Dynamic Topology-Aware Linear Attention Network for Efficient Traveling Salesman Problem Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

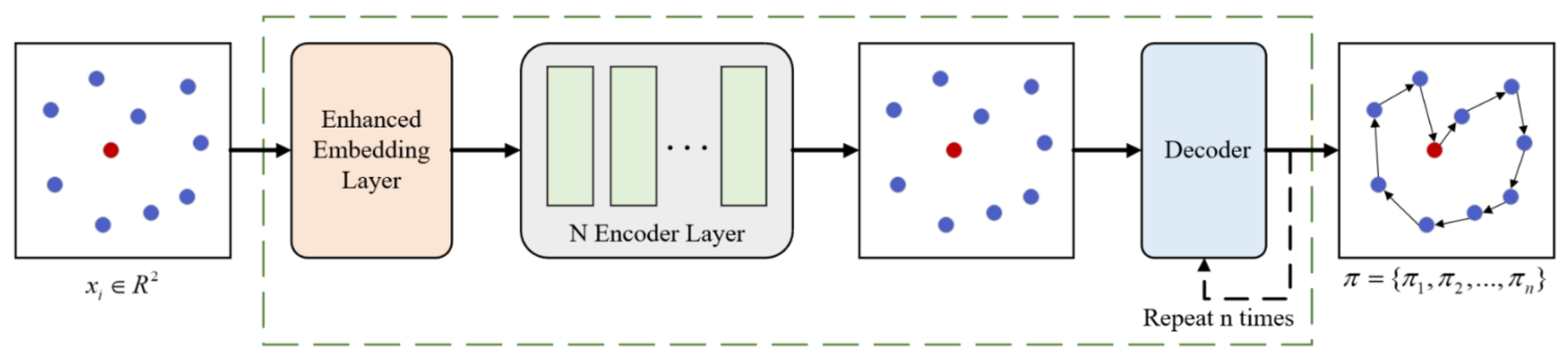

- A dynamic topology-aware encoder for TSP is introduced, which uniquely integrates a Channel-aware Topological Refinement Graph Convolution (CTRGC) with a Global Attention Mechanism (GAM). The CTRGC module captures dynamic local geometric structures between nodes via k-NN-based graph attention, addressing the standard Transformer’s weakness in local structure modeling. Concurrently, the GAM module adaptively recalibrates feature dimensions through channel-wise weighting, enhancing the representation of multi-scale path dependencies.

- To address TSP-specific challenges, a lightweight decoder featuring temporal locality-aware attention is proposed. By focusing attention only on the most recently visited nodes rather than the entire history, this design reduces the self-attention complexity from quadratic to linear levels. It effectively alleviates memory and computational bottlenecks for large-scale TSP instances while maintaining solution quality comparable to theoretical optima.

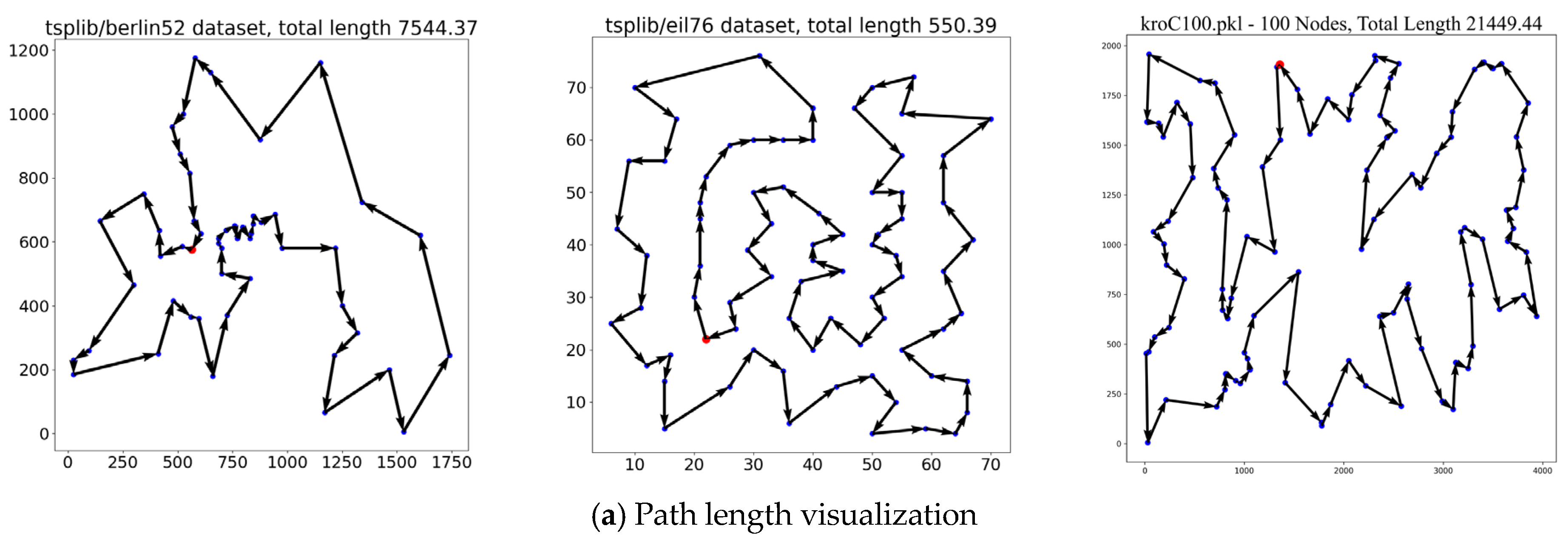

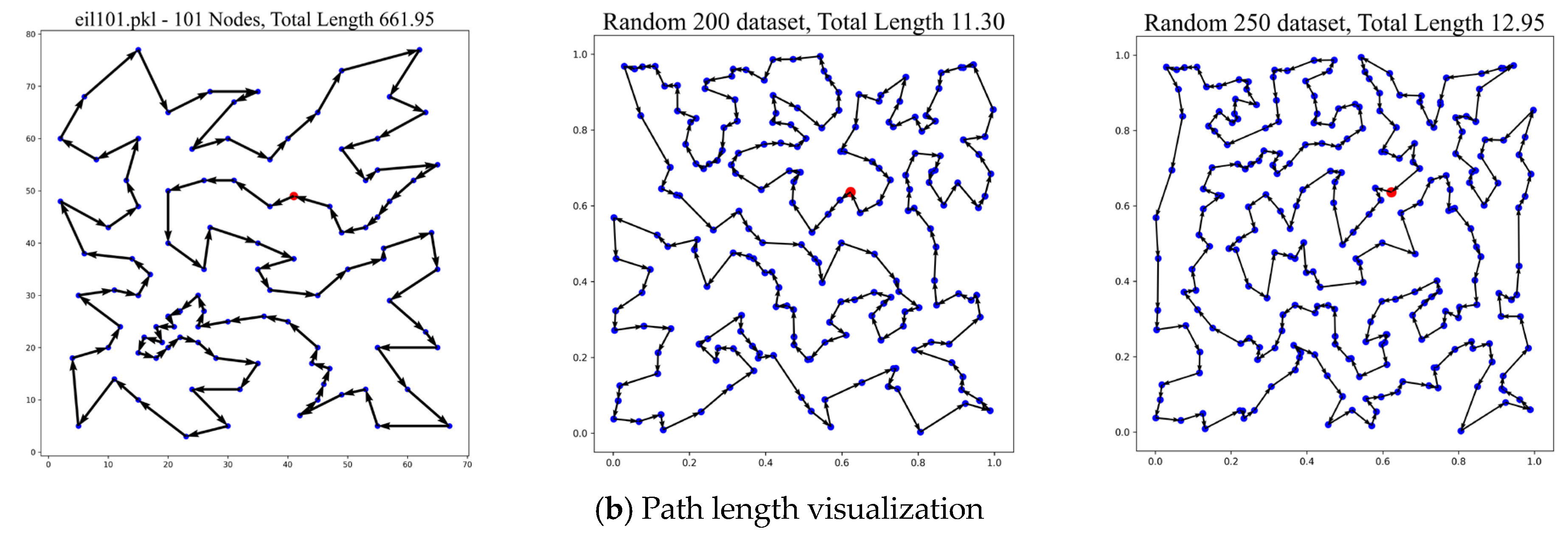

- During experiments, the trained model was evaluated not only on random instances but also on public real-world datasets with different distributions and on larger problem sizes. The results demonstrate that the proposed model can effectively solve real-world instances without retraining, confirming its strong generalization capability.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Algorithm

2.2. End-to-End DRL Algorithms

3. Method

3.1. Problem Definition

3.2. Network Architecture

3.2.1. Encoder

3.2.2. Decoder

3.3. Training Method

| Algorithm 1 Reinforce Learning Algorithm for TSP |

| Input: Instance , number of epochs , batch size Output: Trained parameters 1: init 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: 7: 8: 9: 10: End for |

4. Experimentation

4.1. Experimental Data

4.2. Hyperparameter Settings

4.3. Evaluation Indicators

4.4. Results and Analysis

4.4.1. Random Dataset Experiments

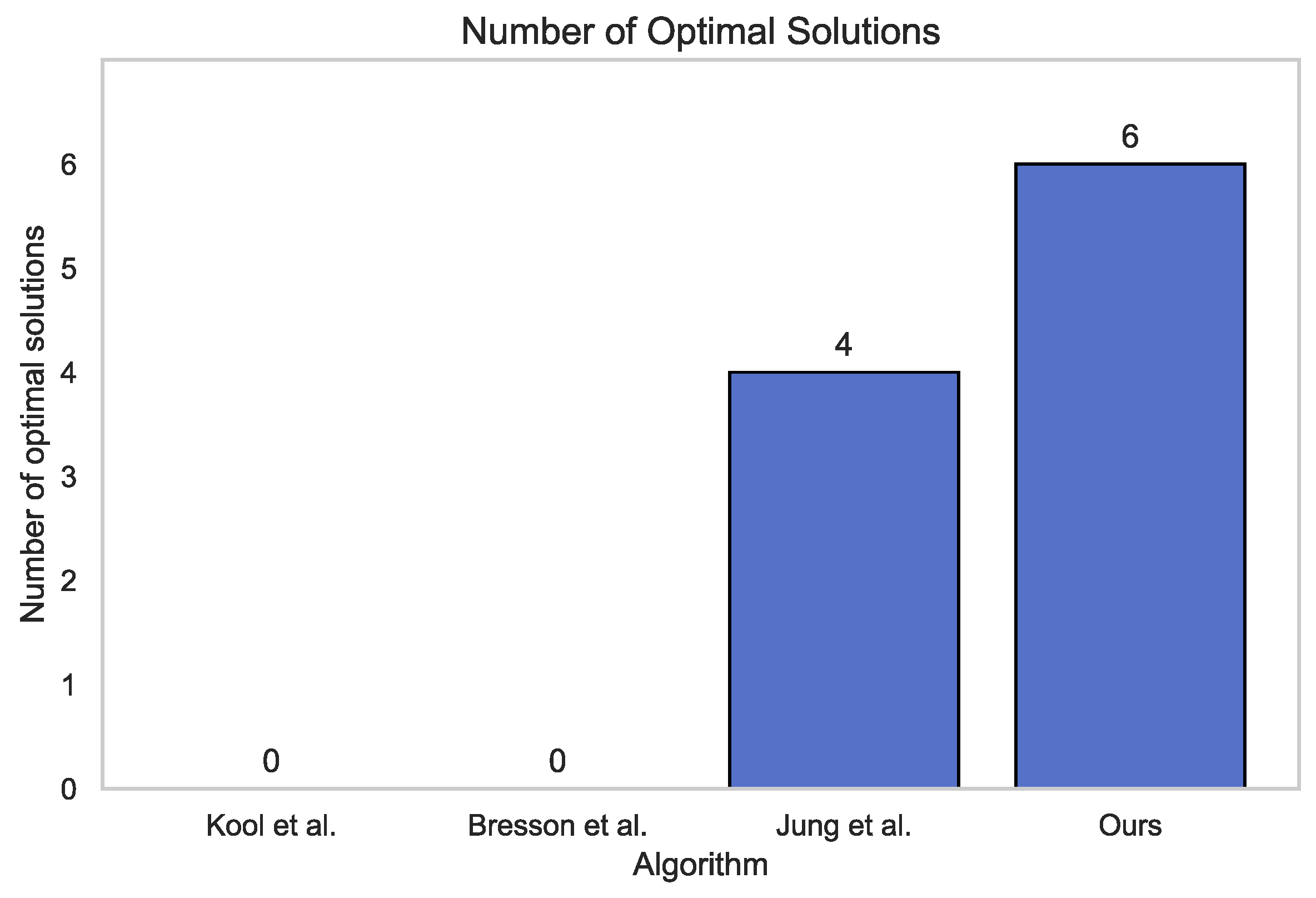

4.4.2. TSPLIB Dataset Experiments

4.5. Ablation Experiment

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halim, A.H.; Ismail, I. Combinatorial Optimization: Comparison of Heuristic Algorithms in Travelling Salesman Problem. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2017, 26, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.-W.; Zhao, X.; Ji, K. Region Division in Logistics Distribution with a Two-Stage Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 212876–212887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwubolu, G.C.; Clerc, M. Optimal path for automated drilling operations by a new heuristic approach using particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2004, 42, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, A.; Batta, R.; Karwan, M. The balancing traveling salesman problem: Application to warehouse order picking. Top 2021, 29, 442–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.; Roy, K. Neuro-Ising: Accelerating Large-Scale Traveling Salesman Problems via Graph Neural Network Guided Localized Ising Solvers. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2022, 41, 5408–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melab, N.; Mezmaz, M. Multi and many-core computing for parallel metaheuristics. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2017, 29, e4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, D.L.; Bixby, R.E.; Chvátal, V.; Cook, W.J. The Traveling Salesman Problem: A Computational Study. In The Traveling Salesman Problem; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Wang, Q. Learning for multiple purposes: A Q-learning enhanced hybrid metaheuristic for parallel drone scheduling traveling salesman problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsgaun, K. An Extension of the Lin-Kernighan-Helsgaun TSP Solver for Constrained Traveling Salesman and Vehicle Routing Problems. Rosk. Rosk. Univ. 2017, 12, 966–980. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Liang, X.; Zhao, D.; Huang, J.; Xu, X.; Dai, B.; Miao, Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 5064–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, C. A Travel Salesman Problem Solving Algorithm Based on Feature Enhanced Attention Model. J. Comput. 2024, 35, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Feng, X.-F.; Li, F.; Xian, Q.-L.; Jia, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Du, Z.-D. Deep reinforcement learning combined with transformer to solve the traveling salesman problem. J. Supercomput. 2024, 81, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.M.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 12 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bresson, X.; Laurent, T. The Transformer Network for the Traveling Salesman Problem. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Taji, K.; Fukushima, M. Probabilistic analysis of 2-opt for travelling salesman problems. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1998, 29, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofides, N. Worst-Case Analysis of a New Heuristic for the Travelling Salesman Problem. Oper. Res. Forum 2022, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G.; Wright, J.W. Scheduling of Vehicles from a Central Depot to a Number of Delivery Points. Oper. Res. 1964, 12, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmore, M.; Nemhauser, G.L. The Traveling Salesman Problem: A Survey. Oper. Res. 1968, 16, 538–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkrantz, D.J.; Stearns, R.E.; Lewis, P.M., II. An Analysis of Several Heuristics for the Traveling Salesman Problem. SIAM J. Comput. 1977, 6, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Ding, S.; Huang, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, R.; Xia, B.; Ding, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Yu, C.; et al. A survey on deep learning-based algorithms for the traveling salesman problem. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 19, 196322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyals, O.; Fortunato, M.; Jaitly, N. Pointer Networks. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.V.; Norouzi, M.; Bengio, S. Neural Combinatorial Optimization with Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Oroojlooy, A.; Snyder, L.; Takác, M. Reinforcement Learning for Solving the Vehicle Routing Problem. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 12 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deudon, M.; Cournut, P.; Lacoste, A.; Adulyasak, Y.; Rousseau, L.-M. Learning Heuristics for the TSP by Policy Gradient. In Integration of Constraint Programming, Artificial Intelligence, and Operations Research; Van Hoeve, W.-J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kool, W.; Hoof, H.V.; Welling, M. Attention, Learn to Solve Routing Problems! In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.-D.; Choo, J.; Kim, B.; Yoon, I.; Gwon, Y.; Min, S. POMO: Policy Optimization with Multiple Optima for Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020), Virtual, 30 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Jin, Y.; Ding, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhao, L.; Song, L.; Bian, J. H-TSP: Hierarchically Solving the Large-Scale Travelling Salesman Problem. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2023), Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lischka, A.; Wu, J.; Basso, R.; Chehreghani, M.H.; Kulcsár, B. Less is More—On the Importance of Sparsification for Transformers and Graph Neural Networks for TSP. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.17159. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Lin, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z. Neural Combinatorial Optimization with Heavy Decoder: Toward Large Scale Generalization. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2023, Main Conference Track, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, E.B.; Dai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dilkina, B.; Song, L. Learning Combinatorial Optimization Algorithms over Graphs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.01665. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Ge, S.; He, D.; Thaker, D.; Drori, I. Combinatorial Optimization by Graph Pointer Networks and Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.04936. [Google Scholar]

- Drori, I.; Kharkar, A.; Sickinger, W.R.; Kates, B.; Ma, Q.; Ge, S.; Dolev, E.; Dietrich, B.; Williamson, D.P.; Udell, M. Learning to Solve Combinatorial Optimization Problems on Real-World Graphs in Linear Time. In Proceedings of the 2020 19th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Miami, FL, USA, 14–17 December 2020; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, K.; Guo, P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, W. Solve routing problems with a residual edge-graph attention neural network. Neurocomputing 2022, 508, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Wang, Y.; Weng, P.; Han, S. Generalization in Deep RL for TSP Problems via Equivariance and Local Search. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.03595. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Li, B.; Deng, Y.; Hu, W. Channel-wise Topology Refinement Graph Convolution for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.03595. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Hoffmann, N. Global Attention Mechanism: Retain Information to Enhance Channel-Spatial Interactions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05561. [Google Scholar]

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The Long-Document Transformer. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinelt, G. TSPLIB—A Traveling Salesman Problem Library. ORSA J. Comput. 1991, 3, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fang, M.; Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Du, Y.; Zhang, C. Reinforcement Learning with Multiple Relational Attention for Solving Vehicle Routing Problems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 11107–11120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, C.K.; Cappart, Q.; Rousseau, L.-M.; Laurent, T. Learning TSP Requires Rethinking Generalization. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming (CP 2021), Montpellier, France, 25–29 October 2021; Volume 2021, pp. 33:1–33:21. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. A lightweight CNN-transformer model for learning traveling salesman problems. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 7982–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Prokhorchuk, A.; Dauwels, J. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Traveling Salesman Problem with Time Windows and Rejections. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Type | TSP20 | TSP50 | TSP100 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Len | Gap | Time | Len | Gap | Time | Len | Gap | Time | ||

| Concorde | Solver | 3.83 | 0.00% | 18 s | 5.69 | 0.00% | 2 min | 7.76 | 0.00% | 3 min |

| NI | H,G | 4.33 | 12.91% | 1 s | 6.78 | 19.03% | 2 s | 9.46 | 21.82% | 6 s |

| RI | H,G | 4.00 | 4.36% | 0 s | 6.13 | 7.65% | 1 s | 8.52 | 9.69% | 3 s |

| FI | H,G | 3.93 | 2.36% | 1 s | 6.01 | 5.53% | 2 s | 8.35 | 7.59% | 7 s |

| NN | H,G | 4.50 | 17.23% | 0 s | 7.00 | 22.94% | 0 s | 9.68 | 24.73% | 0 s |

| Vinyals [21] | SL,G | 3.88 | 1.15% | - | 7.66 | 34.48% | - | - | - | - |

| Bello [22] | RL,G | 3.89 | 1.42% | - | 5.95 | 4.46% | - | 8.30 | 6.90% | - |

| Dai [30] | RL,G | 3.89 | 1.42% | - | 5.99 | 5.16% | - | 8.31 | 7.03% | - |

| Deudon [24] | RL,G | 3.86 | 0.66% | 2 min | 5.92 | 3.98% | 5 min | 8.42 | 8.41% | 8 min |

| Deudon [24] | RL,2-OPT | 3.85 | 0.42% | 4 min | 5.85 | 2.77% | 26 min | 8.17 | 5.21% | 3 h |

| Kool [25] | RL,G | 3.85 | 0.34% | 0 s | 5.80 | 1.76% | 2 s | 8.12 | 4.53% | 6 s |

| Xu [40] | RL,G | 3.84 | 0.26% | 0.37 s | 5.76 | 1.23% | 0.91 s | 8.05 | 3.74% | 2 s |

| Joshi [41] | SL,G | 3.86 | 0.60% | 6 s | 5.87 | 3.10% | 55 s | 8.41 | 8.38% | 6 min |

| Bresson [14] | RL,G | 3.89 | 1.57% | 0 s | 5.75 | 1.05% | 14 s | 8.01 | 3.22% | 19 s |

| Jung [42] | RL,G | 3.84 | 0.25% | 0 s | 5.75 | 0.98% | 6 s | 8.00 | 3.00% | 12 s |

| Ours | RL,G | 3.84 | 0.36% | 2 s | 5.74 | 0.96% | 1 s | 7.96 | 2.64% | 4 s |

| Bello [22] | RL,S | - | - | - | 5.75 | 0.95% | - | 8.00 | 3.03% | - |

| Zhang [43] | RL,S | 3.84 | 0.11% | 5 min | 5.77 | 1.28% | 17 min | 8.75 | 12.70% | 56 min |

| Kool [25] | RL,B | 3.84 | 0.08% | 5 min | 5.73 | 0.52% | 24 min | 7.94 | 2.26% | 1 h |

| Bresson [14] | RL,B | 3.85 | 0.34% | 14 min | 5.75 | 0.97% | 44.8 min | 7.86 | 1.26% | 1.5 h |

| Jung [42] | RL,B | 3.83 | 0.00% | 1.4 min | 5.72 | 0.46% | 26.2 min | 7.86 | 1.22% | 1.83 h |

| Ours | RL,B | 3.83 | 0.00% | 2 min | 5.72 | 0.67% | 11 min | 7.80 | 0.55% | 50 min |

| Problem | Avg Cost | Avg Serial Duration | Avg Parallel Duration | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSP20 | 3.84 ± 0.006 | 0.214 ± 0.009 | 0.0002 | 2 s |

| TSP50 | 5.74 ± 0.005 | 0.172 ± 0.003 | 0.0001 | 1 s |

| TSP100 | 7.96 ± 0.005 | 0.360 ± 0.003 | 0.0004 | 4 s |

| Problem | Concorde | Kool et al. [25] | Bresson et al. [14] | Jung et al. [42] | Ours | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Len | Gap | Len | Gap | Len | Gap | Len | Gap | ||

| eil51 | 426 | 439 | 3.05% | 438 | 2.82% | 429 | 0.70% | 433 | 1.64% |

| berlin52 | 7542 | 8017 | 6.30% | 7637 | 1.26% | 7610 | 0.90% | 7544 | 0.03% |

| st70 | 675 | 698 | 3.41% | 710 | 5.19% | 676 | 0.15% | 689 | 2.07% |

| eil76 | 538 | 560 | 4.09% | 565 | 5.02% | 564 | 4.83% | 550 | 2.23% |

| kroA100 | 21,282 | 23,078 | 8.44% | 21,747 | 2.18% | 21,620 | 1.59% | 21,824 | 2.55% |

| kroC100 | 20,749 | 21,565 | 3.93% | 21,788 | 5.01% | 21,523 | 3.73% | 21,449 | 3.37% |

| rd100 | 7910 | 8441 | 6.71% | 8078 | 2.12% | 8044 | 1.69% | 8348 | 5.54% |

| eil101 | 629 | 665 | 5.72% | 681 | 8.27% | 668 | 6.20% | 662 | 5.25% |

| ch130 | 6110 | 6549 | 7.18% | 6569 | 7.51% | 6552 | 7.23% | 6208 | 1.60% |

| ch150 | 6528 | 7242 | 10.94% | 7390 | 13.20% | 7050 | 8.00% | 6682 | 2.36% |

| Problem | Kool [25] | Bresson [14] | Jung [42] | Ours |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eil51 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| berlin52 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| st70 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| eil76 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| kroA100 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| kroC100 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| rd100 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| eil101 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| ch130 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| ch150 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Model | Len | Gap |

|---|---|---|

| Variant 1 | 7.817 | 0.73% |

| Variant 2 | 7.819 | 0.76% |

| Variant 3 | 7.821 | 0.78% |

| Ours | 7.803 | 0.55% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, S.; Duan, Q. Dynamic Topology-Aware Linear Attention Network for Efficient Traveling Salesman Problem Optimization. Mathematics 2026, 14, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010166

Zhao S, Duan Q. Dynamic Topology-Aware Linear Attention Network for Efficient Traveling Salesman Problem Optimization. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010166

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Shilong, and Qianqian Duan. 2026. "Dynamic Topology-Aware Linear Attention Network for Efficient Traveling Salesman Problem Optimization" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010166

APA StyleZhao, S., & Duan, Q. (2026). Dynamic Topology-Aware Linear Attention Network for Efficient Traveling Salesman Problem Optimization. Mathematics, 14(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010166