Dendro-AutoCount Enhanced Using Pith Localization and Peak Analysis Method for Anomalous Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

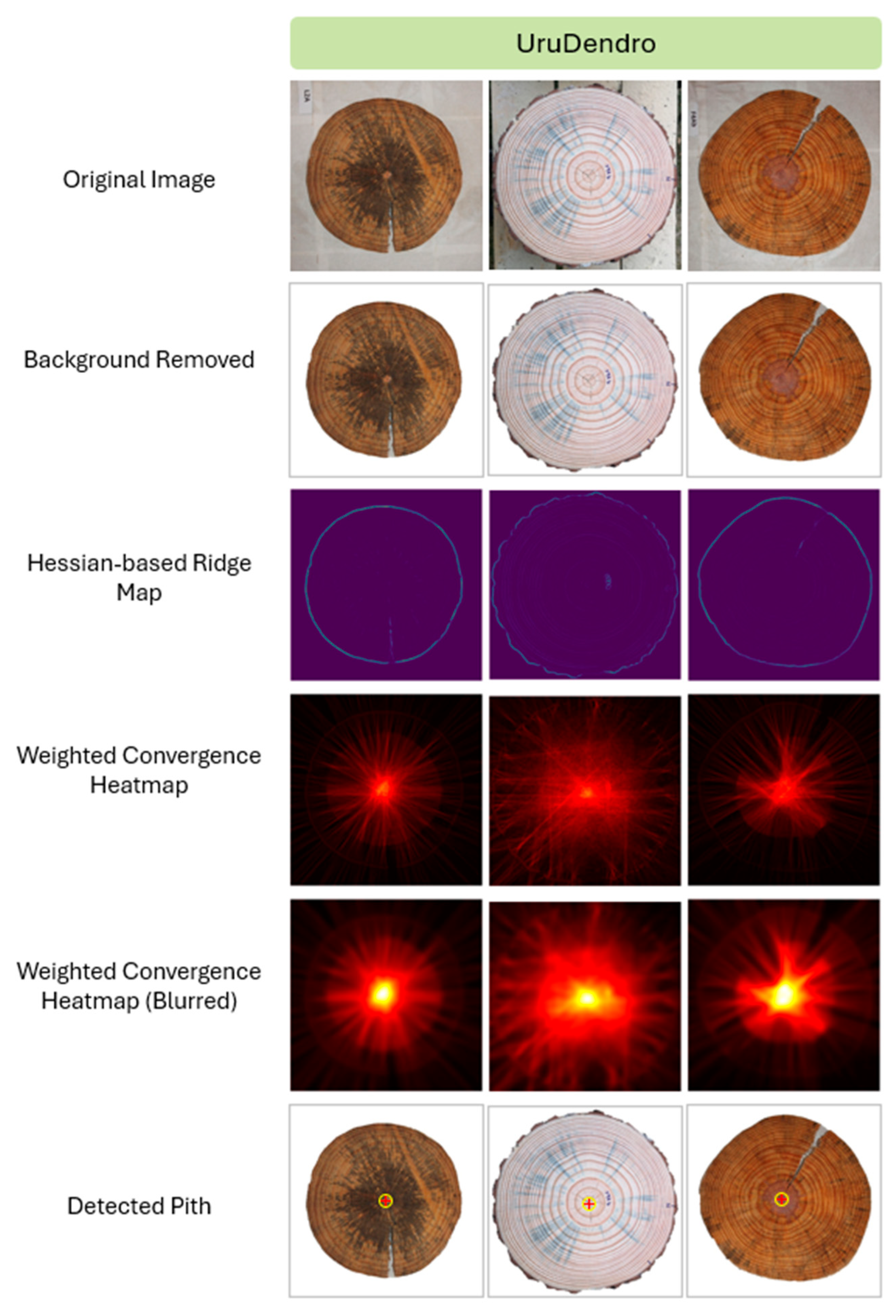

- Hessian-based pith localization: this work abandons the circularity assumption. It proposes a hybrid framework that adapts Hessian-based ridge detection. It combines gradient analysis (using the Scharr filter) with weighted radial voting. This treats tree rings as topographic ridges rather than circles, allowing for accurate pith detection even in highly distorted or asymmetric samples.

- Peak analysis via ROI extraction: To handle localized defects (e.g., mold or knots), the image is segmented into four directional Regions of Interest (north, east, south, and west). For each ROI, intensity profiles are generated, smoothed with a Gaussian filter, and subjected to peak detection to identify tree rings as signal maxima. Subsequently, the tree ring detection is refined using constraints such as minimum distance and peak prominence.

- Statistical tree ring consolidation: Finally, we implement an outlier removal mechanism using a 1.5 times the standard deviation threshold across the four ROI images. This ensures that if a specific sector is damaged or anomalous, it is excluded from the final calculation, and the result is averaged from the remaining valid directions to enhance accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition

2.2. Image Preprocessing

2.3. Pith Localization

2.3.1. Hessian-Based Ridge Detection

2.3.2. Gradient Analysis

2.3.3. Weighted Radial Voting

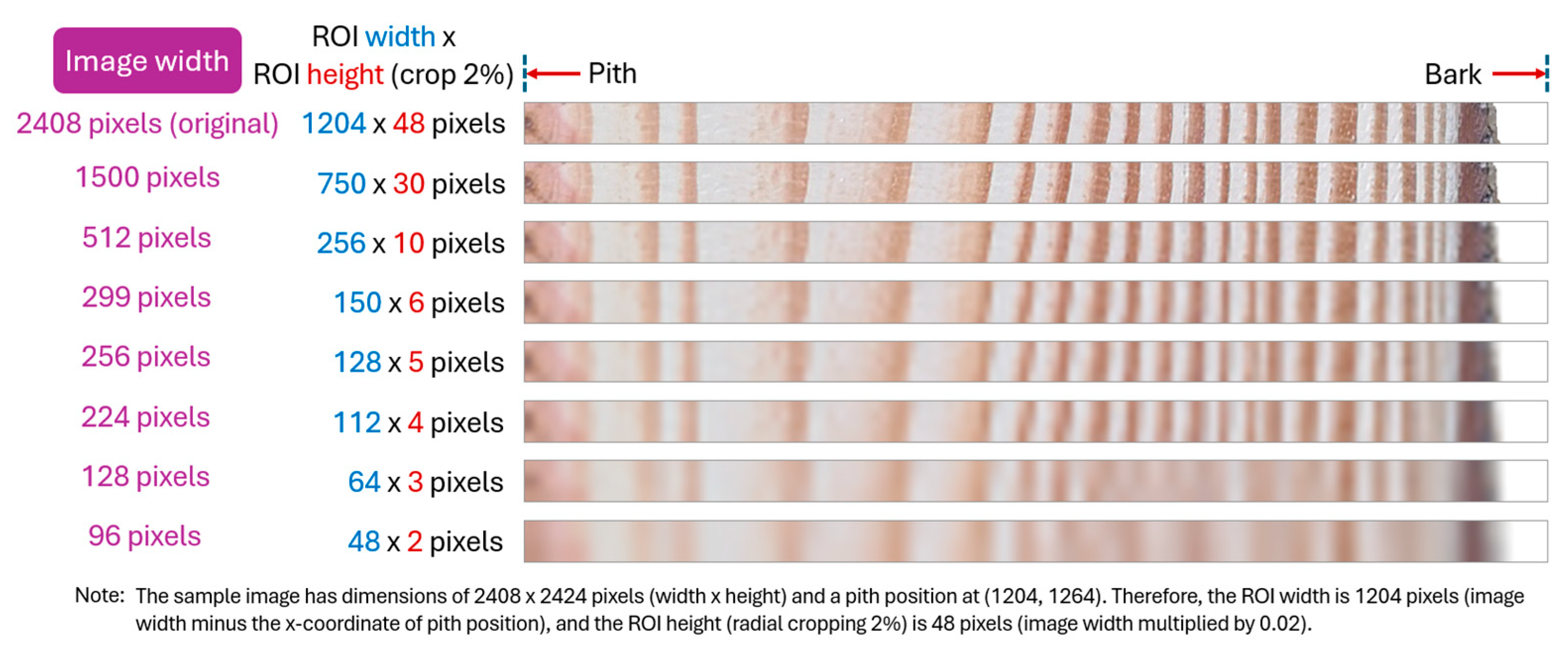

2.4. Region of Interest Extraction

2.5. Ring Detection

2.5.1. Intensity Profile Generation

2.5.2. Signal Smoothing

2.5.3. Peak Detection

2.6. Ring Count Consolidation

2.7. Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Detected Pith Localization Efficiency

3.2. The Tree Ring Counting Efficiency

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Divya, K.; Kaur, S. A study on tree rings: Dendrochronology using image processing. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1022, 012115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decelle, R.; Ngo, P.; Debled-Rennesson, I.; Mothe, F.; Longuetaud, F. Directional filter for tree ring detection. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods, Rome, Italy, 24–26 February 2024; pp. 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latte, N.; Beeckman, H.; Bauwens, S.; Bonnet, S.; Lejeune, P. A novel procedure to measure shrinkage-free tree-rings from very large wood samples combining photogrammetry, high-resolution image processing, and GIS tools. Dendrochronologia 2015, 34, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makela, K.; Ophelders, T.; Quigley, M.; Munch, E.; Chitwood, D.; Dowtin, A. Automatic tree ring detection using Jacobi sets. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.08691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabija’nska, A.; Danek, M.; Barniak, J.; Piórkowski, A. Towards automatic tree rings detection in images of scanned wood samples. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 140, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, T.; Su, X.; Wu, B.; Min, Z.; Tian, Y. A tree ring measurement method based on error correction in digital image of stem analysis disk. Forests 2021, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingning, S.; Wei, X.; Qijing, L.; Sher, S. MtreeRing: An R package with graphical user interface for automatic measurement of tree ring widths using image processing techniques. Dendrochronologia 2019, 58, 125644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdthongmee, W. A comparative study of the effectiveness of using popular DNN object detection algorithms for pith detection in cross-sectional images of parawood. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habite, T.; Abdeljaber, O.; Olsson, A. Automatic detection of annual rings and pith location along Norway spruce timber boards using conditional adversarial networks. Wood Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 461–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabija’nska, A.; Danek, M. DeepDendro- A tree rings detector based on a deep convolutional neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 150, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poláčcek, M.; Arizpe, A.; Hüther, P.; Weidlich, L.; Steindl, S.; Swarts, K. Automation of tree-ring detection and measurements using deep learning. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 2233–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ko, C.; Kim, D. Method for detecting tree ring boundary in conifers and broadleaf trees using Mask R-CNN and linear interpolation. Dendrochronologia 2023, 79, 126088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Huang, Y.; Benes, B.; Warner, C.C.; Gazo, R. Automated tree ring detection of common Indiana hardwood species through deep learning: Introducing a new dataset of annotated images. Inf. Process. Agric. 2024, 11, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, M.; Hitschfeld-Kahler, N.; Mery, D. Robust tree-ring detection. In Advances in Image and Video Technology (PSIVT 2007), Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Mery, D., Rueda, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Xi, Y.; Harada, K.; Zhang, Y.; Nagashima, K.; Qiao, Z. Improved Hough transform and total variation algorithms for features extraction of wood. Forests 2021, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.-Q.; Hua, S.-H.; He, Y.; Wang, K.-N.; Zhou, D.; Wang, H. Automatic myotendinous junction identification in ultrasound images based on junction-based template measurements. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, M.; Pourghassem, H. An active contour model using matched filter and Hessian matrix for retinalvessels segmentation. Turk. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2022, 30, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N.L.H.; Kor, A.-L.; Ang, M.C.; Rondeau, E.; Georges, J.-P. Image filtering techniques for object recognition in autonomous vehicles. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2024, 30, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, B.; Gao, W.; Zheng, W.; Yang, G. Newly designed identifying method for ice thickness on high-voltage transmission lines via machine vision. High Volt. 2021, 6, 904–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y. Focusing on the roots of range: Real-time 3D point cloud semantic segmentation with edge enhancement and heights delity. J. Frankl. Inst. 2025, 362, 107954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichal, H.; Passarella, D.; Lucas, C.; Profumo, L.; Casaravilla, V.; Rocha Galli, M.N.; Ambite, S.; Randall, G. UruDendro, a public dataset of 64 cross-section images and manual annual ring delineations of Pinus taeda L. Ann. For. Sci. 2025, 82, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichal, H.; Casaravilla, V.; Ludmila, P.; Christine, L.; Diego, P.; Gregory, R. UruDendro2, a Public Dataset of 53 Cross-Section Images and Manual Annual Ring Delineations of Pinus taeda L. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15652452 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Marichal, H.; Blanco, J.; Passarella, D.; Randall, G. UruDendro4: A Benchmark Dataset for Automatic Tree-Ring Detection in Cross-Section Images of Pinus taeda L. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15653340 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Norell, K.; Borgefors, G. Estimation of pith position in untreated log ends in sawmill environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 63, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennel, P.; Borianne, P.; Subsol, G. An automated method for tree-ring delineation based on active contours guided by DT-CWT complex coefficients in photographic images: Application to Abies alba wood slice images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 118, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofheinz, F.; Langner, J.; Beuthien-Baumann, B.; Oehme, L.; Steinbach, J.; Kotzerke, J.; van den Ho, J. Suitability of bilateral ltering for edgepreserving noise reduction in PET. EJNMMI Res. 2011, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Dogra, A.; Goyal, B. Comparative analysis of bilateral filter and its variants for magnetic resonance imaging. Open Neuroimaging J. 2020, 13, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.; Kornprobst, P.; Tumblin, J.; Durand, F. Bilateral filtering: Theory and applications. Founda. Trends Comput. Graph. Vis. 2009, 4, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuanmeesri, S. Utilization of multi-channel hybrid deep neural networks for avocado ripeness classification. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 14862–14867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuanmeesri, S.; Poomhiran, L.; Ploydanai, K. Improving the prediction of rotten fruit using convolutional neural network. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2021, 69, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, N.Z. The improvement of 1D Gaussian blur filter using AVX and OpenMP. In Proceedings of the 2022 22nd International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 27 November–1 December 2022; pp. 1493–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poomhiran, L.; Meesad, P.; Nuanmeesri, S. Improving the recognition performance of lip reading using the concatenated three sequence keyframe image technique. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 6986–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Lv, S. Research on data cleaning method of metal material corrosion fatigue test data. IOP Conf. Ser. J. Phys. 2023, 2468, 012097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhang, R.; Tong, T. When Tukey meets Chauvenet: A new boxplot criterion for outlier detection. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marichal, H.; Passarella, D.; Randall, G. CS-TRD: A cross sections tree ring detection method. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2305.10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillert, A.; Resente, G.; Anadon-Rosell, A.; Wilmking, M.; von Lukas, U.F. Iterative next boundary detection for instance segmentation of tree rings in microscopy images of shrub cross sections. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14540–14548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morino, K.; Minor, R.L.; Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Brown, P.M.; Hughes, M.K. Bimodal cambial activity and false-ring formation in conifers under a monsoon climate. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenmaier, M.; Garnot, V.S.F.; Wegner, J.D.; von Arx, G. Towards ROXAS AI: Automatic multi-species ring boundaries segmentation as regression in anatomical images. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1516635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Total Images | Total Rings | Tree Age (Years) | Image Width (Pixels) | Average Pixel per Ring Width | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Mean | ||||

| UruDendro [15] | 64 | 1221 | 14 to 24 | 2877 | 897 | 174.86 | 38.73 | 93.75 |

| UruDendro2 [22] | 53 | 1151 | 19 to 23 | 3672 | 2267 | 142.57 | 81.41 | 110.16 |

| UruDendro4 [23] | 102 | 1930 | 16 to 22 | 5712 | 1317 | 282.19 | 58.82 | 173.47 |

| ) | SD | 1.5SD | 1.53SD | 1.6SD | 1.8SD | 2.0SD | 3.0SD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th. | Th. | Th. | Th. | Th. | Th. | ||||||||||

| 21, 29, 30, 31 | 4.57 | 29.50 | 8.50 | 6.86 | 30 | 7.00 | 30 | 7.32 | 30 | 8.23 | 30 | 9.15 | 28 | 13.72 | 28 |

| 22, 29, 30, 31 | 4.08 | 29.50 | 7.50 | 6.12 | 30 | 6.25 | 30 | 6.53 | 30 | 7.35 | 30 | 8.16 | 28 | 12.25 | 28 |

| 23, 29, 30, 31 | 3.59 | 29.50 | 6.50 | 5.39 | 30 | 5.50 | 30 | 5.75 | 30 | 6.47 | 30 | 7.19 | 28 | 10.78 | 28 |

| 24, 29, 30, 31 | 3.11 | 29.50 | 5.50 | 4.66 | 30 | 4.76 | 30 | 4.97 | 30 | 5.60 | 29 | 6.22 | 29 | 9.33 | 29 |

| 25, 29, 30, 31 | 2.63 | 29.50 | 4.50 | 3.94 | 30 | 4.02 | 30 | 4.21 | 30 | 4.73 | 29 | 5.26 | 29 | 7.89 | 29 |

| 26, 29, 30, 31 | 2.16 | 29.50 | 3.50 | 3.24 | 30 | 3.31 | 30 | 3.46 | 30 | 3.89 | 29 | 4.32 | 29 | 6.48 | 29 |

| 27, 29, 30, 31 | 1.71 | 29.50 | 2.50 | 2.56 | 29 | 2.61 | 29 | 2.73 | 29 | 3.07 | 29 | 3.42 | 29 | 5.12 | 29 |

| 28, 29, 30, 31 | 1.29 | 29.50 | 1.50 | 1.94 | 30 | 1.98 | 30 | 2.07 | 30 | 2.32 | 30 | 2.58 | 30 | 3.87 | 30 |

| 29, 29, 30, 31 | 0.96 | 29.50 | 0.50 | 1.44 | 30 | 1.46 | 30 | 1.53 | 30 | 1.72 | 30 | 1.91 | 30 | 2.87 | 30 |

| 30, 29, 30, 31 | 0.82 | 30.00 | 0.00 | 1.22 | 30 | 1.25 | 30 | 1.31 | 30 | 1.47 | 30 | 1.63 | 30 | 2.45 | 30 |

| Efficiency | UruDendro | UruDendro2 | UruDendro4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SD (pixels) | 2.42 | 2.55 | 2.61 |

| MDE (pixels) | 3.38 | 9.59 | 10.34 |

| RMSE (pixels) | 3.94 | 9.72 | 10.46 |

| (pixels) | 17 | 45 | 26 |

| Calculated distance threshold (T) | 7 | 21 | 12 |

| Hit rate (%) | 92.19 (@T = 7), 100.00 (@T ≥ 11) | 90.57 (@T = 12), 100.00 (@T ≥ 13) | 90.20 (@T = 12), 100.00 (@T ≥ 15) |

| Method | Detection Rate (%) | MDE (Pixels) | SD (Pixels) |

|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv3 [8] | 80.50 | 6.42 | 10.68 |

| SSD MobileNet [8] | 89.20 | 5.12 | 9.27 |

| Proposed method | 91.06 | 4.65 | 7.02 |

| Efficiency | UruDendro | UruDendro2 | UruDendro4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ME (rings) | −0.031 | 0.038 | −0.029 |

| MAE (rings) | 0.094 | 0.113 | 0.108 |

| RMSE (rings) | 0.395 | 0.389 | 0.357 |

| MAPE (%) | 0.5320 | 0.4960 | 0.5870 |

| R2 | 0.9936 | 0.8924 | 0.9659 |

| Precision | 0.9985 | 0.9967 | 0.9978 |

| Recall | 0.9962 | 0.9984 | 0.9963 |

| F1-score | 0.9972 | 0.9975 | 0.9970 |

| 0.9951 | 0.9948 | 0.9938 | |

| 0.9375 | 0.9057 | 0.9020 |

| Method | Dataset | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | RMSE | Execution Time (Seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-TRD [35] | Kennel | 0.9700 | 0.9700 | 0.9700 | 2.40 | 11.10 |

| Proposed method | Kennel | 1.0000 | 0.9730 | 0.9863 | 2.42 | 9.92 |

| CS-TRD [21,35] | UruDendro | 0.9500 | 0.8600 | 0.8900 | 5.27 | 17.30 |

| Proposed method | UruDendro | 0.9985 | 0.9951 | 0.9964 | 0.47 | 16.21 |

| CS-TRD [35] | UruDendro (test) | 0.9400 | 0.8800 | 0.9100 | 3.00 | 18.00 |

| INBD [35] | UruDendro (test) | 0.7500 | 0.8400 | 0.7900 | 5.70 | 7.50 |

| Image Size (Pixels) | UruDendro | UruDendro2 | UruDendro4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 0.9962 | 0.9984 | 0.9963 |

| 1500 × 1500 | 0.9951 | 0.9965 | 0.9953 |

| 512 × 512 | 0.9885 | 0.9904 | 0.9890 |

| 299 × 299 | 0.9793 | 0.9825 | 0.9800 |

| 256 × 256 | 0.9734 | 0.9754 | 0.9742 |

| 224 × 224 | 0.9684 | 0.9709 | 0.9693 |

| 128 × 128 | 0.9487 | 0.9503 | 0.9492 |

| 96 × 96 | 0.9003 | 0.9042 | 0.9018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nuanmeesri, S.; Poomhiran, L. Dendro-AutoCount Enhanced Using Pith Localization and Peak Analysis Method for Anomalous Images. Mathematics 2026, 14, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010094

Nuanmeesri S, Poomhiran L. Dendro-AutoCount Enhanced Using Pith Localization and Peak Analysis Method for Anomalous Images. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuanmeesri, Sumitra, and Lap Poomhiran. 2026. "Dendro-AutoCount Enhanced Using Pith Localization and Peak Analysis Method for Anomalous Images" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010094

APA StyleNuanmeesri, S., & Poomhiran, L. (2026). Dendro-AutoCount Enhanced Using Pith Localization and Peak Analysis Method for Anomalous Images. Mathematics, 14(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010094