Customized Product Design and Cybersecurity Under a Nash Game-Enabled Dual-Channel Supply Chain Network

Abstract

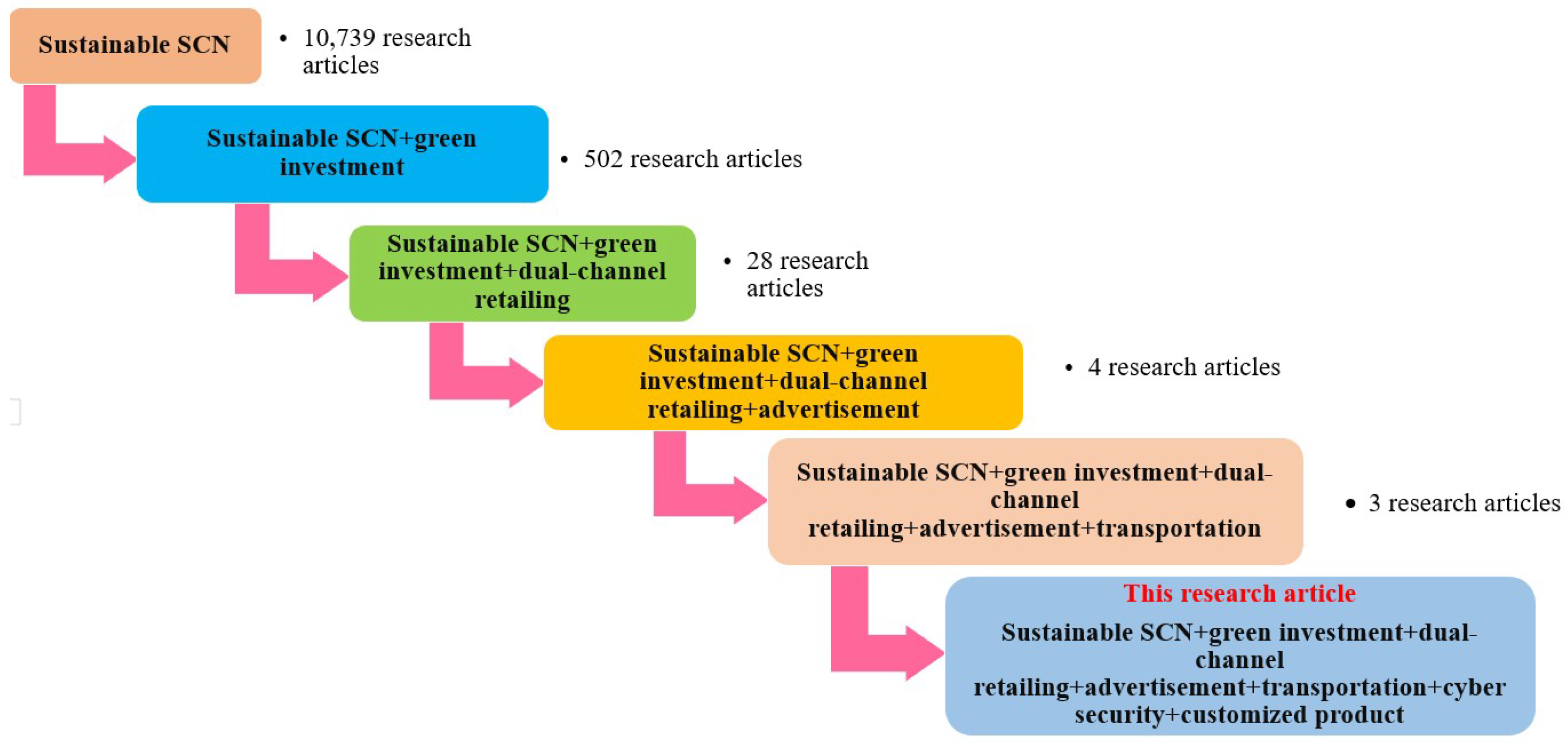

1. Introduction

1.1. Aims and Objectives

- As e-commerce and digital platforms are expanding exponentially, retailers are faced with disastrous issues in data protection and customer trust; hence, it is imperative to create effective cybersecurity strategies. At the same time, customers want more personalized experiences, and businesses are challenged to create customized products with their own individual priorities in focus, resulting in increased customer satisfaction and loyalty.

- This study is driven by the pressing global imperative for eco-friendly business practices; the challenge is the integration of green innovation in production and distribution to ensure environmental and economic gains. Effective advertising strategies also play a crucial role in influencing the minds of consumers and conveying the value of customized and sustainable products. Finally, dual-channel retailing helps all types of customers buy products according to their own priorities and put businesses ahead in the competitive market.

- By combining these dimensions, this study aspires to advance theory and offer managerial suggestions for creating a secure, sustainable, and customer-oriented retail atmosphere in order to survive and thrive in the green and digital economy.

1.2. Research Questions

- What will be the profit of the retailer, manufacturer, and supply chain if it has cybersecurity issues for online and offline channel? Can the proposed policy provide more profit than either the online cybersecurity issue or offline cybersecurity issue alone?

- In the face of green innovation and advertisement issues, will the customized product dual-channel strategy be beneficial for both the player and the supply chain?

- What is the best dual-channel retailing strategy for maximizing the profit using green innovation, advertisement, cybersecurity, and customized products?

1.3. Contribution of This Study

- To run businesses efficiently and smoothly in today’s competitive and globalized market, supply chain members provide the service of customized products based on customer preferences to give customer satisfaction through online and offline channels.

- To develop brand trust and avoid interrupted operations, supply chain members invest in strong security measures, which ensure that the customer can collaborate easily and happily in the near future.

- To develop environmental growth, the manufacturer makes green products. The manufacturer and retailer transport products using railway transportation, which is more eco-friendly than other transportation systems.

- To increase sales and enhance brand reputation, advertising services are provided by supply chain members.

1.4. Orientation

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influence of Customized Product Under Dual-Channel Channel

2.2. Impact of Advertisement and Selling Price Driven Demand in Supply Chain

2.3. Effects of Cybersecurity in Supply Chain

2.4. Transportation in Supply Chain

2.5. Effect of Green Innovation Within Supply Chain

3. Problem Definition, Notation, and Assumptions

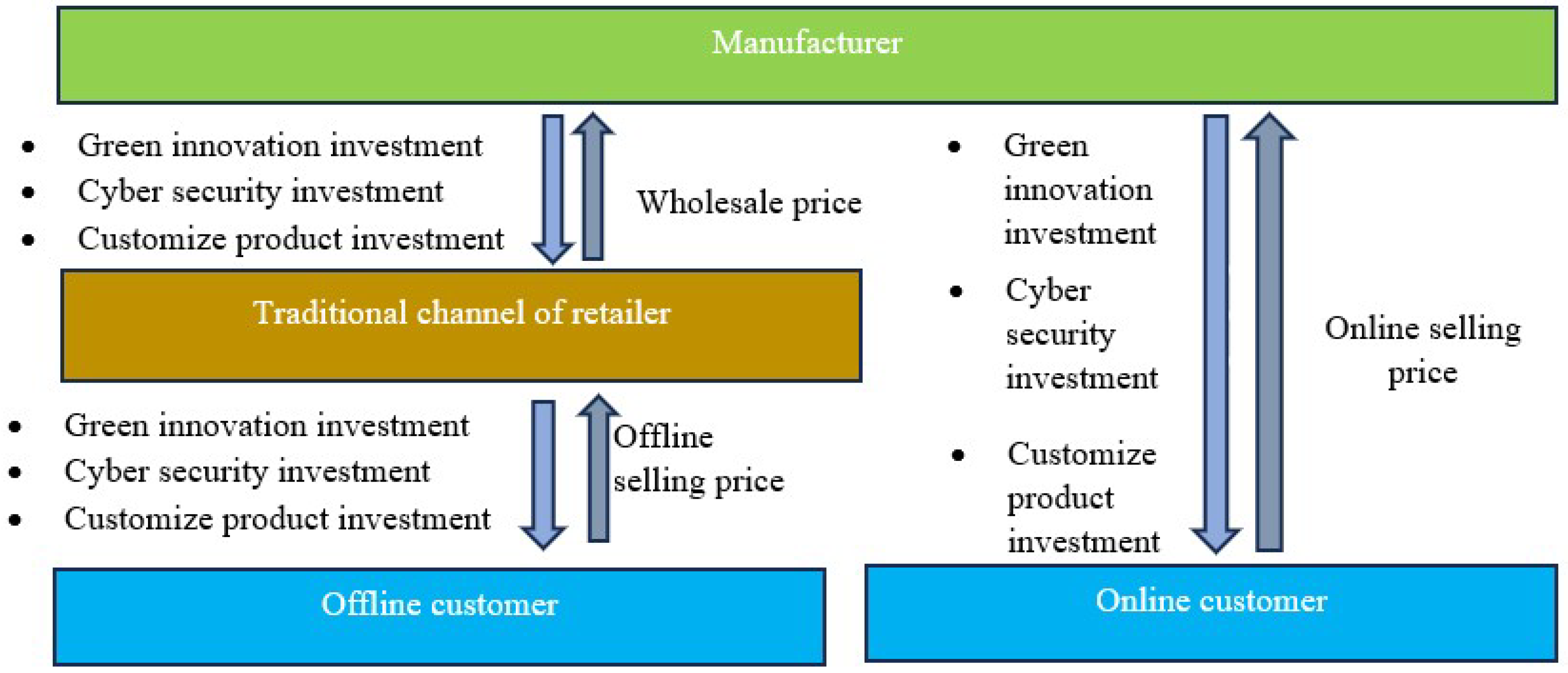

3.1. Problem Definition

3.2. Notation

3.3. Assumptions

4. Mathematical Model Formulation

4.1. Manufacturer’s Model

4.1.1. Revenue

4.1.2. Cybersecurity Investment

4.1.3. Customized Product Design Investment

4.1.4. Green Innovation Investment

4.1.5. Transportation Cost

4.1.6. Total Profit of the Manufacturer

4.2. Retailer’s Model

4.2.1. Revenue from Selling

4.2.2. Advertisement Investment

4.2.3. Purchasing Cost

4.2.4. Transportation Cost

4.2.5. Cybersecurity Investment

4.2.6. Customize Product Design Investment

4.2.7. Total Profit of the Retailer

4.3. Total Profit of the SCN

5. Solution Methodology

5.1. CP Method

| Algorithm 1: Algorithm to find the global numerical solution in CP method | |

| Step 1. | Give all parameter’s values and set the loop counter i. |

| Step 2. | Set the initial values of parameters. |

| Step 3. | Evaluate from Equation (17) utilizing the values of Step 2. |

| Step 4. | Evaluate from Equation (18) utilizing the values of Step 3. |

| Step 5. | Evaluate from Equation (19) utilizing the values of Step 4. |

| Step 6. | Evaluate from Equation (20) utilizing the values of Step 5. |

| Step 7. | Evaluate from Equation (21) utilizing the values of Step 6. |

| Step 8. | Evaluate from Equation (22) utilizing the values of Step 7. |

| Step 9. | Evaluate from Equation (23) utilizing the values of Step 8. |

| Step 10. | Evaluate from Equation (24) utilizing the values of Step 9. |

| Step 11. | Evaluate from Equation (25) utilizing the values of Step 10. |

| Step 12. | Evaluate from Equation (26) utilizing the values of Step 11. |

| Step 13. | Set all the above-proposed steps utilizing the amended values of , , , , , , , , , and . Until the values of , , , , , , , , , and from and i become the same, repeat Steps 3 to 12. |

| Step 14. | Calculate the total profit of SCN by substituting the values of , , , , , , , , , and into Equation (16). This is the maximum profit, and , , , , , , , , , and are the optimal solutions. |

| Step 15. | Stop. |

5.2. VN Method

| Algorithm 2: Algorithm to find the global solution for the manufacturer in VN method | |

| Step 1. | Give all parameter’s values and set the loop counter. |

| Step 2. | Set the initial value = 1, = 0.2, = 0.2, = 0.2, = 0.6, and = 0.6. |

| Step 3. | Evaluate from Equation (27),utilizing the values of Step 2. |

| Step 4. | Evaluate from Equation (28),utilizing the values of Step 3. |

| Step 5. | Evaluate from Equation (29),utilizing the values of Step 4. |

| Step 6. | Evaluate from Equation (30),utilizing the values of Step 5. |

| Step 7. | Evaluate from Equation (31),utilizing the values of Step 6. |

| Step 8. | Evaluate from Equation (32),utilizing the values of Step 7. |

| Step 9. | Set the all above-proposed steps utilizing the amended values of , , , , , and . Repeat this method until the values of , , , , , and stay unchanged. |

| Step 10. | Calculate the total profit of the manufacturer by putting the values of , , , , , and , into the Equation (15). This is the optimal profit and , , , , , and , are the optimal solution. |

| Step 11. | Stop. |

| Algorithm 3: Algorithm to find the global solution for the retailer in VN method | |

| Step 1. | Give all parameter’s values and set the loop counter. |

| Step 2. | Set the initial value = 1, = 0.2, = 0.5, and = 0.5. |

| Step 3. | Evaluate from Equation (33),utilizing the values of Step 2. |

| Step 4. | Evaluate from Equation (34),utilizing the values of Step 3. |

| Step 5. | Evaluate from Equation (35),utilizing the values of Step 4. |

| Step 6. | Evaluate from Equation (36),utilizing the values of Step 5. |

| Step 7. | Set all the above-proposed steps utilizing the amended values of , , , and . Repeat this method until the values of , , , and stay unchanged. |

| Step 8. | Calculate the total profit of the retailer by substituting the values of , , , and into Equation (8). This is the optimal profit, and , , , and represent the optimal solution. |

| Step 9. | Stop. |

5.3. Comparison Between CP and VN Methods

6. Numerical Analysis

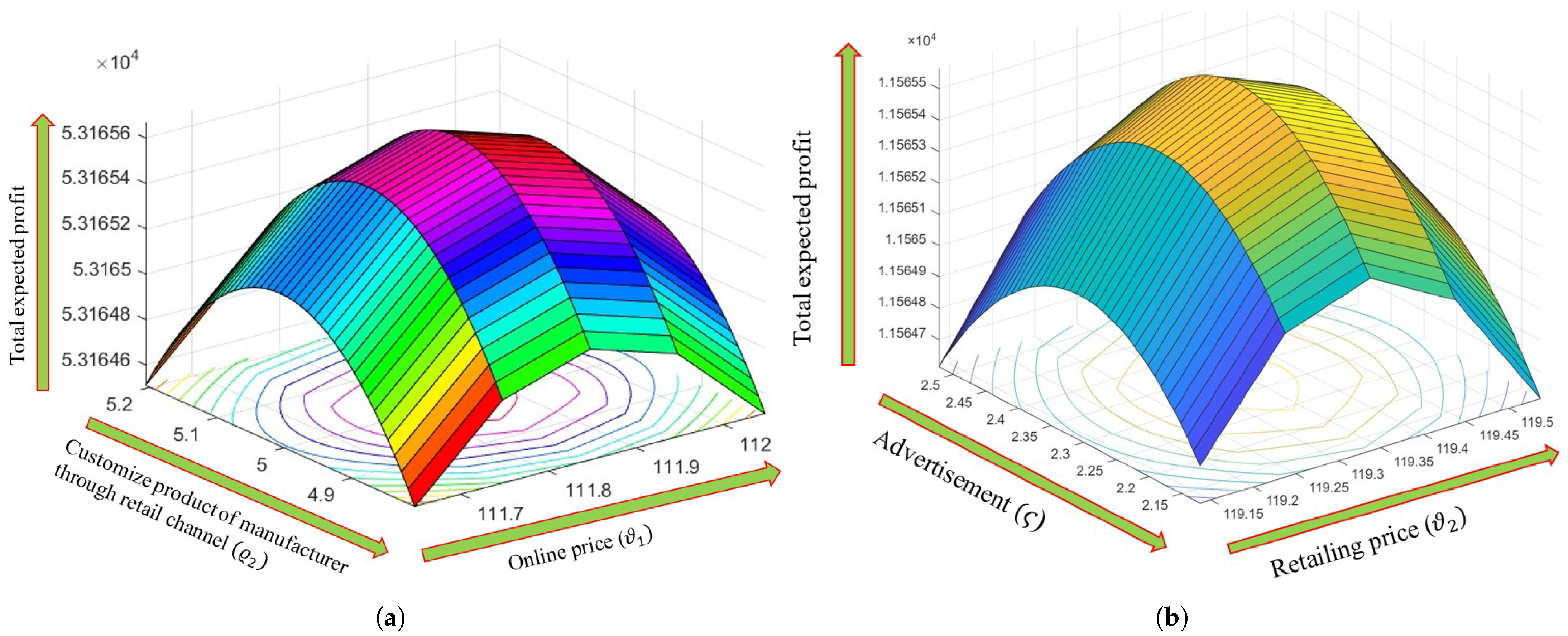

6.1. Discussion of Results

6.1.1. Example for CP Method

6.1.2. Example for VN Method

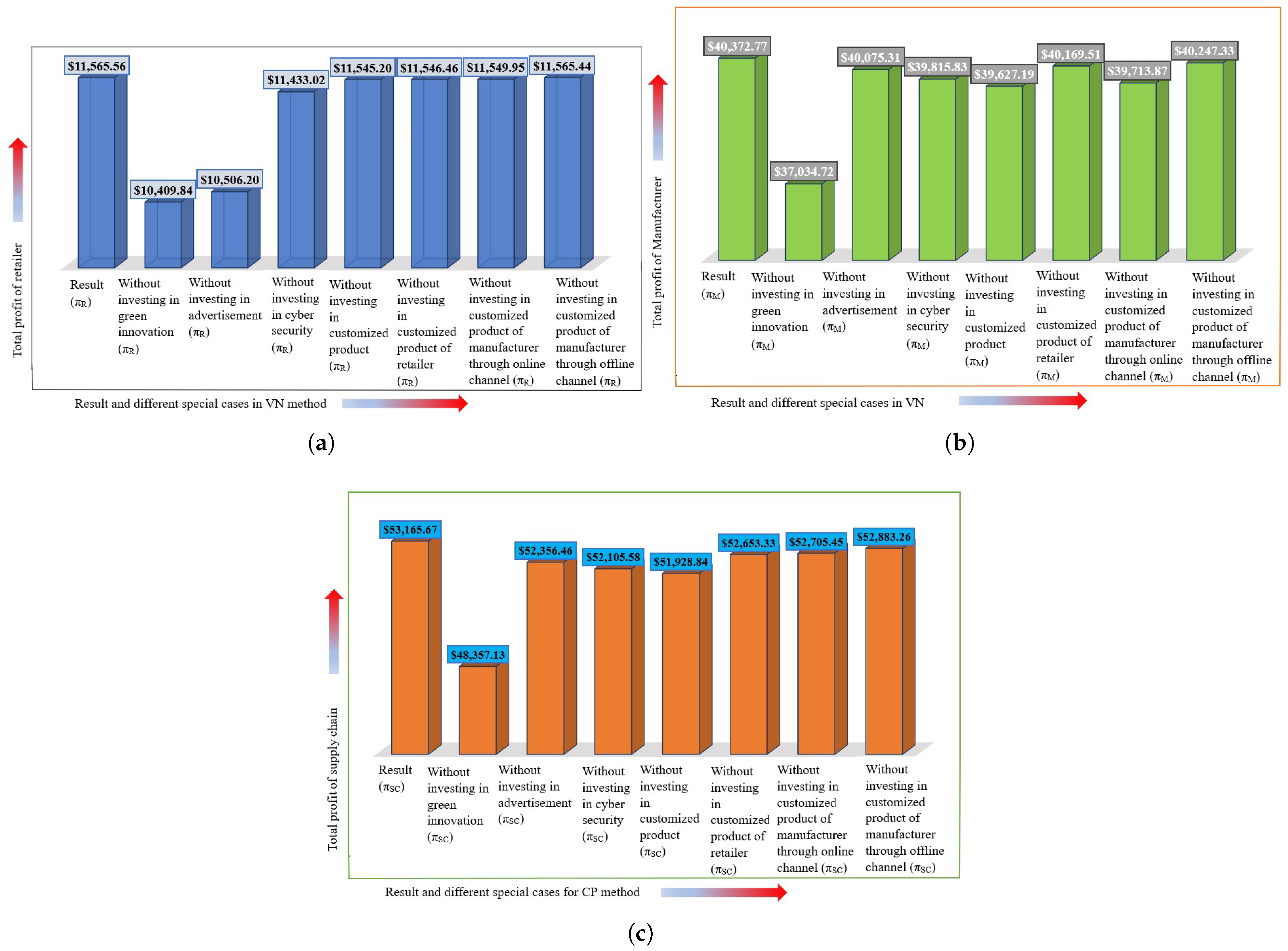

6.2. Special Cases

- I.

- Constructive Parameter Discussions for Special Cases

6.2.1. Special Case I: Without Green Innovation

- For the CP method, the value of parameter a (base demand) has a lower limit of 21 units; that is, the minimum base demand for the customized product cannot be less than 21 units when there is no green innovation. If the base demand is less than 21 units, then the SCN incurs a loss, which belongs to both of the SC players. Hence, the industrial manager should focus on the base demand so that it is not less than 21 units in the case of no green innovation.

- The value of parameter (scaling parameter for selling price) has lower and upper limits of 10.49 and 98.91, respectively. For an value of 98.91 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit becomes almost zero. For an value of 10.49, the online selling price is . For a value of either higher or lower than this, the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit increase simultaneously. In reality, customers are not interested in buying a product for a high retail price. According to the real-life situation, a lower limit has been assigned for customer satisfaction. Hence, the industrial manager should focus on the parameter .

- The values of the parameters (scaling parameter for selling price of the other channel) and (scaling parameter for advertisement in demand) have an upper limits 11.91 and 11.61, respectively. For a value 11.91, the online selling price is $272.78, but for larger increases in , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. For a value of 11.61, the online selling price and the advertisement level decision variable are $341.54 and $412, respectively, but for larger increases in the value of , the retail price and advertisement level decision variable increase excessively, imparting an effect upon the business. Hence, this is an important consideration for industrial managers.

- For the retailer in the VN method, the values of the parameters , , and have upper limits of 20.1, 49.99, and 21.7, respectively. For a value of 21.7, the values of the retail price and the advertisement level decision variable (> and , respectively) become excessively high. For an value of 20.1 or more, the advertisement and customized product design decision variables become negative, and the profit becomes less than $4.81. For a value of 20.1, the retail price becomes $261.78, but for larger increases in the value of , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. On the other hand, the investment in advertisement, customized product, cybersecurity, and profit decrease simultaneously. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the condition of these parameters.

- For the manufacturer in the VN method, the value of parameter (scaling parameter for selling price) has lower and upper limits of 10.2 and 83, respectively. The value of parameter a (base demand) has a lower limit of 51 units. If the base demand is less than 51 units, then the business incurs a loss. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the base demand. That is, when the manufacturer maximizes its profit with its own decisions, the minimum base demand is 51 units, which is more than the CP method.

- The values of parameters (scaling parameter for selling price of the other channel) and (scaling parameter for advertisement on demand) have the upper limits 12.21 and 13.98, respectively. For a value of 13.98 or more, the value of the online price and the advertisement decision variable (> and ) become excessively high.

- For an value of 83 or more, the advertisement and customized product design decision variable become negative, and profit becomes almost zero. For an value of 10.2, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values, the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase suddenly. In reality, customers will not be interested in buying a product for a high retail price. According to the real-life situation, a lower limit has been assigned for customer satisfaction.

- For a value of 12.21, the retail price becomes $332.02, but for larger increases in the value of , the retail price increases excessively. Hence, the industrial manager should analyze those parameters properly.

| Special | Case I | Special | Case II | Special | Case III | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Variables | CP Method | VN Method | CP Method | VN Method | CP Method | VN Method |

| ($/unit) | 115.47 | 110.99 | 124.22 | 118.87 | 123.60 | 118.07 |

| ($/unit) | 101.29 | 97.55 | 110.3 | 105.52 | 109.69 | 104.7 |

| − | − | 22.67 | 18.78 | 22.56 | 18.42 | |

| 8.27 | 2.2 | − | − | 8.88 | 2.3 | |

| 3.78 | 3.66 | 4.07 | 3.92 | − | − | |

| 4.48 | 3.38 | 4.75 | 3.59 | − | − | |

| 5.83 | 2.27 | 6.16 | 2.34 | − | − | |

| 6.04 | 5.86 | 6.46 | 6.23 | 6.43 | 6.2 | |

| 4.64 | 3.42 | 4.94 | 3.65 | 4.92 | 3.62 | |

| 6.11 | 2.21 | 6.48 | 2.29 | 6.46 | 2.28 | |

| Total Profit | ||||||

| ($) | − | 10,409.84 | − | 10,506.2 | − | 11,433.02 |

| ($) | − | 37,034.72 | − | 40,075.31 | − | 39,815.83 |

| ($) | 48,357.13 | − | 52,356.46 | − | 52,105.58 | − |

6.2.2. Special Case II: Without Advertisement

- For the CP method, the value of the parameter (scaling parameter for selling price) has lower and upper limits of 10.71 and 98.54, respectively. For an value of 98.54 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit becomes negligible. For an value of 10.71, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit increase simultaneously. In reality, customers are not interested in buying a product for a high retail price. Hence, the industrial manager should focus on the parameter .

- The value of the parameter a (base demand) has a lower limit of 20 units in the CP method. If the base demand is less than 20 units, then the business operates at a loss when there is no advertisement for the product. This limit is less than Case I, that is, when there is no green innovation. This implies that when the retailer does not invest in advertising, the base demand can go down than with no green innovation.

- The value of the scaling parameter for green innovation c and the scaling parameter for the selling price of the other channel have the upper limits 6.1 and 11.6, respectively. For c and values of 6.1 and 11.6, the online selling prices are $338.35 and $361.54, respectively, but for larger increases in the values of c and , the retail prices simultaneously increase excessively. Hence, the industrial manager should focus on the condition of these parameters.

- For the retailer in the VN method, the value of parameters (scaling parameter for selling price), c (scaling parameter for green innovation), and (scaling parameter for selling price of the other channel) have the upper limits 20.13, 168.91, and 11.19, respectively. For a c value of 168.91 or more, the value of the retail price (>) becomes excessively high. For an value of 20.13 or more, the green innovation and customized product design decision variable becomes negative, and the profit becomes less than $6.35. For a value of 11.19, the retail price becomes $282.76, but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the condition of these parameters.

- For the manufacturer in the VN method, the value of the scaling parameter for the selling price has lower and upper limits 10.42 and 83, respectively. For an value of 83 or more, the advertisement and customized product design decision variable become negative, and the profit is negligible. For an value of 10.42, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase simultaneously. In reality, customers will not be interested in buying a product for a high retail price. According to the real-life situation, the lower limit has been assigned for customer satisfaction. Hence, the industrial manager should focus on the parameter .

- The value of the base demand a has a lower limit of 49 units. If the base demand is less than 49 units, then the business operates at a loss. That is, when each SC player decides their decision separately in the scenario without advertisement, the base demand is less than in Case I. No green innovation scenario has more base demand than the no advertisement scenario.

- The value of the scaling parameter for green innovation c and the scaling parameter for the selling price of the other channel have the upper limits 6.99 and 11.19, respectively. For c and values of and 6.99 and 11.19, the online selling prices are $338.35 and $361.54, respectively, but for larger increases in the values of c and , the retail price increases excessively and suddenly. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the condition of these parameters.

6.2.3. Special Case III: Without Cybersecurity

- For the CP method, the value of the scaling parameter for the selling price has lower and upper limits of 10.4 and 99.3, respectively. For an value of 99.3 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit is negligible. For an value of 10.4, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit increase suddenly. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the parameter .

- The value of the base demand a has a lower limit of 11 units. If the base demand is less than 21, then the business incurs a loss. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the base demand. The values of the parameters (scaling parameter for advertisement in demand), c (scaling parameter for green innovation), and (scaling parameter for selling price of the other channel) have the upper limits 11.1, 6, and 11.6, respectively.

- For a c value of 6, the online selling price and green level decision variable are $361.49 and $832.25, but for greater increases in the value c, the retail price and green level decision variable increase suddenly and excessively. For a value of 11.1, the online selling price is $363.48, but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. For a value of 11.6, the online selling price and the advertisement level decision variable are $345.87 and $461.63, respectively, but for larger increases in the value , the retail price and advertisement level decision variable increase excessively, imparting an effect upon business. Hence, this is an important consideration for industrial managers.

- For the retailer VN method, the value of parameters (scaling parameter for selling price), (scaling parameter for advertisement in demand), c (scaling parameter for green innovation), and (scaling parameter for selling price of the other channel) have the upper limits 20.34, 21.69, 171.01, and 11.18, respectively. For an value of 20.34 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit becomes less than . For a value of 11.18, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. For a value of 21.69 or more, the investment in advertisement and the selling price become minimum values of and , respectively.

- For a c value of 171.01 units or more in the CP method, the values of the retail price and green innovation investment have become minimum values of and . This implies that the base demand is feasible at 171.01 units, but the price and green innovation will become high. Thus, when there is no cybersecurity, the base demand is higher than in Cases I and II, but it should not be more than 171.01 units.

- For the manufacturer in the VN method, the value of the parameter (scaling parameter for selling price) has lower and upper limits of 10.4 and 83.6, respectively. For an value of 83.6 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit is also near zero. For an value of 10.4, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively, all other decision variables and profit increase suddenly.

- The values of the parameters , c, and have upper limits of 13.75, 6.2, and 11.9, respectively. For a value of 11.9, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases excessively. For a c value of 6.2 or more, the values of the online price and the green level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high. For a value of 13.75 or more, the value of the online price and the advertisement level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high.

- The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 43 units in the VN method. If the base demand is less than 43 units, then the business operates at a loss. That is, decentralized decision-making has less value for the base demand of the manufacturer’s case than the retailer’s case. Hence, the effect of the retailer’s decision-making is more sensitive in the decentralized scenario without cybersecurity.

6.2.4. Special Case IV: Without Customized Product Design

- For the CP method, the value of the parameter has lower and upper limits of 10.7 and 99.5, respectively. For an value of 99.5 or more, the advertisement and customized product design decision variable become negative, and the profit becomes negligible. For an value of 10.7, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase simultaneously. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the parameter .

- The value of the base parameter a has a lower limit of 14 units. If the base demand is less than 14, then the business operates at a loss. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the base demand. This scenario has a lower base demand than Cases, I, II, and III. Thus, when there is no customized product design for SCN, the market situation is more sensitive than without green innovation, cybersecurity, or advertisement.

- The values of parameters , c, and have upper limits of 11.14, 6.12, and 11.61, respectively. For a c value of 6.12, the online selling price and green level decision variable are $359.53 and $835.72, but for larger increases in the value c, the retail price and green level decision variable increase suddenly and excessively. For a value of 11.14, the online selling price is $358.76, but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. For a value of 11.61, the online selling price and the advertisement level decision variable are $341.71 and $462.64, respectively, but for larger increases in the value , the retail price and the advertisement level decision variable increase excessively, imparting an effect upon the business.

- For the retailer in the VN method, the values of the parameters , , c, and have upper limits of 20.33, 21.64, 171.21, and 11.18, respectively. For a c value of 171.21 or more, the values of the retail price and green innovation investment have become minimum values and . For an value of 20.33 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit becomes less than .

- For a value of 11.18, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value , the retail price suddenly increases excessively. For a value of 21.64 or more, the investment in advertisement and the selling price have become minimum values of and , respectively.

- For the manufacturer, the value of parameter has lower and upper limits of 10.21 and 83.73, respectively. For an value of 83.73 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and profit becomes almost zero. For an value of 10.21, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively, all other decision variables and profit also increase suddenly.

- The values of the parameters , c, and has upper limits of 13.72, 6.31, and 12, respectively. For a value of 12, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases excessively. For a c value of 6.31 or more, the value of the online price and the green level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high. For a value of 13.72 or more, the value of the online price and the advertisement level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high.

- The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 46 units. If the base demand is less than 46, then the business incurs a loss. Thus, when the manufacturer makes a decision, the minimum base demand should not be more than 46 units. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the behavior of these parameters.

| Special | Case IV | Special | Case V | Special | Case VI | Special | Case VII | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Variables | CP Method | VN Method | CP Method | VN Method | CP Method | VN Method | CP Method | VN Method |

| ($/unit) | 123.32 | 117.69 | 124.94 | 119.02 | 125.35 | 188.48 | 125.35 | 118.85 |

| ($/unit) | 109.22 | 104.22 | 110.91 | 105.64 | 110.74 | 104.86 | 111.24 | 105.5 |

| 22.47 | 18.34 | 22.81 | 18.6 | 22.81 | 18.46 | 22.88 | 18.58 | |

| 8.86 | 2.3 | 8.98 | 2.31 | 9 | 2.32 | 9.01 | 2.31 | |

| 4.03 | 3.8 | 4.09 | 3.92 | 4.08 | 3.9 | 4.01 | 3.92 | |

| 4.71 | 3.56 | 4.77 | 3.6 | 4.77 | 3.58 | 4.78 | 3.6 | |

| 6.13 | 2.34 | 6.19 | 2.35 | 6.2 | 2.35 | 6.2 | 2.35 | |

| − | − | 6.49 | 6.24 | − | − | 6.5 | 6.24 | |

| − | − | 4.97 | 3.66 | 4.97 | 3.63 | − | − | |

| − | − | − | − | 6.52 | 2.3 | 6.53 | 2.29 | |

| Total | Profit | |||||||

| ($) | − | 11,545.2 | − | 11,546.46 | − | 11,549.95 | − | 11,565.44 |

| ($) | − | 39,627.19 | − | 40,169.51 | − | 39,713.87 | − | 40,247.33 |

| ($) | 51,928.84 | − | 52,653.33 | − | 52,705.45 | − | 52,883.26 | − |

6.2.5. Special Case V: Without Customized Product Design by the Retailer in Offline Channel

- For the CP method, the value of the parameter has lower and upper limits of 10.7 and 98.6, respectively. For an value of 98.54 or more, the advertisement and customized product design decision variable become negative, and the profit is approximately zero. For an value of 10.71, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit increase simultaneously. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the parameter .

- The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 18 units. If the base demand is less than 18, then the business operates at a loss in the CP method. Thus, the SCN players should consider the minimum base demand of 18 units when there is no customized product design by the retailer. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the base demand.

- The values of parameters , c, and have upper limits of 11.6, 6.01, and 10.99, respectively. For a c value of 6.01, the online selling price and green level decision variable are $355.82 and $833.23, but for larger increases in the value of c, the retail prices and green level decision variable increase suddenly and excessively. For a value of 10.99, the online selling prices are $356.61, but for greater increases in the value , the retail prices increase suddenly and excessively.

- For a value of 11.6, the online selling price and the advertisement level decision variable are $339.09 and $459.59, respectively, but for larger increases in the value , the retail price and advertisement level decision variable increase excessively, imparting an effect upon the business. Hence, this is important for industrial managers.

- For the retailer in the VN method, the values of the parameters , , c, and have upper limits of 20.06, 21.69, 171.01, and 11.05, respectively. For a c value of 171.01 or more, the value of the retail price and green innovation investment have become minimum values of and . For an value of 20.06 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative and profit becomes less than .

- For a value of 11.05, the retail price becomes , but for much greater increases in the value , the retail price suddenly increases excessively. For a value of 21.69 or more, the investment in advertisement and selling prices has become a minimum of and , respectively. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the condition of these parameters.

- For the manufacturer in the VN method, the values of parameters have lower and upper limits of 10.4 and 83.96, respectively. For an value of 83.96 or more, the advertisement and customized product design decision variable become negative, and the profit is also near zero. For an value of 10.4, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase simultaneously. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the parameter .

- The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 46 units. If the base demand is less than 46 units, then the business operates at a loss. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the base demand. The values of the parameters , c, and have upper limits of 11.97, 6.2, and 13.79, respectively.

| Parameters | Original Values in CP and VN Methods | CP Method | VN Method | (Retailer) | VN Method | (Manufacturer) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Parameters and Corresponding Decision Variables) | +9900% Changes in Profit the Corresponding Decision Variables | −99% Changes in Profit and the Corresponding Decision Variables | +9900% Changes in Profit the Corresponding Decision Variables | −99% Changes in Profit and the Corresponding Decision Variables | +9900% Changes in Profit the Corresponding Decision Variables | −99% Changes in Profit and the Corresponding Decision Variables | |

| Special | Case I | ||||||

| = 32, = 3.78 and 3.66 | −0.67% and = 0.08 | +16.62% and = 199.82 | − | − | −0.83% and = 0.8 | +20.76% and = 193.23 | |

| = 22, = 4.8 and 3.38 | −0.77% and = 0.13 | +9.79% and = 163.45 | − | − | −0.6% and = 0.1 | +1.81% and = 121.68 | |

| = 28, = 5.83 and 2.27 | −1.96% and = 0.21 | +15.34% and = 168.33 | −1.4% and = 0.08 | +10.72% and = 64.04 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 6.04 and 5.86 | −1.23% and = 0.17 | +17.21% and = 233.88 | − | − | −1.6% and = 0.17 | +21.58% and = 226.89 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −0.88% and = 0.1 | +22.06% and = 246.99 | − | − | −0.66% and = 0.07 | +15.87% and = 175.2 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −1.42% and = 0.18 | +19.19% and = 234.28 | −0.92% and = 0.07 | +11.39% and = 81.31 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 8.27 and 2.2 | −1.38% and = 0.08 | +36.84% and = 226.72 | −0.47% and = 0.02 | +9.98% and = 48.38 | − | − | |

| Special | Case II | ||||||

| = 32, = 3.78 and 3.66 | −0.7% and = 0.09 | +18.02% and = 216.31 | − | − | −0.84% and = 0.8 | +21.09% and = 208.25 | |

| = 22, = 4.8 and 3.38 | −0.8% and = 0.14 | +11.84% and = 173.71 | − | − | −0.68% and = 0.1 | +1.93% and = 129.75 | |

| = 28, = 5.83 and 2.27 | −1.99% and = 0.22 | +15.51% and = 178.13 | −1.57% and = 0.09 | +10.84% and = 66.28 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 6.04 and 5.86 | −1.3% and = 0.18 | +17.68% and = 251.2 | − | − | −1.6% and = 0.18 | +22.89% and = 242.71 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −0.91% and = 0.11 | +22.69% and = 264.98 | − | − | −0.71% and = 0.08 | +16.11% and = 188.47 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −1.61% and = 0.18 | +20.21% and = 249.41 | −0.94% and = 0.07 | +11.61% and = 84.41 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 22.67 and 18.78 | −8.84% and = 0.21 | +65.25% and = 226.72 | − | − | −8.15% and = 0.17 | +55.61% and = 143.2 | |

| Special | Case III | ||||||

| = 20, = 6.04 and 5.86 | −1.33% and = 0.18 | +17.26% and = 250.13 | − | − | −1.65% and = 0.17 | +22.26% and = 241.1 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −0.92% and = 0.11 | +22.39% and = 264.11 | − | − | −0.73% and = 0.08 | +16.29% and = 187.1 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −1.48% and = 0.18 | +19.89% and = 248.64 | −0.81% and = 0.06 | +9.99% and = 84.13 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 22.67 and 18.78 | −9.03% and = 0.21 | +48.68% and = 187.04 | − | − | −7.83% and = 0.17 | +53.68% and = 141.51 | |

| = 20, = 8.27 and 2.2 | −1.44% and = 0.09 | +40.63% and = 250.71 | −0.49% and = 0.02 | +10.78% and = 50.68 | − | − | |

| Special | Case IV | ||||||

| = 32, = 3.78 and 3.66 | −0.61% and = 0.07 | +18.28% and = 214.46 | − | − | −0.84% and = 0.8 | +21.36% and = 205.85 | |

| = 22, = 4.8 and 3.38 | −0.86% and = 0.14 | +10.36% and = 172.71 | − | − | −0.63% and = 0.1 | +1.97% and = 128.45 | |

| = 28, = 5.83 and 2.27 | −2.36% and = 0.22 | +16.84% and = 177.21 | −1.59% and = 0.09 | +11.84% and = 66.08 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 22.67 and 18.78 | −8.21% and = 0.2 | +56.48% and = 186.33 | − | − | −8.63% and = 0.16 | +54.95% and = 140.63 | |

| = 20, = 8.27 and 2.2 | −1.47% and = 0.09 | +38.83% and = 249.63 | −0.46% and = 0.02 | +10.11% and = 50.69 | − | − |

6.2.6. Special Case VI: Without Customized Product Design by the Manufacturer Through Online Channel

- For the CP method, the value of the parameter has lower and upper limits of 10.7 and 99.21, respectively. For an value of 99.21 or more, the advertisement and customized product design decision variable become negative, and the profit decreases towards zero. For an value of 10.71, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase simultaneously. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the parameter .

- The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 19 units. If the base demand is less than 19 units, then the business incurs a loss. Thus, when the manufacturer does not use product customization online, then the SCN base demand should be more than 19 units. Hence, industrial managers should focus on base demand.

- The values of parameters , c, and have upper limits of 11.61, 6.98, and 11.16, respectively. For a c value of 6.98, the online retail price and green level decision variable are $358.22 and $834.96, but for greater increases in the value of c, the retail prices and green level decision variable increase suddenly and excessively.

- For a value of 11.16, the online selling price is $358.01, but for larger increases in the value , the retail price suddenly increases excessively. For a value of 11.61, the online selling prices and the advertisement level decision variable are $341.98 and $458.05, respectively, but for larger increases in the value , the retail prices and advertisement level decision variable increase excessively, imparting an effect upon the business.

- For the retailer in the VN method, the values of the parameters , , c, and have upper limits of 20.09, 21.71, 169.85, and 11.19, respectively. For a c value of 169.85 or more, the value of the retail price and green innovation investment have become minimum values of and . In reality, the customer will not be interested in buying the product for a high retail price. For an value of 20.09 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and profit becomes less than .

- For a value of 11.19, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value of , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. For a value of 21.71 or more, the investment in advertisement and selling prices has become a minimum of and , respectively. In reality, the customer will not be interested in buying the product for a high retail price. According to the real-life field scenario, an upper limit has been assigned for customer satisfaction. Hence, industry managers should focus on the conditions of these parameters.

- For the manufacturer in the VN method, the value of the parameter has lower and upper limits of 10.4 and 83.45, respectively. For an value of 83.45 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit is almost zero. For an value of 10.4, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase suddenly. In reality, customers will not be interested in buying the product for a high retail price.

- The value of the parameters , c, and have upper limits of 11.96, 6.2, and 13.69, respectively. For a value of 11.96, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases excessively. For a c value of 6.2 or more, the value of the online price and the green level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high. For a value of 13.69 or more, the value of the online price and the advertisement level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high. The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 49 units. If the base demand is less than 49 units, then the business operates at a loss. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the behavior of those parameters.

| Parameters | Original Values in CP and VN Methods | CP Method | VN Method | (Retailer) | VN Method | (Manufacturer) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Parameters and Corresponding Decision Variables) | +9900% Changes in Profit the Corresponding Decision Variables | −99% Changes in Profit and the Corresponding Decision Variables | +9900% Changes in Profit the Corresponding Decision Variables | −99% Changes in Profit and the Corresponding Decision Variables | +9900% Changes in Profit the Corresponding Decision Variables | −99% Changes in Profit and the Corresponding Decision Variables | |

| Special | Case V | ||||||

| = 32, = 3.78 and 3.66 | −0.72% and = 0.09 | +18.19% and = 217.45 | − | − | −0.84% and = 0.8 | +20.89% and = 208.32 | |

| = 22, = 4.8 and 3.38 | −0.84% and = 0.14 | +10.07% and = 174.57 | − | − | −0.62% and = 0.1 | +1.9% and = 129.97 | |

| = 28, = 5.83 and 2.27 | −2.48% and = 0.23 | +16.48% and = 178.97 | −1.5% and = 0.09 | +10.91% and = 66.48 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 6.04 and 5.86 | −1.31% and = 0.19 | +18.94% and = 252.38 | − | − | −1.71% and = 0.18 | +22.86% and = 241.86 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −0.96% and = 0.11 | +24.57% and = 266.6 | − | − | −0.68% and = 0.08 | +16.02% and = 187.45 | |

| = 20, = 22.67 and 18.78 | −8.88% and = 0.21 | +61.74% and = 190.4 | − | − | −8.17% and = 0.17 | +55.61% and = 143.41 | |

| = 20, = 8.27 and 2.2 | −1.42% and = 0.09 | +40.29% and = 254.1 | −0.48% and = 0.02 | +9.98% and = 51 | − | − | |

| Special | Case VI | ||||||

| = 32, = 3.78 and 3.66 | −0.77% and = 0.09 | +17.46% and = 217.09 | − | − | −0.84% and = 0.8 | +20.9% and = 208.44 | |

| = 22, = 4.8 and 3.38 | −0.81% and = 0.14 | +10.74% and = 174.8 | − | − | −0.61% and = 0.1 | +1.91% and = 129.87 | |

| = 28, = 5.83 and 2.27 | −2.57% and = 0.23 | +16.95% and = 179.19 | −1.51% and = 0.09 | +10.9% and = 66.36 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 6.04 and 5.86 | −0.94% and = 0.11 | +24.58% and = 266.99 | − | − | −0.65% and = 0.07 | +15.96% and = 178.57 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −1.57% and = 0.19 | +21.63% and = 251.07 | −0.93% and = 0.07 | +11.47% and = 83.65 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 22.67 and 18.78 | −8.71% and = 0.21 | +54.68% and = 190.35 | − | − | −8.16% and = 0.17 | +55.63% and = 143.4 | |

| = 20, = 8.27 and 2.2 | −1.53% and = 0.09 | +39.96% and = 254.66 | −0.46% and = 0.02 | +9.93% and = 51 | − | − | |

| Special | Case VII | ||||||

| = 32, = 3.78 and 3.66 | −0.74% and = 0.09 | +17.75% and = 218.01 | − | − | −0.84% and = 0.8 | +20.89% and = 208.11 | |

| = 22, = 4.8 and 3.38 | −0.8% and = 0.14 | +10.07% and = 175.02 | − | − | −0.61% and = 0.1 | +1.92% and = 129.74 | |

| = 28, = 5.83 and 2.27 | −2.43% and = 0.22 | +17.86% and = 1679.4 | −1.56% and = 0.09 | +10.91% and = 66.27 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 6.04 and 5.86 | −1.48% and = 0.19 | +19.01% and = 252.57 | − | − | −1.9% and = 0.18 | +22.87% and = 242.58 | |

| = 28, = 4.64 and 3.42 | −1.51% and = 0.19 | +20.97% and = 251.38 | −0.88% and = 0.06 | +11.57% and = 84.4 | − | − | |

| = 20, = 22.67 and 18.78 | −9.02% and = 0.21 | +61.75% and = 191.13 | − | − | −8.11% and = 0.17 | +55.54% and = 143.06 | |

| = 20, = 8.27 and 2.2 | −1.41% and = 0.09 | +41.75% and = 255.07 | −0.48% and = 0.02 | +10.45% and = 50.91 | − | − |

6.2.7. Special Case VII: Without Customized Product Design of the Manufacturer Through Offline Channel

- For the CP method, the value of the parameter has lower and upper limits of 10.6 and 98.63, respectively. For an value of 98.63 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit is negligible. For an value of 10.6, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase simultaneously. In reality, customers will not be interested in buying the product for a high retail price.

- The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 18 units. If the base demand is less than 18, then the business operates at a loss. Hence, industrial managers should focus on the base demand. The values of the parameters , c, and have upper limits of 11.59, 6.05, and 11, respectively. For a c value of 6.05, the online selling price and green level decision variable are $357.92 and $836.06, but for larger increases in the value c, the retail prices and green level decision variable increase suddenly and excessively.

- For a value of 11, the online selling prices are $367.84, but for larger increases in the value , the retail prices increase suddenly and excessively. For a value of 11.59, the online selling prices and the advertisement level decision variable are $343.05 and $460.71, respectively, but for larger increases in the value , the retail prices and advertisement level decision variable increase excessively, imparting an effect upon the business. Hence, this is an important consideration for industrial managers.

- For the retailer in the VN method, the values of the parameters , , c, and have upper limits of 20.14, 21.71, 171.02, and 11.19, respectively. For a c value of 171.02 or more, the value of the retail price and green innovation investment have become minimum values of and . For an value of 20.14 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative and profit becomes less than .

- For a value of 11.19, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases suddenly and excessively. For a value of 21.71 or more, the investment in advertisement and the selling price become minimum values of and , respectively.

- For the manufacturer in the VN method, the value of the parameter has lower and upper limits of 10.4 and 83.8, respectively. For an value of 83.8 or more, the advertisement level decision variable becomes negative, and the profit is also near zero. For an value of 10.4, the online selling price is . For higher or lower values of , the online selling price increases excessively; all other decision variables and profit also increase suddenly.

- The values of the parameters , c, and have upper limits of 11.99, 6.18, and 13.68, respectively. For a value of 11.99, the retail price becomes , but for larger increases in the value , the retail price increases excessively. For a c value of 6.18 or more, the value of the online price and the green level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high. For a value of 13.68 or more, the value of the online price and the advertisement level decision variable (> and ) become excessively high. The value of the base demand parameter a has a lower limit of 48 units. If the base demand is less than 48 units, then the business operates at a loss. Hence, the industrial manager should focus on the behavior of those parameters.

- II.

- Nonconstructive Parameter Discussions for Special Cases

- A maximum decrease of 99% in the investment parametric values increases the profit significantly. However, for small changes such as 5% or 10%, the profit changes are insignificant.

- The results in Table 7 and Table 8 imply that an investment that is significantly higher than the optimum value reduces the relevant decision activities by the SC player. Those tasks are automatically taken care of by the associative setup. But, the investment should not be much lower than the optimized value for the stability of the result.

- For Special Case II, when there is no advertisement by the retailer, the green innovation investment parameter decreases to 90%, not to 99%. That is, without investment, green investment can be relaxed to 90% but not less than that.

- It is found that when advertisement is withdrawn from the system, it causes the maximum profit loss, −8.84%, when the green investment parameter is increased to 9900%; this is the highest among all special cases. Similarly, a −90% causes a 65.25% increase in profit, which is again the highest among all cases.

6.3. Discussions and Comparisons

6.4. Sensitivity Analysis

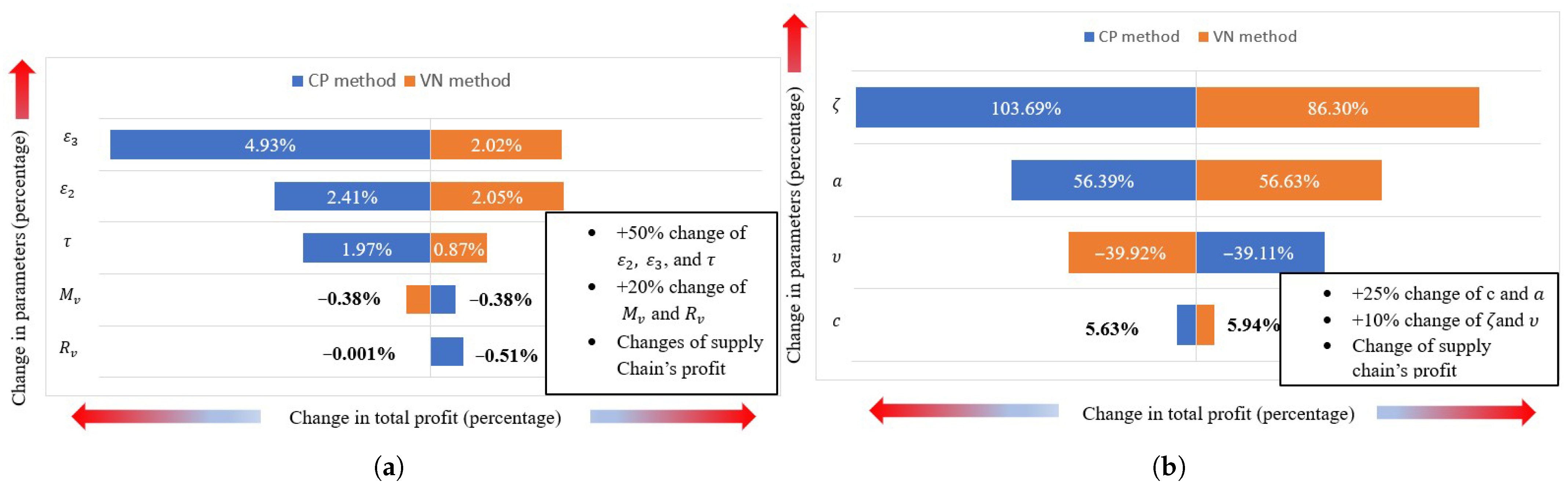

- is the most sensitive parameter, which is the cross-selling parameter. With a 10% positive change, it elevates the profits by 103.69% in the CP method and 86.3% in the VN method. For 20% changes, the VN methods provides changes, but the CP method diverges; that is, the CP method is more sensitive than VN method.

- The base demand is the next-most sensitive parameter. A decrement in a decreases profit of the supply chain by , and an increase of a increases the total supply chain profit by . The effect on the retailer’s profit is greater in offline channel than in the other cases.

- Greenness level is also a very sensitive parameter. Out of the two policies, in the CP method, the greenness level (c) has more impact on the total profit. A decrease of in greenness level decreases the total profit by , and an increase of increases the total profit by . c is more sensitive for the retailer in the VN method. The parameter c is similarly sensitive for other cases.

- The parameter related to the cybersecurity of the retailer () is more sensitive than the manufacturer’s cybersecurity parameter (). Out of these policies, the CP method shows the greatest amount of variation. A increment in and increases profit by and , respectively, whereas a decrement in and decreases the profit by and , respectively.

- is one of the most sensitive parameters, as it only varies between 10% to 20%. In the centralized and VN method, the parameter is too sensitive, decreases greater than 10% causes divergence in the results.

- The variable transportation cost of the manufacturer () is a more sensitive parameter than the variable transportation cost of the retailer (). The transportation cost of the manufacturer does not affect the retailer’s profit in the VN method. In the VN method, is much less sensitive, but in the CP Method, is a sensitive parameter. The effects of and are negligible.

| VN | CP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Changes (in %) | Retailer (%) | Manufacturer (%) | SCN (%) |

| a | % | |||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| c | % | |||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | − | − | − | |

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | − | |||

| % | − | |||

| % | − | |||

| % | − | |||

| % | − | |||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % | ||||

| % |

7. Managerial Interpretation and Insights

7.1. Business Interpretation with an Example

- An electronics manufacturer produces Bluetooth headphones. They use both online and offline channels for business.

- However, the manufacturer is not available offline in the market, especially for consumers. The manufacturer only opens sales for consumers through the online channel. The manufacturer sells Bluetooth headphones to retailers through offline channels.

- In that case, consumers can buy products according to their choice due to their ability to provide customized products. The online sales channel is operated by the manufacturer, and the offline sales channel is operated by the retailer.

- Customized product design is available for consumers from both channels, i.e., online and offline. The retailer passes the customization request to the manufacturer for the offline channel, and the manufacturer directly receives the Bluetooth headphone customization request from consumers.

- The Bluetooth headphones have a long-lasting battery that reduces the number of charges. This reduces carbon footprint for environmental sustainability.

- Since Bluetooth headphones connect through mobile or web applications, the electronics company prioritizes data protection, secure connectivity, and regular software updates for applications. This is categorized as cybersecurity, which builds consumers’ trust, reduces the risk of cyber threats, and protects both users’ and the electronics company’s reputation.

7.2. Managerial Insights

- Industrial managers are advised to open a new policy named customized product service through dual channels. This is because by satisfying a customer and meeting their needs, managers can improve the business according to the customer’s experience and taste [62]. As a result, the company can increase the brand’s value in the competitive market and can earn maximum profit.

- Industrial managers should take care of the customer’s loyalty and trust by securing the customer’s data safety and avoiding interrupted operations. Therefore, manufacturers should invest in cybersecurity to maintain brand value in the market and retain the same trust between all supply chain members.

- Embracing green practices not only minimizes environmental footprint but also enhances the brand image and customer confidence. Managers must see green endeavors as strategic investments that can generate cost savings, regulatory conformance, and competitive advantages.

- Providing both online and offline channels increases customer convenience and market coverage. Managers need to carefully balance the prices, inventories, and quality of services across the channels to prevent conflict and provide consistency. Using data from both channels offers greater consumer insight and allows personalized approaches. Properly integrating dual channels leads to stronger loyalty among customers and sustainable business growth.

- Managers need to spend advertising funds efficiently by approaching the appropriate market segments to achieve maximum return on investment. Combining traditional and digital platforms ensures broader reach and flexibility in response to shifts in consumer behavior. Finally, ongoing assessment of the effectiveness of advertisements allows refining of strategies and maintaining a long-term competitive edge.

8. Conclusions

- The study indicated that customized products enhance brand loyalty, and robust security practices minimized data breaches and business risks.

- It was found that the CP method always provided increased profit over the VN method, i.e., centralized policy is better than decentralized policy.

- When the manufacturer did not invest in green innovation, then the system’s profit reduced the most among all methods. Without investing in customized products and cybersecurity, the profit of the supply chain decreased by 2.36% in the centralized method, which is the most among the CP and VN methods.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 900 units | ; | 10; | ||

| c | 2 | /unit | |||

| /unit | |||||

| − | − | − | − |

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix C.1

Appendix C.2

References

- Monaro, M.; Bettelli, A.; Portello, G.; Pierobon, L.; Orso, V.; Caputo, A.; Campanini, M.L.; Giachetti, A.; Gamberini, L. Enhancing shopping experience in augmented reality by customizing product manipulation modalities: A customer experience study. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2025, 202, 103553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, J.D.; Borenstein, D. A framework to support customer company interaction in mass customization environments. Comput. Ind. 2004, 54, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Sao, S.; Ghosh, S.K. Smart production and photocatalytic ultraviolet (PUV) wastewater treatment effect on a textile supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 283, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safitra, M.F.; Lubis, M.; Fakhrurroja, H. Counterattacking cyber threats: A framework for the future of cyber security. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsal, O. Corporate crimes and innovation: Evidence from US financial firms. Econ. Model. 2023, 120, 106183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Basu, S.; Avittathur, B. Greening innovation, advertising, and pricing decisions under competition and market coverage. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 494, 144951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentin, A.; Forza, C.; Perin, E. Embeddedness and path dependence of organizational capabilities for mass customization and green management: A longitudinal case study in the machinery industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 169, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, G.D.; Pracejus, J.W. Customized advertising: Allowing consumers to directly tailor messages leads to better outcomes for the brand. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, I.; Yun, W.Y.; Sarkar, B. Effects of variable setup cost, reliability, and production costs under controlled carbon emissions in a reliable production system. Eur. J. Ind. Eng. 2022, 16, 371–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Ozdemir Akyildirim, O.; Yuan, K. Product customization schemes and value co-creation with platform driven C2M model. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 62, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Chauhan, A.; Sarkar, B. Sustainable biodiesel supply chain model based on waste animal fat with subsidy and advertisement. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 134806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Yuan, J.; Shu, W.; Shen, Y. Optimal product customization and cooperative advertising strategies in supply chain with social influence. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 221, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Majumder, A.; Kumar, V. The impact of adopting customization policy and sustainability for improving consumer service in a dual channel retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Maheshwari, S.; Kausar, A.; Jaggi, C.K. Sustainable retail model with preservation technology investment to moderate deterioration with environmental deliberations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 136128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, F. Will the European green deal enhance Europe’s security towards Russia? A political economy perspective. Energy Econ. 2024, 134, 107551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.M.; Wang, T.; Yen, J.C.; Chen, Y.H. Does cyber security maturity level assurance improve cyber security risk management in supply chains? Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2024, 54, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.S.; Sengupta, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Sarkar, B.; Goswami, R.T. What is the impact of demand patterns on integrated online offline and buy online pickup in store (BOPS) retail in a smart supply chain management? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, J.; Fang, J.; Sun, G. Research on optimization of distributed network security framework based on blockchain under green computing framework. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2025, 48, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Majumder, A. Involvement of carbon regulation in a smart dual channel supply chain for customized products under uncertain environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 6997–7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, D. How to design channel structures in the dual channel supply chain with sequential entry of manufacturers? Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ho, J.; Wu, G. A study on promotion with strategic two stage customized bundling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacandji, M.; Vlad, M.; Lunardo, R. The effects of retail apps on shopping well being and loyalty intention: A matter of competence more than autonomy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Yu, M. Pricing decisions in a dual channel green supply chain with product customization. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tang, Z. Should manufacturers open live streaming shopping channels? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ryu, M.H.; Lee, D.; Kim, J.H. Should a small sized store have both online and offline channels? An efficiency analysis of the O2O platform strategy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, F.; Cheng, C. ConfigRec: An efficient recommendatory configuration design method for customized products. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 82, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Motlagh, S.M.; Johari, M.; Pazari, P. Coordinating pricing, warranty replacement and sales service decisions in a competitive dual channel retailing system. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Lian, Y.; Sun, W.; Min, X.; Zhai, G. A study on the user viewing experience of implanted advertisement videos based on visual saliency. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzagoltabar, H.; Shirazi, B.; Mahdavi, I.; Khamseh, A.A. Sustainable dual channel closed loop supply chain network with new products for the lighting industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 162, 107781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y. Direct selling, agent selling, or dual format selling: Electronic channel configuration considering channel competition and platform service. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Hou, L.; Sun, Y.; Sun, M.; Sun, Y. Joint pricing, ordering and order fulfillment decisions for a dual channel supply chain with demand uncertainties: A distribution free approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 160, 107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, K.; Hoshino, T. Quantifying the short and long term effects of promotional incentives in a loyalty program: Evidence from birthday rewards in a large retail company. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Yan, R. National advertising, dual channel coordination and firm performance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Singh, S.K.; Chauhan, A. An advanced robust possibilistic chance constrained programming model for the animal fat based biodiesel supply chain network. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 47, 100884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lu, S.; Cheng, H.; Liu, X. Data driven robust optimization of dual channel closed loop supply chain network design considering uncertain demand and carbon cap and trade policy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sigroha, M.; Kumar, N.; Kumari, M.; Sarkar, B. How does the retail price maintain trade credit management with continuous investment to support the cash flow? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 83, 104116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, U.; Bhadoriya, A.; Jani, M.Y.; Sarkar, B. A generalized payment policy for deteriorating items when demand depends on price, stock, and advertisement under carbon tax regulations. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 207, 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, P.H.; Nasiri, G.R. Developing a pricing strategy and coordination in a dual channel supply chain incorporating inventory policy and marketing considerations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 185, 109607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmalek, M. Ransomware on cyber physical systems: Taxonomies, case studies, security gaps, and open challenges. Internet Things Cyber Phys. Syst. 2024, 4, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, U.H.; Singh, D.K.; Gohel, H.A. Forecasting cyber security threats landscape and associated technical trends in telehealth using Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT). Comput. Secur. 2023, 133, 103404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, D.K.; Ghosh, R. Novel interval type-2 fuzzy logic controller for improving risk assessment model of cyber security. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2018, 40, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yan, S.; Peng, S.; Hou, P. The interplay of blockchain and channel structure with consideration of cyber-security in a platform supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 197, 104045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S. Integrated framework for information security investment and cyber insurance. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2019, 57, 101173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombár, M.; Vagaská, A.; Korauš, A.; Račková, P. Application of structural equation modelling to cyber security risk analysis in the era of industry 4.0. Mathematics 2024, 12, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Habib, M.S.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Sarkar, B. Economic assessment of a serial production system with random imperfection and shortages: A step towards sustainability. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 171, 108398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabion, L.; Khorraminia, M.; Andjomshoaa, A.; Ghafouri Azar, M.; Molavi, H. A new model for assessing the impact of the urban intelligent transportation system, farmers? Knowledge and business processes on the success of green supply chain management system for urban distribution of agricultural products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Dubey, V.K.; Sarkar, B. Measure of influences in social networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 99, 106858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saen, R.F.; Karimi, B.; Fathi, A. Unleashing efficiency potential: The power of non convex double frontiers in sustainable transportation supply chains. Socio Econ. Plan. Sci. 2025, 98, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, S.U.; Asokan, P.; Sasikumar, P.; Mathiyazhagan, K.; Jerald, J. Integrated optimization of transportation, inventory and vehicle routing with simultaneous pickup and delivery in two echelon green supply chain network. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, Y.K.; Zhu, L. Strategic supply and transportation planning of a supply chain for agricultural biomass to hydrogen and syngas. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 197, 110640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Sarkar, B. An interactive fuzzy programming approach for a sustainable supplier selection under textile supply chain management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 155, 107164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yige, Z.; Haibo, K.; Min, W.; Meng, Z.; Jianzhao, L. Research on government subsidy strategy of green shipping supply chain considering corporate social responsibility. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2025, 60, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, A.; Sarkar, B. Effect of circular economy for waste nullification under a sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, O.A.; Lamba, N.K.; Jayaswal, M.K.; Mittal, M. A sustainable inventory model with advertisement effort for imperfect quality items under learning in fuzzy monsoon demand. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.S.; Omair, M.; Ramzan, M.B.; Chaudhary, T.N.; Farooq, M.; Sarkar, B. A robust possibilistic flexible programming approach toward a resilient and cost efficient biodiesel supply chain network. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Moazzam, M.; Sarkar, B.; Rehman, S.U. Synergic effect of reworking for imperfect quality items with the integration of multi period delay in payment and partial backordering in global supply chains. Engineering 2021, 7, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Singh, R.; Kumar, A.; Sarkar, B. Reduction of pollution through sustainable and flexible production by controlling by-products. J. Environ. Inform. 2022, 40, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Bliech, M.; Dahan, G. The impact of green innovation products on an organization’s social performance via green supply chain management. Green Technol. Sustain. 2025, 4, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchhait, R.; Sarkar, B. A decision making problem for product outsourcing with flexible production under a global supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 272, 109230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, B.; Sarkar, A.; Sarkar, B. Optimal decisions in a dual channel competitive green supply chain management under promotional effort. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Basu, K.; Sarkar, B. Advertisement policy for dual channel within emissions controlled flexible production system. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.K.; Pareek, S.; Tayyab, M.; Sarkar, B. Autonomation policy to control work-in-process inventory in a smart production system. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1258–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Mridha, B.; Pareek, S. A sustainable smart multi-type biofuel manufacturing with the optimum energy utilization under flexible production. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 129869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, A.; Sarkar, B. Economically independent reverse logistics of customer-centric closed-loop supply chain for herbal medicines and biofuel. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 334, 129977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.S.; Mahapatra, M.S.; Sarkar, B.; Majumder, S.K. Benefit of preservation technology with promotion and time dependent deterioration under fuzzy learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 201, 117169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Sarkar, B.; Roy, T.K. Cost-effective subsidy policy for growers and biofuels-plants in closed-loop supply chain of herbs and herbal medicines: An interactive bi-objective optimization in T-environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 100, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Nilsson, F. Enabling competitiveness in home-delivery through sustainable packaging logistics. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2025, 53, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, V.; Dasmi, C.; Nechaeva, O.; Pizzi, G.; Aiello, G. WHY do you care about me? The impact of retailers’ customer care activities on customer orientation perceptions and store patronage intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Model Type | Channel Type | Customized Product | Cybersecurity | Advertisement | Transport | Green Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhikari et al. [6] | SCM | Offline | × | × | √ | √ | √ |

| Trentin et al. [7] | SCM | × | √ | × | × | × | √ |

| Olsen and Pracejus [8] | SCM | Offline | √ | × | √ | × | × |

| Moon et al. [9] | SCM | Dual | × | √ | × | √ | √ |

| He et al. [10] | SCM | E-commerce | √ | × | × | √ | × |

| Singh et al. [11] | SCM | Offline | × | × | √ | × | √ |

| Du et al. [12] | SCM | Dual | √ | × | √ | × | × |

| Chauhan et al. [13] | SSCM | Dual | √ | × | × | × | √ |

| Gautam et al. [14] | SCM | Offline | × | × | × | × | √ |

| Battaglini [15] | SCM | Single | × | √ | × | × | √ |

| Song et al. [16] | SCN | Single | × | √ | × | × | × |

| Mahapatra et al. [17] | SCM | Dual | × | × | √ | √ | √ |

| Liu et al. [18] | SCM | Single | × | √ | × | × | √ |

| Chauhan and Majumder [19] | SCM | Fuzzy | √ | × | × | √ | √ |

| This paper | SCN | Dual | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Decision | Variables |

|---|---|

| Level of green innovation (manufacturer) | |

| , | Manufacturer’s online and offline cybersecurity, respectively (manufacturer) |

| , | Manufacturer’s customized product design through online and offline, respectively (manufacturer) |

| Online selling price (manufacturer) ($/unit) | |

| Level of advertisement (retailer) | |

| Retailer cybersecurity (retailer) | |

| Retailer’s customized product design (retailer) | |

| Offline selling price (retailer) ($/unit) | |

| Dependent | Variable |

| Wholesale price, which is dependent on the online selling price of manufacturer ($/unit) | |

| Parameters | Description |

| Retailer | |

| a | Base market demand (units) |

| Customer’s choice of preferred channel | |

| Scaling parameter representing demand based on the selling price in the same and opponent channels | |

| Scaling parameter representing demand for advertisement and greenness | |

| Cost coefficient of advertisement ($) | |

| Retailer’s variable transportation cost ($/item) | |

| Retailer’s fixed transportation cost ($) | |

| Investment scaling parameter for the retailer’s customized product design ($) | |

| Investment scaling parameter for retailer cybersecurity ($) | |

| Shape parameter for retailer customized product design | |

| Shape parameter for retailer cybersecurity | |

| Scaling parameter in demand for retailer customized product design | |

| Scaling parameter in demand for retailer cybersecurity | |

| Manufacturer | |

| h | Fixed discount on price |

| Cost coefficient of green investment ($) | |

| Scaling parameter representing demand for cybersecurity of the manufacturer through online and offline channels | |

| Scaling parameter representing manufacturer customized product design in online and offline channels | |

| Shape parameter for manufacturer cybersecurity through online and channels | |

| Shape parameters for manufacturer product design through online and online channels | |

| Scaling parameter related to cybersecurity investment of manufacturer through online and offline channels, respectively ($) | |

| Investment scaling parameter of the manufacturer for customized product design through online and offline channels, respectively ($) | |

| Manufacturer’s variable transportation cost ($/item) | |

| Manufacturer’s fixed transportation cost ($) | |

| Descriptions | Decision Variables | CP Method | VN Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Offline selling price | ($/unit) | 126.07 ($/unit) | 117.81 ($/unit) |

| Online selling price | ($/unit) | 111.85 ($/unit) | 105.9 ($/unit) |

| Green innovation | 23.01 | 18.65 | |

| Advertisement | 9.06 | 2.32 | |

| Cybersecurity online | 4.12 | 3.93 | |

| Cybersecurity offline | 4.8 | 3.6 | |

| Cybersecurity of retailer | 6.23 | 2.35 | |

| Customized product design online | 6.53 | 6.26 | |

| Customized product design offline | 5.01 | 3.67 | |

| Customized product design for retailer | 6.56 | 2.3 | |

| Total profit | |||

| Retailer’s profit | ($) | − | 11,565.56 ($) |

| Manufacturer’s profit | ($) | − | 40,372.77 ($) |

| SCN’s profit | ($) | 53,165.67 ($) | − |

| Descriptions | CP Method | VN Method | Discussions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profit | $53,165.67 (SCN) | $11,565.56 (retailer) and $40,372.77 (manufacturer) | In comparison, the total profit in the VN method is less than the profit in the CP method. Hence, the centralized scenario is the best. |

| Selling Price | The offline and online selling prices are $126.07/unit and $111.85/unit. | The offline and online selling prices are $117.81/unit and $105.9/unit. | Both offline and online prices in the CP method are greater than the prices in the VN method. This is because green innovation, advertisement, cybersecurity, and customized product engagement in the CP method are more than VN method. As a result, the maximum profit is obtained in the CP method. |

| Strategy | Retailer and manufacturer take decisions collaboratively. | Retailer and manufacture take decision independently. | Industry manager can choose any type of strategy based on the business policy. |

| Managerial Insights | CP has higher profit with high value of decisions. | VN has lower profit with lesser value of decisions than CP. | The difference between profits of CP and VN method is less. Thus, industry managers should prioritize the CP method to run a business with more profit. If any SCN player wants to continue independently, the manager can use the VN strategy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mandal, P.; Guchhait, R.; Dey, B.K.; Sarkar, M.; Pareek, S.; Ganguly, A. Customized Product Design and Cybersecurity Under a Nash Game-Enabled Dual-Channel Supply Chain Network. Mathematics 2026, 14, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010192

Mandal P, Guchhait R, Dey BK, Sarkar M, Pareek S, Ganguly A. Customized Product Design and Cybersecurity Under a Nash Game-Enabled Dual-Channel Supply Chain Network. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010192

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandal, Parthasarathi, Rekha Guchhait, Bikash Koli Dey, Mitali Sarkar, Sarla Pareek, and Anirban Ganguly. 2026. "Customized Product Design and Cybersecurity Under a Nash Game-Enabled Dual-Channel Supply Chain Network" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010192

APA StyleMandal, P., Guchhait, R., Dey, B. K., Sarkar, M., Pareek, S., & Ganguly, A. (2026). Customized Product Design and Cybersecurity Under a Nash Game-Enabled Dual-Channel Supply Chain Network. Mathematics, 14(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010192