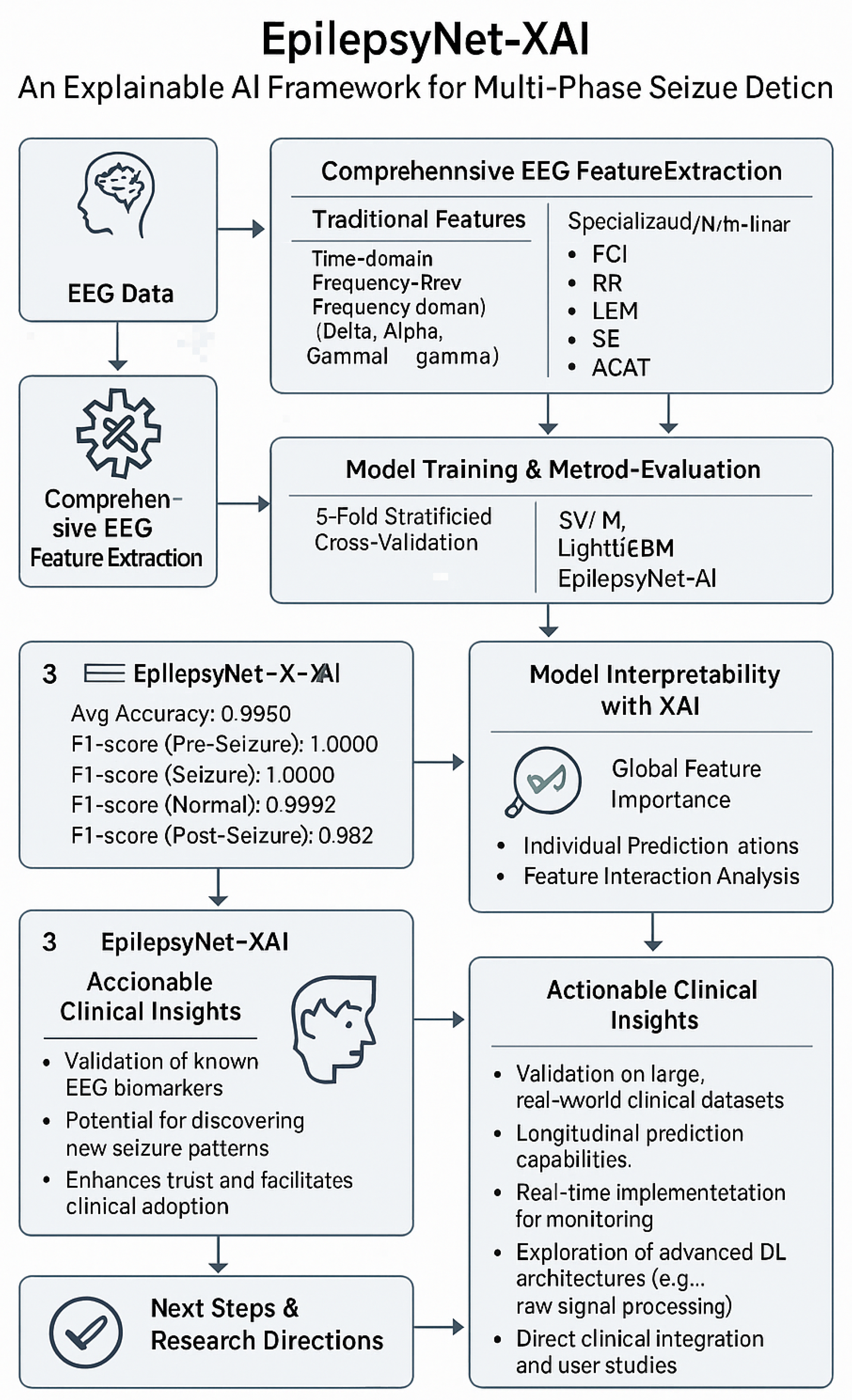

EpilepsyNet-XAI: Towards High-Performance and Explainable Multi-Phase Seizure Analysis from EEG Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives and Contributions

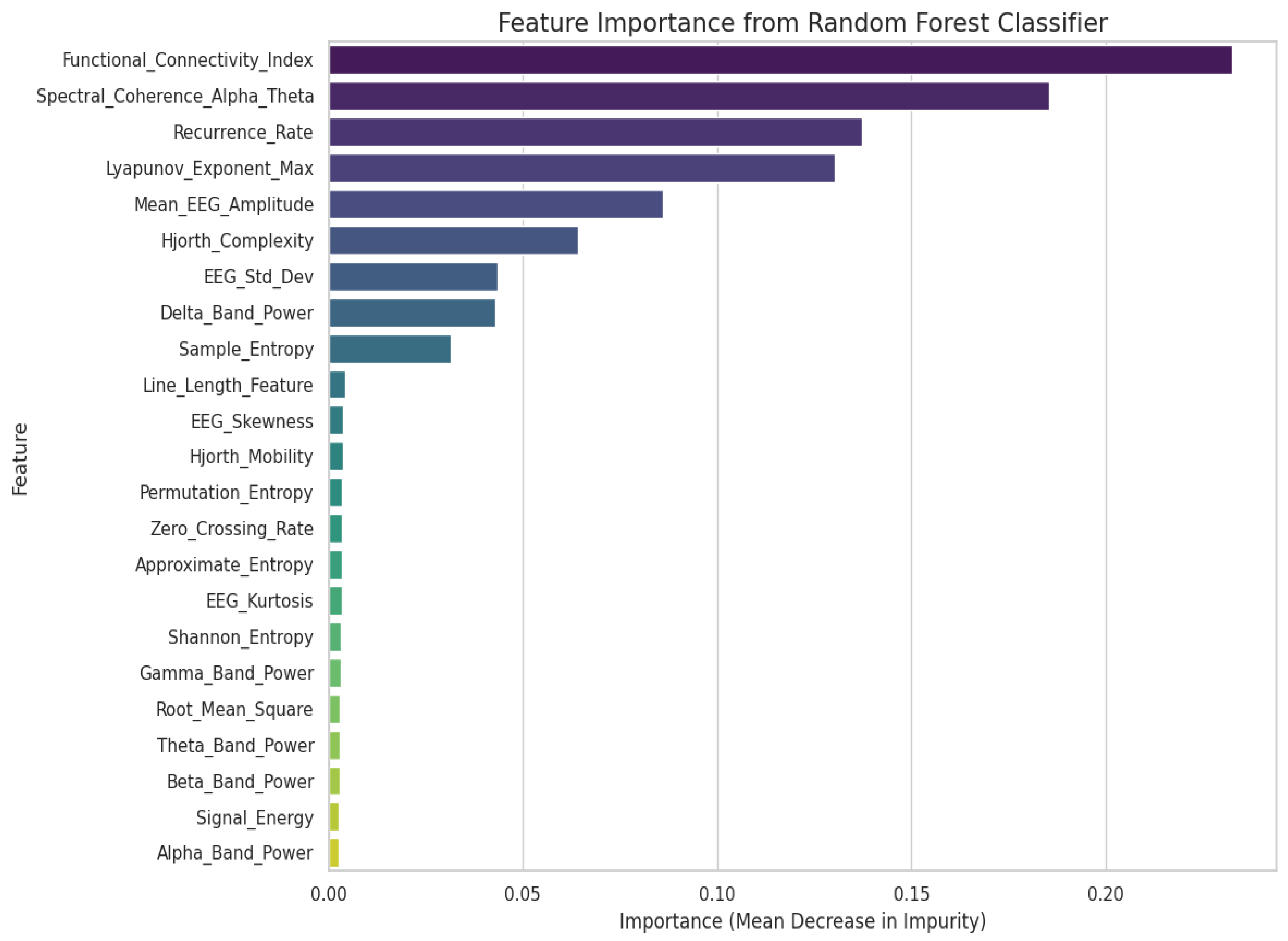

- Comprehensive feature-engineering pipeline: We extract and organize a structured set of time-domain, frequency-domain, and entropy-based features validated in neuroscientific and biomedical signal-processing literature. We explicitly evaluate the discriminative power of each feature group to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

- Systematic benchmarking of classical supervised models: Five widely adopted classifiers—Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, k-Nearest Neighbors, Gradient Boosting, and Multilayer Perceptron—are trained and compared under consistent preprocessing, segmentation, and class-balancing procedures.

- Model-agnostic interpretability using SHAP and LIME: We integrate SHAP and LIME explainability tools to quantify the contribution of individual EEG-derived features, providing clinically relevant interpretation that is often missing in prior public-dataset EEG studies.

- Ablation and robustness analyses: We introduce systematic evaluations, including feature-group ablation, class imbalance robustness, and noise perturbation analysis, thereby strengthening the empirical depth and distinguishing the work from prior studies.

- Reproducible workflow: The proposed pipeline is modular and easy to reproduce, enabling future extensions with alternative feature sets or hybrid models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

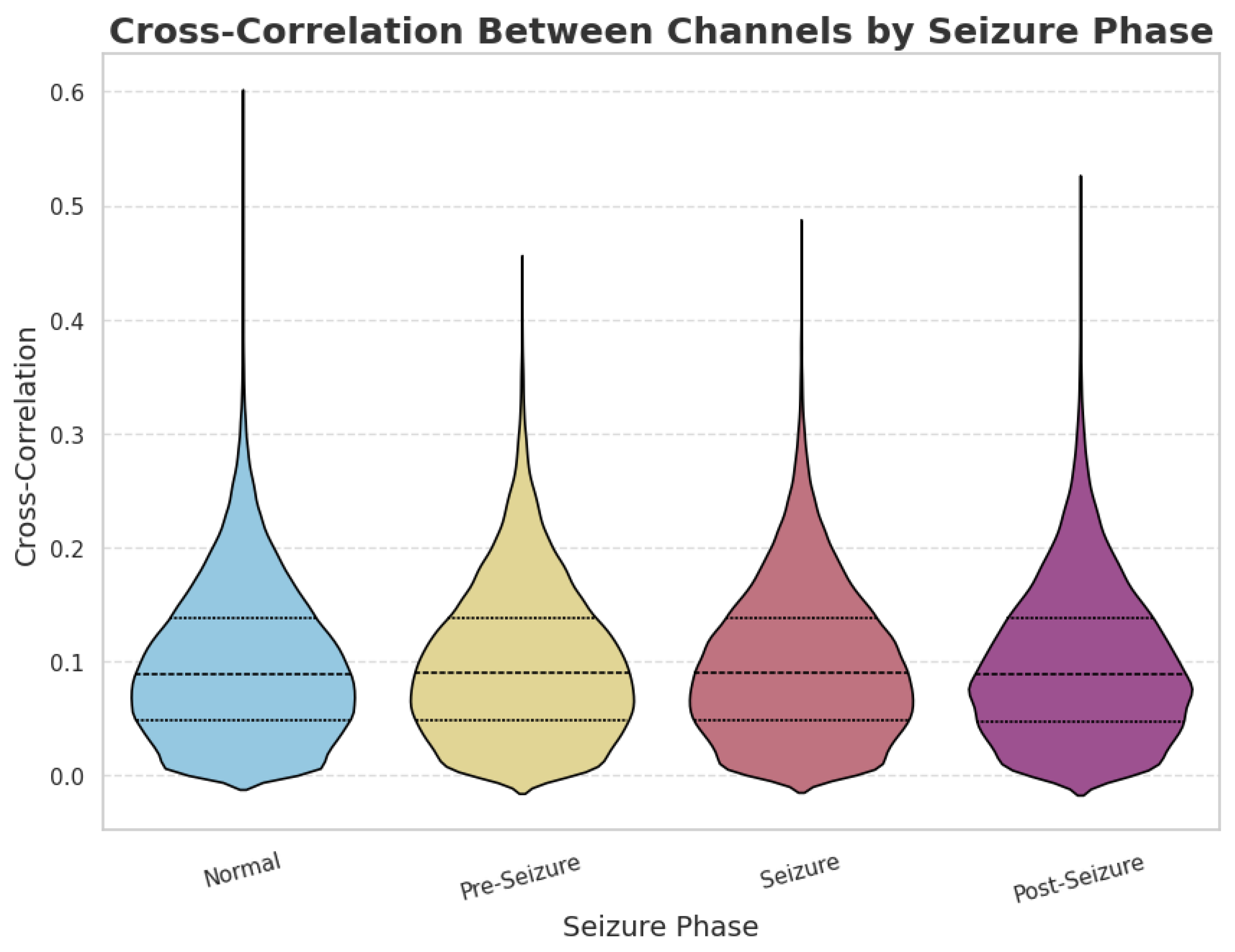

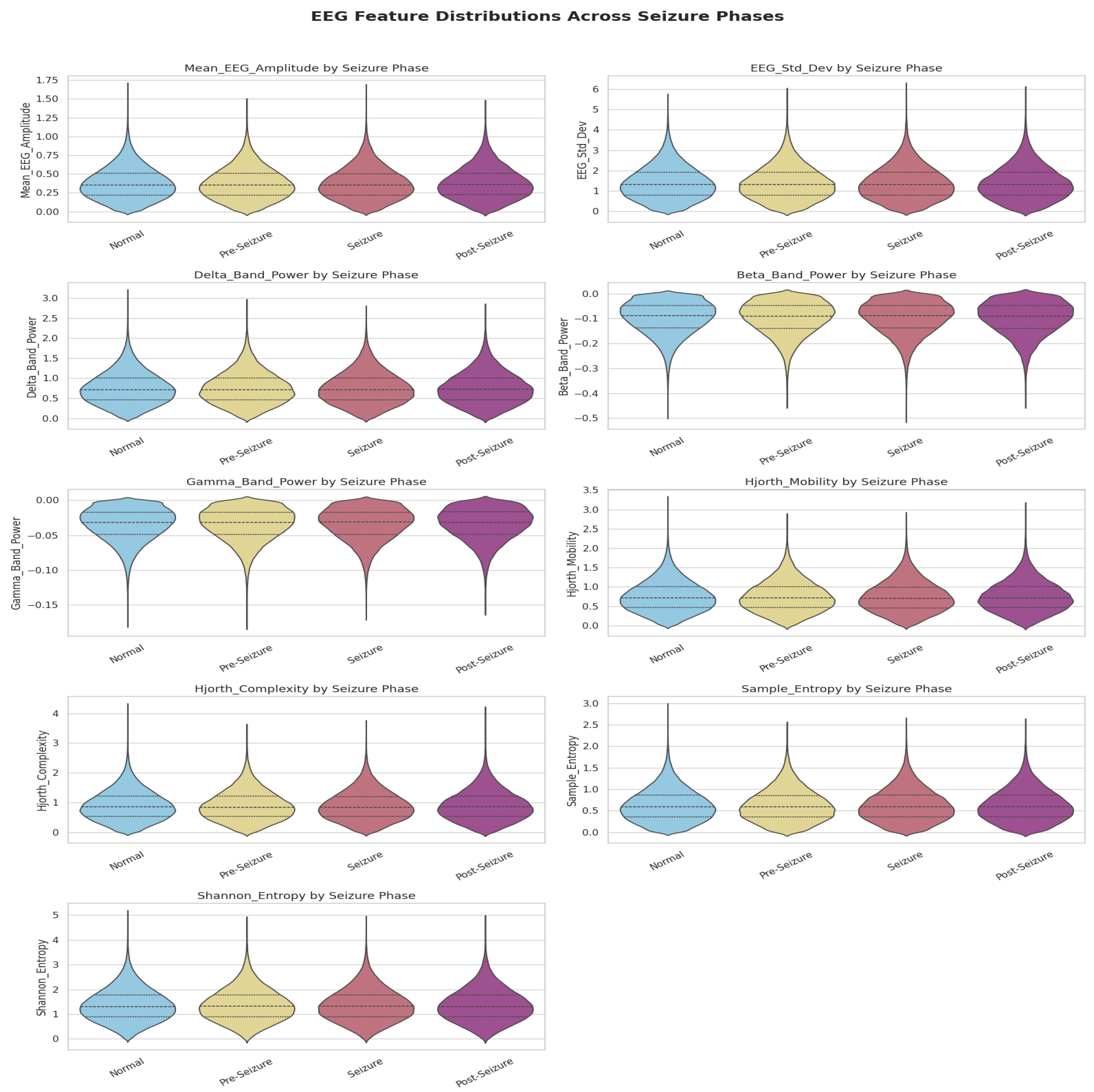

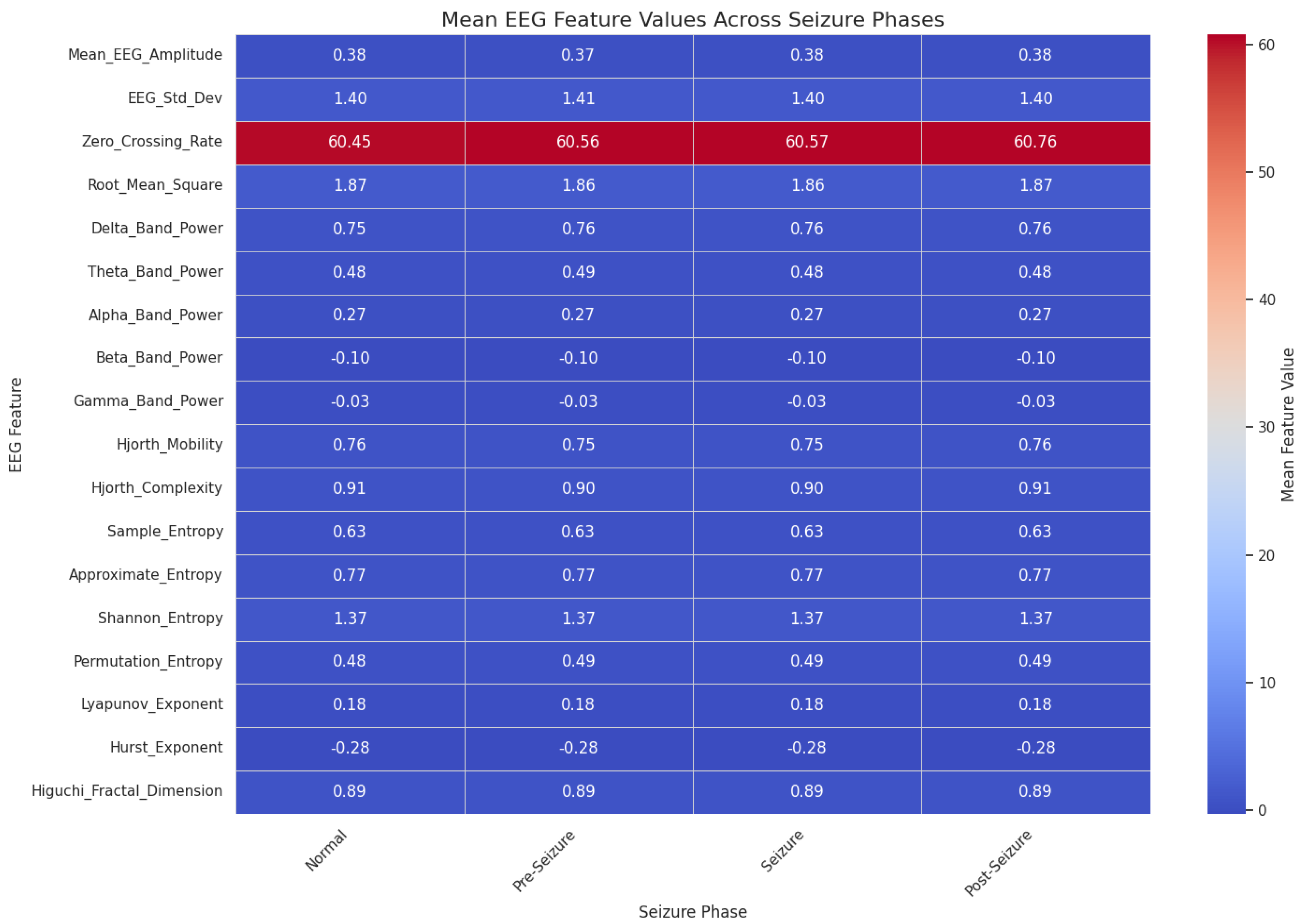

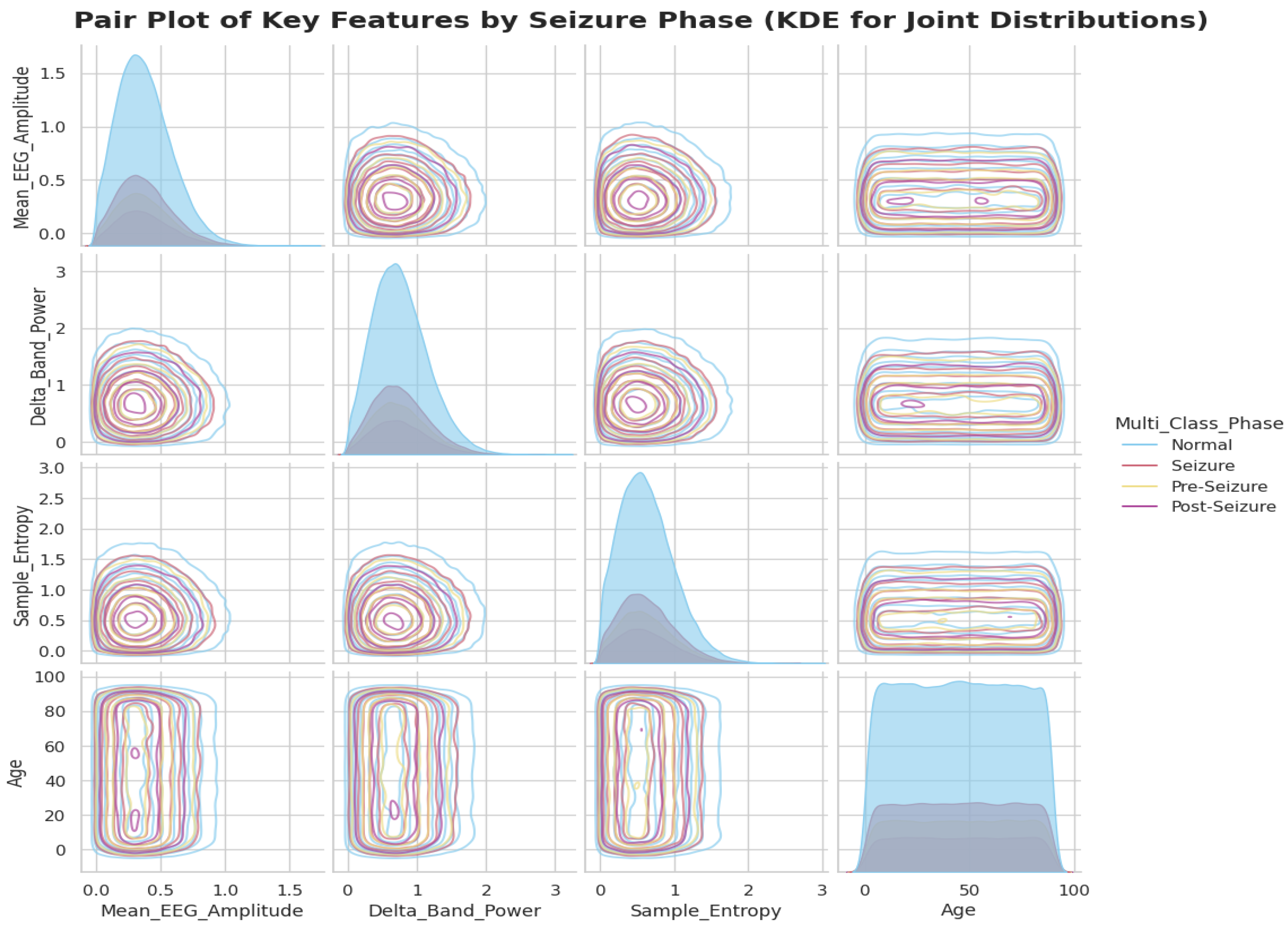

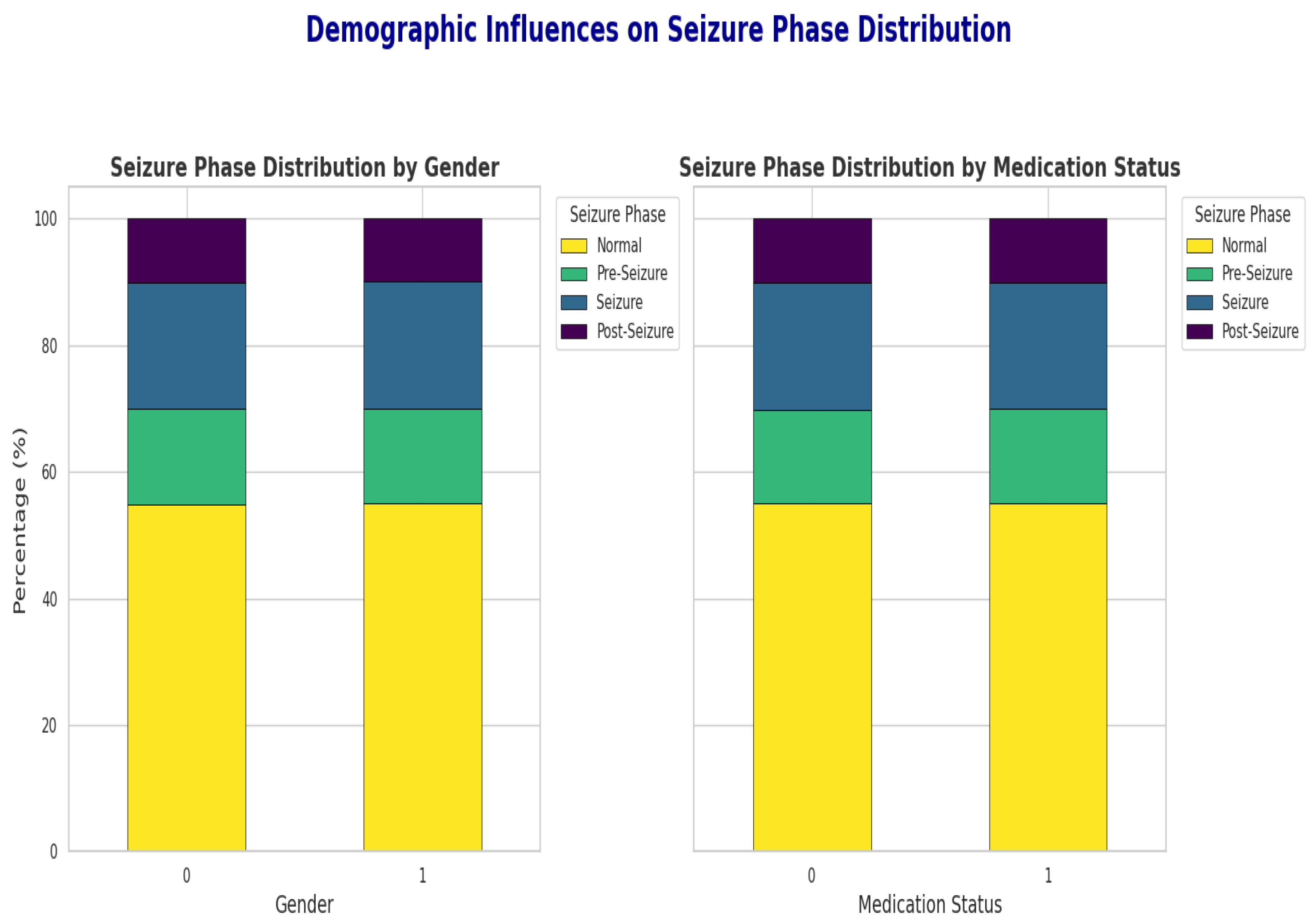

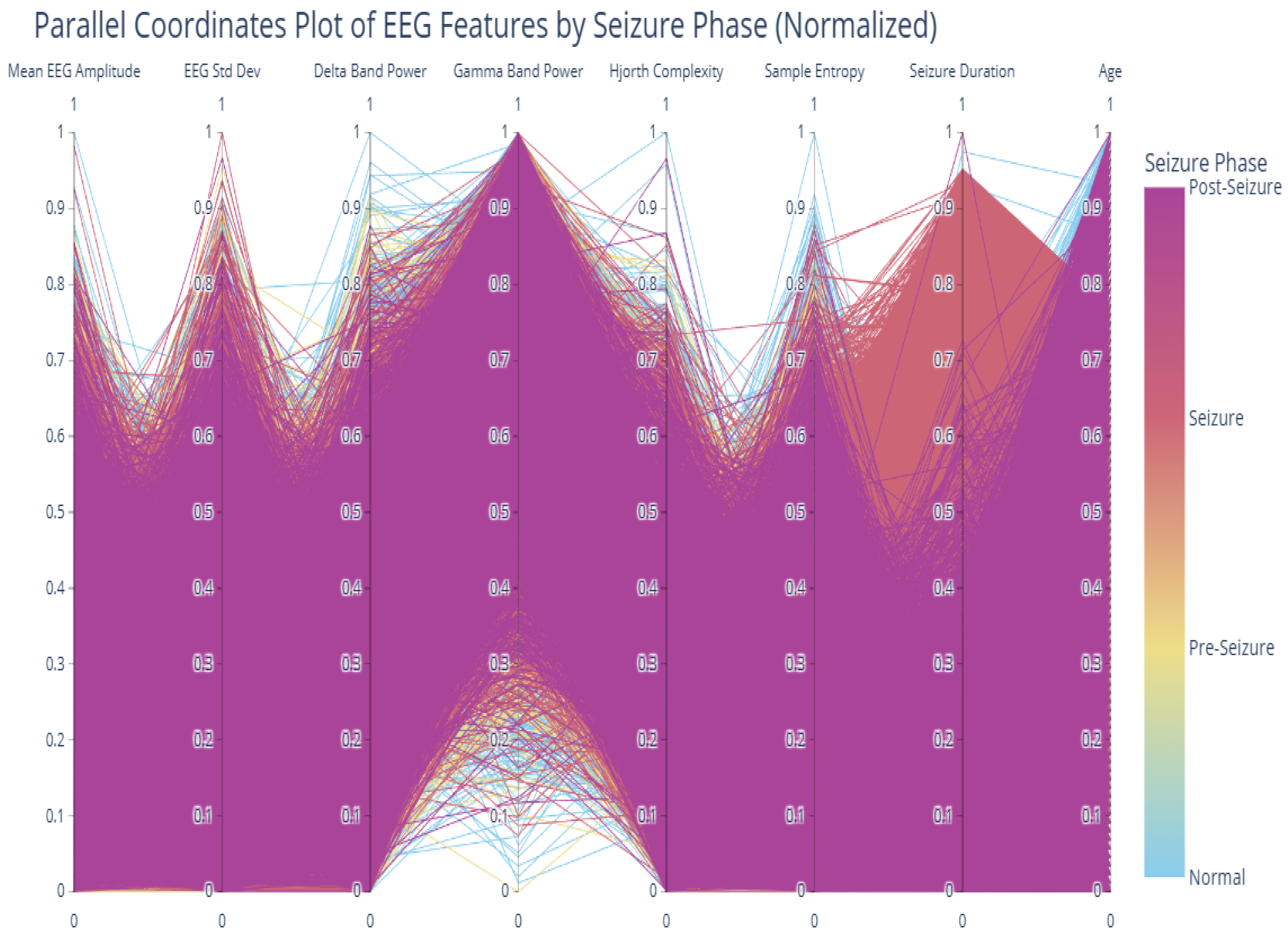

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Exploratory Analysis

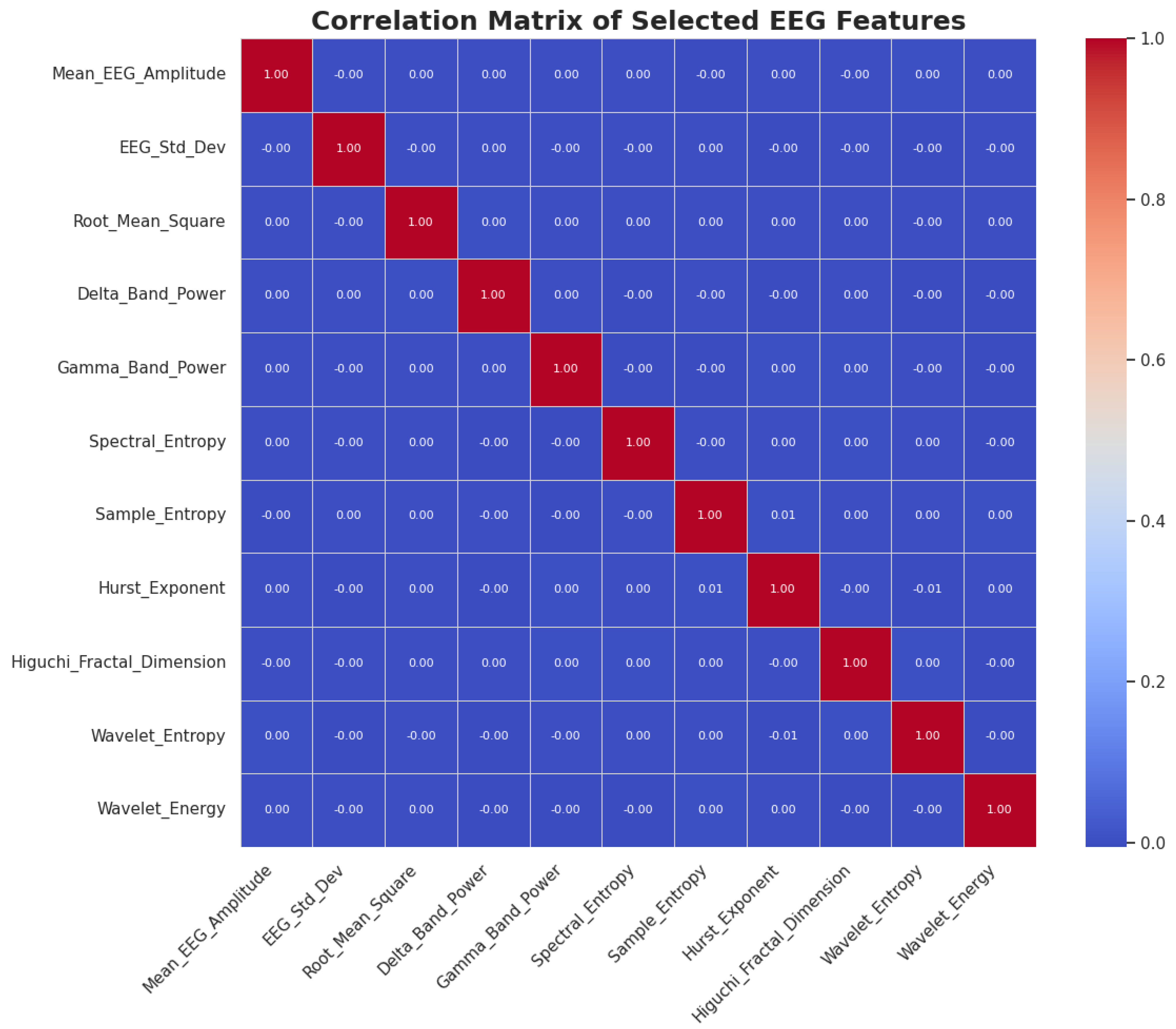

2.2.1. Feature Engineering

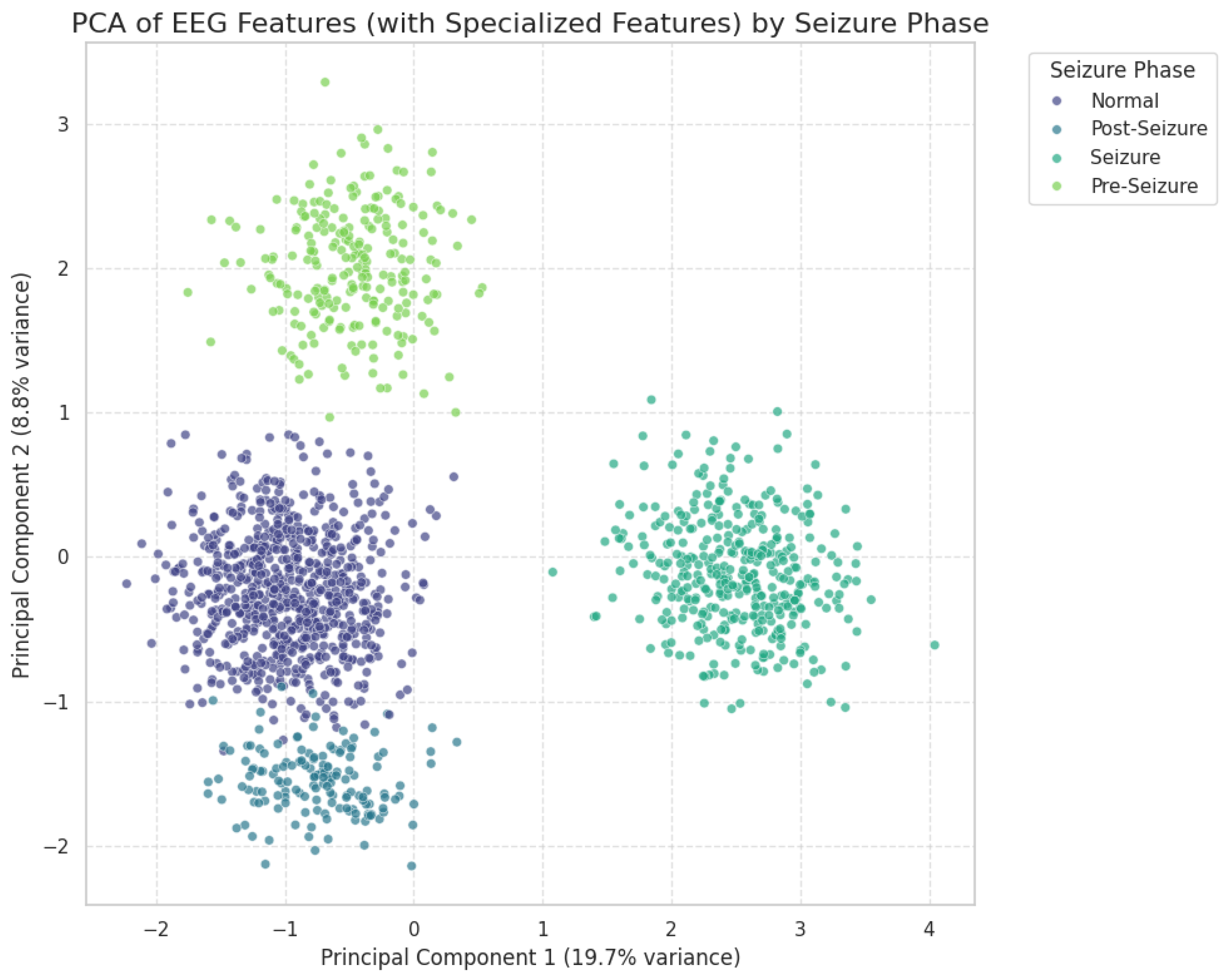

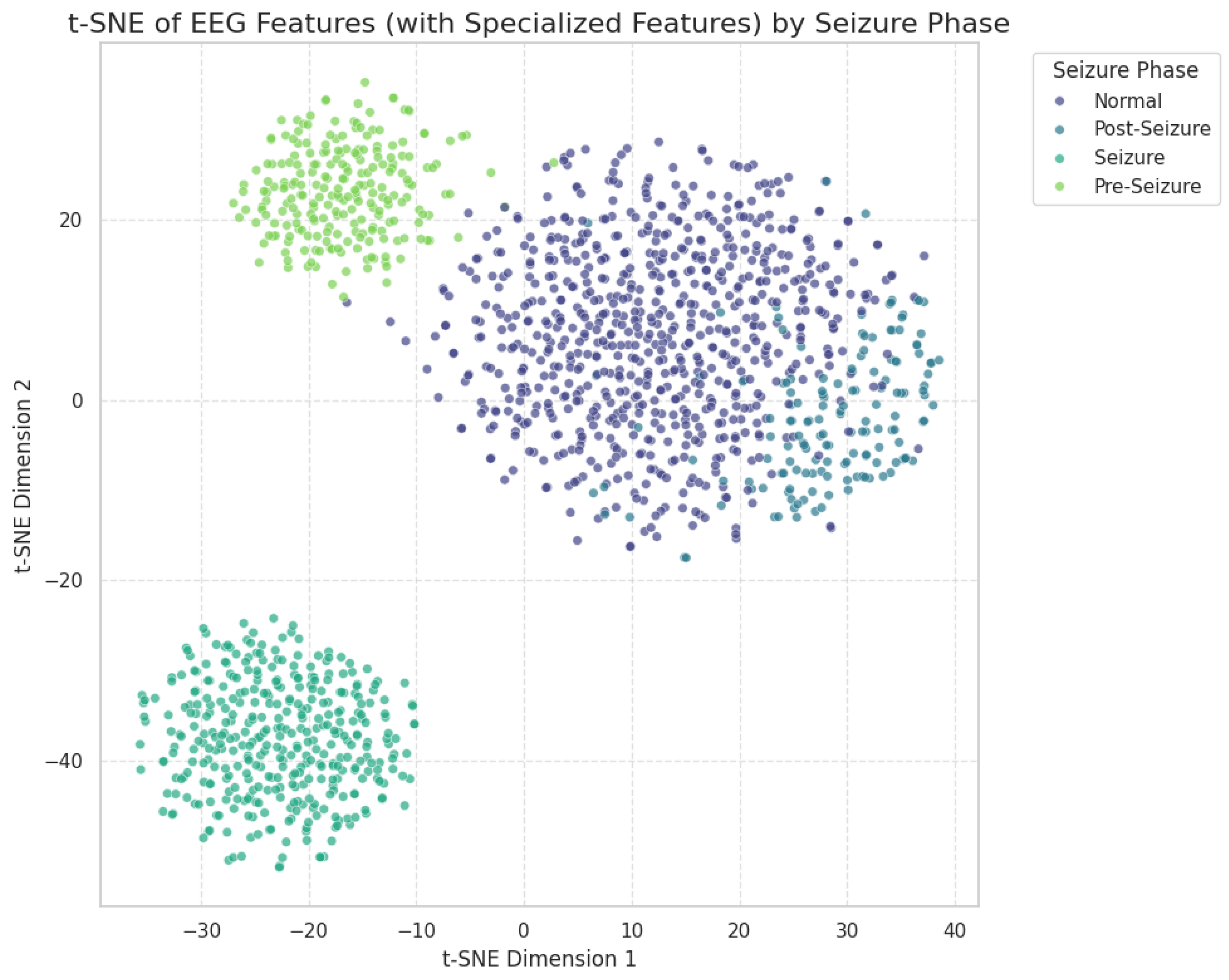

2.2.2. Dimensionality Reduction

2.3. Machine Learning Models

2.3.1. Random Forest

2.3.2. Support Vector Machine

2.3.3. K-Nearest Neighbors

2.3.4. Light Gradient Boosting Machine

2.3.5. Extreme Gradient Boosting

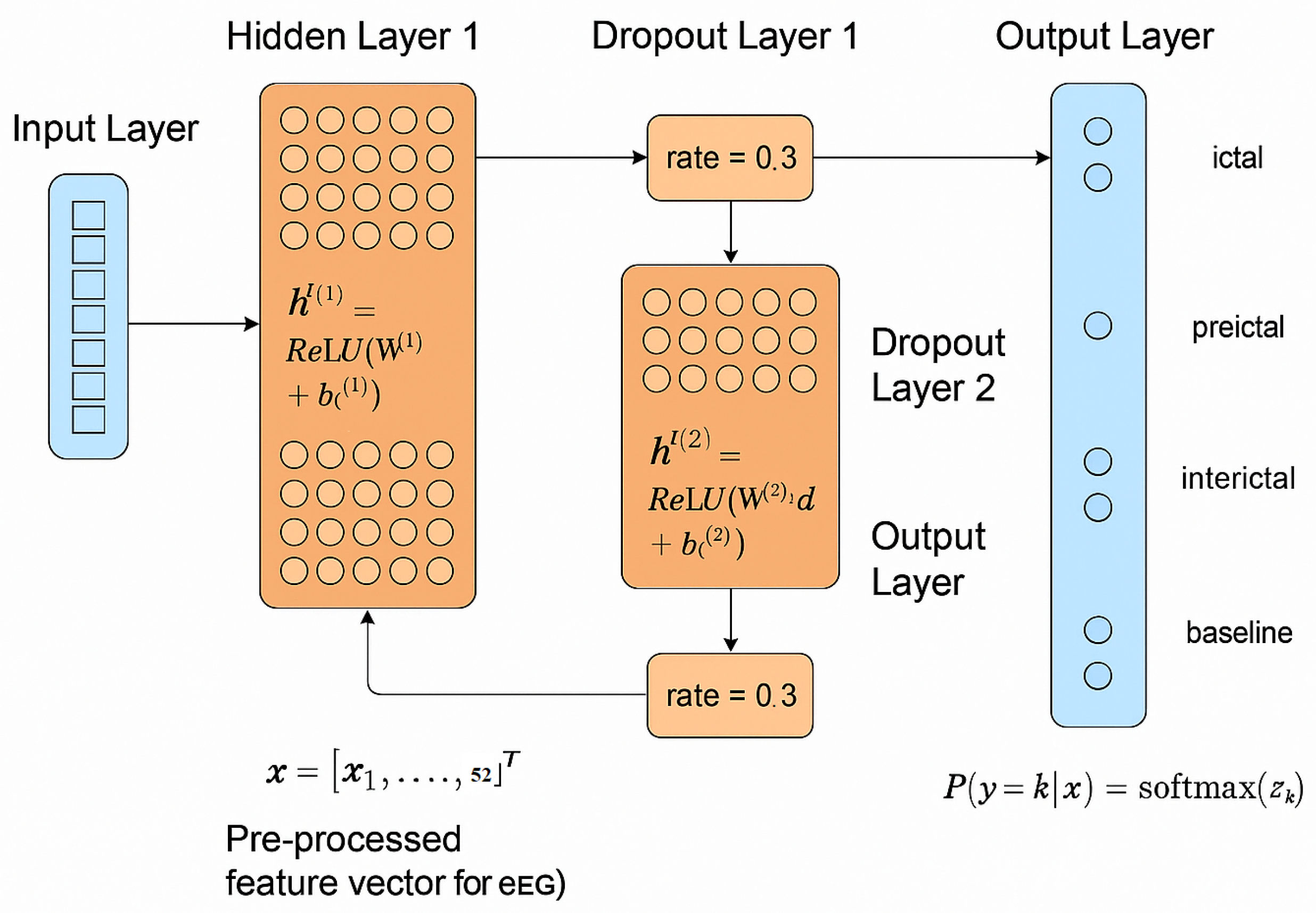

2.4. EpilepsyNet-XAI

- Input LayerThis layer receives the pre-processed feature vector for each EEG segment, where in Equation (21) represents the input feature vector with 52 EEG features.

- Hidden Layer 1A dense, fully connected layer transforms the input. For this layer, the output is computed as:where is the weight matrix (52 × 128), is the bias vector (128 × 1), and is the Rectified Linear Unit activation function defined in Equation (23).The hidden layer has 128 neurons, selected for computational efficiency and its ability to introduce non-linearity.

- Dropout Layer 1A dropout layer with a rate of 0.3 is applied after the first hidden layer to prevent overfitting by reducing complex co-adaptations between neurons. The output after dropout is computed as:where .

- Hidden Layer 2The second fully connected layer processes the output of the first dropout layer as:where is the weight matrix (128 × 64), and is the bias vector (64 × 1) for the second hidden layer, which has 64 neurons.

- Dropout Layer 2A second dropout layer with the same 0.3 dropout rate is applied for further regularization. The output is derived similarly to .

- Output LayerThe output layer is a dense layer with four neurons corresponding to the four EEG states (ictal, preictal, interictal, and baseline). A softmax activation function converts the output into a probability distribution, where the sum of probabilities across all classes equals one. For an input vector to the output layer, the probability for class k is computed as:

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

2.6. Explainable AI (XAI)

2.6.1. Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME)

2.6.2. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP)

2.7. Ablation and Robustness Analysis

2.7.1. Feature-Group Ablation

2.7.2. Class-Imbalance Robustness

2.7.3. Noise Perturbation Testing

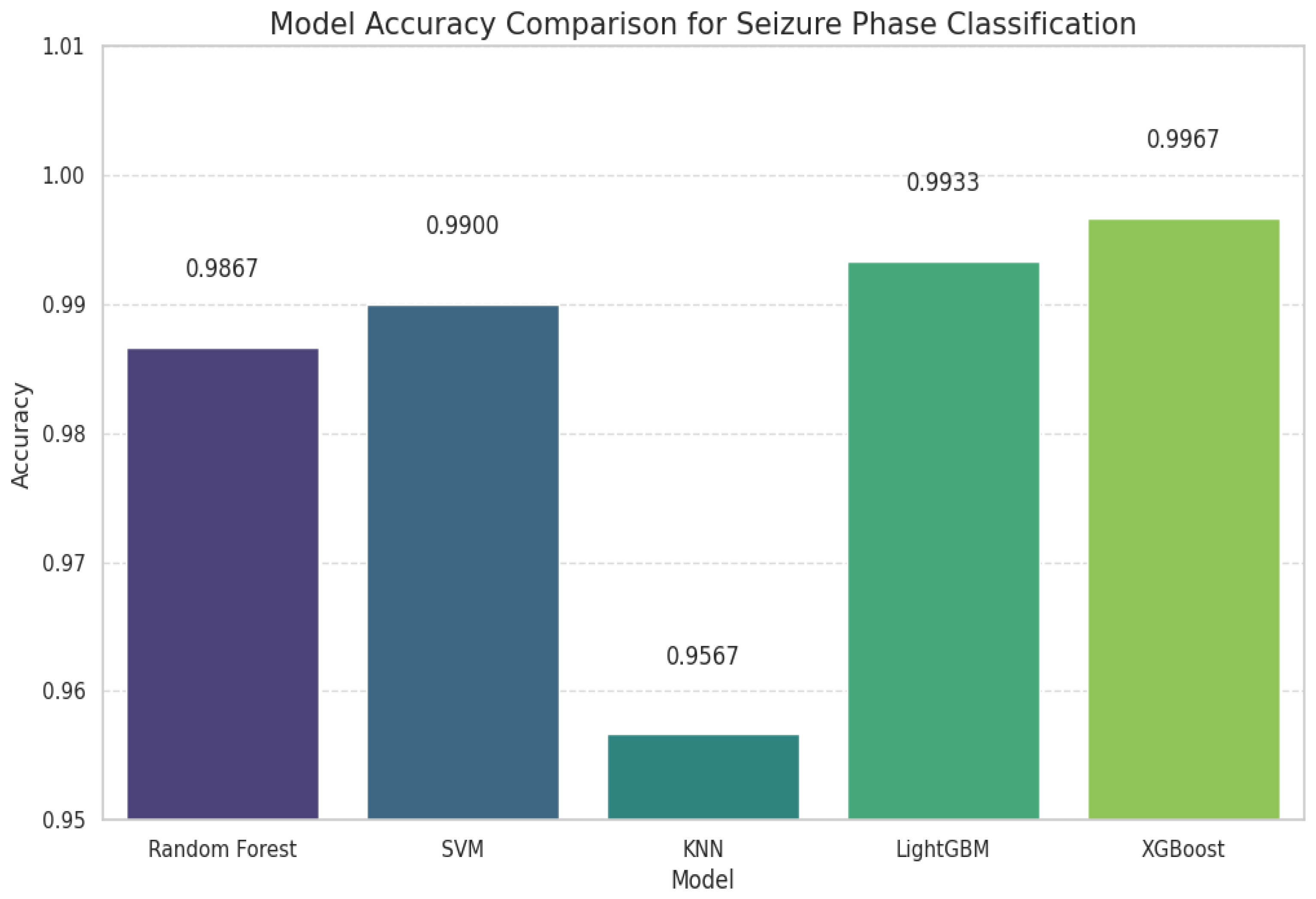

3. Results

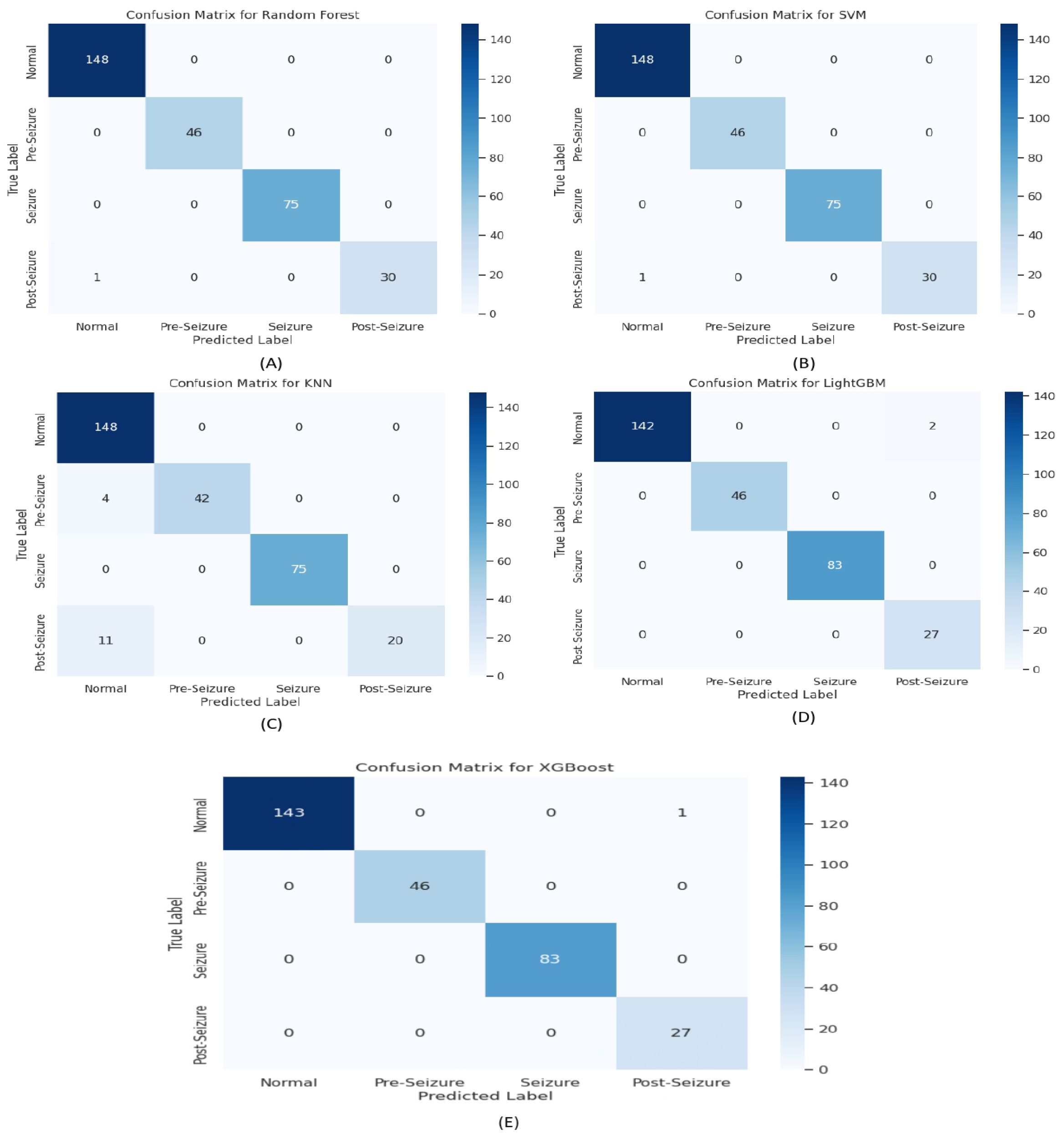

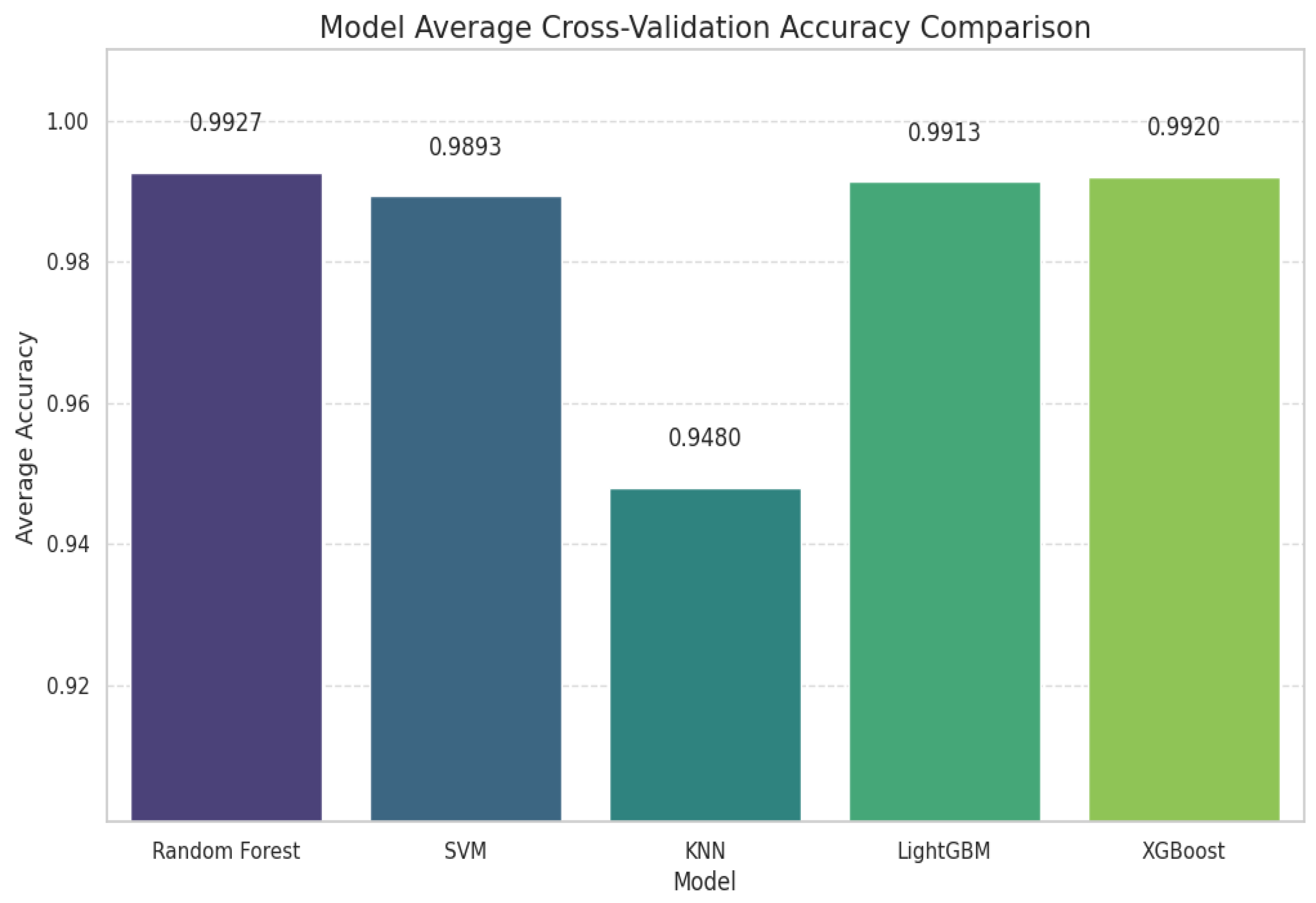

3.1. Cross-Validation and EpilepsyNet-XAI Performance

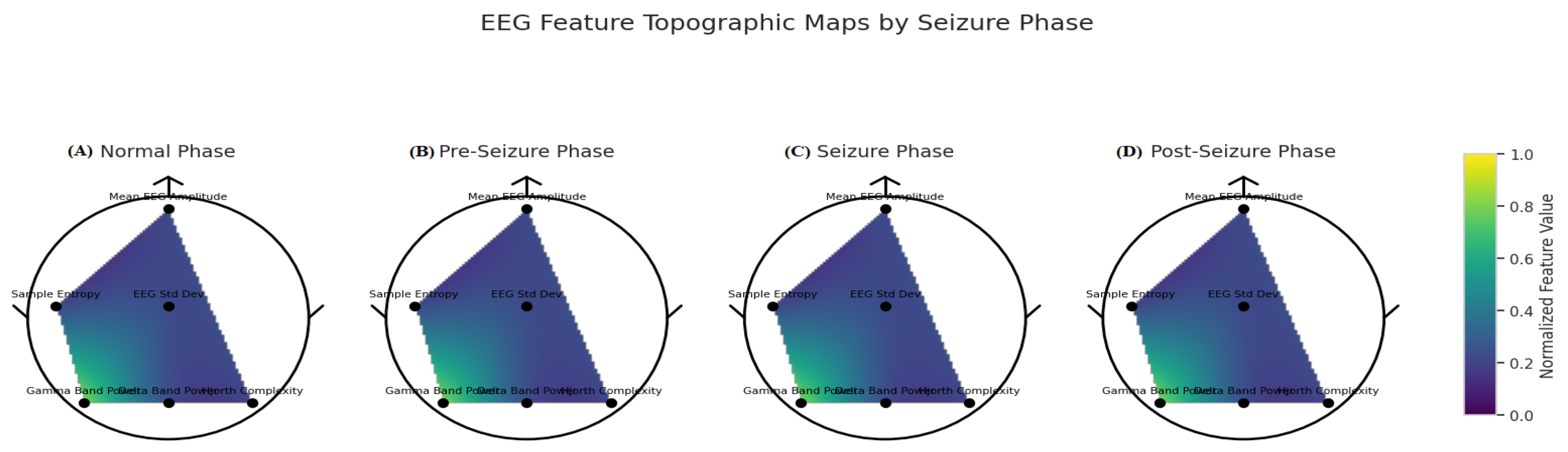

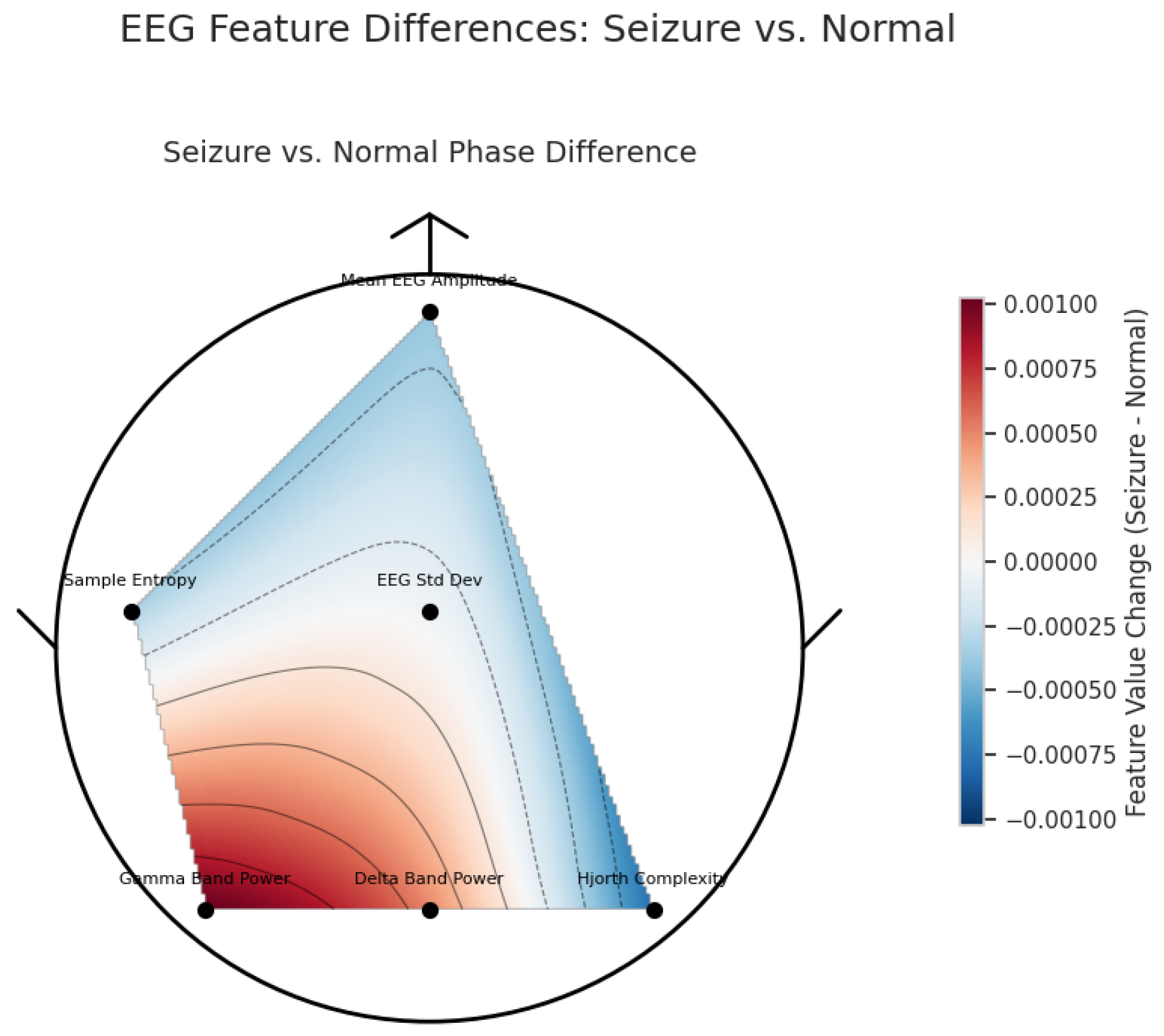

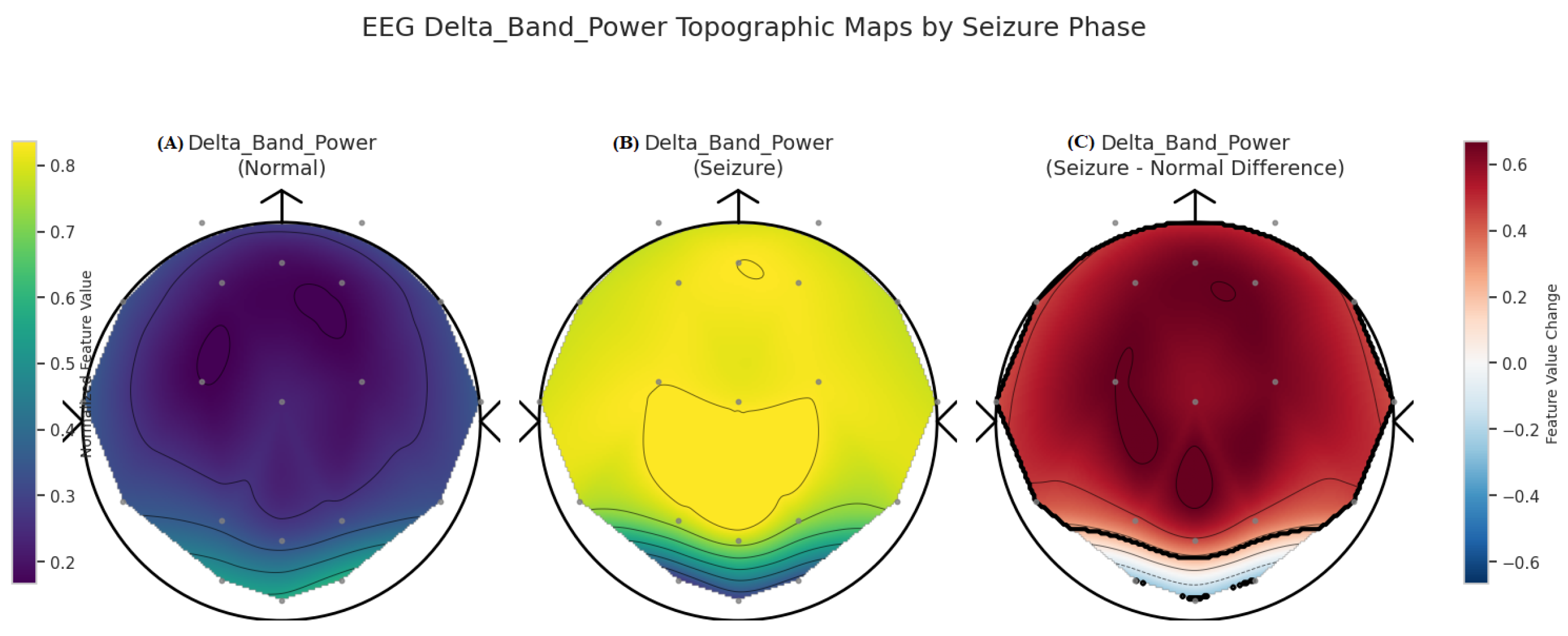

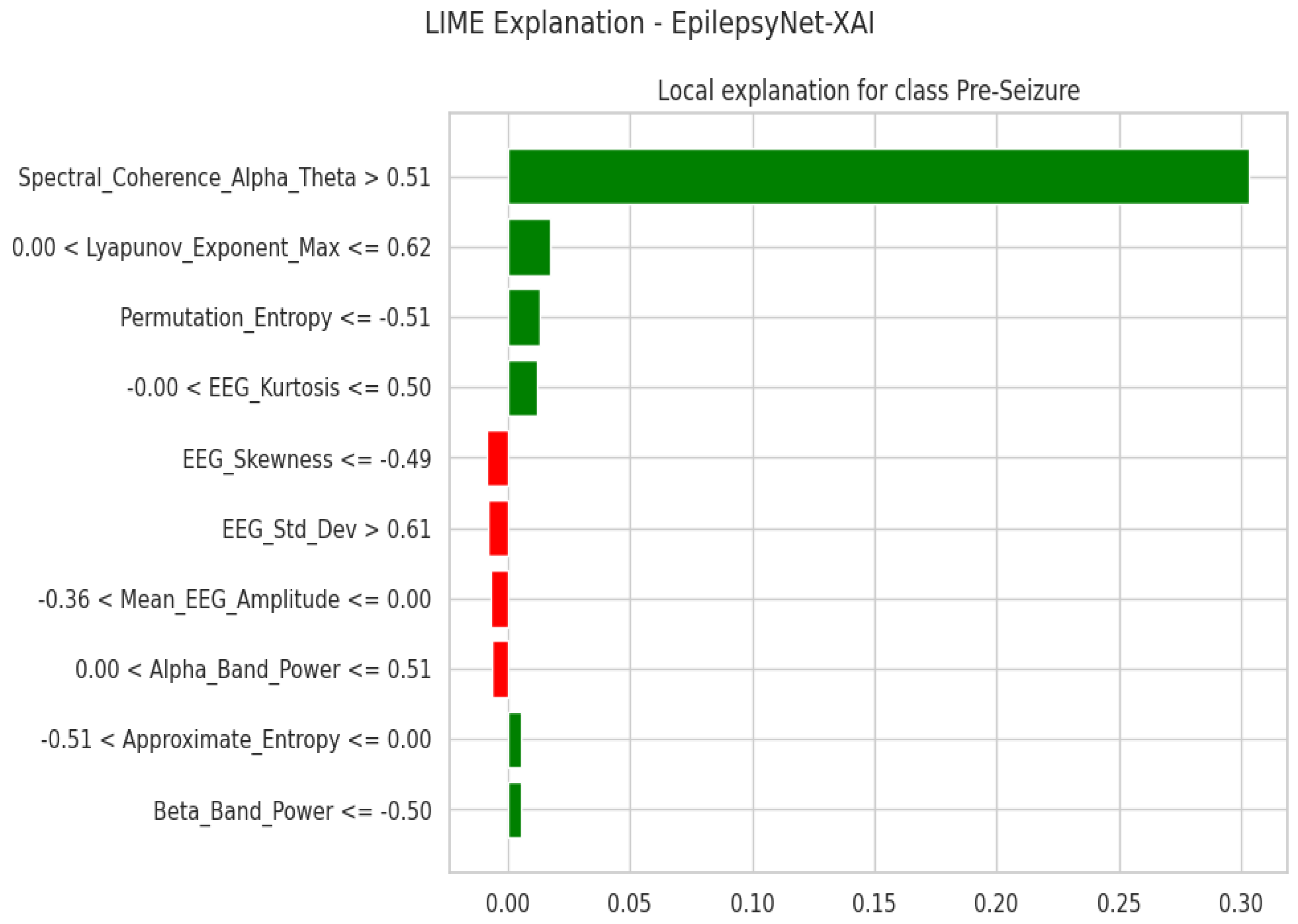

3.2. XAI Insights for EpilepsyNet

3.2.1. Local Explanation Using LIME

3.2.2. Feature Contributions for Normal Prediction Using SHAP Values

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giourou, E.; Stavropoulou-Deli, A.; Giannakopoulou, A.; Kostopoulos, G.K.; Koutroumanidis, M. Introduction to epilepsy and related brain disorders. In Cyberphysical Systems for Epilepsy and Related Brain Disorders: Multi-Parametric Monitoring and Analysis for Diagnosis and Optimal Disease Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, H.; Khan, Q.U.; Nadeem, N.; Pervaiz, I.; Ali, M.; Cheema, F.F. Epileptic seizures. Discoveries 2020, 8, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donahue, M.A.; Akram, H.; Brooks, J.D.; Modi, A.C.; Veach, J.; Kukla, A.; Benard, S.W.; Herman, S.T.; Farrell, K.; Ficker, D.M.; et al. Barriers to Medication Adherence in People Living With Epilepsy. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, e200403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, M.K.; Mahns, D.A.; Coorssen, J.R.; Shortland, P.J. Behavioural phenotypes in the cuprizone model of central nervous system demyelination. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, S.; Jung, Y.; Ko, D.S.; Kim, H.W.; Yoon, J.P.; Cho, S.; Song, T.J.; Kim, K.; Son, E.; et al. Exploring the Smoking-Epilepsy Nexus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies: Smoking and epilepsy. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J. EEG in the diagnosis, classification, and management of patients with epilepsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, ii2–ii7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedt-Aristizabal, D.; Fookes, C.; Dionisio, S.; Nguyen, K.; Cunha, J.P.S.; Sridharan, S. Automated analysis of seizure semiology and brain electrical activity in presurgery evaluation of epilepsy: A focused survey. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 1817–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saminu, S.; Xu, G.; Shuai, Z.; Abd El Kader, I.; Jabire, A.H.; Ahmed, Y.K.; Karaye, I.A.; Ahmad, I.S. A recent investigation on detection and classification of epileptic seizure techniques using EEG signal. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulate-Campos, A.; Coughlin, F.; Gaínza-Lein, M.; Fernández, I.S.; Pearl, P.; Loddenkemper, T. Automated seizure detection systems and their effectiveness for each type of seizure. Seizure 2016, 40, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, P.; Hussain, A.; Hignett, D.; Al-Jumeily, D.; Abdel-Aziz, K.; Hamdan, H. A machine learning system for automated whole-brain seizure detection. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2016, 12, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, L. Seizure Prediction: From Patient Perspectives to Advanced Signal Processing and Machine Learning Algorithms. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole Polytechnique, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, M. A Novel Non-EEG Wearable Device for the Detection of Epileptic Seizures. Ph.D. Thesis, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Escorcia-Gutierrez, J.; Beleno, K.; Jimenez-Cabas, J.; Elhoseny, M.; Alshehri, M.D.; Selim, M.M. An automated deep learning enabled brain signal classification for epileptic seizure detection on complex measurement systems. Measurement 2022, 196, 111226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, S.; Kumar, S.; Mohan, N.; Soman, K. EEG based automated detection of seizure using machine learning approach and traditional features. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 251, 123991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, F.; Mumtaz, N.; Mehmood, A. Next-Generation Tools for Patient Care and Rehabilitation: A Review of Modern Innovations. Actuators 2025, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, M.J.; Ko, H.J.; Jeong, O.R. XAI-based clinical decision support systems: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Jeong, O. Synergistic joint model of knowledge graph and llm for enhancing xai-based clinical decision support systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, A. EEG-based emotion classification using long short-term memory network with attention mechanism. Sensors 2020, 20, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldız, İ.; Garner, R.; Lai, M.; Duncan, D. Unsupervised seizure identification on EEG. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 215, 106604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Huang, W. Unsupervised EEG-based seizure anomaly detection with denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2024, 34, 2450047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, K.; Vishwanath, M.; Srinivasan, R.; Dutt, N.; Cao, H. Composing graphical models with generative adversarial networks for EEG signal modeling. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 1231–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, A.; Mehmood, F.; Kim, J. Towards Explainable Deep Learning in Computational Neuroscience: Visual and Clinical Applications. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, F.; Rehman, S.U.; Choi, A. Vision-AQ: Explainable Multi-Modal Deep Learning for Air Pollution Classification in Smart Cities. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Total Records | 289,010 EEG segments |

| Feature Groups (50 total)s | Time-Domain (15): Mean_EEG_Amplitude, Line_Length_Feature, Hjorth_Complexity, etc. Frequency-Domain (10): -Band Power, Beta-Band Power, Spectral Entropy, etc. Wavelet Features (5): Wavelet Entropy, DWT, CWT, Shannon Entropy, etc. Nonlinear Features (10): Sample Entropy, Lyapunov Exponent, Higuchi Fractal Dimension, etc. EEG-Derived Event Descriptors (6): Segment-level duration proxies, amplitude-based intensity indices, transient rate measures (e.g., spike-rate descriptors), etc. Metadata (4): Age, Gender, Medication Status, Seizure History |

| Target Labels | Segment Class Labels (Seizure State): 0 = Normal, 1 = Pre-Seizure, 2 = Seizure, 3 = Post-Seizure Seizure Type: 0 = Normal, 1 = Generalized, 2 = Focal |

| Demographics | Age: 1–90 years Gender: 0 = Female, 1 = Male Medication Status: 0 = No, 1 = Yes Seizure History: Count of prior seizures |

| Predicted: Class c | Predicted: Not Class c | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual: Class c | True Positive (TP) | False Negative (FN) |

| Actual: Not Class c | False Positive (FP) | True Negative (TN) |

| Model | Normal | Pre-Seizure | Seizure | Post-Seizure | Acc | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prec | Rec | F1 | Sup | Prec | Rec | F1 | Sup | Prec | Rec | F1 | Sup | Prec | Rec | F1 | Sup | ||

| SVM | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 144 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 46 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 83 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 27 | 0.9900 |

| KNN | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 144 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 46 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 83 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.85 | 27 | 0.9567 |

| LightGBM | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 144 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 46 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 83 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 27 | 0.9933 |

| XGBoost | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 144 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 46 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 83 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 27 | 0.9967 |

| RF | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 148 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 46 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 75 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 31 | 0.9867 |

| Model | Avg Accuracy | Avg Macro F1 | Avg Weighted F1 | Normal | Pre-Seizure | Seizure | Post-Seizure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.9907 | 0.9867 | 0.9906 | 0.9906 | 0.9934 | 1.0000 | 0.9628 |

| SVM | 0.9920 | 0.9884 | 0.9920 | 0.9919 | 0.9978 | 1.0000 | 0.9640 |

| KNN | 0.9587 | 0.9330 | 0.9559 | 0.9598 | 0.9798 | 1.0000 | 0.7924 |

| LightGBM | 0.9940 | 0.9916 | 0.9940 | 0.9940 | 0.9956 | 1.0000 | 0.9768 |

| XGBoost | 0.9927 | 0.9895 | 0.9926 | 0.9926 | 1.0000 | 0.9987 | 0.9668 |

| EpilepsyNet-XAI | 0.9950 | 0.9951 | 0.9970 | 0.9992 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9982 |

| Feature | Impact | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| FCI = −0.66 | +0.16 | Strongly supports ’Normal’; low connectivity corresponds to baseline state. |

| ACAT = −0.30 | +0.13 | Low – coherence typical in non-seizure conditions. |

| RR = −0.19 | +0.05 | Lower recurrence indicates less chaotic activity, typical of normal EEG. |

| SE = 1.22 | +0.04 | Moderate entropy suggests balanced, non-random signal behavior. |

| DBP = −0.73 | +0.04 | Low power aligns with wakeful resting states. |

| LEM = −0.09 | +0.03 | Lower chaos and higher signal regularity typical of non-seizure state. |

| Signal_Energy = −1.13 | +0.03 | Very low energy corresponds to calm brain activity. |

| _Band_Power = −0.26 | +0.02 | Low power is associated with normal resting state. |

| Zero_Crossing_Rate = 0.19 | +0.02 | Regular zero crossings indicate non-abnormal EEG. |

| _Band_Power = 0.44 | +0.02 | Presence of rhythm is common in normal resting states. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rehman, S.U.; Mehmood, F.; Kim, Y.-J.; Jung, H. EpilepsyNet-XAI: Towards High-Performance and Explainable Multi-Phase Seizure Analysis from EEG Features. Mathematics 2026, 14, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010125

Rehman SU, Mehmood F, Kim Y-J, Jung H. EpilepsyNet-XAI: Towards High-Performance and Explainable Multi-Phase Seizure Analysis from EEG Features. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010125

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehman, Sajid Ur, Faisal Mehmood, Young-Jin Kim, and Hachul Jung. 2026. "EpilepsyNet-XAI: Towards High-Performance and Explainable Multi-Phase Seizure Analysis from EEG Features" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010125

APA StyleRehman, S. U., Mehmood, F., Kim, Y.-J., & Jung, H. (2026). EpilepsyNet-XAI: Towards High-Performance and Explainable Multi-Phase Seizure Analysis from EEG Features. Mathematics, 14(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010125