Artificial Intelligence and the Emergence of New Quality Productive Forces: A Machine Learning Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Direct Impact Mechanism of Artificial Intelligence on Corporate New Quality Productive Forces

2.1.1. AI-Driven Enhancement of Technological Innovation Efficiency Through Factor Reconfiguration

2.1.2. Optimization of Factor Allocation Efficiency Through Asymmetric Information Mitigation by AI

Mitigation of Information Asymmetry

Reduction in Transaction Costs

2.1.3. The Enhancement of Industrial Synergy Efficiency Through Digitally Intelligent Agglomeration

Virtual Agglomeration Mechanisms

Emergence of Novel Industrial Archetypes

2.2. Moderating Mechanisms: The Reinforcing Role of Boundary Conditions

2.2.1. Directors’ Technology Background: Strengthening the Implementation of AI-Driven Innovation

Strategic Technology Selection and Deployment

Knowledge Integration and Organizational Learning

Human–Machine System Optimization

2.2.2. The Amplification of AI-Driven Factor Allocation Through Digital Industrial Agglomeration

Data Resource Concentration and Algorithmic Refinement

Inter-Organizational Innovation Networks

Technological Diffusion and Productivity Conversion

2.2.3. Financial Agglomeration: Mitigating Resource Constraints in AI Development and Deployment

Reducing Financing Constraints Through Diversified Capital Access

Accelerating Commercialization Through Specialized Financial Ecosystems

Enhancing Investment Efficiency Through Proximity-Based Information Advantages

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Specification

3.2. Data

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Explanatory Variable: Firms’ Level of Artificial Intelligence Development (AItech)

3.3.2. New Quality Productive Force (NQPF)

3.3.3. Control Variables

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

4.2. Endogeneity Tests

4.2.1. Instrumental Variables Test

4.2.2. Propensity Score Matching

4.2.3. Kinky Least Squares Estimation

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Replacement of Core Variables

4.3.2. Change in Sample Interval

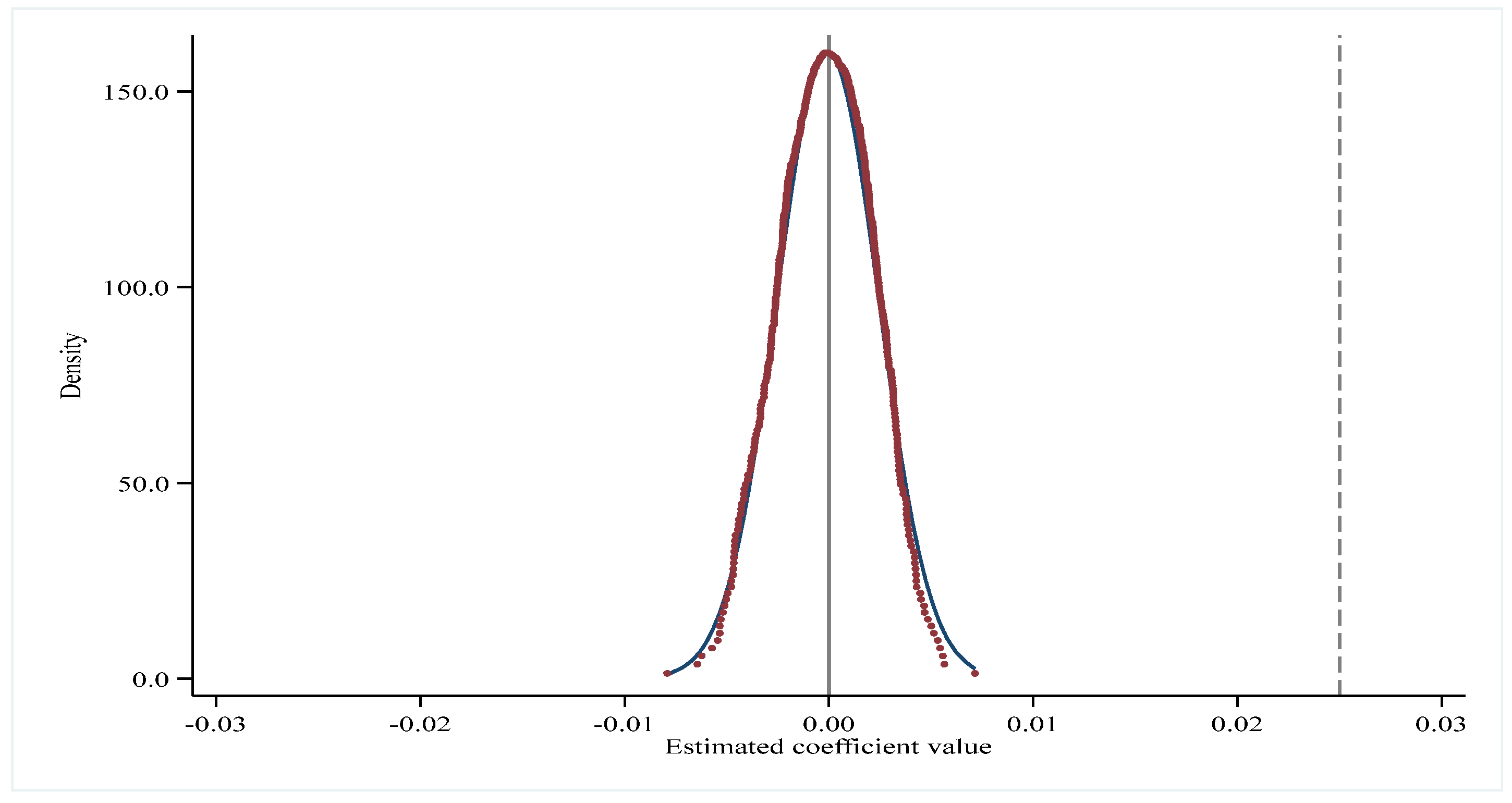

4.3.3. Placebo Test

4.4. Moderating Mechanism Tests

4.4.1. Digital Industry Clustering

4.4.2. Directors’ Technological Background

4.4.3. Financial Cluster

4.5. Heterogeneity Tests

4.5.1. Enterprise Technology Background

4.5.2. Nature of Property Rights

4.5.3. Policy Support

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| NQPF | The natural logarithm of the word frequency representing new quality productive forces within the annual reports of listed companies is utilized |

| AItech | The natural logarithm of the number of invention-based AI applications filed by listed companies plus one |

| Tobinq | The ratio of the market value of a firm’s stock to the replacement cost of the asset represented by the stock |

| Size | The natural log of the number of employees |

| Roa | The ratio of company’s net profit to total assets |

| Levrage | Corporate liabilities as a percentage of total assets |

| BoardSize | The natural log of the number of directors on the board |

| Growth | The ratio of increase in operating income for the current year to total operating income for the previous year |

| Age | The current year minus the year of listing plus one is taken as the natural logarithm |

| Dual | Chairman and CEO are the same person |

| Top1 | The number of shares held by the largest shareholder as a percentage of total shares |

| Lnallpats | Total number of patent applications filed by firms plus one taken as a natural logarithm |

| VarName | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AItech | 28,293 | 0.44 | 1.86 | 0.000 | 14.000 |

| NQPF | 28,293 | 2.40 | 1.12 | 0.000 | 4.796 |

| Tobinq | 28,293 | 1.99 | 1.21 | 0.848 | 7.826 |

| ROA | 28,293 | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.164 | 0.210 |

| Size | 28,293 | 22.28 | 1.28 | 20.029 | 26.248 |

| Age | 28,293 | 2.91 | 0.33 | 1.792 | 3.526 |

| Leverage | 28,293 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.060 | 0.880 |

| Growth | 28,293 | 0.17 | 0.38 | −0.522 | 2.311 |

| BoardSize | 28,293 | 2.13 | 0.20 | 1.609 | 2.708 |

| Dual | 28,293 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| TOP1 | 28,293 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.094 | 0.748 |

| Lnallpats | 28,293 | 2.81 | 1.77 | 0.000 | 7.056 |

References

- Liu, W. Scientific understanding and practical development of new qualitative productive forces. Econ. Res. J. 2024, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, W.; Zhang, K.; Guo, L.; Feng, X. How can artificial intelligence improve enterprise production efficiency? From the perspective of the adjustment of labor skill structure. Manag. World 2024, 101–116+133+117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D. Computing power: A new qualitative productivity in the era of digital economy. Financ. Trade Res. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. AI large model empowers the accelerated development of new qualitative productive forces: Internal mechanism, practical obstacles and practical approaches. Reform Strategy 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.H.; Rust, R.T. A strategic framework for artificial intelligence in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. The simple macroeconomics of AI. Econ. Policy 2025, 40, 13–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.W.; Xie, D.; Zhang, L. Knowledge accumulation, privacy, and growth in a data economy. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 6480–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammer, C.; Fernández, G.P.; Czarnitzki, D. Artificial intelligence and industrial innovation: Evidence from German firm-level data. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, T.; Fedyk, A.; He, A.; Hodson, J. Artificial intelligence, firm growth, and product innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 151, 103745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Ren, X.; Shi, Y. AI adoption rate and corporate green innovation efficiency: Evidence from Chinese energy companies. Energy Econ. 2024, 132, 107499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridis, C.A.; Mishra, S. Artificial intelligence as a service, economic growth, and well-being. J. Serv. Res. 2022, 25, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, S.; Zhang, W. Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence. Science 2023, 381, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damioli, G.; Van Roy, V.; Vertesy, D. The impact of artificial intelligence on labor productivity. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2021, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Z. Synergistic Industrial Agglomeration, New quality productive forces and high-quality development of the manufacturing industry. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 94, 103373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y. A review on the economics of artificial intelligence. J. Econ. Surv. 2021, 35, 1045–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeihagh, A. Governance of artificial intelligence. Policy Soc. 2021, 40, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Intelligent productivity: A new quality productive forces. J. Contemp. Econ. Res. 2024, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.; Liu, Z. Artificial intelligence technology innovation and firm productivity: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.L.; Sun, T.T.; Xu, R.Y. The impact of artificial intelligence on total factor productivity: Empirical evidence from China’s manufacturing enterprises. Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 1113–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parteka, A.; Kordalska, A. Artificial intelligence and productivity: Global evidence from AI patent and bibliometric data. Technovation 2023, 125, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangqin, L.I.; Mengjiao, L.I. Provincial-level new quality productive forces in China: Evaluation, spatial pattern and evolution characteristics. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.H. How artificial intelligence technology affects productivity and employment: Firm-level evidence from Taiwan. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Yue, S.; Guo, C.; Gao, P. Unleashing global potential: The impact of digital technology innovation on corporate international diversification. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Lai, H.; Zhang, L.; Guo, L.; Lai, X. Does public data openness accelerate new quality productive forces? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montobbio, F.; Staccioli, J.; Virgillito, M.E.; Vivarelli, M. Robots and the origin of their labor-saving impact. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Luo, X.; Fang, Z.; Liao, C. When and how artificial intelligence augments employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2024, 67, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Wang, H.; Peng, Q.; Liu, S. Saving face: Leveraging artificial intelligence-based negative feedback to enhance employee job performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 63, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. Behavioral macroeconomics and macroeconomic behavior. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Xu, B.; Razzaq, A. Can application of artificial intelligence in enterprises promote the corporate governance? Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 944467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, M.; Anand, A.; Baird, A. Manager appraisal of artificial intelligence investments. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2024, 41, 682–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Gao, Y.; Sun, X. How does artificial intelligence affect green economic growth?—Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, M.; Obschonka, M.; Nambisan, S. Pursuing impactful entrepreneurship research using artificial intelligence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2022, 46, 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cui, H.; Wu, F. Does Financial Agglomeration Promote the Digital Transformation of Enterprises: Empirical Evidence Based on Big Data Analysis of Enterprise Annual Report Text. South. Econ. 2022, 60–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Yang, S.; Maqsood, U.S.; Zahid, R.A. Tapping into the green potential: The power of artificial intelligence adoption in corporate green innovation drive. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4375–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Textual analysis of corporate disclosures: A survey of the literature. J. Account. Lit. 2010, 29, 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Brochet, F.; Loumioti, M.; Serafeim, G. Speaking of the short-term: Disclosure horizon and managerial myopia. Rev. Account. Stud. 2015, 20, 1122–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Ducharme, R.; Vincent, P.; Jauvin, C. A neural probabilistic language model. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Feng, H. AI-driven productivity gains: Artificial intelligence and firm productivity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Gu, R.; Wang, P.; Hu, Y. How Does New Quality Productive Forces Affect Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency in China? Consider the Threshold Effect of Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, H.; Chen, Z. Artificial intelligence and the new quality productive forces of enterprises: Digital intelligence empowerment paths and spatial spillover effects. Systems 2025, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, S. Internet development and manufacturing productivity improvement: Internal mechanism and Chinese experience. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 8, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kiviet, J.F. Testing the impossible: Identifying exclusion restrictions. J. Econom 2020, 218, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviet, J.F. Instrument-free inference under confined regressor endogeneity and mild regularity. Econom. Stat. 2023, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Njangang, H.; Padhan, H.; Simo, C.; Yan, C. Social media and energy justice: A global evidence. Energy Econ. 2023, 125, 106886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, B. Research on the firm spatial distribution and influencing factors of the service-oriented digital industry in yangtze river delta. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Li, L.; Han, Y.; Hao, Y.; Wu, H. The emerging driving force of inclusive green growth: Does digital economy agglomeration work? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1656–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, G. The impact of techno-executive power and non-techno-executive power on firm performance: An empirical test from China’s A-share listed high-tech enterprises. Account. Res. 2017, 73–79+97. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Ge, X. Financial agglomeration, government intervention, opening-up and regional economic development. Stat. Decis. 2022, 150–153. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | |

| AItech | 0.122 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.025 *** |

| (35.024) | (12.168) | (8.172) | |

| Size | −0.071 *** | 0.175 *** | |

| (−11.538) | (13.998) | ||

| Leverage | −0.463 *** | −0.477 *** | |

| (−12.768) | (−9.890) | ||

| Tobinq | −0.005 | −0.005 | |

| (−0.895) | (−0.982) | ||

| Growth | 0.109 *** | 0.011 | |

| (6.742) | (0.852) | ||

| BoardSize | −0.027 | 0.111 *** | |

| (−0.940) | (2.827) | ||

| Dual | 0.110 *** | 0.014 | |

| (8.905) | (1.016) | ||

| TOP1 | −0.005 *** | −0.000 | |

| (−13.221) | (−0.657) | ||

| Age | −0.374 *** | −0.825 *** | |

| (−20.060) | (−10.701) | ||

| Lnallpats | 0.210 *** | 0.048 *** | |

| (57.801) | (8.993) | ||

| ROA | −0.243 ** | 0.190 * | |

| (−2.173) | (1.838) | ||

| Control | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | No | No | Yes |

| Firm FE | No | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 2.346 *** | 4.862 *** | 0.747 ** |

| (350.794) | (36.066) | (2.137) | |

| N | 28,293 | 28,293 | 28,293 |

| adj. R2 | 0.042 | 0.376 | 0.725 |

| Variable | Instrumental Variables Test | PSM | KLS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | First | Second | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| AItech | NQPF | AItech | NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | |

| AItech | 0.148 *** (5.681) | 0.129 *** (4.021) | ||||

| IV1 | 0.068 * (1.831) | |||||

| IV2 | 0.043 *** (4.035) | |||||

| PSM-AItech | 0.161 *** (3.461) | |||||

| KLS-AItech | 0.094 *** | |||||

| (2.781) | ||||||

| K-P rk LM F | 24.494 *** | 26.751 *** 28.884 | - | - | ||

| K-P rk Wald F | 23.174 | - | - | |||

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 23,573 | 23,573 | 23,247 | 23,247 | 4381 | 28,293 |

| Variable | MD&A | Laborers | Labor Materials | Labor Objects | Change Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| AItech | 0.029 *** | ||||

| (7.662) | |||||

| AItech | 0.033 *** | ||||

| (6.232) | |||||

| AItech | 0.038 *** | ||||

| (6.571) | |||||

| AItech | 0.041 *** | ||||

| (6.422) | |||||

| AItech | 0.023 *** | ||||

| (3.391) | |||||

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 28,293 | 28,293 | 28,293 | 28,293 | 19,076 |

| adj. R2 | 0.725 | 0.712 | 0.714 | 0.701 | 0.732 |

| Variable | High-Tech | Non-High-Tech | State-Owned | Non-State-Owned | High Policy Support | Low Policy Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | NQPF | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| AItech | 0.002 *** | 0.001 | 0.004 ** | 0.001 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.001 |

| (3.383) | (0.823) | (2.336) | (2.968) | (3.438) | (0.951) | |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 1.087 ** | −0.857 | 1.387 ** | −0.326 | −1.838 * | 0.497 |

| (2.450) | (−1.436) | (2.175) | (−0.716) | (−1.842) | (0.970) | |

| N | 15,803 | 12,490 | 10,837 | 17,456 | 11,147 | 17,146 |

| adj. R2 | 0.714 | 0.686 | 0.712 | 0.721 | 0.790 | 0.702 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tan, L.; Lai, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhong, Y. Artificial Intelligence and the Emergence of New Quality Productive Forces: A Machine Learning Perspective. Mathematics 2026, 14, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010135

Tan L, Lai X, Zhao Y, Zhong Y. Artificial Intelligence and the Emergence of New Quality Productive Forces: A Machine Learning Perspective. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010135

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Lei, Xiaobing Lai, Yuxin Zhao, and Yuan Zhong. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence and the Emergence of New Quality Productive Forces: A Machine Learning Perspective" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010135

APA StyleTan, L., Lai, X., Zhao, Y., & Zhong, Y. (2026). Artificial Intelligence and the Emergence of New Quality Productive Forces: A Machine Learning Perspective. Mathematics, 14(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010135