1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of digital communication systems and the exponential increase in multimedia data transmission, ensuring information security has become a critical challenge in modern communication infrastructures. Conventional cryptographic algorithms, although mathematically rigorous and widely adopted, often suffer from limitations when applied to real-time, high-throughput, or resource-constrained environments, particularly in multimedia and embedded systems [

1,

2,

3]. These limitations have motivated extensive research into alternative encryption paradigms that can provide enhanced security while maintaining computational efficiency.

Chaos theory has emerged as a promising foundation for cryptographic system design due to its intrinsic properties, including sensitivity to initial conditions, ergodicity, pseudo-randomness, and deterministic yet unpredictable behavior [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These characteristics align naturally with the core cryptographic principles of confusion and diffusion introduced by Shannon [

8]. Consequently, chaos-based encryption schemes have been widely investigated for applications such as image and video encryption, secure communications, and random number generation [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Various chaotic maps and continuous-time systems—such as the Logistic map, Henon map, Chua circuit, Lorenz chaotic system, and Rossler system—have been employed to construct cryptographic primitives including stream ciphers, permutation–diffusion architectures, and chaotic key generators [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Despite their theoretical appeal, many chaos-based encryption schemes have been shown to exhibit structural weaknesses when implemented in practical environments. In particular, static parameter selection, finite precision effects, and predictable carrier signal characteristics can significantly reduce the effective key space and render systems vulnerable to cryptanalysis, parameter estimation attacks, and chosen-plaintext attacks [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated that chaotic systems with fixed control parameters may lose their chaotic behavior under numerical implementation, especially when discretized using low-order integration schemes [

23,

24]. These observations highlight the necessity for adaptive and intelligent mechanisms that can dynamically regulate chaotic behavior while preserving synchronization between transmitter and receiver.

Fuzzy logic systems provide a powerful framework for handling uncertainty, nonlinearity, and time-varying dynamics in complex systems [

25,

26,

27]. Unlike conventional rule-based controllers with rigid decision boundaries, fuzzy inference systems enable smooth transitions between operating states and allow system parameters to be adjusted in real time based on linguistic rules and contextual information [

28]. In recent years, the integration of fuzzy logic with chaotic systems has gained attention as a means to enhance adaptability, robustness, and security in encryption frameworks [

29,

30,

31,

32]. By embedding fuzzy decision-making into chaotic modulation processes, it becomes possible to dynamically alter encryption parameters, thereby significantly increasing unpredictability and resistance to cryptanalytic attacks.

Among various fuzzy inference structures, the Sugeno-type fuzzy inference system offers notable advantages in terms of computational efficiency and suitability for real-time applications [

33]. Its rule consequents are expressed as linear or constant functions, making it particularly attractive for digital signal processing and embedded implementations. When combined with continuous-time chaotic systems, such as the Lorenz attractor, Sugeno-based fuzzy control can be leveraged to construct adaptive chaotic carriers whose amplitude, state evolution, and modulation characteristics vary continuously in response to the information signal [

34,

35,

36]. This dynamic behavior directly addresses the shortcomings of static chaos-based encryption schemes.

Another critical aspect of cryptographic system evaluation lies in rigorous security analysis. While traditional time-domain and frequency-domain analyses, such as oscilloscope observation and Fourier transform inspection, provide valuable insights into signal concealment, they are insufficient to fully characterize cryptographic robustness [

37]. As a result, quantitative security metrics—including Histogram analysis, NPCR (Number of Pixels Change Rate), and UACI (Unified Average Changing Intensity)—have become standard tools for evaluating sensitivity to plaintext changes and resistance to differential attacks, particularly in multimedia encryption contexts [

38,

39]. Additionally, key sensitivity analysis plays a pivotal role in assessing a system’s resilience against brute-force and key-related attacks, ensuring that minimal key perturbations lead to complete decryption failure.

Against this backdrop, the present study introduces a novel fuzzy–chaotic encryption framework that addresses the identified limitations of existing approaches through adaptive intelligence and multi-layered security design. The proposed system exploits a dynamic mixture of Lorenz chaotic system state variables, numerically integrated using the Euler– Forward method to maintain stability and accuracy in continuous-time modeling. Unlike conventional chaos-based schemes with static carriers, the encryption parameters in the proposed framework are continuously regulated by a Fuzzy Rule-Based Sugeno Inference (FRBSI) mechanism driven by instantaneous information signal thresholds. This adaptive structure substantially enhances unpredictability, enlarges the effective key space, and strengthens resistance against both analytical and brute-force attacks.

The integration of fuzzy inference rules allows real-time adjustment of encryption parameters, offering robust protection against both analytical and brute-force attacks. The framework is developed and thoroughly validated in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, with synchronized transmitter and receiver structures examined in detail. In addition to traditional oscilloscope visualization and Fourier analysis, the cryptographic strength of the system is quantitatively assessed using Histogram analysis, NPCR (Number of Pixel Change Rate), and UACI (Unified Average Changing Intensity) metrics. The key sensitivity of the Sugeno rule base is further demonstrated, showing that even a single-bit difference at the receiver prevents successful decryption. This hybrid intelligent-chaotic architecture provides a novel, effective, and structurally secure framework for next-generation adaptive communication systems.

2. Simulation of Lorenz Chaotic System

In this study, the Lorenz chaotic system was used as the carrier signal for the encryption process. The Lorenz chaotic system was selected because it was the first chaotic system to be synthesized and features more than one state variable [

40]. Since the proposed encryption method requires a chaotic system with at least two state variables, a system with three state variables provides stronger mixing.

To enable execution on a digital platform using an embedded system, the continuous-time Lorenz chaotic system differential equations must be converted into a form suitable for software implementation. This process involves first transforming the equations from the time domain to their frequency-domain representation, followed by discretization and numerical integration. The resulting discrete-time equations are then implemented in software. A detailed description of this procedure is provided in the following sections.

2.1. Continuous-Time Lorenz Equations

The mathematical expressions for the state space of the Lorenz chaotic system are given below, as shown in Equation (1). The x, y, and z parameters in the equation are state variables, and a, b, and c are the constant parameters of the equation.

For the Lorenz chaotic system to be coded in a software environment, it must be converted into a block diagram in the frequency space. For this reason, firstly, the t-space Lorenz equations are transformed into S-space Lorenz equations using the Laplace transform method [

41] Equation (2).

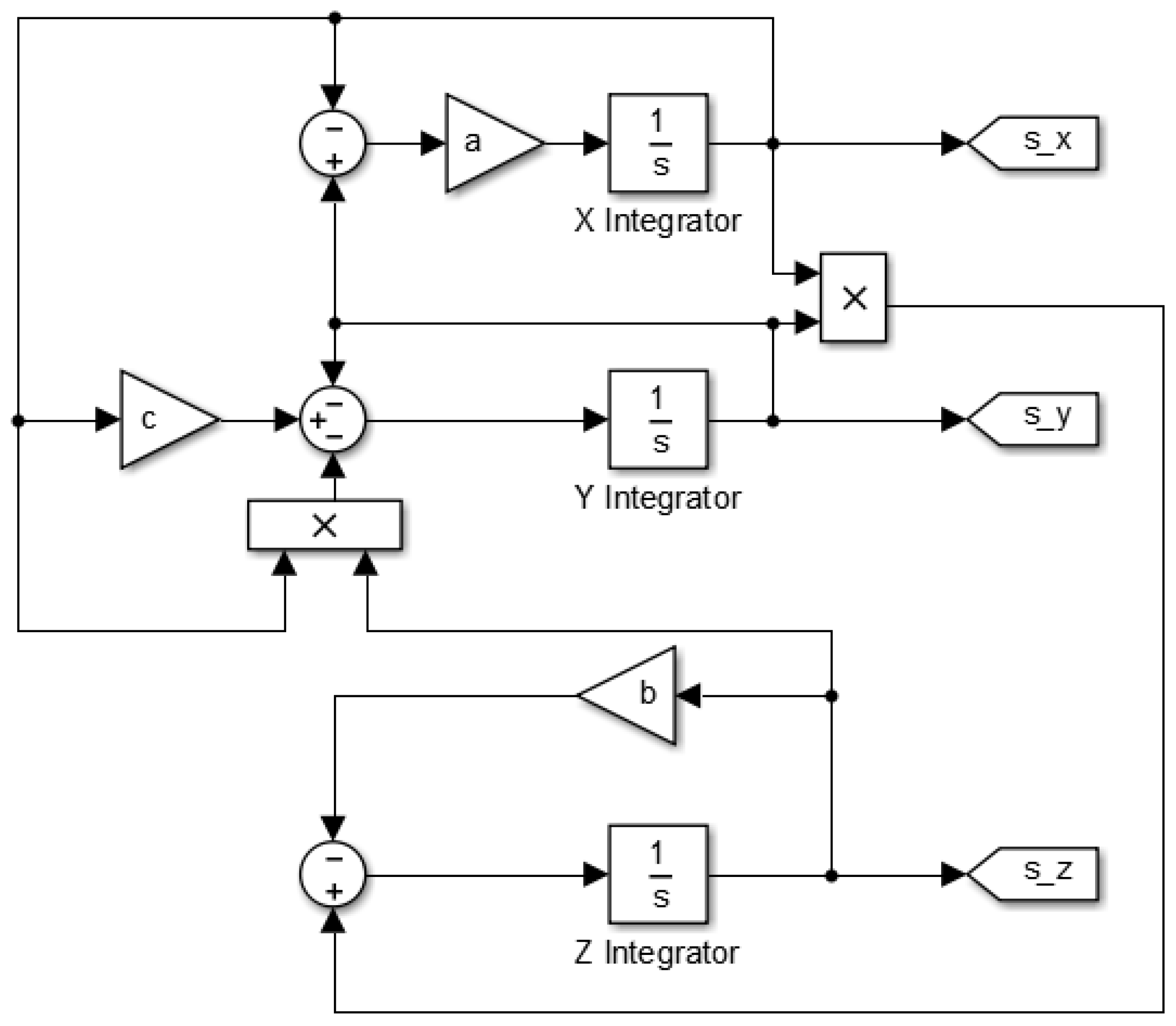

After the S-space transformation, the Lorenz equations are converted into a block diagram form and simulated in the MATLAB-Simulink environment, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

The instantaneous values of the x, y, and z variables obtained during the simulation process were visualized in the x-y, x-z and y-z planes, where a = 10, b = 8/3, and c = 28, with initial values of x = 1, y = −0.5, and z = 1,

Figure 2.

2.2. Coding Lorenz Equations

To implement the Lorenz chaotic system on a digital platform, it is necessary to discretize the mathematical equations of the algorithm. For this purpose, discretization is performed using forward difference equations [

42]. The Euler-Forward method is preferred for the transformation from continuous-time S-space to discrete-time Z-space Equation (3).

The Lorenz discrete-time block diagram obtained after the transformation is visualized in

Figure 3.

The Tsample parameter is calculated by taking into account the rate of change in the x, y, and z variables during the execution of the continuous-time Lorenz chaotic system. In this study, the Tsample value is calculated by applying the time value between two peak values of the Lorenz output signal with “the shortest time interval”/10 rule [

42]. Given the continuous system

, the discrete-time approximation is defined with a fixed step size of h = 0.001 as follows:

To ensure that this discretization does not suppress the chaotic dynamics, the system’s stability was evaluated via the Largest Lyapunov Exponent (LLE), defined as

For the selected step size h = 0.001, the calculation yields a positive value (), confirming that the sensitive dependence on initial conditions and the strange attractor’s topological structure are strictly preserved in the discrete domain. This mathematical verification ensures that the sequences generated by the discrete oscillator maintain the complexity required for secure encryption.

The discretized Lorenz block diagram presented below can be efficiently translated into software code using programming techniques, making the algorithm applicable on digital platforms,

Appendix A.

Considering the continuous-time Lorenz signals, the Tsample parameter was calculated as 1 ms. The time-based changes in x, y, and z states, obtained by running the discrete-time block diagram shown in

Figure 3 under the Tsample = 1 ms sampling condition, are presented in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, and

Figure 6, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the intensity of the discrete-time Lorenz oscillator’s x, y, and z output signals could be adjusted. The Tsample values of the Z

−1 blocks modify this intensity. Thus, the carrier signal intensity value may also be used as a secret parameter in the encryption process. In this study, the Tsample parameters, which are Z

−1 blocks’ period parameters, are set to 1*T

sample.

3. Chaotic-Based Encryption Theory

In this section, both the conventional and the proposed chaos-based encryption mechanisms are examined individually. The first part introduces the conventional approach of encryption, in which the carrier signal is combined with the message signal to produce an encrypted waveform. The second part then explores the proposed FRBSI-based encryption scheme in detail. For both approaches, the transformed representations of the resulting carrier signals are presented, and their characteristics are critically evaluated.

3.1. The Conventional Chaos-Based Encryption

In conventional chaos-based encryption, a chaotic oscillator state variable serves as the carrier signal. The plaintext or time variant information is then imposed on this carrier via AM. In essence, the message signal modulates the amplitude of the chaotic carrier. Embedding the information within the modulated chaotic waveform ensures that the data is conveyed exclusively through the chaotic output, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

If the data to be hidden represents a fixed and unchanging value, it is converted into a variable form by applying certain operations (6). More explicitly, let xc(t) represent the selected state variable of the chaotic oscillator used as the carrier. The transmitted signal s(t) is then given by

where m(t) is the normalized message signal, with appropriate amplitude scaling, and k is a modulation gain constant. During decryption, a synchronized chaotic receiver retrieves

and demodulation yields the original message m(t).

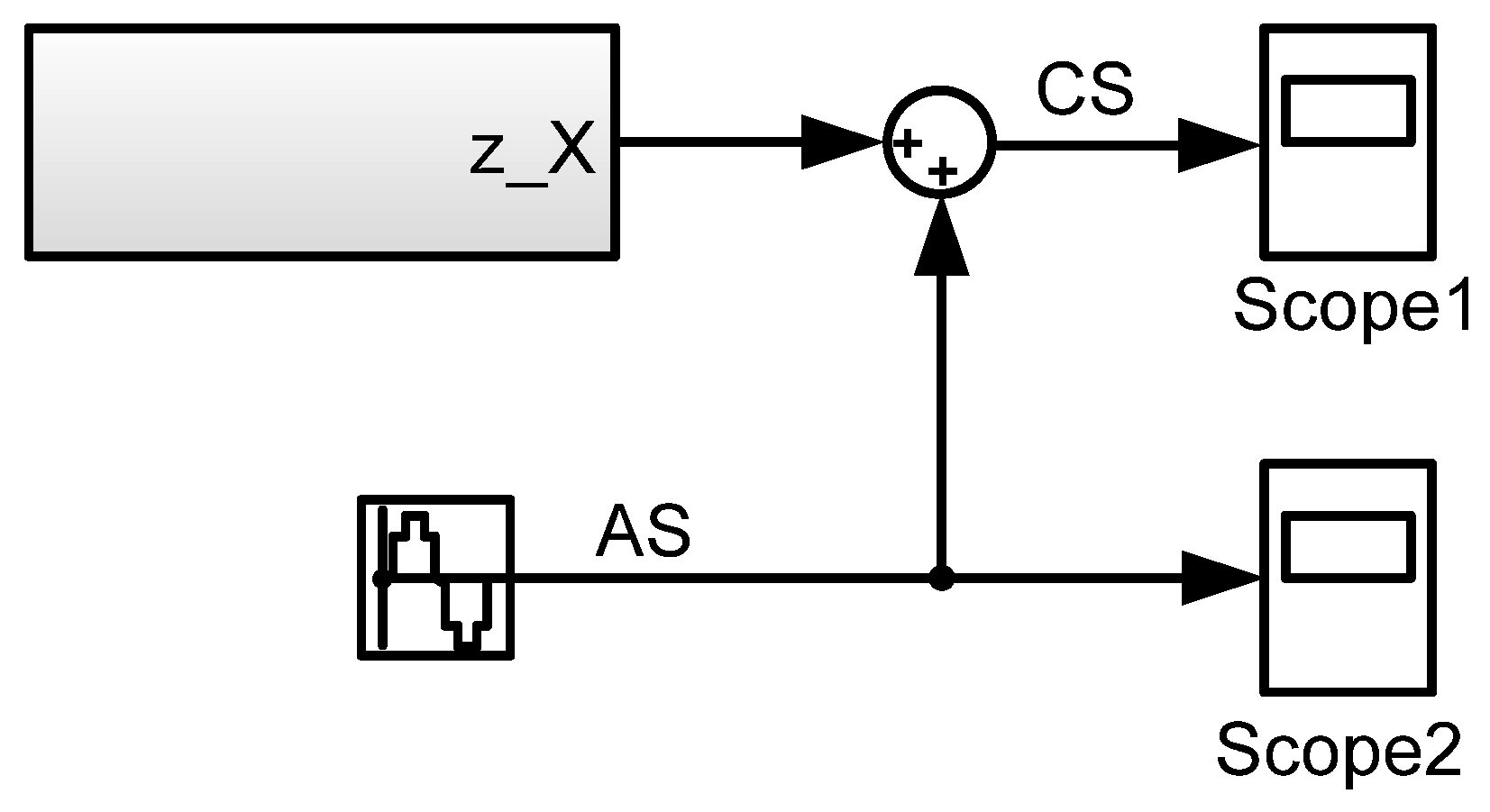

In the simulation application in MATLAB-Simulink based on the conventional encryption method, the X state of the Lorenz oscillator was selected as the variable carrier signal. The amplitude modulation of the carrier signal was performed using a discrete-time sinusoid signal with a frequency of 100 Hz and a peak voltage of 1 V. This structure is shown in

Figure 8.

Figure 9 illustrates the one-dimensional CS-X, CS–Y, and CS–Z plots obtained from a 2.5 s simulation, where CS denotes the crypto signal of Lorenz.X + sinusoidal signal. The results demonstrate that the modulation signal influences the state variables of the chaotic oscillator, shaping them in accordance with its frequency and waveform.

3.2. Proposed FRBSI-Based Chaotic Encryption

The proposed FRBSI-based encryption scheme is presented in

Figure 10. In this method, all variables of the Lorenz signal are systematically incorporated into the modulation process based on predefined fuzzy logic rules.

The encryption structure illustrated in

Figure 10 utilizes a fuzzy logic system comprising four input variables and a single output variable. Three of the inputs correspond to the state signals of the Lorenz oscillator, while the fourth input represents the signal to be encrypted. In this context, the variation function of the message signal directly affects the dynamic properties of the carrier signal, ensuring that the carrier signal remains in a state of constant change.

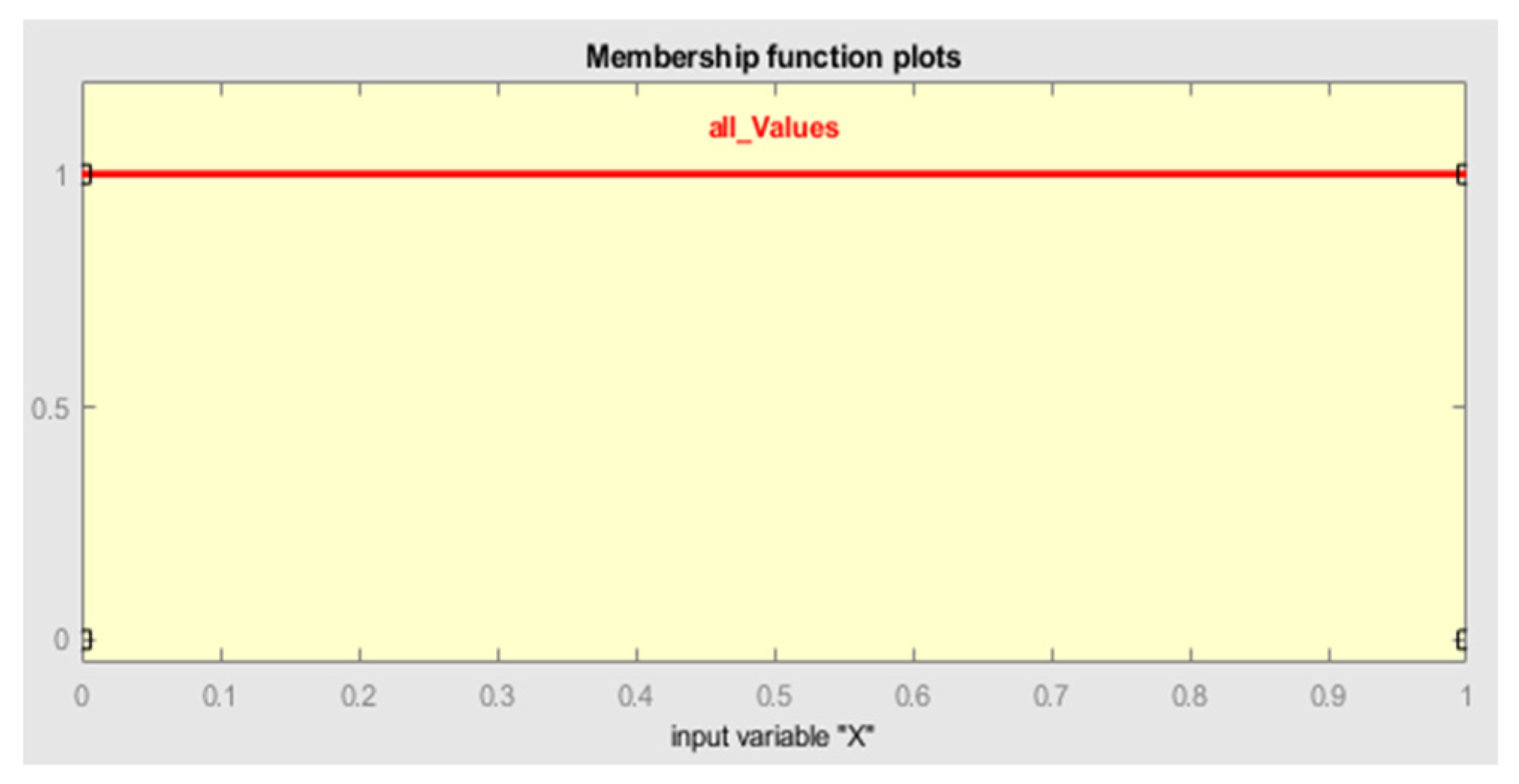

Since the system operates on normalized input values, it can process signals with varying amplitude levels. The fuzzification procedure applied to the three Lorenz state variables is detailed in

Figure 11.

As shown in the figure, a single membership function (all_Values) has been employed, covering all possible input values of the variable. This membership function is of the trapezoidal type (‘trapmf’) and is defined with boundary values of [0, 0, 1, 1].

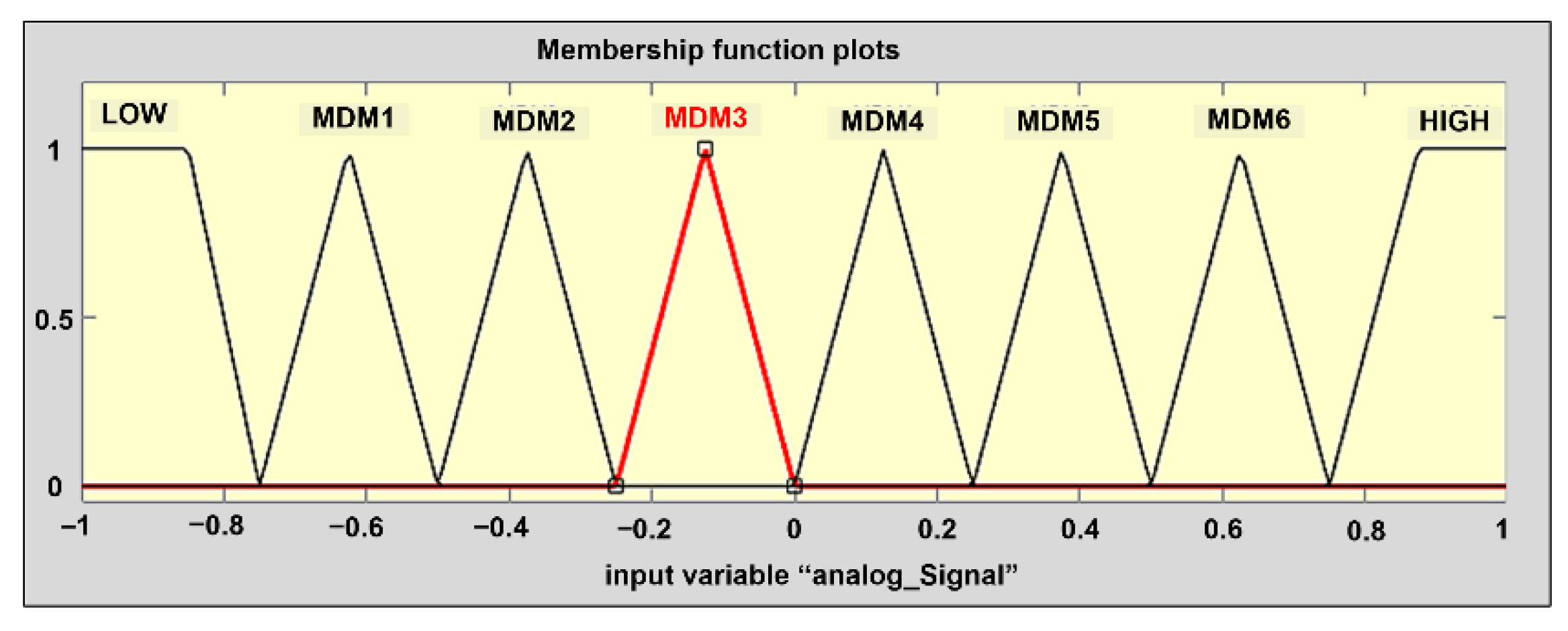

The membership function defined for the analog signal input, however, exhibits a significantly higher density compared to those of the other input variables, as shown in

Figure 12.

The types and boundary values of the membership functions directly influence the characteristics of the encryption process. The membership functions employed in this study, along with their corresponding boundary values, are presented in

Table 1.

In this study, the outputs of the fuzzy logic system were constructed using a Sugeno-type structure. The Sugeno approach enables the controlled generation of the desired linear combination in the output expression. For this reason, the Sugeno method was deemed suitable for achieving the intended mixing behaviour of the carrier signal.

Figure 13 presents the Sugeno output membership functions defined for eight different mixing configurations.

The type of Sugeno output functions was selected as ‘linear’, and their corresponding values are presented in

Table 2.

The rule base of the Sugeno fuzzy inference system is constructed using a signal-dependent thresholding strategy. The chaotic variables are dynamically mixed according to the instantaneous voltage levels of the information signal. Since the normalized input oscillates within the range of [−1, 1], this interval is partitioned into eight discrete threshold levels. This specific configuration is chosen to facilitate a high-resolution coupling between the signal’s amplitude and the chaotic dynamics, ensuring that the encryption logic adapts to the input signal’s phase. The selection of eight rules serves as a baseline design to investigate the feasibility of signal-driven variable mixing. This modular structure also allows the number of thresholds to be adjusted in future studies to evaluate different security performance levels of the carrier signal.

For fuzzy logic to be applicable, rules must be defined. In this study, eight rules are defined as

If (AS is LOW)then (CS is MIX_1),

If (AS is MDM1)then (CS is MIX_2),

If (AS is MDM2)then (CS is MIX_3),

If (AS is MDM3)then (CS is MIX_4),

If (AS is MDM4)then (CS is MIX_5),

If (AS is MDM5)then (CS is MIX_6),

If (AS is MDM6)then (CS is MIX_7),

If (AS is HIGH)then (CS is MIX_8).

The carrier signal is formed as a complex structure that incorporates the Lorenz variables. The information signal is then combined with this carrier through the AM technique. In this way, the resulting carrier not only embeds the data but also enhances security by making unauthorized extraction difficult, while effectively concealing the transmitted information within the chaotic domain.

Under identical experimental conditions, a 100 Hz sinusoidal signal with peak amplitude of 1 V was encrypted using the AM-based scheme depicted in

Figure 10.

Figure 14 illustrates the one-dimensional CS–X, CS–Y, and CS–Z plots obtained from a 2.5 s simulation.

4. Achievement of Encryptions

Both encryption methods were simulated in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, and visual results were observed. The CS signals obtained after encryption were visualized on the oscilloscope screens, and then the traces of the encrypted signals were investigated.

In conventional AM-based chaotic encryption, a critical problem is evident, as shown in

Figure 15: the modulating signal is clearly observable. Reducing the amplitude of the data signal may diminish these fluctuations on the carrier, but it introduces increased noise sensitivity. In contrast, the FRBSI-based AM encoding system completely suppresses the modulating signal, leaving no discernible trace, as shown in

Figure 15. Therefore, significant amplitude reduction in the data signal is unnecessary, and its magnitude remains well above the noise level.

After visual inspection, the CS signals obtained from both encryption methods were examined mathematically by performing Fourier analysis. This analysis enabled us to investigate whether the frequency component of the encrypted 100 Hz sine wave remains observable, as shown in

Figure 16. The figure demonstrates that the CS signal generated by the conventional method clearly reveals its embedded 100 Hz component after the Fourier analysis. However, in the proposed method, the 100 Hz encrypted component remains indistinct and is hidden in the frequency spectrum.

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 clearly demonstrate the unreliability of the conventional AM-based encryption method, whereas the proposed approach shows that the 100 Hz sinusoidal signal is completely hidden and, consequently, unobservable.

To comprehensively evaluate the statistical security of the proposed encryption scheme, Histogram analysis, Information Entropy, and Correlation Coefficient analysis were jointly employed. This combined evaluation provides a robust assessment of whether the encrypted signal is statistically distinguishable from noise.

First, histogram analysis was performed on the FRBSI-based CS signal, generated by encrypting a 100 Hz sinusoidal message with a chaotic carrier at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz. The amplitude values were normalized to a maximum of 1, and the histogram was represented as a probability density function (PDF). The resulting distribution exhibits a widely spread and smooth structure without sharp or narrow dominant peaks typically associated with periodic signals. This indicates that the statistical amplitude characteristics of the original sinusoidal message are effectively concealed,

Figure 17.

Second, the randomness of the encrypted signal was quantitatively measured using Shannon Information Entropy computed from the amplitude histogram with 256 quantization levels Equation (7).

where

: the probability of the i-th amplitude bin,

: Equal to 256.

The proposed scheme achieves an entropy value of approximately 7.1 bits, which is close to the theoretical maximum of 8 bits for an 8-bit quantized signal. This high entropy value confirms that the encrypted signal possesses a high degree of uncertainty and randomness, while the slight deviation from the ideal limit is attributed to the deterministic nature of chaos-based modulation.

Finally, Correlation Coefficient analysis was conducted to examine statistical dependence within the encrypted signal, Equation (8).

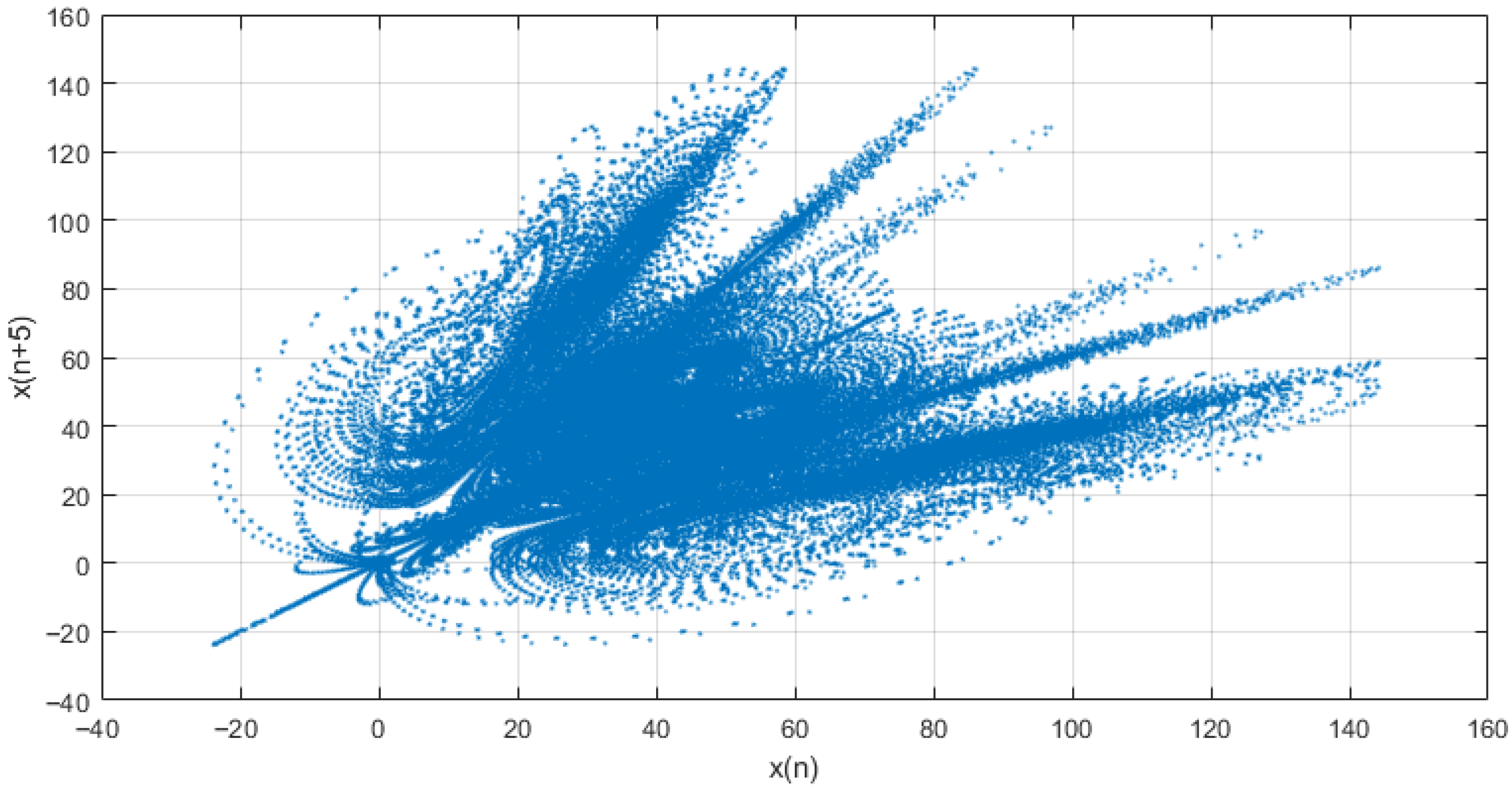

To avoid oversampling-induced correlation, correlation coefficients were calculated using delayed sample pairs rather than strictly adjacent samples. The obtained correlation values are close to zero, and the corresponding scatter plots show no discernible linear patterns,

Figure 18.

The delayed-sample correlation coefficient of the FRBSI-based CS signal is approximately 0.33, which is significantly lower than that of the original sinusoidal signal. This indicates that although a small amount of deterministic dependency remains due to the AM structure and chaotic carrier, the statistical correlation of the message signal is largely suppressed.

Overall, the combined results of histogram, entropy, and correlation analyses consistently demonstrate that the proposed FRBSI-based chaotic encryption scheme effectively conceals the statistical features of the original message signal. The encrypted waveform exhibits noise-like behavior and is statistically indistinguishable from random noise, thereby providing strong resistance against statistical and information-theoretic attacks.

5. Implementation of the Proposed Encryption Method

This section provides a detailed description of the implementation process for the proposed FRBSI-based chaotic encryption. The implementation consists of two stages: transmitter and receiver. In the transmitter stage, a 100 Hz sinusoidal input signal is encrypted via FRBSI, resulting in the synthesis of CS, IS, and SS signals. At the receiver stage, the 100 Hz sine wave is recovered from the CS, IS, and SS signals.

5.1. Transmitter Implementation

The signal considered within the scope of the encryption process is a sinusoidal waveform exhibiting time-dependent periodic variation, with its parameters selected as a 100 Hz frequency and a peak voltage of 1 V. The encryption structure of the sinusoidal signal based on the FRBSI method is presented in

Figure 19.

As shown in

Figure 19, the process comprises three output variables: the encrypted signal (CS), the synchronization signal (SS), and the rule-information signal (IS). Within the encryption process, SS is required to ensure that the Lorenz variables on the receiver side can be generated in synchrony with those on the transmitter side. For this purpose, one of the Lorenz state variables on the transmitter side is selected as the state variable SS.

The chosen state variable should be the one that most strongly influences the chaotic signal generation process. This selection shortens the synchronization time between the chaotic signals at the transmitter and receiver sides. Therefore, in this study, the Lorenz-Y state variable is chosen as the SS signal.

As shown in

Figure 19, an additional output generated alongside the encrypted signal is the IS signal. The IS signal contains the rule-order information corresponding to the output expression produced by the fuzzy logic system. This enables the fuzzy logic system on the receiver side to determine which rule combination should be used to decrypt the incoming CS signal.

Here, the fuzzy logic system generates two output signals: the IS signal and the CS, as illustrated in

Figure 19. The output rules of the fuzzy logic system are based on the Sugeno approach. Within the framework of the study, the output rules are defined as follows:

If (AS is LOW)then (CS is MIX_1) (IS is RUL_1),

If (AS is MDM1)then (CS is MIX_2) (IS is RUL_2),

If (AS is MDM2)then (CS is MIX_3) (IS is RUL_3),

If (AS is MDM3)then (CS is MIX_4) (IS is RUL_4),

If (AS is MDM4)then (CS is MIX_5) (IS is RUL_5),

If (AS is MDM5)then (CS is MIX_6) (IS is RUL_6),

If (AS is MDM6)then (CS is MIX_7) (IS is RUL_7),

If (AS is HIGH)then (CS is MIX_8) (IS is RUL_8).

In the expressions above, the variables beginning with ‘MIX’ represent the Sugeno-based fuzzy output membership functions of the crypto signal,

Table 2, whereas those beginning with ‘RUL’ correspond to the Sugeno-based fuzzy output membership functions of the IS signal,

Table 3.

5.2. Receiver Implementation

The CS, SS, and IS signals are input to the receiver system from the transmitter, as shown in

Figure 20. The output of the receiver system is the decrypted sinusoidal signal, AS, used in the encryption process.

Here, the receiver system, as the transmitter system, also includes a Lorenz-based chaotic signal generator. In practice, the Lorenz signals generated at the receiver may differ from those at the transmitter in terms of the initial values of the state variables and the start time of the algorithm. These differences can lead to synchronization mismatches between the chaotic signals produced at the transmitter and receiver. To address this issue, the SS signal from the transmitter is used as a reference signal at the receiver. By incorporating the SS signal into a closed-loop negative feedback circuit, the Lorenz chaotic system at the receiver is compelled to generate a signal synchronized with that of the transmitter, as shown in

Figure 21.

The fuzzy logic system has five input signals and one output signal. The output signal is generated based on the Sugeno method. The IS input, with respect to the “co.states.Y” inputs, is defined as shown in

Figure 11. For the CS input, the fuzzification method is presented in

Figure 22 below.

The output is defined using the Sugeno function method, as illustrated in

Figure 13. The fuzzy logic system generates the correct AS signal based on the signal at the IS input. The Lorenz signals generated at the receiver side are subtracted from the CS signals with the help of the fuzzy logic system to obtain a pure sinusoidal signal. The output expressions of the fuzzy logic system are defined in the form of Sugeno rules as

If (IS is LOW) then (AS is RUL_1),

If (IS is MDM1)then (AS is RUL_2),

If (IS is MDM2)then (AS is RUL_3),

If (IS is MDM3)then (AS is RUL_4),

If (IS is MDM4)then (AS is RUL_5),

If (IS is MDM5)then (AS is RUL_6),

If (IS is MDM6)then (AS is RUL_7),

If (IS is HIGH) then (AS is RUL_8).

The Sugeno functions are selected as ‘linear,’ and their definitions are provided below in

Table 4.

The AS estimation results obtained by the receiver system are presented in

Figure 23 and

Figure 24.

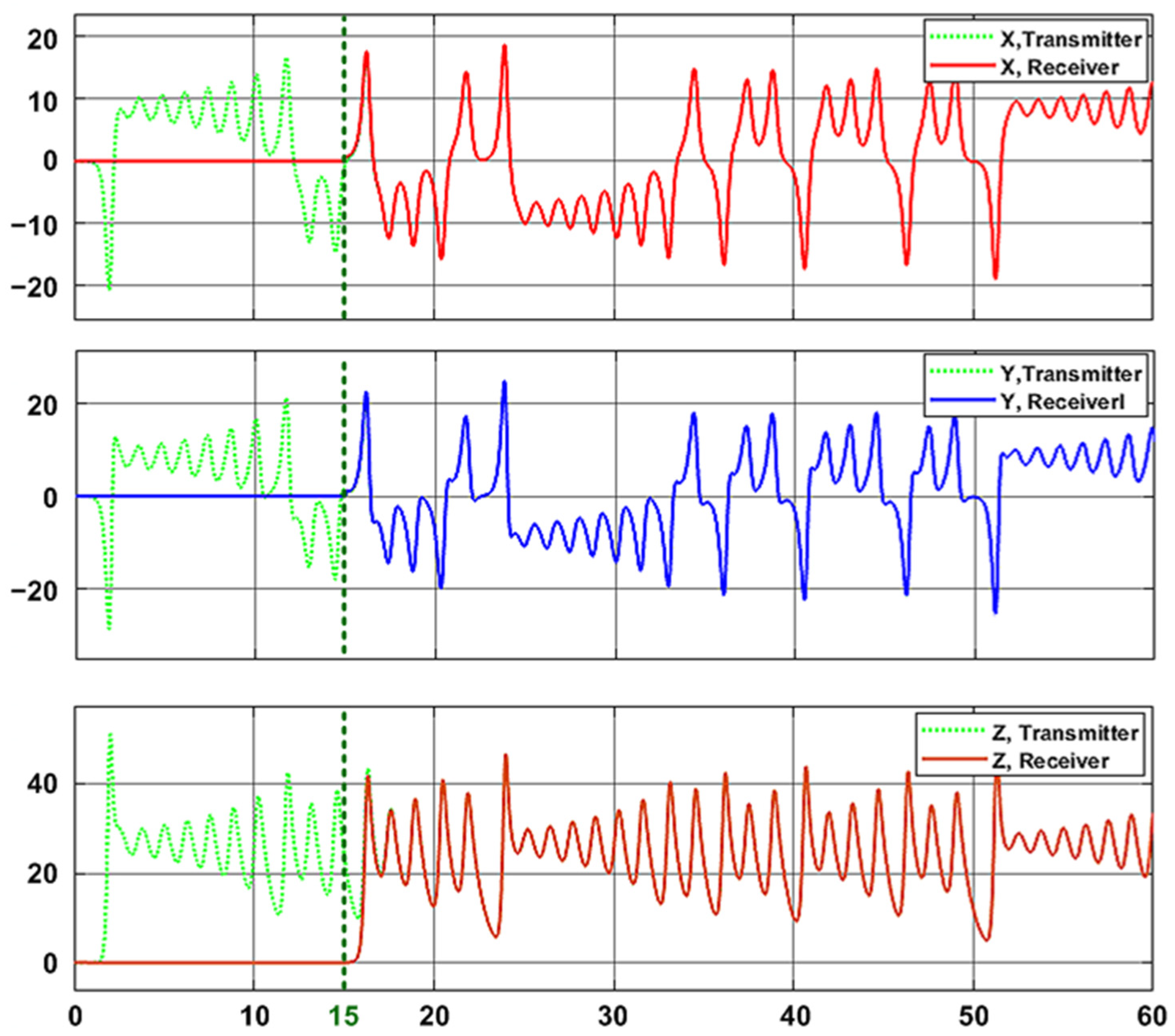

As shown in the graph above, the Lorenz chaotic system on the receiver side is not executed during the first 15 s,

Figure 23. Then, by using the “T.Lorenz.y” signal from the transmitter as the reference input of the P controller, the receiver-side Lorenz output signals are produced synchronously with the output signals on the transmitter side, as shown in

Figure 23.

As observed, the x and y variables synchronize almost immediately, whereas the z variable experiences a synchronization delay of approximately 2.5 s, as shown in

Figure 23. This delay in the “Lorenz.z” state variable also adversely affects the decryption process,

Figure 24. Consequently, the sinusoidal signal is not obtained immediately at the 15th second; instead, the final sinusoidal signal is generated gradually with a delay of approximately 2.5 s, as shown in

Figure 24.

Security of the proposed system is further reinforced by the high sensitivity of the fuzzy Sugeno rule base. The decryption algorithm requires an exact match of the rule parameters; even a single-bit discrepancy prevents the reconstruction of the original signal. A representative example of this sensitivity is shown in

Figure 25, where a slight modification to the vector of Rule 4, changed from [0

−1 0 −1 1 0] to [0

0 0 −1 1 0], results in a total failure of the decryption process. This characteristic ensures that the Sugeno rules function as a robust structural key, protecting the system against unauthorized access and brute-force attempts.

The proposed cryptosystem exhibits extreme sensitivity to its temporal and structural parameters. Specifically, a mere 10% mismatch between the transmitter’s sampling period and the receiver’s discrete-time Lorenz chaotic system results in fuzzy-based decryption failure, as shown in

Figure 26. A similar performance degradation is observed when there is a lack of synchronization in the fuzzy membership function parameters. As shown in

Figure 27, a disruption of the MDM2 membership function bounds, shifting from the nominal set [−0.5, −0.375,

−0.25] to [−0.5, −0.375,

−0.35], renders the decrypted data unrecoverable. These results confirm that even small parameter deviations lead to a complete loss of chaotic synchronization, providing robust resistance to unauthorized decryption attempts.

6. Dynamic Key-Space Expansion via Signal-Coupled Chaotic Transformations

The proposed algorithm utilizes a dynamic transformation mechanism that goes beyond static masking techniques. In this framework, chaotic variables undergo a series of non-linear transformations, including summation, subtraction, and scaling with fixed coefficients, to generate the final encryption sequence. These transformations are not predefined; instead, they are dynamically governed by the voltage thresholds of the normalized information signal.

A core innovation of this methodology is the coupling between the information signal’s spectral properties and the chaotic dynamics. Specifically, the frequency of the message signal (

) directly modulates the transformation velocity (

) of the chaotic variables. This creates a signal-dependent encryption environment where the transformation laws evolve in real-time. Mathematically, the encrypted signal S(t) can be represented as a function of the synchronized chaotic state C(t), the original signal m(t), and a time-varying transformation operator

:

where the operator

is sensitized to the instantaneous amplitude and frequency of m(t). This approach ensures that the “secret key” is not merely a set of initial parameters but a dynamic, signal-coupled state. Consequently, even if an attacker identifies the underlying chaotic attractor, the absence of the signal-induced transformation parameters renders the decryption process computationally infeasible, effectively expanding the functional key space to resist advanced cryptanalysis.

7. Sensitivity and Differential Attack Analysis

To evaluate the sensitivity of the proposed algorithm to slight changes in the plaintext, the Number of Pixels Change Rate (NPCR) and Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI) metrics were adapted for signal data as follows:

where

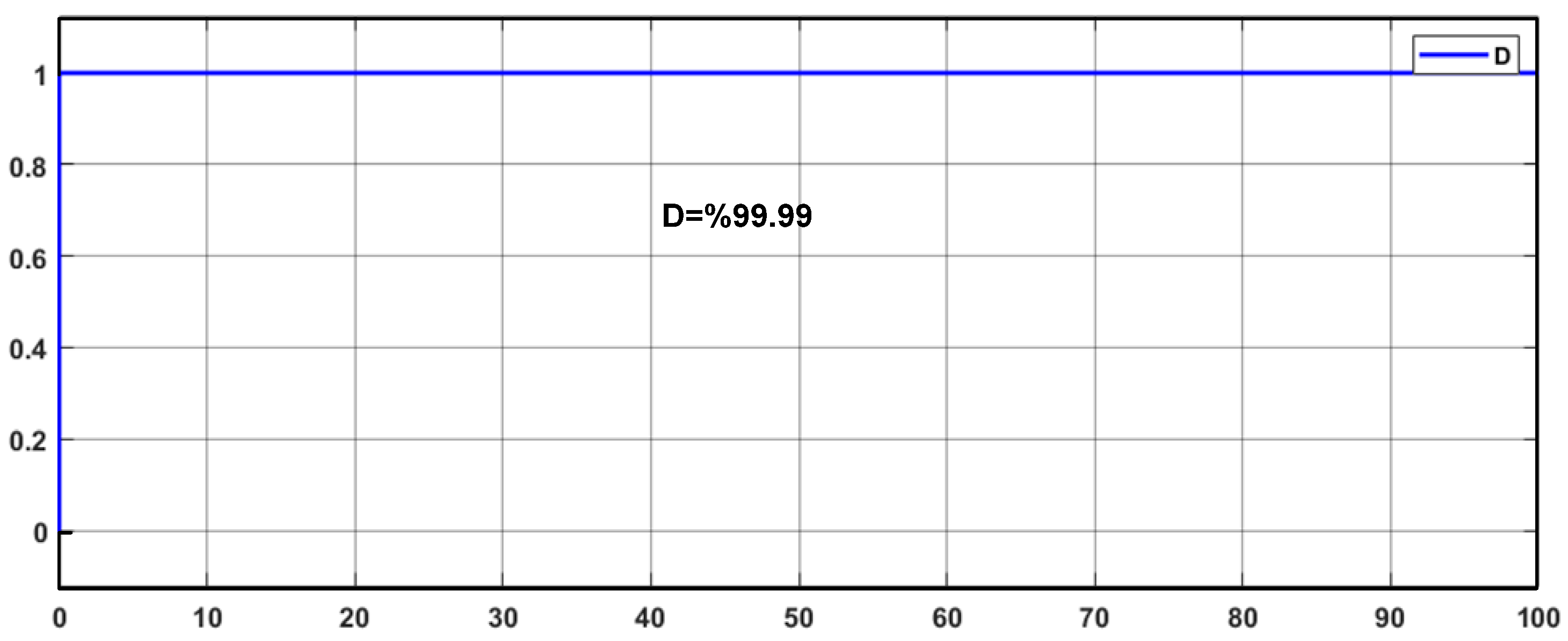

For the NPCR sensitivity analysis, two encrypted waveforms (C1 and C2) were compared. The original plaintext frequency of 100.000 Hz was perturbed to 100.0001 Hz for the second ciphertext, while maintaining a constant peak amplitude of 1.0 for both cases,

Figure 28.

To further visualize the sensitivity of the encryption process, the difference mapping D is presented in

Figure 29. As the figure illustrates, the sample-wise divergence between the two ciphertexts is uniformly distributed, validating the algorithm’s high sensitivity to plaintext perturbations. This spatial distribution of D confirms the robustness of the system against differential cryptanalysis.

8. Conclusions

In this study, a sophisticated chaos-based encryption framework was developed as a robust alternative to conventional cryptographic approaches. The findings demonstrate that utilizing a single chaotic state in amplitude modulation is insufficient for high-security applications. By integrating all state variables of the Lorenz chaotic system into the modulation process through a Fuzzy Rule-Based Sugeno Inference (FRBSI) mechanism, a significantly more complex and unpredictable carrier signal was achieved.

Experimental results, validated through both time-domain oscilloscope observations and frequency-domain Fourier analysis, confirm that the proposed FRBSI-based method effectively conceals the information signal. Unlike traditional techniques where the information signal may leak into the carrier’s envelope, our method ensures total masking, leaving no discernible patterns in either domain. Furthermore, the security of the algorithm was rigorously quantified using statistical metrics. The achieved NPCR and UACI values demonstrate a high sensitivity to infinitesimal changes in the plaintext, indicating exceptional resistance against differential cryptanalysis. Additionally, Key Sensitivity tests revealed that even a single-bit discrepancy in the receiver-side Sugeno rule base renders the decryption process unsuccessful, confirming the system’s robustness against brute-force attacks.

The numerical stability of the proposed framework was ensured by the Euler-Forward method, and the entire architecture was successfully implemented in the MATLAB-Simulink environment. The successful synchronization of the Lorenz, information, and encryption signals allowed for high-fidelity recovery of the original message at the receiver. In conclusion, the FRBSI-based encryption method provides a lightweight, secure, and highly adaptive solution for digital communication. Future research will focus on extending this framework to more complex data types, such as real-time image and audio encryption, to further explore its potential in multi-media security.