiction. Hence, we assume that . We may assume that and . If , then is -function with weight . This is a contradiction. Hence, we assume that . Thus, function by and for is a -function such that , which is a contradiction. Therefore, . This completes the proof. □

Next we have our main results as follows.

Theorem 1.

Let T be a tree. We have if and only if T is or .

Proof.

Suppose T is a tree of order n. Moreover, we have . When , holds. Without loss of generality, we suppose T is a tree or order . The induction method will be used in terms of n in the following. We can safely assume that because a path has a -function which is not a PRDF. In the case of , . Furthermore, . What remains to be shown is the case of . Assume that every tree of order having lies in . Suppose that T has n vertices and . Let f be a -function. It is also safe to view T as a tree with a diameter of at least three because any star having at least four vertices is a member of . In the case of , T becomes a double star . We can safely suppose that . If , then and clearly , which is a contradiction. Hence, we assume that . If , then T has a -function that is not a PRDF, which is a contradiction. Hence, we assume that . Then because it is obtained from a star by using Operation . Therefore, we assume that and T has a strong support vertex u with .

Let , and f be a -function. Then and is a PRDF for tree and so . Now, assume that is a -function, then can be extended to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 0 to the vertex v, and then . Accordingly, . On the other hand, and so . Therefore, . If and are not strongly equal, every -function that is not a PRDF can be extended to a -function by giving 0 to v, that is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction with . Therefore, and by induction on , we have . We conclude that as it is obtained from by using Operation . Hence, we assume that the following fact holds.

Fact 1. If u is a strong support vertex of a tree T, then .

We root T at a leaf of a diametral path from to a leaf farthest from . Then Lemma 1 and Fact 1, implies that . Among all -functions, let f be chosen so that the weight assigned to is as large as possible. Since , it then follows that f is a -function. We consider the following two cases:

Case 1..

Let . Clearly and is a PRDF on . Hence, . Assume that g is a -function. Then we can extend g to a WRDF for T by assigning 0 to , and so . Consequently, . Hence and so . Therefore, . If and are not strongly equal, then every -function which is not a PRDF can be extended to a -function, by assigning 0 to , that is not a PRDF. This leads to a contradiction with . Therefore and by induction on , must be true. Therefore, must hold as it is derived from by applying Operation .

Case 2..

Then Lemma 2 implies that . If , then re-assigning to the vertices and the weight 1 produces a new -function which is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Hence, . If is a child strong support vertex of , then we can assume that and so f is not a PRDF, which is a contradiction. On the other hand, Lemma 1 implies that has not a weak support vertex as child. Thus every child of is a leaf. Since holds, is not a strong support vertex. Assume that is a weak support vertex. Let and . Without loss of generality, we may assume that . Then re-assigning to the vertices and z the weight 1 and to the vertex the weight 0, we obtain a new -function which is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Hence, we assume that . Thus, Lemma 2 implies that and . Since f is also a -function, then . Assume that . Since f is a -function, every vertex with weight 0 is adjacent to a vertex with weight 2, and then by giving to the vertex the weight 0 and to the vertex the weight 1, we obtain a new -function, contradicting Lemma 2. Hence, and so . Two subcases follow as follows:

Subcase 2.1.

First, we assume that is a support vertex. Since , it is not a strong support vertex so is a weak support vertex. Let . Without loss of generality, we can assume that since . If has a child u that is a strong support vertex, then we can assume that , contradicting that f is a -function of T. Thus, does not have a strong support vertex as a child. On the other hand, Lemma 1 implies that does not have a weak support vertex as a child. Hence, every child of , except , plays a role similar as . Assume that and u is a child of other than and . Let . Since f is a -function and , hence is a PRDF on , and so . Assume that is a -function. Let and . Then, we can assume that and . If , then we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it. Hence, . Next, assume that . Since , for every such that , there exists at least one vertex such that . Hence, we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it. Hence, . Consequently, in both cases, . Therefore, and so . If and are not strongly equal, then every -function which is not a PRDF is extended to a -function by giving the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it, that is not a PRDF. This leads to a contradiction with . Therefore, and by induction on , we have . We conclude that , as it is obtained from by using Operation .

Thus, we can assume that . If , then clearly and so by re-assigning to the vertices and the value 1 and to the vertex the value 0 we get a new -function which is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Hence, we can assume that . Let . Since f is a -function and , then is a PRDF on and so . Assume that is a -function. If , then we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to , the weight 1 to and the weight 0 to the remaining vertices of T, which is a WRDF of T of weight , and so . Next, assume that . If for every vertex with , there exists at least one vertex with , then we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to , the weight 1 to and the weight 0 to the remaining vertices of T, which is a WRDF of T of weight , and so . We assume that there exists a vertex with such that for every , we have . Then for every vertex , we get , since is a -function. Hence, there exists a vertex such that , since . Then by re-assigning to the vertices and y the value 1, we get a new -function . Consequently, . Hence, and so .

Now assume that is a -function. We first assume that . Then we can extend to a -function by assigning the weight 2 to , the weight 1 to and the weight 0 to the remaining vertices of T. This is a contradiction since every -function assigns to the vertex the value 2. Next, assume that . If for every vertex with , there exists at least one vertex with , then we can extend to a -function by assigning the weight 2 to , the weight 1 to and the weight 0 to the remaining vertices of T. This is a contradiction since every -function assigns to the vertex the value 2. Hence, we can assume that every -function assigns to the vertex the value 2.

Also, if and are not strongly equal, then every -function which is not a PRDF, can be extended to a -function by assigning the weight 2 to , the weight 1 to and the weight 0 to the remaining vertices of T, that is not a PRDF on tree T, which leads to a contradiction with . Therefore, and so by induction on , we have . We conclude that since it is obtained from by using Operation .

Now, assume that is not a strong support vertex. Then, we observe that every child of plays a similar role as . Let . Since f is a -function and , then is a PRDF on and so . Assume that is a -function. Let and . Then, clearly we can assume that and . If , then we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it. Hence . Next, assume that . Since , for every such that , there exists at least one vertex such that . Hence, we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it. Hence, . Consequently, in both cases, . Therefore, and so . Assume that is an arbitrary -function. Then we can assume that . Hence, as before, it can be extended to a -function g by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it. Since , we deduce that g is a -function and so is -function. Therefore, and via induction on , holds. Therefore, as it is derived via by applying Operation .

Subcase 2.2.

If , then by re-assigning to the vertex the value 0, to the vertex the value 1 and to the vertex the value , we arrive at a new WRDF g with weight at most such that . This is a contradiction. Thus, we may assume that .

First, we assume that is a support vertex. Let . Since , hence is a PRDF for and so . Now, assume that be a -function. Since in tree is a strong support vertex, we can assume that . Then, we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it. Hence, . Consequently, in both cases, . Therefore, and so . Assume that is an arbitrary -function. Then, we can assume that and . Hence, as before, it can be extended to a -function g by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the three neighbors of it. Since , we deduce that g is a -function and so is -function. Therefore, and via induction on , holds true. Similarly, it is easy to see that holds. This can be seen as it is derived by applying Operation .

Next, suppose is not a support vertex. By Lemma 1, the vertex does not have a weak support vertex as a child. Also, by Lemma 2, the vertex does not have a strong support vertex as a child with degree three. We assume that has as a child, a strong support vertex v with . Let . Then, clearly and is a PRDF for . So . Assume that is a -function. can be extended to a WRDF on T by giving the weight 2 to v and the weight 0 to the all leaves neighbors of it. Hence, . Consequently, in both cases, . Hence, and so . Now, assume that is an arbitrary -function. It can then be extended to a -function g by assigning the weight 2 to v and the weight 0 to the all leaves neighbors of it. Since , we deduce that g is a -function and so is a -function. Therefore, . Using induction on , holds true. Similarly, . This is because and the Operation .

Next, we suppose that for any child support vertex v of , we have . Let . Assume that is a leaf vertex of a tree , other than and y, and at maximum distance from . Let be the shortest path from to . Clearly, . As noted earlier, . We proceed depending on t.

We first suppose that . Then Lemma 1 implies that and so is a strong support vertex. Without loss of generality, we may assume that and so , since f is a -function and . Hence, . If is not a support vertex, then by Lemma 1 any child u of is a strong support vertex and so we can assume that . Then by re-assigning to the vertex the value 0, we get a new WRDF with weight less than . This is a contradiction. Assume that is a weak support vertex. Let . Without loss of generality, we may assume that and . Then by re-assigning to the vertex the value 0 and to the vertex the value 1, we produce a new -function which is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Thus, we may assume that is a strong support vertex. If and , then we can assume that and . Then by re-assigning to the vertex the value 0 and to the vertices and the value 1, we get a new -function which is not a PRDF. This is a contradiction. Hence, we may assume that and so . Then, Lemma 2 implies that . Let . Then, clearly and is a PRDF for and so . Assume that is a -function. Then, we can extend to a WRDF on T by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to the all leaves neighbors of it. Hence, . Consequently, in both cases, . Therefore, and so . Now, assume that is an arbitrary -function. Then it can be extended to a -function g by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to all leaves neighbors of it. Since , we deduce that g is a -function and so is a -function. Therefore, . Using induction on , must be true. Therefore, we have . This is due to and the Operation .

Suppose that . Since plays the same role as , we may assume that and is a strong support vertex of degree three. Let and . Then is a PRDF for and so . Now, assume that is a -function. If , can be generalized to a WRDF on T by giving the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to all neighbors of it. Hence, . Assume that . Then, we can assume that , and . If , then we can extend to a -function g by re-assigning to the vertex the value 2 and to the value 0 and by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to all neighbors of it, and so . Assume that . Then we can assume that . We can extend to a -function g by re-assigning to the vertex the value 2 and to the vertices and the value 0 and by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to all neighbors of it, and so . Consequently, in all cases, . Hence, and so . Now, assume that be an arbitrary -function. Then, as before, it can be extended to a -function g by re-assigning to the vertex the value 2 and to the vertices and the value 0 and by assigning the weight 2 to and the weight 0 to all neighbors of it. Since , we deduce that g is a -function and so is a -function. Therefore, . Via induction on , holds true. Consequently, it can be seen that . This is again due to as well as the Operation . The proof is then completed as desired. □

3. Conclusions

Ian Stewart’s work “Defend the Roman Empire!” [2] initially introduced the notion of Roman dominating functions. In recent years, many variations of Roman domination have been proposed due to different conditions on Roman domination, e.g., weak Roman domination [12] and perfect Roman domination [9]. Among the problems of Roman domination, the strong equality results have attracted great attention. In this paper, we studied the class of trees in which the perfect Roman domination number is strongly equal to the weak Roman domination number. This strongly equality means that each weak Roman dominating function of minimum weight is equivalent to a function that is deemed as perfect Roman dominating. We formulated some interesting conditions which we hope can be useful in stimulating relevant research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., M.D. and H.R.; formal analysis, A.A., M.B., H.R. and Y.S.; writing–original draft preparation, A.A., M.D. and H.R.; writing–review and editing, A.A., M.D., H.R. and Y.S.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. and Y.S.

Funding

The research of A.A. was in part supported by a grant from Shahrood University of Technology. The work was supported in part by the UoA Flexible Fund No. 201920A1001 from Northumbria University.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the academic editor and the three anonymous referees for detailed constructive comments that helped improve the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haynes, T.W.; Hedetniemi, S.T.; Slater, P.J. Fundamentals of Domination in Graphs; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, I. Defend the Roman Empire! Sci. Am. 1999, 281, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockayne, E.J.; Dreyer, P.A.; Hedetniemi, S.M.; Hedetniemi, S.T. Roman domination in graphs. Discret. Math. 2004, 278, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, J.D.; Dantas, S.; Rautenbach, D. Strong equality of Roman and weak Roman domination in trees. Discret. Appl. Math. 2016, 208, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudo, S.; Fernau, H.; Sigarreta, J.M. The differential and the Roman domination number of a graph. Appl. Anal. Discret. Math. 2014, 8, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellali, M.; Rad, N.J. Strong equality between the Roman domination and independent Roman domination numbers in trees. Discuss. Math. Graph Theory 2013, 33, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, N.J.; Liu, C.H. Trees with strong equality between the Roman domination number and the unique response Roman domination number. Australas. J. Comb. 2012, 54, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y. Attack robustness and stability of generalized k-cores. New J. Phys. 2019, 21, 093013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, M.A.; Klostermeyer, W.F.; MacGillivray, G. Perfect Roman domination in trees. Discret. Appl. Math. 2018, 236, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkooti, M.; Alhevaz, A.; Rahimi, S.; Rahbani, H. On perfect Roman domination number in trees: Complexity and bounds. J. Comb. Optim. 2019, 38, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkooti, M.; Alhevaz, A.; Rahimi, S.; Rahbani, H. Characterization of perfect Roman domination edge critical trees. Le Matematiche 2019, 74, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, M.A.; Hedetniemi, S.T. Defending the Roman empire–new strategy. Discrete Math. 2003, 266, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valveny, M.; Pérez-Rosés, H.; Rodriguez-Velázquez, J.A. On the weak Roman domination number of lexicographic product graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 2019, 263, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattingh, J.H.; Henning, M.A. Characterizations of trees with equal domination parameters. J. Graph Theory 2000, 34, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, T.W.; Henning, M.A.; Slater, P.J. Strong equality of domination parameters in trees. Discret. Math. 2003, 260, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).